Abstract

Hard X-ray lens-less microscopy raises hopes for a non-invasive quantitative imaging, capable of achieving the extreme resolving power demands of nanoscience. However, a limit imposed by the partial coherence of third generation synchrotron sources restricts the sample size to the micrometer range. Recently, X-ray ptychography has been demonstrated as a solution for arbitrarily extending the field of view without degrading the resolution. Here we show that ptychography, applied in the Bragg geometry, opens new perspectives for crystalline imaging. The spatial dependence of the three-dimensional Bragg peak intensity is mapped and the entire data subsequently inverted with a Bragg-adapted phase retrieval ptychographical algorithm. We report on the image obtained from an extended crystalline sample, nanostructured from a silicon-on-insulator substrate. The possibility to retrieve, without transverse size restriction, the highly resolved three-dimensional density and displacement field will allow for the unprecedented investigation of a wide variety of crystalline materials, ranging from life science to microelectronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantitative imaging of strains, dislocations, inclusions and so on becomes in reach with the advances of X-ray coherent diffraction imaging1. The last makes use of the far-field intensity pattern produced by a crystal, illuminated by a plane-wave in Bragg conditions. The phase retrieval is ensured by the oversampling condition, which imposes a finite sample size2. The inversion is performed with iterative algorithms, based on back-and-forth propagations of the wavefield from the sample to the detector plane (see ref. 3 and references therein). However, its development encounters two main limits. For weak displacement fields where small phase shifts in the exit wave-field are expected (for example, owing to surface strain), the obtained reconstruction does not allow the discrimination between illumination wavefront inhomogeneities and crystal displacement fields4. The opposite case of highly heterogeneous strain fields, present in a wide variety of materials (epitaxial and/or embedded nanocrystals, poly-crystalline materials, and so on), is also problematic: investigations are prohibited by the extremely slow convergence of the inversion procedure5,6,7. Bragg ptychography can overcome these limits: it is expected to enable the simultaneous recovering of the sample and illumination functions and its robustness, with regard to strain inhomogeneity, is evidenced from numerical analysis8.

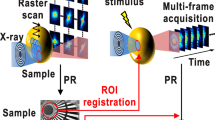

Ptychography, originally proposed for electron microscopy applications9, makes use of multiple exposures that combine redundant information from partially overlapping illumination areas onto an extended sample10. A set of far-field coherent intensity patterns is recorded while the sample is moved through the finite-sized beam spot. The redundancy, resulting from the overlapping condition is the key of the iterative process convergence11. It releases the need for an intensity oversampling condition, opening the field of X-ray lens-less microscopy to samples larger than the transverse coherence lengths of the beam12,13,14,15,16. Recently, the ptychographical iterative engine (PIE) has been proposed17 and further extended18,19 to retrieve simultaneously the sample scattering contrast and the illumination function.

Combining ptychography with Bragg diffraction is highly desirable for crystalline imaging. Moreover, Bragg geometry offers a major advantage for ptychography. A small angular exploration along the rocking curve in the vicinity of the chosen Bragg reflection corresponds to a translation of the wave-vector transfer across the Bragg peak. In practice, full three-dimensional (3D) intensity patterns can be recorded within small angular movements of less than a degree20: the illumination volume can be considered as constant along the rocking curve. Hence, instead of handling the two-dimensional (2D) wave-fields for each illumination position and each tomographic angle14, Bragg ptychography allows dealing directly with the full 3D intensity patterns, for each illumination position only. This approach drastically reduces computational efforts.

Here we report on the experimental demonstration of Bragg ptychography imaging. To this aim, we have designed an extended crystalline nanostructure from a silicon-on-insulator substrate. The finite-sized coherent beam spot required for the measurement was produced by the coherent illumination of a Fresnel zone plate (FZP)21. The 3D Bragg diffraction intensity was measured in the vicinity of the chosen Bragg reflection, as a function of the beam position on the sample. The step size was small enough to ensure the needed high redundancy in the data set. The sample-scattering contrast and the illumination function were simultaneously retrieved from the whole set of intensity data, using a Bragg adapted PIE8. The retrieved features exhibited by the 3D crystalline density and displacement field are discussed below. We expect that this technique, that enables new insights of crystalline nanostructures, will have a key role in materials science.

