Abstract

Alteration of ultramafic rocks plays a major role in the production of hydrocarbons and organic compounds via abiotic processes on Earth and beyond and contributes to the redistribution of C between solid and fluid reservoirs over geological cycles. Abiotic methanogenesis in ultramafic rocks is well documented at shallow conditions, whereas natural evidence at greater depths is scarce. Here we provide evidence for intense high-pressure abiotic methanogenesis by reduction of subducted ophicarbonates. Protracted (≥0.5–1 Ma), probably episodic infiltration of reduced fluids in the ophicarbonates and methanogenesis occurred from at least ∼40 km depth to ∼15–20 km depth. Textural, petrological and isotopic data indicate that methane reached saturation triggering the precipitation of graphitic C accompanied by dissolution of the precursor antigorite. Continuous infiltration of external reducing fluids caused additional methane production by interaction with the newly formed graphite. Alteration of high-pressure carbonate-bearing ultramafic rocks may represent an important source of abiotic methane, with strong implications for the mobility of deep C reservoirs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alteration of ultramafic rocks generates highly reducing fluids that, in the presence of C may yield hydrocarbons of purely abiotic origin1,2. Abiotic methanogenesis in ultramafic rocks has been shown at natural conditions spanning seafloor hydrothermalism, magmatism and on-land subaerial serpentinization3. This is an important process in geo-astrobiology, as it is considered as a source of prebiotic organic compounds on Earth and Mars and their possible role on the origin of life4. At shallow depth on Earth, serpentinite-hosted seeps can produce high methane (CH4) fluxes, and play an important role at the geo-bio-hydrosphere/atmosphere interface3,5,6. At greater depth, abiotic methanogenesis may occur as well and has the potential to be an important process controlling the redistribution of C reservoirs and the redox state of the mantle, including via the precipitation of condensed organic C molecules. Although the possibility for abiotic CH4 and other hydrocarbons to form at high-pressure conditions is demonstrated by experimental studies7,8,9, the geological conditions and processes at their origin, as well as their manifestations in the rock record, are still poorly constrained.

Subducted sections of altered oceanic mantle lithosphere represent suitable environments for the production of H2 and abiotic CH4 at high-pressure conditions, as they may contain both ultramafic minerals with a high reducing potential (for example, unaltered olivine), and carbonated lithologies10, also known as ophicarbonates11,12. So far, the role of ophicarbonates in the deep C cycle has been considered as negligible above depths exceeding 200 km in subduction zones10,11,13. However, this conclusion refers to the behaviour of these rocks under closed-system conditions, while their role in open systems affected by fluid percolation is still barely known.

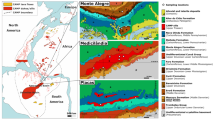

Metamorphosed ophicarbonates affected by fluid-rock interactions at high-pressure conditions provide the opportunity to assess whether H2 and abiotic CH4 are released at subduction zones, and to which extent. Here we present natural evidence for intense high-pressure abiotic methanogenesis, and related graphitization of ultramafic mantle rocks, induced by percolation of ultra-reduced fluids in metamorphosed ophicarbonates in the Lanzo peridotite massif, Italian Alps (Fig. 1). Alteration of carbonate-bearing ultramafic rocks in subduction zones, and plausibly other high-pressure settings, generates important fluxes of abiotic CH4 and can precipitate high amount of reduced C. Our finding may have significant impacts on our global understanding of the deep C cycle and deep hydrocarbon generations. These processes may have substantial consequences for the redox state of mantle rocks and magma generation, as well as for the mobility of reduced C species from deep reservoirs to shallow environments on Earth and possibly on other bodies of the Solar System, including the supply of pre-biotic molecules and nutrients to the biosphere, to gas reservoirs and to the atmosphere.

Note the fresh peridotite core surrounded by a pervasively serpentinized shell. Cf. Supplementary Fig. 1 for localization on a larger scale map.

Results

Geology of the Lanzo Massif and sample occurrence

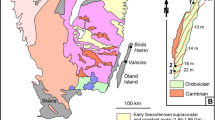

The Lanzo Massif is a large (∼150 km2) body of ultramafic rocks located in the internal part of the Western Italian Alps (Fig. 1). This body is a remnant of the Mesozoic slow-spreading Tethyan lithosphere that underwent peak eclogite-facies metamorphism during the Cenozoic Alpine subduction at ∼550–600 °C and 2–2.5 GPa (refs 14, 15). These ultramafic rocks experienced various interactions with fluids both during seafloor hydrothermalism and in the subduction zone, leading to large domains dominated by pervasive serpentinization (20–100 vol% serpentine)15,16,17. A large portion of the massif includes well-preserved peridotites (<20% serpentine) mainly comprising lherzolite with minor harzburgite and dunite18,19. The polyphase evolution of the Lanzo Massif resulted in a present-day structure consisting of a preserved peridotite core surrounded by a fully serpentinized shell (±carbonate and other alteration products; Fig. 1). Evidence for seafloor hydrothermalism, serpentinization and carbonation of the Lanzo peridotite has long been recognized and testified by typical products such as ophicarbonates, and reworking of this material in seafloor sedimentary deposits14,20. Subsequent serpentinization in the subduction zone is attested by additional replacement of primary (olivine, pyroxenes) and secondary (metamorphic olivine) phases by the high-pressure antigorite polysome15,16.

The studied samples belong to the northern part of the Lanzo Massif, within the serpentinized shell of the massif (Fig. 1). The area consists of almost fully serpentinized peridotites that locally preserve their primary mantle structures and fabrics. A body of ophicarbonate (Fig. 2a,b) occurs within the serpentinized peridotites. The ophicarbonate is characterized by variably deformed clasts of serpentinite, ranging in size from a few μm to ∼1 m, within a carbonate-dominated matrix (Fig. 2b–d). The northwestern side of the outcrop (left side of Fig. 2a) exhibits intense deformation along a ductile shear zone (ca. 2 m thick) that results in stretching and boudinage of the serpentinite clasts and intense veining. Various generations of veins (see their description below) and fractures develop both within the ophicarbonate body and from the body towards the surrounding serpentinites. The studied rocks, which hereafter we refer to as reacted ophicarbonates, are characterized by a remarkably dark colour on the hand specimen (Fig. 2c,d). Reacted ophicarbonates are often distributed along discrete layers within the ophicarbonate, interpreted as channelized fluid pathways (Fig. 2c), and occur both in the main shear zone and in the least deformed parts of the outcrop. The thickness of the reacted portions varies from a few centimeters to several meters.

(a) Main outcrop of ophicarbonate. The purple lines localize the boundaries of the ophicarbonate body and the main deformation zone. (b) Example of pristine ophicarbonate consisting of serpentinite clasts in a carbonate-dominated matrix. (c) Example of reacted ophicarbonate localized along a discrete layer. The layer is highlighted by the dashed lines and by the arrows. (d) Example of more pervasively reacted ophicarbonate. (e) Brucite-bearing zone (light brown) in the reacted ophicarbonate. (f) Brucite veins developing from the boundary of the ophicarbonate into the surrounding serpentinite. This geometrical relationship indicates that the fluid precipitating the brucite moved from the ophicarbonate to the serpentinite. The portion of reacted ophicarbonate (Oph) shown in the image contains abundant brucite, diopside and graphite (Fig. 3h). (g) Detail of the brucite veins fracturing the serpentinite in contact with the ophicarbonate. (h) Graphite vein cutting across the serpentinite massif surrounding the ophicarbonate. The photo shows the exposed vein wall; the vein is ∼1 mm thick. Scale bars are: (a) ∼1 m; (b,c,g,h) coin/marker is ∼2 cm in diameter, (f) head of the hammer is ∼10 cm long, (d,e) ∼5 cm. Brc, brucite; Cc, calcite; Grp, graphitic C; Srp, serpentine.

Petrology of the ophicarbonates and associated rocks

The ophicarbonates exhibit various degrees of transformation, from pristine ophicarbonates to extremely reacted ophicarbonates (Fig. 2b,d). Pristine ophicarbonates consist of serpentinite clasts dispersed in a calcite matrix (Fig. 3a). The clasts mainly consist of antigorite (the stable serpentine mineral at high pressures and temperatures metamorphic conditions), which is a low Al, 99 to 95% magnesian antigorite (Supplementary Table 1), as well as chlorite and magnetite. Some serpentinite clasts contain calcite and diopside. Reacted ophicarbonates exhibit similar features compared with pristine ophicarbonates, except for the occurrence of a ubiquitous dark rim coating the serpentinite clasts. The rims dominantly consist of graphitic C, together with variable amount of diopside and brucite (Figs 3d–h and 4). For simplicity, hereafter the graphitic C observed in our rocks will be referred to as graphite (see below for graphitic C characterization). The graphite-rich rim develops from the carbonate/serpentinite margins inward the clasts and in some cases almost fully replaces the serpentinite (Fig. 4a). Both clasts and isolated antigorite crystals are progressively replaced by the graphite-rich rims while preserving their original shapes (Fig. 4a,b).

