Abstract

Large amplitude variations in atmospheric CO2 were associated with glacial terminations of the Late Pleistocene. Here we provide multiple lines of evidence suggesting that the ∼20 p.p.m.v. overshoot in CO2 at the end of Termination 2 (T2) ∼129 ka was associated with an abrupt (≤400 year) deepening of Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). In contrast to Termination 1 (T1), which was interrupted by the Bølling-Allerød (B-A), AMOC recovery did not occur until the very end of T2, and was characterized by pronounced formation of deep waters in the NW Atlantic. Considering the variable influences of ocean circulation change on atmospheric CO2, we suggest that the net change in CO2 across the last 2 terminations was approximately equal if the transient effects of deglacial oscillations in ocean circulation are taken into account.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Late Pleistocene was characterized by large amplitude variations in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) with corresponding changes in temperature and ice volume1,2,3. The overall pattern of this glacial–interglacial (G–IG) variability is of a gradual build-up of ice sheets as atmospheric CO2 decreases over tens of thousands of years, followed by a relatively rapid collapse of ice sheets and rise in CO2 during deglaciation or glacial termination4. The last four glacial cycles (spanning the past ∼430 kyr) show a relatively uniform saw-tooth pattern of G–IG variability but the amplitude of CO2 change across their terminations is quite variable. For example, the change in atmospheric CO2 across the most recent deglaciation (Termination, T1) was ∼80 p.p.m.v. compared with a rise of ∼100 p.p.m.v. across T2 (refs 5, 6). Most recent attempts to explain the amplitude of G–IG CO2 variability call upon several distinct mechanisms or processes with variable (and often opposing) effects on CO2 (refs 7, 8). In principle therefore, variations in the relative timing of such changes across glacial terminations could give rise to differences in the apparent magnitude of deglacial CO2 change.

Changes in ocean circulation are thought to play a critical role in atmospheric CO2 variability9,10,11 and the process of deglaciation itself12,13,14,15 yet the timing of such changes across T2 is poorly constrained. By analogy with similar conditions associated with Heinrich Stadial 1 (HS1, ∼18–14.6 ka (ref. 15)) during the early part of T1, evidence from North Atlantic marine sediments16,17,18, Chinese speleothems12 and Antarctic ice cores1,13 has been used to infer that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) may have been in a weakened and or shallow mode throughout much of T2 (refs 12, 13; during a prolonged interval of North Atlantic cold identified as HS11, ∼135–129 ka (ref. 19)) with resumption to a deep and warm mode of circulation occurring only later (∼124–127 ka) within the penultimate interglacial period, Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 5e (refs 17, 18). Crucially, if this were the case, it would make T2 quite distinct from the most recent termination, which was characterized by two episodes of weakened AMOC (HS1 and the Younger Dryas (YD)), that were interrupted by an interval of invigorated circulation during the Bølling-Allerød (B-A)20,21,22.

Recently published records of seawater Nd isotopes (measured on bulk sediment leachates) and sedimentary Pa/Th from ODP Site 1063 retrieved from the NW Atlantic17 support the notion of a weakened AMOC during HS11 with a reactivation of North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) formation during MIS 5e. However, the lack of precise age control across T2, makes it difficult to assess the timing of this change with respect to the record of atmospheric CO2. Here we present new records of Nd isotopes measured on fossil fish debris (Methods section) together with benthic foraminiferal δ13C and δ18O from the same core (ODP Site 1063; 33.69° N, 57.62° W, 4,584 m water depth; Fig. 1). To further characterize environmental conditions across T2 and, crucially, to allow us to place our records within the chronostratigraphic framework of the ice-core records23 (Methods section) we also present new high resolution records of planktic foraminiferal δ18O (measured on Globorotalia inflata), planktic foraminiferal faunal abundance, ice rafted debris (IRD) counts, and additional carbonate preservation indices, all measured on the same samples from ODP Site 1063. In addition we present new sortable silt (SS) measurements (Methods section) from ODP Site 983 (60.48 N, 23.68 W, 1,984 m water depth), to assess the strength of deep water overflows (at that site) emanating from the Nordic Seas24. Our results suggest that the AMOC was supressed throughout HS11 with an abrupt resumption of northern deep water production ∼129 ka and recovery to a modern-like mode of AMOC by ∼124 ka. By comparison with T1 (which experienced a relatively early AMOC recovery associated with the B-A) we conclude that differences in the apparent magnitude of CO2 change across the last two terminations can be explained, at least in part, by differences in the sequence and timing of deglacial events and their relative influence on atmospheric CO2.

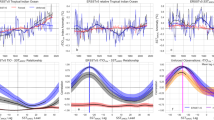

(a) Map of modern near-surface seawater Nd isotopic composition (Methods section). Stippled areas are regions of modern intermediate and deep water production. Locations of ODP sites 983 and 1063 are also indicated. (b,c) Station map and seawater Nd isotopic compositions from GEOTRACES section GA02 (ref. 26) highlighting that in the modern ocean only U-NADW (intermediate water) carries a very negative ɛNd fingerprint, derived from subduction of waters in the Labrador Sea (NW Atlantic Ocean). Overflow waters from the NE Atlantic Ocean, which form the pre-cursor water masses for L-NADW, carry a more radiogenic (higher ɛNd) fingerprint. DSOW is Denmark Strait Overflow Water. ODP site 983 is bathed by ISOW (not shown), which has a similar ɛNd composition to DSOW. Map and sections created using the ODV programme (Schlitzer, R., Ocean Data View, http://odv.awi.de, 2016).

Results

Surface ocean properties

Our new records of planktic foraminiferal δ18O, fauna and IRD counts (Fig. 2a) provide information on upper ocean conditions that we exploit for age model development (Methods section). The abundance record of cold adapted species (Neogloboquadrina pachyderma plus Neogloboquadrina incompta) reveals several intervals of colder surface conditions, which are also reflected by more positive planktic δ18O values and the presence of IRD. The records suggest that the interval assigned to HS11 experienced the coldest conditions within the period of interest, with the warmest conditions (as identified from the abundance of warm foraminiferal species: Globigerinoides ruber plus Globigerinoides sacculifer) being attained directly following HS11, during the earliest part of MIS 5e.

