Abstract

Single-photon emitters have been considered for applications in quantum information processing, quantum cryptography and metrology. For the sake of integration and to provide an electron photon interface, it is of great interest to stimulate single-photon emission by electrical excitation as demonstrated for quantum dots. Because of low exciton binding energies, it has so far not been possible to detect sub-Poissonian photon statistics of electrically driven quantum dots at room temperature. However, organic molecules possess exciton binding energies on the order of 1 eV, thereby facilitating the development of an electrically driven single-photon source at room temperature in a solid-state matrix. Here we demonstrate electroluminescence of single, electrically driven molecules at room temperature. By careful choice of the molecular emitter, as well as fabrication of a specially designed organic light-emitting diode structure, we were able to achieve stable single-molecule emission and detect sub-Poissonian photon statistics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Single-photon emission has been observed from a variety of quantum emitters including semiconductor quantum dots1,2,3,4, molecules5,6,7,8, atoms9, ions10 and colour centres in diamond11,12,13. Semiconductor quantum dots, in particular from III/V materials, prove to be especially fascinating tools for electrically driven single-photon generation14. However, a major drawback for these structures so far is the necessity of cryogenic temperatures because of low exciton binding energies15.

In contrast to semiconductor quantum dots, single organic molecules embedded in molecular crystals or polymers offer adequate exciton binding energies for room temperature operation16. In this context, it is particularly important to choose an appropriate molecular emitter. In molecular photoexcitation experiments one usually chooses molecules with a high fluorescence quantum yield, that is, low intersystem crossing and hence triplet-state population. This is in sharp contrast to electroluminescence in which the underlying electron-hole spin recombination statistics results in a triplet-state excitation probability of 75% and a singlet-state excitation probability of 25%17. Therefore, the use of fluorescent emitters such as terrylene or dibenzoterrylene emitting from a singlet state is unfavourable17,18. Instead, to efficiently convert electrical excitation energy into photon emission it is necessary to use a molecule, which is able to trap electron-hole pairs in its T1 triplet state and to emit photons by phosphorescence. Additional requirements include almost 100% internal quantum efficiencies in solid-state matrices19 and a short triplet-state lifetime. Examples of such molecular systems include organometallic complexes with a centred heavy metal ion20 possessing high intersystem crossing probabilities. For such molecular complexes, optical excited triplet-state photon antibunching on microsecond time scales was achieved using single Ru(dpp)3 molecules7. In terms of electrical excitation, recent progress was made by using Ir(btp)2acac molecules in organic light-emitting diode (OLED) structures, thereby, indicating single-molecule sensitivity and emissive features in electroluminescence21. However, owing to limited device stability and low emission rates, electrically excited photon antibunching from a single organic molecule was not observed so far.

In this work, single Ir(piq)3 (tris(1-phenylisoquinoline)iridium) molecules22 were used as emitters inside wide bandgap poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) and poly(9-vinylcarbazole) (PVK):2-(4-tert-butylphenyl)-5-(4-biphenylyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (PBD) polymers. Iridium-based emitters are known for their short triplet-state lifetimes compared with other organometallic complexes20. Major advantages of Ir(piq)3 compared with iridium complexes of the Ir(thpy)3 type, which emits through a ligand-centred (3π−π*) excited state, include high phosphorescent quantum yields while emitting at long wavelengths around 620 nm. Emission in Ir(piq)3 is reported to be caused by excitation of a metal-to-ligand charge transfer state with a lifetime of 1.1 μs, thereby increasing radiative emission and phosphorescent quantum yield20.

Results

Optical excitation of single phosphorescent molecules

To characterize the so far unknown photophysical properties of Ir(piq)3 molecules, single molecules in PMMA films were studied optically using 488 nm laser excitation (Fig. 1a). Because of emissive triplet-state lifetimes on the microsecond time scale, the excitation power density was kept at comparatively23 low intensities (2 kW cm−2). Higher excitation powers increase the probability of molecular photo-bleaching by photo-assisted excitation from the triplet ground state T1 to higher excited states24. At 2 kW cm−2, the bleaching time of Ir(piq)3 varied between a few seconds up to a couple of minutes.

