Abstract

The enantioselective silylation of racemic alcohols, where one enantiomer reacts faster than the other, is an alternative approach to established enzymatic and non-enzymatic acylation techniques. The existing art is either limited to structurally biased alcohols or requires elaborate catalysts. Simple substrates, such as benzylic and allylic alcohols, with no coordinating functionality in the proximity of the hydroxy group have been challenging in these kinetic resolutions. We report here the identification of a broadly applicable chiral catalyst for the enantioselective dehydrogenative coupling of alcohols and hydrosilanes with both the chiral ligand and the hydrosilane being commercially available. The efficiency of kinetic resolutions is characterized by the selectivity factor, that is, the ratio of the reaction rates of the fast-reacting over the slow-reacting enantiomer. The selectivity factors achieved with the new method are good for acyclic benzylic alcohols (≤170) and high for synthetically usefully cyclic benzylic (≤40.1) and allylic alcohols (≤159).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

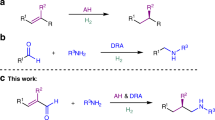

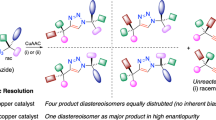

A common method to kinetically resolve alcohols is by acylation, either enzymatic or non-enzymatic1. Conversely, non-enzymatic kinetic resolution through catalytic alcohol silylation had been unknown until a decade ago (Fig. 1a)2,3,4. Part of the attractiveness of this transformation lies in rendering an often-used alcohol protection enantioselective. The ‘obvious’ strategy of achieving this goal is by the design of chiral imidazole-based catalysts for chlorosilane activation, that is, an asymmetric version of the original Corey–Venkateswarlu protocol5. It was Hoveyda and Snapper6,7,8,9,10 and, later, Tan11,12,13,14,15 to introduce such catalysts that enable the kinetic resolution7,9,12,15 and, likewise, desymmetrization6,8,10,11,13,14 of 1,2-diol motifs but not monools (Strategy 1). Inspired by an early contribution by Ishikawa16, Wiskur used isourea-based catalysts to kinetically resolve cyclic monools with decent success (Strategy 1 and Fig. 1b)17,18,19,20,21. Just recently, Song22 presented a broadly applicable solution to the long-standing challenge of resolving simple alcohols, typically 1-phenylethan-1-ol derivatives, by Brønsted-acid catalysis (Strategy 2 and Fig. 1b). Desymmetrization of selected 1,2-diols was also demonstrated22,23.

Our laboratory had approached the problem from a different angle. We had used Cu–H catalysis to couple alcohols and hydrosilanes with release of dihydrogen (Strategy 3 and Fig. 2a)24,25. The resulting silyl ether is usually considered waste in the catalytic generation of copper(I) hydride-reducing agents. At that time, we had chosen the dehydrogenative Si–O coupling because it allowed us to employ silicon-stereogenic hydrosilanes as resolving reagents (Fig. 2b). Unlike chlorosilanes, these react without racemization with hydroxy groups. By this, we accomplished the reagent-controlled kinetic resolution of alcohols with an achiral monodentate phosphine ligand at the copper(I) atom26,27,28,29,30. We were later able to turn this kinetic resolution into a catalyst-controlled process with a chiral monodentate ligand and achiral hydrosilanes31. However, both transformations required alcohols with pending donors (TS1 and TS2, Fig. 2c), making two-point binding of the substrate the salient feature of these coupling reactions. All subsequent attempts to extend this methodology to monools had failed for years32,33 until we discovered that a chiral bidentate ligand together with trialkylsilanes having long aliphatic chains lead to high selectivity factors (TS3, Fig. 2c). We disclose here the Cu–H-catalysed enantioselective silylation of structurally non-biased alcohols, including synthetically useful allylic alcohols, with both a commercially available catalyst and hydrosilane.