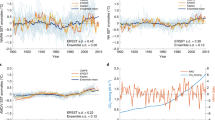

(a) (from top to bottom) Antarctic ice core temperature proxy, EDC (EPICA Dome C) δD (ref. 1); GLT_syn_hi, a proxy for anomalous northward heat transport associated with the bipolar seesaw (derived from EDC δD)13; atmospheric CH4 from EDC (ref. 69; all other records are from ODP 1063) planktonic δ18O measured on G. inflata; percentage of warm foraminiferal species (see text); percentage of cold water species; number of IRD grains g−1; implied sedimentation rate. Filled blue and red circles are tuning points between site 1063 and CH4 and or GLT_syn_hi, respectively (Methods section). (b) (from top to bottom); planktonic δ18O; seawater ɛNd (pink symbols were measured by TIMS, purple by MC-ICP-MS, grey are results of ref. 17, error bars are 2σ, arrow is modern value at 1063); percentage of foraminiferal fragmentation; percentage of coarse (>63 μm) fraction; benthic δ13C (C. wuellerstorfi with 3 point running mean); benthic δ18O (C. wuellerstorfi, M. pompilioides (−0.15; Methods section) and O. umbonatus (−0.38)). Blue vertical boxes are cold intervals, pink box is our inferred overshoot of the AMOC.

We tie the sharp warming at the end of HS11 in our records to the sharp increase in atmospheric CH4 at ∼128.7 ka (128.9–128.5 ka) on the ice-core timescale, AICC2012 (ref. 23; Methods section; Fig. 2a). This age estimate is in good agreement with other recent studies. For example, Jiménez-Amat and Zahn19 derive an age of 128.73 ka for an abrupt warming recorded in the Alboran Sea following HS11 by correlation to an Italian speleothem record. Another recent study based on an alternative age modelling strategy placed the end of HS11 at 130±2 ka (ref. 25). For comparison the 1σ uncertainty of the AICC2012 timescale at 128.7 ka is ±1.7 kyr (ref. 23). The most precise date attained for the implied shift from weak to strong Asian Monsoon rainfall associated with the end of HS11 is 129.0±0.1 ka, derived from a speleothem collected in Sanbao Cave, China12.

Changes in deep-ocean water mass structure

Modern bottom water at ODP Site 1063 has a Nd isotopic composition (expressed as ɛNd, the deviation of the measured 143Nd/144Nd ratio from the chondritic uniform reservoir in parts per 10,000) of ∼−13, reflecting the exported mixture of deep waters formed in the eastern and western North Atlantic (NADW) and those emanating from the Southern Ocean26 (Fig. 1). In agreement with ref. 17 we reconstruct significantly less negative values (ɛNd>−11) at the end of MIS 6 and throughout HS11 (Fig. 2b). In the modern ocean, less negative ɛNd values are characteristic of deep waters emanating from the south but also those derived from wintertime convection in the Nordic Seas (Fig. 1). Thus the record of ɛNd from ODP Site 1063 cannot be interpreted as a simple proxy for the mixing ratio between northern and southern deep water sources even if the ɛNd composition of the various deep water end-members remained constant27. On the other hand these deep water masses can be differentiated by their very different δ13C signatures and carbonate ion concentrations, with northern deep water masses being better ventilated (higher δ13C and [CO3=]) than their southern counterparts20,28. The low values of benthic δ13C and poor carbonate preservation (low % coarse fraction and high fragmentation) we observe during HS11 (Fig. 2b), in combination with less negative ɛNd values, therefore suggest an enhanced influence of southern-sourced deep waters (glacial equivalent to modern Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW)) in the abyssal North Atlantic during HS11 relative to today. This is analogous to the millennial-scale cold events of the last glacial cycle29. We note that our new record of benthic δ13C shows considerably more scatter than might be expected for an epifaunal species such as Cibicidoides wuellerstorfi, an observation that has also been made for other δ13C records from this region30 and more widely18. While this scatter is difficult to explain, it is possibly due to a fluctuating supply of organic material to the seafloor, occasionally overprinting the bottom water signal. Following previous studies18 we therefore apply a running mean (3 point) to the benthic δ13C record from ODP Site 1063.

Our records reveal a shift towards higher benthic δ13C and better preservation at the same time as surface ocean warming following HS11 (Fig. 2) suggesting the incursion of better ventilated deep waters to the abyssal North Atlantic likely in response to the renewed penetration of northern-sourced deep waters at this time. Although the absolute value of benthic foraminiferal δ13C can be influenced by whole-ocean changes in δ13C, as well as local effects due to organic matter respiration, the convergence between our new record from ODP Site 1063 (4,584 m) and that from intermediate depth ODP Site 983 (1,984 m)18 from the relatively remote NE Atlantic (Fig. 3b) suggests that a switch from a glacial to an interglacial-like mode of AMOC28 occurred at the start of MIS 5e. In combination with a pronounced peak in carbonate preservation at this time, as compared with the latter part of MIS 5e (Fig. 2), these observations are reminiscent of the extreme deepening and overshoot of the AMOC associated with the B-A during T1 (refs 20, 31, 32). Importantly our findings confirm that there was no equivalent to the B-A (or YD) during T2 (ref. 33), although there is evidence for a millennial-scale cooling event directly following our inferred overshoot of the AMOC ∼124–125 ka (ref. 34) and supported here by the record of benthic δ13C from ODP Site 1063 (Fig. 2b).

(a) (from top to bottom) IRD (grains.g−1; black and grey curves are on linear and log scales, respectively) and %NPS (reflecting surface temperature, blue and red curves are on linear and log scales, respectively) from NE Atlantic ODP site 983 (ref. 39; 60.4° N, 23.6° W, 1,984 m water depth); percentage of warm planktic foraminifera from ODP 1063; synthetic Greenland temperature record13; calculated gross freshwater flux due to melting continental ice sheets25. (b) (from top to bottom) ɛNd from ODP 1063 (NW Atlantic, purple symbols this study, grey symbols from ref. 17); SS mean grain size from ODP 983 (NE Atlantic, error bars are 1σ); benthic foraminiferal δ13C; benthic foraminiferal δ18O; reconstructed sea level3. Pink box represents inferred overshoot of AMOC during early MIS 5e, blue boxes represent the period of weakened circulation during HS11.