(a) Confocal microscopy scan of single Ir(piq)3 molecules diluted in PMMA using a 585-nm longpass filter in the detection path. The colour bar marks the photoluminescence intensity measured as detected photons per second (cps). At 2 kW cm−2 excitation intensity, single Ir(piq)3 molecules showed an emission rate of 10 kcps. Brighter emission sites are related to fluorescent impurities in the host polymer. (b) Spectral characteristics of single Ir(piq)3 molecules in PMMA. The emission shows a maximum intensity at 613 nm for the respective molecule. (c) Triplet-state photon antibunching recorded on an optically driven single Ir(piq)3 molecule in PMMA at an emission intensity of 10 kcps. The single exponential fit, which is based on the occupation probability of the molecule's emissive triplet state after photon emission is highlighted by a red line in the experimental data, corresponding to a triplet-state lifetime of 1.1 μs. Thereby, values of the second-order correlation function g2(τ) below 0.5 indicate emission from a single molecule. (d) Intensity trace during single molecule photon correlation measurement displayed in (c). Emission lasted for about 90 s before single-step photobleaching. (e) Dependence of emissive k31 rate on the excitation power. Because of photo-assisted de-excitation, the k31 rate increases linearly with higher laser intensities marked by the red fit. (f) Dependency of the photoluminescence signal of a single Ir(piq)3 molecule on the excitation intensity. The red line is a fit, which was derived from the steady state solution of the molecule's rate equations. The rates between contributing molecular states S0, S1 and T1 are depicted by blue arrows in the inset, respectively. Since in the case of Ir(piq)3 molecules k23 is orders of magnitude larger than k21 and k31, the emission rate only depends on k31 for a respective excitation intensity. Saturated emission thereby originates from the finite lifetime of the molecule's triplet state showing full saturation at 69,500 cps for a single Ir(piq)3 molecule in detection and a saturation intensity of 7 μW.

Spectral investigations on isolated molecules reveal an emission maximum at 613 nm (Fig. 1b), which fits to reported data obtained by ensemble measurements on saturated toluene solutions20. To gain deeper insight into the photophysics and photon emission characteristics, the intensity autocorrelation function g2(τ) of emitted photons was recorded (Fig. 1c). As can be seen, g2(τ) adopts values smaller than 0.5 (sub-Poissonian) for shorter time scales, indicating the emission from a single phosphorescent molecule. From the slope, an emissive triplet lifetime of 1.1 μs was determined. During acquisition of the correlation function, molecular photon emission added up to 12 kcps for 90 s followed by an abrupt bleaching of the Ir(piq)3 molecule in a single time step (Fig. 1d). Single-step photobleaching is a known phenomenon when dealing with single-dye molecules, which are exposed to constant laser excitation. By measuring the correlation function for different excitation intensities, the k31 rate dependence on the laser excitation intensity can be determined (Fig. 1e). For higher excitation intensities, k31 increases due to photo-assisted de-excitation of the respective emissive state. By approximation to zero laser intensity an intrinsic lifetime of the emissive triplet state of 1.3 μs can be deduced. By measuring the intensity dependence of the emission of a single Ir(piq)3 molecule (Fig. 1f), a maximum detected saturated emission intensity of 69,500 counts per second (cps) was recorded. For an emissive lifetime in the order of 1 μs and 100% emission quantum yield, a maximum count rate of 1×106 cps can be expected (see Methods). With a saturated emission intensity of 69,500 cps, 7% of the expected photons are detected that corresponds to the independently determined detection efficiency of the confocal setup (~5%). This result indicates that Ir(piq)3 possess no intrinsic non-radiative decay channels, as observed, for example, for the red emitting complex Btp2Ir(acac)19 and thereby almost 100% efficiency for triplet emission.

Electrical excitation of single phosphorescent molecules

To electrically excite single phosphorescent molecules and to obtain detectable emission rates, bipolar current densities of at least 1 mA cm−2 are required for charge carrier capture cross-sections in the order of 20 nm (ref. 25) in radius and triplet-state emissive lifetimes of 1 μs. Besides adequate charge-carrier densities, it is essential that the current density meets certain stability requirements. This not only concerns overall temporal emission stability of the OLED but also spatially stable and homogenous current densities in the order of the molecular capture cross-section.

As the energy of charge carriers and excitons, respectively, cannot be tuned as similar to laser excitation wavelengths, another crucial aspect is background emission and spectral properties of the dye, which needs to be separable from host emission characteristics.