Results

Catalyst identification and optimization

An extensive screening of chiral ligands finally culminated in the identification of commercial (R,R)-Ph-BPE [L1, 1,2-bis((2R,5R)-2,5-diphenylphospholano)ethane] as a superior ligand in the catalytic asymmetric Si–O coupling of 1-phenylethan-1-ol and structurally related congeners (see Supplementary Table 1 for the complete ligand survey)32,34,35,36,37. Systematic variation of the copper(I) source, base and solvent did not reveal any evidence of a trend, and these data are collected in Supplementary Tables 2–4. The CuCl–NaOtBu system in toluene was subsequently used in the further optimization of the model reaction 1a→3a/1a (Table 1). The selectivity factor was low with Ph3SiH (2a, s=2.96, entry 1) but at least moderate with MePh2SiH and Me2PhSiH (2b, s=5.52, entry 2 and 2c, s=6.33, entry 3). However, any steric and electronic modification of the aryl groups in these diarylmethyl- and aryldimethylsilanes had little effect (s≈5 and s≈6, respectively), if at all resulting in less reactive hydrosilanes (see Supplementary Table 5 for the collection of tested hydrosilanes). We then found that linear alkyl substituents instead of the methyl group(s) dramatically improved the selectivity factor, reaching promising s values of 10.0 with 2d (entry 4) and 10.6 with 2e (entry 5). This prompted us to (re-)investigate trialkylsilanes as coupling partners. We had initially excluded these from the present study because of their lack of reactivity in our earlier catalyst-controlled kinetic resolution of donor-functionalized alcohols31. To our delight, trialkylsilanes 2f–2i consistently yielded selectivity factors above 10 (entries 6–9), and the best value was obtained for 2h with n-butyl groups (s=14.3, entry 8). Branching close to the silicon atom as in 2j–2l was detrimental (entries 10–12), and tert-butyl substituents were generally not accepted (not shown). Bn3SiH performed also well (2m, s=11.6, entry 13) but was inferior to nBu3SiH (2h, cf. entry 8). Reactions were routinely run for 18 h to achieve synthetically useful conversions. To boost the reactivity28, we tested cyclic and, hence, more Lewis-acidic hydrosilane 2n but the enormous reactivity gain was at the expense of selectivity (s=3.51, entry 14). Also, alkoxy-substituted hydrosilanes, such as (EtO)3SiH (2o), reacted rapidly yet without any asymmetric induction (entry 15). Cognate ligands (S,S)-Me-BPE (L2) and (R,R)-iPr-BPE (L3) with different R groups either led to a catalytically inactive copper(I) complex (entry 16) or a clearly lower s value (entry 17) with nBu3SiH (2h) (cf. entry 8).

Scope and limitations

We continued by exploring the substrate scope with this readily accessible catalytic set-up (CuCl/L1–NaOtBu and nBu3SiH, Figs 3 and 4). An analysis of the steric effects in 1-phenylethan-1-ol derivatives showed that monosubstitution of the aryl group in any of the three available positions with methyl groups is not significantly influencing the reaction outcome; selectivity factors for 1b–e were in the same range, just slightly better in the case of the ortho-substituted substrate (Fig. 3b). Additional methyl substitution as in 1f and 1g generally had little effect but selectivity factors increased substantially with CF3 (as in 1h) or OMe (as in 1i) instead of the methyl groups. The substituent effect was dramatic for substrates with both ortho positions occupied; selectivity factors for 1j and 1k were exceedingly high (Fig. 3b). When increasing the size of the alkyl group at the carbinol carbon atom, Me (1a/1b)<Et (1l)<Bn (1m)<iPr (1n), the selectivity factor collapses (12.2/14.6>11.6>9.93>>3.00) while maintaining sufficient reactivity; this effect is also seen for mesityl-substituted 1o but 81.4 is still an excellent s value (highlighted by grey ovals, Fig. 3b). Both β- and α-naphthyl-substituted derivatives 1p and 1q fit into the observed selectivity pattern (Fig. 3b). The selectivity factors for the acyclic benzylic alcohols 1a–q were uniformly lower than those obtained with Song’s Brønsted-acid catalyst (Strategy 2, Fig. 1)22. Conversely, cyclic substrates 1r–w not reported by Song22 afforded synthetically valuable selectivity factors independent of the ring size, 1r–t, and with excellent functional-group tolerance, 1u–w (Fig. 3c). Our results compare favourably with those described by Wiskur for the same class of compounds using chlorosilanes (Strategy 1, Fig. 1)17.