Results

X-ray bragg ptychography experimental set-up

Figure 1a shows the schematic layout of the experimental X-ray Bragg ptychography set-up. The finite-sized beam spot needed for the ptychography scan results from the focalization of a fully coherent monochromatic beam using a FZP22. For this purpose, the FZP aperture is reduced so that the illumination area matches the beam transverse coherence lengths23. As the FZP central part is occluded by a beam stop to avoid direct beam contribution, the aperture is shifted laterally. The sample is oriented in Bragg condition with its surface normal lying in the vertical plane and inclined with respect to the incident beam. The 3D coherent intensity pattern is measured along the rocking curve (Fig. 1b) at each beam translation tx. The 3D acquisition is repeated while the sample is moved along the horizontal direction, across the beam. The chosen translation step is about 300 nm. According to our observations with limited FZP aperture, the spot-size full-width-at-half-maximum of the field at the focus should be about 200×600 nm2, along the vertical and horizontal directions, respectively. The Bragg geometry induces a further increase of the beam footprint on the sample, to about 500×600 nm2 along the beam and in horizontal direction, respectively. Hence, an overlapping of at least 50% is ensured along the scanning direction. With this set-up, a total of about 108 photons per second is expected at the focus.

(a) X-ray Bragg ptychography set-up including the FZP and its slit-defining aperture, the sample stage and the far-field 2D detector (The FZP central stop and the order sorting aperture have been omitted for clarity). The direct space frame (x, y, z) is chosen in the sample frame. (b) Sketch of the 3D intensity acquisition in Bragg geometry and the associated reciprocal space vectors q1, q2 and q3. (c) Scanning electron micrograph of the lines patterned on the Silicon-on-insulator substrate (Scale bar: 10 μm). The zoomed region (inset) emphasizes the area investigated during the ptychography scan. The translation direction tx is shown together with the two first illumination areas (white ellipses). (d) The same region as seen by atomic force microscopy.

Sample description

The sample, patterned from a Silicon-insulator wafer is composed of two Si <〈110〉 lines of about 40 nm height and of 520 and 260 nm width, respectively. The separation between the lines results in an edge-to-edge distance of 1.7 μm. The line length is about 30 μm, much larger than the beam footprint. Figure 1c,d shows direct characterizations of the sample. The areas delimited by the white ellipses correspond to the first positions of the beam during the scan.

Data analysis

The different crystalline orientation of the sample substrate ensures that the chosen symmetric 220 Bragg reflection arises from the diffraction by the lines only. In Figure 2a, the integrated intensity is plotted as a function of tx. The two maxima correspond to the scattering signals of the two lines. Figure 2b–g shows typical detector frames taken at different tx values and different reciprocal space positions. Interference fringes are observed along the direction perpendicular to the lines. Their frequency, related to the inverse line width, varies with tx. The visibility contrast is estimated to about 70%. The continuity and reproducibility of the observed features give a strong evidence of the absence of beam drift or radiation damage. From these data, one notices two interesting features. (1) The simultaneous presence of interferences with high and low frequencies, which result from the scattering by the large and small Si lines, is an evidence of the simultaneous illumination of the two lines. It is a consequence of a beam spot broader than expected. This is further confirmed by the integrated intensity profile of Figure 2a, where the line-related maxima are much larger than the line widths, as a result of the convolution with the beam. (2) More surprising, a split in the Bragg peak along the Bragg vector direction is observed, which leads to a double peak (labelled p1 and p2 in Figure 2e). Figure 2h allows a further characterization of the peak splitting from the calculation of the splitting intensity contrast, whose behaviour as a function of tx clearly shows that the splitting is associated to the large line only. Peak splitting is an usual signature for phase shift in crystal. Final explanations about these features (beam width and Bragg peak splitting) will arise from the Bragg ptychography reconstructions.

