Abstract

Magnetic skyrmions are particle-like topological excitations recently discovered in chiral magnets. Their small size, topological protection and the ease with which they can be manipulated by electric currents generated much interest in using skyrmions for information storage and processing. Recently, it was suggested that skyrmions with additional degrees of freedom can exist in magnetically frustrated materials. Here, we show that dynamics of skyrmions and antiskyrmions in nanostripes of frustrated magnets is strongly affected by complex spin states formed at the stripe edges. These states create multiple edge channels which guide the skyrmion motion. Non-trivial topology of edge states gives rise to complex current-induced dynamics, such as emission of skyrmion–antiskyrmion pairs. The edge-state topology can be controlled with an electric current through the exchange of skyrmions and antiskyrmions between the edges of a magnetic nanostructure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chiral magnets, that is, magnets with a non-centrosymmetric crystal lattice, show a variety of non-collinear magnetic states stabilized by the relativistic Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya (DM) interaction. The recent discovery of skyrmions in chiral magnets1,2 led to many theoretical and experimental studies of unusual physical properties of these topological excitations3. Low critical currents required to set skyrmions into motion4,5 opened a new active field of research in memory and logic devices, in which information is carried by skyrmions6,7,8,9,10,11.

The DM interaction imprints the chirality of crystal lattice into the chirality of magnetic orders: the direction of spin rotation in spirals and skyrmions is determined by the lattice. Chiral magnetic states can also originate from competing ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic exchange interactions between spins in Mott insulators. It was recently shown that frustrated magnets form a new class of materials that can host skyrmion crystals and isolated skyrmions12,13. In contrast to DM interactions, exchange interactions are insensitive to the direction of spin rotation in non-collinear magnetic states, which gives skyrmions two additional degrees-of-freedom—vorticity and helicity. In frustrated magnets, skyrmions coexist with antiskyrmions and carry a reversible electric dipole moment13,14. Magnetic frustration is not limited to Mott insulators: RKKY interactions15, competing double exchange and superexchange interactions16, double exchange in charge-transfer systems17 and fluxes of effective magnetic fields18,19,20 can stabilize non-collinear and even non-coplanar magnetic states in itinerant magnets.

Here, we explore the current-induced dynamics of skyrmions and antiskyrmions in nanostripes of frustrated magnets and show that it is strongly affected by the periodically modulated spin structures formed at the stripe edges. These edge states are topological and have a highly nonlinear dynamics of their own: under an applied electric current they emit and absorb skyrmions and antiskyrmions. These processes, governed by a topological conservation law, allow for the electric control of edge-state topology.

Results

Edge states and edge channels in frustrated magnets

The nontrivial skyrmion topology gives rise to a high energy barrier that prevents the decay of skyrmions into magnons. However, near the boundaries of a magnet this barrier can be significantly lower or may not exist at all. Therefore, the practical use of skyrmions crucially depends on their repulsion from edges of magnetic nanostructures. In chiral magnets such a repulsion is naturally provided by the bulk DM interaction, which tilts the magnetization vector away from the magnetic field direction at the edges of a magnet, giving rise to the so-called edge states21,22,23,24.

Competing spin interactions in frustrated magnets do not necessarily induce similar spin tilts. However, exchange interactions and magnetic anisotropies at surfaces or interfaces of magnetic materials can be significantly different from those in bulk, because of a lower symmetry of magnetic ions at the edges25,26,27. We have found that a strong surface anisotropy gives rise to edge states in frustrated magnets with a variety of complex structures, which confine skyrmions to a nanostripe.

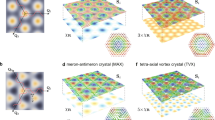

We studied minimal-energy states in a stripe of a frustrated magnet (Fig. 1a)13,

(a) Schematic of current-driven motion of skyrmions with various vorticities and helicities confined by the edge states in the stripe of width Ly. The electric current runs along the x axis. The magnetic field antiparallel to the z axis induces a saturated ferromagnetic state inside the stripe, in which skyrmions are stable topological defects. The colour of arrows from red (mz=−1) to blue (mz=+1) indicates the alignment of the magnetization vector with respect to the magnetic field. The edge states are induced by changing the type of magnetic anisotropy (from easy axis to easy plane) in one or two rows of spins near the edges of the stripe. (b) Three types of edge states: (I) the state with parallel in-plane spin components, (II) the evanescent conical spiral state and (III) the state with fan-like oscillations of in-plane spins. Arrows show the in-plane components of magnetization; colour indicates the scalar chirality of spin triangles g=(m1·m2 × m3) proportional to the topological charge density. (c) Oscillations of the magnetization components, mz and  , along the y coordinate (dotted red line and solid black line, respectively) in type I edge state near the lower edge of the nanostripe. Distances are measured in units of the lattice constant a. The width of the stripe Ly is large enough to avoid an overlap between the upper and lower edge states.