Changes in the locus of formation of Atlantic deep water

A deepening of NADW at the onset of MIS 5e could also be inferred from the shift to more negative seawater ɛNd values at this time17 (Fig. 2b). However, unlike the equivalent change obtained for the B-A (ref. 21), the very negative ɛNd values (<−15) attained during early MIS 5e demand a different deep water mass configuration relative to that of the present-day North Atlantic, and a source of bottom water with no modern analogue. At present, NADW represents a predominant mixture of deep waters formed in the NE Atlantic (overflows from the Nordic Seas) and the NW Atlantic (Labrador Sea; Fig. 1). Being colder and saltier than their western counterparts, deep waters produced in the Nordic Seas form so-called Lower- and Middle-NADW (summarized here as L-NADW). Today these waters occupy depths below ∼2,500 m at ODP Site 1063, and are characterized by a Nd isotopic composition of −12.4±0.4 (ref. 26). On the other hand wintertime convection in the Labrador Sea produces relatively warm and fresh Labrador Sea Water (LSW), which forms the upper component of NADW (U-NADW), and carries a Nd isotope fingerprint of ɛNd=−14.2 ±0.3 (at its extreme)26. At 4,584 m water depth, ODP Site 1063 lies within L-NADW, with only minor influence from colder and fresher AABW, and well outside the density range of LSW (Fig. 1). An obvious way of making the Nd isotopic composition of bottom waters at the site of ODP Site 1063 more negative would be to increase the influence of the very negative ɛNd surface waters found in the NW Atlantic (Baffin Bay and the Labrador Coast; Fig. 1). However, simply increasing the (volumetric) contribution of modern LSW to NADW, or increasing the Nd concentration in LSW17, is not sufficient to explain the negative values we observe at our site during early MIS 5e.

Surface waters with sufficiently negative Nd isotopic compositions (ɛNd<<−14) are observed north and south of the modern convection areas in the Labrador Sea and it is feasible that convection during early MIS 5e was shifted to a more southerly location compared to today, tapping into surface waters with more negative Nd isotopic composition. It is also possible that retreat of the North American ice sheet increased the weathering and supply of old continental material (with very negative ɛNd) to a broader area of the surface NW Atlantic. Irrespective of the exact location of convection though our results suggest that AMOC recovery following HS11 was accomplished (at least in part) by a drastic deepening of deep waters formed in the NW Atlantic. Similarly negative ɛNd values have been documented at the location of ODP site 1063 during the early Holocene21,35. In particular, Howe et al.35 conclude that these very negative early Holocene ɛNd values might reflect the ‘re-labelling’ of deep waters in the Labrador Sea by interaction with particularly un-radiogenic sediments, followed by their southward advection to abyssal depths. A key question remains as to whether these deep waters originated in the NW or NE Atlantic.

Results from an Earth System Model experiment (run in coarse resolution)36 suggest that convection in the South Labrador Sea could reach depths of 3,000–4,000 m during an abrupt deepening (and overshoot) of the AMOC following a period of weakened overturning (at least under glacial boundary conditions). Results of that experiment suggest that an overshoot of the AMOC occurs due to the accumulation of heat and salt in the intermediate depth tropical Atlantic, which enters the South Labrador Sea and induces hydrostatic instabilities. Such an increase in salinity would result in greater densities that could help displace colder southern-sourced deep waters and reinvigorate the northern cell of the AMOC. In this respect the initiation of deep water convection in the NW Atlantic could effectively act as the trigger for AMOC resumption more broadly. However, we note that the simulated overshoot is only a transient (decadal) feature of the model simulation whereas the negative spike we observe in ɛNd lasts for thousands of years.

Our results require that deep waters formed in the NW Atlantic were dense enough (at least relative to other deep waters present at that time) to influence the deepest parts of the Atlantic basin throughout the earliest part of MIS 5e. This would be possible only if other sources of deep water (which today represent the densest waters within the Atlantic) were diminished or possessed lower densities than those forming in the NW Atlantic. Indeed, a partial solution to this conundrum is hinted at by a recent proxy reconstruction from the Southern Ocean37, which suggests that the formation and or density of AABW around Antarctica was greatly reduced across the same interval as we invoke enhanced deep-water formation in the NW Atlantic.

Furthermore, evidence from the deep NE Atlantic suggests that deep water formation in the Nordic Seas and its overflow into the Atlantic as L-NADW may not have resumed its typical interglacial mode until ∼124 ka (ref. 18). Our new SS measurements from ODP Site 983 (situated on the Gardar Drift, southeast of Iceland) provide further insight into this possibility (Fig. 3). SS mean grain size of the terrigenous fraction of marine sediments can be used as a proxy for the flow speed of bottom currents38. The site of ODP Site 983 is sensitive to the overflow of dense waters formed in the Nordic Seas across the Iceland-Scotland Ridge (so-called Iceland-Scotland Overflow Water (ISOW)), an important pre-cursor to L-NADW. Our new record of SS shows a strong increase ∼124 ka, much later than our inference of AMOC recovery via deep water formation in the NW Atlantic ∼129 ka. While the record of SS from a single water depth cannot tell us about the gross flux of ISOW it is nevertheless instructive. For example, a depth transect of SS records from the same region (including site 983) covering the Holocene24 reveals a gradual deepening and strengthening of ISOW over the course of the early Holocene, with maximum inferred flow speeds (highest SS) at the site of ODP Site 983 being attained ∼7 ka, when the ISOW was inferred to have reached its present-day depth and maximum net strength. By analogy (and acknowledging the limitations of a single core site) we infer from our record that ISOW strengthened, and or deepened (becoming denser with respect to surrounding water masses) ∼124 ka.

In Fig. 3a we show surface records from ODP Sites 983 (ref. 39) and 1063 (this study). Both records suggest an abrupt warming of the surface ocean ∼129 ka but while site 1063 experienced its warmest temperatures during early MIS 5e, the record from site 983 suggests that optimum conditions were not attained until ∼124 ka towards the northeast. A similar finding was reported previously40,41 and interpreted as the delayed recovery of a full interglacial mode of circulation, with reduced inflow of warm waters to the Nordic Seas via the North Atlantic Current during early MIS 5e. The sustained occurrence of ice rafting in the high latitude North Atlantic until ∼124 ka is evidenced by the record of IRD from ODP Site 983 (ref. 39; Fig. 3a) as well as previous studies in the Nordic Seas41. Correspondingly fresher conditions across the Nordic Seas and NE Atlantic could explain the decrease in formation and or density of ISOW during early MIS 5e (ref. 18) and the resultant density ‘vacuum’42 that may have allowed NW Atlantic deep waters to reach abyssal depths.