(a–c) progressive degrees of transformation from the unreacted ophicarbonate (a) to the reacted one and (b) towards a rock entirely consisting of diopside+graphitic C (c). (d–e) Close-up of b showing the characteristic microstructure of reacted ophicarbonates. Note the dark, graphite-rich rim coating each serpentinite clast ((d) plane-polarized light; (e) cross-polarized light). (f–g) Backscattered electron scanning electron microscope (SEM) image (f) and relative X-ray emission map interpreted as a mineralogical map of a diopside+graphite reacted interface between a serpentinite clast (left) and Ca-carbonate (right). In f, dashed lines highlight the high-pressure fabric in the serpentinite, while the arrows indicate post-kinematic diopside crystals constraining the formation of the reaction rims to high-pressure conditions. (h) Brucite (light colours)+diopside+graphite (black) assemblage in reacted ophicarbonates. (i) Graphite veins cutting across the high-pressure fabrics in the serpentinite. Brc, brucite; Cc, calcite; Chl, chlorite; Di, diopside; Grp, graphitic C; Mt, magnetite; Srp, serpentine. Scale bars are: (a–c) 2 mm; (d,e,h) 500 μm; (f–g) 100 μm; (i) 5 mm.

(a) Reacted serpentinite clast partially replaced by graphite. (b) Partial replacement of individual antigorite flakes by graphitic C. (c) In situ focused ion beam (FIB) section cut across a graphitic C aggregate, showing a residual flake of serpentine in the middle. Pt coating: platinum deposited before FIB cutting. (d) Nodular graphite in a reaction rim. Polished thin section. (e) Serpentinite flake overgrown by graphite nodules (see Methods for sample preparation). (f) Dissolution pits in antigorite filled with graphitic C. (a,b,d) Backscatter electrons SEM image of polished thin sections. (c,e,f) Secondary electrons images. Abbreviations as in Fig. 3, Scale bars are: (a) 200 μm; (b) 20 μm; (c,d) 5 μm; (e,f) 10 μm.

The diopside and brucite content in the reaction rims is variable and, as a whole, decreases from the northwestern to the southwestern side of the outcrop (from left to right in Fig. 2a), with diopside-brucite-poor assemblages to the right and massive brucite-diopside mineralization to the left. Three end-member reaction products can be distinguished in the reacted rims based on the presence or absence of the above minerals (Figs 3 and 4): reacted rocks characterized by graphite, diopside and brucite; reacted rims containing graphite and variable amount of diopside; and reaction rims containing graphite only. Relict antigorite occurs in all the three above cases. Electron microscope imaging shows dissolution pits in the antigorite being filled with graphite (Fig. 4f). In some cases the replacement of antigorite by graphite is almost complete (Fig. 4c). This indicates that the graphite precipitation occurred by dissolution and microstructural replacement of the serpentinite clasts rather than by replacement of the neighboring carbonate. The third type, that is, reaction rims composed of graphite only, is of particular interest as the replacement of antigorite by graphite only testifies to extreme mass loss during fluid rock interactions and, therefore, to an open-system behaviour. This feature indicates that the three observed types of assemblages likely reflect different manifestation of the same fluid-mediated process, as detailed in the next sections. The graphite content in the rocks varies from 3 wt% in the least reacted samples to 13 wt% in the most extremely reacted samples (Supplementary Table 2). Petrographic observations suggest that the increase of graphite content generally corresponds to a decrease in the amount of the matrix carbonate. Although important variations of both the clast/matrix and the clast size may occur, the above features suggest significant carbonate consumption and volume decrease of the whole rock. Graphite has a nodular habit (∼5 μm in diameter, Fig. 4d–f): it occurs as individual nodules or aggregated nodules and it is well crystallized as indicated by Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 5), although the presence of a defect band indicates at least some structural disorder or the presence of heteroatoms such as O, H and N.

The spectrum of graphitic C is diagnostic of a well-crystallized structure. In particular, the characteristics of the well-developed graphite band (G band, 1,580 cm−1) compared with the defect band (D1 band, ∼1,350 cm−1) of graphitic C indicate a relatively high degree of crystallization78.

Magnetite is ubiquitous in both pristine and reacted ophicarbonates and occurs in both the ultramafic clasts and the carbonate matrix (Figs 3a and 5; Supplementary Fig. 2). However, the magnetite content is extremely variable in all rock types, from the carbonate-free serpentinite to the reacted and unreacted ophicarbonates. Furthermore, no structural relationship between the macro- and micro-scale reaction zones and the magnetite distribution is observed. In the reacted ophicarbonates, magnetite is locally inclusion rich. The inclusions comprise antigorite, graphite and fresh aragonite (high-pressure polymorph of Ca-carbonate) (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 2).

Two remarkable types of vein occur in the studied rocks, that is, brucite and graphite veins. In the northwestern, brucite-diopside-rich part of the outcrop (left side of Fig. 2a), the ophicarbonate is in contact with the host serpentinite. A complex network of brucite-rich veins, up to 10–15 cm in thickness, develops from the ophicarbonate into the serpentinite (Fig. 2f,g). The brucite in the veins is generally fresh (Fig. 5), although advanced conversion of brucite into serpentine+magnetite21 is locally observed. Graphite veins also develop from the ophicarbonate into the surrounding serpentinite. Microstructural relationships indicate that the graphite veins cut across the high-pressure, antigorite-bearing schistosity, or are parallelized to it by subsequent deformation (Figs 2h and 3i). These chronological relations indicate that graphite precipitation occurred at high-pressure conditions in the antigorite stability field, and rule out the possibility that graphite formed earlier, for example, during seafloor hydrothermalism. Some veins form discrete surfaces that can be followed continuously for about 15 m in the serpentinite before tapering out. Graphite veins in the serpentinite were found up to ca. 250 m from the studied ophicarbonate body.

Fluid inclusions are widespread in the matrix calcite (Fig. 6a,b). In several cases, the fluid inclusions are aligned along fan-shaped trails22 that develop from the reacted rims into the matrix carbonate (Fig. 6a,b). In this respect, these microstructures are analogous to the mechanism of pseudosecondary fluid inclusion formation23,24 and suggest that the fluid was generated in the reacted domains along the clast-matrix interface and then instantaneously injected into the matrix carbonate along new-forming cracks. Raman spectroscopy was used to determine the composition of fluid inclusions. Most fluid inclusions are CH4-H2-rich, whereas others contain H2O and, more rarely graphite (Fig. 6; Supplementary Fig. 2). The H2O-bearing clusters of fluid inclusion are generally associated to graphite-free serpentinite clasts in partially reacted samples. Conversely, fluid inclusions close to graphite-rich rims are generally richer in CH4, although some exceptions were found. Some fluid inclusions contain CH4, H2O±graphite±H2, and are microstructurally older then or contemporaneous with the gaseous ones. The large diversity of CH4-bearing (±H2O, ±graphite) fluid inclusions suggests that CH4 was produced by different fluid/rock processes and ratios, and probably at different conditions of pressure and temperature. In most cases, no relationship is observed between CH4-H2 fluid inclusion trails and the decompressive aragonite-to-calcite conversion in the matrix. However, in some cases, evidence for fluid inclusion trails intersecting and displacing twinning lamellae in matrix calcite is found (Fig. 6d). This microstructural relationship suggests that CH4 was still produced within the calcite stability field.

(a,b) Pseudosecondary trails of CH4-H2 fluid inclusions radiating from a partially reacted serpentinite clast into the carbonate matrix. Note that the fluid inclusion trails propagate only from the graphite-rich portion of the clast (upper side). (c) CH4-H2O-H2-graphite fluid inclusions (see also Supplementary Fig. 2). (d) Fluid inclusions displacing the twinning lamellae in the matrix calcite, thus postdating at least some CH4 release to the calcite stability field. (e) Raman spectra of CH4-H2 fluid inclusions (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for Raman map of Graphite-bearing fluid inclusions). Abbreviations as in Fig. 3. Scale bars are: (a,d) 200 μm; (b) 100 μm; (c) 10 μm.

Last, some isolated trails of H2O-rich fluid inclusions also occur in the rock but appear structurally late and crosscut the CH4-bearing clusters.

