Abstract

Large-area graphene films are best synthesized via chemical vapour and/or solid deposition methods at elevated temperatures (~1,000 °C) on polycrystalline metal surfaces and later transferred onto other substrates for device applications. Here we report a new method for the synthesis of graphene films directly on SiO2/Si substrates, even plastics and glass at close to room temperature (25–160 °C). In contrast to other approaches, where graphene is deposited on top of a metal substrate, our method invokes diffusion of carbon through a diffusion couple made up of carbon-nickel/substrate to form graphene underneath the nickel film at the nickel–substrate interface. The resulting graphene layers exhibit tunable structural and optoelectronic properties by nickel grain boundary engineering and show micrometre-sized grains on SiO2 surfaces and nanometre-sized grains on plastic and glass surfaces. The ability to synthesize graphene directly on non-conducting substrates at low temperatures opens up new possibilities for the fabrication of multiple nanoelectronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graphene has generated enormous scientific curiosity owing to its ultrathin geometry1,2, quantum electronic transport2,3, bandgap opening4,5, excellent thermal conductivity6 and high mechanical strength7. Among all of the potential applications for graphene, realization of graphene-based flexible electronic display technology appears to be closer to reality8. Currently, large-area graphene films are best synthesized via pyrolytic cracking of hydrocarbon gases8,9,10,11 and/or a solid deposition method12 at elevated temperatures (~1,000 °C) on polycrystalline metal surfaces and later transferred onto other substrates for the fabrication of devices. However, the high growth temperatures impose limitations on the choice of substrates and the subsequent transferability of as-grown layers influence device performance. Recently, bilayer graphene has been grown directly on insulating substrates at elevated temperatures (~1,000 °C) using spin-coated polymer films as solid source of carbon (C) with nickel (Ni) thin films on top or bottom of the polymer film13,14.

Here we describe a very low-temperature and transfer-free approach to controllably deposit graphene films onto desired substrates. Our synthesis methodology exploits the properties of a 'diffusion couple', wherein a Ni thin film is deposited first on the substrate, and solid C is then deposited on top of the Ni, and allowed to diffuse predominantly along grain boundaries (GBs) to create a thin graphene film at the Ni–substrate interface. To tune the structural and optoelectronic properties of the resulting graphene layers, we have engineered grain sizes of the Ni films on the substrate of choice. Our method allows for uniform and controllable deposition of wrinkle-free graphene films with micrometre-sized grains on SiO2 surfaces, and with nanometre-sized grains on plastic and glass. This study suggests that large-scale, device-ready graphene layers can be simply prepared without a transfer process on any arbitrary substrate at low temperatures—highly desirable for electronic and optoelectronic applications.

Results

Diffusion-assisted synthesis (DAS) method

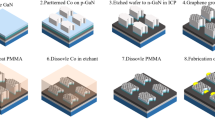

Figure 1a schematically illustrates our process, which we refer to as DAS. We demonstrate the applicability of this method using thermally oxidized Si(100), poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA)-covered SiO2, and commercially available glass as substrates. First, ~100-nm-thick film of polycrystalline Ni (poly-Ni) is deposited via electron-beam evaporation at temperatures as low as ~25 °C on PMMA and glass and at temperatures as high as ~400 °C on SiO2/Si(100). Ni thin films deposited on SiO2/Si(100) were annealed at ~1,000 °C in a H2 ambient to yielding a strong 111-texture and 5–20μm sized grains with smooth surfaces. Using Raman spectroscopy, we confirm that the surfaces of Ni (after annealing) and SiO2 (after removal of the metal) are free of crystalline C. In case of Ni thin films deposited at room temperature, the average grain size is about 40–50 nm. Details of the deposition, morphology and crystallinity of the Ni films are presented in Methods and Supplementary Figures S1 and S2. The choice of Ni is motivated by the facts that it has a high solubility for C and Ni(111) is nearly lattice-matched with basal planes of graphite, both of which facilitate commensurate epitaxial growth of graphene15,16. Solid C is supplied from a paste composed of graphite powder (Aldrich, product 496596) dispersed in ethanol. (Highly oriented pyrolytic graphite can also be used as C source but we obtained better results with the paste.) To ensure efficient contact at the C–Ni interface and stimulate the C-C bond breaking on catalytic Ni(111) surface17,18, a pressure (<1 MPa) is uniformly applied by mechanically clamping the C–Ni/substrate diffusion couple using a molybdenum holding stage. The samples are then sealed in a quartz tube filled with inert argon gas (or with air) and heated for short periods (t=1–10 min) at temperatures T between 25 and 260 °C. Substrate temperatures are measured using a k-type thermocouple directly connected to the sample holder and are accurate to within 10 °C. Following graphene growth, the C-Ni diffusion couple is etched away using an aqueous solution of FeCl3 leaving behind a graphene film on the desired substrate. The details of this process are presented in Methods.