Rapidity of deep ocean change

Thanks to its high temporal resolution our new record of benthic foraminiferal δ18O provides further evidence for the timing and rapidity of ocean circulation change at the onset of MIS 5e in the NW Atlantic (Figs 2 and 3). The record reveals a very large (0.90±0.14‰) and abrupt decrease in δ18O at the same time as we observe surface ocean warming at the end of HS11. The transition takes place in <400 year (occurring between two samples, Methods section) and occurs after the main phase of deglacial sea-level rise3 (Fig. 3b), hence it cannot be explained simply by a whole-ocean change in δ18O. More likely it reflects a change in water mass geometry and the relative dominance of water masses with very different temperature/salinity characteristics within the abyssal North Atlantic. Equally rapid changes in deep ocean circulation in the same area across MIS 5e/d were reported previously43.

Changes in benthic foraminiferal δ18O can reflect changes both in bottom water temperature and the oxygen isotopic composition of seawater (δ18Osw or δw), which is related to salinity44. The most recent calibration for the temperature sensitivity of cosmopolitan benthic foraminifera is −0.25‰ per °C for cold waters45 so a shift of −0.90‰ in benthic foraminiferal δ18O implies a warming of 3.6 °C given no change in δw. Modern deep waters formed in the Southern Ocean are fresher and have lower δw than more northerly intermediate waters (the modern offset in δw between AABW and U-NADW is ∼0.5‰ (ref. 44)). If the observed shift in benthic foraminiferal δ18O ∼129 ka reflected a change from an equivalent of modern AABW to modern U-NADW the net shift of −0.90‰ would require a warming of 5.6 °C, which is similar to the modern temperature difference between AABW and LSW. On the other hand, pore water studies suggest that glacial-age (MIS 2) southern deep waters may have been significantly more saline (with higher δw by 0.12–0.42‰) than northern water masses46. It is not possible to know at this stage whether such values would be applicable to the transition from MIS 6 to MIS 5e, but if they were then a shift from southern to northern deep water masses would require a temperature increase of 1.9–3.1 °C to produce a net change of −0.90‰ in benthic δ18O. Furthermore, since the deglacial rise in sea level across T2 was only just complete by 129 ka (refs 3, 25; Fig. 3b) it is entirely feasible that the corresponding change in δw had not fully penetrated to all parts of the ocean interior47. If the deglacial evolution of δw in southern-sourced deep waters lagged behind that of northern sources this could also have contributed to the sharp decrease in benthic δ18O we observe ∼129 ka as the influence of southern waters gave way to those originating from the north.

Another possible mechanism that could explain the shift towards lighter benthic δ18O, as well as the very negative ɛNd values ∼129 ka without invoking subsidence of a ‘low density’ water mass, is the formation of dense brines possibly through wind action over coastal polynyas in Baffin Bay (analogous to those formed around modern-day Antarctica and within the Arctic Ocean48), perhaps as a result of anomalous wind patterns during the earliest part of MIS 5e. However a number of studies suggest that dissolved inorganic carbon is preferentially rejected relative to alkalinity during brine formation, possibly as a result of CaCO3 precipitation and subsequent entrapment within the sea ice matrix while aqueous CO2 escapes e.g. ref. 49. This would have the effect of decreasing the carbonate saturation state of deep waters formed in this way and consequently we might not expect to observe enhanced preservation at the site of ODP Site 1063 during early MIS 5e (Fig. 2b) if deep waters at the site were being formed through brine rejection. Notwithstanding, the possibility that brine formation may have contributed to the negative ɛNd values we observe deserves further consideration.

Deglacial rise in atmospheric CO2

Changes in ocean circulation can influence atmospheric CO2 in multiple ways8,9,10,11. The records of atmospheric CO2 and ocean circulation (as inferred from North Atlantic Nd isotopes) across the last two glacial terminations are shown in Fig. 4. The contrast between glacial (low CO2) and interglacial (high CO2) conditions has led to a plethora of hypotheses as to the mechanisms controlling atmospheric CO2 on orbital timescales (see ref. 8 for a summary) with an overall consensus that changes in the oceanic storage of carbon (through synergistic interactions between physical, chemical and biological processes) are the most important. But of relevance to this study are the transitions themselves between glacial and interglacial state, which appear to proceed through mechanisms operating on sub-millennial to millennial timescales.

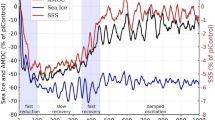

Records of (from top to bottom) Antarctic temperature (δD proxy)1, atmospheric CO2 (refs 2, 5, 6), seawater ɛNd (ref. 21 and this study) and atmospheric CH4 (ref. 69). Blue boxes are intervals of weakened and/or shallow AMOC; pink box encompasses the deglacial change in CO2 across T1. YD, HS1 and HS11 are Heinrich stadials. CO2 record across T1 is from ref. 5 on the WDC06A-7 timescale. CO2 records across T2 are from ref. 6 (dark green) and ref. 2 (light green), both on the AICC2012 timescale23. CH4 records are both on the AICC2012 timescale.

Atmospheric CO2 increased over several discrete intervals across T1 (ref. 5; Fig. 4). During times of weakened and/or shallow AMOC (HS1 and the YD) CO2 increased relatively gradually (∼10 p.p.m.v. kyr−1). This may be contrasted with two distinctly more abrupt increases (∼10–15 p.p.m.v. in 100–200 years) that occurred on recovery to a stronger mode of AMOC following HS1 and the YD50. In fact the cycle of gradually rising CO2 during times of particularly weak or shallow AMOC (HS events), followed by an abrupt increase on recovery is not unique to glacial terminations and is observed repeatedly throughout the last glacial period. For example, the transition from HS4 into Dansgaard-Oeschger (D-O) event 8 was marked by an abrupt increase in atmospheric CO2 of ∼10 p.p.m.v. (ref. 51) as the AMOC deepened20. A similar pattern marked the end of HS5 and the onset of D-O events 19–21 (refs 17, 52, 53). Previous studies suggest that enhanced vertical mixing within the Southern Ocean during times of reduced AMOC54,55, combined with a replacement of NADW by AABW (which has a higher pre-formed nutrient content) could promote the gradual rise in CO2 at these times11,56. In addition, a reduction in northern hemisphere land vegetation due to a southward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone could contribute to CO2 rise during times of weakened AMOC10.

