Abstract

The challenge of safe hydrogen storage has limited the practical application of solar-driven photocatalytic water splitting. It is hard to isolate hydrogen from oxygen products during water splitting to avoid unwanted reverse reaction or explosion. Here we propose a multi-layer structure where a carbon nitride is sandwiched between two graphene sheets modified by different functional groups. First-principles simulations demonstrate that such a system can harvest light and deliver photo-generated holes to the outer graphene-based sheets for water splitting and proton generation. Driven by electrostatic attraction, protons penetrate through graphene to react with electrons on the inner carbon nitride to generate hydrogen molecule. The produced hydrogen is completely isolated and stored with a high-density level within the sandwich, as no molecules could migrate through graphene. The ability of integrating photocatalytic hydrogen generation and safe capsule storage has made the sandwich system an exciting candidate for realistic solar and hydrogen energy utilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aiming to develop clean and sustainable energy resource, photocatalytic water splitting has gained great interests in both academia and industry communities1,2,3. By harvesting solar light, a photocatalyst generates energetic charges to split water into hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2) molecules1, through which solar power is converted to hydrogen power, a clean and high calorific energy resource. Over years, many promising photocatalysts have been made, such as metal oxides or sulfides4,5,6,7, metal organic frameworks8, pure metals9 and metal-free semiconductors10 and so on. Recently, GR-based non-metallic photocatalysts exhibited advantages in both high performance and low cost11,12,13,14. For instance, g-C3N4, a graphitic carbon nitride, offers good photocatalytic performance together with thermodynamic stability and engineerability11. A recent work using nano-composite photocatalyst of g-C3N4 and carbon nanodot achieved solar energy conversion efficiency of 2.0% for water splitting12.

Unfortunately, the future of widely utilizing hydrogen energy generated from sustainable solar and water resources is hampered by the difficulty of hydrogen collection and storage. Hydrogen generation relies on the delivery of photo-generated electron and hole charges to the photocatalyst reductive and oxidative sites, respectively. To enable energetic carriers driving reactions, the distance between reductive and oxidative sites is limited to the charge migration length (electron mean free path in 10–50 nm). Moreover, protons produced at oxidative sites need to migrate to reductive sites for H2 generation, which also requires short reductive–oxidative distance. However, the short reductive–oxidative distance not only promotes unwanted reverse reactions (recombining proton and –OH/O2 to water) that seriously reduce the efficiency, but also leads to extreme difficulties to collect or store H2 without oxygen contamination. In practice, hydrogen storage is known to be a technical challenge. The mixture of H2 with O2 easily causes dangerous explosion, while metal or carbon fibre containers widely used for H2 storage are expensive. Thus, the practical utilization of photocatalytic water splitting could not be realized until a cost-effective solution is developed to completely isolate hydrogen from oxygen during reactions and safely store H2 afterwards.

Meanwhile, the technique advancements15,16,17 in fabricating large-area GR and GR oxide (GO: GR modified by hydroxyl and epoxy groups) make the capsule of an appreciable amount of H2 feasible. GR-based materials have exhibited excellent hydrogen-adsorption ability with relatively low cost compared with widely used metal materials. For instance, by combining palladium and activated carbon with GR, Lee and colleagues18 achieved high performance in hydrogen storage capacity reaching 0.82 wt% (by weight) at ∼8 MPa (improving nearly 49% compared with pure palladium). Urban and colleagues19 constructed an environmentally stable GO and Mg nanocrystal composite with atomic thickness, which accomplishes hydrogen storage of 6.5 wt%.

