Abstract

Materials with a negative Poisson’s ratio, also known as auxetic materials, exhibit unusual and counterintuitive mechanical behaviour—becoming fatter in cross-section when stretched. Such behaviour is mostly attributed to some special re-entrant or hinged geometric structures regardless of the chemical composition and electronic structure of a material. Here, using first-principles calculations, we report a class of auxetic single-layer two-dimensional materials, namely, the 1T-type monolayer crystals of groups 6–7 transition-metal dichalcogenides, MX2 (M=Mo, W, Tc, Re; X=S, Se, Te). These materials have a crystal structure distinct from all other known auxetic materials. They exhibit an intrinsic in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio, which is dominated by electronic effects. We attribute the occurrence of such auxetic behaviour to the strong coupling between the chalcogen p orbitals and the intermetal t2g-bonding orbitals within the basic triangular pyramid structure unit. The unusual auxetic behaviour in combination with other remarkable properties of monolayer two-dimensional materials could lead to novel multi-functionalities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Poisson’s ratio of a material characterizes its response to uniaxial load and is given by νab=−ɛb/ɛa, where ɛa is an applied strain in the a axis direction and ɛb is the resulting strain in a transverse b axis direction. Counter-intuitively, negative Poisson’s ratio (auxetic) materials1 expand laterally when stretched and contract laterally when compressed. They can lead to enhanced mechanical properties, such as shear modulus2, indentation resistance3 and fracture toughness4. The unusual auxetic effect itself and concomitant enhancements in other material properties offers enormous potential in many technologically important applications5,6,7, such as biomedicine8, sensors9, fasteners10 and protective equipments11.

Auxetic effect has been reported in a number of natural and man-made materials and structures in bulk form5,6,12,13, for example, cubic metals14,15, α-cristobalite (SiO2)16, α-TeO2 (ref. 17), the zeolite mineral natrolite18, honeycombs19, foams7, microporous polymers20,21, composites22,23, ceramics24, molecular auxtics25, metal-organic frameworks26, bucklicrystals27 and origami structures28,29,30. Geometric considerations dominate the literature in understanding such auxetic effects and designing new auxetic materials. For most of these auxetic materials, the auxetic effect is explained by some special re-entrant structure or the crystal structure that can be viewed as being made up of rigid building blocks linked by flexible hinges1,19,31,32,33, independent of their chemical composition and electronic structure.

Auxetic effect has also been recently reported in several monolayer two-dimensional (2D) materials. For example, the out-of-plane negative Poisson’s ratio was discovered in phosphorene34,35, GeS36 and monolayer arsenic37. The in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio was also predicted in borophene38 and three theoretically proposed but not-yet-synthesized materials (that is, the penta-graphene39,40, hα-silica41 and Be5C2 (ref. 42)). Similar to that in the bulk auxetic materials, the auxetic behaviour in these 2D materials is also considered to originate mainly from the puckered or buckled crystal structure.

In this study, using quantum mechanical first-principles calculations (see Methods section), we report a class of auxetic single-layer 2D materials with an intrinsic in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio. They differ from other known auxetic materials not only in their crystal structure but also in the microscopic origin of auxetic behaviour. These materials are the 1T-type crystalline monolayers of groups 6–7 transition metal dichalcogenides, 1T-MX2 (M=Mo, W, Tc, Re; X=S, Se, Te). In contrast to those known bulk or 2D auxetic materials, the in-plane auxetic behaviour discovered in groups 6–7 1T-MX2 cannot be explained merely from their geometric structure because the non-auxetic behaviour is also found in other groups of MX2 compounds with the same 1T-type structure. This dichotomy between auxetic and non-auxetic behaviour in the 1T-MX2 compounds is explained by their distinct electron structures. The in-plane stiffness of those 1T-MX2 materials is predicted to be order of 102 GPa, at least three orders of magnitude higher than man-made auxetic materials. The high in-plane stiffness and the auxetic behaviour in combination with other remarkable electronic and optoelectronic properties of the single-layer 2D materials43 could lead to novel multi-functionalities, such as nanoscale auxetic electrodes and sensors.