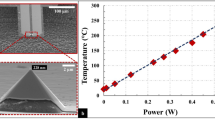

(a) Schematic drawing of the DAS process for directly depositing graphene films on nonconducting substrates. The diagrams represent (from left to right) the elementary steps in the DAS process, including deposition (and annealing) of Ni thin films on desired substrates (SiO2/Si or PMMA, glass), preparation of diffusion couple of C–Ni/substrate, annealing in Ar or air (25–260 °C) to form C–Ni/graphene/substrate and formation of graphene on desired substrates by etching away C–Ni diffusion couple, respectively. Representative (b) optical microscopy (OM) image, (c) Raman spectra from red, blue and green spots showing the presence of one, two and three layers of graphene, respectively, (from bottom to top) and (d) Raman map image of the G/2D bands of graphene grown at temperature T=160 °C for 5 min on SiO2(300 nm)/Si substrate. Scale bars, 4 μm (b and d). (e) Representative SEM image of graphene grown at T=160 °C for 5 min on SiO2(300 nm)/Si substrate (scale bar, 100 μm). (f) Higher magnification SEM image of e, showing the presence of 1 ML (red dot), 2 ML (blue dot) graphene and multilayer graphene ridges (white dot); (scale bar, 10 μm). (g) Typical room temperature IDS-VG curve at VDS=10 mV from a DAS-grown ML graphene-based back-gated FET device. The estimated carrier (hole) mobility is ~667 cm2 V−1s−1 at room temperature and it shows weak p-type behaviour. The inset shows optical microscopy image of this device and the scale bar is 10 μm. IDS, drain-source current; VDS, drain-source voltage; VG, gate voltage.

Synthesis and characterization of graphene films on SiO2–Si substrates

Figure 1b–f shows typical results of surface morphology and Raman spectra, respectively of the graphene layers on SiO2/Si(100) obtained at T=160 °C and t=5 min. The three Raman spectra, colour coded for clarity, in Figure 1c are obtained from the three corresponding coloured circles. They show three primary features: a D band at ~1351 cm−1, a G band at ~1592 cm−1 and a 2D band at ~2685 cm−1, all expected peak positions for graphene. Film thicknesses are determined by measuring the ratio of G-to-2D peak intensities (IG/I2D) and the full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) values of the symmetric 2D band. For the spectra of monolayer (ML)-area graphene, we obtain (1) IG/I2D < 0.5 and (2) the FWHM value of ~38 cm−1 for the 2D band, consistent with previous reports9,11. The associated G/2D band map in Figure 1d illustrates the uniformity of graphene films over large areas (~320 μm2) covered mostly with 1ML and 2ML graphene as identified by the IG/I2D < 0.5 and IG/I2D≈1, respectively. There are, however, a few regions with multilayer graphene (for example, the region highlighted by the white dot in Fig. 1f) and we refer to them as graphene ridges. From optical and scanning electron microscopy (OM and SEM) images acquired from the samples, we note that the as-synthesized graphene films are wrinkle-free and smooth over large areas. Interestingly, we find that the morphologies of regions covered with mono- and bi-layer graphene resemble those of the grains, and the multilayer graphene ridges, the GBs in the Ni thin films. These observations suggest that multilayer graphene growth is favoured at defects such as GBs. This is plausible as GB diffusion is typically faster than bulk diffusion and GBs can serve as nucleation sites19,20.

The electrical properties of graphene layers on SiO2/Si(100) obtained at T=160 °C and t=5 min have been evaluated with back-gated graphene-based field-effect transistor (FET) devices and typical data for the FET devices are shown in Figure 1g and Supplementary Figure S3a. The 'V' shape of the ambipolar transfer characteristics and the shift of neutrality point to positive gate voltage, that is, weak p-type behaviour1,12,21, in ambient conditions are observed, all expected electrical properties for graphene-based FETs. The estimated carrier (hole) mobility of this particular device in ambient conditions is ~667 cm2 V−1 s−1 at room temperature, suggesting that the as-synthesized graphene films are of reasonable quality.