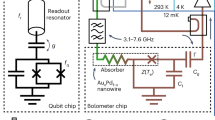

To meet these requirements, we have optimized spectral emission properties by using a phosphorescent dye molecule emitting in the red spectral range above 600 nm while utilizing a host polymer, which emits in the blue spectral range. To meet the stability requirements and achieve adequate charge-carrier densities low work function barium metal suitable for electron injection was used as cathode (see Fig. 2). Finally, to avoid OLED degradation mechanisms26,27 and thereby prevent spatial and temporal intensity fluctuations, all manufacturing steps took place under inert conditions thereby minimizing contaminations of oxygen and humidity. By subsequently encapsulating the OLED it was ensured that no oxygen or humidity was able to diffuse into the emission layer under operation.

Schematic representation of the OLED layer stack used for electrical excitation of single phosphorescent Ir(piq)3 molecules. The sample comprises of a combination of 100 nm of aluminium and 1 nm of barium for electron injection, whereas hole injection is provided by an ITO anode of 200 nm thickness covered with 20 nm of PEDOT:PSS. The doped polymer film of 60 nm thickness is situated between the contacts and detection of single-molecule photon emission is performed through the transparent PEDOT:PSS/ITO contact. The encapsulation by a top glass plate is not shown in the image. OLEDs used in this work consist of 11 individual contacts of different sizes ranging from diameters of 10 μm up to 2 mm. Depicted in the inset is the chemical structure of Ir(piq)3 molecule used as a phosphorescent dopant. The chemical complex consists of a central Iridium atom and three 1-phenylisoquinoline ligands.

Isolated phosphorescent Ir(piq)3 molecules were dispersed in the opto-electrically active PVK:PBD layer of the OLED structure. Peak emission of PVK:PBD is located around 440 nm (ref. 28) thereby energetically positioning Ir(piq)3 within the PVK:PBD bandgap20 and providing the possibility of spectrally separating the dopants from the polymer. In Figure 3a, the current density and the overall emission intensity of the OLED is plotted in dependence of the applied voltage. Onset of photon emission occurred above 5 V, which can be related to injection barriers at the respective contact interface29. Above this threshold, electron hole recombination takes place either on the polymer or dopant molecules reaching a maximum current density of up to 200 mA cm−2. A spatially resolved image of the electroluminescent layer (Fig. 3b) together with a linear scan along the dashed line (Fig. 3c) reveals electroluminescence from individual spots at an applied voltage of 12 V. Despite a large overall background due to recombination in the polymer matrix and near the contacts on the order of 17 kcps, isolated emission spots could be observed at an intensity of up to 6 kcps above background. Spectral investigations reveal (Fig. 3d) that the electroluminescence signal consists of contributions from the polymer and from the dispersed dopant molecules, the latter showing a peak in intensity at roughly 613 nm, which can only be observed on the isolated emission spots. Background-corrected electroluminescence emission spectra are identical to the PL signal of single Ir(piq)3 molecules (Fig. 3e) and lead us to conclude that the emission stems from electrical recombination dynamics (Fig. 3f) on Ir(piq)3 molecules.

(a) Voltage-dependent current density and integrated emission intensity of a PVK:PBD OLED containing 2×10−7 wt% Ir(piq)3 concentration. (b) Confocal microscopy scan of the OLED at 12 V using a 585-nm longpass filter in detection. Isolated emission sites can be related to single Ir(piq)3 molecules. The colour bar marks the electroluminescence intensity measured as detected photons per second. (c) Background-corrected line scan along the dashed line in (b). (d) The black curve shows spectral features measured on the isolated emission site of maximum intensity along the vertical scan in (b). Comparing these spectral features with spectra (red line) recorded on the background (outside spots of enhanced electroluminescence emission), it can be concluded that isolated emission sites are related to electrical excited Ir(piq)3 molecules (613 nm), whereas the homogenously distributed background electroluminescence can be attributed to polymeric background emission. (e) Comparison of optically excited emission spectra of single Ir(piq)3 molecules (red line) with the background corrected emission spectra of electrically driven Ir(piq)3 molecules (black line), obtained by the difference of the two data sets in (d), corroborates their identical origin. (f) Electrical excitation scheme of a single-molecular emitter in a semiconducting polymeric matrix with conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB). By voltage application, electrons are injected from the cathode into the CB and holes from the anode into the VB. Dopants acting as recombination sites thereby generating excitons either as charged trap for free carriers or as neutral trap for electron-hole pairs. Because of the fermionic nature of electrons and holes, the resulting exciton can be of either spin 0 or spin 1. As each spin projection quantum number ms has the same probability to be populated, the chance to excite the singlet state (S=0) amounts to 25% and to 75% for the triplet state (S=1). In the diagram, values for the intra-molecular rates and the phosphorescent emission wavelength of a single Ir(piq)3 molecule are listed.