, along the y coordinate (dotted red line and solid black line, respectively) in type I edge state near the lower edge of the nanostripe. Distances are measured in units of the lattice constant a. The width of the stripe Ly is large enough to avoid an overlap between the upper and lower edge states.

where mi is the unit vector in the direction of the magnetization at the site i of a triangular lattice. The first and the second terms in the energy describe the competing ferromagnetic nearest-neighbour and antiferromagnetic next-nearest-neighbour interactions (J1, J2>0), h is the magnetic field applied in the z direction normal to the stripe, K>0 is the bulk easy axis magnetic anisotropy and  <0 is the easy plane anisotropy added near the edges. The rich phase diagram of this model counts 8 different phases including the skyrmion crystal state13. Important for our present study is a large region of the field-induced collinear ferromagnetic state, where isolated skyrmions are stable. We use the set of bulk model parameters, J2=0.5, h=0.4, K=0.2 (in units of J1=1), for which spins inside the stripe are normal to the stripe plane. The easy plane edge anisotropy favors a conical spiral state near the edges, which gives rise to edge states with complex spin structures.

<0 is the easy plane anisotropy added near the edges. The rich phase diagram of this model counts 8 different phases including the skyrmion crystal state13. Important for our present study is a large region of the field-induced collinear ferromagnetic state, where isolated skyrmions are stable. We use the set of bulk model parameters, J2=0.5, h=0.4, K=0.2 (in units of J1=1), for which spins inside the stripe are normal to the stripe plane. The easy plane edge anisotropy favors a conical spiral state near the edges, which gives rise to edge states with complex spin structures.

Figure 1b shows three types of evanescent edge states induced by the easy plane surface anisotropy in one or more rows at the edges of the magnetic stripe. The type I edge state with collinear in-plane spin components is induced by K′≤−0.434 in the first row; K′=0 in the first row and K′≤−0.808 in the second row induces type II state—the evanescent conical spiral state with the wave vector along the boundary (x direction) and the in-plane magnetization vector rotating around the z axis. K′=−0.406 in the first row and K′=−0.203 in the second row give rise to type III state, in which the in-plane magnetization vector shows fan-like oscillations around a fixed direction in the xy plane. Importantly, in all edge states the in-plane magnetization oscillates with the decaying amplitude along the y axis normal to the edge (Fig. 1c).

These oscillations are a characteristic property of frustrated magnets and the three types of edge states are generic. The origin of the oscillations can be understood by considering asymptotic of the in-plane magnetization vector, m⊥(x)∝eiq·x, deep inside the magnetic stripe. In the continuum limit,  ,

,

where the first two terms originate from the expansion of the exchange energy of a frustrated magnet in powers of q (a= (3J2−J1)>0, b=

(3J2−J1)>0, b= (9J2−J1)>0). This bi-quadratic equation with real coefficients has four solutions: ±q=±(q′+iq″) and ±q*=±(q′−iq″). In the situation when modulated states are suppressed in the bulk, all four wave vectors have a nonzero imaginary part q″. They can be grouped into two pairs according to the sign of q″: (+q′+iq″,−q′+iq″) and (+q′−iq″,−q′ −iq″). One pair describes m⊥ with an amplitude decreasing away from the upper edge and another pair describes the evanescent state near the lower edge. The real parts of the two wave vectors in each pair have opposite signs. The interference between the modulations with positive and negative q′ leads to spin oscillations.

(9J2−J1)>0). This bi-quadratic equation with real coefficients has four solutions: ±q=±(q′+iq″) and ±q*=±(q′−iq″). In the situation when modulated states are suppressed in the bulk, all four wave vectors have a nonzero imaginary part q″. They can be grouped into two pairs according to the sign of q″: (+q′+iq″,−q′+iq″) and (+q′−iq″,−q′ −iq″). One pair describes m⊥ with an amplitude decreasing away from the upper edge and another pair describes the evanescent state near the lower edge. The real parts of the two wave vectors in each pair have opposite signs. The interference between the modulations with positive and negative q′ leads to spin oscillations.

In fact, any magnetic defect in frustrated magnets, such as skyrmion or domain wall, gives rise to similar decaying spin oscillations. They lead to sign changes of the skyrmion-skyrmion interaction potential as a function of distance between two skyrmions13. Similarly, the interaction energy of skyrmion with an edge state, U(y), obtained by setting mz(x, y)=−1 and minimizing the energy (1) with respect to spins at all other sites, oscillates with y (Fig. 2a). This leads to a sequence of edge channels centred around minima of U(y) (Fig. 2b), which run continuously along the boundaries of a nanostructure and guide the motion of skyrmions.