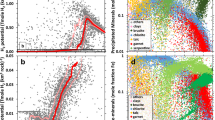

Carbonate and graphite δ13C composition

We analysed the δ13C (reported versus PeeDee Belemnite standard -PDB-) composition of carbonate and graphite in samples affected by different degrees of transformation, the latter being defined for simplicity by the amount of graphite in the rock. The Ca-carbonate in the ophicarbonates has δ13C values ranging from ∼2–3‰ in the least reacted samples (that is, lowest or null graphite amount) to ∼8‰ in the most reacted ones (Fig. 7; Supplementary Table 2). The values in the least reacted samples are compatible with a typical marine source (−3/+3‰)25, and match the composition of subducted ophicarbonates reequilibrated under closed system conditions13. The δ13C increase of residual carbonate in the reacted rocks does not match the range of typical carbonates of marine origin, and clearly reflects the effect of the fluid–rock interactions. This shift may have different origins. The isotopic re-equilibration during metamorphism of marine carbonate with a reduced C of biogenic origin (for example, δ13C=−25‰) would lead to a decrease in the carbonate δ13C value by considering a simple isotopic mass balance26. CO2-producing decarbonation reactions between carbonates and silicates have a similar effect27. Reduction of carbonates by H2-bearing fluids is expected to increase the δ13C value of the residual carbonate28, as also suggested by the negative signature of abiotic CH4 (refs 3, 29). Therefore, the δ13C increase in the reacted samples is most plausibly representative of reducing conditions and production of CH4 rather than decarbonation and release of CO2, which would have left a 13C-depleted carbonate. These data, together with the microstructural constraints from fluid inclusions, indicate that the CH4 was produced within the ophicarbonate by carbonate reduction.

The δ13C composition of natural diamonds31 is also reported for reference.

The δ13C of graphitic C ranges from∼−5 to ∼−8‰ (Fig. 7; Supplementary Table 2). These values are not consistent with subducted marine biogenic organic matter, that typically ranges between −25 and −10‰ in both subducted sedimentary rocks and oceanic crust rocks10,13,26,30, where the highest values are characteristic of metamorphic isotopic equilibration between organic C and carbonates in rocks with very high carbonate/organic C ratios. Organic C in seafloor serpentinites10 also fall in this range, and can thus be ruled out as a possible origin for the graphitic C analysed in our rocks, even in the case of carbonate-organic C re-equilibration. In that case, the higher measured values of −5‰ are characteristic of metamorphic isotopic equilibration between organic C and carbonates in rocks with very high carbonate/organic C ratios, which does not match our data. The graphite δ13C values in the reacted ophicarbonates are comparable with mantle C values, typically −8/−5‰ (ref. 31), although our data indicate that the hypothesis of a mantle C source for our rocks can be ruled out. In particular, the graphite distribution in the studied rocks is clearly related to the occurrence of ophicarbonates of plausible marine origin. Moreover, the graphite veins crosscutting the serpentinite fabrics are a strong evidence for syn-subduction/accretion C mobilization within the Alpine orogenic prism. A mantle-derived origin for these intense fluid circulations would have therefore affected the whole Alpine structure, which has not been documented so far and appears a less plausible configuration in our case.

The most plausible hypothesis for the origin of graphite is saturation of carbonate-derived abiotic CH4. To provide additional support for this hypothesis, we used the measured δ13C values to test the graphite formation from saturation of CH4 produced via two alternative reaction pathways, that is, Fischer-Tropsch-type (FTT) reactions involving reduction of CO2, produced during devolatilization of carbonate with marine signature, into CH4, and direct carbonate methanation3,7,32. It is worth noting that these two alternative processes represent intermediate stages of a more complex mechanism detailed in the next section. During FTT methanogenesis, kinetically controlled isotopic fractionation may occur, as shown experimentally under hydrothermal conditions33,34. The role of kinetically controlled fractionation in our samples cannot be clearly established because the specific reaction (for example, FTT or carbonate methanation) is unknown. Moreover, the kinetic fractionation coefficients are available only for the first step of reaction (for example, conversion of CO2 to CH4 (refs 33, 34)) and are not known for the CH4 to graphite reaction. Therefore, to provide first-order estimates, we used equilibrium fractionation factors between the primary carbonate and the graphite, through the two alternative intermediate fluid paths (Supplementary Table 3). Considering a possible kinetic fractionation, the values obtained at equilibrium are considered as minimum values33,34. At the estimated metamorphic temperatures for these rocks (300–450 °C, see next section), this approach yields graphite values consistent with the measured ones (δ13C measured :−5/−8‰, calculated :−6/−9‰, for an initial carbonate at 2‰), but does not allow further discrimination between the two alternative mechanisms of CH4 generation (see Methods). Moreover, the agreement between the calculated values at equilibrium and the measured values may indicate a non-kinetic methanogenetic process at high-pressure conditions. If confirmed by further investigations, our case study would be the first natural evidence for carbonate methanation.

In summary, the isotopic data indicate that high-pressure abiotic CH4 and graphite with mantle-like δ13C compositions can form by in situ reduction of subducted marine ophicarbonates, without any contribution of mantle C. Similar processes may participate in the precipitation of mantle diamonds with this isotopic signature at greater depths31,35, or nanodiamonds in the graphite stability field36.

Methane and graphite forming processes

The presence of unreacted ophicarbonate domains, together with the field, isotopic and microstructural data on fluid inclusions, indicate that CH4 and graphite formation was controlled by fluid-mediated redox reactions rather than regional variations in pressure and temperature. As emphasized in the previous section, carbonate reduction appears as the leading mechanism for the generation of CH4 and graphite in the Lanzo rocks, although the exact path (for example, FTT, carbonate methanation) cannot be determined by the available data. Nevertheless, the field and microscopic observations indicate the necessity of antigorite for both CH4 generation and the resulting graphite precipitation. No graphite was found in the absence of antigorite, with the exception of the one occurring in some CH4-bearing fluid inclusions. Although the ubiquitous presence of graphite in the reaction rims indicates that the whole outcrop was governed by the same process, variable mineral modes (graphite±diopside±brucite) reflect the coexistence of metamorphic (isochemical) and metasomatic (non-isochemical) processes at various scales to define a reaction mechanism37.

The occurrence of graphite as the only phase replacing antigorite in some reacted rims clearly indicates that the CH4 and graphite-forming process was in many cases dominated by an open-system behaviour. Silicate dissolution and significant release in the fluid of mainly Si, Mg±Fe cations from antigorite and Ca from the carbonate was likely a dominant process during the fluid–rock interactions, and probably prevented systematic precipitation of phases such as diopside and brucite (see also Malvoisin38). Owing to the mineralogical variability within and between reacted rims, therefore, any balanced reaction accounting for dissolved electrolytes would have a local meaning. Nevertheless, the local graphite+brucite+diopside assemblages suggest the preservation of rather closed, isochemical domains, and allow summarizing the above observations at the scale of the outcrop by the following generic, fluid-mediated redox reaction (Fig. 8):

The cartoon summarizes the petrologic process of CH4 generation mediated by infiltration of H2-rich fluids resulting from high-pressure serpentinization of subducted peridotites. An unreacted ophicarbonate (lower part) is also provided for reference. Note that the cartoon does not include stoichiometric precipitation of products as in Reaction (1), but partial mass loss as suggested by our data (cf. text for details).

As supported by the isotopic data (see previous section), the precipitation of graphite was controlled by saturation of C in the reduced COH fluid39,40, through the same conceptual mechanism responsible for graphite precipitation after carbonate reduction in other metamorphic settings39,41,42. Although this generic reaction pathway (Reaction (1) followed by graphite precipitation from C saturation in the fluid) best combines the collected data, other reaction pathways including more complex metastable intermediate fluid species43 cannot be excluded, but cannot be resolved with the available data.

Reaction (1) produces CH4 and H2O, which were both observed in some fluid inclusions. As soon as the reaction rim is formed, the presence of the graphite coating may inhibit the reaction of carbonate+antigorite with the external reducing fluid. In this case, episodic infiltration of H2-rich fluids in the reacted ophicarbonate may have released additional CH4 following the reaction:

This process of protracted, episodic H2 infiltration and CH4 production by Reaction (2) may explain the presence of pseudosecondary CH4-H2 fluid inclusions developing from graphite-rich rims (Figs 6a,b and 8). As in this case the reactant graphite is abiotic in origin, the CH4 resulting from Reaction (2) is also abiotic.