We also investigated the resolution of isomerically pure 2-phenylcyclohexan-1-ols trans-4 and cis-4 with reasonable success (Fig. 3d). Various types of these compounds had been subject of a dedicated study by Wiskur (Strategy 1, Fig. 1)21, and Wiskur found that, from an isomeric mixture of 4, the isourea-based catalyst preferentially selects the trans over the cis relative configuration in the kinetic resolution of 4. Our catalytic system showed the same preference in the individual experiments. Both kinetic resolutions were slow, reaching useful conversion after several days only for trans-4. The selectivity factor was markedly higher than that achieved by Wiskur21 (s=29.1 versus s=10).

While both acyclic22 and cyclic17 benzylic alcohols had been resolved by other catalytic methods before, just one example of an acyclic allylic alcohol, (E)-1,3-diphenylprop-2-en-1-ol, was described22. Allylic alcohols are however ubiquitous synthetic building blocks and, as such, particularly attractive substrates. Without making any changes to our catalytic set-up, allylic alcohols were equally amenable to this enantioselective alcohol silylation but underwent competing partial alkene reduction38. This issue was overcome by the substoichiometric addition of a sacrificial, more reactive alkene, styrene39,40 (Fig. 4a). With this measure, representative allylic alcohols 6a–d were resolved with excellent selectivity factors (Fig. 4b). Cyclic systems with exo- and endocyclic double bonds, 6e and 6f as well as 8, participated in this kinetic resolution with superb efficiency (s>55, Fig. 4c). The functional-group tolerance was expanded further by a vinylic bromide (as in 6c). For comparison, we subjected purely aliphatic alcohol 10 to the standard protocol, and the selectivity factor (s=9.62, Fig. 4d) was lower than those obtained for allylic alcohol 6d (s=14.4, Fig. 4b) and benzylic alcohol 1b (s=14.6, Fig. 3b). This indicates that the π system attached to the carbinol carbon atom is important for enantiomer discrimination by the catalyst.

Discussion

We have disclosed here that the commercially available CuCl/(R,R)-Ph-BPE–NaOtBu catalyst system allows for the kinetic resolution of alcohols by enantioselective Si–O coupling. The choice of the hydrosilane coupling partner is crucial as high selectivity factors have only been achieved with trialkylsilanes, and commercial nBu3SiH was used throughout this study. This easy-to-apply catalyst–hydrosilane combination kinetically resolves a broad range of structurally unbiased benzylic and allylic alcohols, reaching synthetically useful selectivity factors for cyclic benzylic (s≤40.1, Fig. 3c) and various allylic alcohols (s≤159, Fig. 4b,c). It must be emphasized here that the inaccuracy of the analytical tools to measure conversion and enantiomeric purity leads to imprecise selectivity factors, particularly for s>50 (refs 27, 41). Hence, the reported values are not exact but rather an approximation of the order of magnitude. While the present protocol is limited to secondary alcohols, we will now tackle the most difficult class of alcohols in this chemistry, tertiary alcohols28.

Methods

General

Supplementary Figs 1–122 for the HPLC traces, Supplementary Figs 123–256 for the NMR spectra and Supplementary Methods with full experimental details, and the characterization of compounds are given in the Supplementary Information.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information file.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Dong, X. et al. Broad-spectrum kinetic resolution of alcohols enabled by Cu–H-catalysed dehydrogenative coupling with hydrosilanes. Nat. Commun. 8, 15547 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15547 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Vedejs, E. & Jure, M. Efficiency in nonenzymatic kinetic resolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 3974–4001 (2005).

Rendler, S. & Oestreich, M. Kinetic resolution and desymmetrization by stereoselective silylation of alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 248–250 (2008).

Weickgenannt, A., Mewald, M. & Oestreich, M. Asymmetric Si–O coupling of alcohols. Org. Biomol. Chem. 8, 1497–1504 (2010).

Xu, L.-W., Chen, Y. & Lu, Y. Catalytic silylations of alcohols: turning simple protecting-group strategies into powerful enantioselective synthetic methods. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 9456–9466 (2015).

Corey, E. J. & Venkateswarlu, A. Protection of hydroxyl groups as tert-butyldimethylsilyl derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 94, 6190–6191 (1972).