Using our approach, we have synthesized graphene layers over a range of temperatures between 25 and 260 °C. OM images and Raman spectroscopic measurements of G-to-2D intensity ratio (IG/I2D) and FWHM of G bands9 (Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Fig. S4) indicate that few-layer graphene films with similar quality can be obtained at all T, even at room temperature (Fig. 2a). However, the surface coverage of graphene on SiO2 shows a strong dependence on T, increasing linearly from ~60 to ~98% with increasing T from 25 to 260 °C as shown in Figure 2b. (The corresponding OM images of graphene on SiO2 grown at different T are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4.) We note that continuous graphene layers over large areas can only be obtained at T≥160 °C. The sheet resistance of graphene layers grown at T=160 °C, measured using transmission line model method22,23, is found to be ~1,000 Ω per square (Supplementary Fig. S3b), which makes the as-synthesized graphene promising as a transparent electrode material. We have also explored the possibility of using our approach to grow graphene in air instead of inert Ar atmospheres. Surprisingly, we find that the surface morphology, areal coverage and Raman structure (Fig. 2c) of the graphene films grown in Ar as well as in air are similar, demonstrating the potential of our approach to grow graphene in air at low temperatures.

(a) Raman spectra showing the presence of one (red), two (blue) and three (green) layers (from bottom to top) of graphene film grown at room temperature for 10 min on SiO2(300 nm)/Si substrate. (b) FWHM of G bands in Raman spectra (black squares) and the surface coverage (red circles) of graphene films grown for 10 min on SiO2 as a function of growth temperature T. For comparison, the FWHM of G band for a highly oriented pyrolytic graphite substrate is 15 cm−1. The insets show the optical microscopy images of few-layer graphene films grown at room temperature (left; scale bar, 20 μm) and at 205 °C (right) (scale bar, 100 μm) on SiO2(300 nm)/Si substrates. (c) Comparison of the Raman spectra of 1ML-area graphene films grown at T=25 °C (black), 60 °C (red) and 160 °C (green) in argon and at T=25 °C (blue), 160 °C (purple) in air (from bottom to top). (d) Representative low-magnification plan-view TEM image of graphene film grown at T=160 °C on SiO2 then transferred onto a TEM support grid (scale bar, 100 nm). Inset is a selected area diffraction pattern obtained from a wrinkle-free region highlighted by the dotted circle. Scale bar in inset is 5 1/nm.

Growth mechanism of graphene films in DAS process

So, how does graphene form at such low temperatures? We propose a mechanism for the growth of graphene layers in DAS as follows: to form graphene at the Ni–SiO2 interface, C from the solid source will have to diffuse through the Ni film and crystallize as graphene at the interface. Given that our temperatures are well below 260 °C, we rule out the possibility of graphene growth via C precipitation from the bulk that requires temperatures 460 °C or higher24. (In case of 460 °C≤T≤600 °C, we observed the formation of nanocrystalline graphene layers and the layers contain no graphene ridges at all, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S5.) Instead, we suggest the following: C atoms from solid C source have to diffuse through the Ni film. Previous experimental17,24 and theoretical17,18 studies indicate that Ni surface can catalyze the dissociation of C-C bonds and promote diffusion even at room temperature. The resulting C atoms are transported across the Ni film primarily along the GBs to the Ni–SiO2 interface19,20,25. Following Fisher19 and Balluffi and Blakely20, we estimate the ratio of two transport fluxes of C atoms through the Ni lattice (ňL) and along the GBs (ňGB) in 111-textured Ni films and it is evident that lower temperatures greatly favour GB diffusion relative to lattice diffusion, that is, ňGB»ňL (details of the calculations are presented in Methods). It is noted that the C atom transport along GBs in Ni films is highly susceptible to residual impurity concentrations such as hydrogen (Supplementary Fig. S6). Upon reaching the Ni–SiO2 interface, C atoms precipitate out as graphene at the GBs. This is consistent with the fact that for relatively short growth times (t≤1–3 min), independent of T (25–260 °C), we obtained graphene-free surfaces with traces of graphene ridges presumably along the GBs in Ni films. We verified the ridge composition to be graphene and not amorphous C using Raman spectroscopy and cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Supplementary Fig. S7). Excess C atoms reaching the graphene ridges, diffuse laterally along the graphene-Ni(111) interface and lead to the growth of graphene over large areas, driven by the strong affinity of C atoms to self-assemble and expand the sp2 lattice26. To understand the origin of the interfacial processes, we have performed density functional theory calculations on the transport of C atoms along the graphene-Ni(111) interface (details of the calculations are presented in Methods). We obtain an energy barrier of ~0.51 eV for diffusion of C atoms at the graphene–Ni(111) interface in agreement with earlier reports27,28, which indicates that the tracer diffusion coefficient (Dt) of C atoms is ~200 nm2 s−1 at room temperature, according to the Arrhenius equation.