The much more rapid increases in atmospheric CO2 following HS1 and the YD (and presumably equivalent events during MIS 3) are thought to be linked to resumption of the AMOC5,50, possibly a result of the fast changes in solubility (as a function of temperature and salinity) associated with AMOC recovery9 and the flushing of respired carbon from the deep ocean as the AMOC deepens20. Rapid thawing of boreal permafrost and increased respiration of soil-bound carbon stocks could have provided an additional source of carbon at these times57. The subsequent and more gradual decrease in CO2 observed while the AMOC is in a strong mode is thought to reflect the reversal of processes driving its increase during intervals of weakened circulation11. Thus the abrupt rise in atmospheric CO2 associated with a strengthening of AMOC is only a transient feature, reflecting the different timescales of the mechanisms involved (for example, the rapid effects of decreased solubility9 and deep ocean flushing20 driving up CO2, in contrast to the subsequent build-up of regenerated carbon in the deep ocean11 driving CO2 back down).

The close relationship between atmospheric CO2 and the AMOC described above suggests that when ocean circulation is in quasi equilibrium (which arguably is the case only during full interglacial and full glacial conditions13,58) then CO2 should remain (approximately) constant. Of course, additional drivers such as carbonate compensation (for example, during the Holocene59) and fossil fuel burning (e.g. within the Anthropocene) may affect CO2 independently of ocean circulation on a variety of timescales.

Building on these arguments we now compare the last two terminations (Fig. 4). Atmospheric CO2 increased during the intervals of weak/shallow AMOC associated with HS1 and the YD (T1) and HS11 (T2). Following the continuous rise in CO2 throughout HS11 a transient maximum was attained on recovery and (inferred) overshoot of the AMOC during early MIS 5e, after which CO2 stabilized at an interglacial level as the AMOC resumed its interglacial mode by ∼124 ka. In contrast, the transient maximum in atmospheric CO2 associated with the B-A occurred within its overall deglacial rise across T1 and its effect is therefore obscured (essentially discounted) within the net change in CO2. Moreover, the abrupt rise in CO2 associated with AMOC recovery following the YD was apparently smaller than that following HS11 (perhaps reflecting the shorter duration of the YD) and in combination with the very long duration of HS11 the overall change in CO2 across T2 was larger (by ∼20 p.p.m.v.) than that across T1. On the other hand, allowing for the transient maxima in CO2 associated with AMOC recovery, the net change in CO2 between glacial and interglacial conditions was actually quite similar across both terminations (Fig. 4). We therefore suggest that the apparently larger increase in CO2 across T2, as compared with T1 was a result of the long-lasting AMOC perturbation associated with HS11 and consequently its late resumption at the beginning of MIS 5e. Note that we do not know how or if the location of AMOC resumption (NW versus NE Atlantic) may affect the magnitude of the transient maximum in CO2. Our arguments here revolve around the timing of recovery only. We also acknowledge that the majority of our discussion is based on findings from a single core site in the NW Atlantic. Future validation of our results will require equivalent reconstructions from a variety of sites across a much broader region.

A final question concerns why there was no YD-like event during T2. It is thought that recovery of the AMOC during deglaciation may occur with the cessation of freshwater release across the North Atlantic31 or in response to more gradual global warming, in which case the addition of freshwater may still act to delay resumption32. The lack of an early recovery during T2 could therefore reflect the larger insolation forcing and faster ice sheet retreat associated with the penultimate termination33, providing a sustained supply of freshwater to regions of deep water formation and delaying resumption of the AMOC until atmospheric CO2 had reached its interglacial level.

Methods

Sample preparation

ODP Site 1063 core was resampled every 4 cm along the shipboard splice across the interval of interest. Sediment core samples were washed and sieved to 63 μm before drying and weighing. Planktonic foraminiferal species and fragment counts were performed on splits of the >150 μm fraction containing ∼300 individual tests. Per cent fragmentation is calculated following Le and Shackleton60. Stable isotopes were measured on the planktic species G. inflata picked from the 300 to 355 μm fraction. Due to very low abundances of benthic foraminifera, 3 species (C. wuellerstorfi, Melonis pompilioides and Oridorsalis umbonatus, all picked from >150 μm and analysed individually) were used to obtain a more complete record. Measurements were performed at Cardiff University stable isotope facility using a Thermofinnigan MAT-252 mass spectrometer (long-term external reproducibility better than ±0.08‰ for δ18O and ±0.03‰ for δ13C) for benthic samples and a Delta Advantage V (long-term external reproducibility ±0.1‰ for δ18O) for planktics. Offsets in δ18O between benthic species were accounted for by correcting to C. wuellerstorfi by subtracting the average offset between species as measured in samples where multiple species were present (M. pompilioides −0.15‰, O. umbonatus −0.38‰). All results are reported within Supplementary Data 1.

Fossil fish teeth and debris

Fossil fish teeth and debris were handpicked from the >63 μm sediment fraction of 91 samples at ODP Site 1063 between 34.0 and 39.9 metres composite depth (mcd). To obtain enough material for Nd isotope analyses, up to five samples were combined as indicated in Supplementary Data 1. The teeth and debris were cleaned with ultrapure Milli-Q water (18.2 MΩ water) and methanol (that is, no reductive and oxidative cleaning), following61. Samples were digested in 2M HCl, dried down, converted to nitrate from and subjected to a standard two-stage ion chromatography procedure in the MAGIC clean room laboratories at Imperial College London. In brief, Eichrom TRU-Spec resin (100–120 μm bead size) was utilized to isolate the REEs from the sample matrix and Eichrom LN-Spec resin (50–100 μm bead size) was utilized to separate Nd from the other REEs (slightly modified after ref. 62).