Results

Crystal structure

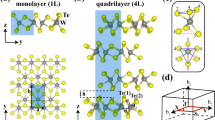

The single layers of 2D transition metal dichalcogenides are formed by a hexagonally packed layer of metal (M) atoms sandwiched between two layers of chalcogen (X) atoms (Fig. 1). Each chalcogen atom forms the apex of a triangular pyramid that has three metal atoms at its base. The symmetry of the chalcogen array about each metal atom is either octahedral or trigonal prismatic. The former is often referred to as the 1T phase, whereas the latter as the 1H phase. Depending on the combination of the metal and chalcogen elements, one of the two phases is thermodynamically preferred. Most group-6 MX2 compounds thermodynamically prefer the 1H phase44, but the metastable 1T phase is also observed45,46,47. For other groups of layered MX2 compounds, most crystallize in the high-symmetry 1T or low-symmetry distorted 1T phase44,48. The 1H-MX2 compounds are known to be non-auxetic in the plane due to their hexagonal in-plane crystalline structure. We hence focus on 42 monolayer MX2 compounds in the high-symmetry 1T phase (Table 1).

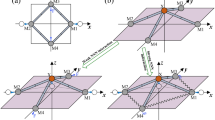

(a) Crystal structure. The basic X-M1-M2-M3 triangular pyramid unit is marked. The rectangular outline displays the unit cell adopted in our calculation. It contains two MX2 formula units. (b) Local structure of M-centred octahedron. The metal atoms form three one-dimensional chains in the directions of y=x, z=y and z=−x in the local reference frame. The M–M interaction is through the t2g-orbital coupling. (c) Schematic configuration of DOS showing the gradual filling of d orbitals from group 4 (d0) to group 10 (d6) 1T-MX2. The horizontal bars denote the corresponding Femi level of the system. t2g and t2g* correspond to the intermetal t2g-bonding and t2g-antibonding states, respectively. (d) Predicted M–X–M bond angles in the relaxed structure of strain-free 1T MX2. Note, in the triangular pyramid as shown in Fig. 1a, ∠M1XM2=∠M2XM3=∠M3XM1=∠MXM.

Poisson’s ratio results

Figure 2a shows our calculated Poisson’s ratio results (νab) for 42 1T-MX2 compounds in the b axis direction subjected to a 5% tensile strain applied along the a axis direction. Remarkably, we find that the sign of Poisson’s ratio strongly depends on the d-electron count. All 12 1T-MX2 compounds from group 6 (d2) and group 7 (d3) exhibit negative Poisson’s ratios, ranging from −0.03 to −0.37. Seven of them (that is, TcTe2, ReTe2, WTe2, WSe2, MoSe2, ReS2 and TcS2) have a Poisson’s ratio <−0.1, higher in magnitude than that of borophene (−0.04 along a and −0.02 along b)38, rendering them more promising candidates for specific applications in mechanical nanodevices. For other groups of 1T-MX2 compounds, we find positive Poisson’s ratios ranging from 0.09 to 0.53.

Figure 2b,c shows our calculated Poisson’s ratios (νab and νba) as a function of applied strain in two example compounds, non-auxetic ZrS2 and auxetic MoS2. For both compounds, Poisson’s ratio varies slowly as applied strain goes from −5% to 5%, suggesting a dominant linear elastic behaviour within the strain range considered. (Note the Poisson’s ratio at a large strain (that is, >5% or <−5%) may strongly depend on the strain. This behaviour is not pursued in this work since such large strains are often experimentally inaccessible.) The small differences between νab and νba reflect a nearly isotropic auxetic or non-auxetic behaviour inside the 1T-structure plane. Therefore, the d-electron count dependence of the sign of Poisson’s ratio as shown in Fig. 2a does not change with respect to the amount of the applied strain within the linear elastic range and the loading direction inside the plane.

Stiffness

To compare the stiffness (Young’s modulus) of a single-layer material with bulk materials, we calculate its 3D in-plane stiffness (Y3D) from 2D in-plane stiffness (Y2D) and effective layer thickness (t) via Y3D=Y2D/t. The Y2D is directly derived from first-principles total energies as a function of uniaxial strain. The effective layer thickness t can also be uniquely determined from first-principles calculated bending energy49. Here for simplicity, we approximate t as t=t0+0.8 Å, where t0 is the distance between the top and bottom chalcogen atom layers and the 0.8 Å is the total effective decay length (0.4 Å in each layer side) of electron density into the vacuum. The 0.8 Å is derived from the first-principles calculated layer thickness for 1H-MoS2 (ref. 49). MSe2 and MTe2 may have different decay lengths than MS2. However, such difference should be less than one time of magnitude. Hence, using a different decay length does not induce one time of magnitude difference in the calculated 3D in-plane stiffness.

