Abstract

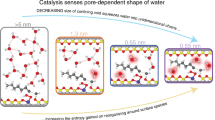

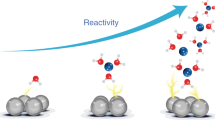

The dehydration of alcohols is involved in many organic conversions but has to overcome high free-energy barriers in water. Here we demonstrate that hydronium ions confined in the nanopores of zeolite HBEA catalyse aqueous phase dehydration of cyclohexanol at a rate significantly higher than hydronium ions in water. This rate enhancement is not related to a shift in mechanism; for both cases, the dehydration of cyclohexanol occurs via an E1 mechanism with the cleavage of Cβ–H bond being rate determining. The higher activity of hydronium ions in zeolites is caused by the enhanced association between the hydronium ion and the alcohol, as well as a higher intrinsic rate constant in the constrained environments compared with water. The higher rate constant is caused by a greater entropy of activation rather than a lower enthalpy of activation. These insights should allow us to understand and predict similar processes in confined spaces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite the seemingly ubiquitous use in organic conversion sequences, the dehydration of alcohols by hydronium ions in aqueous phase is surprisingly challenging, requiring reaction temperatures above 100 °C to occur at industrially acceptable rates1. The reasons for this lie in significant enthalpic and entropic barriers for the formation of carbocationic intermediates and for their decomposition to form the olefin and water. Enzymes, in contrast, are able to catalyse dehydration of alcohols with high rates at temperatures close to ambient2, which is attributed to the unique microenvironment of the catalytically active centers in the three-dimensional enzyme structures and the nearly concerted acid base interactions. In translating this concept to inorganic catalysts we have shown in recent preliminary experiments that zeolite pores are able to substantially increase the rate at which hydronium ions catalyse reactions3.

To delineate the thermodynamic and kinetic impact of the sub-nanometre-sized confines on the catalytic chemistry of hydronium ions, the kinetics and elementary steps of the dehydration of a secondary alcohol, cyclohexanol, in water and in pores of zeolite Beta (BEA) are explored. In-depth characterizations of this zeolite by extended X-ray absorption fine structure and 27Al magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy showed that in the presence of adsorbed water the charge-balancing protons form hydronium ions, H3O+(H2O)n, which reside locally near the zeolite Al3+ T-site bearing the charge-balancing protons in the absence of water4,5,6. Previous studies also provided infrared spectroscopic evidence for the formation of H-bonded and protonated polar molecules (for example, alcohol and water) at acid sites on HBEA and HZSM-5 zeolites7,8. More importantly, the principal reaction network of the zeolite BEA-catalysed dehydration established by in situ magic angle spinning 13C NMR spectroscopy9 in aqueous phase enables us to analyse in this contribution the role of the confines on the catalytic properties of hydronium ions.

Here, thermochemical and kinetic measurements are used in conjunction with density functional theory (DFT) and isotope labelling, to elucidate quantitatively the reaction pathway in the aqueous-phase dehydration of alcohols in constrained environment and analyse the benefits of such a sterically tailored environment based on transition state theory.

Results

H3PO4-catalysed aqueous-phase cyclohexanol dehydration

Dehydration of cyclohexanol catalysed by dilute hydronium ions (dissociated from H3PO4) leads solely to the formation of cyclohexene. Possible alkylation products, cyclohexyl cyclohexene and dicyclohexyl ether, were not observed. The absence of bimolecular reactions is concluded to be caused by the unfavourable conditions for bimolecular reactions at the low reactant concentrations. The low solubility of cyclohexene in the aqueous phase also disfavours bimolecular reactions with reactive intermediates such as cyclohexyloxonium and cyclohexyl cations.

The concentration of the hydronium ions, on proper corrections (Supplementary Table 1), has been used to calculate the turnover frequencies (TOFs) reported in Table 1 for the H3PO4-catalysed dehydration (Supplementary Fig. 1). The rate of the cyclohexanol dehydration was proportional to the concentration of hydronium ions, rather than the total H3PO4 concentrations, consistent with specific acid catalysis in the studied range of dilute H3PO4 concentrations (0.02–0.09 M; Supplementary Fig. 2). The turnover rate of cyclohexanol dehydration is roughly first order in alcohol at low concentrations (∼0.1–0.3 M), but deviates from first-order behaviour at higher concentrations (0.90 M; Supplementary Fig. 3). The measured activation barrier was ∼158 kJ mol−1 at two alcohol concentrations (0.32 and 0.90 M; see Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Zeolite-catalysed aqueous-phase cyclohexanol dehydration

The detailed physicochemical properties of zeolite HBEA150 (SiO2/Al2O3=150) are given in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Figs 5 and 6, and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). As with H3PO4, cyclohexene was the main product of cyclohexanol dehydration on zeolite HBEA in dilute aqueous solutions (0.32–1.1 M). The nearly 100% selectivity to cyclohexene at short reaction times (for example, <1 h at 200 °C) indicates that water elimination proceeds preferentially via an intramolecular rather than an intermolecular pathway. In contrast to H3PO4, HBEA catalysed also ether formation and C–C alkylation reactions at higher conversions9, suggesting that the large intracrystalline voids of zeolite BEA allow bimolecular reactions10.