The local manifestation of Reaction (1) in some reaction rims allows thermodynamic calculations to be done to estimate the range of pressure, temperature and redox conditions at which this reaction can occur (Fig. 9). Owing to the low and variable Fe content in the antigorite, the calculation was performed in a simplified Ca-Mg-Si-C-O-H system to minimize the compositional variability of the reactant and product mineralogy (see Methods). The microstructural and petrographic study indicates that graphite precipitation was already active in the aragonite stability field, as testified by graphite-aragonite inclusions in the magnetite. This constrains the minimum pressure-temperature conditions for Reaction (1) to pressures >∼1 GPa and temperatures >∼370 °C along the predicted path of the Lanzo Massif15 (Fig. 9a). The thermodynamic modelling also indicates that the maximum temperature conditions for Reaction (1) to occur are ∼500 °C in the pressure range experienced by the Lanzo Massif during the Alpine subduction (≤2.5 GPa). Above these conditions, antigorite breaks down in favour of olivine, and leads to mineral reactions that were not observed in our samples. We calculated the speciation of the fluid in equilibrium with Reaction (1) as a function of the pressure–temperature path experienced by the Lanzo Massif. Along the prograde path up to 2 GPa and 500 °C, that is, near-peak conditions, the minimum XO (nO/(nO+nH), where n is the number of moles of either O or H (ref. 44)) values required for the reaction to happen are close to that of pure water (Supplementary Fig. 3). This is similar to estimates for prograde carbonate reduction in the presence of quartz documented in blueschist-facies metasedimentary rocks28,41. With decreasing pressure-temperature conditions along the exhumation path of the Lanzo Massif, the reaction requires more reducing conditions (Fig. 9a,b). This corresponds to a progressive increase of the molar fraction of CH4 and H2 in the fluid relative to H2O. In the calcite stability field (P<0.8 GPa, T<380 °C) the fluid in equilibrium with Reaction (1) has XO<0.03, and consists of CH4 with minor H2 and H2O. At ∼300 °C and 0.5 GPa, the equilibrium fluid is almost pure CH4 (Fig. 9b). The modelling results at these conditions are therefore in good agreement with the measured CH4-H2 composition of fluid inclusions post-dating the aragonite-calcite conversion in reacted ophicarbonates during retrograde metamorphic conditions. The thermodynamic results also show that CH4 production via direct reduction of carbonate in the absence of antigorite requires extremely reducing conditions (XO=0) that were not reached in our samples, and support that the generation of CH4 was initially possible thanks to the presence of antigorite through Reaction (1).

(a) Thermodynamic models in the Ca-Mg-Si-C-O-H system (cf. Methods for details on the model construction) for Reaction (1). Each curve represents the same reaction calculated at different temperature, as a function of pressure and XO. The reaction products are to the higher-pressure side of the curves. The black boxes represent the intercepts of pressure and temperature along the exhumation path of the Lanzo Massif (long gray arrow). (b) Chemical concentration of the main fluid species at 350 °C and 0.7 GPa as a function of XO. Yi refers to the molar proportion of the different species in the fluid.

Carbon saturation in the presence of magnetite in the reacted ophicarbonates of the Lanzo Massif constrains fO2 to values as low as −29 to −37 log units (∼FMQ−3/−6 at the considered pressure–temperature conditions, Supplementary Fig. 4). These values are consistent with past estimates on the redox state of C-free subducted serpentinites45.

H2 sources and fluxes of high-pressure abiotic CH4

A major condition at the origin of the observed deep abiotic methanogenesis is the need for external H2 infiltration. Hydroxylation of Fe2+-bearing minerals, most notably olivine, is the most common source of H2 in ultramafic rocks. Ophicarbonates forming by alteration of mantle rock at the seafloor are most commonly fully serpentinized, indicating that the source of reducing fluids in the subduction zone was probably not the ophicarbonate itself. In our case study, the most plausible source of H2 for Reaction (1) was the hydroxylation of the preserved peridotite core of the Lanzo Massif in the subduction zone. The Lanzo Massif contains large volumes of fresh peridotites that largely escaped serpentinization at the seafloor18,19, thus providing a high reducing potential during subduction metamorphism in the presence of water. Moreover, although the studied samples belong to the extensively serpentinized shell of the massif, relicts of fresh olivine and pyroxenes were found in the serpentinite. Evidence for serpentinization of relict primary phases during subduction has been reported in the Lanzo rocks15,16, part of which may have taken place at the estimated conditions for Reaction (1) during exhumation (Fig. 9). Free water availability and hydration during exhumation of high-pressure rocks is indeed very common46. Owing to the large fresh peridotite reservoir, it is probable that this hydration stage occurred under water-undersaturated conditions at the scale of the massif, thus creating suitable conditions for the release of dry H2 fluids. An important analogy can be drawn with the case of carbonate reduction in metasedimentary rocks in Corsica28,41. Also in that case, bodies of only partially serpentinized peridotite occur in the close proximity to the reacted metasediments47. The preservation of unaltered or partially serpentinized peridotite domains within subducted ultramafic rocks seems, therefore, to represent a key geological condition for deep abiotic methanogenesis in subducted slabs.

We calculated hypothetical paleofluxes of abiotic CH4 produced by fluid-induced redox alteration in our rocks (see Methods). For the most reacted samples, the minimum amount of CH4 required to precipitate the observed graphite concentrations (∼10 wt%, Supplementary Table 2) reaches ∼350 kg m−3. These are clearly the most conservative estimates, as evidence of additional CH4 is testified by the CH4-bearing fluid inclusions and by the graphite-bearing veins propagating from the ophicarbonate into the surrounding serpentinite. More accurate values would require definition of graphite precipitation rates that cannot be established by equilibrium models.

A rough mass balance calculation indicates that channelized H2 produced by ∼50–300 m3 of fresh to fully serpentinized peridotite is required to produce the conservative CH4 fluxes reported above (see Methods). These values support the hypothesis of percolation of channelized reducing fluids of external origin in the studied ophicarbonates.

Graphite-CH4-bearing fluid inclusions in matrix calcite indicate that CH4 production was maintained during retrogression from the aragonite to the calcite stability field. Considering decompression from ∼1 to 0.5 GPa across the aragonite-calcite transition (Fig. 9a), and the available exhumation rates for the high-pressure rocks of the Western Alps (1.6–3.4 cm per year (ref. 48)), a conservative estimate indicates that (possibly pulsed) methanogenesis was maintained over at least 0.5–1 Myr ago during decompression. The occurrence of graphite-bearing veins cutting across carbonate-free serpentinites supports the hypothesis of high CH4 fluxes.

Discussion

Although subduction zone fluids are believed to be dominantly aqueous49, natural evidence for the generation of reduced fluids in subduction zone ultramafic systems exists50,51,52,53. However, the abiotic versus biotic nature of hydrocarbons (mostly CH4) associated with these fluids is not clearly constrained, and currently no well-established natural processes generating abiotic CH4 in ultramafic rocks at high-pressure conditions are established. To sum-up, our data demonstrate that alteration of ophicarbonates at forearc conditions can produce very high amounts of abiotic CH4 in subduction zone fluids through the two key following processes (Fig. 8). Subducted partially serpentinized peridotites (>>0.21 km3 per year; see Methods) react with aqueous fluids leading to high-pressure serpentinization and generation of H2-rich fluids. These fluids are then channelized and react with carbonate-bearing ultramafic rocks (ophicarbonates) triggering in situ carbonate reduction in the presence of antigorite and generation of abiotic CH4.

While CH4 is produced, if C saturation in the fluid is reached, precipitation of abiotic graphitic C may sequester part of the produced CH4, whereas another part can migrate towards external reservoirs. Protracted, episodic infiltration of H2-rich fluids and interaction with the graphite caused additional production of abiotic CH4. The open-system behaviour of the protracted fluid–rock interactions resulted in local transport of Mg, Ca, Si and Fe and precipitation of brucite- and diopside-rich assemblages in the contact zone between the ophicarbonate and the serpentinite.

Previous studies considered the role of subducted ophicarbonates in the recycling of C to be negligible at forearc depths10,11,13. However, these studies refer to either numerical or natural closed systems unaffected by infiltration of externally derived reduced fluids. This type of fluid can be very common in subducting slabs owing to the only partial (slow-spreading crust) or even negligible (intermediate- to fast-spreading crust) serpentinization of mantle rocks entering the subduction zone. There is ample geophysical and numerical modelling evidence for intense serpentinization of both subducted oceanic lithosphere and the overlying mantle wedge in subduction zones from the trench (bending-related serpentinization54) to much greater depths (serpentinization by ascending aqueous fluids55) along the plate interface. Considering a most conservative configuration of subduction of 100% slow-spreading-type crust (highest serpentinization rates; min. 0.21 km3 of fresh peridotite accreted annually6), and the widespread availability of C in subducted ultramafic rocks (2.04 Mt C annually10), full serpentinization of partially serpentinized peridotites during subduction potentially releases >0.8 Mt H2 and >1.5 Mt CH4 per year (Methods). This value can greatly increase in the case of subduction of intermediate to fast-spreading crust—expected to be dominant in present-day subduction zones—where only very little seafloor serpentinization occurs.