To prove single-molecule electroluminescence30, population kinetics were analysed by measuring photon correlation statistics. Therefore, a constant voltage of 12 V was applied and an isolated emission site was selected. Photon correlation measurements on these emission spots showed electrically driven sub-Poissonian photon statistics with a phosphorescence lifetime constant of 1.1 μs originating from an electrically excited single Ir(piq)3 molecule (Fig. 4a). Because of uncorrelated polymeric background emission the contrast of the correlation function in raw data is low but can be corrected for background contribution31 (see Methods). As depicted in Figure 4b, background-corrected photon statistics show a second-order correlation function, which adopts values smaller than 0.5, proving that emission above background resulted from a single electrically excited Ir(piq)3 molecule.

(a) Electrically driven photon antibunching measured on an isolated emission spot at an applied external voltage of 12 V and a current density of 3 mA cm−2. During measurement, homogenously distributed polymeric background emission summed up to 17 kcps compared with 6 kcps resulting from the single phosphorescent Ir(piq)3 molecule. Because of background photon emission, the contrast of the correlation function is reduced. The red line represents a single exponential fit to the experimental data showing a decay time of 1.1 μs. (b) Performing a background correction of the correlation function displayed in (a), it can be shown that g2(τ) adopts values smaller than 0.5 thereby proving evidence that the electrically excited emission originates from a single phosphorescent Ir(piq)3 molecule.

By comparing lifetime distributions for a couple of different electrically excited single Ir(piq)3 molecules using the same applied voltage of 12 V, a spread between 1.0 and 1.4 μs was observed. These values match lifetime distributions measured on photo-excited single Ir(piq)3 molecules as discussed in the Methods and can be attributed to variations in the local environment, induced, for example, by mechanical stress, of each individual molecule. Observing identical lifetimes and emission spectra in electro- and photoluminescence of single Ir(piq)3 molecules indicates that the same molecular states are involved in both emission processes.

Discussion

The basic excitation mechanism of single dopant molecules by charge carriers is described by Langevin recombination25. In this model, a charge carrier gets locally trapped, attracting charge carriers of opposite polarity once they pass within a certain capture radius of the dopant molecule. The capture radius in this model is defined as the distance between molecule and charge carrier at which coulomb attraction is equal to the thermal energy of the charge carrier. The trapping rate n, which is the sum of electron and hole trapping, is proportional to the current density j at the position of the dopant molecule,

For organic polymers with a dielectric constant of 3.4, the capture radius rc is calculated to be rc=17 nm. This value allows calculation of the electroluminescence intensity for a certain applied current density j. As two charge carriers are required for an excitation process we therefore assumed that the trapping rate n to correspond to half of the excitation rate. It is important to note that a linear relationship between current density and emission rate is only given at low excitation powers below saturation (js=25 mA cm−2). According to Figure 3a, at an applied voltage of 12 V, a current density of 3 mA cm−2 was passing through the OLED yielding an excitation rate of 8.5×104 s−1. With a detection efficiency of the confocal microscope setup of 5%, a count rate of 4,300 cps would be expected that agrees with the detected intensity of single Ir(piq)3 molecules (see Fig. 3c).

Regarding the stability of the electroluminescence signal, it is possible to detect single molecule emission up to a couple of minutes. After that, because of well-known intrinsic charging effects of this type of polymer32,33, the charge carrier recombination zone drifts away from the dopant molecule under investigation. Either by discharging or applying a reverse bias in the opposite direction the recombination zone can be shifted backwards again.