(a) Integrated intensity values as a function of the beam translation tx: the two maxima correspond to the two Si lines, which are schematically indicated (grey rectangles). The line is a guide to the eye. (b–g) 2D coherent intensity patterns measured at the Si 220 reflection for different q3 values (indicated on the graphs) and different positions of the focused beam onto the double line crystalline sample. The corresponding tx values are indicated in (a). A splitting of the Bragg peak is observed along q1, emphasized in (e) by the white arrows and the respective peak labels, p1 and p2. The intensity colour scale is logarithmic. The intensity has been multiplied by 6 in (d,e) and by 25 in (f,g), for clarity. The reciprocal space scale is indicated in the figures where |q1|=|q2|=5×107 m−1. (h) Splitting contrast Cs=1−(Imin/Ip) as a function of q3 and tx: Imin is the mean intensity value at the peak splitting minimum and Ip is the mean intensity at the p1 and p2 positions. Therefore, Cs=1 corresponds to a full splitting. In (h), the abrupt change along tx evidences that the Bragg splitting is linked to the sample structure and occurs preferentially at the large line position. The corresponding colour scale is given on the right. The scale is |q3|=2.2×107 m−1.

3D reconstruction of the crystalline scattering contrast

The whole 3D intensity set is analysed with our Bragg ptychography iterative engine, adapted for Bragg diffraction and allowing for the retrieval of the crystal scattering contrast and the illumination function. As usual for the Bragg diffraction case, the scattering contrast is described by a complex-valued function, whose amplitude is associated with the crystal density and whose phase is the projection of the displacement field on the Bragg vector24. As a consequence, the 220 Bragg reflection ptychography reconstruction is expected to image only the features associated to the Si 〈110〉 crystal, that is, the two lines without the substrate. The retrieved sample is shown in Figure 3a–c. In Figure 3a, both lines are retrieved with shape, height and width in agreement with the direct characterizations of Figure 1c,d. The finite extent along the line axis corresponds to the finite illumination of the X-ray beam spot. The internal cross-sections of Figure 3b exhibit a satisfying homogeneous density. However, the density value is different for the two lines. The smaller value observed for the small line is probably resulting from an interplay between the density and the resolution, which is locally degraded: the resolution actually scales with the invert range of the reciprocal space signal, that is less intense for the thinner line. The phase behaviour is shown on cross-sectional views through the lines. For the small line, the phase is homogeneous, as expected for a strain-free crystal. On the contrary, we observe two constant phase domains in the other line, corresponding to a phase shift of about 0.7 rad. The presence of these two phases, observed only in the large crystalline line, finally explains the Bragg peak splitting, evidenced in Figure 2b–d,h. This phase behaviour is the consequence of the coexistence of two crystalline domains, each of them unstrained. These defects have been reported in the literature for crystals produced by Silicon-on-insulator technologies (see ref. 25 and references therein).

The ptychographical iterative algorithm is used to retrieve the crystal scattering contrast, shown here in an orthogonal space. (a) Reconstructed density represented with a 50% iso-surface for each line. The dotted grey lines are a guide to the eye. (b) 2D cross-sectional views of the sample density and (c) phase (in rad.). In (a–c), the black lines represent a 40-nm length; The vertical axis has been stretched out for clarity. The colour scales are given in the figures.

Reconstruction of the illumination wavefield

Finally, the retrieved illumination function is shown in Figure 4. It is taken at the sample position in the plane perpendicular to the beam propagation. The vertical beam size is in good agreement with our estimation of the focus spot size. In the horizontal direction, the retrieved spot is asymmetric and its width matches our expectations from the experimental data analysis, which anticipated an horizontally extended beam spot. These two characteristics, horizontal asymmetry and broadening, are typical effects observed when the central stop partly occludes the rectangular aperture at the FZP21. It results from a non-intentional horizontal offset of the FZP aperture position.

The retrieved illumination function is shown in the plane perpendicular to the X-ray beam propagation. On the right, the colour code used for the colour rendition of the complex-valued function is indicated: the length of the arrow and the angle correspond to the amplitude (linear scale) and phase values, respectively (Scale bar: 200 nm). The amplitude fluctuations are classical artefacts arising from intensity normalization and translational periodicity of tx 14.