Infiltration of these reduced fluids in subducted sedimentary suites may enhance additional carbonate reduction and carbonate dissolution28,32,41. Purely abiotic methanogenesis is likely to occur also in the forearc mantle wedge overlying subducting slabs, where hydration and serpentinization is demonstrated by geophysical evidence56. Although the generation of H2 by serpentinization at high-temperature conditions (400–600 °C) has been questioned57 our data suggest that significant H2 production does occur during serpentinization in the subduction zones at relatively high temperature (∼400 °C), and support the possibility for this process to happen in mantle peridotites ascribed to the mantle wedge51,58. Interaction of mantle wedge H2 with the large amounts of slab-derived carbonic fluids59 potentially generates 0.13 to 2.5 Mt CH4 per year in the forearc mantle wedge above subduction zones. These values are similar to the ones estimated for abiotic CH4 production by serpentinization at (sub)seafloor conditions (0.2–2.3 Mt per year (ref. 60)). Together with mid-ocean ridges and on-land processes3, deep serpentinization may represent significant sources of abiotic CH4 on Earth (global biotic CH4 fluxes are 60 Mt per year (ref. 3)), and may possibly account for the episodic release of CH4 on other planets such as Mars where deep serpentinization may have occurred61,62. These C-bearing reduced fluids may be fully transferred to shallower reservoirs and possibly contribute to greenhouse emissions, or can be modulated by graphite and/or diamond precipitation (up to 0.1–1.9 Mt per year C bound in ultramafic rocks by considering full conversion of CH4 into graphite) or fluid re-speciation at depth.

The precipitation of high amount of graphite imparts a strong buffering potential to subducted ultramafic rocks, with consequences for the redox state of mantle rocks and partial melting63. High amount of graphitic C in high-pressure serpentinites represents an additional source of abiotic CH4 genesis in the presence of H2O (ref. 40) or H2 (Reaction (2)). Graphite may be used as a marker of past abiotic methanogenesis in ultramafic rocks from a wide range of geological conditions, although its precipitation is not expected to be systematic during high-pressure methanogenesis, and abiotic methanogenesis is not the only mechanism to precipitate graphitic C in ultramafic rocks. Graphite in serpentinites has been reported from different settings. Recent works report traces of organic C in ocean-floor serpentinites and associated mafic rocks, and alternatively favour biotic or abiotic processes64,65. In metamorphic terranes, traces of organic C in serpentinites have been interpreted as a relict of seafloor hydrothermalism66. Graphite in blueschist-facies metasomatized metasediments was recently interpreted as the result of carbonate reduction by serpentinite-derived aqueous fluids28,41. Carbonaceous material and nanodiamonds have been reported in shallow, lizardite-bearing serpentinized mantle xenoliths36. Pasteris67 reported graphite formed by postmagmatic aqueous serpentinization of olivine in kimberlites. These studies, together with our data, suggest that deep abiotic methanogenesis (and possibly other types of deep hydrocarbons9) by high-pressure serpentinization may be a more common process than previously thought, with potential implications for geo-astrobiological (for example, Archean, Mars) detection and search of both abiotic and biotic C compounds.

Methods

Samples

Samples were collected in the Lanzo peridotite massif (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. 1). Sixty-seven samples were collected from three main outcrops during four surveys. Only fresh samples were collected. Thin sections (30 μm thick per 100 μm for fluid inclusion study) were prepared for petrographic inspection and photography using a petrographic microscope, as well as for scanning electron microscopy, electron microprobe and Raman spectroscopy. Specimens for chemical analyses were cut from the rock samples using a diamond saw and then crushed and pulverized. Samples for morphology imaging (Fig. 4c,e and f) were etched by HCl (20 mol l−1).

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra were obtained using a Renishaw InVIA Reflex microspectrometer using a 532 nm laser at IMPMC, Paris. Measurements were done on polished thin sections (30 μm thick for mineral analysis/100 μm for fluid inclusion analysis). The laser was focused on the sample by a DMLM Leica microscope with a 100 × objective (numerical aperture (NA)=0.85). Different laser powers were set from an initial 150 mw source for the different minerals or fluid inclusions: graphite (∼1%), silicates (∼50%), carbonates (∼50%), fluid inclusions (∼100%). Five acquisitions of 10 s were performed for each analysis. The signal was dispersed using a 1,800 gr mm−1 grating and finally analysed by a Peltier cooled RENCAM CCD detector. The spectrometer was calibrated with silicon standard. The spectrometer was calibrated with a silicon standard. The composite Raman map in Supplementary Fig. 2e was performed using the same setup with an acquisition time of 1.5 s per spot (1 μm grid), and results from the superposition of three maps performed at different wavenumber ranges and with different laser powers, in the order: graphite, silicates+carbonates, fluid inclusions. The map was performed at ca. 5 μm below the surface of the sample.

The brucite spectrum was acquired on a Xplora Horiba Jobin-Yvon using a 532 nm laser at IMPMC (five acquisitions of 12 s each).

Carbon stable isotopes and graphite concentration

Samples for C stable isotope geochemistry were first cut to isolate portions unaffected by weathering and surface organic contaminations such as biomass, and then crushed and pulverized with an agate mortar. The possible effect of organic contaminations by groundwater circulation was considered to be negligible owing to the very high amount of graphitic C in the samples. Analyses of total organic carbon (TOC) were performed on aliquots of dried, decarbonated samples (HCl, 6 mol l−1, attacked at ambient temperature for one night) using a Flash EA1112 elemental analyser coupled to a Thermo Finnigan DELTA plus XP isotope ratio mass spectrometer via a ConFlo IV interface at IPGP, Paris. Aliquots of the companion, non-decarbonated sample were also analysed for Total Carbon (TC=TIC+TOC) (Supplementary Table 2). Three internal standards are used to calculate the δ13C of samples and an internal standard with 5 different amounts is used to estimate the concentration of C (wt%). Reproducibility of replicated standards is±0.1‰ for δ13C and expressed in the PDB scale. Three replicates were analysed for each sample.

The carbonate concentration and isotopic composition of calcite (δ13C) were measured by AP2003 continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer. Between 2 and 3 mg of samples were loaded in vials; three standards of pure calcite were also used for calibration of both concentration and isotopic composition. After flushing with ultrapure Helium, orthophosphoric acid (H3PO4) was introduced in each tube to produce gaseous CO2. After 4 h of reaction at ambient temperature, calcite is completely transformed into CO2; gases are then transferred into mass spectrometer for analysis. To improve the precision of the measurements, each analysis is repeated four times for each vial; and each sample analysed twice. The isotopic 13C/12C ratios are expressed using the conventional δ-notation versus PDB international standard. The precision is 0.1‰ for δ13C, and 10% for the carbonate content.

Scanning electron microscopy and focused ion beam

We used a Zeiss Ultra 55 field emission gun SEM operated at 2 to 15 kV at IMPMC, Paris. Backscattered electron (BSE) mode was used to investigate chemical heterogeneities using an Angle Selective Backscattered Detector (AsB, working distance 7.5 mm) or an energy selective backscattered detector (EsB). Morphology imaging was performed using an InLens detector (working distance 2–3 mm). Energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDXS) maps were acquired using an EDXS QUANTAX system equipped with a silicon drift detector XFlash 4010 (Bruker). Data were processed with the software Esprit (Bruker). Focused ion beam (FIB) milling was used to produce ultra-thin sample sections (Fig. 5d) on a Zeiss neon EesB40 FIB/FEG-SEM system (IMPMC, Paris). A FIB-assisted Pt deposit was first made. A 30 kV Ga+ beam operated at ca 5 nA was then used for the initial milling steps, consisting in rough excavations from both sides of the thin foil. An in situ micromanipulator was attached to the foil by FIB-assisted platinum deposition before separation of the foil (at ca 100 pA). The thin foil was transferred to a TEM grid and welded to it. The thinning of the ultra-thin foil was performed with the beam operated at a ca 100 pA current. A last cleaning step was performed at low acceleration tension (ca 3 kV).

Electron microprobe analysis

The major elements mineral analyses were performed using a Cameca S-Five and a Cameca-100 electron microprobes (Camparis, Université Paris 6). Classical analytical conditions were adopted for spot analyses (15 kV, 10 nA, wavelength-dispersive spectroscopy (WDS) mode), using Fe2O3 (Fe), MnTiO3 (Mn, Ti), diopside (Mg, Si), orthoclase (Al, K), anorthite (Ca) and albite (Na) as standards. Quantifications were derived from the automated Cameca ZAF quantification procedure.

