Abstract

Inward rectifier potassium (Kir) channels are physiologically regulated by a wide range of ligands that all act on a common gate, although structural details of gating are unclear. Here we show, using small molecule fluorescent probes attached to introduced cysteines, the molecular motions associated with gating of KirBac1.1 channels. The accessibility of the probes indicates a major barrier to fluorophore entry to the inner cavity. Changes in fluorescence resonance energy transfer between fluorophores, attached to KirBac1.1 tetramers, show that phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate-induced closure involves tilting and rotational motions of secondary structural elements of the cytoplasmic domain that couple ligand binding to a narrowing of the cytoplasmic vestibule. The observed ligand-dependent conformational changes in KirBac1.1 provide a general model for ligand-induced Kir channel gating at the molecular level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inward rectifier potassium (Kir) channels are encoded by members of a major structural K channel family. Each subunit contains a unique cytoplasmic 'Kir' domain, formed by the amino- and extensive carboxy- termini, through which these channels are physiologically regulated by a wide range of ligands1,2. For example, Kir1.x is gated by intracellular pH (refs 3, 4), and Kir3.x (GIRKs) is opened by Gβγ subunits5,6, whereas Kir6.x (KATP) is closed by ATP7. All eukaryotic Kir channels share a common activatory ligand, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), which again acts through binding to the Kir domain8,9,10. Despite the physiological significance of ligand-gating, the molecular motions associated with ligand-induced gating remain unclear.

A class of prokaryotic Kir channel homologues, referred to as KirBac channels, have also been identified and characterized11,12,13,14, and crystal structures of full-length prokaryotic KirBac1.1 and eukaryotic Kir2.2 were first obtained in 2003 and 2009, respectively15,16. Kir channel crystal structures share high similarity to other K channel structures in the transmembrane regions, but are unique within the 'Kir' cytoplasmic domain15,16,17. Both eukaryotic Kir and KirBac channels therefore contain the appropriate 'Kir' domain for ligand-gating, although, in striking contrast to all eukaryotic Kir channels, KirBac1.1 is inhibited by PIP2 (refs 13, 18, 19), potentially because of key structural differences in the linkers between the Kir domain and the transmembrane domains8,19,20. There is accumulating evidence that gating in many K channels, including inward rectifiers, requires a bending/rotating motion of the pore-forming transmembrane α-helices to remove the bundle crossing gate21,22,23,24,25,26. For KcsA, neutralization of negatively charged residues at acidic pH enhances the repulsion contributed by positively charged residues clustered at the bundle crossing, thereby stabilizing the channel in the open state27,28,29. Molecular dynamics simulations, mass spectrometric measurements, AFM techniques and GFP-based FRET approaches have also provided data consistent with the interpretation that ligand-dependent opening of Kir channels involves opening of the bundle crossing gate and rearrangement of the cytosolic domain24,30,31,32. Irrespective of where the ligand-operated gate is actually located, such studies have provided no information on the molecular motions of the Kir domain that underlie the gating, that is, the molecular motions that are induced by ligand binding.

Recently, Clarke et al.33 presented 11 KirBac3.1 crystal structures that demonstrate differences in ion occupancies within the selectivity filter, and differences within the cytosolic domain. We proposed a gating mechanism at the selectivity filter mediated by interaction between the cytoplasmic domain and the slide helix, although none of these structures actually demonstrate an opening of the bundle crossing that could support conduction, and it is not clear how the structural variants that are observed actually relate to gating states34.

In the present work, we set out to examine gating motions within the KirBac1.1 channel protein that are definitively associated with ligand-gating, using PIP2 as a ligand to drive channel closure. The data demonstrate specific motions of Kir domain β-sheets that result in narrowing of the cytoplasmic pore during PIP2-induced closure.

Results

A major pore barrier at the bundle crossing

Wild-type KirBac1.1 contains no cysteines (Supplementary Fig. S1) and thus provides a suitable model system for the introduction of cysteines that can be labelled with fluorescent tags. We first tested accessibility of substituted cysteines at different positions within the channel pore to Alexa Fluor 488 C5 maleimide (AF-488). The results (Fig. 1a,c) show that all substituted cysteines up to and including residue 150C are rapidly modified, indicating no barrier to the relatively bulky AF-488. There is only very slow modification of residues A147C and F149C, and no modification by AF-488 of cysteine residues that are actually within the inner cavity (A109C, T110C, I138C, T142C, G143C, V145C and F146C). In addition to a major restriction at the bundle crossing (immediately above residue 150), eukaryotic Kir crystal structures have revealed a secondary constriction at the so-called G-loop (that includes residue 264, Fig. 1e), located just below the bundle crossing35,36,37. Our results indicate a major restriction at the bundle crossing, whereas the G-loop provides no detectable barrier to access of AF-488.