(a) The skyrmion potential energy U (measured in units of J1) versus the distance y between the skyrmion centre and the edge of the stripe for type I (blue line with circular markers) and type II (red line with square markers) edge states. U(y) was calculated by imposing the constraint, mz=−1, at the skyrmion centre and minimizing the energy with respect to spins at all other sites. (b) The potential energy landscape for skyrmion interacting with type III state. The local minima of U(y) give rise to a sequence of edge channels separated by the potential barriers, which guide the current-induced motion of skyrmions. The edge channels are numbered starting from the edge (that is, the first channel corresponds to the global minimum of U(y)) and are indicated by red and blue arrows. (c) The skyrmion potential energy U(y, χ) calculated by constraining the skyrmion centre, mz(x, y)=−1, and the helicity, χ, of six neighbouring spins (see text for details) for type I edge state. The corresponding 2D plot with a colour bar is shown in Fig. 4a.

In equation (2) q2= +

+ . For periodic boundary conditions along the x direction, qx=

. For periodic boundary conditions along the x direction, qx= , where Lx is the length of the stripe and N is an integer number. Thus equation (2) gives qy for a given N. For type I state N=0, for type II state N=5 shown in Fig. 1b and type III state is a superposition of type I and type II states.

, where Lx is the length of the stripe and N is an integer number. Thus equation (2) gives qy for a given N. For type I state N=0, for type II state N=5 shown in Fig. 1b and type III state is a superposition of type I and type II states.

Edge channels are closely related to helicity reversals around skyrmions in achiral systems13,28, which becomes clear if we calculate the potential U(y, χ) (Fig. 2c) for skyrmion near type I edge state in the following way. In addition to constraining the skyrmion position by mz(x, y)=−1, we constrain its helicity, χ, (ref. 3) by imposing the in-plane spin directions at six sites neighbouring to the skyrmion centre. We also constrain the in-plane spin directions at the edge by  (edge)=0, where

(edge)=0, where  is the azimuthal angle describing the direction of m. Edge states, like skyrmions, have a helicity and the potential U(y, χ) depends on the relative helicity of skyrmion and edge state. Figure 2c shows that the helicity angle in the edge channels, corresponding to minima of U(y, χ), alternates between 0 and π.

is the azimuthal angle describing the direction of m. Edge states, like skyrmions, have a helicity and the potential U(y, χ) depends on the relative helicity of skyrmion and edge state. Figure 2c shows that the helicity angle in the edge channels, corresponding to minima of U(y, χ), alternates between 0 and π.

Motion of skyrmions through the edge channels

In the continuum limit, in which the period of modulated states and the skyrmion diameter are much larger than the lattice constant, the spin model (1) can be used to describe itinerant frustrated magnets. We study the current-induced dynamics of skyrmions and antiskyrmions in the stripe of a frustrated magnet with edge states by solving Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert equation (see ‘Methods’) with the electric current jx running along the stripe (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Movies 1 and 2). In contrast to chiral magnets, the skyrmion vorticity v in frustrated magnets can have either sign, v=±1 (refs 3, 12, 13), so that for a given direction of the magnetic field, the skyrmion topological charge, Q=−sign(h)v, also can have either sign. Assuming h<0, we call the magnetic defects with positive vorticity, v=Q=+1, skyrmions, while those with v=Q=−1 are called antiskyrmions.

Figure 3a shows the time dependence of the y coordinate of skyrmion, initially placed into the channel 3, for several values of the electric current (Supplementary Movie 1). A relatively low current, jx=0.025j0, moves skyrmion along the channel, where the unit of current j0 is defined in the ‘Methods’, equation (9). A larger current, jx=0.05j0, forces skyrmion to jump into the channel 2, and jx=0.1j0, eventually brings skyrmion into the channel 1 (the one closest to the edge). Figure 3b shows that the x component of the skyrmion velocity Vx varies, when the skyrmion moves across channels, and approaches a constant value, when it moves in a channel. Thus the channel, in which skyrmion moves, can be selected by the electric current.

(a) Time dependence of the y coordinate of the skyrmion centre for β=0.8α, α and β being the Gilbert damping constant and the non-adiabatic spin-torque strength, respectively (Supplementary Movie 1). Skyrmion is initially located in the third channel of type III edge state. For jx=0.025j0 (equation (9)) skyrmion moves in the third channel (green dash-dotted line); for jx=0.05j0, it jumps into the second channel (dashed red line) and for jx=0.1j0 it eventually ends up in the first channel (black solid line). The time t is measured in units of  . (b) Time dependence of the skyrmion drift velocity, Vx, measured in units of