The suggested graphene growth mechanism in DAS process is schematically illustrated in Fig. 3. Eventually, a continuous but polycrystalline graphene film forms at the Ni–SiO2 interface. Using a combination of TEM techniques including selected area diffraction pattern and dark-field TEM, we find that the grain sizes in graphene layers vary from a few hundred nanometres to a few micrometres (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. S8), and are comparable to those of Ni grains. Our results imply that we have more room for improvement in graphene quality by Ni GB engineering, that is, micrometre-scale or larger grain sizes in graphene layers can be obtained by creating macrocrystalline Ni films with GBs located far enough from each other and/or by wet chemical doping8,29 of the films with high controllability.

The diagrams represent (from left to right) the elementary steps of the process including dissociation of C–C bonds at C/Ni interface, diffusion of carbon atoms, followed by nucleation and growth of graphene. Graphene growth mechanism in case (a) 460 °C≤T≤600 °C; bulk diffusion of C atoms through Ni crystallites, leading to homogeneous nucleation at multiple sites resulting in the formation of nanocrystalline graphene film by precipitation and (b) T≤260 °C; preferential diffusion of C atoms via GBs in Ni, followed by heterogeneous nucleation at the defect sites and growth via lateral diffusion of C atoms along Ni/substrate interface.

Large-scale synthesis of graphene films on plastic and glass substrates

We demonstrate the applicability of our approach to prepare large-area graphene on non-conducting, plastic and glass substrates. To this purpose, we use T≤160 °C and do not anneal the Ni thin films so as to minimize thermal degradation of the substrates. Figure 4a shows typical surface morphology of graphene layers grown at T=60 °C and t=10 min on PMMA then transferred to SiO2(300 nm)/Si substrate (details of the transfer process are described in the Supplementary Methods). In contrast to graphene grown on SiO2, the graphene films on plastic and glass substrates are continuous over large areas at all T (even at room temperature), possibly due to the decrease in distance between GBs. The as-grown layers are nanocrystalline graphene, whose Raman structure has the following characteristics (Fig. 4b): two peaks centred at 1,359±4 cm−1 (the D band) and 1,594±2 cm−1 (the G band) with a relatively large FWHM and a ID/IG ratio of ~0.7±0.1, all expected for nanocrystalline graphene30. We have measured the thicknesses of graphene films transferred on to SiO2 substrates by atomic force microscopy. Figure 4c shows film thickness plotted as a function of T for samples grown at t=10, 30 and 60 min and all of our samples grown for t=10 min yield film thicknesses of 1.3±0.3 nm. In case of graphene layers grown on glass substrates at T≤60 °C for t=10 min, we obtain ~97.4% transmittance (Fig. 4d). Considering 2.3% absorption of incident white light in an individual graphene layer31, it can be inferred that these films are ML thick, in good agreement with atomic force microscopy data of as-grown graphene layers.

Representative (a) optical microscopy image of graphene film grown at T=60 °C for 10 min on PMMA then transferred to SiO2(300 nm)/Si substrate (scale bar, 100 μm). (b) Typical Raman spectra, with each of the colours corresponding to the coloured spots on the sample. Folded regions such as those highlighted by the green open circle are occasionally observed and are formed during transfer process. (c) The thicknesses of graphene films transferred onto SiO2(300 nm)/Si substrates after growth at T=25–160 °C for 10 min (black squares), 30 min (red circles) and 60 min (blue triangle) on PMMA. Error bars are the standard deviation of the thickness measured in 30 different edge regions in transferred graphene films. (d) Transmittances of graphene films grown at T=25 °C (black), 45 °C (red), 60 °C (blue) and 110 °C (green) for 10 min on glass substrates. The inset shows a photograph of graphene film grown at temperature T=60 °C.