Table 1 shows that the 3D in-plane stiffness of almost all 1T-MX2 compounds lies in between 100 and 300 GPa. Among the auxetic d2–d3 1T-MX2 compounds, WS2 and ReSe2 are the stiffest, having a stiffness of ∼290 GPa; TcTe2 is the softest, having a stiffness of ∼80 GPa. Man-made auxetic materials typically have a stiffness in the range from ∼10−5 to ∼1 GPa, and naturally occurring auxetic bulk solids exhibit a stiffness of ∼101–102 Pa (ref. 50). Therefore, even considering the uncertainty of our calculated 3D stiffness (less than one order of magnitude) that may be caused by using different approximations for effective layer thickness, the 3D stiffness values predicted for 1T-MX2 compounds are among the highest in the naturally occurring crystalline solids and are at least three orders of magnitude higher than man-made auxetic materials.

The fact that both auxetic and non-auxetic materials are found in the same 1T-structure type implies that the auxetic effect is not a purely geometric property. The d-electron count dependence of electronic structure must be involved. In the 1T structure, the d orbitals of the octahedrally coordinated transition metal split into two groups, dxy,yz,zx (t2g) and  (eg). In what follows, we shall show that (i) transition metals interact with each other through t2g-orbital coupling, and (ii) the coupled t2g orbitals are further coupled with the lone-pair electrons of chalcogen atoms. It is the gradual filling of such t2g-p-hybridized bands that leads to the different behaviour of Poisson’s ratio.

(eg). In what follows, we shall show that (i) transition metals interact with each other through t2g-orbital coupling, and (ii) the coupled t2g orbitals are further coupled with the lone-pair electrons of chalcogen atoms. It is the gradual filling of such t2g-p-hybridized bands that leads to the different behaviour of Poisson’s ratio.

Intermetal t2g-orbital coupling

In the ideal 1T phase, the M-centred octahedra share edges, forming three one-dimensional M-chains along the directions of lines y=x, y=z, and z=−x, respectively, within the local reference frame of the octahedra (Fig. 1b). The metal atoms can interact with each other through the coupling between their t2g orbitals. This coupling gives rise to t2g-bonding states and t2g-antibonding states, with no energy gap in between due to the weak coupling nature. The t2g states are mostly located within the gap between the bonding and antibonding bands of the M–X bonds (Fig. 1c).

The progressive filling of these t2g bands from group 4 (d0) to group 10 (d6) species leads to different M–M bonding or antibonding character at the Fermi level. In d1-d3 1T-MX2, the Fermi level crosses the t2g-bonding states; the highest occupied bands close to the Fermi-level thus exhibit a stronger bonding character as we go from d1 to d3. This bonding character attracts the metal atoms towards each other, leading to an intermetal distance shorter than that in the ideal 1T structure. In d5–d6 1T-MX2, since the t2g bonding states can accommodate up to six electrons (three from each metal), all t2g-bonding states are filled and the Fermi level crosses the t2g-antibonding states. Hence the highest occupied bands in the vicinity of the Fermi level exhibit antibonding character, repelling metal atoms from each other.

The existence of the intermetal t2g-orbital interactions is reflected by the d-electron count dependence of the M–X–M bond angles (∠MXM) as illustrated in Fig. 1d. The ideal 1T phase has regular octahedra with ∠MXM=90°. In the d0 1T-MX2 compounds, the ∠MXM deviates least from 90°. This is expected since all t2g states are almost completely unoccupied and the intermetal d–d interaction is marginal. For the d1–d3 1T-MX2, all have acute ∠MXM, decreasing with the increasing d-electron count. This trend arises from the increasing intermetal t2g-bonding character in going from d1 to d3, which shortens the intermetal distance. In the d5–d6 1T-MX2, the ∠MXM jumps up to over 90°, consistent with the intermetal t2g-antibonding character.

Figure 1d also shows that the chalcogen atoms have minor effect on ∠MXM compared with the transition metals with different d-electron counts, but a trend can still be observed: the ∠MXM decreases with increasing atomic number of the chalcogen. For example, the ∠MXM of TiS2, TiSe2 and TiTe2 decreases from 89.6° to 88.2° to 86.0°. This trend is not associated with the intermetal t2g-orbital interaction; instead it is intrinsic to the spatial distribution of the lone-pair charge density relative to that of the M–X bonds around the chalcogen.

t2g–p-orbital coupling

The intermetal t2g orbitals are further coupled with chalcogen p orbitals in 1T-MX2. It can be seen from their projected density of states (DOS) as shown in Fig. 3. In the 4d transition metal disulfides with the ideal 1T structure, we find that the DOS of sulfur 3p and metal t2g states overlap, as manifested by their similar DOS peak shapes and positions in energy. The t2g–p-orbital overlap is marginal in d0 ZrS2, but it increases quickly in going from d1 NbS2 to d6 PdS2. This trend is clear not only in the energy range from −12 to −7 eV, where the major peaks of 3p DOS are located, but also near the Fermi level.