. (b) Time dependence of the skyrmion drift velocity, Vx, measured in units of  for the same parameters as in (a). For jx=0.1j0, skyrmion changes channels twice, which gives rise to two humps in Vx(t). In the steady state Vx∝jx. (c) Time dependence of Vx for jx=0.1j0 and several values of β (Supplementary Movie 2). For β=α (green dashed line), skyrmion always moves in the third channel; for β=0.5α (blue dotted line), skyrmion jumps into the second channel, in which it moves together with the edge state; for β=0 (solid red line), skyrmion ends up in the first channel and comes to a halt. For the steady state motion along a channel, Vx∝β.

for the same parameters as in (a). For jx=0.1j0, skyrmion changes channels twice, which gives rise to two humps in Vx(t). In the steady state Vx∝jx. (c) Time dependence of Vx for jx=0.1j0 and several values of β (Supplementary Movie 2). For β=α (green dashed line), skyrmion always moves in the third channel; for β=0.5α (blue dotted line), skyrmion jumps into the second channel, in which it moves together with the edge state; for β=0 (solid red line), skyrmion ends up in the first channel and comes to a halt. For the steady state motion along a channel, Vx∝β.

The driving force for the channel switching is the skyrmion Hall effect, that is, the skyrmion motion with a velocity Vy in the direction transverse to the applied current29,30. The skyrmions and antiskyrmions are deflected towards opposite edges of the magnetic stripe, which eventually drives them into the edge channels where both Vx and Vy are strongly affected by the oscillating edge-state potential, U(y, χ).

The skyrmion motion through the system of edge channels is qualitatively described by Thiele equations30:

which have to be solved together with the equation for the relative helicity angle (Supplementary Note 1),

Here  ,

,  ,

,  , M is the ‘helicity mass’, α is the Gilbert damping constant and β describes the non-adiabatic spin-torque.

, M is the ‘helicity mass’, α is the Gilbert damping constant and β describes the non-adiabatic spin-torque.

For an unconstrained skyrmion motion away from the edges (U=0) and equation (3) gives

for α, β<<1. On the other hand, for a skyrmion moving along the channel (Vy=0),

and  .

.

The skyrmion Hall effect pushes skyrmion towards the edge and when it moves from one channel into another the helicity angle varies by ±π (Fig. 4a,b), which explains the rotation of spins in the skyrmion that occurs during the channel switching (Supplementary Movie 2). The solution of equations (3) and (4) reproduces the jumps in the helicity angle (dotted line in Fig. 4a) and is in reasonable agreement with the skyrmion trajectory extracted from the numerical solution of the Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert equation (solid line in Fig. 4a). The only fitting parameter of the simplified description of skyrmion dynamics is the helicity mass  .

.

(a) y dependence of the relative helicity, χ, obtained from the numerical solution of the Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert equation (solid white line) and from the solution of Thiele equations (3) and (4) (dotted line). The colour plot shows the potential U(y, χ) (Fig. 2). (b) Time dependence of the relative helicity of the skyrmion and edge state for jx=0.1j0 (equation (9)) and β=0.5α. The time t is measured in units of  .

.

Equation (6) also applies to type II and type III edge states that are inhomogeneous along the x axis and, therefore, move along the boundary when an electric current is applied. When skyrmion is captured by such an edge state, they move with the same speed. This speed is proportional to β and the motion stops for β=0 (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Movie 2).

The simultaneous presense of skyrmions and antiskyrmions in frustrated magnets can be very useful for implementation of logical operations. However, since skyrmions and antiskyrmions have the same energy, they can form random mixtures (Fig. 5a). The skyrmion Hall effect can be employed to separate them: since the sign of the transverse velocity depends on the sign of topological charge (equation (5)), skyrmions and antiskyrmions under an applied current move towards opposite edges. Supplementary Movie 3 shows how the skyrmion Hall effect and a notch at one of the edges help to filter out antiskyrmions. The final state with skyrmions separated from antiskyrmions is shown in Fig. 5b.

(a) The initial state of two skyrmions (their positive topological charge density is indicated by yellow colour) and four antiskyrmions (dark green colour indicating negative topological charge density). (b) The final configuration after the electric current jx/j0=0.02 (equation (9)) was applied for the time t=1.8 × 104 (Supplementary Movie 3). The motion of skyrmions is hindered by a notch. Skyrmions are deflected towards the lower-edge channels of the nanotrack.

(Supplementary Movie 3). The motion of skyrmions is hindered by a notch. Skyrmions are deflected towards the lower-edge channels of the nanotrack.