The rates and TOFs for the dehydration of cyclohexanol on HBEA (Supplementary Fig. 7) are also reported in Table 1. The dehydration TOFs on HBEA were an order of magnitude higher than those catalysed by aqueous-phase hydronium ions at 0.32 M alcohol concentration (Table 1). It is noteworthy that TOFs were obtained by normalizing the rates to the concentration of total Brønsted acidic sites (BAS) in HBEA150 (Supplementary Table 2), as we have shown earlier that all the BAS are present in the form of solvated hydronium ions4, which are equally active in aqueous-phase dehydration11. Surprisingly, the activation energies (162–164 kJ mol−1, see Supplementary Fig. 8) measured on HBEA in aqueous phase were similar to those (158 kJ mol−1) measured in aqueous H3PO4. However, the rate was zero-order in cyclohexanol (measured: 0.1±0.1; see Supplementary Fig. 9), much lower than the first-order dependence observed in H3PO4 solution. The zero-order kinetics for cyclohexanol suggests that nearly all hydronium ions are interacting with the alcohol or maintain—at least—a fully occupied precursor state to the alcohol-hydronium ion complex. Another interesting observation is that the dehydration of cyclohexanol catalysed by a mixture of H3PO4 (0.02 M) and HBEA150 (140 mg) showed a significantly higher reaction rate than the sum of the individual rates on each acid (Supplementary Table 4).

Adsorption of cyclohexanol on zeolite HBEA

The adsorption isotherm of cyclohexanol and the associated heats of adsorption are shown in Fig. 1. Microgravimetric analyses of gas-phase cyclohexanol adsorption on the zeolite provide an estimate of the maximum alcohol uptake in the absence of water (see Supplementary Fig. 10).

Langmuir-type isotherms satisfactorily describe the uptake of cyclohexanol from both gas (without water) and aqueous phase on zeolite HBEA150. The saturation uptakes of cyclohexanol and water (Supplementary Table 5) correspond to eight cyclohexanol and ten water molecules per unit cell at the saturation limit (room temperature). In good agreement, a maximum of 8 cyclohexanol molecules or 20–30 water molecules in 1 unit cell are allowable at the highest pore filling degree, according to DFT calculations.

Adsorption equilibrium constants (Kads) for cyclohexanol uptake along with the measured enthalpies and entropies were determined (Supplementary Table 6). The molar adsorption enthalpy of cyclohexanol adsorbed from aqueous phase is −22 kJ mol−1 (Fig. 1). This enthalpy is the result of transferring cyclohexanol from the aqueous medium (breaking H-bonding between cyclohexanol and water) and the displacement of water by cyclohexanol in the zeolite pores, the magnitude depending on the strengths of interactions between cyclohexanol/water and the pores, as well as the BAS.

With increasing temperatures (7–80 °C), saturation uptakes decreased from 1.75 to 1.31 mmol gHBEA−1 (Supplementary Table 5). This decrease is caused by the density change of the adsorbed phase in the micropore with temperature12. By extrapolating saturation uptakes to 160–200 °C, it is estimated that ∼5 cyclohexanol molecules are present per unit cell at saturation limit under reaction conditions (see Supplementary Note 1). Assuming that the remaining micropore volume is filled by water, the concentration of water molecules in the pore would increase to ∼20 per unit cell at reaction temperatures. It is noteworthy that the initial alcohol-to-water ratio in the zeolite pore is, thus, a factor of 50 higher than in solution (for example, 5.3–5.6 × 10−3 for 0.32 M solution at 160–200 °C). Extrapolation of Kads to reaction temperatures suggests that Kads decreased from 20 to 12 as the reaction temperature increased from 160 to 200 °C. This suggests an almost complete pore filling under reaction conditions, in line with the zero-order kinetic regime for the main dehydration pathway.

Mechanism of dehydration of cyclohexanol in aqueous phase

Having established the principal kinetic features of the elimination of water from cyclohexanol catalysed by hydronium ions, we use the H/D kinetic isotope effect (KIE) and 18O-tracer experiments, to investigate whether the elimination occurs via an E1 or E2 mechanism.

The TOFs for dehydration using C6H11OH and C6D11OD (forming C6D11OH on exchange with H2O) are shown in Table 2. H/D KIEs of ∼3 were observed for olefin formation catalysed by hydronium ions in open water and in the nanopores of HBEA. A KIE of such a magnitude indicates that C–H(D) bond cleavage is involved in the kinetically relevant step (that is, its rate constant appears in the kinetic expression). The primary KIE is inconsistent with the formation of the carbocation or the C–O bond cleavage being rate determining. Both steps would have secondary KIEs for rehybridization of α-C from sp3 to sp2, estimated to be <1.3 at 150–190 °C. In turn, this indicates that either an E1 mechanism with a kinetically relevant C–H bond cleavage or an E2 mechanism in which the C–O and the C–H bonds are cleaved in a concerted step is in agreement with the observed KIE.

