Abstract

Generalized hydrodynamics predicts universal ballistic transport in integrable lattice systems when prepared in generic inhomogeneous initial states. However, the ballistic contribution to transport can vanish in systems with additional discrete symmetries. Here we perform large scale numerical simulations of spin dynamics in the anisotropic Heisenberg XXZ spin 1/2 chain starting from an inhomogeneous mixed initial state which is symmetric with respect to a combination of spin reversal and spatial reflection. In the isotropic and easy-axis regimes we find non-ballistic spin transport which we analyse in detail in terms of scaling exponents of the transported magnetization and scaling profiles of the spin density. While in the easy-axis regime we find accurate evidence of normal diffusion, the spin transport in the isotropic case is clearly super-diffusive, with the scaling exponent very close to 2/3, but with universal scaling dynamics which obeys the diffusion equation in nonlinearly scaled time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Integrable models, such as the classical Kepler problem, harmonic oscillators, the planar Ising problem and so on, form cornerstones of our understanding of nature. Their equilibrium physics is usually well understood, even for the most complicated among integrable models, for example, the ones solvable by the Bethe ansatz1. Non-equilibrium physics of quantum systems on the other hand is much less understood2, particularly when going beyond the simplest integrability of quadratic models. This theoretical gap is becoming even more apparent with the advancement of experimental methods that are offering us analogue simulation of models beyond the capability of our best theoretical and numerical methods3,4.

Non-equilibrium dynamics of integrable quantum systems is thus one of the main current focuses of both theoretical and experimental condensed matter physics5. A macroscopic number of conservation laws existing in such systems6 provide a variety of ways to break ergodicity, manifesting, for instance, in equilibration processes to non-thermal states or ballistic high-temperature transport of conserved quantities, such as energy, magnetization or charge. A naive classical reasoning might be that, because integrable systems are distinguished by constants of motion that force the dynamics to be simple and almost periodic (for example, orbits winding up the torus), one should expect to see ballistic transport. We shall demonstrate that this picture, while being correct for trivially integrable noninteracting models, such as harmonic oscillator chains7, can in fact be wrong for an interacting quantum integrable model.

Recently, a generalization of hydrodynamics has been put forward8,9 which successfully predicts ballistic currents and scaled density profiles of integrable interacting systems quenched from inhomogeneous initial states10,11,12,13,14,15, which is a convenient method to study relaxation and non-equilibrium transport. In this protocol, the system is prepared in the state where the left and the right part, for x<0 and x>0, respectively, are in different equilibrium states, and then, at t=0, let to evolve with a homogeneous interacting Hamiltonian. However, when ballistic transport is prohibited due to generic symmetries, such as is the case for spin transport in the anisotropic Heisenberg spin chain in the easy-axis (Ising) regime, this theory makes no prediction.

In extended interacting integrable system a macroscopic number of local conservation laws exists, in number proportional to the number of degrees of freedom, which can be exploited to develop generalized hydrodynamics8. This theory for typical inhomogeneous initial states predicts ballistic scaling f(ξ=x/t) of densities and currents of conserved quantities, such as energy, charge or magnetization. However, in systems with parity  symmetries, such as particle-hole exchange (or spin reversal), and for observables that are odd under the parity and initial states that are symmetric under the combined parity and spatial reflection x→−x, the ballistic contribution to transport can vanish. In fact, vanishing ballistic transport channel can then be related to the absence of local or quasi-local conserved charges with odd parity6,16. This means that the transported conserved quantity at x=0 grows slower than linear with t.

symmetries, such as particle-hole exchange (or spin reversal), and for observables that are odd under the parity and initial states that are symmetric under the combined parity and spatial reflection x→−x, the ballistic contribution to transport can vanish. In fact, vanishing ballistic transport channel can then be related to the absence of local or quasi-local conserved charges with odd parity6,16. This means that the transported conserved quantity at x=0 grows slower than linear with t.

Here we propose a conjecture, based on large scale simulations, that a quench from an inhomogeneous initial state will in such cases generically result in diffusive spin dynamics. We demonstrate our results on the anisotropic Heisenberg chain (XXZ model). However, we stress that the XXZ model goes beyond being a mere toy model—it has been instrumental in the development of quantum integrability17,18 and describes interaction in real spin chain materials19. Remarkably, in the case of isotropic Heisenberg interaction, spin relaxation is super-diffusive but with universal scaling dynamics which obey the standard diffusion equation in nonlinearly scaled time. Our results thus reveal a surprising property of an important integrable model as well as pose a challenge to theories which at present are unable to account for our observations. Because the parity symmetry is ubiquitous, our set-up should be widely applicable, for instance, we predict a similar physics in the one-dimensional (1D) Hubbard model.