Discussion

Bragg ptychography like other Bragg coherent diffraction imaging methods is expected to provide unrevealed views of 3D crystalline materials, including density and displacement field. The most comparable microscopy method is certainly transmission electron microscopy, which makes use of electron diffraction to provide highly spatially resolved images of nanocrystals. However, it requires a thinning down of the sample, which restricts its use to structures with a thickness smaller than about 100 nanometers. In addition, the sample preparation is likely to modify the crystalline internal displacement field. Scanning transmission electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy deliver images with resolution in the nanometer range but are only sensitive to topological aspects. In this context, confronting the 3D images obtained from Bragg coherent diffraction approaches to other well-established techniques is a highly difficult task. The sample we used in our Bragg ptychography approach was originally designed for Bragg Fourier transform holography26. This approach makes use of a reference crystal located nearby the object crystal to image, which thereby directly allows encoding the phase in the intensity pattern. Hence, a single inverse Fourier transform of the 3D intensity hologram allows the retrieval of the object image. The reconstruction image is the convolution of the object crystal exit field with the reference crystal exit field. The retrieved quantity, obtained from the 3D diffraction pattern measured at tx=1.25 μm is shown in Figure 5. The density (Fig. 5a) exhibits height and width in perfect agreement with the dimensions of the crystalline object, while the fine details of the shape are smoothed out by the convolution process. The linear decrease of the density, from a maximum value located in the centre of the object arises from the convolution process as well. The phase (Fig. 5b) shows slow variations with a phase shift in the 1 rad range from the top to the bottom. The good quality of this reconstruction testifies the quality of the measurements. In particular, the presence of a holographic signal confirms the extent of the broadened illumination function over the two Si lines for this probe position. Although this image can not directly be compared with the Bragg ptychography image, the Fourier transform holography results are consistent with the ptychography image. The validity of our 3D Bragg ptychography approach is further testified by the numerical simulation of the whole problem, using detection parameters, sample and illumination functions corresponding to the ones imposed by the experimental conditions. It makes clear that the whole 3D data set obtained from the one-dimensional ptychography scan contains all information needed to retrieve the illumination function and the 3D crystal density and phase.

The retrieved crystal scattering contrast, as obtained from Bragg Fourier transform holography analysis, is shown in an orthogonal space. The retrieved image is the convolution of the large Si line by the small reference line. (a) Reconstructed density represented with a 50% iso-surface and (b) reconstructed phase (in rad.): these images are consistent with the retrieved crystal scattering contrasts of (Fig. 3). The colour scales are given in the figures (Scale bars: 50 nm).

To conclude, we have experimentally demonstrated that Bragg ptychography is able to produce 3D quantitative imaging of an extended crystal. In addition to the shape, we obtained an internal view of the density and displacement field. Owing to the possibility offered by Bragg ptychography to image crystals without transverse size restriction, we believe that this technique will allow for new insight and understanding in a large variety of materials, ranging from the most natural ones like bio-crystals up to the most manufactured systems like microelectronics compounds, both being composed of crystals structured on the nanometer scale.

Methods

Data acquisition

The Bragg ptychography experiment was carried out at the ID01 beamline (European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF)). The monochromatic beam (wavelength λ=0.154 nm) was delivered by a Si-111 monolithic channel-cut monochromator (energy bandwidth of about 1.4×10−4), resulting in a longitudinal coherence length of about 1 μm. To increase the flux at the sample position, a 200-μm diameter Au FZP was placed 129 mm upstream the sample. A 60-μm diameter central stop was placed close to the FZP to avoid direct beam transmission through the FZP central part. The focusing set-up was completed with a 50-μm circular-order-sorting aperture located 10 mm upstream the sample to block the FZP's higher diffraction orders. To ensure a fully coherent beam at the sample position, the focusing optics aperture was set to 80×20 μm2, corresponding to the vertical and horizontal coherence lengths of the beamline, respectively. Necessarily, the aperture was horizontally shifted to one side of the central stop to ensure a large illumination area onto the FZP. The 〈110〉 Si double-line sample was placed in Bragg diffraction geometry (220 reflection, Bragg angle θB=22.35°), with the line axis lying in the scattering plane. The intensity acquisition was performed with a pixel detector (Maxipix, 256×256 pixels of 55×55 μm2 size 27) mounted 1.17 m downstream the sample. The acquisition time was set to 50 s per frame.

