Abstract

Weak perturbations can drive an interacting many-particle system far from its initial equilibrium state if one is able to pump into degrees of freedom approximately protected by conservation laws. This concept has for example been used to realize Bose–Einstein condensates of photons, magnons and excitons. Integrable quantum systems, like the one-dimensional Heisenberg model, are characterized by an infinite set of conservation laws. Here, we develop a theory of weakly driven integrable systems and show that pumping can induce large spin or heat currents even in the presence of integrability breaking perturbations, since it activates local and quasi-local approximate conserved quantities. The resulting steady state is qualitatively captured by a truncated generalized Gibbs ensemble with Lagrange parameters that depend on the structure but not on the overall amplitude of perturbations nor the initial state. We suggest to use spin-chain materials driven by terahertz radiation to realize integrability-based spin and heat pumps.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A simple classical example for a weakly driven system is a well-insulated greenhouse. Due to the approximate conservation of the energy within the greenhouse, even weak sunlight can lead to high temperatures in its interior, which can be computed from the simple rate equation for the energy transfer. Similarly, large spin accumulation can be achieved in systems with approximate spin conservation1. Using approximate conservation of the number of photons, magnons or exciton polaritons, one can use pumping by light to reach densities, which allow for the realization of Bose–Einstein condensates2,3,4. Number-conserving collisions induce a quasi-equilibrium state in these systems, which can be efficiently described by introducing a chemical potential whose value is determined by balancing pumping and decay processes. Related theoretical approaches that describe electron-phonon systems far from equilibrium are so-called two-temperature models5: here one uses that the energy of the electrons and phonons are approximately separately conserved to introduce two different temperatures for the subsystems.

Integrable many-particle systems, like the one-dimensional (1D) fermionic Hubbard model or the XXZ Heisenberg model, are described by an infinite number of (local or quasi-local) conservation laws6,7,8,9,10,11. In closed integrable systems those prevent the equilibration into a simple thermal state, for example, after a sudden change of parameters. Instead the system can be described by a generalized Gibbs ensemble (GGE)12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21

where Ci are the conserved quantities and λi the corresponding Lagrange parameters. It has also been shown experimentally22 that GGEs for a Lieb–Liniger model can provide highly accurate descriptions of interacting bosons in 1D.

Many materials are described with high accuracy by integrable models23, however, weak integrability breaking terms and the coupling to thermal phonons imply that in equilibrium these systems are described by simple thermal states,  , instead of GGEs. The proximity to the integrable point and the presence of approximate conservation laws leads to enhanced spin or heat conductivities (within linear-response theory)24,25,26 and also to a slow relaxation after a quantum quench (via GGE-prethermalization) towards the equilibrium state27.

, instead of GGEs. The proximity to the integrable point and the presence of approximate conservation laws leads to enhanced spin or heat conductivities (within linear-response theory)24,25,26 and also to a slow relaxation after a quantum quench (via GGE-prethermalization) towards the equilibrium state27.

We will show that—as in the greenhouse example, see Fig. 1—such an approximately integrable system can be driven far from its thermal equilibrium by weak perturbations arising, for example, from a driving periodic in time or from coupling to a non-thermal bath. To balance the constant heating due to driving the system has to be weakly open, for example, by coupling to a phonon bath. As we will demonstrate this mechanism can be used for example to create large spin and heat currents. Besides the quasi-1D systems considered by us, also approximately many-body localized systems are characterized by infinitely many approximate conservation laws which may lead to a strong response to driving28,29.

(a) A well-insulated greenhouse exposed to sunshine can heat up significantly since energy within it is approximately conserved. (b) As the heat current in spin-chain materials is approximately conserved even weak terahertz radiation can induce large heat current. Material candidates must have appropriate crystal structure, schematically denoted by dashed lines indicating alternating chemical bonds.

Results

Weakly driven system

We consider an interacting many-body system that is approximately described by Hamiltonian H0 and characterized by a finite or infinite number of (quasi-)local conserved quantities Ci, [H0, Ci]=0, one of them being H0. Energy and other conservations are weakly broken by coupling to thermal or non-thermal baths and/or perturbations periodic in time. For simplicity, we assume periodic boundary conditions and a (discreet) translational invariance. We describe the system with density matrix ρ whose dynamics is governed by the Liouvillian super-operator  ,

,

where  can be split into the dominant unitary Hamiltonian evolution

can be split into the dominant unitary Hamiltonian evolution  and perturbation

and perturbation  of strength

of strength  . We are interested in the limit of small

. We are interested in the limit of small  for t→∞, where a unique (Floquet) steady state ρ∞ is obtained. The general structure of perturbation theory in this case has, for example, been discussed in refs 30, 31, 32. In this limit, ρ∞ can be approximated by

for t→∞, where a unique (Floquet) steady state ρ∞ is obtained. The general structure of perturbation theory in this case has, for example, been discussed in refs 30, 31, 32. In this limit, ρ∞ can be approximated by  with

with  according to equation (2). We assume and later support numerically that ρ0 is approximately described by a GGE, see equation (1).

according to equation (2). We assume and later support numerically that ρ0 is approximately described by a GGE, see equation (1).

Here it is essential to note that—as in the greenhouse example discussed above—the parameters λi are not determined by the initial state but by the form of the weak perturbations  . Our central goal is to compute the λi. We first discuss the case of Lindblad dynamics, where perturbation theory linear in

. Our central goal is to compute the λi. We first discuss the case of Lindblad dynamics, where perturbation theory linear in  can be used, and then focus on Hamiltonian dynamics where we have to consider

can be used, and then focus on Hamiltonian dynamics where we have to consider  2 contributions.

2 contributions.

