Abstract

Superconductivity is due to an attractive interaction between electrons that, below a critical temperature, drives them to form Cooper pairs and to condense into a ground state separated by an energy gap from the unpaired states. In the simplest cases, the pairing is mediated by lattice vibrations and the wavefunction of the pairs is isotropic. Less conventional pairing mechanisms can favour more exotic symmetries of the Cooper pairs. Here, we report on point-contact spectroscopy measurements in PuCoGa5, a moderate heavy-fermion superconductor with a record high critical temperature Tc=18.5 K. The results prove that the wavefunction of the paired electrons has a d-wave symmetry, with four lobes and nodes, and show that the pairing is likely to be mediated by spin fluctuations. Electronic structure calculations, which take into account the full structure of the f-orbital multiplets of Pu, provide a hint of the possible origin of these fluctuations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A century on from the discovery of superconductivity, a complete understanding of some of the mechanisms that lead to its manifestation is still missing. Considerable research efforts are currently devoted to elucidating mechanisms by which pairs of electrons can bind together through the mediation of a boson field different than the one associated with the vibrations of a crystal lattice. PuCoGa5, a 5f-electron heavy-fermion superconductor with a record high critical temperature Tc=18.5 K1, is one of the many compounds for which the short-range, isotropic attraction provided by simple electron–phonon coupling does not appear as an adequate glue for electron pairing. Magnetic, or virtual valence, fluctuations may have an important role in the stabilization of the superconducting ground state in PuCoGa5, but the specific nature of the coupling mechanism remains obscure.

PuCoGa5 is a compound with unique properties. The Sommerfeld coefficient γ, as measured by specific-heat experiments, is between 77 and 95 mJ mol−1 K−1 (refs 1,2). The effective mass of electrons is about 1/5 of that measured for the isostructural unconventional superconductor CeCoIn52, suggesting a smaller degree of electronic correlation. The magnetic properties of PuCoGa5 and their possible relationship with the superconducting pairing have been debated, mainly because of conflicting results about the magnitude of the magnetic moment carried by the Pu ions. A Curie–Weiss susceptibility in the normal state was initially observed1, as expected for fluctuating local Pu3+ moments. Successive μSR studies showed no static, normal-state electronic magnetism3,4, and polarized neutron diffraction experiments showed a small and temperature-independent microscopic magnetization dominated by the orbital moment5.

The amplitude of the gap Δ (or at least of the gap ratio 2Δ/kBTc) has been estimated by different techniques. Using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to measure the Knight shift in the superconducting state of a sample with Tc=18.5 K, Curro et al.6 obtained 2Δ/kBTc=8 (Δ~6.3 meV).

Various band-structure calculations have been reported7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, showing that the details of the Fermi surface (FS) and the value of the local magnetic moment in PuCoGa5 depend on the approximations used to simplify the description of the electron correlations. In the local density/generalized-gradient approximations (LDA/GGA), the FS is quasi-two dimensional (2D)7,8,11,13, with at least two nearly cylindrical sheets, one hole-like around the Γ=(0, 0, 0) point of the reciprocal space (kx, ky, kz), and one electron-like around M=(π, π, 0). FSs with similar features have been observed in Fe-based superconductors15. Indeed, the coupling mechanism that seems to account for the high Tc superconductivity in iron pnictides (based on the nesting between hole and electron FS sheets through a vector associated with a peak in the spin susceptibility) had been proposed earlier for PuCoGa510. The FS remains qualitatively unchanged with the addition of the Coulomb-U interaction14.

Several experimental facts2,3,6,16,17,18,19 suggest that in PuCoGa5 the electrons in the Cooper pairs have a mutual angular momentum  =2, corresponding to a superconducting order parameter (OP) with d-wave symmetry, that is, the gap in the single-particle excitation spectrum has nodal lines intersecting the FS. A direct proof of the gap symmetry is, however, still missing. This is an important point, as the symmetry of the OP is closely related to the pairing mechanism. For instance, while isotropic electron–phonon attraction favors the formation of zero-angular-momentum pairs, with a spherically symmetric OP, d-wave symmetry is most easily realized if the pairing interaction is repulsive at short range and anisotropic at larger distances, as the one provided by effective spin–spin couplings on the border of antiferromagnetism20.

=2, corresponding to a superconducting order parameter (OP) with d-wave symmetry, that is, the gap in the single-particle excitation spectrum has nodal lines intersecting the FS. A direct proof of the gap symmetry is, however, still missing. This is an important point, as the symmetry of the OP is closely related to the pairing mechanism. For instance, while isotropic electron–phonon attraction favors the formation of zero-angular-momentum pairs, with a spherically symmetric OP, d-wave symmetry is most easily realized if the pairing interaction is repulsive at short range and anisotropic at larger distances, as the one provided by effective spin–spin couplings on the border of antiferromagnetism20.

A magnetic nature of the Cooper pairing mediator in PuCoGa5 has been discussed by several authors (a recent review can be found in ref. 21). Flint et al.22 considered virtual valence fluctuations of the magnetic Pu configurations, creating Kondo screening channels with different symmetry, and demonstrated that in a lattice of magnetic ions, exchanging spin with conduction electrons in two different channels, a condensate of composite pairs between local moments and electrons is formed. These models must be reconciled with the temperature-independent susceptibility observed in the normal state5. A phononic mechanism in the framework of the d-wave Eliashberg theory has been discussed in ref. 19. Although able to reproduce a number of experimental observations, this model requires an electron–phonon (e–ph) coupling constant λ that is much higher than the value experimentally deduced from the time relaxation of photoinduced quasiparticles23 (λ=0.20–0.26).

To determine the amplitude and the symmetry of the superconducting OP, and thus get some insight into the possible coupling mechanism, we performed point-contact Andreev-reflection spectroscopy (PCARS) measurements in PuCoGa5 single crystals. PCARS has very often been the key experimental tool to elucidate the unconventional nature of superconductivity in very different materials, from heavy fermions24 to iron-based superconductors25.