Zhao, Y., Rodrigo, J., Hoveyda, A. H. & Snapper, M. L. Enantioselective silyl protection of alcohols catalysed by an amino-acid-based small molecule. Nature 447, 67–70 (2006).

Zhao, Y., Mitra, A. W., Hoveyda, A. H. & Snapper, M. L. Kinetic resolution of 1,2-diols through highly site- and enantioselective catalytic silylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 8471–8474 (2007).

You, Z., Hoveyda, A. H. & Snapper, M. L. Catalytic enantioselective silylation of acyclic and cyclic triols: application to total syntheses of cleroindicins D, F, and C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 547–550 (2009).

Rodrigo, J. M., Zhao, Y., Hoveyda, A. H. & Snapper, M. L. Regiodivergent reactions through catalytic enantioselective silylation of chiral diols. Synthesis of sapinofuranone A. Org. Lett. 13, 3778–3781 (2011).

Manville, N., Alite, H., Haeffner, F., Hoveyda, A. H. & Snapper, M. L. Enantioselective silyl protection of alcohols promoted by a combination of chiral and achiral Lewis basic catalysts. Nat. Chem. 5, 768–774 (2013).

Sun, X., Worthy, A. D. & Tan, K. L. Scaffolding catalysts: highly enantioselective desymmetrization reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 8167–8171 (2011).

Worthy, A. D., Sun, X. & Tan, K. L. Site-selective catalysis: toward a regiodivergent resolution of 1,2-diols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7321–7324 (2012).

Tan, K. L., Sun, X. & Worthy, A. D. Scaffolding catalysis: expanding the repertoire of bifunctional catalysts. Synlett 23, 321–325 (2012).

Giustra, Z. X. & Tan, K. L. The efficient desymmetrization of glycerol using scaffolding catalysis. Chem. Commun. 49, 4370–4372 (2013).

Sun, X., Worthy, A. D. & Tan, K. L. Resolution of terminal 1,2-diols via silyl transfer. J. Org. Chem. 78, 10494–10499 (2013).

Isobe, T., Fukuda, K., Araki, Y. & Ishikawa, T. Modified guanidines as chiral superbases: the first example of asymmetric silylation of secondary alcohols. Chem. Commun. 2001, 243–244 (2001).

Sheppard, C. I., Taylor, J. L. & Wiskur, S. L. Silylation-based kinetic resolution of monofunctional secondary alcohols. Org. Lett. 13, 3794–3797 (2011).

Clark, R. W., Deaton, T. W., Zhang, Y., Moore, M. I. & Wiskur, S. L. Silylation-based kinetic resolution of α-hydroxy lactones and lactams. Org. Lett. 15, 6132–6135 (2013).

Akhani, R. K., Moore, M. I., Pribyl, J. G. & Wiskur, S. L. Linear free-energy relationship and rate study on a silylation-based kinetic resolution: mechanistic insights. J. Org. Chem. 79, 2384–2396 (2014).

Akhani, R. K. et al. Polystyrene-supported triphenylsilyl chloride for the silylation-based kinetic resolution of secondary alcohols. ChemCatChem. 7, 1527–1530 (2015).

Wang, L., Akhani, R. K. & Wiskur, S. L. Diastereoselective and enantioselective silylation of 2-arylcyclohexanols. Org. Lett. 17, 2408–2411 (2015).

Park, S. Y., Lee, J.-W. & Song, C. E. Parts-per-million level loading organocatalysed enantioselective silylation of alcohols. Nat. Commun. 6, 7512 (2015).

Hyodo, K., Gandhi, S., van Gemmeren, M. & List, B. Brønsted acid catalyzed asymmetric silylation of alcohols. Synlett. 26, 1093–1095 (2015).

Rendler, S. & Oestreich, M. Polishing a diamond in the rough: ‘Cu–H’ catalysis with silanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 498–504 (2007).

Deutsch, C., Krause, N. & Lipshutz, B. H. CuH-catalyzed reactions. Chem. Rev. 108, 2916–2927 (2008).

Rendler, S., Auer, G. & Oestreich, M. Kinetic resolution of chiral secondary alcohols by dehydrogenative coupling with recyclable silicon-stereogenic silanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 7620–7624 (2005).