Time course (a, b) and 10 min time-point data (c, d, boxed in a, b) of Alexa-Fluor 488 C5 maleimide incorporation (F, a.u.) into cysteine-substituted KirBac1.1 mutants in the presence or absence of 10 μg ml−1 diC8–PIP2 (mean±s.e., n=3 in each case; error bars are smaller than symbol in most cases) (e) Ribbon diagram indicating accessibility of AF-488 to substituted cysteine residues. Alpha carbons of tested residues in this and subsequent figures are highlighted by spheres, with inaccessible residues coloured red, limited accessible (147 and 149) purple, and highly accessible blue.

As discussed above, PIP2 has an inhibitory effect on KirBac1.1 channel activity13,19, and modification rates of pore-lining cysteines within the cytoplasmic vestibule all dropped ~15% in the presence of 10 μg ml−1 diC8–PIP2 (Fig. 1b,d). The modification rate was even slower (~30%) at residue 180C that is located on the outer wall of the cytosolic domain. This residue is close to PIP2-binding sites recently identified in Kir2.2 and Kir3.2 by crystallography8,35, and, potentially, the reduced accessibility reflects shielding of 180C as a consequence of diC8–PIP2 binding.

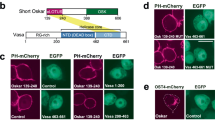

KirBac1.1 cysteine mutants are functional and PIP2 sensitive

Random labelling of mutant proteins with cysteine-reactive FRET donor/acceptor mixtures allows us to measure the gating-associated motions of labelled cysteines induced by PIP2. In the present work, cysteine residues were introduced at 21 different positions throughout the KirBac1.1 cytoplasmic domain (Supplementary Fig. S1) and randomly labelled by EDANS C2 maleimide/DABCYL-plus C2 maleimide (E/D, R0=33 Å) or Alexa-Fluor-546 C5 maleimide/DABCYL-plus C2 maleimide (A/D, R0=29 Å). We previously showed that wild-type KirBac1.1 in phosphatidylethanolamine (POPE)/phosphatidylglycerol (POPG) (3:1) liposomes has high intrinsic open probability, but channel open probability is dramatically decreased by low levels of PIP2 (refs 13, 19). We examined the channel activity, and PIP2-sensitivity, of fluorophore-labelled KirBac1.1 cysteine mutants using a rubidium flux assay. Most fluorophore-labelled mutants are functional and remain sensitive to PIP2 inhibition (Fig. 2). Four mutants, including 177-AD, 186-AD, 228-AD and 306-ED were non-functional. Among these, 177-AD is apparently a consequence of the labelling, because 177-ED is still functional and PIP2 sensitive. Residue 228 is located in the middle of the major β-sheet (βI, see below), whereas 186 is located at a subunit interface, and 306 is located at the extreme C-terminal end of the protein, in a small β-sheet region that is conserved among Kir channel members (Supplementary Fig. S1). Structurally, these residues are all located far from the membrane interface and are unlikely to be involved in PIP2 binding. Mutation and fluorophore-labelling may break their interactions with other residues, or block the ion conduction pathway, and the relevance of any PIP2-induced conformational changes at these sites to gating transitions, therefore, needs to be considered carefully (see Discussion). We also noticed that 219C-AD is active but loses PIP2 sensitivity. This residue is located in a connecting loop, and mutation or labelling may disrupt transduction of PIP2-triggered conformational changes, preventing closure of the channel pore (Fig. 2). Consistent with this interpretation, this residue showed only minimal PIP2-dependent changes in FRET (see below).

The intraliposome buffer was 10 mM HEPES, 450 mM KCl and 4 mM NMDG, pH7.5, and the extraliposome buffer was 10 mM HEPES, 50 μM KCl, 400 mM sorbitol and 4 mM NMDG, pH7.5. 86Rb+ uptake was measured at 15 min and normalized against the maximal 86Rb+ uptake in the presence of valinomycin. 86Rb+ uptake of fluorophore-labelled mutants is shown as 86Rb+ flux relative to wild type (Rb uptake, mean±s.e., n=3 in each case). Background level of 86Rb+ uptake (in liposomes with no protein) is marked by a red dashed line.