Based on these PCARS measurements, we prove that the OP of PuCoGa5 has a d-wave symmetry, consistent with indirect indications from NMR and μSR measurements. In freshly annealed crystals of 239PuCoGa5 with bulk  , the analysis of different PCAR spectra gives a gap amplitude at T→0 equal to Δ=5.1±0.3 meV, corresponding to a gap ratio 2Δ/kBTc=6.4±0.4, that indicates a strong electron–boson coupling. A similar gap ratio is obtained in 242PuCoGa5 with Sb impurities and a reduced Tc=14.5 K. In both cases, the temperature dependence of the gap is consistent with the predictions of the Eliashberg theory for strong-coupling superconductivity if spin fluctuations provide the mediating bosons. A characteristic boson energy Ω0=5.3–8.0 meV (within the range of spin-fluctuation energies determined by NMR) and a coupling constant λ=2.2–3.7 allow reproducing the low-temperature gap values. These results show that PuCoGa5 is an unconventional, strong-coupling d-wave superconductor and indicate spin fluctuations as the probable boson that mediates the electron pairing. Furthermore, we demonstrate that this picture is not in contradiction with the temperature-independent magnetization. Indeed, electronic structure calculations accounting for the full structure of the 5f-orbital atomic multiplets and their hybridization with the conduction bands show that the Pu atoms carry non-vanishing average moments as their f shells fluctuate between a singlet and a sextet configuration. These fluctuations are dynamically compensated by fluctuations in the surrounding cloud of conduction electrons such that the compound as a whole remains non-magnetic.

, the analysis of different PCAR spectra gives a gap amplitude at T→0 equal to Δ=5.1±0.3 meV, corresponding to a gap ratio 2Δ/kBTc=6.4±0.4, that indicates a strong electron–boson coupling. A similar gap ratio is obtained in 242PuCoGa5 with Sb impurities and a reduced Tc=14.5 K. In both cases, the temperature dependence of the gap is consistent with the predictions of the Eliashberg theory for strong-coupling superconductivity if spin fluctuations provide the mediating bosons. A characteristic boson energy Ω0=5.3–8.0 meV (within the range of spin-fluctuation energies determined by NMR) and a coupling constant λ=2.2–3.7 allow reproducing the low-temperature gap values. These results show that PuCoGa5 is an unconventional, strong-coupling d-wave superconductor and indicate spin fluctuations as the probable boson that mediates the electron pairing. Furthermore, we demonstrate that this picture is not in contradiction with the temperature-independent magnetization. Indeed, electronic structure calculations accounting for the full structure of the 5f-orbital atomic multiplets and their hybridization with the conduction bands show that the Pu atoms carry non-vanishing average moments as their f shells fluctuate between a singlet and a sextet configuration. These fluctuations are dynamically compensated by fluctuations in the surrounding cloud of conduction electrons such that the compound as a whole remains non-magnetic.

Results

Point-contact Andreev-reflection measurements

Figure 1 presents the temperature dependence of the raw conductance curves of a point contact whose normal-state resistance is 6.2 Ω. All the curves but the lowest-temperature one are shifted downward for clarity. The top curve is measured at T=1.8 K, which means about Tc/10. This ensures that the gap extracted from it is representative of the gap for T→0. The high-energy tails of the conductance curves are temperature independent, as shown in the inset, where the curves measured at T=1.8 K and in the normal state are reported without vertical offset as an example. This demonstrates that the contact is in the perfectly ballistic regime, with no contribution due to Maxwell terms in the contact resistance, that is, there is no diffusion in the contact region and the maximum excess energy with which the electrons are injected into the superconductor is exactly eV. Meeting this condition is essential for energy-resolved spectroscopy to be possible. The absence of heating effects in the contact is also witnessed by the coincidence between the Andreev critical temperature  (that is, the temperature at which the Andreev signal disappears and the normal-state conductance is recovered, here between 18.0 K and 18.5 K) and the bulk Tc=18.1 K determined from resistivity measurements (as shown in Supplementary Fig. S1).

(that is, the temperature at which the Andreev signal disappears and the normal-state conductance is recovered, here between 18.0 K and 18.5 K) and the bulk Tc=18.1 K determined from resistivity measurements (as shown in Supplementary Fig. S1).

Experimental raw conductance curves of a Au/PuCoGa5 point contact with RN=6.2 Ω measured at different temperatures. All the curves apart from the top one are vertically shifted for clarity. The inset shows the curve at 1.8 K and the curve at 20.02 K (and thus in the normal state) without any shift. The superposition of the tails is one of the indicators that the contact is in the ballistic regime.

It is worth noticing that the normal-state conductance curves in PuCoGa5 do not show the strong asymmetry observed in various heavy-fermion compounds like, for instance, CeCoIn526, UBe1327 and URu2Si228,29 (but not, for example, in UPt330). In some cases, this asymmetry was ascribed to magnetic properties of the normal state. In CeCoIn5, the asymmetry appears below the temperature where a coherent heavy-fermion liquid develops26, and has been explained in terms of a Fano resonance involving localized states near the interface and itinerant heavy electrons in the bulk31. The absence of a strong, temperature-dependent asymmetry in PuCoGa5 may thus confirm that superconductivity in this compound develops out of an incoherent metallic state32.

In order to compare the experimental curves to the theoretical ones, a normalization is required, that is, a division by the conductance of the same point contact when the superconductor is in the normal state. Owing to the extremely high value of the upper critical field in PuCoGa5, this cannot be achieved by applying a magnetic field to suppress superconductivity at low temperature. However, owing to the moderate Tc and the negligible temperature dependence of the normal-state conductance (witnessed by the absence of any change in shape of the tails of the conductance curves at |eV|>15 meV), we can safely normalize the conductance curves at any  by the normal-state conductance curve measured at (or just above)

by the normal-state conductance curve measured at (or just above)  .

.

The result of this normalization is shown in Fig. 2 (symbols) for two contacts made on different places of freshly broken surfaces of the same sample. The two contacts have the same  but different normal-state resistance RN. It is worth noticing that the Andreev signal is very high, while in most heavy-fermion compounds it is suppressed to a few percent of the normal-state conductance24,31. This effect has been ascribed to extrinsic causes (for example, elastic scattering in the contact region) or intrinsic ones (for example, an energy-dependent quasiparticle lifetime or the existence of unpaired light electrons below Tc that do not participate in Andreev reflection31). None of these effects seem to have a role in our point contacts.

but different normal-state resistance RN. It is worth noticing that the Andreev signal is very high, while in most heavy-fermion compounds it is suppressed to a few percent of the normal-state conductance24,31. This effect has been ascribed to extrinsic causes (for example, elastic scattering in the contact region) or intrinsic ones (for example, an energy-dependent quasiparticle lifetime or the existence of unpaired light electrons below Tc that do not participate in Andreev reflection31). None of these effects seem to have a role in our point contacts.