The t2g-p orbital coupling manifests itself in the overlap of their DOS. The local reference frame in the octahedral is used for projecting DOS. The DOS shown in the figure are t2g=dxy+dyz+dzx, eg= +

+ and p=px+py+pz. The vertical dashed lines show the position of Fermi level. The energy is aligned to the vacuum level.

and p=px+py+pz. The vertical dashed lines show the position of Fermi level. The energy is aligned to the vacuum level.

The t2g–p-orbital interaction is attractive because the X ligand has one lone electron pair and acts as a sigma donor. In d1–d3 MX2, the t2g–p coupling force draws atom X towards the intermetal bond centres, because the t2g states are the intermetal bonding states spreading over the M–M bond centers. In d5–d6 MX2, the t2g–p coupling force attracts atoms M and X towards each other, because the t2g states are antibonding and localized near the metal atoms. The d-electron count dependence of t2g–p interaction direction plays a key role in determining the structure deformation presented below.

Deformation mechanism

To understand the microscopic origin of Poisson’s ratios, let us now look into the resulting structural relaxation subjected to a tensile strain applied along the a axis. Due to the centrosymmetric nature of the 1T phase, the whole relaxation process manifests itself in the triangular pyramid unit as illustrated in Fig. 4. For the stretch along the M1–M3 axis (that is, axis a), the resulting relaxation involves only atoms M2 and X moving inside the Q–X–M2 plane. Hence, two relations always hold during relaxation: and ∠M1XM2=∠M3XM2.

The solid and dashed M–X bonds indicate, respectively, the initial and final configurations at each relaxation step. The force is applied along the lattice-a direction. The red dashed arrows indicate the direction of the t2g-p orbital interaction. The hollow blue arrows show the resulting movement of the X and M2 atoms within the Q–X–M2 plane.

We analyse the relaxation process by decomposing it into three consecutive steps: (i) atom X relaxes along the line Q–X, (ii) atom X rotates around the M1–M3 axis, and (iii) atom M2 relaxes along the line Q–M2. In the first two steps, the lattice constant b is fixed to the value found in the relaxed strain-free 1T structure. In the third step, b varies as atom M2 moves along the Q–M2 line, leading to different Poisson’s ratio behaviour.

Figure 4 shows the detailed structural relaxation in the three consecutive steps described above for 1T-MX2 with ∠QXM2<90° (Fig. 4a) and with ∠QXM2>90° (Fig. 4b) separately. Each step can be understood in the way that atom X (or atoms X and M2) relaxes to conserve the M–X bond length (dMX) since dMX is energetically dominant. After the first two steps of the relaxation, it can be seen that (i) both (also ) and ∠M1XM2 and ∠M3XM2 (Supplementary Fig. 1) increase in all 1T-MX2 compounds no matter whether ∠QXM2 is larger or smaller than 90°, and (ii) ∠XQM2 increases in the 1T-MX2 with ∠QXM2<90° but decreases in the 1T-MX2 with ∠QXM2 >90° (Supplementary Fig. 1). The changes in and , ∠M1XM2 and ∠M2XM3 and ∠XQM2 thus store the strain energy, which will be partially released in the subsequent third step relaxation.

The third-step relaxation determines the sign of Poisson’s ratio. The negative Poisson’s ratio of d2–d3 MX2 can be attributed to the strong t2g–p-orbital coupling. Such strong coupling implies a large amount of strain energy stored in the decreased ∠XQM2 after the second step. This part of strain energy will be released in this third step through atom M2 relaxing along the increased b-lattice direction, leading to a negative Poisson’s ratio. The strength of t2g–p-orbital coupling depends not only on the d-electron count of the transition metal but also on the chalcogen atom. This dependence explains why the Poisson’s ratio of the compounds from same d2 or d3 group also differs from one another as shown in Fig. 2a.