Movements of individual residues during PIP2-induced gating

To investigate the gating-associated motions of the KirBac1.1 cytoplasmic domain, 21 cysteine mutants, labelled with E/D or A/D FRET pairs, were reconstituted into POPE/POPG (3:1) liposomes with or without 1.25% PIP2, and apparent FRET efficiencies were measured as described in the Methods. Unlabelled mutant protein, reconstituted into liposomes, was used as a control to subtract background fluorescence. Proteinase K was used to digest the protein and break the fluorescence resonance energy transfer pathway, thereby allowing measurement of maximum donor emissions (Fig. 3a) after 5–60 min. Four mutants were tested with both A/D and E/D pairs. In each case, the directional change of FRET was the same, although there were large differences in individual FRET efficiencies, which may be due to different R0 of the FRET pairs, as well as the size and orientation of fluorophores (Table 1). Predicted FRET efficiencies were calculated from absolute distances between residues in KirBac1.1 crystal structures (2WLL, 1P7B), assuming two- or four-fold symmetry (Methods and Supplementary Table S1). There was a significant correlation between FRET-reported inter-subunit distances and distances predicted by the KirBac1.1 crystal structure (2WLL) (Fig. 3b). Although the 2WLL crystal structure actually exhibits a slight two-fold symmetry, the correlation was essentially identical whether the measured FRET efficiencies were compared with the predicted efficiencies with either two-fold (ab) or four-fold symmetry (a=b; Supplementary Fig. S2).

(a) Representative time course of FRET measurements by proteinase K-mediated donor dequenching. KirBac1.1 R151C and T264C tetramers were labelled by A/D mixtures, then reconstituted into liposomes (POPE:POPG=3:1). Proteinase K (0.08U per well) was added after 8 repeated readings (Fo) (T=5 min); Alexa-Fluor-546 emission (F, a.u.) was monitored until emission reached maximum (Fmax). (b) Cα–Cα distance between adjacent subunits of labelled residues predicted by FRET (mean±s.e., n=6–9 in each case) versus those present in the KirBac1.1 (2WLL) crystal structure. R and P values of correlation are 0.51 (P<0.010), 0.54 (P<0.006) for Cα–Cα distances calculated from measured FRET efficiencies in the absence (control) and presence of 1.25% PIP2, respectively.

There is a good overall correlation between the FRET-reported distances and those predicted by the crystal structure (Fig. 3b). There is a systematic deviation in reported distances for E/D versus A/D pairs, that is, E/D reports wider distances (~20 Å), when both pairs are examined at the same residue. The side chains of these residues (165, 177, 249 and 273) all potentially orient towards the pore axis in the KirBac1.1 crystal structure. Because the spacer arm of EDANS is shorter than that of Alexa-Fluor 546 (by >10 Å), the A/D pair will report shorter distances than the E/D pair. There is significant deviation between FRET-reported distances and crystallographic predictions at two residues in particular, 165C-AD and 308C-AD. Residue 308 is located at the outside edge of the cytoplasmic domain, and we suggest that the lack of correlation may be a result of the flexible nature of this region or the relative orientation of fluorophores within the tetramer. The latter interpretation seems potentially correct for 165C; whereas the FRET-reported distance for 165C-AD is considerably less than that predicted from 2WLL, the 165C-ED-reported distance is actually well correlated (Fig. 3b) and, moreover, 165C-ED is functionally much more active than 165C-AD (Fig. 2), suggesting a disruptive consequence of AD modification. Measured FRET efficiencies in the presence of PIP2 show slightly better correlation with predicted FRET efficiencies from the KirBac1.1 crystal structure, consistent with the crystal structure being in a closed state.

Residue motions suggest movements of secondary structures

The KirBac1.1 cytoplasmic domain consists of two major β-sheets, one (which we refer to as βI, including residues 186, 191, 252, 258, 260, 264 and 273; Fig. 4a) that is tilted ~45° relative to the membrane plane, and a second (βII, including residues 165, 177, 225 and 228; Fig. 4c), that is approximately parallel with the pore axis. Small, but reproducible differences in FRET efficiencies (up to 15%), were detected for most residues in the presence and absence of PIP2 (Table 1). Comparison of FRET efficiencies in the presence (closed) and absence (open) of PIP2 reveals important consistencies. First, in the presence of PIP2, all residues located at the top ends of βI move inwards relative to the central axis (264C, 260C, 258C, 186C and 191C), while residues at the bottom ends of βI (252C and 273C) and their attached short α-helix (249C and 277C) and β-sheets (280C and 283C) all move outwards. These data suggest a tilt motion of βI during PIP2-induced channel closure, with the top ends bending towards—and bottom ends bending away from—the pore axis (Fig. 4a,b). Second, all of the tested residues in βII and the associated loops and short helical stretches (219C, 225C, 228C, 235C, 180C, 177C, 165C, 306C and 308C) move inwards in the presence of PIP2, consistent with this whole region moving as a unit (Fig. 4c,d). Third, all cytoplasmic pore-lining residues (151, 264, 260, 258, 186, 191, 219 and 235), showed increased FRET efficiencies in the presence of PIP2, indicating that the cytoplasmic vestibule narrows throughout in the closed state (Fig. 4), consistent with accessibility data (Fig. 1).