Results

The set-up

The Hamiltonian of the XXZ chain of n sites reads

where Δ is the anisotropy parameter and  are the spin 1/2 operators, with Cartesian component γ=1, 2, 3, expressed in term of Pauli matrices

are the spin 1/2 operators, with Cartesian component γ=1, 2, 3, expressed in term of Pauli matrices  (we use units J=ħ=1). The Hamiltonian preserves the total magnetization,

(we use units J=ħ=1). The Hamiltonian preserves the total magnetization,  ,

,  . We are going to study the spin transport satisfying the continuity equation

. We are going to study the spin transport satisfying the continuity equation  with the current

with the current

The existence of spin-reversal parity  ,

,  and odd current jxS=−Sjx, implies an absence of ballistic transport channels based on local conserved charges20. We are going to simulate the time evolution of an initial inhomogeneous state composed of two halves with opposite magnetizations.

and odd current jxS=−Sjx, implies an absence of ballistic transport channels based on local conserved charges20. We are going to simulate the time evolution of an initial inhomogeneous state composed of two halves with opposite magnetizations.

To this end we choose a product initial state described by a density operator ρ,

where the parameter μ∈[−1, 1] determines the initial magnetization, being  . Each of the initial halves can be thought of as being in equilibrium state

. Each of the initial halves can be thought of as being in equilibrium state  at very high temperature and finite magnetization. We are therefore studying high-energy non-equilibrium physics of the model. While the initial state is pure for |μ|=1 (a fully polarized domain wall), evolution of which has been studied in the past21, the choice of a mixed state offers several important advantages: it is generic and not plagued by the speciality of μ=1 at Δ>1 for which the dynamics freezes due to the proximity to a gapped eigenstate22, and it is, for small μ, better suited for numerical simulations. This allows us to study significantly longer timescales as compared to existing literature and infer the scaling functions. We also mention that such an initial state can be thought of as representing an ensemble of pure states with randomized angle ϕ on the Bloch sphere (Methods section).

at very high temperature and finite magnetization. We are therefore studying high-energy non-equilibrium physics of the model. While the initial state is pure for |μ|=1 (a fully polarized domain wall), evolution of which has been studied in the past21, the choice of a mixed state offers several important advantages: it is generic and not plagued by the speciality of μ=1 at Δ>1 for which the dynamics freezes due to the proximity to a gapped eigenstate22, and it is, for small μ, better suited for numerical simulations. This allows us to study significantly longer timescales as compared to existing literature and infer the scaling functions. We also mention that such an initial state can be thought of as representing an ensemble of pure states with randomized angle ϕ on the Bloch sphere (Methods section).

Scaling exponents

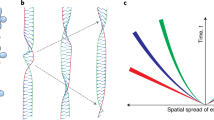

We focus our efforts on Δ≥1 where there are no analytic results known for the magnetization transport, and the method8,9 only predicts vanishing ballistic contribution. Two representative examples of a time evolved state ρ(t), namely the spin and current profiles  , j(x, t)=trρ(t)jx, are shown in Fig. 1. To obtain the exact type of transport we shall quantitatively study equilibration of magnetization, in particular the scaling of spin and current profiles as well as the transferred magnetization between the two halves, whose asymptotic scaling power α characterizes the transport type,

, j(x, t)=trρ(t)jx, are shown in Fig. 1. To obtain the exact type of transport we shall quantitatively study equilibration of magnetization, in particular the scaling of spin and current profiles as well as the transferred magnetization between the two halves, whose asymptotic scaling power α characterizes the transport type,

Time evolution of spin density  (a,b) and current (c,d) profile j(x, t)=tr(ρ(t)jx) for the isotropic point Δ=1 (a,c), and Δ=2 (b,d), following an inhomogeneous quench. One can see that the spreading is much faster for Δ=1, in both cases though it is slower than ballistic. Dashed green curves guide the eye towards scaling x∼t2/3 in a, and x∼t1/2 in (b). Data are shown for n=320 and small initial polarization μ=π/1,800.