Instability of edge states

Above a critical electric current edge states become unstable against emission of skyrmion–antiskyrmion pairs. Figure 6 and Supplementary Movie 4 show complex dynamics of type II edge states under an applied current jx=0.02j0. These spiral edge states with in-plane spins at the edge are characterized by the winding number,  , where

, where  is the angle describing the spin orientation and the +/− sign is for the upper/lower edge. For periodic boundary conditions along the x axis, N is an integer number. In the initial state (Fig. 6a) Nu=+1 at the upper edge and Nd=−3 at the lower edge. Under the applied current the upper-edge state becomes unstable and emits two skyrmion–antiskyrmion pairs (Fig. 6b,c). The skyrmion Hall effect pushes skyrmions towards the lower edge, while antiskyrmions return to the upper edge (Fig. 6d,e). After the skyrmions and antiskyrmions have vanished at the corresponding edges, the winding numbers of the edge states become Nu=Nd=−1 (Fig. 6f). Then the lower edge state becomes unstable and emits two skyrmion–antiskyrmion pairs (Fig. 6g), which separate into two skyrmions that return to the lower edge and two skyrmions that move towards the upper edge (Fig. 6h). In the final state (Fig. 6i) the winding numbers of the edge states are Nu=−3 and Nd=+1, that is, in the end of these transformations the upper and lower edge states exchanged their winding numbers. The final state is stable.

is the angle describing the spin orientation and the +/− sign is for the upper/lower edge. For periodic boundary conditions along the x axis, N is an integer number. In the initial state (Fig. 6a) Nu=+1 at the upper edge and Nd=−3 at the lower edge. Under the applied current the upper-edge state becomes unstable and emits two skyrmion–antiskyrmion pairs (Fig. 6b,c). The skyrmion Hall effect pushes skyrmions towards the lower edge, while antiskyrmions return to the upper edge (Fig. 6d,e). After the skyrmions and antiskyrmions have vanished at the corresponding edges, the winding numbers of the edge states become Nu=Nd=−1 (Fig. 6f). Then the lower edge state becomes unstable and emits two skyrmion–antiskyrmion pairs (Fig. 6g), which separate into two skyrmions that return to the lower edge and two skyrmions that move towards the upper edge (Fig. 6h). In the final state (Fig. 6i) the winding numbers of the edge states are Nu=−3 and Nd=+1, that is, in the end of these transformations the upper and lower edge states exchanged their winding numbers. The final state is stable.

(a) The initial state with the winding numbers Nu=+1 and Nd=−3. (b–d) Emission of two skyrmion–antiskyrmion pairs from the upper edge. Antiskyrmions are driven by the skyrmion Hall effect towards the upper edge. When they are absorbed the winding number of the upper edge state changes to Nu=−1. (e) Two skyrmions are absorbed by the lower edge state and change its winding number to Nd=−1. (f,g) Emission of two skyrmion–antiskyrmion pairs from the lower edge. Two skyrmions return to the lower edge and change its winding number to Nd=+1. (h) Two antiskyrmions pass through the upper edge, after which Nu=−3. (i) The final state with the interchanged winding numbers is stable. This simulation was performed for jx=0.02j0 (equation (9)), β=0, J2=0.36J1 and h=0.05J1. The time t is measured in units of  .

.

These metamorphoses can be understood, if we notice that the type II edge state with in-plane spins at the edge has topological charge,  , where

, where  is the z-component of the unit magnetization vector m at the edge,

is the z-component of the unit magnetization vector m at the edge,  is the bulk value of mz and N is the winding number of the edge state. For

is the bulk value of mz and N is the winding number of the edge state. For  =0 and

=0 and  =−1, the topological charge, Qedge=

=−1, the topological charge, Qedge= N, is integer or half-integer. More generally, edge states carry a fractional topological charge. The reason for the instability of the upper-edge state, which initially had Qu=+1/2, is the skyrmion Hall effect that, for jx>0, pushes this state downwards. Similarly, the lower-edge state with a negative topological number is pushed upwards, which leads to its instability (Fig. 6f,g). In the stable final state (Fig. 6i) the upper-edge state has negative topological charge, Qu=−3/2, and lower-edge state has positive topological charge, Qd=+1/2. These states can be made unstable by reversing the direction of the electric current.

N, is integer or half-integer. More generally, edge states carry a fractional topological charge. The reason for the instability of the upper-edge state, which initially had Qu=+1/2, is the skyrmion Hall effect that, for jx>0, pushes this state downwards. Similarly, the lower-edge state with a negative topological number is pushed upwards, which leads to its instability (Fig. 6f,g). In the stable final state (Fig. 6i) the upper-edge state has negative topological charge, Qu=−3/2, and lower-edge state has positive topological charge, Qd=+1/2. These states can be made unstable by reversing the direction of the electric current.