Changes of apparent FRET efficiencies of KirBac1.1 cysteine mutants in the large β-sheet (βI, panel a, green and b) and small β-sheets (βII and associated loops, panel c, green and d) in presence versus absence of PIP2 (ΔEPIP2, mean±s.e., n=6–9 in each case). In a and c, Cα of the labelled residue is highlighted by spheres; residues demonstrating inward motion in the presence of PIP2 are coloured blue, those demonstrating outward motion are coloured red; the pore axis of KirBac1.1 is marked by dashed black line; amino acid residues in panels b and d are listed from top to bottom, along the axis indicated by a solid blue line in a and c.

Discussion

The growing number of K channels for which crystal structures are available (including KcsA17, MthK21, KvAP38, KirBac1.1 (ref. 15), Kv1.2 (ref. 39), NaK40,41 and Kir2.2 (ref. 16)) indicate that transmembrane domain structures are highly conserved. Crystallization of MthK in an open state provided the first direct view of an open K channel21, and revealed that removal of the major hydrophobic gate at the bundle crossing occurred by bending of pore forming α-helices away from the pore axis21,22. Similar structural changes have since been observed with open state crystal structures of KcsA42,43 and NaK41. For Kir and KirBac channels, there is also strong evidence for ligand-gating occurring at or near the bundle crossing25,26,44,45. Our accessibility data indicate a significant barrier to fluorophore accessibility at the bundle crossing (F146), with enhanced accessibility of A150C immediately beneath the bundle crossing, and no significant barrier below this level.

Rubidium flux assays indicate that PIP2 significantly inhibits almost all labelled mutant channels (Fig. 2), and our FRET studies reveal movements of multiple residues in the cytoplasmic domain in the presence of PIP2. In Rb flux assays, the potency of PIP2 inhibition of labelled mutants ranges from ~40–99% (Fig. 2), and, in most cases, inhibition will be incomplete, such that FRET-reported movements between open- and closed-conformations will be underestimations. In addition, uncertainties of fluorophore orientation factors preclude exact determinations of distances, but the direction of motion at each residue revealed by FRET measurements will be relatively robust. The qualitative patterns of directional movement (relative to the central axis of the channel) that then emerge (Fig. 4) are consistent with essentially rigid-body motions of the major secondary structural elements within the cytoplasmic Kir domain, similar to the proposal of Nishida et al. based on observation of two distinct conformations of the KirBac1.3-Kir3.1 chimera cytoplasmic domain46.

To visualize potential motions of the Kir domain, we generated 'cartoon' models for the open KirBac1.1 channel by modifying backbone coordinates of the closed KirBac1.1 (1P7B, Matlab, Mathworks Inc) in an attempt to match the constraints provided by the FRET measurements. Opening of the pore at the M2 helix bundle crossing was achieved by rotation and bending of TM2 at residue G134 (a potential hinge residue in K channels in general21,47) and then coupled rigid-body motion of the cytoplasmic domain was applied. The degree of bending of TM2, and rigid translation of the C-terminal domain were varied to minimize disagreement with the FRET data. The unknown orientation factors of the fluorophores and potential perturbation effects of mutations and chemical labelling severely limit the resolution of the FRET measurements and prohibit unambiguous assessment of absolute distances, but the qualitative structural constraints obtained by FRET measurements are reasonably well met by the 'cartoon' open model shown in Figure 5 (Supplementary Movie 1). The model was generated by tilting of βI, with the top end moving away from, and the bottom end towards, the pore axis (i), which widens the upper end of the cytoplasmic vestibule, and anticlockwise twist of βII leads to changes in the subunit interfaces and movement of βII away from the central axis (ii), which widens the cytoplasmic pore. The directional movements indicated by the FRET measurements are replicated for 19 out of 21 residues (Table 1), and are consistent with results obtained from other biochemical and biophysical studies on Kir channel open state conformations30,44,45, as well as predictions of molecular dynamic simulation studies24,47,48,49.