(a,b) and current (c,d) profile j(x, t)=tr(ρ(t)jx) for the isotropic point Δ=1 (a,c), and Δ=2 (b,d), following an inhomogeneous quench. One can see that the spreading is much faster for Δ=1, in both cases though it is slower than ballistic. Dashed green curves guide the eye towards scaling x∼t2/3 in a, and x∼t1/2 in (b). Data are shown for n=320 and small initial polarization μ=π/1,800.

where j(0, t) is the current at the half-cut. For α=1/2 the transport is diffusive, for 1/2<α<1 it is called super-diffusive, and finally, α=1 corresponds to ballistic transport. We note that the transport type is connected to current–current correlation function via Green–Kubo linear response theory. In case of diffusive transport, the spin density satisfies the diffusion equation. This notion of diffusion does not necessarily correspond to De Gennes phenomenological theory of spin diffusion which, under much stronger assumptions, in 1D implies 1/ dependence of local spin density autocorrelation function23,24.

dependence of local spin density autocorrelation function23,24.

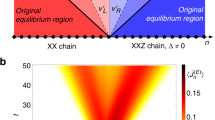

We evolved the initial state ρ(0) (3) up to long times (of order t≈160) and set large enough n so that there was no significant finite size effects. From the data we then infer the exponent α using equation (4), see Fig. 2a,b for representative plots. Dependence of the exponent α on Δ is summarized in Fig. 2c. While the transport is found to be ballistic for Δ<1, expectedly so for the integrable system, also known rigorously16, at Δ≥1 we find rather clear non-ballistic relaxation. In particular, at Δ=1 it is super-diffusive while for Δ>1 the transport is diffusive, observed in driven steady-state setting25,26 as well as in the Hamiltonian one24,27,28,29,30. At Δ=1 we also observe small dependence of α on μ. While for small μ, that is, small deviations from an infinite temperature state ρ∼ , the exponent is close to 2/3, closer to pure state μ=1 it appears to be closer to ≈3/5 (we note that a different numerical procedure is used in the two regimes, see Methods).

, the exponent is close to 2/3, closer to pure state μ=1 it appears to be closer to ≈3/5 (we note that a different numerical procedure is used in the two regimes, see Methods).

(a,b) Local exponent α(t) calculated as a numerical log-derivative d log Δs(t)/d log t for Δ=1 (a) and Δ=2 (b) (dashed lines indicate exponents 2/3 and 1/2, respectively, while dashed lines in the insets show best power-law fits to Δs(t)—red curve), both for μ=π/1,800. (c) Conjecture for the dependence α(Δ) at high temperatures and small μ. The inset shows the diffusion constant obtained from Fick’s law for various values of Δ in the diffusive regime, converging to a finite value at large Δ (agreeing with ref. 28). (d) Dependence on μ for Δ=1 shows a small but significant change in the behaviour: for μ≈1 it is closer to α=3/5 while for small μ it becomes close to α=2/3 (dashed). The blue (circles) and red (crosses) symbols represent wave function and density operator evolutions respectively. We average over samples of 10–130 random initial wave-functions for each blue data point. For intermediate μ the error-bars (denoting the estimated s.d.) are larger since the simulation is less efficient in that regime (Methods section).

Scaling functions

The scaling of the transferred magnetization unequivocally shows a surprising non-ballistic transport in an integrable system which, however, has been observed and discussed before in related contexts, namely within local quench and linear response theory24,27,28,29,30 and boundary driven Lindblad approach25,26. But here we can do still more. In Fig. 3 we demonstrate that the spin profiles can be described by a function of a single-scaling variable x/tα—profiles at large times collapse to a single curve. In addition, the profiles of current and magnetization are proportional to each other at different times (Fig. 3c,d), therefore validating Fick’s law j=−D∇s where the behaviour of the diffusion constant D with respect to the anisotropy Δ is shown in the inset of Fig. 2c. This comes as no surprise in the diffusive regime Δ>1 where the scaling function of the magnetization (Fig. 3b) is simply the error function  . However, the same can not be said for the isotropic point Δ=1. Proportionality between the magnetization gradient and the current profile (Fig. 3c), this time with a time-dependent ratio

. However, the same can not be said for the isotropic point Δ=1. Proportionality between the magnetization gradient and the current profile (Fig. 3c), this time with a time-dependent ratio  , suggests a diffusion equation in a scaled time