Klare, H. F. T. & Oestreich, M. Chiral recognition with silicon-stereogenic silanes: remarkable selectivity factors in the kinetic resolution of donor-functionalized alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 9935–9938 (2007).

Karatas, B., Rendler, S., Fröhlich, R. & Oestreich, M. Kinetic resolution of donor-functionalised tertiary alcohols by Cu–H-catalysed stereoselective silylation using a strained silicon-stereogenic silane. Org. Biomol. Chem. 6, 1435–1440 (2008).

Rendler, S. et al. Stereoselective alcohol silylation by dehydrogenative Si–O coupling: scope, limitations, and mechanism of the Cu–H-catalyzed non-enzymatic kinetic resolution with silicon-stereogenic silanes. Chem. Eur. J. 14, 11512–11528 (2008).

Steves, A. & Oestreich, M. Facile preparation of CF3-substituted carbinols with an azine donor and subsequent kinetic resolution through stereoselective Si–O coupling. Org. Biomol. Chem. 7, 4464–4469 (2009).

Weickgenannt, A., Mewald, M., Muesmann, T. W. T. & Oestreich, M. Catalytic asymmetric Si–O coupling of simple achiral silanes and chiral donor-functionalized alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 2223–2226 (2010).

Weickgenannt, A. Katalytische Enantioselektive Silylierung von Alkoholen (PhD dissertation, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, 2010).

Issenhuth, J. T., Dagorne, S. & Bellemin-Laponnaz, S. A practical concept for the kinetic resolution of a chiral secondary alcohol based on a polymeric silane. J. Mol. Cat. A 286, 6–10 (2008).

Ascic, E. & Buchwald, S. L. Highly diastereo- and enantioselective CuH-catalyzed synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted indolines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4666–4669 (2015).

Wang, Y.-M. & Buchwald, S. L. Enantioselective CuH-catalyzed hydroallylation of vinylarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 5024–5027 (2016).

Bandar, J. S., Ascic, E. & Buchwald, S. L. Enantioselective CuH-catalyzed reductive coupling of aryl alkenes and activated carboxylic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 5821–5824 (2016).

Yang, Y., Perry, I. B., Lu, G., Liu, P. & Buchwald, S. L. Copper-catalyzed asymmetric addition of olefin-derived nucleophiles to ketones. Science 353, 144–150 (2016).

Shi, S.-L., Wong, Z. L. & Buchwald, S. L. Copper-catalysed enantioselective stereodivergent synthesis of amino alcohols. Nature 532, 353–356 (2016).

Miki, Y., Hirano, K., Satoh, T. & Miura, M. Copper-catalyzed intermolecular regioselective hydroamination of styrenes with polymethylhydrosiloxane and hydroxylamines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 10830–10834 (2013).

Zhu, S., Niljianskul, N. & Buchwald, S. L. Enantio- and regioselective CuH-catalyzed hydroamination of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 15746–15749 (2013).

Goodman, J. M., Köhler, A.-K. & Alderton, S. C. M. Interactive analysis of selectivity in kinetic resolutions. Tetrahedron Lett. 40, 8715–8718 (1999).

Kagan, H. B. & Fiaud, J. C. in Topics in Stereochemistry Vol. 18 (eds Eliel, E. L. & Wilen, S. H.) 249–330 (Wiley, 1988).

Acknowledgements

X.D. thanks the China Scholarship Council for a predoctoral fellowship (2014–2018). A.W. was in part supported by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie through a predoctoral fellowship (2008–2010). M.O. is indebted to the Einstein Foundation (Berlin) for an endowed professorship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.D. and M.O. conceived and designed the experiments and discussed the results. X.D. performed the experiments and analysed the data, and A.W. contributed to the ligand identification. M.O. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary figures, supplementary tables, supplementary methods and supplementary references. (PDF 9583 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, X., Weickgenannt, A. & Oestreich, M. Broad-spectrum kinetic resolution of alcohols enabled by Cu–H-catalysed dehydrogenative coupling with hydrosilanes. Nat Commun 8, 15547 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15547

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15547

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.