Thermodynamic modelling

Thermodynamic modelling was done using the Perple_X software package (version 6.7)68 and the internally consistent thermodynamic database of Holland & Powell69. Figure 9b was constructed using the FLUIDS routine. For Supplementary Fig. 4b, an input file was generated by BUILD routine, and then processed by VERTEX and PSVDRAW routines. Supplementary Fig. 3b results from the superposition of four calculations performed at different temperatures. Reaction (1) was modeled in the simplified Ca-Mg-Si system (note that in Supplementary Fig. 3b, the equilibrium between metallic iron (I) and magnetite (M) is only indicated as a reference—IM buffer) in COH fluid-saturated conditions, and the GCOH equation of state for graphite-saturated systems was used44. The aim of these calculations was to explore the conditions for diopside+graphite assemblages to form from antigorite+calcite assemblages, as suggested by the detailed mineralogical and microstructural investigations presented in the text. However, this is a simplification of the system, as antigorite contains aluminum (1.5<Al2O3 wt%<5.0) and iron (2.7<FeOtot wt%<4.8) and it is associated with accessory chlorite (with possible local serpentine-chlorite interstratifications). Concerning aluminum, its incorporation to the thermodynamic calculations shifts the location of the terminal reaction for antigorite by only 30 °C, and it is expected that the effect would be similar for Reaction (1) of our study (J.A. Padrón-Navarta, personal communication). Despite the lack of Fe-rich phases in reacted ophicarbonate clasts, iron certainly played a role in the whole system. Notably, the production of hydrogen involved Fe2+ oxidation by water, but it is inferred to have taken place predominantly in the fresh peridotite core of the Lanzo Massif rather than in the already serpentinized ophicarbonates. More locally, the partial dissolution of antigorite observed in reacted ophicarbonates would have resulted in a release of Fe (likely Fe2+) in the fluid, which probably mostly re-precipitated in veins as magnetite and Fe-bearing brucite (up to 8 wt% FeO in brucite). Small shifts in P, T and fO2 estimates would be expected from the incorporation of Fe in the model. Indeed, such effects have been demonstrated in the case of chlorite solid solutions, which have been fully implemented in the Holland and Powell thermodynamic database70,71,72. However, it would be beyond the scope of the present study to take Fe2+ and Fe3+ into account in thermodynamic calculations. First, it is important to note that the incorporation of Fe2+-Fe3+-Mg-Al serpentines in internally consistent database such as Holland and Powell’s is still incomplete. Also, our preliminary investigations suggest large Fe3+/Fetot variations in antigorite-bearing assemblages, down to the sub-micron scale. Finally, micron-scale evaluation of the changes in composition of antigorite shows a lack of correlation between the Fe content and the distribution of reacted/unreacted domains in ophicarbonates. Therefore, evaluating the systematic changes in the Fe content and the valence state of Fe of antigorite in reacted ophicarbonates is the subject of ongoing work and is expected to bring refinements of the present, first order model, but it is not expected to change its main conclusions.

Mechanism of abiotic CH4 genesis for isotopic calculations

To test the relation between CH4 and graphite, we tested two different reactions pathways for conversion of carbonates into CH4, and then into graphite after C saturation of the intermediate COH fluid. Note that the two mechanisms below represents intermediate stages within a more complex process illustrated by generic Reaction (1), and are not relevant to the presented case study in the absence of antigorite (see main text). The results and discussion related to this method can be found in the main text and in Supplementary Table 3.

Most studies dealing with methanogenesis at low-pressure conditions refer to Fischer-Trospch reactions like73:

In this case, carbonate reduction produces CO2, and then CO2 converts to CH4 by Reaction (3).

Another possibility is direct carbonate methanation via reactions such as (refs 3, 7):

Carbon saturation in the produced CH4-rich fluid then precipitates graphite.

Mass balance

Amount of CH4 needed to precipitate the observed graphite concentration in the sample. We selected an average graphite concentration of 10 wt% from the graphite-richest samples (Supplementary Table 2). This was converted to CH4 per m3 by considering a precursor rock consisting of equal proportions of serpentine and carbonate with density of 2.6 g cm−3.

Amount of ultramafic rock needed to reduce the system. We considered two end-member ultramafic rocks, that is, a pristine peridotite fully consisting of olivine, and a fully serpentinized peridotite. In the first case, we considered the serpentinization reaction73:

The stoichiometry of this reaction was used to calculate the amount of olivine (peridotite) needed to reduce 1 g of CaCO3 following Reaction (4). The volume of peridotite was then calculated by taking the amount of CaCO3 reduced to produce the measured graphite amount. This calculation gave ca. 50 m3 of fresh peridotite.

In the second case, we used the estimate provided by Malvoisin et al.41, who calculated that 350 g of fully serpentinized rock initially equilibrated at FMQ-4 (values that fits the range of fO2 calculated for our rocks) are needed to reduce 1 g of Ca-carbonate at similar pressure and temperature conditions. In this case, the calculation gave a volume of serpentinite of ca. 290 m3.

Duration of methanogenesis during exhumation

We considered a Δ pressure of 0.5 GPa from calcite to aragonite stability conditions as shown in Fig. 9. This pressure was then converted into depth by considering all pressures as lithostatic pressure (0.1 GPa=3.5 km). Estimated exhumation rates of 3.4 and 1.6 cm per year for high-pressure rocks in the western Alps48 were then considered.

Carbon stable isotope fractionation

We used fractionation factors between CaCO3, CO2, CH4 and graphite after Bottinga74 and Ohmoto & Rye75. We calculated the fractionation factors resulting from graphite precipitation after either CO2 hydrogenation and direct carbonate methanation (see below). In both cases, we used starting initial CaCO3 with δ13C at 2/−2‰ (most common values of calcite in ophicarbonates76, also matching our least reacted samples) (Supplementary Table 3). For CO2 hydrogenation, the calculation was done by considering isotopic equilibria on three steps: (i) CaCO3-CO2; (ii) CO2-CH4; and (iii) CH4-graphite. For direct carbonate methanation, the calculation was done by considering isotopic equilibria on two steps: (i) CaCO3-CH4; (ii) CH4-graphite. Each calculation was done for two different temperatures of 450 and 300 °C.

CH4 fluxes from serpentinization of the subducting slab

To estimate conservative values, we used the amount of ultramafic rocks accreted annually (0.39 km3 per year) and the amount of serpentinized rocks (0.18 km3 per year) at slow-spreading centers from Cannat et al.6. This gives an amount of 0.21 km3 per year of fresh peridotite unaffected by serpentinization per year. This rate was assumed to be equal to a hypothetic (most conservative) case of subduction of 100% slow-spreading crust. Considering 0.21 km3 per year of fresh peridotite subducted annually, a density of 2,540 kg m−3, and the amount of H2 released by serpentinization from Reaction (5), and the CH4-producing Reactions (3–4), the most conservative calculation indicates that serpentinization of the subducted lithospheric mantle may release >0.8 Mt H2 and >1.5 Mt CH4 per year. The estimated amount of subducted C in serpentinites (2.04 Mt per year) is largely sufficient to produce the above CH4 fluxes. In detail, full conversion of C in subducted serpentinites would produce 2.72 Mt CH4 per year, which is much higher than the estimate proposed above (1.5 Mt CH4 per year). Subduction of fast, spreading crust would yield to much higher values owing to the much lesser amount of serpentinization during seafloor alteration.

CH4 fluid fluxes in the mantle wedge

We used fluxes of C released from subducting slabs to the overlying mantle wedge from Kelemen and Manning59 down to 2 GPa (up to 1.9 Mt per year). This value was then converted to CH4. The amount of H2 needed to convert C into CH4 is expected to result from serpentinization of mantle wedge peridotites by ascending, slab-derived fluids. According to the estimates of H2O loss from subducting slabs to the mantle wedge by van Keken et al.77 (3.3 × 108 Tg My−1), a serpentinization level of 20–50% for the forearc mantle wedge56, an antigorite density of 2,540 kg m−3, and the amount of H2 released by serpentinization from Reaction (5), it appears that wedge serpentinization produces enough H2 to convert all C transferred to the mantle wedge into CH4. In detail, full conversion of H2 produced by wedge serpentinization into CH4 would reach values up to 3.5–8.6 Mt per year, whereas only 2.5 Mt per year can be produced by converting all C transferred from subducting slabs to the mantle wedge (down to 2 GPa) into CH4.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Vitale Brovarone, A. et al. Massive production of abiotic methane during subduction evidenced in metamorphosed ophicarbonates from the Italian Alps. Nat. Commun. 8, 14134 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14134 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Proskurowski, G., Lilley, M. D. & Seewald, J. S. Abiogenic hydrocarbon production at Lost City hydrothermal field. Science 319, 604–607 (2008).