Markovian perturbation

Within the Markovian approximation one can use the Lindblad form for  (ref. 33). Note that Lindblad dynamics is considered here mainly for pedagogical purposes (formulas are simpler) while no Lindblad approximation is used for the models studied below. The coefficients λi that fix the GGE are determined from the condition that the change of the approximately conserved quantities has to vanish in the steady state

(ref. 33). Note that Lindblad dynamics is considered here mainly for pedagogical purposes (formulas are simpler) while no Lindblad approximation is used for the models studied below. The coefficients λi that fix the GGE are determined from the condition that the change of the approximately conserved quantities has to vanish in the steady state

where we used that  . Relation (3) yields a set of coupled equations for λi, where the number of equations is equal to the number of conserved quantities. We define the super-projector

. Relation (3) yields a set of coupled equations for λi, where the number of equations is equal to the number of conserved quantities. We define the super-projector  onto the tangential space of GGE density matrix,

onto the tangential space of GGE density matrix,

using χii′=−Tr(Ci∂ρ0/∂λi′). Then the conditions for ρ0 can be compactly written as

This equation can also be derived by considering higher order perturbations in  , see Methods for details.

, see Methods for details.

Hamiltonian perturbation

For Hamiltonian dynamics  , where H1 may be a sum of several integrability breaking perturbations. Perturbation theory linear in

, where H1 may be a sum of several integrability breaking perturbations. Perturbation theory linear in  vanishes,

vanishes,  for all λi. Therefore one has to expand to order

for all λi. Therefore one has to expand to order  2 and equation (5) is replaced by

2 and equation (5) is replaced by

Since  ,

,  is not in the kernel of

is not in the kernel of  . For periodic driving this equation has to be interpreted within the Floquet formalism, see Methods.

. For periodic driving this equation has to be interpreted within the Floquet formalism, see Methods.

Model

As discussed in the introduction, our goal is to describe a situation which can be realized experimentally in spin-chain materials driven by lasers operating in the terahertz regime. We assume that spin chains are approximately described by a spin-1/2 XXZ Heisenberg model, possibly in the presence of an external magnetic field B,

The system is driven out of equilibrium by a weak (integrability breaking) time-dependent perturbation

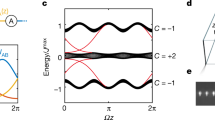

with driving frequency ω. This specific term has been chosen because it can induce heat and spin currents (as can be shown by a symmetry analysis), and because it can be realized experimentally. Such staggered exchange couplings and staggered magnetic fields arise naturally in certain compounds with (at least) two magnetic atoms per unit cell when coupled to uniform electric and magnetic fields, respectively34,35,36,37. See Fig. 1 for a schematic drawing of such a compound and Methods for concrete experimental suggestions. Therefore Hd can be realized by shining a laser (typically at terahertz frequencies) onto the sample. In this case  is proportional to the laser power. Note that for T=0 and B=0 in the adiabatic limit, ω→0, equations (7) and (8) realize an adiabatic Thouless pump, where per pumping cycle one spin is transported by one unit cell38. We will be interested in the opposite regime of large ω and large (effective) temperatures.

is proportional to the laser power. Note that for T=0 and B=0 in the adiabatic limit, ω→0, equations (7) and (8) realize an adiabatic Thouless pump, where per pumping cycle one spin is transported by one unit cell38. We will be interested in the opposite regime of large ω and large (effective) temperatures.

Formally, the periodic perturbation Hd would drive the system to infinite temperature39,40,41,42 (up to remaining conservation laws43, possibly through a prethermal-like regime44). In a solid state experiment this is prohibited by the coupling to phonons and, ultimately, to the thermal environment of the experimental set-up. We mimic this effect by coupling the spin system to a bath of Einstein phonons,  , where dots stand for the couplings to further reservoirs which guarantee that the phonon system is kept at fixed temperature Tph,

, where dots stand for the couplings to further reservoirs which guarantee that the phonon system is kept at fixed temperature Tph,  . See Methods for details on finite size calculation using a broadened distribution of phonon energies. The (weak) coupling to the spin system is described by

. See Methods for details on finite size calculation using a broadened distribution of phonon energies. The (weak) coupling to the spin system is described by

To obtain a unique steady state it is essential to break all symmetries, including the Sz conservation. Relativistic effects which relax Sz are mimicked by γm in our approach. We expect  in materials without heavy elements. For simplicity, we set γm=1 within our numerics as this is found to minimize finite size effects, without a qualitative influence on the results. Besides phonons also other integrability breaking perturbations exist in real materials, including defects, which typically dominate at the lowest temperatures. For high temperatures of the order of J (relevant for the considered set-up) it is realistic to assume that phonon coupling dominates.

in materials without heavy elements. For simplicity, we set γm=1 within our numerics as this is found to minimize finite size effects, without a qualitative influence on the results. Besides phonons also other integrability breaking perturbations exist in real materials, including defects, which typically dominate at the lowest temperatures. For high temperatures of the order of J (relevant for the considered set-up) it is realistic to assume that phonon coupling dominates.

In the presence of a periodic perturbation, equation (8), in the long-time limit the density matrix is changing periodically, ρ(t→∞)=∑ne−iωntρ(n) with  ,

,  . Within the Floquet formalism one therefore promotes the steady-state density matrix to a vector and Liouville operator to a matrix, see Methods. For weak driving,

. Within the Floquet formalism one therefore promotes the steady-state density matrix to a vector and Liouville operator to a matrix, see Methods. For weak driving,  d→0, only the n=0 sector remains and the GGE ansatz, equation (1), simply reads

d→0, only the n=0 sector remains and the GGE ansatz, equation (1), simply reads  , where we included also the phonon density matrix, see above.