Recently, hetero-structures based on two-dimensional (2D) nanosheets have also attracted great attention owing to excellent properties and fabrication feasibility20,21. Xie and colleagues22 constructed a model of GR confined ultrathin tin quantum sheets, achieving high electrochemical activity and excellent stability for carbon dioxide radical anion. As a metal-free system, GR–C3N4 composite layers can effectively harvest visible solar light14. The GR-based materials hold high mobility in delivering charges towards efficient electrochemical and photochemical reactions23,24. Efficient electron–hole separation could be achieved through ultrafast charge transferring between GR–C3N4 layers despite of their weak van der Waals interaction, which has been experimentally observed in vertically stacked transition-metal dichalcogenide heterostructure bilayers with weak van der Waals interaction25,26,27. Moreover, functional groups on GR, including hydroxyl and epoxy, doped heteroatoms, and defects, provide good active sites for water decomposition20,28,29,30,31,32. Our theoretical and experimental works demonstrate that parts of photo-generated electrons in carbon nitrides are collected at nitrogen positions33,34, providing ideal reductive sites for hydrogen generation35. Moreover, Geim, Wu and colleagues36 have demonstrated that GR film is not permeable for any particle larger than proton (or hydrogen atom), and the penetration of proton would be particularly efficient if driven by electrostatic attractions between protons and negative-charged ions.

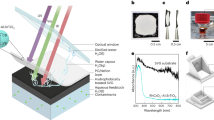

Therefore, we can anticipate that a proper use of all these remarkable properties of GR-based materials can lead to a strategy to utilize the safe storage of hydrogen during the water splitting. For this purpose, here we design a multi-layer structure of CxNy and GR network, where a graphitic carbon nitride (g-CxNy) layer is sandwiched between two GR layers modified by functional groups (GRF). It takes advantage of the high efficiency of GRF–CxNy for photocatalytic water splitting, and the strict mass transport selectivity of GR to achieve safe capsule H2 storage. Based on three known graphitic carbon nitride structures of CN, C2N, C3N4 (Fig. 1a), we build the model sandwich system GRF–CxNy–GRF (Fig. 1b, where g-CN and GO are used as prototype). The water splitting and hydrogen capsuling scheme is illustrated in Fig. 1b: (1) by absorbing visible or ultraviolet light, GO–CxNy generates excitons, which soon separate to energetic electrons and holes. Specifically, electrons on the inner g-CxNy mainly localized on N sites, while holes transfer to two outer GO layers, according to different material properties. (2) The holes on GO attack water molecules adsorbed on GO functional sites, triggering water splitting to produce protons (H+). (3) Driven by electrostatic attractions, protons penetrate through GO to meet electrons on N sites of g-CxNy, and consequently produce H2 molecules. (4) Since H2 cannot transport through GR or GRF (GO), it would be retained in between two GO layers, realizing the purpose of capsule storage. In view of the above processes, a series of related calculations are carried out, including charge separations, chemical reactions, and H2 storages. Our calculation results confirm the rationality and feasibility of integrating hydrogen production and capsule storage into one system. We study the electronic structures and couplings of GR network with g-CxNy in the hybrid structures (Supplementary Fig. 1), to examine their stability, photo-absorption and charge distributions. Reactions of water splitting (oxidative) and hydrogen generation (reductive) are then investigated based on isolated monolayers of GRF sheet and g-CxNy, respectively. Hydrogen storage ability is studied with the GR–CxNy–GR sandwich model.

(a) Models of graphitic carbon nitrides CN, C2N, C3N4. (b) The photocatalytic (water splitting) hydrogen generation and capsule storage scheme: (1) photo-generated electrons (e−) and holes (h+) separating; (2) water splitting to produce protons (H+) through holes (h+) attacking; (3) protons (H+) penetrating through GO and producing H2 molecules; (4) H2 molecules are prohibited from moving out of the sandwich. Here GO–CN–GO is used as an example. Blue, grey, pink and red beads stand for N, C, H (H+) and O atoms, the yellow and light blue clouds are for photo-generated electrons (e−) and holes (h+), and the blue and magenta arrows represent the migration of corresponding particles.

Results

Photo-generated electrons and holes separation

For all optimized sandwich structures, g-CxNy and GR/GO layers exhibit similar interfacial distances of 2.94–3.26 Å and adhesion energies from 1.02 to 3.73 eV (Supplementary Table 1), suggesting good structural stability. The interfacial distance and adhesion energy between g-C3N4 and GR are about 3.09 Å and 1.04 eV, agreeing well with the previous report14. The simulated electronic structures confirmed the semiconductor feature of g-CxNy, which enables photon energy harvesting. The computed dielectric function suggested that bare CN, C2N, C3N4 mainly absorb ultraviolet light (Supplementary Fig. 2), in consistent with their band energy gaps (Supplementary Fig. 3). Their gaps were narrowed by coupling with GR/GO layers (Supplementary Fig. 3)14, enabling the hybrid systems to harvest both visible and ultraviolet photons (Supplementary Fig. 2), and thereby convert the majority of solar power into energized electrons and holes.