Remarkably, when skyrmion or antiskyrmion vanishes at an edge, the winding number of the edge state changes by ±1, which suggests that such processes are governed by a conservation law of topological nature. The total topological charge of the stripe equal the sum of topological charges of skyrmions, antiskyrmions and the two edge states, is not conserved. For example, when a skyrmion with Q=+1 passes through the lower edge, the topological charge of the edge state increases by +1/2. What is conserved, is the total vorticity equal the sum of vorticities of skyrmions and antiskyrmions inside the stripe and the winding numbers of the edge states:

Here, Ns is the number of skyrmions with vorticity +1 and Na is the number of antiskyrmions with vorticity −1. One can check that vtotal is invariant under all transmutations shown in Fig. 6, including the emission of skyrmion–antiskyrmion pairs. When skyrmion is absorbed by an edge, the ring of in-plane spins winding around the skyrmion centre is cut, stretched into a straight segment and becomes a part of the edge state, which explains the conservation of vorticity.

The current-induced instability of edge states in frustrated magnets that leads to emission of skyrmion–antiskyrmion pairs, is analogous to the magnetic-field-induced instability of chiral magnets, which generates chains of skyrmions parallel to the edges31,32,33. The novel aspect of our study is the crucial role of the edge state topology and the skyrmion Hall effect for the emergence of the instability. The skyrmion Hall effect is likely involved in the nucleation of skyrmions at boundaries with sharp corners30. Equation (7) describing the conservation of the total vorticity in the skyrmion/antiskyrmion absorption by the edge states is similar to the winding number conservation that governs the dynamics of domain walls and half-integer vortices in ferromagnetic nanostripes34,35. In those systems, however, magnetization is confined to the stripe plane, whereas in our case the magnetization inside the stripe is vertical.

Discussion

In conclusion, we showed that the states formed at the edges of frustrated magnets give rise to interesting physics, which can be useful in more than one way. The multiple edge channels continuously running along the boundaries of magnetic nanostructures and guiding the motion of skyrmions can be employed for magnetic patterning of nanodevices. Skyrmions, which fit perfectly into these edge channels, can be directed by pulsed currents along different paths. The simultaneous presence of skyrmions and antiskyrmions, which under an applied current move towards opposite edges, opens additional possibilities to do logical operations with these topological objects. Our results suggest that information can be stored in winding numbers of edge states and manipulated by electric currents through the exchange of skyrmions and antiskyrmions between the edges. These results open new avenues for design of magnetic devices.

Methods

Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert equation

The current-driven dynamics of spin textures was simulated using Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert equation for the unit vector m in the direction of magnetization,

which was solved using fourth-order Runge–Kutta method. Here, Heff is a local effective magnetic field, which at the site i is given by  , α=0.01 is the Gilbert damping constant and β is the dimensionless strength of the non-adiabatic torque36,37. All physical quantities in our calculations are dimensionless: we measure time t in units of

, α=0.01 is the Gilbert damping constant and β is the dimensionless strength of the non-adiabatic torque36,37. All physical quantities in our calculations are dimensionless: we measure time t in units of  , where J1 is the nearest-neighbor exchange constant, energy E in units of J1, distances in units of the triangular lattice constant a, current density in units of

, where J1 is the nearest-neighbor exchange constant, energy E in units of J1, distances in units of the triangular lattice constant a, current density in units of

where e is the absolute value of the electron charge, p is the spin polarization of the electric current and v0 is the unit cell volume (we assume that the unit cell contains one spin S=1). Spin configurations were first relaxed at zero current. When the convergence was reached, the electric current was applied along the x direction.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Leonov, A. O. et al. Edge states and skyrmion dynamics in nanostripes of frustrated magnets. Nat. Commun. 8, 14394 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14394 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Mühlbauer, S. et al. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science 323, 915–919 (2009).

Yu, X. Z. et al. Real-space observation of a two-dimensional skyrmion crystal. Nature 465, 901–904 (2010).

Nagaosa, N. & Tokura, Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 899–911 (2013).

Jonietz, F. et al. Spin transfer torques in MnSi at ultralow current densities. Science 330, 1648–1651 (2010).

Yu, X. Z. et al. Skyrmion flow near room temperature in an ultralow current density. Nat. Commun. 3, 988 (2012).

Fert, A., Cros, V. & Sampaio, J. Skyrmions on the track. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 152–156 (2013).

Sampaio, J., Cros, V., Rohart, S., Thiaville, A. & Fert, A. Nucleation, stability and current-induced motion of isolated magnetic skyrmions in nanostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 839–844 (2013).

Tomasello, E. M. R., Zivieri, R., Torres, L., Carpentieri, M. & Finocchio, G. A strategy for the design of skyrmion racetrack memories. Sci. Rep. 4, 6784 (2014).

Jiang, W. et al. Blowing magnetic skyrmion bubbles. Science 349, 283–286 (2015).

Moreau-Luchaire, C. et al. Additive interfacial chiral interaction in multilayers for stabilization of small individual skyrmions at room temperature. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 444–448 (2016).