, where we included also the phonon density matrix, see above.

Steady state

We will use two different approaches to determine an approximate solution for the steady-state density matrix. First, we will parametrize ρ0, equation (1), with a small number of (quasi-)local conserved quantities, Ci, i=1, …, NC. In an alternative approach, feasible for small systems, we take all conserved quantities into account: local and non-local, commuting and non-commuting. While the second approach is formally exact in the limit  d,

d, ph→0, the first one is, perhaps, more intuitive and can be computed for larger system sizes.

ph→0, the first one is, perhaps, more intuitive and can be computed for larger system sizes.

For the XXZ Heisenberg model an infinite set of mutually commuting local conserved quantities Ci is known, see Methods. C1 is the total spin  and C2=HXXZ. Importantly, C3 is the heat current45 C3=JH(B=0). In addition there also exist (infinite) sets of quasi-local commuting conserved quantities8,9,10. As shown in refs 8, 46 the spin-reversal parity-odd family has an overlap with the spin current JS at Δ<J. Therefore both heat and spin current could show a large response to a weak perturbation. For our analysis, we choose three or five (NC=4, NC=6) most local conserved quantities Ci, i=1, …, NC−1. From the quasi-local sets, we include as a single (effective) operator the conserved part of spin current JSc, computed numerically25,47. For details see Methods. In the presence of an external magnetic field, equation (7), the heat current also has, in addition to C3, a spin current component, JH=C3−BJS (ref. 45).

and C2=HXXZ. Importantly, C3 is the heat current45 C3=JH(B=0). In addition there also exist (infinite) sets of quasi-local commuting conserved quantities8,9,10. As shown in refs 8, 46 the spin-reversal parity-odd family has an overlap with the spin current JS at Δ<J. Therefore both heat and spin current could show a large response to a weak perturbation. For our analysis, we choose three or five (NC=4, NC=6) most local conserved quantities Ci, i=1, …, NC−1. From the quasi-local sets, we include as a single (effective) operator the conserved part of spin current JSc, computed numerically25,47. For details see Methods. In the presence of an external magnetic field, equation (7), the heat current also has, in addition to C3, a spin current component, JH=C3−BJS (ref. 45).

For the visualization of our results it is useful to define generalized forces Fi in the space of Lagrange parameters by rewriting  such that

such that  ,

,

computed using exact diagonalization, see Methods. The vector F is a function of the Lagrange parameters λi, which points into the direction of the steady-state stable fixed point obtained from Fi=0. In the absence of driving (Fig. 2a) one obtains the expected thermal state with T=Tph while all other Lagrange parameters λi vanish. For finite driving the GGE is activated and the λi become finite (Fig. 2b). To obtain the steady state, we solve χ F=0 using Newton’s method.

Effective force F in the space of Lagrange parameters (β, λ3) using  as an ansatz for the generalized Gibbs ensemble. Parameters: J=Δ=−B=ω=ωph=Tph. Lagrange parameters (β, λ3) are plotted in units 1/J and 1/J2, respectively. (a) In the absence of an external driving,

as an ansatz for the generalized Gibbs ensemble. Parameters: J=Δ=−B=ω=ωph=Tph. Lagrange parameters (β, λ3) are plotted in units 1/J and 1/J2, respectively. (a) In the absence of an external driving,  d=0, the stable fixed point (red dot) is given by the thermal ensemble, β=1/Tph, λ3=0. (b) When the system is driven by Hd (

d=0, the stable fixed point (red dot) is given by the thermal ensemble, β=1/Tph, λ3=0. (b) When the system is driven by Hd ( d=

d= ph), it heats up and λ3 becomes finite.

ph), it heats up and λ3 becomes finite.

For the second approach, performed on small N-site systems, we first numerically construct a basis in the set of all (local and non-local) conserved operators,  , where

, where  . Due to degeneracies we find (for finite B and Δ≠J) about 2·2N elements

. Due to degeneracies we find (for finite B and Δ≠J) about 2·2N elements  . In the limit

. In the limit  d,

d,  ph→0 the steady-state density matrix ρ∞ has to fulfil

ph→0 the steady-state density matrix ρ∞ has to fulfil  and therefore can be exactly written as a linear combination of the Qi,

and therefore can be exactly written as a linear combination of the Qi,  . Using equation (6), we therefore find that the steady-state density matrix for

. Using equation (6), we therefore find that the steady-state density matrix for  d,

d,  ph→0 is exactly given by the unique eigenvector with eigenvalue zero of the matrix

ph→0 is exactly given by the unique eigenvector with eigenvalue zero of the matrix

where  are Floquet matrices, see Methods. Note that only the relative

are Floquet matrices, see Methods. Note that only the relative  d/

d/ ph and not the absolute strength of perturbations determine ρ0, as can be seen by dividing the equations χ F=0 or

ph and not the absolute strength of perturbations determine ρ0, as can be seen by dividing the equations χ F=0 or  by

by  .

.

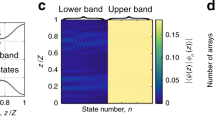

In Fig. 3, we show the expectation value of the energy and of the heat current densities as functions of  d/

d/ ph taking into account NC=4, NC=6, and all conserved quantities. The energy density expectation value is already obtained with good accuracy for NC=4 and even better for NC=6. The heat current vanishes both in thermal equilibrium,

ph taking into account NC=4, NC=6, and all conserved quantities. The energy density expectation value is already obtained with good accuracy for NC=4 and even better for NC=6. The heat current vanishes both in thermal equilibrium,  d→0, and for

d→0, and for  ph→0, where the system is described by an infinite temperature state with finite magnetization,

ph→0, where the system is described by an infinite temperature state with finite magnetization,  and

and  . It takes its largest value for

. It takes its largest value for  . For the currents a description in terms of NC=4 or 6 is qualitatively but not quantitatively accurate. Our study strongly suggests that further quasi-local conserved quantities contribute, as discussed in quench protocols15,16,17, see also ref. 25. For the chosen parameters our results depend only weakly on the system size N, see inset of Fig. 3. System size analysis is performed for NC=6 since the solution based on all conservations cannot be obtained for larger systems.