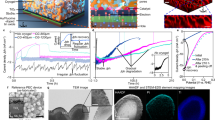

The next key step is to separately deliver photo-generated electrons and holes to reductive and oxidative reaction sites. It is well documented that a difference in work function between different materials could induce electron flowing from the material with lower work function to the one with higher work function37. Here we found that the GR-based material has lower work functions than the CxNy, ranging from 1.7 to 2.91 eV (Supplementary Fig. 4). Therefore, before the photo-excitation, the sandwiched g-CN, C2N and C3N4 unit cells could donate 0.34–0.72, 0.18–0.20 and 0.16–0.25 positive charges (h+) to the outer GR/GO layers, respectively (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 5), exhibiting well-separated electron and hole carrier distributions. We also carried out time dependent ab initio non-adiabatic molecular dynamics (AI-NAMD) simulations to describe the ultrafast hole evolution process. In Supplementary Fig. 6, it is shown that the hole with lower energy (near the valence band) could transfer from CN to GR, and ∼14% hole carriers would reach the GR sheet within 3 ps. While for the hole of higher energy, more than half of the carriers would quickly transfer to the GR sheet within 0.4 ps. Ultimately, above 80% hole carriers in CN layer would transfer to the GR layer within a few ps. Such an ultrafast charge transfer can compete with the electron-hole recombination and ensure the subsequent reactions (that is, water splitting on GO, and H2 generation on CxNy). By adding 1.0 extra electron or hole carrier to the sandwich system, we have modelled the distributions of photo-generated charges. As displayed in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 7 and 8), the outer GR or GO layers always collect hole carriers, whereas inner g-CxNy accumulates electrons. In Table 1, one photo-generated electron carrier induces about 0.68–0.87, 0.33–0.45 and 0.32–0.33 e− in the inner CN, C2N and C3N4 units, respectively. Although the GR/GO cells can collect 1.17–1.59 (with CN), 1.01–1.10 (with C2N) and 1.01–1.23 (with C3N4) h+ if one extra hole was injected, suggesting photo-generated holes on the outer GO layers.

Charge distribution computed as Bader charge differences between GR/GO–CN–GR/GO sandwich with one extra carrier (photo-generated electron (e−) or hole (h+)) and the neutral monolayers of GR/GO and g-CN, from top and side view. Yellow and blue bubbles represent electron and hole charges with isosurface value of 0.0005, e Å−3.

Water splitting driven by photo-induced energetic charges

The water splitting starts with H2O adsorption to the outer GRF surfaces. Functional groups on GR induce polarized charges around active sites, which is helpful for H2O adsorption (Fig. 3a–c). Relatively high adsorption energies were found for water on various GRF materials (Eads in Supplementary Table 2), with 0.32–0.37 eV for GO (Supplementary Fig. 9), 0.60–1.02 eV for GRM (metal: Zn, Cu, Fe, Co, Ni in Supplementary Fig. 10), 0.47 and 0.07 eV for GRSi and GRN (Supplementary Fig. 11), 1.05 eV for GRTiN4 (TiN4 on GR in Supplementary Fig. 12), and 0.20 eV for GRCv (GR with a carbon defect Cv in Supplementary Fig. 13), respectively. Noticeably, it is shown in Fig. 3a–c that functional groups could collect much hole carriers after adsorbing water molecule, making it ready for oxidative reaction. Moreover, these groups effectively reduce the energy barrier (Eb) for water splitting. Based on climbing image nudged elastic band calculations for transition states (Supplementary Figs 9–13), the Eb value of 5.13 eV for bare H2O is decreased to 3.64 eV with the GR catalyst, 3.34–3.56 for the GOOH and GOO catalysts, 0.58–1.09 eV for the GRM (metal: Zn, Cu, Fe, Co), 0.41 eV for the GRSi, 0.86 eV for the GRTiN4 and 0.40 eV for the GRCv (Supplementary Table 2). During photocatalysis, such energy barriers could be easily overcome by GRF receiving photo-induced energetic hole carriers. Similar to GO/GR, GRF with other functional groups tend to extract positive charges from the middle CxNy layer (Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Table 3), validating the feasibility of photo-generated charge separation. The hole injection effectively reduced the Gibbs free energy for water splitting from 1.55 and 2.34 eV at the neutral state to 1.08 and 1.67 eV for the positively charged GOOH and GOO, respectively, favouring water splitting in terms of thermodynamics (Supplementary Table 4).