Eukaryotic and prokaryotic Kir channels have distinct and opposite responses to PIP2: while KirBac1.1 is closed by PIP2 binding, all eukaryotic Kir channels are opened by PIP2. The different response to PIP2 is likely to depend on critical differences in binding site orientation or on coupling of binding to the Kir domain gating machinery. Different structures of the loops that link the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains constituting the PIP2 binding pocket are likely to be important15,16. Indeed, a recently solved crystal structure of PIP2-bound Kir2.2 indicates key interacting residues that are absent from the linker loop of KirBac1.1 (ref. 8). A second PIP2-bound Kir3.2 structure reveals binding at a similar location35, and, moreover, PIP2 binding, which leads to channel activation in Kir3.2 channels, causes a twist in the major (β1) β-sheet that is qualitatively quite similar to that which we predict in the (PIP2-unbound) 'open' KirBac1.1. The eukaryotic Kir family exhibits sensitivity to a remarkably broad range of cytoplasmic ligands that are all likely to converge on similar conformational responses. Each subfamily from Kir1 to Kir7 has been shown to be activated by PIP2 (refs 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56), and biophysical analyses demonstrate that the unique ligands for different subfamilies (pH in Kir1 and Kir4; Na and G-protein βγ subunits in Kir3; ATP in Kir6) are convergent on the same process, such that kinetic models of gating implicitly involve the same gate as that activated by PIP2. This leads us to speculate that open-closed motions that we detect in the present study will be replicated in the ligand-induced gating of all eukaryotic inward rectifiers.

Methods

DNA manipulation and protein expression

DNA manipulation, expression and purification of KirBac1.1 cysteine substitution mutants are essentially as described previously12,19,57 except for changing the gel filtration buffer to 20 mM HEPES with 150 KCl and 5 mM DM, pH 7.5. Tetramer fractions were collected and concentrated to 3 mg ml−1 for chemical labelling with the maleimide form of fluorophore pairs. Cysteine-substituted KirBac1.1 mutants were labelled with EDANS C2 maleimide/DABCYL-plus C2 maleimide (E/D, ANASPEC), at protein:E:D ratio of 1:10:10, or with Alexa-Fluor-546 C5 maleimide (Invitrogen)/DABCYL-plus C2 maleimide (A/D) at a protein:A:D ratio of 1:2.5:10. Labelling reactions were performed at room temperature for 1 h,and, then, proteins were loaded onto a 5 ml Hitrap desalting column (GE Healthcare) to remove free probe. Labelled protein samples were collected and concentrated to 1.0 mg ml−1 (KirBac1.1-A/D) or 3.0 mg ml−1 (KirBac1.1-E/D) for reconstitution.

Accessibility assay using Alexa Fluor 488 C5 maleimide

Accessibility assays were performed at room temperature using labelling buffer containing ~400–500 ng of KirBac1.1 in labelling buffer (20 mM Hepes, 150 mM KCl, 5 mM DM, pH7.5) were immobilized on His-Sorb plates (Qiagen), and, then, the assay was started by adding AF-488 at final protein:probe ratio of 1:50, in the presence or absence of 10 μg ml−1 of diC8–PIP2. Free probes were removed by washing with labelling buffer (3×) and incorporation of AF-488 was monitored by emission at 525 nm with excitation wavelength of 485 nm. KirBac1.1 wild-type protein was used as control to estimate and subtract nonspecific labelling.

Reconstitution of labelled KirBac1.1 into liposomes

Lipids (3:1 POPE:POPG, Avanti Polar Lipids) were solubilized in buffer A (150 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) containing 37 mM CHAPS with or without 1.25% PIP2 (w/w). The KirBac1.1 cysteine mutants form tetrameric proteins with one cysteine in each monomer. Combinatorially, labelling with E/D or A/D FRET pairs gives six different configurations of donor and acceptor labels, four of which will have at least one donor and acceptor within a given tetramer (Supplementary Table S1). The lipids were mixed with fluorophore-labelled protein at a ratio of 100:3 for KirBac1.1-E/D and 100:1 for KirBac1.1-A/D. The lipid/protein mixture was incubated for 20 min at room temperature, and then loaded onto a Sephadex G-50 column pre-equilibrated with buffer A to remove CHAPS and to obtain reconstituted proteoliposomes.