. For the currents a description in terms of NC=4 or 6 is qualitatively but not quantitatively accurate. Our study strongly suggests that further quasi-local conserved quantities contribute, as discussed in quench protocols15,16,17, see also ref. 25. For the chosen parameters our results depend only weakly on the system size N, see inset of Fig. 3. System size analysis is performed for NC=6 since the solution based on all conservations cannot be obtained for larger systems.

Expectation values of (a) energy and (b) heat current densities for a weakly driven spin chain,  d,

d,  ph→0, as functions of the ratio of driving strength

ph→0, as functions of the ratio of driving strength  d and phonon coupling

d and phonon coupling  ph. Red solid lines: exact result taking into account all 7,969 conservation laws of a system of N=12 sites. (a) For the energy accurate results are already obtained with a GGE ensemble based on NC=4 (dot-dashed lines) or NC=6 (dashed lines) conserved quantities. (b) Also the heat current JH=C3−BJS is qualitatively well described by the GGE ensemble but quantitative deviations are larger. Inset: Finite size analysis for (local) C3 based on GGE ensemble with NC=6 conserved quantities. Parameters: J=1, Δ=0.8, B=−1.0, ω=1.6 ωph, ωph=Tph=1.

ph. Red solid lines: exact result taking into account all 7,969 conservation laws of a system of N=12 sites. (a) For the energy accurate results are already obtained with a GGE ensemble based on NC=4 (dot-dashed lines) or NC=6 (dashed lines) conserved quantities. (b) Also the heat current JH=C3−BJS is qualitatively well described by the GGE ensemble but quantitative deviations are larger. Inset: Finite size analysis for (local) C3 based on GGE ensemble with NC=6 conserved quantities. Parameters: J=1, Δ=0.8, B=−1.0, ω=1.6 ωph, ωph=Tph=1.

Our set-up can also be used to create spin currents. Whilst, by symmetry (bond-centered rotation in real and spin space by π around y axis), a finite external field B is needed to obtain a finite heat current, this is not the case for the spin current. Figure 4 displays the spin current density as a function of  d/

d/ ph for B=0. Qualitatively one obtains a behaviour rather similar to the results for the heat current shown in Fig. 3 with a maximum in the spin current for

ph for B=0. Qualitatively one obtains a behaviour rather similar to the results for the heat current shown in Fig. 3 with a maximum in the spin current for  .

.

The external magnetic field B is a parameter which can easily be tuned experimentally. Figure 5 shows heat and spin current densities as a function of external magnetic field B for  . Note that the sign of the magnetic field determines the sign of the heat current

. Note that the sign of the magnetic field determines the sign of the heat current  . All main features of the B-dependence are semi-quantitatively reproduced by the truncated GGE with NC=6. For very large magnetic fields the convergence to the steady-state fixed point becomes slow as transitions rates connecting sectors with different magnetization are strongly suppressed, see Methods for further details.

. All main features of the B-dependence are semi-quantitatively reproduced by the truncated GGE with NC=6. For very large magnetic fields the convergence to the steady-state fixed point becomes slow as transitions rates connecting sectors with different magnetization are strongly suppressed, see Methods for further details.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that driving approximately integrable systems activates and pumps into approximately conserved quantities. Perhaps the most simple experimental set-up to measure the pumping effect predicted in this work, is to use a terahertz laser that excites a spin-chain material like Cu-benzoate where by symmetry staggered terms of the form (8) are expected34,35. As a consequence of the induced heat currents it is anticipated that the system cools down on one side while it heats upon the other. The direction of the effect can be controlled either by changing the direction of the laser beam or the sign of the external magnetic field B.

For the chosen parameters the spin and heat currents expressed in dimensionless units appear to be rather small, of the order of 10−3. While these values can definitely be increased by tuning parameters, for example the external magnetic field, it is important to note that the currents are actually quite large compared to the typical heat or spin currents obtained in bulk materials. To create a heat current of similar size in a good heat conductor like Cu (assuming  K, 5 Å for the distance of the spin chains, and κCu≈400 Wm−1 K−1) one would need a temperature gradient of several 105 Km−1. Similarly, to create a (transversal) spin current of comparable size in a heavy element like Pt using the spin Hall effect (assuming ρPt≈10 μΩ cm and

K, 5 Å for the distance of the spin chains, and κCu≈400 Wm−1 K−1) one would need a temperature gradient of several 105 Km−1. Similarly, to create a (transversal) spin current of comparable size in a heavy element like Pt using the spin Hall effect (assuming ρPt≈10 μΩ cm and  for the spin Hall angle48) one needs electric fields of the order of 104 V m−1 or sizable current densities of the order of 1011 Am−2. These numbers are even more remarkable when one takes into account that the electron densities in Cu or Pt are at least an order of magnitude higher than the spin density for spin chains with a distance of 5 Å.

for the spin Hall angle48) one needs electric fields of the order of 104 V m−1 or sizable current densities of the order of 1011 Am−2. These numbers are even more remarkable when one takes into account that the electron densities in Cu or Pt are at least an order of magnitude higher than the spin density for spin chains with a distance of 5 Å.