Discussion

In our DAS process, the GBs in poly-Ni(111) films afford the C atoms the chance to preferentially diffuse to other surface at low temperatures. Upon reaching the Ni–substrate interface, C atoms precipitate out as graphene at the GBs (Supplementary Fig. S7) and growth occurs via lateral diffusion along the interface. This process gives rise to a continuous but polycrystalline graphene film. This finding indicates that we can control the average grain size of resulting graphene films by Ni GB engineering, that is, control the positions where graphene grains start to grow.

For graphene on Ni/SiO2, using thermal annealing process before DAS process, we enlarged the grain size of poly-Ni films by up to 5–20 μm (that is, create GBs located far enough from each other); thereby, the macrocrystalline graphene grains up to several micrometres in size are obtained, as confirmed by plan-view TEM analysis. However, for Ni on plastic and glass substrates, the as-deposited poly-Ni films were not annealed further, thereby the grain sizes were ~40–50 nm. As a result, resulting graphene films consist of grains of the order of nanometres. Similar results are also obtained in case we grow graphene films on SiO2 using as-deposited, unannealed poly-Ni(111) films.

Finally, we have also used polycrystalline Ni foils and obtained large-area graphene layers via DAS process at low temperatures. The details of synthesis and structural and optoelectronic characterization results will be presented elsewhere. We found that a precise control over the foil thickness, surface roughness and crystalline quality of the foils is critical to obtaining graphene films over large areas. We note that similar experiments carried out using single-crystal Ni foils do not yield graphene on either side of the foils, indicating that the GBs are necessary for low-temperature synthesis of graphene.

In summary, we have demonstrated transfer-free, large-area growth of graphene films via DAS method at close to room temperature. Our approach can, in principle, be used to grow device-ready graphene layers on any arbitrary substrate even in air and the resulting graphene layers exhibit controllable structural and optoelectronic properties by Ni GB engineering. This relatively simple method of synthesizing graphene films is potentially scalable and opens up new possibilities for a variety of electronic and optoelectronic applications.

Methods

Predeposition of Ni films on nonconducting substrates

All of our experiments were carried out using SiO2/Si, PMMA-coated SiO2/Si, poly-dimethylsiloxane and glass substrates (1–2 cm2 size). Polycrystalline Ni (poly-Ni) films with thickness of 100 nm are deposited using an electron-beam evaporator (operating pressure: ~5×10−6 Torr) with solid Ni (99.99% purity) as the source. The substrate temperature is set to 400 °C for SiO2/Si and room temperature (~25 °C) for plastics (PMMA and poly-dimethylsiloxane) and glass. Microstructure of the Ni thin films is determined using atomic force microscopy (Veeco Multimode V), scanning electron microscopy (SEM; FEI Quanta 200) and X-ray diffraction (Bruker D8 Advance) techniques.

As-deposited Ni thin films on SiO2/Si substrate have an average Ni grain size of ~100 nm (Supplementary Fig. S1a). To further control the grain size, crystallinity and morphology of poly-Ni films, the as-deposited samples were transferred to an ultrahigh vacuum chamber (<10−9 Torr) and annealed at temperatures as high as ~1,000 °C for times between 1 and 10 min in vacuum (~10−9 Torr) or in a H2 ambient (99.9999% purity) at pressures of 10−8–10−5 Torr. After annealing, we obtain Ni films with a predominantly 111-texture, with large crystalline grains of sizes around 5–20 μm and atomically flat terraces as shown in Supplementary Figures S1b and S1c. We find that H2 ambient is preferred to vacuum to obtain larger grains (Supplementary Fig. S1d). Using Raman spectroscopy (WiTec alpha 300R M-Raman), we rule out the presence of any crystalline C on the Ni films due to residual C segregation after annealing in a H2 ambient. In addition, we do not observe any crystalline C on SiO2 surfaces after etching away the metal films in an aqueous solution of FeCl3. In case of the Ni thin films deposited at room temperature on plastic and glass substrates, the average grain size is around 40–50 nm (Supplementary Fig. S2). Owing to the limited thermal stability of these materials, we did not anneal these samples.