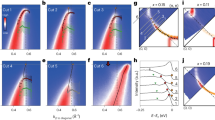

(a) The conductance curve (measured at 1.8 K) of a Au/PuCoGa5 point contact with normal-state resistance RN=6.2 Ω after normalization (symbols) and the relevant 2D-BTK fit assuming a d-wave gap (line). The parameters of the fitting function are as follows: the gap Δ at T=0 K, the spectral broadening parameter Γ, the measure of the barrier strength at the interface Z and the angle α between the direction of current injection and the direction along which the gap is maximum (that is, it has a lobe). Their values for this curve are Δ=4.85 meV, Γ=0.6 meV, Z=0.84 and α=π/4. The corresponding direction of current injection is shown in the inset. (b) Same as in (a), but for a contact with normal-state resistance RN=5.5 Ω. The best-fitting parameters are Δ=5.10 meV, Γ=0.8 meV, Z=0.7 and α=π/9.25. The different shape of the two curves in (a) and (b) simply arises from the different direction of the current injected with respect to the lobes of the d-wave symmetry (insets).

The curve in Fig. 2a is similar to the best ones observed in cuprates33,34,35,36. Its shape, with a very clear zero-bias conductance peak (ZBCP), whose amplitude is greater than 2, is incompatible with a isotropic OP (Fig. 3a, top). This is clear in Fig. 3b that reports theoretical curves calculated within the 2D Blonder–Tinkham–Klapwijk (2D-BTK) model for Andreev reflection37,38,39,40 at a normal metal/isotropic superconductor contact for different values of the dimensionless barrier parameter Z. All the curves present either a plateau or two maxima symmetric about zero bias, and their amplitude is always <2 even in ideal conditions (T=0, absence of broadening effects). Instead, the experimental curve in Fig. 2a looks very similar to those calculated within the same 2D-BTK model in the case of a nodal OP with a change of sign at the FS. In particular, theoretical curves closely resembling the measured one can be obtained if the OP has a d-wave symmetry (shown in Fig. 3a, bottom), the current is mainly injected along the nodal direction (that is, at an angle α=π/4 with respect to the lobes of the d-wave gap38,39) and  , as shown in Fig. 3c. In these conditions, the central peak is ascribed to zero-energy Andreev bound states, arising from the constructive interference between electron-like and hole-like quasiparticles that feel OPs with different signs38,39.

, as shown in Fig. 3c. In these conditions, the central peak is ascribed to zero-energy Andreev bound states, arising from the constructive interference between electron-like and hole-like quasiparticles that feel OPs with different signs38,39.

(a) Plot of the OP in spherical coordinates in the reciprocal space. The cases of an s-wave (top) and of a  -wave (bottom) OP are shown. (b) Theoretical normalized conductance curves calculated within the 2D-BTK model at T=0 and γ=0 for a normal metal/s-wave superconductor interface with different values of the dimensionless barrier strength Z. From top to bottom, Z=0, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 1.0 and 2.0. (c,d) Normalized conductance curves at T=0 K calculated with the 2D-BTK model for a normal metal/d-wave superconductor interface with the same Z values as in (b) and assuming α=π/4 and α=π/8, respectively; α is the angle between the direction of the injected current and the kx axis.

-wave (bottom) OP are shown. (b) Theoretical normalized conductance curves calculated within the 2D-BTK model at T=0 and γ=0 for a normal metal/s-wave superconductor interface with different values of the dimensionless barrier strength Z. From top to bottom, Z=0, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 1.0 and 2.0. (c,d) Normalized conductance curves at T=0 K calculated with the 2D-BTK model for a normal metal/d-wave superconductor interface with the same Z values as in (b) and assuming α=π/4 and α=π/8, respectively; α is the angle between the direction of the injected current and the kx axis.

The shape of the conductance curve in Fig. 2b is very different, but can be readily explained within the same scenario of d-wave superconductivity if the current is injected along a different direction38,39. Indeed, this curve looks similar to the theoretical Andreev-reflection spectra calculated within the 2D-BTK model for Z=0.5–0.7 and α=π/8 and shown in Fig. 3d.

Fit of the experimental curves

Solid lines in Fig. 2a,b are the results of a quantitative fit of the experimental spectra by using the aforementioned 2D-BTK model. The parameters of the model are Δ (here intended as the maximum amplitude of the gap), the barrier strength Z, the angle α and a spectral broadening parameter Γ that must usually be included in the model when fitting experimental curves40. Here  so that it does not add any ambiguity to the determination of the gap amplitude. The finite experimental temperature (1.8 K) has been taken into account. The best-fitting values of the parameters for the curves of Fig. 2a,b are indicated in the legend. The values of the gap (4.85 meV and 5.10 meV, respectively) are very similar and this is certainly the most important result, but also the barrier and broadening parameters are very similar. The only relevant difference, as expected, is in the value of the angle α, as shown pictorially in the insets of Fig. 2.

so that it does not add any ambiguity to the determination of the gap amplitude. The finite experimental temperature (1.8 K) has been taken into account. The best-fitting values of the parameters for the curves of Fig. 2a,b are indicated in the legend. The values of the gap (4.85 meV and 5.10 meV, respectively) are very similar and this is certainly the most important result, but also the barrier and broadening parameters are very similar. The only relevant difference, as expected, is in the value of the angle α, as shown pictorially in the insets of Fig. 2.

Figure 4a shows an example of how the normalized conductance curves evolve with increasing temperature. The experimental data (symbols) are compared with the 2D-BTK fit (solid lines). The fit is good at all temperatures; note that both Z and α are independent of temperature and were thus kept constant for all the curves. We also kept Γ nearly constant so that the only parameter that varies significantly with temperature is the gap amplitude Δ.

(a)Temperature dependence of the normalized conductance curves of a contact with RN=6.2 Ω (symbols) and their fit with the 2D-BTK model (lines). The curves are vertically offset for clarity. (b) Temperature dependence of the gap extracted from the fit of the conductance curves of three different contacts (symbols). The solid line is the Δ(T) function calculated within the Eliashberg theory by assuming a spin-fluctuation-like spectrum peaked at Ω0=6.5 meV and a coupling constant λ=2.37.

The temperature dependence of the gap as obtained from the fit of three different sets of conductance curves (in three different contacts) is shown in Fig. 4b. It is clear that the gap values are reproducible to a high degree; at low temperature, they range between 4.85 and 5.30 meV. The vertical spread of gap values can be used to evaluate a posteriori the uncertainty on the gap itself; this is obviously much greater than the uncertainty arising from the fit of a single curve, which can be empirically determined as the range of gap values that allow an acceptable (that is, within some confidence limit) fit of the conductance curve, when all the other parameters are varied as well. To be conservative, we can assume the experimental gap at low temperature to be equal to Δ=5.1±0.3 meV, corresponding to a gap ratio 2Δ/kBTc=6.4±0.4, much larger than the value of 4.28 expected in weak-coupling d-wave superconductors according to the Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) theory. The spread of gap values is small at low temperature and maximizes at around 14 K. Although the general trend of the gap seems to be compatible with a BCS-like Δ(T) dependence (but of course, with a non-BCS gap ratio), this uncertainty does not favour discussing it in detail.