While our study has focused on the steady state, it is instructive to discuss the relevant timescales for its buildup. For this argument, we consider a quench where at time t=0 an initial state is perturbed both by the integrable part of the Hamiltonian and by small non-integrable perturbations. At short times of the order of several 1/J the initial state will prethermalize27,49,50,51,52 into a GGE, where the values of the conserved quantities,  , are set by the initial conditions (with small corrections from the perturbations52,53). Further time evolution can be approximately described by a GGE with time-dependent Lagrange parameters. Their time-dependence is determined by perturbations which assert forces

, are set by the initial conditions (with small corrections from the perturbations52,53). Further time evolution can be approximately described by a GGE with time-dependent Lagrange parameters. Their time-dependence is determined by perturbations which assert forces  , such that dλi/dt≈Fi. Governed by the perturbations the system will loose the memory of its initial condition on a timescale of order 1/

, such that dλi/dt≈Fi. Governed by the perturbations the system will loose the memory of its initial condition on a timescale of order 1/ 2 and relax to the steady state (obtained from Fi=0) which is, in general, completely unrelated to the prethermalized state. Note that the same approach predicts ordinary thermalization in the absence of external driving.

2 and relax to the steady state (obtained from Fi=0) which is, in general, completely unrelated to the prethermalized state. Note that the same approach predicts ordinary thermalization in the absence of external driving.

Our results suggest that the concept of generalized GGEs has a much broader range of application than previously anticipated, now extended to open systems where symmetries are not exact and integrability is weakly broken. A truncated GGE proved to be useful for qualitative description, however, it showed quantitative discrepancies most probably due to disregarded quasi-local conserved quantities, as observed already in quench protocols15,16. We are planning a future study tailored to address this issue systematically. It would be interesting to develop integrability-based methods similar to the quench-action approach15,16,54,55 to treat such situations.

Most important for applications is that the integrability is not required to be realized exactly but only approximately. Efficient pumping requires only that the pumping rates are of the same order of magnitude as the loss rates arising from integrability breaking terms. Especially the integrability-based creation of large spin currents could find its application in future spintronics devices.

Methods

Perturbing around ρ0

The central equations (5) or (6), used to determine the density matrix ρ0 in the limit  →0, have to be consistent and can also even be derived by considering perturbations around ρ0, ρ∞=ρ0+δρ.

→0, have to be consistent and can also even be derived by considering perturbations around ρ0, ρ∞=ρ0+δρ.

First, the leading δρ correction to  , equation (3), arising from

, equation (3), arising from  which is nominally of the same order as

which is nominally of the same order as  vanishes trivially as Tr(Ci[H0, δρ])=Tr(δρ[Ci, H0])=0.

vanishes trivially as Tr(Ci[H0, δρ])=Tr(δρ[Ci, H0])=0.

For arbitrary ρ0, δρ is exactly given by  , where

, where  is a short-hand notation for

is a short-hand notation for  with the infinitesimal regularizer η. The correct expansion point ρ0 is found if

with the infinitesimal regularizer η. The correct expansion point ρ0 is found if  . Below we show that for the projection operator

. Below we show that for the projection operator  , equation (4),

, equation (4),

which would yield  . This contradicts our perturbative approach unless

. This contradicts our perturbative approach unless  , as set by our condition equation (5).

, as set by our condition equation (5).

Equation (12) is a consequence of the fact that  projects onto the tangential space to GGE density matrix. In this space

projects onto the tangential space to GGE density matrix. In this space  vanishes by definition,

vanishes by definition,  , and

, and  is therefore of order

is therefore of order  . Technically, this can be seen by using the general relation

. Technically, this can be seen by using the general relation

for

with  and

and  . Then

. Then

The second term is O(1) as  and therefore

and therefore  . The divergence of

. The divergence of  for

for  →0 can be directly related to the fact that integrable systems are characterized by infinite conductivities (finite Drude weights) at finite temperatures56 as can, for example, be seen24 within the memory matrix formalism57.

→0 can be directly related to the fact that integrable systems are characterized by infinite conductivities (finite Drude weights) at finite temperatures56 as can, for example, be seen24 within the memory matrix formalism57.

All arguments given above can be generalized to situations where leading corrections arise from second-order perturbation theory in which case one obtains equation (6) instead of equation (5).

Staggered hopping and magnetic field modulation

Sizable staggered g-tensors leading to staggered B-fields have been observed in a number of different compounds34,35,36,37. Similarly an external electric field will distort the crystalline structure in these materials, leading to staggered exchange couplings linear in homogeneous electric fields. An example of such a material is Cu-benzoate34 with the above modulations allowed by symmetry for electric (magnetic) fields applied in the 010 (001) crystallographic direction. In this system the staggered g-tensor has been measured to be ∼0.08 (ref. 35), the size of the staggered exchange coupling is unknown. For simplicity, we assume in equation (8) that the two staggered terms are of the same size.

Conservation laws of the XXZ Heisenberg model

An infinite set of local conserved quantities Ci of the Heisenberg model HXXZ=H0(B=0) can be obtained using the boost operator  (where HXXZ=∑j hj,j+1) from the recursion relation [Ob, Ci]=Ci+1 for i>1 with

(where HXXZ=∑j hj,j+1) from the recursion relation [Ob, Ci]=Ci+1 for i>1 with  , C2=HXXZ (ref. 7). In general, Ci are operators involving maximally i neighbouring sites. Importantly, C3 in the absence of external magnetic field equals the heat current

, C2=HXXZ (ref. 7). In general, Ci are operators involving maximally i neighbouring sites. Importantly, C3 in the absence of external magnetic field equals the heat current

with rescaled spin operators  for λz=Δ/J, λx=λy=1. In the presence of external magnetic field, equation (7), heat current has in addition to C3 also a spin current component,

for λz=Δ/J, λx=λy=1. In the presence of external magnetic field, equation (7), heat current has in addition to C3 also a spin current component,

As understood recently there also exist families of quasi-local conserved quantities8,9,10, which are mostly disregarded in our study with the exception of a spin-reversal parity-odd operator, JSc. The latter is constructed as the conserved part of the spin current operator JS,

where  are simultaneous eigenstates of the Ci. Since it is known that the spin current has an overlap with the quasi-local family45 for Δ<J, the conserved JSc contains quasi-local components (and, possibly, non-local components not contributing in the thermodynamic limit).

are simultaneous eigenstates of the Ci. Since it is known that the spin current has an overlap with the quasi-local family45 for Δ<J, the conserved JSc contains quasi-local components (and, possibly, non-local components not contributing in the thermodynamic limit).