The 3D intensity is measured as a function of the reduced momentum transfer vector q=Q−G220, where G220 is the Bragg vector (|G220|=3.3×101 nm−1) and Q=kf−ki (ki (resp. kf) is the incident (resp. diffracted) wavevector with |ki,f|=2π/λ). The q1,2 components lie in the detector plane, vertically and horizontally, respectively (Fig. 1b). The q3 direction, which is probed by scanning the incident angle in steps of 0.04° over an angular range of 0.4°, is perpendicular to G220. These experimental conditions result in a voxel size of 1.9×1.8×22×(10−3)3 nm−3. The full set of ptychography data is obtained by scanning the sample along the direction perpendicular to the scattering plane, using a piezo-electric translation stage. The 13 positions cover a total range of about 4 μm. The whole set-up stability was controlled over hours by a series of X-ray measurements performed before the ptychography scan, showing the absence of beam radiation damage or beam drift in the data set.

Sample preparation

The sample used for this work was produced by e-beam lithography from a continuous Si 〈110〉 layer (180-nm thick) covering a SiO2 film (25-nm thick) onto a Si 〈100〉 substrate (Silicon-on-insulator Smartcut wafer from Soitec). The two-line structure was defined in a positive photo resist (PMMA E-beam resist AR-P631.04) with a thickness of 130 nm, using a SF6 reactive ion etching to transfer the pattern into the Si layer. The etching depth was chosen to remove completely the Si 〈110〉 layer around the two lines, over an area of 100×100 μm2.

Phase retrieval

The whole 3D phase retrieval process is performed in the (q1, q2, q3) reciprocal space frame and the conjugated (r1, r2, r3) direct space frame. At the end, the retrieved quantities are transferred into an orthogonal (x, y, z) space for plotting.

As usual for iterative algorithms, the initialization requires to built a first guess for the sample scattering contrast, ρe (r), and for the illumination volume, Pe (r). Typically, the guessed sample scattering contrast results from the integrated intensity measurement and/or direct characterizations8 whereas a 2D gaussian intensity distribution is used for describing the probe cross-section. The latter is further assumed to be constant along the incident beam propagation. In our work, the constrained PIE (cPIE) is introduced to look for solutions with particular chosen characteristics. The constraint is monitored with a regularization parameter, γ (0≤γ): in particular, when γ=0, the cPIE reduces to the usual PIE. The details of the cPIE, which involves a series of K iterations and N sub-iterations, are summarized in the following:

with 1≤j≤N

For k=1 to K

For j=1 to N

The two first lines describe the initialization in the case where the inversion seeks at refining the sample scattering contrast. Pj is the probe at the Rj position corresponding to the j-th measurement and N is the total number of measurement positions. The core of the algorithm consists in first calculating the exit wave-field ψk,j using the Born approximation (equation (1)). The far-field distribution Ek,j corresponding to the propagation of ψk,j is obtained from a Fourier transform operation (denoted as F, equation (2)). In equation (3), this quantity is corrected so that the estimated intensity matches the experimental data Ij(q). The corrected far-field is then back propagated using inverse Fourier transform operator (F−1, equation (4)). The last step (equation (5)) allows the object estimate to be updated, taking into account the probe function and the overlapping condition. The conjugation operation is denoted by '*'. The β parameter is the step-size for the current correction (0<β) and ɛ avoids division by zero. In addition, a support constraint χ (r) is introduced, leading to the constrained form of the PIE. The expression in equation (5) derives from the minimization of the criterion including the error metric and the penalty term, linked to the constraint 8. These five operations are performed for the N positions of the illumination function, before the updated object is re-introduced in a new iteration. The whole process is repeated K times. By exchanging the role of the probe and the sample scattering functions in the above formulae, the retrieval of the probe function is obtained.