McCollom, T. M. Laboratory simulations of abiotic hydrocarbon formation in Earth’s deep subsurface. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 75, 467–494 (2013).

Etiope, G. & Sherwood Lollar, B. Abiotic methane on Earth. Rev. Geophys. 51, 276–299 (2013).

Schulte, M., Blake, D., Hoehler, T. & McCollom, T. M. Serpentinization and its implications for life on the early Earth and Mars. Astrobiology 60, 364–376 (2006).

Kelley, D. S. A serpentinite-hosted ecosystem: the lost city hydrothermal field. Science 307, 1428–1434 (2005).

Cannat, M., Fontaine, F. & Escartín, J. Serpentinization and associated hydrogen and methane fluxes at slow spreading ridges. Geophys. Monogr. Ser. 188, 241–264 (2010).

Scott, H. P., Hemley, R. J. & Mao, H. Generation of methane in the Earth’s mantle: in situ high pressure–temperature measurements of carbonate reduction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 14023–14026 (2004).

Kolesnikov, A., Kutcherov, V. G. & Goncharov, A. F. Methane-derived hydrocarbons produced under upper-mantle conditions. Nat. Geosci. 2, 566–570 (2009).

Huang, F. & Sverjensky, D. A. Aqueous acetate coexisting with immiscible fluid isobutane at subduction zone pressures. in Goldschmidt Conference Abstracts (2016).

Alt, J. C. et al. The role of serpentinites in cycling of carbon and sulfur: seafloor serpentinization and subduction metamorphism. Lithos 178, 40–54 (2013).

Kerrick, D. M. & Connolly, J. A. D. Subduction of ophicarbonates and recycling of CO2 and H2O. Geology 26, 375–378 (1998).

Lemoine, M., Boillot, P. & Tricart, G. Ultramafic and gabbroic ocean floor of the Ligurian Tethys (Alps, Corsica, Apennines). In search of a genetic model. Geology 15, 622–625 (1987).

Collins, N. C. et al. Subduction zone metamorphic pathway for deep carbon cycling: II. Evidence from HP/UHP metabasaltic rocks and ophicarbonates. Chem. Geol. 412, 132–150 (2015).

Pelletier, L. & Müntener, O. High-pressure metamorphism of the Lanzo peridotite and its oceanic cover, and some consequences for the Sesia–Lanzo zone (northwestern Italian Alps). Lithos 90, 111–130 (2006).

Debret, B., Nicollet, C., Andréani, M., Schwartz, S. & Godard, M. Three steps of serpentinization in an eclogitized oceanic serpentinization front (Lanzo Massif—Western Alps). J. Metamorph. Geol. 31, 165–186 (2012).

Groppo, C. & Compagnoni, R. Metamorphic veins from the serpentinites of the Piemonte Zone, western Alps, Italy: a review. Period. Mineral. 76, 95–124 (2007).

Castelli, D., Rolfo, F. & Rossetti, P. Petrology of ore-bearing rodingite veins from the Balangero asbestos mine (Western Alps): Studies on metamorphic rocks and minerals of the Western Alps A volume in memory of Ugo Pognante. Boll. Mus. Reg. Sci. Nat. Torino 13, 153–189 (1995).

Boudier, F. Structure and petrology of the Lanzo peridotite massif (Piedmont Alps). Geol. Soc. Am. Bull 89, 1574–1591 (1978).

Piccardo, G. B. The Lanzo peridotite massif, Italian Western Alps: Jurassic rifting of the Ligurian Tethys. Vol. 337, 47–69 (Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 2010).

Lagabrielle, Y., Fudral, S. & Kienast, J. La couverture océanique des ultrabasites de Lanzo (Alpes occidentales): arguments lithostratigraphiques et pétrologiques. Geodin. Acta 4, 43–55 (1990).

Beard, J. S. et al. Onset and progression of serpentinization and magnetite formation in olivine-rich troctolite from IODP Hole U1309D. J. Petrol. 50, 387–403 (2009).

Touret, J. Fluids in metamorphic rocks. Lithos 55, 1–25 (2001).

Roedder, E. Fluid Inclusions Vol. 12, Mineralogical Society of America (1984).

Bodnar, R. J. in Fluid Inclusions : Analysis and Interpretation, Short Course Series Vol. 32 (eds Samson, I., Anderson, A. & Marshall, D.) 1–8Mineral. Assoc., Canada (2003).

Hoefs, J. Stable Isotope Geochemistry Springer-Verlag (2009).

Cook-Kollars, J., Bebout, G. E., Collins, N. C. & Angiboust, S. Subduction zone metamorphic pathway for deep carbon cycling: I. Evidence from HP/UHP metasedimentary rocks, Italian Alps. Chem. Geol. 386, 31–48 (2014).

Piccoli, F. et al. Carbonation by fluid–rock interactions at high-pressure conditions: implications for carbon cycling in subduction zones. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 445, 146–159 (2016).

Galvez, M. E. et al. Graphite formation by carbonate reduction during subduction. Nat. Geosci. 6, 473–477 (2013).

McCollom, T. M. & Seewald, J. S. Carbon isotope composition of organic compounds produced by abiotic synthesis under hydrothermal conditions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 243, 74–84 (2006).

Cartwright, I. & Barnicoat, A. C. Stable isotope geochemistry of Alpine ophiolites: a window to ocean-floor hydrothermal alteration and constraints on fluid–rock interaction during high-pressure metamorphism. Int. J. Earth Sci. 88, 219–235 (1999).

Cartigny, P., Palot, M., Thomassot, E. & Harris, J. W. Diamond formation: a stable isotope perspective. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 42, 699–732 (2014).

Lazar, C., Zhang, C., Manning, C. E. & Mysen, B. O. Redox effects on calcite-portlandite-fluid equilibria at forearc conditions: carbon mobility, methanogenesis, and reduction melting of calcite. Am. Mineral. 99, 1604–1615 (2014).

Taran, Y. A., Kliger, G. A., Cienfuegos, E. & Shuykin, A. N. Carbon and hydrogen isotopic compositions of products of open-system catalytic hydrogenation of CO. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 6112–6125 (2010).

McCollom, T. M., Lollar, B. S., Lacrampe-Couloume, G. & Seewald, J. S. The influence of carbon source on abiotic organic synthesis and carbon isotope fractionation under hydrothermal conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 2717–2740 (2010).

Thomassot, E., Cartigny, P., Harris, J. & Viljoen, K. S. Methane-related diamond crystallization in the Earth’s mantle: stable isotope evidences from a single diamond-bearing xenolith. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 257, 362–371 (2007).

Simakov, S. K. et al. Nanodiamond finding in the hyblean shallow mantle xenoliths. Sci. Rep. 5, 10765 (2015).

Putnis, A. & Austrheim, H. in Metasomatism and the chemical transformation of rocks (eds Harlov, D. E. & Austrheim, H.) 141–170Springer, Lecture Notes in Earth System Sciences (2012).

Malvoisin, B. Mass transfer in the oceanic lithosphere: serpentinization is not isochemical. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 430, 75–80 (2015).

Connolly, J. A. D. Phase diagram methods for graphitic rocks and application to the system C−O−H−FeO−TiO2−SiO2 . Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 119, 94–116 (1995).

Holloway, J. R. Graphite-CH4-H2O-CO2 equilibria at low-grade metamorphic conditions. Geology 12, 455–458 (1984).

Malvoisin, B., Chopin, C., Brunet, F. & Galvez, M. E. Low-temperature wollastonite formed by carbonate reduction: a marker of serpentinite redox conditions. J. Petrol. 53, 159–176 (2011).

Galvez, M. E. et al. Metasomatism and graphite formation at a lithological interface in Malaspina (Alpine Corsica, France). Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 166, 1687–1708 (2013).

Sverjensky, D. A., Stagno, V. & Huang, F. Important role for organic carbon in subduction-zone fluids in the deep carbon cycle. Nat. Geosci. 7, 909–913 (2014).

Connolly, J. A. D. & Cesare, B. C‐O‐H‐S fluid composition and oxygen fugacity in graphitic metapelites. J. Metamorph. Geol. 11, 379–388 (1993).

Frost, B. R. On the stability of sulfides, oxides, and native metals in serpentinite. J. Petrol. 26, 31–63 (1985).

Masago, H., Omori, S. & Maruyama, S. Significance of retrograde hydration in collisional metamorphism: a case study of water infiltration in the Kokchetav ultrahigh-pressure metamorphic rocks, northern Kazakhstan. Gondwana Res. 18, 205–212 (2010).

Andersen, T. B. & Austrheim, H. Fossil earthquakes recorded by pseudotachylytes in mantle peridotite from the Alpine subduction complex of Corsica. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 242, 58–72 (2006).