Neodymium isotope ratios

Neodymium isotope ratios were measured on a Nu Plasma HR MC-ICP-MS and a Thermo Scientific Triton TIMS at the MAGIC Laboratories at Imperial College London. Measurements on the MC-ICP-MS were carried out in static mode, using a 146Nd/144Nd ratio of 0.7219 to correct for instrumental mass bias following the exponential law. 144Sm interferences can be adequately corrected if the 144Sm contribution is <0.1% of the 144Nd signal, which was the case for all samples. Measured 143Nd/144Nd ratios of the JNdi standard yielded ratios of 0.512133±0.000013 (2SD, n=8) and 0.512056±0.000015 (2SD, n=27) during two separate sessions. Measurements on the Thermal Ionisation Mass Spectrometer (TIMS) were carried out as Nd oxides (NdO+) following the method outlined by Crocket et al.63, yielding JNdi 143Nd/144Nd ratios of 0.512101±0.000007 (2SD; n=5). Accuracy was achieved by correcting all sample results from both machines to the published JNdi 143Nd/144Nd ratio of 0.512115 ±0.000007 (ref. 64), and confirmed with USGS rock standard BCR-2 results on both machines, which were within error of the recommended value by Weis et al.65 Comparability between both machines was furthermore demonstrated by excellent agreement of duplicate measurements for four samples (Supplementary Data 1). Procedural blanks were consistently below 10 pg Nd.

The data used to create the (sub)surface map of seawater Nd isotopic compositions in the North Atlantic (Fig. 1a) were assembled from the compilation by van de Flierdt et al.27 For each available station, Nd isotope results for the uppermost water depth were utilized if this depth was <65 m. One exception was made in the Labrador Sea, where a measurement from 100 m depth was included. For the Baffin Bay area north of the shallow sill separating it from the Labrador Sea, data from the entire water column were integrated. All stations utilized for the compilation are indicated by small black dots on the (sub)surface ɛNd map. Station locations from the northern part of the GEOTRACES transect GA02, sampled for dissolved Nd isotopes, are indicated by black circles on the small map (Fig. 1b). Water depths for all Nd samples are indicated by small black dots on the section (Fig. 1c).

Age model development

Since we wish to compare our records directly with those from ice cores we need to refine earlier versions of the age model for ODP Site 1063 across T2 that were based on orbital and paleomagnetic approaches66,67. In a recent study52 we derived an age model for the same core across the MIS 5a/4 boundary by tuning between a high resolution record of planktic δ18O (measured on G. inflata) and the Greenland ice core temperature record. Abrupt shifts in planktic δ18O (including for G. inflata) in the Northwest Atlantic are thought to have been synchronous to the shifts in Greenland ice core δ18O across Termination 1 and throughout MIS 3 (refs 22, 68). Although planktic δ18O from the subtropical Northwest Atlantic during D-O events likely contains both temperature and salinity signals, the ‘raw’ planktic δ18O appears in-phase with Greenland climate, at least on multi-centennial and longer timescales52. Moreover, our planktic foraminifer species count records share many similarities with the isotope record (Fig. 2) and we use these to support our tuning strategy. Because the Greenland record does not encompass Termination 2 we instead use the record of atmospheric methane from Antarctica69 on the AICC2012 timescale23 as a tuning target, supplemented by the synthetic record of Greenland temperature variability, GLT_syn13. Sharp increases in CH4 are consistently aligned (within ∼60 year) with rapid shifts in Greenland temperature during the last 120 kyr (ref. 70).

Age uncertainties in our approach derive from the precision of alignment between the various records and the absolute uncertainty of the ice core age model. Because we are here interested in the relative timing of marine events with respect to the ice core record our error analysis does not consider the additional uncertainty of the ice core chronology. In the case of the implied resumption of deep overturning circulation following HS11, we note that the −0.9‰ shift in benthic δ18O occurs across the same interval (between two samples, that is, within 400 year or within 300 year if our tie-point is placed at the end of the transition instead of midway through) as the warming implied by our planktic δ18O and faunal records at the end of the HS11, which we tie to the abrupt rise in CH4 at ∼128.7 ka (Fig. 2). The abrupt increases in both CH4 and CO2 at this time occurred in parallel between 128.9 and 128.5 ka on the AAIC2012 age model2,23. Therefore because we make the assumption of synchronicity between surface ocean temperature variability and northern hemisphere climate, as reflected by CH4 and GLT_syn, we estimate that that the recovery of deep overturning circulation within the North Atlantic was synchronous with the abrupt rise in CO2 to within 400 year (the width of the transitions in CO2, CH4 and benthic δ18O).

Sortable silt measurements

Samples from ODP Site 983 were prepared for SS analysis following established protocols24,38. Briefly, 2–4 g of bulk fine fraction (<63 μm) was treated with acetic acid and sodium carbonate to remove carbonate and biogenic silica, respectively. The residual silicate fraction was treated with Calgon and ultrasonicted for 4 min before analysis on a Beckman Coulter Multisizer 3 coulter counter. At least two replicate measurements of the arithmetic mean calculated from the differential volume of grains within the 10–63 μm terrigenous silt fraction are reported for each sample depth. The average s.d. between replicate measurements for all samples is ±0.23 μm.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Additional information

How to cite this article: Deaney, E. L. et al. Timing and nature of AMOC recovery across Termination 2 and magnitude of deglacial CO2 change. Nat. Commun. 8, 14595 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14595 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Jouzel, J. et al. Orbital and millennial Antarctic climate variability over the past 800,000 years. Science 317, 793–796 (2007).

Bereiter, B. et al. Revision of the EPICA Dome C CO2 record from 800 to 600 kyr before present. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 542–549 (2015).

Grant, K. M. et al. Sea-level variability over five glacial cycles. Nat. Commun. 5, 5076 (2014).

Broecker, W. S. & van Donk, J. Insolation changes, ice volumes and the O18 in deep-sea cores. Rev. Geophys. Space Phys. 8, 169–198 (1970).

Marcott, S. A. et al. Centennial-scale changes in the global carbon cycle during the last deglaciation. Nature 514, 616–619 (2014).

Lourantou, A., Chappellaz, J., Barnola, J.-M., Masson-Delmotte, V. & Raynaud, D. Changes in atmospheric CO2 and its carbon isotopic ratio during the penultimate deglaciation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 1983–1992 (2010).

Kohler, P., Fischer, H., Munhoven, G. & Zeebe, R. E. Quantitative interpretation of atmospheric carbon records over the last glacial termination. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 19, doi: 10.1029/2004GB002345 (2005).

Sigman, D. M., Hain, M. P. & Haug, G. H. The polar ocean and glacial cycles in atmospheric CO2 concentration. Nature 466, 47–55 (2010).