Data inversion

For the presented result, eight cycles were performed, composed of three iterations over the sample followed by two iterations over the illumination. β was set to 0.4 and γ to 0.1. The support constraint allowed the stabilization of the sample position in the computational window. It was introduced as a thin layer box with finite thickness so that the sample height did not extent beyond 50 nm, as determined by atomic force microscopy. The rough shape of the sample estimate is obtained from AFM and SEM observations. A gaussian illumination function was introduced as a first estimate. Its width and height were chosen to provide initially a reasonable agreement with the integrated intensity as measured along tx or along the rocking curve. In addition, to compensate the measurement-sampling rate, too small along the q3 direction, the retrieved volume was increased by a factor of 2 along the r3 direction. It was made possible owing to the smooth variation of the intensity pattern along the rocking curve, where no interference fringe was expected. The 3D phase retrieval was enforced to retrieve not only the experimentally measured (q1, q2) planes but also the missing planes in between. In equation (3), only the measured intensities were imposed. In this way, the computational window was 60 times larger than the illumination function size along r1 and comparable to it along r2 and r3.

The resolution of the reconstruction was evaluated from the sharpness of the density contrast in the vicinity of the line edge. Along the x and z directions, resolutions of about 4 and 2 pixels were found, which correspond to about 90 nm and 40 nm, respectively. This approach could not be used along y because of the geometry of the Si lines. In addition, the low scattered intensity of the small line leads to a higher level of noise, which slightly degrades the resolution in this area. Interestingly, we noted that the inversion with support-based algorithms was not possible when only one single set of 3D intensity data was used, except for the measurements performed at the extreme tx positions. In these cases, only the large line or small line exit field was retrieved.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Godard, P. et al. Three-dimensional high-resolution quantitative microscopy of extended crystals. Nat. Commun. 2:568 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1569 (2011).

References

Newton, M. C., Leake, S. J., Harder, R. & Robinson, I. K. Three-dimensional imaging of strain in a single ZnO nanorod. Nature Mater. 9, 120–124 (2010).

Sayre, D. Some implications of a theorem due to Shannon. Acta. Crystallogr. 5, 843–843 (1952).

Nugent, K. A. Coherent methods in the X-ray sciences. Adv. Phys. 59, 1–99 (2010).

Chamard, V. et al. Strain analysis by inversion of coherent Bragg X-ray diffraction intensity: the illumination problem. J. Mod. Optic. 57, 816–825 (2010).

Minkevich, A. A. et al. Inversion of the diffraction pattern from an inhomogeneously strained crystal using an iterative algorithm. Phys. Rev. B 76, 104106–1–5 (2007).

Diaz, A. et al. Imaging the displacement field within epitaxial nanostructures by coherent diffraction: a feasibility study. New J. Phys. 12, 035006–1–20 (2010).

Vaxelaire, N. et al. 3D strain imaging in sub-micrometer crystals using cross-reciprocal space measurements: Numerical feasibility and experimental methodology. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B 268, 388–393 (2010).

Godard, P., Allain, M. & Chamard, V. Imaging highly non-homogeneous strain fields in nanocrystals using X-ray Bragg ptychography: a numerical study. Phys. Rev. B 84, 144109–1–11 (2011).

Hoppe, W. Beugung im inhomogenen Primaerstrahlwellenfeld. I. Prinzip einer Phasenmessung von Elektronenbeungungsinterferenzen. Acta. Crystallogr. A 25, 495–501 (1969).

Rodenburg, J. M. & Bates, R. The theory of super-resolution electron microscopy via Wignerdistribution deconvolution. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 339, 521–553 (1992).

Bunk, O. et al. Influence of the overlap parameter on the convergence of the ptychographical iterative engine. Ultramicroscopy 108, 481–487 (2008).