Synthesis of graphene films by DAS process

As C sources, we used a paste composed of graphite powder (Aldrich, product 496596) dispersed in ethanol. The average size of graphite powder is ~40 μm. The paste was plastered to the Ni surface to make C–Ni/substrate diffusion couples and dried by heating the samples on a hot plate (<50 °C). Pressure (<1 MPa) is uniformly applied by mechanically clamping the C–Ni/substrate diffusion couple using a molybdenum holding stage. Then, the samples are sealed in a quartz tube and heated for 1–60 min while flowing inert Ar gas (1 standard l min−1) or air at temperatures between 25 and 600 °C. Following graphene growth, the samples are cleaned via sonication in deionized water, and the Ni films are removed by etching in an aqueous solution of FeCl3, leaving behind a graphene film on desired substrates. The etching time was found to be a function of the etchant concentration and type of the substrates. Typically, a 1 cm2 by 100-nm thick Ni film on a SiO2/Si substrate can be dissolved by 1 M FeCl3 solution within 30 min.

Fisher model

A highly idealized poly-Ni film matrix with square-shaped grains of side l, GB slabs of width δ and film thickness d is considered. Among all competing diffusion mechanisms, we only consider the lattice and GB diffusion quantities and ignore the dislocation quantity as insignificant dislocations threading normal to surface exist in face-centered cubic (FCC) Ni(111) film. Under these conditions, the number of atoms (ň) that flow per unit time is essentially equal to the product of the appropriate diffusivity (Di), concentration gradient (dc/dx) and transport area involved and the ratio of two fluxes can be estimated for FCC metals as ňGB/ňL=δ DGB/l DL=[(3×10−8)/l (cm)]exp(8.1TM/T)20. Assuming l=10 μm=10−3 cm and using TM of Ni=1726 K, we have ňGB/ňL=2.06×108 at 473 K, 2.15×103 at 773 K. Even if we consider the facts that real polycrystalline films contain various types and orientations of GBs and the lattice diffusion of C atoms in Ni film would occur by interstitial diffusion rather than substitutional diffusion used in the model, it is evident that lower temperatures greatly favour GB diffusion relative to lattice diffusion.

Density functional theory calculation

All calculations were performed using the VASP package based on the spin-polarized density functional theory32,33. We used a projector augmented wave potential34, and the generalized gradient approximation of Perdew and Wang35. All configurations were fully relaxed until the maximum residual forces were less than 0.01 eV/Å. The kinetic energy cutoff was 400 eV and the Monkhorst–Pack36 k-point grid was 5×5×1.

We calculated the stable adsorption site of a single C atom on a free-standing graphene sheet. The graphene model consisted of 32 C atoms with periodic boundary conditions along the in-plane directions. We found that a bridge-like site, where the added C atom sits on the centre of the bond between two neighbouring C atoms of graphene, is most favourable. To obtain the prefactor for the Arrhenius equation, the vibrational frequency of the added C atom on the adsorption site was calculated37. The adsorption energy and the vibrational frequency of the added C atom on the site were found to be 1.65 eV and 22.8 THz, respectively. In addition, the minimum energy pathway for the adatom diffusion was examined by the nudged elastic band method38. The additional C atoms in both initial and final configurations were located at the most energetically favourable sites, which were neighbours. Nine intermediate images, initially constructed by a linear interpolation between the initial and final configurations, were optimized along the diffusion pathway, which enables the determination of the minimum energy barrier. This minimum energy barrier was found to be 0.24 eV.

We then performed the same calculation of a single C atom diffusion on a free Ni(111) surface. The Ni thin film model consisted of 6 Ni(111) layers with 16 Ni atoms in each layer for a total of 96 Ni atoms. Periodic boundary conditions were applied along the in-plane directions, whereas the three bottom layers of the Ni film were held fixed during the diffusion process. We found that the C atom is most stable on the hexagonal close-packed (HCP) site, for which the adsorption energy is 7.01 eV, just 0.06 eV higher than on FCC site. In addition, the calculated energy barrier for the C atom diffusion on the Ni(111) surface is 0.49 eV.