For d0–d1 MX2, the positive Poisson’s ratio results from the marginal or weak intermetal t2g coupling and t2g–p coupling. Such weak couplings imply that the strain energy stored in and and ∠XQM2 is also marginal or small. The major strain energy that can be released in the third step is thus stored in the increased ∠M1XM2 and ∠M2XM3. Therefore, it is energetically favourable that atom M2 relaxes in the b-decreasing direction, reducing the increase in ∠M1XM2 and ∠M2XM3, and resulting in a positive Poisson’s ratio. For d5–d6 MX2, the positive Poisson’s ratio originates from the fact that the t2g–p coupling aligns along the M–X bond and does not energetically affect the change in ∠XQM2. In other words, the strain energy stored in the decreased ∠XQM2 is small. Since the t2g antibonding is also generally weak, the relaxation of atom M2 is energetically favourable in the b-decreasing direction, giving rise to a positive Poisson’s ratio. This deformation mechanism is similar to that in d0–d1 compounds.

Simply saying, the negative Poisson’s ratio in d2–d3 MX2 results from the strong attractive coupling between the intermetal t2g-bonding states and the X p states, which prevents atoms X and M2 relaxing toward the ∠XQM2-increasing direction. The positive Poisson’s ratio arises from lack of such strong t2g–p coupling in other groups of 1T-MX2.

Discussion

The monolayer MX2 materials involve transition metals where strong correlation effects may be not well captured by the new strongly constrained and appropriately normed (SCAN) meta-GGA functional. To check the robustness of our results, we also calculated the Poisson’s ratio for 12 d2–d3 MX2 by using the HSE06 hybrid functional51. The results are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. It shows that the Poisson’s ratio of eight 1T-MX2 compounds (that is, MoSe2, MoTe2, WSe2, WTe2, TcTe2, ReS2, ReSe2, ReTe2) remains negative, whereas for other four compounds (that is, MoS2, WS2, TcS2, TcSe2) their Poisson’s ratio changes the sign from negative to slightly positive, which is still very interesting and useful for applications. Although it is found that the SCAN lattice constants agree better with experiment than the HSE06 ones for most of the compounds listed in this table, it is uncertain whether SCAN predicts a more accurate Poisson’s ratio than HSE06 since the semilocal SCAN functional could make larger density-driven error in the energy than HSE06 does for the system under stretching52. This uncertainty calls for experimental validation and further theoretical study. Nevertheless, the auxetic behaviour we find is robust in most of the d2–d3 MX2 compounds. The less negative Poisson’s ratio predicted by HSE06 (Supplementary Table 1) further indicates that the auxetic behaviour originates from the strong p–d coupling. In general, compared with the semilocal SCAN functional, HSE06 yields more localized metal d and chalcogen p orbitals and hence the weaker hybridization between them, which leads to less negative Poisson’s ratios in HSE06.

Our predicted in-plane auxetic behaviour is intrinsic in the 1T structure without any external engineering and occurs in the elastic region. This is different from the extrinsic auxetic behaviour reported in the epitaxial oxide thin-film53,54 and the engineered 2D materials, such as the wrinkled graphene55, graphane56 and borophane57. Recently, the negative Poisson’s ratio was also reported in metal nanoplates58, pristine graphene59 and semi-fluorinated graphene60. The negative Poisson’s ratio claimed there corresponds to the ratio calculated from νab=−∂ɛa/∂ɛb under large stains, differing from that calculated from νab=−ɛa/ɛb (the original definition of Poisson’s ratio) as we followed here. The Poisson’s ratios calculated from νab=−ɛa/ɛb for pristine graphene59 and semi-fluorinated graphene60 are actually both positive under a strain <∼15%, and for metal nanoplates, it is also positive under a strain <∼4%.

Finally, it is noteworthy that the auxetic behaviour of d2–d3 MX2 compounds is predicted in the high-symmetry 1T phase. This phase is known to be metastable or dynamically unstable in both d2 and d3 MX2 compounds44,61,62,63. However, experimentally, relevant phase diagrams of monolayer materials differ from those of bulk materials. The kinetic barriers between the different phases of monolayers may arise and be affected by many external factors, such as interfaces, underlying substrate, temperature, strain and impurities. Therefore, it is not uncommon to observe the undistorted 1T phase synthesized experimentally. For instance, although no kinetic barrier is found from first-principles calculations between the unstable 1T phase and dynamically stable distorted 1T phase, the undistorted 1T monolayer structures of MoS2, MoSe2, WS2 and WSe2 are observed from the exfoliation using Li-intercalation method45,64. For MoS2, the coexistence of 1T and 1H domains is also observed in the same monolayer46,47. Such heterogeneous monolayers with auxetic and non-auxetic domains are particularly intriguing since they could lead to novel functionality.