Rodenburg, J. M. et al. Hard-X-ray lensless imaging of extended objects. Phys. Rev. Lett 98, 034801–1–4 (2007).

Thibault, P. et al. High-resolution scanning X-ray diffraction microscopy. Science 321, 379–382 (2008).

Dierolf, M. et al. Ptychographic X-ray computed tomography at the nanoscale. Nature 467, 436–439 (2010).

Schropp, A. et al. Non-destructive and quantitative imaging of a nano-structured microchip by ptychographic hard X-ray scanning microscopy. J. Microsc. 241, 9–12 (2010).

Giewekemeyer, K. et al. Quantitative biological imaging by ptychographic X-ray diffraction microscopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 529–534 (2010).

Faulkner, H. M. L. & Rodenburg, J. M. Movable aperture lensless transmission microscopy: A novel phase retrieval algorithm. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 023903–1–4 (2004).

Thibault, P., Dierolf, M., Bunk, O., Menzel, A. & Pfeiffer, F. Probe retrieval in ptychographic coherent diffractive imaging. Ultramicroscopy 109, 338–343 (2009).

Maiden, A. & Rodenburg, J. M. An improved ptychographical phase retrieval algorithm for diffractive imaging. Ultramicroscopy 109, 1256–1262 (2009).

Williams, G. J., Pfeifer, M. A., Vartanyants, I. A. & Robinson, I. K. Three-dimensional imaging of microstructure in Au nanocystals. Phys. Rev. Let. 90, 175501–1–4 (2003).

Mastropietro, F. et al. Coherent X-ray wavefront reconstruction of a partially illuminated Fresnel zone plate. Opt. Express 19, 19223–19232 (2011).

Paganin, D. M. Coherent X-ray Optics (Oxford University Press, 2006).

Schroer, C. G. et al. Coherent X-ray diffraction imaging with nanofocused illumination. Phys. Rev. Lett 101, 090801–1–4 (2008).

Takagi, S. A dynamical theory of diffraction for a distorded crystal. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 26, 1239–1253 (1969).

Shi, X., Xiong, G., Huang, X., Harder, R. & Robinson, I. Structural inhomogeneity in silicon-on-insulator probed with coherent X-ray diffraction. Z. Kristallogr. 225, 610–615 (2010).

Chamard, V. et al. Three-dimensional X-ray Fourier transform holography: The Bragg case. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 165501–1–4 (2010).

Ponchut, C. et al. Photon-counting X-ray imaging at kilohertz frame rates. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 576, 109–112 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to P. Ferrand, A. Sentenac and M. Guizar-Sicairos for fruitful discussions and/or careful reading of the manuscript, and to I. Snigireva for the scanning electron microscopy characterizations of the sample. Further atomic force microscopy images were performed by J.-F. Guillet, who is warmly acknowledged. Finally, we thank the ID01 staff (ESRF) for technical support. This work was funded by the French ANR (ANR-08-JCJC-0095-01), the FWF Vienna (SFB025), the BMWF Vienna, and the PLATON project of the Austrian Nanoinitiative.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C. provided the sample wafer. J.S. and G.C. fabricated the test pattern and performed the AFM measurements. D.C., A.D, L.C., T.H.M. and V.C. carried out the experiment. F.M. characterized the beam. P.G. and M.A. wrote the algorithm and P.G. analysed the data. V.C. conceived the experiment and wrote the paper with contributions from all.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Godard, P., Carbone, G., Allain, M. et al. Three-dimensional high-resolution quantitative microscopy of extended crystals. Nat Commun 2, 568 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1569

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1569

This article is cited by

-

4th generation synchrotron source boosts crystalline imaging at the nanoscale

Light: Science & Applications (2022)

-

High resolution strain mapping of a single axially heterostructured nanowire using scanning X-ray diffraction

Nano Research (2020)

-

Three-dimensional X-ray diffraction imaging of dislocations in polycrystalline metals under tensile loading

Nature Communications (2018)

-

X-ray ptychography

Nature Photonics (2018)

-

High-resolution three-dimensional structural microscopy by single-angle Bragg ptychography

Nature Materials (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.