Analysis of the data within Eliashberg theory

The solid line in Fig. 4b, which is in fairly good agreement with the experimental data, represents the theoretical temperature dependence of the gap calculated within the strong-coupling theory for superconductivity (known as the Eliashberg theory41,42) by assuming mediating bosons with a spin-fluctuation-like spectrum43:  where Ω0 is the energy of the peak and Ωmax is a cutoff energy that we chose equal to 4Ω044. The shape of the spectrum is shown in the inset of Fig. 5a. In addition to the peak energy Ω0, the minimal Eliashberg model contains two other parameters that can be adjusted to reproduce the experimental Tc and low-temperature gap: the electron–boson coupling constant λ and the Coulomb pseudopotential μ* (that describes the effects of the Coulomb repulsion and normally ranges between 0 and 0.242). The concentration of defects in the material was also taken into account by using a scattering parameter γd=0.25 meV obtained by fitting the temperature dependence of the local spin susceptibility6.

where Ω0 is the energy of the peak and Ωmax is a cutoff energy that we chose equal to 4Ω044. The shape of the spectrum is shown in the inset of Fig. 5a. In addition to the peak energy Ω0, the minimal Eliashberg model contains two other parameters that can be adjusted to reproduce the experimental Tc and low-temperature gap: the electron–boson coupling constant λ and the Coulomb pseudopotential μ* (that describes the effects of the Coulomb repulsion and normally ranges between 0 and 0.242). The concentration of defects in the material was also taken into account by using a scattering parameter γd=0.25 meV obtained by fitting the temperature dependence of the local spin susceptibility6.

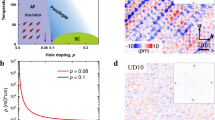

(a) The electron–boson coupling constant λ calculated as a function of the characteristic boson energy Ω0 for selected physically reasonable values of the Coulomb pseudopotential, that is, μ*=0.00 (black), μ*=0.10 (red), μ*=0.15 (green) and μ*=0.20 (blue). The critical temperature is fixed at the experimental value Tc=18.5 K. The concentration of defects in the material was taken into account by using a scattering parameter γd=0.25 meV obtained by fitting the temperature dependence of the local spin susceptibility. The shape of the electron–boson spectral function is shown in the inset. (b) The values of the low-temperature gap Δ(T→0) calculated for all sets of Ω0, λ and μ* values corresponding to the curves in (a). The colours of the curves refer to the corresponding value of μ*, as in (a). The grey region indicates the range of gap values extracted from the point-contact Andreev-reflection measurements. The corresponding range of allowed Ω0 is determined by the intersections of the black (minimum μ*) and blue (maximum μ*) curves with the grey region indicated by dots. It turns out that Ω0 ranges between 5.3 and 8.5 meV. The maximum and minimum values of the coupling constant compatible with these values are λmin=2.2 and λmax=3.7. The range of spin-fluctuation energies measured by NMR is indicated by the horizontal bar.

We first solved the Eliashberg equations in the imaginary-axis representation (explicitly written in the Supplementary Methods) to determine the pairs of λ and Ω0 values that, for some given values of μ* between 0 and 0.2, give the experimental Tc=18.5 K. In Fig. 5a these pairs are represented by solid lines in the (Ω0, λ) plane.

Then, we solved the real-axis Eliashberg equations to calculate the low-temperature gap Δ(T→0) for all sets of Ω0, λ and μ* previously determined. The gap values are shown as a function of Ω0 in Fig. 5b. The range of Ω0 values that are physically compatible with the PCARS results are finally determined, as shown in Fig. 5b, by intersecting the calculated Δ(T→0) versus Ω0 curves with the experimental gap range (grey region). The result is  . This interval largely overlaps with the range of spin-fluctuation energies (from 4 to 8 meV) determined by NMR measurements45; this clearly indicates that spin fluctuations do possess the right energies to explain the experimental PCARS results. The intersection between the two ranges provides a conservative range for the characteristic boson energy, that is,

. This interval largely overlaps with the range of spin-fluctuation energies (from 4 to 8 meV) determined by NMR measurements45; this clearly indicates that spin fluctuations do possess the right energies to explain the experimental PCARS results. The intersection between the two ranges provides a conservative range for the characteristic boson energy, that is,  . The corresponding range of λ values, as shown in Fig. 5, turns out to be

. The corresponding range of λ values, as shown in Fig. 5, turns out to be  . The line in Fig. 4b was obtained by taking Ω0=6.5 meV, μ*=0, and using an electron–boson coupling constant λ=2.37. The slight gap increase at low temperature is a consequence of the strong electron–boson coupling46. Further details of the calculations are given in the Supplementary Methods.

. The line in Fig. 4b was obtained by taking Ω0=6.5 meV, μ*=0, and using an electron–boson coupling constant λ=2.37. The slight gap increase at low temperature is a consequence of the strong electron–boson coupling46. Further details of the calculations are given in the Supplementary Methods.

PCARS measurements on crystals with reduced Tc

As a test of the reliability and generality of the results discussed so far, we also performed PCARS measurements in 242PuCoGa5 crystals featuring a lower bulk  , K, due to the presence of Sb impurities (<1%). The point contacts in this case were made by placing a small drop of Ag conductive paste on the side surface of the plate-like crystals. Fig. 6a shows the conductance curves of a Ag/242PuCoGa5 contact with RN=6.9 Ω measured as a function of temperature. The curves are vertically offset for clarity; as in the cases discussed for the crystals with Tc=18.1 K, there is no shift of the tails at increased temperature. The Andreev signal disappears at some temperature between 14.5 K and 14.7 K, that is,

, K, due to the presence of Sb impurities (<1%). The point contacts in this case were made by placing a small drop of Ag conductive paste on the side surface of the plate-like crystals. Fig. 6a shows the conductance curves of a Ag/242PuCoGa5 contact with RN=6.9 Ω measured as a function of temperature. The curves are vertically offset for clarity; as in the cases discussed for the crystals with Tc=18.1 K, there is no shift of the tails at increased temperature. The Andreev signal disappears at some temperature between 14.5 K and 14.7 K, that is,  .

.