Methods

All calculations were performed using density functional theory and the plane-wave projector augmented-wave65 method as implemented in the VASP code66. The new SCAN meta-generalized gradient approximation was used67,68. SCAN is almost as computationally efficient as PBE-GGA functional, yet it often matches or exceeds the accuracy of the more computationally expensive hybrid functionals in predicting the geometries and energies of diversely bonded systems68. Supplementary Table 2 shows our calculated lattice constants for 1T-MX2 compounds. They agree very well with available experimental data44, especially for groups 4–7 1T-MX2 whose errors are within 1%. An energy cutoff of 500 eV was used. The monolayer structure is modelled in an orthorhombic supercell that contains two formula units (Fig. 1a) and a 20 Å vacuum space inserted in the out-of-plane direction. A 24 × 14 × 1 k-point grid was used to sample the Brillouin zone during structure relaxation. All atoms were fully relaxed until their atomic forces were <0.005 eV Å−1. The effects of spin-orbit coupling on the structural deformation are considered to be minor and hence not included in our study.

The Poisson’s ratio is calculated from the engineering strain (ɛ), which is defined as the change in length ΔL per unit of the original length L, that is, ɛ=ΔL/L. The applied uniaxial strain is realized in our calculations by fixing the lattice parameter to a value different from its equilibrium value during structural relaxation. The resulting strain in the transverse direction is extracted from the fully relaxed structure subjected to an applied strain.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Yu, L. et al. Negative Poisson’s ratio in 1T-type crystalline two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 8, 15224 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15224 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Evans, K., Nkansah, M. & Hutchinson, I. Molecular network design. Nature 353, 124 (1991).

Choi, J. & Lakes, R. Non-linear properties of metallic cellular materials with a negative Poisson’s ratio. J. Mater. Sci. 27, 5375–5381 (1992).

Lakes, R. & Elms, K. Indentability of conventional and negative Poisson’s ratio foams. J. Compos. Mater. 27, 1193–1202 (1993).

Choi, J. & Lakes, R. Fracture toughness of re-entrant foam materials with a negative Poisson’s ratio: experiment and analysis. Int. J. Fract. 80, 73–83 (1996).

Evans, K. E. & Alderson, A. Auxetic materials: functional materials and structures from lateral thinking!. Adv. Mater. 12, 617–628 (2000).

Greaves, G. N., Greer, A., Lakes, R. & Rouxel, T. Poisson’s ratio and modern materials. Nat. Mater. 10, 823–837 (2011).

Lakes, R. Foam structures with a negative Poisson’s ratio. Science 235, 1038–1040 (1987).

Scarpa, F. Auxetic materials for bioprostheses. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 25, 125–126 (2008).

Avellaneda, M. & Swart, P. J. Calculating the performance of 1–3 piezoelectric composites for hydrophone applications: an effective medium approach. J. Acoustical Soc. Am. 103, 1449–1467 (1998).

Choi, J. & Lakes, R. Design of a fastener based on negative Poisson’s ratio foam. Cell. Polym. 10, 205–212 (1991).

Sanami, M., Ravirala, N., Alderson, K. & Alderson, A. Auxetic materials for sports applications. Proc. Eng. 72, 453–458 (2014).

Huang, C. & Chen, L. Negative Poisson’s ratio in modern functional materials. Adv. Mater. 28, 8079–8096 (2016).

Lethbridge, Z. A., Walton, R. I., Marmier, A. S., Smith, C. W. & Evans, K. E. Elastic anisotropy and extreme Poisson’s ratios in single crystals. Acta Mater. 58, 6444–6451 (2010).

Milstein, F. & Huang, K. Existence of a negative Poisson ratio in fcc crystals. Phys. Rev. B 19, 2030 (1979).

Baughman, R. H., Shacklette, J. M., Zakhidov, A. A. & Stafström, S. Negative Poisson’s ratios as a common feature of cubic metals. Nature 392, 362–365 (1998).

Yeganeh-Haeri, A., Weidner, D. J. & Parise, J. B. Elasticity of a-cristobalite: a silicon dioxide with a negative Poisson’s kratio. Science 257, 650–652 (1992).

Ogi, H., Fukunaga, M., Hirao, M. & Ledbetter, H. Elastic constants, internal friction, and piezoelectric coefficient of α− TeO2 . Phys. Rev. B 69, 024104 (2004).

Williams, J. J., Smith, C. W., Evans, K. E., Lethbridge, Z. A. & Walton, R. I. Off-axis elastic properties and the effect of extraframework species on structural flexibility of the NAT-type zeolites: simulations of structure and elastic properties. Chem. Mater. 19, 2423–2434 (2007).

Gibson, L. J. & Ashby, M. F. The mechanics of three-dimensional cellular materials. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 382, 43–59 (1982).