(a–c) Optimized H2O adsorption geometries and charge distributions (with one photo-generated h+) on GOOH, GOO and GRCo sheets. (d) The computed energy barrier (Eb) of water splitting reaction catalysed by GR or GRF. Here data of pure GR are retrieved from ref. 30, and No-ca. stands for bare water reaction without catalyst. GOOH and GOO represent the hydroxyl and epoxy GO; GRZn, GRCu, GREe, GRCo, GRNi represent the metal-doped GR with Zn, Cu, Fe, Co, Ni atom, respectively; GRSi, GRN stand for Si, N atom-doped GR; GRTiN4 represents TiN4-doped GR and GRCv means for GR with a carbon defect. Yellow and blue bubbles represent electron and hole charges with isosurface value of 0.0005, e Å−3. The observation windows in a–c highlight the local adsorption sites for water molecule.

Protons penetration and hydrogen generation

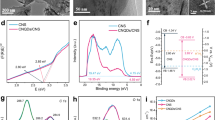

Driven by the electrostatic attraction force, protons produced at the oxidative sites would penetrate through the outer GR-based layers to meet the inner g-CxNy. The electrostatic interaction energy between the proton and the CxNy with photo-generated electrons is 1.48–4.04 eV, which could readily overcome the proton transport barrier in GR of ∼1.23 eV (ref. 36) (Supplementary Table 5). This process is also verified by our ab initio MD simulations for proton transfer through the GR sheet in the GR-C3N4 structure (Supplementary Movie 1, Supplementary Fig. 15), in which parts of photo-generated electrons could be collected by nitrogens. As shown in Fig. 4a, the proton would be chemically bonded with nitrogen. Bader charge analysis found that such N–H bond extracts ∼10% of one photo-generated e− in the whole GR–C3N4–GR unit. The negative charge can attract another approaching proton, which consequently bonds to the previous H to generate a H2 molecule. The g-CxNy desorbs H2 (Fig. 4b) exothermically, with 0.17 eV for neutral structure while 0.25 eV for negative charged one. Geim and colleagues36 have demonstrated that GR network allows only proton to pass through. Therefore, O2 and hydroxyl radicals are kept outside from the inside H2 and protons (attracted by negative charges). These thus suppress the unwanted reverse reaction in water splitting, and realize the complete hydrogen evolution process.

(a–c) Optimized configurations of the GR–C3N4–GR sandwich adsorbed with one H atom, one H2 molecule and many H2 molecules with different interfacial spaces. d in c stands for interfacial distance. (d) The energy costs (ΔE) to achieve different H2 store rate. (e) The variation of the pressure imposed to the outer graphene sheet for GR–C3N4–GR sandwich structure to achieve different H2 store rate. 1 bar=105 Pa (∼1 standard atmospheric pressure).