(a) Temperature dependence of the conductance curves of a point contact with RN=6.9 Ω made on a 242PuCoGa5 crystal with reduced Tc=14.5 K. The curves are vertically offset for clarity. (b) Two examples of low-temperature normalized conductance curves in two contacts on the same crystal (symbols). The normal-state resistance and the Andreev critical temperature are RN=6.9 Ω,  (top curve) and RN=18.8 Ω,

(top curve) and RN=18.8 Ω,  (bottom curve). Lines represent the best fit of the spectra within the d-wave 2D-BTK model. The values of the fitting parameters are: Δ=4.2 meV, Γ=3.7 meV, Z=0.325 and α=π/12 for the top curve, and Δ=3.63 meV, Γ=3.08 meV, Z=0.56 and α=π/11 for the bottom curve. (c) Temperature dependence of the gap extracted from the fit of the conductance curves of the contact with RN=18.8 Ω (symbols). The solid line is the corresponding Δ(T) function calculated within the Eliashberg theory by assuming Ω0=6.5 meV and a coupling constant λ=2.37.

(bottom curve). Lines represent the best fit of the spectra within the d-wave 2D-BTK model. The values of the fitting parameters are: Δ=4.2 meV, Γ=3.7 meV, Z=0.325 and α=π/12 for the top curve, and Δ=3.63 meV, Γ=3.08 meV, Z=0.56 and α=π/11 for the bottom curve. (c) Temperature dependence of the gap extracted from the fit of the conductance curves of the contact with RN=18.8 Ω (symbols). The solid line is the corresponding Δ(T) function calculated within the Eliashberg theory by assuming Ω0=6.5 meV and a coupling constant λ=2.37.

Figure 6b reports the normalized low-temperature conductance of the same contact (top, symbols) and that of a different contact with RN=18.8 Ω and  (bottom, symbols). The shape of these curves, with a zero-bias maximum, confirms that the gap has a d-wave symmetry. It is worth noting that these spectra (as well as all those obtained in crystals with reduced Tc) show a strongly reduced Andreev signal with respect to the ideal case: the excess conductance at zero bias is <10% of the normal-state conductance. A similar effect is commonly observed in heavy-fermion superconductors24,31 and has been reported, in particular, for the isostructural compound CeCoIn526,47. According to ref. 31, this reduction might be explained by assuming that a fraction of the injected current tunnels into a non-superconducting band or set of states and does not contribute to Andreev reflection. In our case it seems logical, however, not to ascribe the small signal to intrinsic phenomena but, rather, to the greater amount of disorder and impurities of these samples with respect to the purest crystals (where instead the signal is very high) or to the use of the Ag paste instead of the Au wire as a counterelectrode. In either case, the broadening parameter Γ of the 2D-BTK model can be phenomenologically used to account for extrinsic inelastic scattering. A specific model for diffusive metal/d-wave superconductor48 could be used as well, with no major changes in the conclusions.

(bottom, symbols). The shape of these curves, with a zero-bias maximum, confirms that the gap has a d-wave symmetry. It is worth noting that these spectra (as well as all those obtained in crystals with reduced Tc) show a strongly reduced Andreev signal with respect to the ideal case: the excess conductance at zero bias is <10% of the normal-state conductance. A similar effect is commonly observed in heavy-fermion superconductors24,31 and has been reported, in particular, for the isostructural compound CeCoIn526,47. According to ref. 31, this reduction might be explained by assuming that a fraction of the injected current tunnels into a non-superconducting band or set of states and does not contribute to Andreev reflection. In our case it seems logical, however, not to ascribe the small signal to intrinsic phenomena but, rather, to the greater amount of disorder and impurities of these samples with respect to the purest crystals (where instead the signal is very high) or to the use of the Ag paste instead of the Au wire as a counterelectrode. In either case, the broadening parameter Γ of the 2D-BTK model can be phenomenologically used to account for extrinsic inelastic scattering. A specific model for diffusive metal/d-wave superconductor48 could be used as well, with no major changes in the conclusions.

Solid lines in Fig. 6b depict two representative fits of the experimental data within the 2D-BTK model used so far. The fitting parameters are indicated in the legend of the same figure. As expected, the fit requires a large Γ value, although still smaller than the corresponding Δ. Taken all together, the PCARS measurements in these crystals indicate a low-temperature gap Δ=3.9±0.3 meV, corresponding to a gap ratio 2Δ/kBTc=6.2±0.4. The latter differs only slightly (about 3%) from that determined in the crystals with the highest Tc, supporting the robustness of the picture that emerges from our measurements.

Figure 6c shows an example of the temperature dependence of the gap extracted from the fit (symbols). The line is calculated within the Eliashberg theory, using the same spectral function and the same values of Ω0, λ and μ* as in Fig. 4b. The different Tc and the different gap amplitude arise only from the larger value of the quasiparticle scattering rate γd included in the Eliashberg equations to account for the disorder: while Tc=18.5 K was obtained by using γd=0.25 meV, the reduced Tc=14.5 K of this particular contact requires γd=1.6 meV. This indicates substantial consistency of all the results and generality of the conclusions drawn about the mechanisms of superconductivity in PuCoGa5.

Discussion

A scenario where magnetic fluctuations are responsible for the formation of the Cooper pairs in PuCoGa5 must be reconciled with the observed temperature-independent magnetic susceptibility5 that points to vanishing local moments at the Pu sites. A plausible explanation is provided by electronic structure calculations combining the LDA with the exact diagonalization (ED)49 of a single-impurity Anderson model50 that is composed of a Pu 5f shell (the impurity) and of those extended states that hybridize with this shell and form the so-called electronic bath. In this approach, the band structure obtained by the relativistic version of the full-potential linearized augmented plane wave method51 is consistently extended to account for the full structure of the f-orbital atomic multiplets and their hybridization with the conduction bands52. Details on this procedure are given in the Supplementary Methods; the bandstructure and the FS are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2.

The calculated f-orbital density of states (DOS) is shown in Fig. 7. Below the Fermi energy EF, the DOS exhibits a three-peak structure that is typical for Pu and for a number of its compounds. Our DOS is in reasonably good agreement with the results of the non-crossing approximation reported in ref. 53 and with photoemission experiments performed on single crystals54 and on thin film samples55, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3.

The 5f-electron DOS at the Pu atom in PuCoGa5 (red) and its projections onto the states with the total angular momentum j=5/2 (blue) and j=7/2 (black). Note the three peaks labelled A, B and C that are characteristic for many Pu compounds. The inset shows the valence histogram obtained by the projection of the LDA+ED solution onto the Pu atomic orbitals.