In conclusion, we demonstrated electrically and optically excited room temperature photon antibunching of the phosphorescent organometallic dye Ir(piq)3. This method allows the unique possibility to directly observe single electrically driven phosphorescent molecules in a solid-state device thereby allowing further investigations of emission mechanisms, quantum yields and nanoscale current dynamics in working OLED devices. By further improving device performance and signal to noise ratio, electrically driven single photon generation limited only by the lifetime achieved in commercial OLED devices is expected. Such structures can be easily integrated into existing quantum optical circuits. Furthermore, single phosphorescent molecules possess a magnetic moment of the excited triplet state, which can be used as a magnetic field sensor either by optical or electrical single-molecule excitation.

Methods

Sample fabrication

Two kinds of polymers were studied as host matrices for optical excitation of single tris(1-phenylisoquinoline)iridium (Ir(piq)3) molecules. First, PMMA, which possessed a good degree of purity but is not applicable in OLEDs and second PVK, which in contrast can be used as emission layer but showed increased impurity concentrations thereby complicating initial characterization steps. PMMA and PVK were dissolved in toluene at concentrations of 40 and 18 mg ml−1, respectively. Sublimed Ir(piq)3 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and was used as received. To observe single molecules using room temperature confocal microscopy, Ir(piq)3 molecules were diluted in the PMMA and PVK solutions at low concentrations of 15 ng ml−1. At these low concentrations, self-quenching phenomena between neighbouring phosphorescent molecules can be excluded. By performing spin coating at 500 r.p.m., these solutions yield thicknesses of 110 nm for PMMA and 70 nm for PVK, which were experimentally determined by X-ray reflectivity measurements.

To increase stability and minimize the probability of photobleaching, spin coating was performed under inert conditions in a nitrogen gas atmosphere34. For further investigations, the thin polymer films were encapsulated in situ by a glass plate thus avoiding diffusion of oxygen into the polymer.

For electrical excitation Ir(piq)3 was diluted at 15 ng ml−1 in a toluene solution of 18 mg ml−1 PVK and 6 mg ml−1 PBD. The latter was required to increase electron conduction of the polymer film. The OLEDs consisted of a glass substrate (160 μm)/ITO (200 nm)/PEDOT:PSS (20 nm)/Ir(piq)3 doped PVK:PBD (60 nm)/Ba (1 nm)/Al (100 nm) layer stack as depicted in Figure 2. Before ITO sputtering, the glass substrates (50×50 mm) were cleaned using various kinds of solvents. At first a thin layer of PEDOT:PSS was spin coated on the ITO and baked at 120 °C for 15 min to remove residual water contents and to provide a defined work function before deposition of the PVK:PBD layer. Afterwards, all manufacturing steps took place in a glove box to avoid contaminations by humidity and oxygen. Ir(piq)3-doped PVK:PBD of 60 nm thickness was subsequently spin coated and post-annealed at 100 °C for 1 min. Afterwards, the structure was transferred in situ to a metal evaporation system to thermally evaporate the top-contact of barium and aluminium. Finally, the device was encapsulated by a glass plate to allow for operation under ambient conditions.

Experimental setup

The polymer films were optically investigated by a home-built confocal microscope using an excitation wavelength of 488 nm from an argon ion laser (Coherent Innova 310). The beam was focused by an oil immersion objective (Olympus ×60, NA=1.49) onto the sample, which was mounted on a 3D piezo scanner (P517, Physik Instrumente) with a scanning range of 200×200×20 μm3. Photoluminescence light was collected through the same objective and was detected by avalanche photodiodes after passing through a 585-nm longpass filter to block the excitation light from the sample. To obtain information about photon statistics, the setup allowed for simultaneous fluorescence correlation spectroscopy measurements recorded by a hardware correlator (ALV-5000).

Photon statistics and saturation behaviour

In Figure 1c the second-order correlation function of an optically excited single phosphorescent Ir(piq)3 molecule is plotted in dependence of time. On longer time scales, no photon bunching in the coincidence histogram can be detected, which is direct evidence that no additional dark state is populated within the optical cycle. From the slope of the correlation function, the lifetime of the emitting triplet state can be deduced by fitting to an exponential decay. The molecule detected in Figure 1c possessed a lifetime of 1.1 μs, which fits to the reported data on ensemble measurements of Ir(piq)3 molecules. However, in ensemble measurements it is not possible to obtain information about lifetime distributions. By measuring the correlation function for different molecules we observed lifetimes of Ir(piq)3 in PMMA between 0.82 and 1.55 μs. This discrepancy can be explained by slight variations in the local environment of different single molecules induced for example by mechanical strain.