, suggests a diffusion equation in a scaled time

Scaling of density and current profiles with x/tα. In (a,b) we show the scaling of magnetization profiles, (a) for Δ=1 using α=2/3, and (b) for Δ=2 and using α=1/2 (note that the points for different times overlap almost perfectly; the insets show the convergence of the relative root-mean-square difference (in %) between data s(x, t) and scaled erf-profiles (see text) as a function of time). Frames (c,d) show the emergence of Fick’s law at late times (shown at t=160), comparing current profiles (red) to gradients of spin density (blue)—both indistinguishable from Gaussians, for Δ=1 in (c) and Δ=2 in (d). In all plots the system size is n=320.

which again yields error function profile with a different scaling variable  with K=2.33±0.03. In Fig. 3a we compare numerical profiles with the error function, again finding good agreement within accuracy of our simulations. Therefore, the scaling function is, in both cases, Δ=1 and Δ>1, the error function, the difference being only in the scaling variable which is x/t2/3 at the super-diffusive isotropic point. This result is surprising, as anomalous diffusion is usually associated with Levy processes and hence long (non-Gaussian) tails in the profiles. Here it seems it all amounts to a nonlinear rescaling of time. Theoretical explanation of this effect is urgent.

with K=2.33±0.03. In Fig. 3a we compare numerical profiles with the error function, again finding good agreement within accuracy of our simulations. Therefore, the scaling function is, in both cases, Δ=1 and Δ>1, the error function, the difference being only in the scaling variable which is x/t2/3 at the super-diffusive isotropic point. This result is surprising, as anomalous diffusion is usually associated with Levy processes and hence long (non-Gaussian) tails in the profiles. Here it seems it all amounts to a nonlinear rescaling of time. Theoretical explanation of this effect is urgent.

Entanglement entropy and simulation complexity

Finally, we mention a numerical observation that explains why we can simulate dynamics to such long times, and is an interesting property on its own. We use a time-dependent density matrix renormalization group method (tDMRG), see Methods. The efficiency of tDMRG depends on the entanglement entropy, that is, for pure state evolution on the Von Neumann entropy  of the reduced state ρA=trA|Ψ〉〈Ψ|, whereas for mixed states evolution on an analogous operator space entanglement entropy S#, (ref. 31) of a vectorised density operator ρ. When starting with a typical product initial state both entropies typically grow linearly with time, regardless of the system being integrable or not32,33, causing exponentially fast growth of complexity and with it a failure of these numerical methods. In our case though, see Fig. 4, entropies grow much slower, namely in a power-law fashion

of the reduced state ρA=trA|Ψ〉〈Ψ|, whereas for mixed states evolution on an analogous operator space entanglement entropy S#, (ref. 31) of a vectorised density operator ρ. When starting with a typical product initial state both entropies typically grow linearly with time, regardless of the system being integrable or not32,33, causing exponentially fast growth of complexity and with it a failure of these numerical methods. In our case though, see Fig. 4, entropies grow much slower, namely in a power-law fashion

with β being <1. The most efficient simulations have been possible with density operators for small μ where the exponent β is typically between 0.3 and 0.5.

Discussion

Our numerical results can be interpreted as an evidence of normal spin diffusion and spin Fick’s law in the easy-axis anisotropic Heisenberg chain (for anisotropy Δ>1), with spin density satisfying the diffusion equation on large scales. Besides the case Δ=2 shown here, we provide additional data for Δ=1.05, 1.1, 1.3, 1.5 demonstrating a clear convergence of the diffusive scaling exponents α=1/2 in all massive cases (Supplementary Note 1), and data for massless cases Δ=0, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9 which indicate convergence to ballistic exponent α=1 (Supplementary Note 2). While for generic, non-spin-reversal-symmetric initial states, the dominant contribution to transport is ballistic as determined by generalized hydrodynamics (or generalized 1D Euler’s equations)8,9,13,14,15, the next-to-leading term is now clearly predicted to be diffusive, as following from our work. However, a theoretical explanation, or even derivation of a diffusive contribution to transport in an integrable system with a macroscopic number of conservation laws is still pending. Even more surprising is the discovery of anomalous super-diffusive transport in the isotropic case (Δ=1) with the scaling exponent equal to or very close to 2/3. While this might suggest a behaviour described by KPZ (Kardar–Parisi–Zhang) universality class, we find that asymptotic spin density profiles obey the nonlinearly scaled diffusion equation and are distinct from the KPZ profiles. One might conjecture that the scaling exponent 2/3 is a consequence of SU(2) symmetry and not the fact that the model there corresponds to the marginal critical point Δ=1. This would be consistent with observed anomalous super-diffusive scalings in SU(4) spin ladders in the set-up of driven steady-state Lindblad dynamics34 where the scaling exponent appears to be α=3/5. Curiously, all scaling exponents observed in this work (1/1, 1/2, 2/3, 3/5) are ratios of subsequent Fibonacci numbers35.