To examine the diffusion of a single C atom along the graphene–Ni(111) interface, we obtained the stable configuration of a graphene sheet on a free Ni(111) surface. For this, eight C atoms for a graphene sheet and 24 Ni atoms for the Ni(111) surface were used. The graphene sheet was biaxially stretched using 1.22% tensile strain to remove the lattice mismatch between graphene and the Ni(111) surface. The equilibrium distance between the graphene sheet and the Ni(111) surface is 3.286 Å, and the interaction energy is 0.02 eV per each C atom. This is in good agreement with the earlier calculations27.

When we introduce an additional C atom at the interface between graphene and the Ni(111) surface, the energetically preferred position for the C atom is in the HCP site on the Ni(111) surface. The distance between the C atom and the Ni surface is 1.03 Å and the distance between the C atom and the graphene sheet is 2.62 Å, which indicates that the diffusion of a C atom along the interface will be more strongly influenced by the Ni surface than the graphene ML. The calculated diffusion barrier from the HCP site to the FCC site of the Ni(111) surface along the interface is found to be ~0.51 eV, which is slightly higher than that on a free Ni(111) surface. During the diffusion, there is no significant change in the distance between the C atom and the Ni surface. The hopping rate of a C atom can be found by the Arrhenius equation Γ=Γ0exp(−Eb/kT), which results in a room-temperature hopping rate of about 20,000 s−1 with an attempt frequency of Γ0=1.0×1013 Hz. In addition, the tracer diffusion coefficient can be expressed in terms of the hopping rate Γ and the mean square jump length <l2>: Dt=Γ<l2>/(2d), and is found to be ~200 nm2 s−1 using the lattice constant of Ni 3.52 ˚. If the chemical diffusion or the presence of graphene edges were considered, the diffusion coefficient would be higher than the calculated value of Dt.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Kwak, J. et al. Near room-temperature synthesis of transfer-free graphene films. Nat. Commun. 3:645 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1650 (2012).

References

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Two-dimensional gas of massless Dirac fermions in graphene. Nature 438, 197–200 (2005).

Zhang, Y., Tan, Y.- W., Stormer, H. L. & Kim, P. Experimental observation of the quantum Hall effect and Berry's phase in graphene. Nature 438, 201–204 (2005).

Zhou, S. Y. et al. Substrate-induced bandgap opening in epitaxial graphene. Nature Materials 6, 770–775 (2007).

Kwon, S.- Y. et al. Growth of semiconducting graphene on palladium. Nano Lett. 9, 3985–3990 (2009).

Balandin, A. A. et al. Superior thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene. Nano Lett. 8, 902–907 (2008).

Lee, C., Wei, X. D., Kysar, J. W. & Hone, J. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science 321, 385–388 (2008).

Bae, S. et al. Roll-to-roll production of 30-inch graphene films for transparent electrodes. Nature Nanotechnol. 5, 574–578 (2010).

Reina, A. et al. Large area, few-layer graphene films on arbitrary substrates by chemical vapor deposition. Nano Lett. 9, 30–35 (2009).

Kim, K. S. et al. Large-scale pattern growth of graphene films for stretchable transparent electrodes. Nature 457, 706–710 (2009).

Li, X. et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform graphene films on copper foils. Science 324, 1312–1314 (2009).

Sun, Z., Yan, Z., Beitler, E., Zhu, Y. & Tour, J. M. Growth of graphene from solid carbon sources. Nature 468, 549–552 (2010).

Yan, Z. et al. Growth of bilayer graphene on insulating substrates. ACS Nano 5, 8187–8192 (2011).

Peng, Z., Yan, Z., Sun, Z. & Tour, J. M. Direct growth of bilayer graphene on SiO2 substrates by carbon diffusion through nickel. ACS Nano 5, 8241–8247 (2011).

Shelton, J. C., Patil, H. R. & Blakely, J. M. Equilibrium segregation of carbon to a nickel(111) surface: a surface phase transition. Surf. Sci. 43, 493–520 (1974).

Isett, L. C. & Blakely, J. M. Segregation isosteres for carbon at the (100) surface of nickel. Surf. Sci. 58, 397–414 (1976).

Vang, R. T. et al. Controlling the catalytic bond-breaking selectivity of Ni surfaces by step blocking. Nature Materials 4, 160–162 (2005).

Tan, X. & Yang, G. W. Catalytic bond-breaking selectivity in the ethylene decomposition on Ni surfaces: kinetic Monte Carlo simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 4219–4225 (2008).