Marchal, O., Stocker, T. F. & Joos, F. Impact of oceanic reorganizations on the ocean carbon cycle and atmospheric carbon dioxide content. Paleoceanography 13, 225–244 (1998).

Menviel, L., Timmermann, A., Mouchet, A. & Timm, O. Meridional reorganizations of marine and terrestrial productivity during Heinrich events. Paleoceanography 23, doi: 10.1029/2007PA001445 (2008).

Schmittner, A. & Galbraith, E. D. Glacial greenhouse-gas fluctuations controlled by ocean circulation changes. Nature 456, 373–376 (2008).

Cheng, H. et al. Ice age terminations. Science 326, 248–252 (2009).

Barker, S. et al. 800,000 years of abrupt climate variability. Science 334, 347–351 (2011).

Broecker, W. S. & Denton, G. H. The role of ocean-atmosphere reorganizations in glacial cycles. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 53, 2465–2501 (1989).

Barker, S. et al. Interhemispheric Atlantic seesaw response during the last deglaciation. Nature 457, 1097–1102 (2009).

Oppo, D. W., Horowitz, M. & Lehman, S. J. Marine core evidence for reduced deep water production during Termination II followed by a relatively stable substage 5e (Eemian). Paleoceanography 12, 51–63 (1997).

Böhm, E. et al. Strong and deep Atlantic meridional overturning circulation during the last glacial cycle. Nature 517, 73–76 (2015).

Hodell, D. A. et al. Surface and deep-water hydrography on Gardar Drift (Iceland Basin) during the last interglacial period. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 288, 10–19 (2009).

Jiménez‐Amat, P. & Zahn, R. Offset timing of climate oscillations during the last two glacial‐interglacial transitions connected with large‐scale freshwater perturbation. Paleoceanography 30, 768–788 (2015).

Barker, S., Knorr, G., Vautravers, M., Diz, P. & Skinner, L. C. Extreme deepening of the Atlantic overturning circulation during deglaciation. Nat. Geosci. 3, 567–571 (2010).

Roberts, N. L., Piotrowski, A. M., McManus, J. F. & Keigwin, L. D. Synchronous deglacial overturning and water mass source changes. Science 327, 75–78 (2010).

McManus, J. F., Francois, R., Gherardi, J. M., Keigwin, L. D. & Brown-Leger, S. Collapse and rapid resumption of Atlantic meridional circulation linked to deglacial climate changes. Nature 428, 834–837 (2004).

Bazin, L. et al. An optimized multi-proxy, multi-site Antarctic ice and gas orbital chronology (AICC2012): 120-800 ka. Clim. Past 9, 1715–1731 (2013).

Thornalley, D. J. R. et al. Long-term variations in Iceland–Scotland overflow strength during the Holocene. Clim. Past 9, 2073–2083 (2013).

Marino, G. et al. Bipolar seesaw control on last interglacial sea level. Nature 522, 197–201 (2015).

Lambelet, M. et al. Neodymium isotopic composition and concentration in the western North Atlantic Ocean: results from the GEOTRACES GA02 section. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 177, 1–29 (2016).

van de Flierdt, T. et al. Neodymium in the oceans: a global database, a regional comparison and implications for palaeoceanographic research. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 374, 20150293 (2016).

Curry, W. B. & Oppo, D. W. Glacial water mass geometry and the distribution of δ13C of ΣCO2 in the western Atlantic Ocean. Paleoceanography 20, doi: 10.1029/2004PA001021 (2005).

Keigwin, L. D. & Jones, G. A. Western North-Atlantic evidence for millennial-scale changes in ocean circulation and climate. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 99, 12397–12410 (1994).

Poirier, R. K. & Billups, K. The intensification of northern component deepwater formation during the mid‐Pleistocene climate transition. Paleoceanography 29, 1046–1061 (2014).

Liu, Z. et al. Transient simulation of last deglaciation with a new mechanism for bolling-allerod warming. Science 325, 310–314 (2009).

Knorr, G. & Lohmann, G. Rapid transitions in the Atlantic thermohaline circulation triggered by global warming and meltwater during the last deglaciation. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 8, doi: 10.1029/2007GC001604 (2007).

Carlson, A. E. Why there was not a Younger Dryas-like event during the Penultimate Deglaciation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 882–887 (2008).

Galaasen, E. V. et al. Rapid reductions in North Atlantic Deep Water during the peak of the last interglacial period. Science 343, 1129–1132 (2014).

Howe, J. N., Piotrowski, A. M. & Rennie, V. C. Abyssal origin for the early Holocene pulse of unradiogenic neodymium isotopes in Atlantic seawater. Geology 44, 831–834 (2016).

Gong, X., Knorr, G., Lohmann, G. & Zhang, X. Dependence of abrupt Atlantic meridional ocean circulation changes on climate background states. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 3698–3704 (2013).

Hayes, C. T. et al. A stagnation event in the deep South Atlantic during the last interglacial period. Science 346, 1514–1517 (2014).

McCave, I. N. & Hall, I. R. Size sorting in marine muds: processes, pitfalls, and prospects for paleoflow-speed proxies. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 7, doi: 10.1029/2006GC001284 (2006).

Barker, S. et al. Icebergs not the trigger for North Atlantic cold events. Nature 520, 333–336 (2015).

Rasmussen, T. L., Thomsen, E., Kuijpers, A. & Wastegård, S. Late warming and early cooling of the sea surface in the Nordic seas during MIS 5e (Eemian Interglacial). Quat. Sci. Rev. 22, 809–821 (2003).

Van Nieuwenhove, N. et al. Evidence for delayed poleward expansion of North Atlantic surface waters during the last interglacial (MIS 5e). Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 934–946 (2011).

Broecker, W. S. Paleocean circulation during the last deglaciation: a bipolar seesaw? Paleoceanography 13, 119–121 (1998).

Adkins, J. F., Boyle, E. A., Keigwin, L. & Cortijo, E. Variability of the North Atlantic thermohaline circulation during the last interglacial period. Nature 390, 154–156 (1997).

LeGrande, A. N. & Schmidt, G. A. Global gridded data set of the oxygen isotopic composition in seawater. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, doi: 10.1029/2006GL026011 (2006).

Marchitto, T. et al. Improved oxygen isotope temperature calibrations for cosmopolitan benthic foraminifera. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 130, 1–11 (2014).