Methods

Numerical procedures

The time evolution is performed by means of the tDMRG algorithm36,37. In particular, for small μ data (which is mostly reported here) the most efficient was the matrix product density operator version of tDMRG, with which we could reach times of the order t≃200 for system size n≃2t using bond dimensions 50–200 resulting in relative truncation errors <1%. One the other hand, for μ≈1 (close to domain wall pure state), the pure state version of tDMRG becomes more efficient as the corresponding entanglement entropy scaling exponents β are smaller. The two approaches appear to complement one another as can be seen in Fig. 2d. Neither approach allows us to observe long times in the intermediate region of μ, where the exponents β become closer to 1.

In order to simulate the desired density operator by evolving pure states we define a set of initial states

where  is simply the Bloch sphere representation of a 2-level system and the φx are uniform independent random numbers in the range [0, 2π). The density matrix is then obtained as an ensemble average over a set of such pure random states

is simply the Bloch sphere representation of a 2-level system and the φx are uniform independent random numbers in the range [0, 2π). The density matrix is then obtained as an ensemble average over a set of such pure random states  . It is clear that an increasingly large set of random states is needed as the magnetization approaches μ→0, where the matrix product density operator simulation is favourable anyway.

. It is clear that an increasingly large set of random states is needed as the magnetization approaches μ→0, where the matrix product density operator simulation is favourable anyway.

Data availability

Data are available on request from the authors.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Ljubotina, M. et al. Spin diffusion from an inhomogeneous quench in an integrable system. Nat. Commun. 8, 16117 doi: 10.1038/ncomms16117 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Takahashi, M. Thermodynamics of One-Dimensional Solvable Models Cambridge University Press (1999).

Polkovnikov, A., Sengupta, K., Silva, A. & Vengalattore, M. Colloquium: nonequilibrium dynamics of closed interacting quantum systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 863–883 (2011).

Bloch, I., Dalibard, J. & Nascimbene, S. Quantum simulations with ultracold quantum gases. Nat. Phys. 8, 267–276 (2012).

Choi, J.-Y. et al. Exploring the many-body localization transition in two dimensions. Science 352, 1547–1552 (2016).

Calabrese, P., Essler, F. H. L. & Mussardo, G. Special issue on ‘Quantum Integrability in Out of Equilibrium Systems’. J. Stat. Mech. 2016, 064001 (2016).

Ilievski, E., Medenjak, M., Prosen, T. & Zadnik, L. Quasilocal charges in integrable lattice systems. J. Stat. Mech. 2016, 064008 (2016).

Rieder, Z., Lebowitz, J. L. & Lieb, E. Properties of a harmonic crystal in a stationary nonequilibrium state. J. Math. Phys. 8, 1073–1078 (1967).

Castro-Alvaredo, O. A., Doyon, B. & Yoshimura, T. Emergent hydrodynamics in integrable quantum systems out of equilibrium. Phys. Rev. X 6, 041065 (2016).

Bertini, B., Collura, M., De Nardis, J. & Fagotti, M. Transport in out-of-equilibrium XXZ chains: exact profiles of charges and currents. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 207201 (2016).

Ruelle, D. Natural nonequilibrium states in quantum statistical mechanics. J. Stat. Phys. 98, 57–75 (2000).

Bernard, D. & Doyon, B. Non-equilibrium steady-states in conformal field theory. Ann. Inst. Henri Poincaré 16, 113–161 (2015).

Bhaseen, M. J., Doyon, B., Lucas, A. & Schalm, K. Energy flow in quantum critical systems far from equilibrium. Nat. Phys. 11, 509–514 (2015).

Ilievski, E. & De Nardis, J. On the microscopic origin of ideal conductivity. Preprint at http://arXiv.org/abs/1702.02930 (2017).

Bulchandani, V. B., Vasseur, R., Karrasch, C. & Moore, J. E. Bethe-Boltzmann hydrodynamics and spin transport in the XXZ chain. Preprint at http://arXiv.org/abs/1702.06146 (2017).

Doyon, B., Spohn, H. & Yoshimura, T. A geometric viewpoint on generalized hydrodynamics. Preprint at http://arXiv.org/abs/1704.04409 (2017).

Prosen, T. Open XXZ spin chain: nonequilibrium steady state and a strict bound on ballistic transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 217206 (2011).