Capsule hydrogen storage

With sufficient energetic electrons and holes supplies from photo-excited g-CxNy, appreciable amounts of H2 molecules would be produced. As H2 cannot pass through GR-based material, it would be capsuled inside the sandwich. The commercial H2 storage standard postulated by US Department of Energy is 65 kg m−3 (hydrogen storage system per se) and 6.5 wt% (by weight)38. Although pressurization techniques, container ameliorations and extra absorbents could help to reach this goal, large-scale storage and transportation were limited due to high cost, security risk and technique difficulty. While our sandwich structure can safely capsule H2. We have tested the accommodations of different amounts of H2 in the GR–C3N4–GR sandwich (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. 16), by allowing whole structure relaxation. The interfacial distance increases from 3.0 to 5.5 Å with the store rate from zero to 2.5 wt%, and saturates at 5.5–5.9 Å with store rate from 2.5 to 5.2 wt% (Supplementary Fig. 17). The storage causes almost no structure deformations, and requires nearly negligible energy with 0.001–0.012 eV for 0.2–5.23 wt% store rate (Fig. 4d). In the distance range of 3.6–5.9 Å, effective interlayer couplings still exist and thereby enable ultraviolet–vis light-absorption and hole charge transfer (Supplementary Fig. 18 and Supplementary Table 6). These agree with previous experimental reports on effective charge transfer between 2D material with interlayer distance of 6–7 Å (refs 25, 27). Moreover, the use of pressurization can easily maintain high H2 store rate by controlling interfacial distance. We have found that the interfacial distance can be maintained at ∼3.1 Å by imposing a certain amount of pressure to the outer GR sheet (Fig. 4e). For example, the storage rate of 5.2 wt% can be achieved with ∼3.1 Å interfacial distance by adding ∼56 bar (1 bar=105 Pa≈1 atm) external pressure, which is comparable with conditions for other storage systems reported in literature (Supplementary Fig. 19). The rate of 5.2 wt% is close to the standard (6.5 wt%) proposed by US DOE. Although our storage rate is yet to reach the best reported values39, our design holds unique advantages, such as low cost, and the combination of both hydrogen production and generation.

Discussion

In summary, we designed the sandwich structure of one g-CxNy in between two GRF, to achieve efficient solar harvest, charge separation and reverse reaction inhibition for photocatalytic water splitting, and more importantly to integrate simultaneous hydrogen generation and capsule storage in a single system. It harvests visible and ultraviolet light to generate energetic holes and electrons distributing separately on oxidative and reductive sites of GRF and g-CxNy. After water splitting on GRF surface, protons penetrate it through to produce H2 inside the sandwich. By allowing only protons to pass through the outer GR layers, it not only suppresses unwanted reverse reaction, but also capsules H2 products to achieve safe storage. Exploring sp2-carbon sheets (GR, fullerene, carbon-nanotube) to capsule many other promising photocatalysts in the same framework would concrete this sandwich concept and provide better candidates for applications. This would stimulate an alternative way of thinking for water splitting towards realistic solar and hydrogen energy utilizations.

Methods

Structural optimization and analysis

All calculations were performed by the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package at the density functional theory level40. Generalized gradient approximation41, Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerh functional together with projector augmented-wave pseudopotential42 were employed. State-of-the-art hybrid functional (HSE06) was used for band structure, work function and absorption spectrum calculations43. Van der Waals correction was included to account for the nonbonding interaction between GR-based layers and g-CxNy. The kinetic energy cutoff was set to be 400 eV in the plane-wave expansion. The periodic boundary condition was set with a 15 Å vacuum region above the plane of GR sheet. For the supercell structure, the Morkhost pack mesh of K points was 3 × 3 × 1, while that for single cell was 9 × 9 × 1.

Transition state calculations

Climbing image nudged elastic band44 was used for the search of transition states, and these states were validated by the SSW package HOWTOs program45.

Adhesion energy and adsorption energy

The interface adhesion energy was computed with Ead=2EGR/GO+ECxNy−Esandwich, where EGR/GO, ECxNy and Esandwich represent the energies of the GR/GO, g-CxNy and sandwich complex, respectively. The adsorption of water to GRF in neutral system was calculated with Eads=EGRF+EH2O−EH2O@GRF (EGRF, EH2O, EH2O@GRF represent energies of the separated parts and their complex).