Floquet formulation

For a periodically driven system described by  with

with  the density matrix changes periodically in the long-time limit. Therefore it is useful to split it into Floquet components,

the density matrix changes periodically in the long-time limit. Therefore it is useful to split it into Floquet components,

with  and ω=2π/T. The Floquet components are combined into the vector

and ω=2π/T. The Floquet components are combined into the vector  . The Liouvillian is promoted to a (static) matrix

. The Liouvillian is promoted to a (static) matrix  with

with  . Using this notation, all results obtained for static Liouvillian super-operators directly translate to the time-periodic case. Within our set-up H0, all approximate conservation laws Ci and the GGE density matrix ρ0 are static and therefore the projection operator

. Using this notation, all results obtained for static Liouvillian super-operators directly translate to the time-periodic case. Within our set-up H0, all approximate conservation laws Ci and the GGE density matrix ρ0 are static and therefore the projection operator  , equation (4), projects onto the n=0 Floquet sector only. The steady-state condition, equation (6), thus means that the approximately conserved quantities do not grow after averaging over an oscillation period. To second order in

, equation (4), projects onto the n=0 Floquet sector only. The steady-state condition, equation (6), thus means that the approximately conserved quantities do not grow after averaging over an oscillation period. To second order in  d only transitions from the n=0 to the n=±1 Floquet sector and back contribute to equations (6) or (10), as

d only transitions from the n=0 to the n=±1 Floquet sector and back contribute to equations (6) or (10), as  for

for  .

.

For the generalized force due to the periodic driving, we obtain from (10)

where we used H0 eigenstates  with

with  , matrix elements

, matrix elements  ,

,  , and the notation

, and the notation  . Note that equation (20) contains—as expected—transition rates well-known from Fermi’s golden rule. Equation (20) is evaluated for finite systems of size N by replacing the δ function by a Lorentzian (1/π)η/(ω2+η2) (η=0.1J for N=12).

. Note that equation (20) contains—as expected—transition rates well-known from Fermi’s golden rule. Equation (20) is evaluated for finite systems of size N by replacing the δ function by a Lorentzian (1/π)η/(ω2+η2) (η=0.1J for N=12).

Equation (20) is only valid for situations where all conservation laws commute with each other, with  , see below for a brief discussion of the non-commuting case.

, see below for a brief discussion of the non-commuting case.

Phonon coupling

As written in the main text, we assume that the phonon system always remains at equilibrium,  . Using equation (10), after tracing over phonons, we obtain for the generalized force

. Using equation (10), after tracing over phonons, we obtain for the generalized force

where  is the equilibrium Bose distribution evaluated at the temperature Tph and A(ph)(ω) is the phonon spectral function. For our finite size calculation, we broaden the spectral function of the Einstein phonons using

is the equilibrium Bose distribution evaluated at the temperature Tph and A(ph)(ω) is the phonon spectral function. For our finite size calculation, we broaden the spectral function of the Einstein phonons using  . This choice of broadening ensures detailed balance relations (necessary to obtain a thermal state in the absence of driving) and the positivity of phonon frequencies (necessary for stability). For all plots we use η=0.4J. However, we have checked that similar results are obtained, for example, for η=0.1J for magnetic fields up to

. This choice of broadening ensures detailed balance relations (necessary to obtain a thermal state in the absence of driving) and the positivity of phonon frequencies (necessary for stability). For all plots we use η=0.4J. However, we have checked that similar results are obtained, for example, for η=0.1J for magnetic fields up to  =2J. For larger fields η=0.1J does not provide a sufficient amount of relaxation between sectors with different magnetization and convergence becomes slow and unstable. For η=0.4J larger fields,

=2J. For larger fields η=0.1J does not provide a sufficient amount of relaxation between sectors with different magnetization and convergence becomes slow and unstable. For η=0.4J larger fields,  ≲5J, can be reached.

≲5J, can be reached.

Implementation of non-commuting conservation laws

As discussed in the main text, a complete basis of all non-local commuting or non-commuting conserved quantities is given by  which solve the equation

which solve the equation  for

for  . Using the exact eigenstates of H0 it is straightforward to evaluate equation (11), where we use for our finite size calculations the broadening procedures described above. As a technical detail, we note that, when one follows this procedure, one has to evaluate in the phonon sectors integrals of the type

. Using the exact eigenstates of H0 it is straightforward to evaluate equation (11), where we use for our finite size calculations the broadening procedures described above. As a technical detail, we note that, when one follows this procedure, one has to evaluate in the phonon sectors integrals of the type  numerically. For efficient evaluations, we use interpolating functions for these integrals.

numerically. For efficient evaluations, we use interpolating functions for these integrals.