Caddock, B. & Evans, K. Microporous materials with negative Poisson’s ratios. I. Microstructure and mechanical properties. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 22, 1877 (1989).

He, C., Liu, P. & Griffin, A. C. Toward negative Poisson ratio polymers through molecular design. Macromolecules 31, 3145 (1998).

Milton, G. W. Composite materials with Poisson’s ratios close to –1. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 40, 1105–1137 (1992).

Miki, M. & Murotsu, Y. The peculiar behavior of the Poisson’s ratio of laminated fibrous composites. JSME Int. J. Ser. 1 Solid Mech. Strength Mater. 32, 67–72 (1989).

Song, F., Zhou, J., Xu, X., Xu, Y. & Bai, Y. Effect of a negative Poisson ratio in the tension of ceramics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 245502 (2008).

Wojciechowski, K. Constant thermodynamic tension Monte Carlo studies of elastic properties of a two-dimensional system of hard cyclic hexamers. Mol. Phys. 61, 1247–1258 (1987).

Ortiz, A. U., Boutin, A., Fuchs, A. H. & Coudert, F.-X. Anisotropic elastic properties of flexible metal-organic frameworks: how soft are soft porous crystals? Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 195502 (2012).

Babaee, S. et al. 3D Soft metamaterials with negative Poisson’s ratio. Adv. Mater. 25, 5044–5049 (2013).

Schenk, M. & Guest, S. D. Geometry of Miura-folded metamaterials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 3276–3281 (2013).

Wei, Z. Y., Guo, Z. V., Dudte, L., Liang, H. Y. & Mahadevan, L. Geometric mechanics of periodic pleated origami. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 215501 (2013).

Silverberg, J. L. et al. Using origami design principles to fold reprogrammable mechanical metamaterials. Science 345, 647–650 (2014).

Rothenburg, L., Berlin, A. A. & Bathurst, R. J. Microstructure of isotropic materials with negative Poisson’s ratio. Nature 354, 470–472 (1991).

Baughman, R. H. & Galvão, D. S. Crystalline networks with unusual predicted mechanical and thermal properties. Nature 365, 735–737 (1993).

Lakes, R. Deformation mechanisms in negative Poisson’s ratio materials: structural aspects. J. Mater. Sci. 26, 2287–2292 (1991).

Jiang, J.-W. & Park, H. S. Negative Poisson’s ratio in single-layer black phosphorus. Nat. Commun. 5, 4727 (2014).

Du, Y. et al. Auxetic black phosphorus: a 2D material with negative Poisson’s ratio. Nano Lett. 16, 6701–6708 (2016).

Gomes, L. C., Carvalho, A. & Castro Neto, A. H. Enhanced piezoelectricity and modified dielectric screening of two-dimensional group-IV monochalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 92, 214103 (2015).

Han, J. et al. Negative Poisson’s ratios in few-layer orthorhombic arsenic: first-principles calculations. Appl. Phys. Express 8, 041801 (2015).

Mannix, A. J. et al. Synthesis of borophenes: anisotropic, two-dimensional boron polymorphs. Science 350, 1513–1516 (2015).

Zhang, S. et al. Penta-graphene: a new carbon allotrope. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 112, 2372–2377 (2015).

Yagmurcukardes, M. et al. Pentagonal monolayer crystals of carbon, boron nitride, and silver azide. J. Appl. Phys. 118, 104303 (2015).

Özçelik, V. O., Cahangirov, S. & Ciraci, S. Stable single-layer honeycomblike structure of silica. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 246803 (2014).

Wang, Y., Li, F., Li, Y. & Chen, Z. Semi-metallic Be5C2 monolayer global minimum with quasi-planar pentacoordinate carbons and negative Poisson’s ratio. Nat. Commun. 7, 11488 (2016).

Wang, Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kis, A., Coleman, J. N. & Strano, M. S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 699–712 (2012).

Wilson, J. & Yoffe, A. The transition metal dichalcogenides discussion and interpretation of the observed optical, electrical and structural properties. Adv. Phys. 18, 193–335 (1969).

Py, M. & Haering, R. Structural destabilization induced by lithium intercalation in MoS2 and related compounds. Can. J. Phys. 61, 76–84 (1983).

Eda, G. et al. Coherent atomic and electronic heterostructures of single-layer MoS2 . ACS Nano 6, 7311–7317 (2012).

Lin, Y.-C., Dumcenco, D. O., Huang, Y.-S. & Suenaga, K. Atomic mechanism of the semiconducting-to-metallic phase transition in single-layered MoS2 . Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 391–396 (2014).