FRET Measurements

FRET experiments were performed using a Synergy 2 fluorescence reader with excitation/emission wavelengths of 360/460 nm for KirBac1.1-E/D and 540/570 nm for KirBac1.1-A/D. Following 8 repeated readings, proteinase K solution was added to the proteoliposome sample at a final concentration of 0.08 U per well. Fluorescence was monitored until reaching a new stable plateau. Unlabelled protein samples were reconstituted into liposomes with or without PIP2 as controls to measure background fluorescence intensities. Fluorescence emission was measured before (Fo) and after proteinase digestion (Fmax). The apparent FRET efficiency (Eapp) is then given by the ratio of the quenched donor emission to the maximum donor emission:

Rubidium flux assay

Fluorophore-labelled KirBac1.1 cysteine mutants were reconstituted into liposomes containing 3:1 POPE:POPG with or without 1.25% PIP2, at protein:lipid ratio of 1:100, as described by Enkvetchakul et al.12,19 The KCl concentration inside and outside of the liposome was 450 mM and 50 μM, respectively. Rubidium uptake over 15 min was measured and normalized to valinomycin-dependent maximum uptake. All data are presented as mean±s.e. from three independent repeats.

Data analysis

For fluorescence measurements, data are expressed as mean±s.e. of multiple independent labelling and reconstitution experiments. Error propagation was used to calculate s.e. in Fig. 4. For calculating the apparent FRET efficiencies predicted by the crystal structure of KirBac1.1 (2WLL, or the 'open' structure model) in Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S2, the distances between α-carbon of FRET-measured residues at two adjacent subunits were used. For a tetramer with multiple donor and acceptor present, apparent FRET efficiencies (Eapp) were calculated based on resonance energy transfer rate theory as described in detail by Cheng et al.58 (Supplementary Table S1) using the following equation:

with the assumption that both donor and acceptor fluorophores are randomly incorporated into the KirBac1.1 tetramer. The Cα distance, predicted by experimentally measured apparent FRET efficiencies in Figure 3b, was obtained using the same FRET model by setting a=b. (Supplementary Table S1).

Additional information

How to cite this article: Wang, S. et al. Structural rearrangements underlying ligand-gating in Kir channels. Nat. Commun. 3:617 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1625 (2012)

References

Jan, L. Y. & Jan, Y. N. Voltage-gated and inwardly rectifying potassium channels. J. Physiol. 505 (Part 2), 267–282 (1997).

Nichols, C. G. & Lopatin, A. N. Inward rectifier potassium channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 59, 171–191 (1997).

McNicholas, C. M. et al. pH-dependent modulation of the cloned renal K+ channel, ROMK. Am. J. Physiol. 275, F972–981 (1998).

Schulte, U., Hahn, H., Wiesinger, H., Ruppersberg, J. P. & Fakler, B. pH-dependent gating of ROMK (Kir1.1) channels involves conformational changes in both N and C termini. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 34575–34579 (1998).

Krapivinsky, G., Krapivinsky, L., Wickman, K. & Clapham, D. E. G beta gamma binds directly to the G protein-gated K+ channel, IKACh. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 29059–29062 (1995).

Reuveny, E. et al. Activation of the cloned muscarinic potassium channel by G protein beta gamma subunits. Nature 370, 143–146 (1994).

Nichols, C. G. KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature 440, 470–476 (2006).

Hansen, S. B., Tao, X. & MacKinnon, R. Structural basis of PIP2 activation of the classical inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2. Nature 477, 495–498 (2011).

Suh, B. C. & Hille, B. PIP2 is a necessary cofactor for ion channel function: how and why? Annu. Rev. Biophys. 37, 175–195 (2008).

Xiao, J., Zhen, X. G. & Yang, J. Localization of PIP2 activation gate in inward rectifier K+ channels. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 811–818 (2003).

Durell, S. R. & Guy, H. R. A family of putative Kir potassium channels in prokaryotes. BMC Evol. Biol. 1, 14 (2001).

Enkvetchakul, D. et al. Functional characterization of a prokaryotic Kir channel. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 47076–47080 (2004).

Cheng, W. W., Enkvetchakul, D. & Nichols, C. G. KirBac1.1: it′s an inward rectifying potassium channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 133, 295–305 (2009).

Sun, S., Gan, J. H., Paynter, J. J. & Tucker, S. J. Cloning and functional characterization of a superfamily of microbial inwardly rectifying potassium channels. Physiol. Genomics 26, 1–7 (2006).

Kuo, A. et al. Crystal structure of the potassium channel KirBac1.1 in the closed state. Science 300, 1922–1926 (2003).

Tao, X., Avalos, J. L., Chen, J. & MacKinnon, R. Crystal structure of the eukaryotic strong inward-rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2 at 3.1 A resolution. Science 326, 1668–1674 (2009).

Doyle, D. A. et al. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science 280, 69–77 (1998).

D'Avanzo, N., Cheng, W. W., Doyle, D. A. & Nichols, C. G. Direct and specific activation Of human inward rectifier K+ channels by membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 37129–37132 (2010).