Woo, S. et al. Observation of room-temperature magnetic skyrmions and their current-driven dynamics in ultrathin metallic ferromagnets. Nat. Mater. 15, 501–506 (2016).

Okubo, T., Chung, S. & Kawamura, H. Multiple-q states and the skyrmion lattice of the triangular-lattice Heisenberg antiferromagnet under magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 017206 (2012).

Leonov, A. O. & Mostovoy, M. Multiply periodic states and isolated skyrmions in an anisotropic frustrated magnet. Nat. Commun. 6, 8275 (2015).

Hayami, S., Lin, S.-Z. & Batista, C. D. Bubble and skyrmion crystals in frustrated magnets with easy-axis anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 93, 184413 (2016).

Jensen, J. & Macintosh, A. R. Rare Earth Magnetism. Structures and Excitations 68, Clarendon Press (1991).

de Gennes, P.-G. Effects of double exchange in magnetic crystals. Phys. Rev. 118, 141–154 (1960).

Mostovoy, M. Helicoidal ordering in iron perovskites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 137205 (2005).

Martin, I. & Batista, C. D. Itinerant electron-driven chiral magnetic ordering and spontaneous quantum Hall Effect in triangular lattice models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 156402 (2008).

Akagi, Y. & Motome, Y. Spin chirality ordering and anomalous hall effect in the ferromagnetic Kondo lattice model on a triangular lattice. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 79, 083711 (2010).

Kumar, S. & van den Brink, J. Frustration-induced insulating chiral spin state in itinerant triangular-lattice magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 216405 (2010).

Wilson, M. N. et al. Discrete helicoidal states in chiral magnetic thin films. Phys. Rev. B 88, 214420 (2013).

Rohart, S. & Thiaville, A. Skyrmion confinement in ultrathin film nanostructures in the presence of Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 88, 184422 (2013).

Meynell, S. A., Wilson, M. N., Fritzsche, H., Bogdanov, A. N. & Monchesky, T. L. Surface twist instabilities and skyrmion states in chiral ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 90, 014406 (2014).

Keesman, R. et al. Néel skyrmions in confined geometries and at nonzero temperatures. Phys. Rev. B 92, 134405 (2015).

Gay, J. G. & Richter, R. Spin anisotropy of ferromagnetic films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 2728 (1986).

Bruno, P. & Renard, J.-P. Magnetic surface anisotropy of transition metal ultrathin films. Appl. Phys. A 49, 499–506 (1989).

Johnson, M. T., Bloemen, P. J. H., den Broeder, F. J. A. & de Vries, J. J. Magnetic anisotropy in metallic multilayers. Rep. Prog. Phys. 59, 1409–1458 (1996).

Yu, X. Z. et al. Magnetic stripes and skyrmions with helicity reversals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 8856–8860 (2012).

Zang, J., Mostovoy, M., Han, J. H. & Nagaosa, N. Dynamics of skyrmion crystals in metallic thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 136804 (2011).

Iwasaki, J., Mochizuki, M. & Nagaosa, N. Current-induced skyrmion dynamics in constricted geometries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 742 (2013).

Du, H. et al. Edge-mediated skyrmion chain and its collective dynamics in a confined geometry. Nat. Commun. 6, 8504 (2015).

Garcia-Sanchez, F., Borys, P., Vansteenkiste, A., Kim, J.-V. & Stamps, R. L. Nonreciprocal spin-wave channeling along textures driven by the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 89, 224408 (2014).

Müller, J., Rosch, A. & Garst, M. Edge instabilities and skyrmion creation in magnetic layers. New J. Phys. 18, 06500 (2016).

Tchernyshyov, O. & Chern, G.-W. Fractional vortices and composite domain walls in flat nanomagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 197204 (2005).

Pushp, A. et al. Domain wall trajectory determined by its fractional topological edge defects. Nat. Phys. 9, 505–511 (2013).

Zhang, S. & Li, Z. Roles of nonequilibrium conduction electrons on the magnetization dynamics of ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 127204 (2004).

Iwasaki, J., Mochizuki, M. & Nagaosa, N. Universal current–velocity relation of skyrmion motion in chiral magnets. Nat. Commun. 4, 1463 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank N. Nagaosa for interesting discussions. This study was supported by the FOM Grant 11PR2928.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to all aspects of this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary References. (PDF 40 kb)

Supplementary Movie 1

Simulated current-induced motion of skyrmions in a stripe of a frustrated triangular magnet with type III edge states. The movie frames are taken with the interval  . The simulation was performed for β=0.8α and several values of the current density (see Fig. 3 a,b): jx=0.1j0 (the first part of the Movie), jx=0.05j0 (the second part of the Movie), jx=0.025j0 and (the third part of the Movie). The easy plane anisotropy near the edges is