To theoretically describe emission saturation (Fig. 1f), the Ir(piq)3 molecule can be described as a three-level system consisting of a singlet ground state S0, an S1 excited state and a triplet ground state T1. Because of high intersystem crossing probabilities, the transition rate from the excited singlet state S1 to the triplet ground state T1, k23, is in the order of 1013 s−1. As k21 is several orders of magnitude smaller than k23, the probability of photon emission by fluorescence can be neglected. Solving the steady-state solution of the rate equations under this assumption, it is possible to determine the emission intensity R in dependence of the excitation power for a phosphorescent emitter:

In this case k12=σI is proportional to the excitation intensity I and the absorption cross-section of the molecule σ. ϕ is the detection efficiency of emitted photons and τ is the lifetime of the triplet ground state T1. As can be seen, the emission rates of efficient single phosphorescent dye molecules only depend on the excitation rate k12 and the lifetime τ of the triplet state. Thereby, the maximum emission intensity is solely limited by the triplet state lifetime τ .

In Figure 1f the theoretical fit, which is marked by a red line, is compared with the experimental data yielding a cross-section of 2×10−17 cm2 for a single phosphorescent Ir(piq)3 molecule, which is comparable to fluorescent molecules and is in agreement with the behaviour of the intensity dependence of k31 (Fig. 1e). The reason for emission saturation of a single phosphorescent dye at optical excitation is the lifetime of the emitting triplet state. In our experiments the fully saturated emission rate R∞ yields 69,500 cps, whereas the laser power IS at the beginning of saturation was determined to be 7 μW.

Background correction of the correlation function

Because of uncorrelated background photon emission originating from charge carrier recombination on the polymer and near contact interfaces, the contrast of the electrically induced photon antibunching is reduced (Fig. 4a). The relationship between background-corrected and -uncorrected correlation functions is established by Brouri et al.31:

where ρ=S/(S+B), in which S equals the emission from a single Ir(piq)3 molecule and B equals the emission from the background. Figure 4a presents raw data, which was already normalized to that of a Poissonian light source during the measurement time and is the equivalent to CN(t). By using a value of ρ=0.26, which equals a molecular emission of 6 kcps and a background emission of 17 kcps, Figure 4a was background corrected and is displayed in Figure 4b.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Nothaft, M. et al. Electrically driven photon antibunching from a single molecule at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 3:628 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1637 (2012).

References

Lounis, B., Bechtel, H. A., Gerion, D., Alvivisatos, P. & Moerner, W. E. Photon antibunching in single CdSe/ZnS quantum dot fluorescence. Chem. Phys. Lett. 329, 399–404 (2000).

Michler, P. et al. A quantum dot single-photon turnstile device. Science 290, 2282–2285 (2000).

Salter, C. L. et al. An entangled-light-emitting diode. Nature 465, 594–597 (2010).

Strauf, S. et al. High-frequency single-photon source with polarization control. Nat. Photon. 1, 704–708 (2007).

Basché, T., Moerner, W. E., Orrit, M. & Talon, H. Photon antibunching in the fluorescence of a single dye molecule trapped in a solid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 1516–1519 (1992).

Fleury, L., Segura, J., Zumofen, G., Hecht, B. & Wild, U. Nonclassical photon statistics in single-molecule fluorescence at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 1148–1151 (2000).

Hu, D. & Lu, H. P. Single-molecule triplet-state photon antibunching at room temperature. Phys. Chem. B 109, 9861–9864 (2005).

Lounis, B. & Moerner, W. E. Single photons on demand from a single molecule at room temperature. Nature 407, 491–493 (2000).

Kuhn, A., Hennrich, M. & Rempe, G. Deterministic single-photon source for distributed quantum networking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 067901 (2002).

Keller, M., Lange, B., Hayasaka, K., Lange, W. & Walther, H. Continous generation of single photons with controlled waveform in an ion-trap cavity system. Nature 431, 1075–1078 (2004).

Gruber, A. et al. Scanning confocal optical microscopy and magnetic resonance on single defect centers. Science 276, 2012–2014 (1997).

Childress, L. et al. Coherent dynamics of coupled electron and nuclear spin qubits in diamond. Science 314, 281–285 (2006).