AI-NAMD details

As for the AI-NAMD calculations46, we used density functional theory implemented by Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package package to carry out the ab initio molecular dynamics. The temperature was set to be 100 K and a 3.5 ps microcanonical trajectory is generated with a time step of 1 fs.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Yang, L. et al. Combining photocatalytic hydrogen generation and capsule storage in graphene based sandwich structures. Nat. Commun. 8, 16049 doi: 10.1038/ncomms16049 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Fujishima, A. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 238, 37–38 (1972).

Liu, C., Colon, B. C., Ziesack, M., Silver, P. A. & Nocera, D. G. Water splitting–biosynthetic system with CO2 reduction efficiencies exceeding photosynthesis. Science 352, 1210–1213 (2016).

Sambur, J. B. et al. Sub-particle reaction and photocurrent mapping to optimize catalyst-modified photoanodes. Nature 530, 77–80 (2016).

Wang, Q. et al. Scalable water splitting on particulate photocatalyst sheets with a solar-to-hydrogen energy conversion efficiency exceeding 1%. Nat. Mater. 15, 611–615 (2016).

Li, R. G. et al. Achieving overall water splitting using titanium dioxide-based photocatalysts of different phases. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 2377–2382 (2015).

Oshima, T., Lu, D., Ishitani, O. & Maeda, K. Intercalation of highly dispersed metal nanoclusters into a layered metal oxide for photocatalytic overall water splitting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 2698–2702 (2015).

Liu, D. et al. The nature of photocatalytic ‘water splitting’ on silicon nanowires. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 2980–2985 (2015).

Meyer, K., Ranocchiari, M. & Van Bokhoven, J. A. Metal organic frameworks for photo-catalytic water splitting. Energy Environ. Sci 8, 1923–1937 (2015).

Bai, S. et al. Boosting photocatalytic water splitting: interfacial charge polarization in atomically controlled core-shell co-catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 14810–14814 (2015).

Zou, X. X. & Zhang, Y. Noble metal-free hydrogen evolution catalysts for water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 5148–5180 (2015).

Wang, X. C. et al. A metal-free polymeric photocatalyst for hydrogen production from water under visible light. Nat. Mater. 8, 76–80 (2009).

Liu, J. et al. Metal-free efficient photocatalyst for stable visible water splitting via a two-electron pathway. Science 347, 970–974 (2015).

Schwinghammer, K. et al. Crystalline carbon nitride nanosheets for improved visible-light hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 1730–1733 (2014).

Du, A. J. et al. Hybrid graphene and graphitic carbon nitride nanocomposite: gap opening, electron–hole puddle, interfacial charge transfer, and enhanced visible light response. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 4393–4397 (2012).

Li, X. S. et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform graphene films on copper foils. Science 324, 1312–1314 (2009).

Xu, X. Z. et al. Ultrafast growth of single-crystal graphene assisted by a continuous oxygen supply. Nat. Nanotechnol 11, 930–935 (2016).

Zou, Z. Y., Dai, B. Y. & Liu, Z. F. CVD process engineering for designed growth of graphene. Sci. China Chem. 43, 1–17 (2013).

Chen, C. H. et al. Hydrogen storage performance in palladium-doped graphene/carbon composites. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 38, 3681–3688 (2013).

Cho, E. S. et al. Graphene oxide/metal nanocrystal multilaminates as the atomic limit for safe and selective hydrogen storage. Nat. Commun. 7, 10804 (2016).

Deng, D. H. et al. Catalysis with two-dimensional materials and their heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol 11, 218–230 (2016).

Zhang, T. et al. Twinned growth behaviour of two-dimensional materials. Nat. Commun. 7, 13911 (2016).

Lei, F. C. et al. Metallic tin quantum sheets confined in graphene toward high-efficiency CO2 electroreduction. Nat. Commun. 7, 12697 (2016).

Bonaccorso, F. et al. Graphene, related two-dimensional crystals, and hybrid systems for energy conversion and storage. Science 347, 1246501 (2015).

Zhang, N., Yang, M. Q., Liu, S., Sun, Y. & Xu, Y. J. Waltzing with the versatile platform of graphene to synthesize composite photocatalysts. Chem. Rev. 115, 10307–10377 (2015).

Hong, X. et al. Ultrafast charge transfer in atomically thin MoS2/WS2 heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 682–686 (2014).