GGE estimation for other conserved quantities

To provide further support for our claim that truncated GGEs give a semi-quantitative description of our weakly open system we show in Fig. 6 additional comparison of the  and

and  as a function of magnetic field B at

as a function of magnetic field B at  , comparing as in the main text the exact calculation including all conserved quantities and the truncated GGE with NC=6 (quasi-)local conserved quantities. The GGE ansatz captures the right magnitude and the correct behaviour in the dependence on B also for more complicated 4-spin operators like C4. We use same parameters as for the Fig. 5 in the main text:

, comparing as in the main text the exact calculation including all conserved quantities and the truncated GGE with NC=6 (quasi-)local conserved quantities. The GGE ansatz captures the right magnitude and the correct behaviour in the dependence on B also for more complicated 4-spin operators like C4. We use same parameters as for the Fig. 5 in the main text:  , J=1, Δ=0.8, ω=1.6 ωph, ωph=Tph=1, N=12.

, J=1, Δ=0.8, ω=1.6 ωph, ωph=Tph=1, N=12.

Code availability

Custom computer codes used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Documentation of the codes is not available.

Data availability

Data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Lange, F. et al. Pumping approximately integrable systems. Nat. Commun. 8, 15767 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15767 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Kikkawa, J. M. & Awschalom, D. D. Resonant spin amplification in n-type GaAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 4313–4316 (1998).

Klaers, J., Schmitt, J., Vewinger, F. & Weitz, M. Bose-Einstein condensation of photons in an optical microcavity. Nature 468, 545–548 (2010).

Demokritov, S. et al. Bose-Einstein condensation of quasi-equilibrium magnons at room temperature under pumping. Nature 443, 430–433 (2006).

Kasprzak, J. et al. Bose-Einstein condensation of exciton polaritons. Nature 443, 409–414 (2006).

Allen, P. B. Theory of thermal relaxation of electrons in metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 1460–1463 (1987).

Faddeev, L. Algebraic aspects of the Bethe ansatz. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 10, 1845–1878 (1995).

Grabowski, M. P. & Mathieu, P. Structure of the conservation laws in integrable spin chains with short range interactions. Ann. Phys. 243, 299–371 (1995).

Prosen, T. & Ilievski, E. Families of quasilocal conservation laws and quantum spin transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 057203 (2013).

Mierzejewski, M., Prelovšek, P. & Prosen, T. Identifying local and quasilocal conserved quantities in integrable systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 140601 (2015).

Ilievski, E., Medenjak, M. & Prosen, T. Quasilocal conserved operators in the isotropic Heisenberg spin-1/2 chain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 120601 (2015).

Ilievski, E., Medenjak, M., Prosen, T. & Zadnik, L. Quasilocal charges in integrable lattice systems. J. Stat. Mech.: Theory Exp. 2016, 064008 (2016).

Rigol, M., Dunjko, V., Yurovsky, V. & Olshanii, M. Relaxation in a completely integrable many-body quantum system: an ab initio study of the dynamics of the highly excited states of 1d lattice hard-core bosons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 050405 (2007).

Pozsgay, B. The generalized Gibbs ensemble for Heisenberg spin chains. J. Stat. Mech.: Theory Exp. 2013, P07003 (2013).

Fagotti, M. & Essler, F. H. Stationary behaviour of observables after a quantum quench in the spin-1/2 Heisenberg XXZ chain. J. Stat. Mech.: Theory Exp. 2013, P07012 (2013).

Wouters, B. et al. Quenching the anisotropic Heisenberg chain: exact solution and generalized Gibbs ensemble predictions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 117202 (2014).

Pozsgay, B. et al. Correlations after quantum quenches in the XXZ spin chain: Failure of the generalized Gibbs ensemble. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 117203 (2014).

Ilievski, E. et al. Complete generalized Gibbs ensembles in an interacting theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 157201 (2015).

Vidmar, L. & Rigol, M. Generalized Gibbs ensemble in integrable lattice models. J. Stat. Mech.: Theory Exp. 2016, 064007 (2016).

Essler, F. H. L. & Fagotti, M. Quench dynamics and relaxation in isolated integrable quantum spin chains. J. Stat. Mech.: Theory Exp. 2016, 064002 (2016).

Ilievski, E., Quinn, E. & Caux, J.-S. From interacting particles to equilibrium statistical ensembles. Phys. Rev. B 95, 115128 (2017).

De Luca, A., Collura, M. & De Nardis, J. Non-equilibrium spin transport in the XXZ chain: steady spin currents and emergence of magnetic domains. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1612.07265 (2016).

Langen, T. et al. Experimental observation of a generalized Gibbs ensemble. Science 348, 207–211 (2015).

Mourigal, M. et al. Fractional spinon excitations in the quantum Heisenberg antiferromagnetic chain. Nat. Phys. 9, 435–441 (2013).

Jung, P., Helmes, R. W. & Rosch, A. Transport in almost integrable models: Perturbed Heisenberg chains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 067202 (2006).

Jung, P. & Rosch, A. Spin conductivity in almost integrable spin chains. Phys. Rev. B 76, 245108 (2007).

Jung, P. & Rosch, A. Lower bounds for the conductivities of correlated quantum systems. Phys. Rev. B 75, 245104 (2007).

Bertini, B., Essler, F. H. L., Groha, S. & Robinson, N. J. Prethermalization and thermalization in models with weak integrability breaking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 180601 (2015).

De Luca, A. & Rosso, A. Dynamic nuclear polarization and the paradox of quantum thermalization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 080401 (2015).

De Luca, A., Rodrguez-Arias, I., Müller, M. & Rosso, A. Thermalization and many-body localization in systems under dynamic nuclear polarization. Phys. Rev. B 94, 014203 (2016).

Cirac, J. I., Blatt, R., Zoller, P. & Phillips, W. D. Laser cooling of trapped ions in a standing wave. Phys. Rev. A 46, 2668–2681 (1992).