The inset of Fig. 7 shows the valence histogram calculated by projecting the ground state of the Anderson impurity model  onto the Pu atomic eigenstates

onto the Pu atomic eigenstates  that correspond to an integer 5f-shell occupation nm. The plotted probabilities Pm determine the 5f-orbital valence

that correspond to an integer 5f-shell occupation nm. The plotted probabilities Pm determine the 5f-orbital valence  The highest obtained probability is P5=0.63, followed by P6=0.33. In addition, there are small but non-zero probabilities P4=0.03 and P7=0.01. The Pu 5f shell has thus an intermediate-valence nature, being a mixture of a magnetic 5f5 sextet and a non-magnetic 5f6 singlet. Similar electronic structures have been suggested for δ-Pu56 and several rare-earth-based materials. In the latter case, if the intermediate-valence state involves a non-magnetic atomic configuration, the low-T magnetic susceptibility is temperature independent57. The susceptibility of PuCoGa5 is also found to be temperature independent at low temperatures5.

The highest obtained probability is P5=0.63, followed by P6=0.33. In addition, there are small but non-zero probabilities P4=0.03 and P7=0.01. The Pu 5f shell has thus an intermediate-valence nature, being a mixture of a magnetic 5f5 sextet and a non-magnetic 5f6 singlet. Similar electronic structures have been suggested for δ-Pu56 and several rare-earth-based materials. In the latter case, if the intermediate-valence state involves a non-magnetic atomic configuration, the low-T magnetic susceptibility is temperature independent57. The susceptibility of PuCoGa5 is also found to be temperature independent at low temperatures5.

The Pu f shell carries a non-vanishing average magnetic moment as it fluctuates between the singlet and the sextet. At the same time, the ground state  as a whole is a singlet characterized by all angular momenta equal to zero (S=L=J=0). The fluctuations of the momenta in the f shell are accompanied by compensating fluctuations in the bath, which can be viewed as a manifestation of the Kondo physics. In analogy to a Kondo singlet state, the magnetic susceptibility is anticipated to behave as

as a whole is a singlet characterized by all angular momenta equal to zero (S=L=J=0). The fluctuations of the momenta in the f shell are accompanied by compensating fluctuations in the bath, which can be viewed as a manifestation of the Kondo physics. In analogy to a Kondo singlet state, the magnetic susceptibility is anticipated to behave as  , which remains constant for

, which remains constant for  , as observed experimentally5. In addition, our band-structure calculations suggest an antiferromagnetic instability due to the presence of a FS sheet with a negative second derivative of the Drude plasma energy, as shown in Supplementary Table S1.

, as observed experimentally5. In addition, our band-structure calculations suggest an antiferromagnetic instability due to the presence of a FS sheet with a negative second derivative of the Drude plasma energy, as shown in Supplementary Table S1.

This analysis indicates that the d-wave superconducting coupling in PuCoGa 5 can be mediated by spin fluctuations—even though the microscopic magnetization is temperature-independent—because such fluctuations would involve a time-dependent 5f local moment dynamically compensated by a moment formed in the surrounding cloud of conduction electrons.

Methods

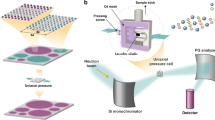

Point-contact Andreev-reflection spectroscopy

Point-contact spectroscopy is a simple but very powerful tool for the investigation of the superconducting OP that, in past decades, has been successfully applied to many families of superconductors, namely cuprates, borocarbides, heavy fermions and the recently discovered iron-based compounds. The technique consists in measuring the differential conductance of a N–S contact between a normal metal (N) and a superconductor (S) whose radius a is smaller than both the electronic mean free path and the coherence length in S. In these conditions, an electron travels through the contact ballistically, that is, without being diffused, so that if a voltage V is kept at the junction's ends, it enters the superconductor with a maximum excess energy eV. When this energy is smaller than the gap in the superconductor, Δ, the electron cannot propagate in S as an electron-like quasiparticle (ELQ), because it finds no available states. Thus, it forms a Cooper pair and a hole is retro-reflected in N.

If the OP is isotropic (Fig. 3a, top) and there is no potential barrier at the interface, this results in a doubling of the conductance for |V|≤Δ/e. If |eV|>Δ, the conductance decreases again towards the value it would have if the superconductor were in the normal state. This is shown in the top curve of Fig. 3b, calculated for the case of an ideal barrier-less junction by using the BTK model37 generalized to the 2D case39,40. If a potential barrier is present (that is, the dimensionless barrier parameter Z has a finite value), other phenomena take place that can give rise to a normal reflection of the incoming electron, and also to the transmission of hole-like quasiparticles in S. As a result, the conductance presents two maxima at approximately V=±Δ/e and a zero-bias minimum, as shown in Fig. 3b.

If the OP is anisotropic, electrons injected along different directions may experience different pairing amplitudes. Figure 3a (bottom) shows for example an OP with  -wave symmetry,

-wave symmetry,  , where θ is the azimuthal angle in the kx, ky plane of the reciprocal space and φ is the inclination angle. In cases like this, the shape of the conductance curves does not depend only on the height of the potential barrier at the interface, but also on the direction of (main) current injection with respect to the k-space axes.

, where θ is the azimuthal angle in the kx, ky plane of the reciprocal space and φ is the inclination angle. In cases like this, the shape of the conductance curves does not depend only on the height of the potential barrier at the interface, but also on the direction of (main) current injection with respect to the k-space axes.

The curves shown in Fig. 3c,d represent the theoretical conductance curves of a normal metal/d-wave superconductor calculated by using the 2D-BTK model. In this approach, the FS is supposed to be perfectly cylindrical (with its axis parallel to the kz axis), the dependence of the OP on φ is disregarded, and the direction of current injection is simply defined by the angle α between the normal to the interface n and the kx axis. Note, however, that individual electrons approach the N–S junction from any direction, specified by the angle θN (0≤θN<π/2) between their wavevectors and n39. In this paper, in view of the mostly 2D shape of the largest FS sheets (and also for simplicity), we have always used this model. In ref. 40 it is seen that this approximation, with respect to a more refined 3D model, generally gives rise to an overestimation of the parameter Z, which is not relevant in our analysis.

If α=0, the normal n is parallel to the kx axis; for any angle of incidence θN of the incoming electron, ELQ and HLQ transmitted in S with angles +θS and −θS with respect to n feel the same OP, in amplitude and sign. However, because of the angular dependence of the gap, the conductance is doubled only at zero bias where it shows a characteristic cusp. If there is no barrier, the same shape is obtained for any value of α: the conductance curve always looks like the top curve in Fig. 3c. If instead a barrier is present, for any α≠0 some values of θN exist for which HLQ and ELQ feel OPs of opposite sign39. This gives rise to constructive interference between HLQ and ELQ that results in localized zero-energy states (Andreev bound states). These states manifest themselves in the conductance giving rise to a ZBCP. When α=π/4 the current is injected along the nodal direction, all ELQ and HLQ interfere and the ZBCP is maximum. Examples of calculated (normalized) conductance curves assuming α=π/4 and α=π/8 are shown in Fig. 3c,d for increasing values of Z.