Chhowalla, M. et al. The chemistry of two-dimensional layered transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets. Nat. Chem. 5, 263–275 (2013).

Yu, L., Ruzsinszky, A. & Perdew, J. P. Bending two-dimensional materials to control charge localization and Fermi-level shift. Nano Lett. 16, 2444–2449 (2016).

Stott, P. J., Mitchell, R., Alderson, K. & Alderson, A. A growth industry. Mater. World 8, 12–14 (2000).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Ruzsinszky, A., Perdew, J. P., Csonka, G. I., Scuseria, G. E. & Vydrov, O. A. Understanding and correcting the self-interaction error in the electrical response of hydrogen chains. Phys. Rev. A 77, 060502 (2008).

Sandiumenge, F. et al. Competing misfit relaxation mechanisms in epitaxial correlated oxides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 107206 (2013).

Aguirre-Tostado, F. et al. Elastic anomaly for Sr TiO3 thin films grown on Si (001). Phys. Rev. B 70, 201403 (2004).

Grima, J. N. et al. Tailoring graphene to achieve negative Poisson’s ratio properties. Adv. Mater. 27, 1455–1459 (2015).

Cadelano, E., Palla, P. L., Giordano, S. & Colombo, L. Elastic properties of hydrogenated graphene. Phys. Rev. B 82, 235414 (2010).

Kou, L. et al. Auxetic and ferroelastic borophane: a novel 2D material with negative Possion’s ratio and switchable dirac transport channels. Nano Lett. 16, 7910–7914 (2016).

Ho, D. T., Park, S.-D., Kwon, S.-Y., Park, K. & Kim, S. Y. Negative Poisson’s ratios in metal nanoplates. Nat. Commun. 5, 3255 (2014).

Jiang, J.-W., Chang, T., Guo, X. & Park, H. S. Intrinsic negative Poisson’s ratio for single-layer graphene. Nano Lett. 16, 5286–5290 (2016).

Qin, R., Zheng, J. & Zhu, W. Sign-tunable Poisson’s ratio in semi-fluorinated graphene. Nanoscale 9, 128–133 (2017).

Duerloo, K.-A. N., Li, Y. & Reed, E. J. Structural phase transitions in two-dimensional Mo-and W-dichalcogenide monolayers. Nat. Commun. 5, 4214 (2014).

Tongay, S. et al. Monolayer behaviour in bulk ReS2 due to electronic and vibrational decoupling. Nat. Commun. 5, 3252 (2014).

Fang, C., Wiegers, G., Haas, C. & De Groot, R. Electronic structures of, and in the real and the hypothetical undistorted structures. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 9, 4411 (1997).

Ambrosi, A., Sofer, Z. & Pumera, M. 2H→1T phase transition and hydrogen evolution activity of MoS2, MoSe2, WS2 and WSe2 strongly depends on the MX 2 composition. Chem. Commun. 51, 8450–8453 (2015).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Sun, J., Ruzsinszky, A. & Perdew, J. P. Strongly constrained and appropriately normed semilocal density functional. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 036402 (2015).

Sun, J. et al. Accurate first-principles structures and energies of diversely bonded systems from an efficient density functional. Nat. Chem. 8, 831–836 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank John P. Perdew for valuable scientific discussions and comments on the manuscript. We also thank Richard C. Remsing and Jefferson E. Bates for the comments on the manuscript. This research was supported as part of the Center for the Computational Design of Functional Layered Materials (CCDM), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences (BES), under Award #DE-SC0012575. This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. This research was also supported in part by the National Science Foundation through major research instrumentation grant number CNS-09-58854.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Y. designed the project, performed the calculations and wrote the manuscript. Q.Y. and A.R. contributed to analysing the results and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figure, Supplementary Tables and Supplementary References (PDF 238 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, L., Yan, Q. & Ruzsinszky, A. Negative Poisson’s ratio in 1T-type crystalline two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat Commun 8, 15224 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15224

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15224

This article is cited by

-

Prediction of nonlayered oxide monolayers as flexible high-κ dielectrics with negative Poisson’s ratios

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Multiferroicity and giant in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio in wurtzite monolayers

npj Computational Materials (2022)

-

Efficient prediction of temperature-dependent elastic and mechanical properties of 2D materials

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Understanding porosity and temperature induced variabilities in interface, mechanical characteristics and thermal conductivity of borophene membranes

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Predicting an ideal 2D carbon nanostructure with negative Poisson's ratio from first principles: implications for nanomechanical devices

Carbon Letters (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.