Enkvetchakul, D., Jeliazkova, I. & Nichols, C. G. Direct modulation of Kir channel gating by membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35785–35788 (2005).

D′Avanzo, N., Cheng, W. W., Doyle, D. A. & Nichols, C. G. Direct and specific activation of human inward rectifier K+ channels by membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 37129–37132 (2010).

Jiang, Y. et al. The open pore conformation of potassium channels. Nature 417, 523–526 (2002).

Jiang, Y. et al. Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature 417, 515–522 (2002).

Kuo, A., Domene, C., Johnson, L. N., Doyle, D. A. & Venien-Bryan, C. Two different conformational states of the KirBac3.1 potassium channel revealed by electron crystallography. Structure 13, 1463–1472 (2005).

Haider, S., Khalid, S., Tucker, S. J., Ashcroft, F. M. & Sansom, M. S. Molecular dynamics simulations of inwardly rectifying (Kir) potassium channels: a comparative study. Biochemistry 46, 3643–3652 (2007).

Phillips, L. R., Enkvetchakul, D. & Nichols, C. G. Gating dependence of inner pore access in inward rectifier K(+) channels. Neuron 37, 953–962 (2003).

Phillips, L. R. & Nichols, C. G. Ligand-induced closure of inward rectifier Kir6.2 channels traps spermine in the pore. J. Gen. Physiol. 122, 795–804 (2003).

Cuello, L. G., Cortes, D. M., Jogini, V., Sompornpisut, A. & Perozo, E. A molecular mechanism for proton-dependent gating in KcsA. FEBS Lett. 584, 1126–1132 (2010).

Thompson, A. N., Posson, D. J., Parsa, P. V. & Nimigean, C. M. Molecular mechanism of pH sensing in KcsA potassium channels. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 6900–6905 (2008).

Miloshevsky, G. V. & Jordan, P. C. Open-state conformation of the KcsA K+ channel: Monte Carlo normal mode following simulations. Structure 15, 1654–1662 (2007).

Riven, I., Kalmanzon, E., Segev, L. & Reuveny, E. Conformational rearrangements associated with the gating of the G protein-coupled potassium channel revealed by FRET microscopy. Neuron 38, 225–235 (2003).

Grottesi, A., Domene, C., Haider, S. & Sansom, M. S. Molecular dynamics simulation approaches to K channels: conformational flexibility and physiological function. IEEE Trans. Nano. Biosci. 4, 112–120 (2005).

Lee, J. R. & Shieh, R. C. Structural changes in the cytoplasmic pore of the Kir1.1 channel during pHi-gating probed by FRET 16, 29 (2009).

Clarke, O. B. et al. Domain reorientation and rotation of an intracellular assembly regulate conduction in Kir potassium channels. Cell 141, 1018–1029 (2010).

Zhou, W. & Jan, L. Y. A twist on potassium channel gating. Cell 141, 920–922 (2010).

Whorton, M. R. & Mackinnon, R. Crystal Structure of the Mammalian GIRK2 K(+) Channel and Gating Regulation by G Proteins, PIP(2), and Sodium. Cell 147, 199–208 (2011).

Pegan, S. et al. Cytoplasmic domain structures of Kir2.1 and Kir3.1 show sites for modulating gating and rectification. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 279–287 (2005).

Nishida, M. & MacKinnon, R. Structural basis of inward rectification: cytoplasmic pore of the G protein-gated inward rectifier GIRK1 at 1.8 A resolution. Cell 111, 957–965 (2002).

Jiang, Y. et al. X-ray structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature 423, 33–41 (2003).

Long, S. B., Campbell, E. B. & Mackinnon, R. Crystal structure of a mammalian voltage-dependent Shaker family K+ channel. Science 309, 897–903 (2005).

Shi, N., Ye, S., Alam, A., Chen, L. & Jiang, Y. Atomic structure of a Na+- and K+-conducting channel. Nature 440, 570–574 (2006).

Alam, A. & Jiang, Y. High-resolution structure of the open NaK channel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 30–34 (2009).

Cuello, L. G., Jogini, V., Cortes, D. M. & Perozo, E. Structural mechanism of C-type inactivation in K(+) channels. Nature 466, 203–208 (2010).

Cuello, L. G. et al. Structural basis for the coupling between activation and inactivation gates in K(+) channels. Nature 466, 272–275 (2010).

Gupta, S. et al. Conformational changes during the gating of a potassium channel revealed by structural mass spectrometry. Structure 18, 839–846 (2010).