All the curves in Fig. 3 were calculated at T=0 and in ideal conditions (perfectly ballistic conduction, no broadening effects). When the 2D-BTK model is used to fit experimental data, however, the calculated conductance at T=0 must be convoluted with the Fermi function40. Moreover, an additional broadening parameter Γ must be often included in the model to account for the finite lifetime of quasiparticles and other extrinsic broadening effects (like inelastic scattering processes occurring near the N–S interface)40.

Growth and characterization of the samples

The 239PuCoGa5 crystals were grown by a flux method and characterized by X-ray diffraction, electrical resistivity, magnetization and specific heat measurements. Magnetic susceptibility and resistivity measurements were performed in commercial Quantum Design platforms (MPMS 7-T SQUID and PPMS-9T). The crystals were submitted to a thermal treatment to anneal the self-radiation damage. Supplementary Fig. S1 shows the temperature dependence of the electrical resistivity measured for one of these crystals immediately after a thermal treatment. All the samples exhibited a critical temperature very close to the optimal value Tc=18.5 K.

The 242PuCoGa5 single crystals were grown from the melt using 242PuSb instead of metallic 239Pu as starting material, leading to traces of Sb (<1%) and to a reduced Tc=14.5 K. The use of the 242Pu isotope avoids effects from radiation damage and self heating, especially at low temperature. Magnetization, transport properties and heat capacity confirm their similarity with freshly synthesized single crystals of 239PuCoGa55.

Fabrication of point contacts

PCARS measurements in 239PuCoGa5 were started within 1 day from the thermal treatment. The point contacts were made between a fresh, mirror-like surface of the crystal (just exposed by breaking the sample) and a thin Au wire (about 10 μm in diameter). The uneven broken surface on which the contact is made prevents a fine control of the direction of current injection with respect to the crystallographic axes. However, as shown above, this does not prevent the unambiguous determination of the amplitude and symmetry of the OP.

Point contacts in 242PuCoGa5 with Tc=14.5 K were made on the side surface of the plate-like crystals so as to inject the current mainly along the ab planes. Unlike in the purest samples, here we used a small spot of Ag conducting paste between the Au wire and the sample to act as the N electrode and also to mechanically stabilize the contacts40.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Daghero, D. et al. Strong-coupling d-wave superconductivity in PuCoGa5 probed by point contact spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 3:786 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1785 (2012).

References

Sarrao, J. L. et al. Plutonium-based superconductivity with a transition temperature above 18 K. Nature 420, 297–299 (2002).

Bauer, E. D. et al. Structural tuning of unconventional superconductivity in PuMGa5 (M=Co,Rh). Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 147005 (2004).

Heffner, R. H. et al. μSR studies of Pu metal and the Pu-based superconductor PuCoGa5 . J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 75S, 14–19 (2006).

Morris, G. D. et al. μSR studies of the superconducting order parameter in PuCoGa5 . Physica B 374–375, 180–183 (2006).

Hiess, A. et al. Electronic state of PuCoGa5 and NpCoGa5 as probed by polarized neutrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 076403 (2008).

Curro, N. J. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in PuCoGa5 . Nature 434, 622–625 (2005).

Opahle, I. & Oppeneer, P. M. Superconductivity caused by the pairing of plutonium 5f electrons in PuCoGa5 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 157001 (2003).

Maehira, T., Hotta, T., Ueda, K. & Hasegawa, A. Electronic structure and the fermi surface of PuCoGa5 and NpCoGa5 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 207007 (2003).

Opahle, I., Elgazzar, S., Koepernik, K. & Oppeneer, P. M. Electronic structure of the Pu-based superconductor PuCoGa5 and of related actinide-115 compounds. Phys. Rev. B 70, 104504 (2004).

Tanaka, K., Ikeda, H. & Yamada, K. Theory of superconductivity in PuCoGa5 . J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 73, 1285–1289 (2004).

Shick, A. B., Janiš, V. & Oppeneer, P. M. Effect of coulomb correlations on the electronic structure of PuCoGa5 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 016401 (2005).

Pourovskii, L. V., Katsnelson, M. I. & Lichtenstein, A. I. Correlation effects in electronic structure of PuCoGa5 . Phys. Rev. B 73, 060506 (2006).

Zhu, J.- X. et al. Electronic structure and correlation effects in PuCoIn5 as compared to PuCoGa5 . Europhys. Lett 97, 57001 (2012).

Shick, A. B., Rusz, J., Kolorenč, J., Oppeneer, P. M. & Havela, L. Theoretical investigation of electronic structure, electric field gradients, and photoemission of PuCoGa5 and PuRhGa5 superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 83, 155105 (2011).

Singh, D. J. & Du, M.- H. Density functional study of LaFeAsO1−xFx: a low carrier density superconductor near itinerant magnetism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 237003 (2008).

Bang, Y., Balatsky, A. V., Wastin, F. & Thompson, J. D. Possible pairing mechanisms of PuCoGa5 superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 70, 104512 (2004).

Boulet, P. et al. Tuning of the electronic properties in PuCoGa5 by actinide (U, Np) and transition-metal (Fe, Rh, Ni) substitutions. Phys. Rev. B 72, 104508 (2005).

Ohishi, K. et al. Muon spin rotation measurements of the superfluid density in fresh and aged superconducting PuCoGa5 . Phys. Rev. B 76, 064504 (2007).

Jutier, F. et al. Possible mechanism of superconductivity in PuCoGa5 probed by self-irradiation damage. Phys. Rev. B 77, 024521 (2008).

Monthoux, P., Pines, D. & Lonzarich, G. G. Superconductivity without phonons. Nature 450, 1177–1183 (2007).

Pfleiderer, C. Superconducting phases of f -electron compounds. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 1551–1624 (2009).

Flint, R., Dzero, M. & Coleman, P. Heavy electrons and the symplectic symmetry of spin. Nat. Phys. 4, 643–648 (2008).

Talbayev, D. et al. Hybridization and superconducting gaps in the heavy-fermion superconductor PuCoGa5 probed via the dynamics of photoinduced quasiparticles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 227002 (2010).

Naidyuk, Yu.G. & Yanson, I. K. Point-contact spectroscopy of heavy-fermion systems. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 10, 8905 (1998).