Adkins, J. F., McIntyre, K. & Schrag, D. P. The salinity, temperature, and δ18O of the glacial deep ocean. Science 298, 1769–1773 (2002).

Wunsch, C. & Heimbach, P. How long to oceanic tracer and proxy equilibrium? Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 637–651 (2008).

Backhaus, J. O., Fohrmann, H., Kämpf, J. & Rubino, A. Formation and export of water masses produced in Arctic shelf polynyas-Process studies of oceanic convection. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 54, 366–382 (1997).

Rysgaard, S., Glud, R. N., Sejr, M., Bendtsen, J. & Christensen, P. Inorganic carbon transport during sea ice growth and decay: a carbon pump in polar seas. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 112, doi:10.1029/2006JC003572 (2007).

Chen, T. et al. Synchronous centennial abrupt events in the ocean and atmosphere during the last deglaciation. Science 349, 1537–1541 (2015).

Ahn, J., Brook, E. J., Schmittner, A. & Kreutz, K. Abrupt change in atmospheric CO2 during the last ice age. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, doi: 10.1029/2012GL053018 (2012).

Thornalley, D. J. R., Barker, S., Becker, J., Knorr, G. & Hall, I. R. Abrupt changes in deep Atlantic circulation during the transition to full glacial conditions. Paleoceanography 28, 253–262 (2013).

Ahn, J. & Brook, E. J. Atmospheric CO2 and climate on millennial time scales during the last glacial period. Science 322, 83–85 (2008).

Anderson, R. F. et al. Wind-driven upwelling in the Southern Ocean and the deglacial rise in atmospheric CO2 . Science 323, 1443–1448 (2009).

Skinner, L. C., Fallon, S., Waelbroeck, C., Michel, E. & Barker, S. Ventilation of the deep Southern Ocean and deglacial CO2 rise. Science 328, 1147–1151 (2010).

Marinov, I. et al. Impact of oceanic circulation on biological carbon storage in the ocean and atmospheric pCO2 . Global Biogeochem. Cycles 22, doi: 10.1029/2007JC004598 (2008).

Köhler, P., Knorr, G. & Bard, E. Permafrost thawing as a possible source of abrupt carbon release at the onset of the Bølling/Allerød. Nat. Commun. 5, doi: 10.1038/ncomms6520 (2014).

Barker, S. & Knorr, G. A paleo-perspective on the AMOC as a tipping element. PAGES Mag. 24, 14–15 (2016).

Broecker, W. S. et al. Evidence for a reduction in the carbonate ion content of the deep sea during the course of the Holocene. Paleoceanography 14, 744–752 (1999).

Le, J. & Shackleton, N. J. Carbonate dissolution fluctuations in the western Equatorial Pacific during the late Quaternary. Paleoceanography 7, 21–42 (1992).

Martin, E. E. et al. Extraction of Nd isotopes from bulk deep sea sediments for paleoceanographic studies on Cenozoic time scales. Chem. Geol. 269, 414–431 (2010).

Pin, C. & Zalduegui, J. S. Sequential separation of light rare-earth elements, thorium and uranium by miniaturized extraction chromatography: application to isotopic analyses of silicate rocks. Anal. Chim. Acta 339, 79–89 (1997).

Crocket, K. C., Lambelet, M., van de Flierdt, T., Rehkämper, M. & Robinson, L. F. Measurement of fossil deep-sea coral Nd isotopic compositions and concentrations by TIMS as NdO+, with evaluation of cleaning protocols. Chem. Geol. 374, 128–140 (2014).

Tanaka, T. et al. JNdi-1: a neodymium isotopic reference in consistency with LaJolla neodymium. Chem. Geol. 168, 279–281 (2000).

Weis, D. et al. High‐precision isotopic characterization of USGS reference materials by TIMS and MC‐ICP‐MS. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 7, doi: 10.1029/2006GC001283 (2006).

Grutzner, J. et al. Astronomical age models for Pleistocene drift sediments from the western North Atlantic (ODP Sites 1055-1063). Mar. Geol. 189, 5–23 (2002).

Channell, J., Hodell, D. & Curtis, J. ODP Site 1063 (Bermuda Rise) revisited: oxygen isotopes, excursions and paleointensity in the Brunhes Chron. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 13, doi:10.1029/2011GC003897 (2012).

Keigwin, L. D. & Boyle, E. A. Surface and deep ocean variability in the northern Sargasso Sea during marine isotope stage 3. Paleoceanography 14, 164–170 (1999).

Loulergue, L. et al. Orbital and millennial-scale features of atmospheric CH4 over the past 800,000 years. Nature 453, 383–386 (2008).

Baumgartner, M. et al. NGRIP CH4 concentration from 120 to 10 kyr before present and its relation to a δ15N temperature reconstruction from the same ice core. Clim. Past 10, 903–920 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank Katharina Kreissig, Sian Lordsmith, Stephen Conn and Lindsey Owen for laboratory assistance, Torben Struve for help with Nd isotope analyses, and David Thornalley, Sophie Nuber and Gregor Knorr for discussions. The SS data from ODP 983 were produced by Fiona Piggott (Cardiff University) as part of her MESci undergraduate thesis project in 2012/13. This research used samples provided by the Integrated Ocean Drilling Programme (IODP). We acknowledge support from UK NERC (grants NE/J008133/1, NE/J021636/1, and NE/L006405/1) and a President’s Research Scholarship at Cardiff University (ED).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.L.D. performed laboratory work on material from ODP 1063 with assistance from those mentioned in the acknowledgements. All authors helped design the project, interpret datasets and write the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Data 1

Excel file containing all results from this study and published data from ODP sites 983 and 1063 as used in Figures 2 and 3. (XLSX 267 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Deaney, E., Barker, S. & van de Flierdt, T. Timing and nature of AMOC recovery across Termination 2 and magnitude of deglacial CO2 change. Nat Commun 8, 14595 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14595

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14595

This article is cited by

-

Millennial scale feedbacks determine the shape and rapidity of glacial termination

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Abrupt climate changes in the last two deglaciations simulated with different Northern ice sheet discharge and insolation

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Oceanic forcing of penultimate deglacial and last interglacial sea-level rise

Nature (2020)

-

Global ocean heat content in the Last Interglacial

Nature Geoscience (2020)

-

Role of Asian summer monsoon subsystems in the inter-hemispheric progression of deglaciation

Nature Geoscience (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.