Paynter, J. J. et al. Functional complementation and genetic deletion studies of KirBac channels: activatory mutations highlight gating-sensitive domains. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 40754–40761 (2010).

Nishida, M., Cadene, M., Chait, B. T. & MacKinnon, R. Crystal structure of a Kir3.1-prokaryotic Kir channel chimera. EMBO J. 26, 4005–4015 (2007).

Grottesi, A., Domene, C., Hall, B. & Sansom, M. S. Conformational dynamics of M2 helices in KirBac channels: helix flexibility in relation to gating via molecular dynamics simulations. Biochemistry 44, 14586–14594 (2005).

Haider, S., Grottesi, A., Hall, B. A., Ashcroft, F. M. & Sansom, M. S. Conformational dynamics of the ligand-binding domain of inward rectifier K channels as revealed by molecular dynamics simulations: toward an understanding of Kir channel gating. Biophys. J. 88, 3310–3320 (2005).

Shrivastava, I. H., Capener, C. E., Forrest, L. R. & Sansom, M. S. Structure and dynamics of K channel pore-lining helices: a comparative simulation study. Biophys. J. 78, 79–92 (2000).

Huang, C. L., Feng, S. & Hilgemann, D. W. Direct activation of inward rectifier potassium channels by PIP2 and its stabilization by Gbetagamma. Nature 391, 803–806 (1998).

Shyng, S. L. & Nichols, C. G. Membrane phospholipid control of nucleotide sensitivity of KATP channels. Science 282, 1138–1141 (1998).

Sui, J. L., Petit-Jacques, J. & Logothetis, D. E. Activation of the atrial KACh channel by the betagamma subunits of G proteins or intracellular Na+ ions depends on the presence of phosphatidylinositol phosphates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 1307–1312 (1998).

Leung, Y. M., Zeng, W. Z., Liou, H. H., Solaro, C. R. & Huang, C. L. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and intracellular pH regulate the ROMK1 potassium channel via separate but interrelated mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10182–10189 (2000).

Schulze, D., Krauter, T., Fritzenschaft, H., Soom, M. & Baukrowitz, T. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) modulation of ATP and pH sensitivity in Kir channels. A tale of an active and a silent PIP2 site in the N terminus. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 10500–10505 (2003).

Du, X. et al. Characteristic interactions with phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate determine regulation of kir channels by diverse modulators. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 37271–37281 (2004).

Rapedius, M. et al. Long chain CoA esters as competitive antagonists of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate activation in Kir channels. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30760–30767 (2005).

Wang, S., Alimi, Y., Tong, A., Nichols, C. G. & Enkvetchakul, D. Differential roles of blocking ions in KirBac1.1 tetramer stability. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 2854–2860 (2009).

Cheng, W., Yang, F., Takanishi, C. L. & Zheng, J. Thermosensitive TRPV channel subunits coassemble into heteromeric channels with intermediate conductance and gating properties. J. Gen. Physiol. 129, 191–207 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Beth Cotner-Gohara and Shawn Yackly for their technical support in using the Synergy2 reader, Dr Nazzareno D'Avanzo and Wayland W.L. Cheng for constructive discussions. This work was supported by NIH grants HL54171 and HL45742 (to C.G.N.), DK069424 (to D.E.) and American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship 10POST4280056 (to S.W.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.W., S.J.L., D.E. and C.G.N. designed the study. S.W., S.J.L., D.E. and S.H. performed experiments and analysis. S.W., S.J.L. and C.G.N. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S2 and Supplementary Table S1 (PDF 833 kb)

Supplementary Movie 1

The KirBac1.1 crystal structure (1P7B, gray) and a morph transition to the 'open' model described in the text (red). The channel is first viewed from below, through the central axis, and the channel is shown opening and closing two times. Two subunits (B, D) and transmembrane domain of the two remaining subunits(A, C) are then removed. Two dashed lines are drawn to illustrate the distance changes between the subunits at the top and bottom of the b-1 sheet during two opening and closing movements of the cytoplasmic domain. Finally the transmembrane domain of the two subunits are restored and they are rotated to be viewed from the side for another two opening and closing movements. (MOV 8281 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., Lee, SJ., Heyman, S. et al. Structural rearrangements underlying ligand-gating in Kir channels. Nat Commun 3, 617 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1625

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1625

This article is cited by

-

New Structural insights into Kir channel gating from molecular simulations, HDX-MS and functional studies

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Structural dynamics of potassium-channel gating revealed by single-molecule FRET

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology (2016)

-

Secondary anionic phospholipid binding site and gating mechanism in Kir2.1 inward rectifier channels

Nature Communications (2013)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.