Daghero, D., Tortello, M., Ummarino, G. A. & Gonnelli, R. S. Directional point-contact Andreev-reflection spectroscopy of Fe-based superconductors: Fermi surface topology, gap symmetry and electron-boson interaction. Rep. Prog. Phys. 74, 124509 (2011).

Park, W. K., Sarrao, J. L., Thompson, J. D. & Greene, L. H. Andreev reflection in heavy-fermion superconductors and order parameter symmetry in CeCoIn5 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 177001 (2008).

Nowack, A. et al. Point-contact spectra of heavy-fermion superconductors UBe13 and UPt3 . Phys. Rev. B 36, 2436 (1987).

Hasselbach, K., Kirtley, J. R. & Lejay, P. Point-contact spectroscopy of superconducting URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. B 46, 5826 (1992).

Rodrigo, J. G., Guinea, F., Vieira, S. & Aliev, F. G. Point-contact spectroscopy of superconducting URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. B 55, 14318 (1997).

Goll, G., Löhneysen, H. v., Yanson, I. K. & Taillefer, L. Anisotropy of point-contact spectra in the heavy-fermion superconductor UPt3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 2008 (1993).

Fogelström, M., Park, W. K., Greene, L. H., Goll, G. & Graf, M. J. Point-contact spectroscopy in heavy-fermion superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 82, 014527 (2010).

Coleman, P. Handbook of magnetism and advanced magnetic materials. In Fundamentals and Theory Vol 1 (eds Kronmuller, H. & Parkin, S.) 95–148 (John Wiley and Sons, 2007).

Deutscher, G. Andreev-Saint-James reflections: a probe of cuprate superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 109–135 (2005).

Wei, J. Y. T., Yeh, N.- C., Garrigus, D. F. & Strasik, M. Directional tunneling and Andreev reflection on YBa2Cu3O7−δ single crystals: predominance of d-wave pairing symmetry verified with the generalized Blonder, Tinkham, and Klapwijk theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 2542–2545 (1998).

Biswas, A. et al. Evidence of a d- to s-wave pairing symmetry transition in the electron-doped cuprate superconductor Pr2−xCexCuO4 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 207004 (2002).

Qazilbash, M. M., Biswas, A., Dagan, Y., Ott, R. A. & Greene, R. L. Point-contact spectroscopy of the electron-doped cuprate superconductor Pr2−xCexCuO4: the dependence of conductance-voltage spectra on cerium doping, barrier strength, and magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 68, 024502 (2003).

Blonder, G. E., Tinkham, M. & Klapwijk, T. M. Transition from metallic to tunneling regimes in superconducting microconstrictions: excess current, charge imbalance, and supercurrent conversion. Phys. Rev. B 25, 4515–4532 (1982).

Kashiwaya, S., Tanaka, Y., Koyanagi, M. & Kajimura, K. Theory for tunneling spectroscopy of anisotropic superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 53, 2667–2676 (1996).

Kashiwaya, S. & Tanaka, Y. Tunnelling effects on surface bound states in unconventional superconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 63, 1641 (2000).

Daghero, D. & Gonnelli, R. S. Probing multiband superconductivity by point-contact spectroscopy. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 23, 043001 (2010).

Eliashberg, G. M. Interactions between electrons and lattice vibrations in a superconductor. Sov. Phys. JETP 11, 696–702 (1960).

Carbotte, J. P. Properties of boson-exchange superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 62, 1027–1157 (1990).

Schachinger, E. & Carbotte, J. P. Microwave conductivity of YBa2Cu3O6.99 including inelastic scattering. Phys. Rev. B 65, 064514 (2002).

Monthoux, P., Balatsky, A. V. & Pines, D. Toward a theory of high-temperature superconductivity in the antiferromagnetically correlated cuprate oxides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 3448–3451 (1991).

Baek, S.-H. et al. Anisotropic spin fluctuations and superconductivity in '115' heavy-fermion compounds: 59Co NMR Study in PuCoGa5 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 217002 (2010).

Ummarino, G. A. & Gonnelli, R. S. Real-axis direct solution of the d-wave Eliashberg equations and the tunneling density of states in optimally doped Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+x . Physica C 328, 189 (1999).

Goll, G. et al. Point-contact spectroscopy on heavy-fermion superconductors. Physica B 378–380, 665–668 (2006).

Shigeta, I., Tanuma, Y., Asano, Y., Hiroi, M. & Tanaka, Y. Tunneling study through analysis of spatial variations of the pair potential in diffusive normal metal/insulator/high-Tc superconductor junctions. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 69, 3042 (2008).

Kolorenč, J. Private communication.

Hewson, A. C. The Kondo Problem to Heavy Fermions (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Shick, A. B. & Pickett, W. E. Magnetism, spin-orbit coupling, and superconducting pairing in UGe2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 300–303 (2001).

Shick, A. B., Kolorenč, J., Lichtenstein, A. I. & Havela, L. Electronic structure and spectral properties of Am, Cm, and Bk: charge-density self-consistent LDA+HIA calculations in the FP-LAPW basis. Phys. Rev. B 80, 085106 (2009).

Pezzoli, M. E., Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Neutron magnetic form factor in strongly correlated materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 016403 (2011).

Joyce, J. J. et al. Photoemission and the electronic structure of PuCoGa5 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 176401 (2003).

Eloirdi, R. et al. Photoelectron spectroscopy study of PuCoGa5 thin films. J. Nucl. Mater. 385, 8–10 (2009).

Shim, J. H., Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Fluctuating valence in a correlated solid and the anomalous properties of δ-plutonium. Nature 446, 513–516 (2007).

Lawrence, J. M., Riseborough, P. S. & Parks, R. D. Valence fluctuation phenomena. Rep. Prog. Phys. 44, 1–84 (1981).

Acknowledgements

This work has been performed at the Institute for Transuranium Elements within its 'Actinide User Laboratory' program, with financial support to users provided by the European Commission. The support from Czech Republic Grants GACR P204/10/0330 and GAAV IAA100100912 is thankfully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.C., D.D. and M.T. designed the research; D.D., M.T. and J.-C.G.performed PCARS experiments; R.E., J.-C.G. and E.C. prepared and characterized the samples; G.A.U. performed Eliashberg calculations, A.B.S., J.K. and A.I.L. performed ab initio calculations; D.D., M.T., J.-C.G.,E.C., R.C., G.A.U. and A.B.S. analysed and interpreted the data; and R.C., D.D., M.T., A.B.S. and J.K. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S3, Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 988 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Daghero, D., Tortello, M., Ummarino, G. et al. Strong-coupling d-wave superconductivity in PuCoGa5 probed by point-contact spectroscopy. Nat Commun 3, 786 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1785

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1785

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.