Jelezko, F. et al. Observation of coherent oscillation of a single nuclear spin and realization of a two-qubit conditional quantum gate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 130501 (2004).

Yuan, Z. et al. Electrically driven single-photon source. Science 295, 102–105 (2002).

Meulenberg, R. W. et al. Determination of the exciton binding energy in CdSe quantum dots. ACS Nano 3, 325–330 (2009).

Knupfer, M. Exciton binding energies in organic semiconductors. Appl. Phys. A 77, 623–626 (2003).

Yersin, H. Triplet emitters for oled applications. Mechanisms of exciton trapping and control of emission properties. Top. Curr. Chem. 241, 1–26 (2004).

Nothaft, M. et al. Optical sensing of current dynamics in organic light-emitting devices at the nanometer scale. ChemPhysChem 12, 2590–2595 (2011).

Kawamura, Y. et al. 100% Phosphorescence quantum efficiency of Ir(III) complexes in organic semiconductor films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 071104 (2005).

Yersin, H. Highly Efficient OLEDs with Phosphorescent Materials (Wiley-VCH 2008).

Sekiguchi, Y., Habuchi, S. & Vacha, M. Single-molecule electroluminescence of a phosphorescent organometallic complex. Chem. Phys. Chem. 10, 1195–1198 (2009).

Hedley, G. J., Ruseckas, A. & Samuel, I. D. W. Ultrafast intersystem crossing in a red phosphorescent iridium complex. Phys. Chem. A 113, 2–4 (2009).

Kulzer, F., Koberling, F., Christ, T., Mews, A. & Basché, T. Terrylene in p-terphenyl: single-molecule experiments at room temperature. Chem. Phys. 247, 23–34 (1999).

Deschenes, L. A. & Vanden Bout, D. A. Single molecule photobleaching: increasing photon yield and survival time through suppression of two-step photolysis. Chem. Phys. Lett. 365, 387–395 (2002).

Pope, M. & Swenberg, C. Electronic Processes in Organic Crystals and Polymers (Oxford University Press, 1999).

Burrows, P. E. et al. Reliability and degradation of organic light emitting devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 65, 2922–2924 (1994).

Sheats, J. R. et al. Organic electroluminescent devices. Science 273, 884–888 (1996).

Wu, C. C. et al. Efficient organic electroluminescent devices using single-layer doped polymer thin films with bipolar carrier transport abilities. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 44, 1269–1281 (1997).

Koch, N. Organic electronic devices and their functional interfaces. ChemPhysChem 8, 1438–1455 (2007).

Lupton, J. M. Single-molecule spectroscopy for plastic electronics: materials analysis from the bottom-up. Adv. Mater. 22, 1689–1721 (2010).

Brouri, R., Beveratos, A., Poizat, J. P. & Grangier, P. Photon antibunching in the fluorescence of individual color centers in diamond. Opt. Lett. 25, 1294–1296 (2000).

Yang, X. H. & Neher, D. Polymer eletrophosphorescence devices with high power conversion efficiencies. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 2476–2478 (2004).

Cai, M. et al. High-efficiency solution-processed small molecule electrophosphorescent organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 23, 3590–3596 (2011).

Lill, Y. & Hecht, B. Single dye molecules in an oxygen-depleted environment as photostable organic triggered single-photon sources. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 1665–1667 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support by the DFG within the research group programme on positioning of single nanostructures—single quantum devices (FOR 730).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.J., N.F., J.P. and J.W. designed the experiment. M.N. conducted the experiments. S.H. prepared the sample. M.N., J.P. and J.W. wrote the paper. All authors contributed through scientific discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nothaft, M., Höhla, S., Jelezko, F. et al. Electrically driven photon antibunching from a single molecule at room temperature. Nat Commun 3, 628 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1637

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1637

This article is cited by

-

Recent advances in room temperature single-photon emitters

Quantum Information Processing (2023)

-

Investigation of electronic excited states in single-molecule junctions

Nano Research (2022)

-

Single-photon emission from isolated monolayer islands of InGaN

Light: Science & Applications (2020)

-

Genesis, challenges and opportunities for colloidal lead halide perovskite nanocrystals

Nature Materials (2018)

-

High-contrast switching and high-efficiency extracting for spontaneous emission based on tunable gap surface plasmon

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.