Fisher, J. C. Calculation of diffusion penetration curves for surface and grain boundary diffusion. J. Appl. Phys. 22, 74–77 (1951).

Balluffi, R. W. & Blakely, J. M. Special aspects of diffusion in thin films. Thin Solid Films 25, 363–392 (1975).

Schedin, F. et al. Detection of individual gas molecules absorbed on graphene. Nature Materials 6, 652–655 (2007).

Reeves, G. K. & Harrison, H. B. Obtaining the specific contact resistance from transmission line model measurements. IEEE Electron Dev. Lett. 3, 111–113 (1982).

Xia, F., Perebeinos, V., Lin, Y., Wu, Y. & Avouris, P. The origin and limits of metal-graphene junction resistance. Nature Nanotechnol. 6, 179–184 (2011).

Lamber, R., Jaeger, N. & Schulz-Ekloff, G. Electron microscopy study of the interaction of Ni, Pd, and Pt with carbon: I. Nickel catalyzed graphitization of amorphous carbon. Surf. Sci. 197, 402–414 (1988).

Berry, B. S. Diffusion of carbon in nickel. J. Appl. Phys. 44, 3792–3793 (1973).

Ajayan, P. M. & Yakobson, B. I. Graphene: pushing the boundaries. Nature Materials 10, 415–417 (2011).

Helveg, S. et al. Atomic-scale imaging of carbon nanofibre growth. Nature 427, 426–429 (2004).

Abild-Pederson, F. & Nrskov, J. K. Mechanism for catalytic carbon nanofiber growth studied by ab initio density functional theory calculations. Phys. Rev. B 73, 115419 (2006).

Geng, H.- Z. et al. Effect of acid treatment on carbon nanotube-based flexible transparent conducting films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 7758–7759 (2007).

Ferrari, A. C. & Robertson, J. Interpretation of Raman spectra of disordered and amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B 61, 14095–14107 (2000).

Nair, R. R. et al. Fine structure constant defines visual transparency of graphene. Science 320, 1308 (2008).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab-initio total energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B 46, 6671–6687 (1992).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Ala-Nissila, T., Frerrando, R. & Ying, S. C. Collective and single particle diffusion on surfaces. Adv. in Phys. 51, 949–1078 (2002).

Mills, G., Jonsson, H. & Schenter, G. K. Reversible work transition state theory: application to dissociative adsorption of hydrogen. Surf. Sci. 324, 305–337 (1995).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support from Research Fund of the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (Grants No. 1.080014.01, 1.110019.01) and from the Basic Science Research Program (Grants No. 2009-0074599, 2010-0009824, 2011-0005467, 2011-0013440) and from National Nuclear R&D Program (Grant No. 2011-0006387) and from World Class University Program (Grant No. R31-2008-000-10075-0) through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. SK gratefully acknowledges support from UCLA COR-FRG. This work has benefited from the use of the facilities at UNIST Central Research Facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-Y.K. planned and supervised the project; E.Y. and S.K. advised on the project; J.K., J.H.C., J.-K.C. and S.-Y.K. designed and performed experiments; S.-D.K. and Y.-W.K. made TEM samples and the structural measurements; J.K, H.G. and K.P. performed the electrical measurements; and S.-D.P. and S.Y.K. performed density functional theory calculations and the analyses; S.-Y.K., S.K., S.Y.K., K.P. and J.K. analysed data and wrote the manuscript; All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S9, Supplementary Methods, Supplementary References (PDF 935 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kwak, J., Chu, J., Choi, JK. et al. Near room-temperature synthesis of transfer-free graphene films. Nat Commun 3, 645 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1650

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1650

This article is cited by

-

Understanding the 2D-material and substrate interaction during epitaxial growth towards successful remote epitaxy: a review

Nano Convergence (2023)

-

Selective area multilayer graphene synthesis using resistive nanoheater probe

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Continuous epitaxy of single-crystal graphite films by isothermal carbon diffusion through nickel

Nature Nanotechnology (2022)

-

Bias-controlled plasmon switching in lithium-doped graphene on dielectric model Al2O3 substrate

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2020)

-

Synthesis of single-layer graphene film by chemical vapor deposition with molten gallium catalyst on silicon dioxide

Journal of Materials Science (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.