. The simulation was performed for β=0.8α and several values of the current density (see Fig. 3 a,b): jx=0.1j0 (the first part of the Movie), jx=0.05j0 (the second part of the Movie), jx=0.025j0 and (the third part of the Movie). The easy plane anisotropy near the edges is  . The in-plane components of the magnetization are represented by black arrows. Colour indicates the scalar chirality of spin triangles, g, proportional to the topological charge density. (MOV 29381 kb)

. The in-plane components of the magnetization are represented by black arrows. Colour indicates the scalar chirality of spin triangles, g, proportional to the topological charge density. (MOV 29381 kb)

Supplementary Movie 2

Simulated current-induced motion of skyrmions in a stripe of a frustrated triangular magnet with type III edge states. The movie frames are taken with the interval  . The simulation was performed for the current density jx=0.1j0 and several values of β:β=0.5α (the first part of the Movie), β=0 (the second part of the Movie) (see Fig. 3c). The easy plane anisotropy near the edges is

. The simulation was performed for the current density jx=0.1j0 and several values of β:β=0.5α (the first part of the Movie), β=0 (the second part of the Movie) (see Fig. 3c). The easy plane anisotropy near the edges is  . The in-plane components of the magnetization are represented by black arrows. Color indicates the scalar chirality of spin triangles, g. (MOV 16574 kb)

. The in-plane components of the magnetization are represented by black arrows. Color indicates the scalar chirality of spin triangles, g. (MOV 16574 kb)

Supplementary Movie 3

Topological filtering of skyrmions and antiskyrmions in a nanotrack with a notch (see Fig. 4 and text for details). In the initial state we have a cluster of four antiskyrmions and two skyrmions. In-plane components of the spins are represented by black arrows and colour indicates the scalar chirality of spin triangles, g, proportional to the topological charge density. Periodic boundary conditions are used along the x direction. The numerical simulation was performed for β=0.5alpha, jx=0.02j0 and  . The applied current deflects skyrmions towards the lower boundary of the nanotrack, whereas antiskyrmions are pushed to the upper edge. Eventually, the antiskyrmions stop at the corners of the notch, while their helicity keeps changing in time. Skyrmions, on the contrary, keep moving near the lower edge. Due to the periodic boundary conditions, this movie actually describes the propagation of skyrmions and antiskyrmions through an array of notches. (MOV 11747 kb)

. The applied current deflects skyrmions towards the lower boundary of the nanotrack, whereas antiskyrmions are pushed to the upper edge. Eventually, the antiskyrmions stop at the corners of the notch, while their helicity keeps changing in time. Skyrmions, on the contrary, keep moving near the lower edge. Due to the periodic boundary conditions, this movie actually describes the propagation of skyrmions and antiskyrmions through an array of notches. (MOV 11747 kb)

Supplementary Movie 4

Exchange of winding numbers of upper and lower edge states under the applied current (see Fig. 5 and text for details). In the initial state Nu=+1 and Nd=−3 In the final state it is the other way around. Colour indicates the scalar chirality of spin triangles, g. Periodic boundary conditions are used along the x direction. The numerical simulation was performed for jx=0.02j0, β=0, j2=0.36 and h=0.05. The easy plane anisotropy spreads over the three edge rows and equals  . The instability of the edge states leads to emission of skyrmion-antiskyrmion pairs, first from the upper edge state and then from the lower state. The skyrmion Hall effect pushes skyrmions to the lower edge and antiskyrmions to the upper edge. The vorticity conservation leads to changes in the winding numbers of the edge states, when skyrmions and antiskyrmion pass through the edges. The final state is stable. (MOV 19613 kb)

. The instability of the edge states leads to emission of skyrmion-antiskyrmion pairs, first from the upper edge state and then from the lower state. The skyrmion Hall effect pushes skyrmions to the lower edge and antiskyrmions to the upper edge. The vorticity conservation leads to changes in the winding numbers of the edge states, when skyrmions and antiskyrmion pass through the edges. The final state is stable. (MOV 19613 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Leonov, A., Mostovoy, M. Edge states and skyrmion dynamics in nanostripes of frustrated magnets. Nat Commun 8, 14394 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14394

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14394

This article is cited by

-

Constructing coarse-grained skyrmion potentials from experimental data with Iterative Boltzmann Inversion

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Unveiling the three-dimensional magnetic texture of skyrmion tubes

Nature Nanotechnology (2022)

-

Skyrmion ratchet propagation: utilizing the skyrmion Hall effect in AC racetrack storage devices

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Dipolar-stabilized first and second-order antiskyrmions in ferrimagnetic multilayers

Nature Communications (2021)

-

The optical tweezer of skyrmions

npj Computational Materials (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.