Benatti, F., Nagy, A. & Narnhofer, H. Asymptotic entanglement and Lindblad dynamics: a perturbative approach. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 44, 155303 (2011).

Li, A. C. Y., Petruccione, F. & Koch, J. Perturbative approach to Markovian open quantum systems. Sci. Rep. 4, 4887 (2014).

Petruccione, F. & Breuer, H.-P. The Theory of Open Quantum Systems Oxford Univ. Press (2002).

Affleck, I. & Oshikawa, M. Field-induced gap in Cu benzoate and other s=(1)/(2) antiferromagnetic chains. Phys. Rev. B 60, 1038–1056 (1999).

Nojiri, H., Ajiro, Y., Asano, T. & Boucher, J. Magnetic excitation of s=1/2 antiferromagnetic spin chain Cu benzoate in high magnetic fields. New J. Phys. 8, 218 (2006).

Kimura, S. et al. Collapse of magnetic order of the quasi one-dimensional ising-like antiferromagnet BaCo2V2O8 in transverse fields. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 82, 033706 (2013).

Niesen, S. K. et al. Substitution effects on the temperature versus magnetic field phase diagrams of the quasi-one-dimensional effective Ising spin-(1)/(2) chain system BaCo2V2O8 . Phys. Rev. B 90, 104419 (2014).

Shindou, R. Quantum spin pump in s=1/2 antiferromagnetic chains-holonomy of phase operators in sine-Gordon theory-. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 74, 1214–1223 (2005).

Genske, M. & Rosch, A. Floquet-Boltzmann equation for periodically driven Fermi systems. Phys. Rev. A 92, 062108 (2015).

D’Alessio, L. & Rigol, M. Long-time behavior of isolated periodically driven interacting lattice systems. Phys. Rev. X 4, 041048 (2014).

Lazarides, A., Das, A. & Moessner, R. Equilibrium states of generic quantum systems subject to periodic driving. Phys. Rev. E 90, 012110 (2014).

Ponte, P., Chandran, A., Papić, Z. & Abanin, D. A. Periodically driven ergodic and many-body localized quantum systems. Ann. Phys. 353, 196–204 (2015).

Lazarides, A., Das, A. & Moessner, R. Periodic thermodynamics of isolated quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 150401 (2014).

Canovi, E., Kollar, M. & Eckstein, M. Stroboscopic prethermalization in weakly interacting periodically driven systems. Phys. Rev. E 93, 012130 (2016).

Zotos, X., Naef, F. & Prelovšek, P. Transport and conservation laws. Phys. Rev. B 55, 11029–11032 (1997).

Prosen, T. Open XXZ spin chain: nonequilibrium steady state and a strict bound on ballistic transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 217206 (2011).

Mierzejewski, M., Prelovšek, P. & Prosen, T. Breakdown of the generalized Gibbs ensemble for current-generating quenches. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 020602 (2014).

Sinova, J., Valenzuela, S. O., Wunderlich, J., Back, C. H. & Jungwirth, T. Spin hall effects. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 1213–1260 (2015).

Berges, J., Borsányi, S. & Wetterich, C. Prethermalization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 142002 (2004).

Moeckel, M. & Kehrein, S. Interaction quench in the hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 175702 (2008).

Kollar, M., Wolf, F. A. & Eckstein, M. Generalized Gibbs ensemble prediction of prethermalization plateaus and their relation to nonthermal steady states in integrable systems. Phys. Rev. B 84, 054304 (2011).

Essler, F. H. L., Kehrein, S., Manmana, S. R. & Robinson, N. J. Quench dynamics in a model with tuneable integrability breaking. Phys. Rev. B 89, 165104 (2014).

Mierzejewski, M., Prosen, T. & Prelovšek, P. Approximate conservation laws in perturbed integrable lattice models. Phys. Rev. B 92, 195121 (2015).

Caux, J.-S. & Essler, F. H. L. Time evolution of local observables after quenching to an integrable model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 257203 (2013).

Caux, J.-S. The quench action. J. Stat. Mech.: Theory Exp. 2016, 064006 (2016).

Zotos, X. Finite temperature Drude weight of the one-dimensional spin- 1/2 Heisenberg model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 1764–1767 (1999).

Forster, D. Hydrodynamic Fluctuations, Broken Symmetry, and Correlation Functions Benjamin (1975).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge useful discussions with S. Diehl, F.H.L. Essler, M. Fagotti, E. Ilievski, M. Mierzejewski, J. De Nardis, T. Prosen and M.C. Rudner, H.F. Legg for reading the manuscript, and financial support of the German Science Foundation under CRC 1238 (project C04) and CRC TR 183 (project A01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R. and Z.L. designed the study, Z.L. and F.L. performed analytical calculations and F.L. implemented the numerical codes, all authors analysed the results and contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lange, F., Lenarčič, Z. & Rosch, A. Pumping approximately integrable systems. Nat Commun 8, 15767 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15767

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15767

This article is cited by

-

Exploring nonequilibrium phases of photo-doped Mott insulators with generalized Gibbs ensembles

Communications Physics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

d/

d/ ph. The expectation value of spin current density is again maximal for

ph. The expectation value of spin current density is again maximal for  d/

d/ ph≈1. Parameters: J=1, Δ=0.8, ω=1.6 ωph,ωph=Tph=1, N=12.

ph≈1. Parameters: J=1, Δ=0.8, ω=1.6 ωph,ωph=Tph=1, N=12.

, J=1, Δ=0.8, ω=1.6 ωph, ωph=Tph=1, N=12.

, J=1, Δ=0.8, ω=1.6 ωph, ωph=Tph=1, N=12.