Lee, C. H. et al. Atomically thin p–n junctions with van der Waals heterointerfaces. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 676–681 (2014).

Zhu, X. Y. et al. Charge transfer excitons at van der Waals interfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 8313–8320 (2015).

Yeh, T. F., Cihlář, J., Chang, C. Y., Cheng, C. & Teng, H. Roles of graphene oxide in photocatalytic water splitting. Mater. Today 16, 78–84 (2013).

Qiu, H. J. et al. Nanoporous graphene with single-atom nickel dopants: an efficient and stable catalyst for electrochemical hydrogen production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 14031–14035 (2015).

Xu, Z. et al. Reversible hydrophobic to hydrophilic transition in graphene via water splitting induced by UV irradiation. Sci. Rep. 4, 6450 (2014).

Liu, L. L., Chen, C. P., Zhao, L. S., Wang, Y. & Wang, X. C. Metal-embedded nitrogen-doped graphene for H2O molecule dissociation. Carbon 115, 773–780 (2017).

Kudo, A. & Miseki, Y. Heterogeneous photocatalyst materials for water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 253–278 (2009).

Li, X. Y., Zhong, W. H., Cui, P., Li, J. & Jiang, J. Design of efficient catalysts with double transition metal atoms on C2N Layer. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 1750–1755 (2016).

Li, X. Y. et al. Graphitic carbon bitride supported single-atom catalysts for efficient oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Commun. 52, 13233–13236 (2016).

Li, Y. R. et al. Implementing metal-to-ligand charge transfer in organic semiconductor for improved visible-bear-infrared photocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 28, 6959–6965 (2016).

Hu, S. et al. Proton transport through one-atom-thick crystals. Nature 516, 227–230 (2014).

Xiang, D. et al. Surface transfer doping induced effective modulation on ambipolar characteristics of few-layer black phosphorus. Nat. Commun. 6, 6485 (2015).

Ariharan, A., Viswanathan, B. & Nandhakumar, V. Hydrogen storage on boron substituted carbon materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 41, 3527–3536 (2016).

He, T., Pachfule, P., Wu, H., Xu, Q. & Chen, P. Hydrogen carriers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16059–16075 (2016).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. J. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Erratum: ‘Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential’ [J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207 (2003)]. J. Chem. Phys. 124, 219906 (2006).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jonsson, H. A. Climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Shang, C., Zhang, X. J. & Liu, Z. P. SSW Package HOWTOs Fudan University (2013).

Akimov, A. V. & Prezhdo, O. V. Advanced capabilities of the PYXAID program: integration schemes, decoherence effects, multiexcitonic states, and field-matter interaction. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 10, 789–804 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the 973 Program (No. 2014CB848900), NSFC (No. 21633006, 21473166, 21421063, 21373190, 11620101003) and CAS (No. XDB01020000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.J. conceived the research, Y.L. and J.J. supervised the project. L.Y., X.L., X.W. and X.J. performed the simulations. L.Y., X.L., G.Z., P.C., J.Z., Y.L. and J.J. analysed the data. L.Y., X.L., G.Z., Y.L. and J.J. co-wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, L., Li, X., Zhang, G. et al. Combining photocatalytic hydrogen generation and capsule storage in graphene based sandwich structures. Nat Commun 8, 16049 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms16049

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms16049

This article is cited by

-

Acrylic Acid-Functionalized Cellulose Diacrylate-Carbon Nanocomposite Thin Film: Preparation, Characterization, and Applications

JOM (2022)

-

Self-Supported Graphene Nanosheet-Based Composites as Binder-Free Electrodes for Advanced Electrochemical Energy Conversion and Storage

Electrochemical Energy Reviews (2022)

-

Interfacial electronic structure engineering on molybdenum sulfide for robust dual-pH hydrogen evolution

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Hydrogen storage in incompletely etched multilayer Ti2CTx at room temperature

Nature Nanotechnology (2021)

-

Two-dimensional Hf2CO2/GaN van der Waals heterostructure for overall water splitting: a density functional theory study

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.