Bethe, H. On the theory of metals, I. Eigenvalues and Eignefunctions of a linear chain of atoms. Zeits. Physik 74, 205–226 (1931).

Baxter, R. J. Exactly Solved Models in Statistical Mechanics (Courier Corporation, 1982).

Hlubek, N. et al. Spinon heat transport and spin–phonon interaction in the spin-1/2 Heisenberg chain cuprates Sr2CuO3 and SrCuO2 . J. Stat. Mech. 2012, P03006 (2012).

Zotos, X., Naef, F. & Prelovšek, P. Transport and conservation laws. Phys. Rev. B 55, 11029–11032 (1997).

Gobert, D., Kollath, C., Schollwöck, U. & Schütz, G. Real-time dynamics in spin-1/2 chains with adaptive time-dependent density matrix renormalization group. Phys. Rev. E 71, 036102 (2005).

Gochev, I. G. Contribution to the theory of plane domain walls in a ferromagnet. Sov. Phys. JETP 58, 115–119 (1983).

Fabricius, K. & McCoy, B. M. Spin diffusion and the spin-1/2 XXZ chain at T=∞ from exact diagonalization. Phys. Rev. B 57, 8340–8347 (1998).

Sirker, J., Pereira, R. G. & Affleck, I. Conservation laws, integrability, and transport in one-dimensional quantum systems. Phys. Rev. B 83, 035115 (2011).

Prosen, T. & Žnidarič, M. Matrix product simulation of non-equilibrium steady states of quantum spin chains. J. Stat. Mech. 2009, P02035 (2009).

Žnidarič, M. Spin transport in a one-dimensional anisotropic Heisenberg model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 220601 (2011).

Steinigeweg, R. & Gemmer, J. Density dynamics in translationally invariant spin-1/2 chains at high temperatures: a current-autocorrelation approach to finite time and length scales. Phys. Rev. B 80, 184402 (2009).

Karrasch, C., Moore, J. E. & Heidrich-Meisner, F. Real-time and real-space spin and energy dynamics in one-dimensional spin-1/2 systems induced by local quantum quenches at finite temperatures. Phys. Rev. B 89, 075139 (2014).

Steinigeweg, R., Gemmer, J. & Brenig, W. Spin-current autocorrelations from single pure-state propagation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 120601 (2014).

Steinigeweg, R. et al. Real-time broadening of nonequilibrium density profiles and the role of the specific initial-state realization. Phys. Rev. B 95, 035155 (2017).

Prosen, T. & Pižorn, I. Operator space entanglement entropy in a transverse Ising chain. Phys. Rev. A 76, 032316 (2007).

Calabrese, P. & Cardy, J. Evolution of entanglement entropy in one-dimensional systems. J. Stat. Mech. 2005, P04010 (2005).

De Chiara, G., Montangero, S., Calabrese, P. & Fazio, R. Entanglement entropy dynamics of Heisenberg chains. J. Stat. Mech. 2006, P03001 (2006).

Žnidarič, M. Magnetization transport in spin ladders and next-nearest-neighbor chains. Phys. Rev. B 88, 205135 (2013).

Popkov, V., Schadschneider, A., Schmidt, J. & Schütz, G. M. Fibonacci family of dynamical universality classes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 12645–12650 (2015).

Vidal, G. Efficient simulation of one-dimensional quantum many-body systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 040502 (2004).

Schollwöck, U. The density-matrix renormalization group in the age of matrix product states. Ann. Phys. 326, 96–192 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge support from ERC grant OMNES, as well as grants J1-7279, N1-0025 and P1-0044 of the Slovenian Research Agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.P. proposed the project, M.L. performed the simulations and all authors contributed to the analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ljubotina, M., Žnidarič, M. & Prosen, T. Spin diffusion from an inhomogeneous quench in an integrable system. Nat Commun 8, 16117 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms16117

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms16117

This article is cited by

-

Universality class of a spinor Bose–Einstein condensate far from equilibrium

Nature Physics (2024)

-

Noncommuting conserved charges in quantum thermodynamics and beyond

Nature Reviews Physics (2023)

-

The theory of generalised hydrodynamics for the one-dimensional Bose gas

AAPPS Bulletin (2023)

-

Long-lived phantom helix states in Heisenberg quantum magnets

Nature Physics (2022)

-

Kardar–Parisi–Zhang universality in a one-dimensional polariton condensate

Nature (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.