Rubatto, D. & Hermann, J. Exhumation as fast as subduction? Geology 29, 3–6 (2001).

Hermann, J., Spandler, C., Hack, A. & Korsakov, A. Aqueous fluids and hydrous melts in high-pressure and ultra-high pressure rocks: implications for element transfer in subduction zones. Lithos 92, 399–417 (2006).

Ferrando, S., Frezzotti, M.-L., Orione, P., Conte, R. C. & Compagnoni, R. Late-Alpine rodingitization in the Bellecombe meta-ophiolites (Aosta Valley, Italian Western Alps): evidence from mineral assemblages and serpentinization-derived H2-bearing brine. Int. Geol. Rev. 52, 1220–1243 (2010).

Song, S., Su, L., Niu, Y., Lai, Y. & Zhang, L. CH4 inclusions in orogenic harzburgite: evidence for reduced slab fluids and implication for redox melting in mantle wedge. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 1737–1754 (2009).

Shi, G. U., Tropper, P., Cui, W., Tan, J. & Wang, C. Methane (CH4)-bearing fluid inclusions in the Myanmar jadeitite. Geochem. J. 39, 503–516 (2005).

Arai, S., Ishimaru, S. & Mizukami, T. Methane and propane micro-inclusions in olivine in titanoclinohumite-bearing dunites from the Sanbagawa high-P metamorphic belt, Japan: hydrocarbon activity in a subduction zone and Ti mobility. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 353, 1–11 (2012).

Ranero, C. R., Morgan, J. P., McIntosh, K. & Reichert, C. Bending-related faulting and mantle serpentinization at the Middle America trench. Nature 425, 367–373 (2003).

Faccenda, M. Water in the slab: A trilogy. Tectonophysics 614, 1–30 (2014).

Hyndman, R. D. & Peacock, S. M. Serpentinization of the forearc mantle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 212, 417–432 (2003).

Evans, B. W. Lizardite versus antigorite serpentinite: magnetite, hydrogen, and life(?). Geology 38, 879–882 (2010).

Sachan, H. K., Mukherjee, B. K. & Bodnar, R. J. Preservation of methane generated during serpentinization of upper mantle rocks: Evidence from fluid inclusions in the Nidar ophiolite, Indus Suture Zone, Ladakh (India). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 257, 47–59 (2007).

Kelemen, P. B. & Manning, C. E. Reevaluating carbon fluxes in subduction zones, what goes down, mostly comes up. PNAS 112, E3997–E4006 (2015).

Konn, C., Charlou, J. L., Holm, N. G. & Mousis, O. The production of methane, hydrogen, and organic compounds in ultramafic-hosted hydrothermal vents of the mid-atlantic ridge. Astrobiology 15, 381–399 (2015).

Ehlmann, B. L., Mustard, J. F. & Murchie, S. L. Geologic setting of serpentine deposits on Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, 1–5 (2010).

Ehlmann, B. L. et al. Subsurface water and clay mineral formation during the early history of Mars. Nature 479, 53–60 (2011).

Stagno, V., Ojwang, D. O., McCammon, C. A. & Frost, D. J. The oxidation state of the mantle and the extraction of carbon from Earth’s interior. Nature 493, 84–88 (2012).

Ménez, B., Pasini, V. & Brunelli, D. Life in the hydrated suboceanic mantle. Nat. Geosci. 5, 133–137 (2012).

Shilobreeva, S., Martinez, I., Busigny, V., Agrinier, P. & Laverne, C. Insights into C and H storage in the altered oceanic crust: results from ODP/IODP Hole 1256D. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 2237–2255 (2011).

Carbonin, S., Martin, S., Tumiati, S. & Rossetti, P. Magnetite from the Cogne serpentinites (Piemonte ophiolite nappe, Italy). Insights into seafloor fluid–rock interaction. Eur. J. Mineral. 27, 31–50 (2015).

Pasteris, J. D. Occurrence of graphite in serpentinized olivines in kimberlite. Geology 9, 356–359 (1981).

Connolly, J. A. D. The geodynamic equation of state: what and how. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 10, Q10014 (2009).

Holland, T. J. B. & Powell, R. An improved and extended internally consistent thermodynamic dataset for phases of petrological interest, involving a new equation of state for solids. J. Metamorph. Geol. 29, 333–383 (2011).

Vidal, O., Parra, T. & Trotet, F. A thermodynamic model for Fe-Mg aluminous chlorite using data from phase equilibrium experiments and natural pelitic assemblages in the 100 to 600°C, 1 to 25kb range. Am. J. Sci. 301, 557–592 (2001).

Vidal, O. et al. P-T-deformation-Fe3+/Fe2+ mapping at the thin section scale and comparison with XANES mapping: application to a garnet-bearing metapelite from the Sambagawa metamorphic belt (Japan). J. Metamorph. Geol. 24, 669–683 (2006).

Lanari, P., Wagner, T. & Vidal, O. A thermodynamic model for di-trioctahedral chlorite from experimental and natural data in the system MgO–FeO–Al2O3–SiO2–H2O: applications to P–T sections and geothermometry. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 167, 968 (2014).

McCollom, T. M. & Seewald, J. S. A reassessment of the potential for reduction of dissolved CO2 to hydrocarbons during serpentinization of olivine. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65, 3769–3778 (2001).

Bottinga, Y. Calculated fractionation factors for carbon and hydrogen isotope exchange in the system calcite-carbon dioxide-graphite-methane-hydrogen-water vapor. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 33, 49–64 (1969).

Ohmoto, H. & Rye, R. O. in Geochemistry of hydrothermal ore deposits (ed. Barnes, H. L.) 509–561John Whiley & Sons).

Clerc, C., Boulvais, P., Lagabrielle, Y. & de Saint Blanquat, M. Ophicalcites from the northern Pyrenean belt: a field, petrographic and stable isotope study. Int. J. Earth Sci. 103, 141–163 (2013).

van Keken, P. E., Hacker, B. R., Syracuse, E. M. & Abers, G. A. Subduction factory: 4. Depth-dependent flux of H2O from subducting slabs worldwide. J. Geophys. Res. 116, B01401 (2011).

Beyssac, O., Brunet, F., Petitet, J.-P., Goffé, B. & Rouzaud, J.-N. Experimental study of the microtextural and structural transformations of carbonaceous materials under pressure and temperature. Eur. J. Mineral. 15, 937–951 (2003).

Acknowledgements

Part of this research was financially supported by ATM-MNHN (project SERCH4 granted to A.V.B.). We thank O. Vidal, F. Brunet, C. Groppo, S. Ferrando, S. Tumiati, G. Etiope, P. Cartigny, F. Guyot, V. Milesi, B. Debret, J.A. Padrón-Navarta, M. Cannat, T. McCollom, D. Sverjensky, O. Beyssac, A. Shukla, A. Paradisi and E. Sterpetti, M. Fialin, N. Rividi, D. Troadec, A. Addad, D. Kilcoyne, F. Bourdelle, E. Lloret for discussion, technical help and access to analytical facilities. Part of this research was inspired by discussion with Marco Beltrando, who will be in our memories forever. The Focused Ion Beam (FIB) and Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) facility at IMPMC is supported by Région Ile de France grant SESAME 2006N°I-07-593/R, INSU-CNRS, INP-CNRS, University Pierre et Marie Curie—Paris 6, and by the French National Research Agency (ANR) grant no. ANR-07-BLAN-0124-01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.V.B. designed the project, collected and interpreted samples and data and wrote the paper. I.M. participated in the construction of the work and in the interpretation of stable isotope data and wrote the paper. A.E. participated in the construction of the work, acquisition of supporting STXM-XANES data not published in this paper and wrote the paper. R.C. participated in the fieldwork. C.C. provided assistance during stable isotope measurements and data analysis and wrote the paper. C.F. participated in the micro/nanoscale characterization of the samples. I.E. provided assistance during SEM and FIB analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Tables and Supplementary References. (PDF 2330 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Vitale Brovarone, A., Martinez, I., Elmaleh, A. et al. Massive production of abiotic methane during subduction evidenced in metamorphosed ophicarbonates from the Italian Alps. Nat Commun 8, 14134 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14134

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14134

This article is cited by

-

Methane-hydrogen-rich fluid migration may trigger seismic failure in subduction zones at forearc depths

Nature Communications (2024)

-

The rocky road to organics needs drying

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Early release of H2O during subduction of carbonated ultramafic lithologies

Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology (2023)

-

H2-H2O immiscibility in Earth’s upper mantle

Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology (2023)

-

Understanding planetary context to enable life detection on exoplanets and test the Copernican principle

Nature Astronomy (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.