To discriminate between the two mechanistic possibilities, 18O-labelled water was used as the solvent (Table 3). The reverse rate at 20% conversion, that is, the hydration of cyclohexene, would lead to ∼2% 18O incorporation, based on the analysis of the effective equilibrium constant (Supplementary Table 7) obtained by fitting the derived rate expression (details shown in Supplementary Note 2) to the in situ time-resolved infrared data collected during cyclohexanol dehydration (Supplementary Fig. 11). As olefin hydration hardly occurred under the applied conditions on HBEA and H3PO4, the E2-like pathways alone, with concerted C–O and C–H bond scissions, cannot explain the significant 18O incorporation (9–17%) into cyclohexanol. With the SN2 path for oxygen exchange between water and secondary/tertiary alcohols also ruled out13,14,15,16, the only possible pathway for this level of 18O incorporation would be recombination between 18O water and an intermediate, which is formed on C–O bond cleavage and which precedes the Cβ–H bond cleavage TS. This, in turn, makes the E1-type path the dominating mechanism for dehydration of cyclohexanol, regardless of whether the hydronium ion exists in homogeneous solution or localized in a pore.

DFT calculations of hydronium ion catalysed pathways in HBEA

The DFT calculations only address the kinetically relevant intermediates for protonation and H2O elimination. Other steps, such as desorption of water and olefins, will be discussed elsewhere, because they are irrelevant for the rates of dehydration. The calculated energy profiles for the reaction at 170 °C are shown in Fig. 2. The BEA unit cell may contain three to ten H2O molecules in proximity to the hydronium ion. For the theoretical evaluation of the interaction of the alcohol with the hydronium ion, we chose an example hydronium ion cluster with a H3O+(H2O)7 structure, the presence of which was identified by ab initio molecular dynamics simulations (a total of 26 water molecules in the unit cell; see Supplementary Fig. 12). This structure includes extended hydration shells beyond the first shell.

The energy diagram is shown for the aqueous-phase dehydration of cyclohexanol over a periodic HBEA (Al4H4Si60O128) model. The active site in zeolite equilibrated with aqueous phase is modelled by H3O+(H2O)7, with the configurations and energies optimized. All species, except for those denoted with (g), are in the unit cell. The detailed structures and configurations of the adsorbed intermediates, transition states and the H3O+(H2O)7 hydronium ion cluster are shown in the Supplementary Fig. 13. Enthalpy and free energy values (at 170 °C) are shown outside and inside the brackets, respectively.

Up to four cyclohexanol molecules were considered in addition to the hydronium ion in one BEA unit cell. The alcohol is seen to interact with the hydronium ion, forming an H-bond, while also interacting with the pore walls. The calculated enthalpy and free energy for cyclohexanol (gas) adsorption and subsequent interaction with the zeolitic hydronium ion (A, Fig. 2) were −108 and −50 kJ mol−1, respectively. These values are in reasonable agreement with gas phase adsorption and calorimetric measurements (Supplementary Fig. 10). The H-bonded cyclohexanol is protonated and forms an alkoxonium ion (B, Fig. 2). The activation barrier for this step is 69 kJ mol−1 (from A to TS1, Fig. 2). This protonation step is endothermic (ΔH°=+ 36 kJ mol−1) and endergonic (ΔG°=+55 kJ mol−1). Thus, the protonated alcohol is expected to be a minority species at typical reaction temperatures.

For comparison DFT calculations were performed for both E1- and E2-type elimination paths. On the E1-type path, the C–O bond cleavage has an activation barrier of 95 kJ mol−1, with an entropy gain of 34 J mol−1 K−1. In TS2, the leaving OH2 is almost neutral and the positive charge remains largely on the [C6H11] moiety. Next, the C6H11+ carbenium ion deprotonates to the hydronium ion cluster forming cyclohexene. In TS3, a H2O molecule nearby acts as the base to abstract the β-H; the Cβ–H bond is almost fully broken (2.46 Å; see Supplementary Fig. 13). This deprotonation has a small barrier (43 kJ mol−1) in the forward direction and a higher barrier (92 kJ mol−1) in the reverse direction. The higher free-energy barrier for deprotonation (from C to TS3) than for C–O bond recombination (from C to TS2) is in line with the kinetic relevance of C–H bond cleavage concluded from the measured primary H/D isotope effects.

In comparison, on the E2-type path, the enthalpy of activation and entropy of activation calculated at 170 °C were 137 kJ mol−1 and 74 J mol−1 K−1, respectively (from B to TS4). These activation energies and entropies are larger than the corresponding values for the E1-type path (Fig. 2), making the latter also more plausible from the point of DFT modeling.

Causes for the rate increase by pore constraint

Let us analyse in the next step the reasons for the markedly higher (for example, ∼16 times at 180 °C and 0.32 M cyclohexanol) rates catalysed by hydronium ions present in the pore of zeolite BEA compared with that in open water.

For brevity, in aqueous H3PO4, we represent the hydrated hydronium ion as an Eigen-type17,18 structure, H3O+(H2O)3(aq), in which only the numbers of first-shell waters are shown. Without steric constraints, the reaction starts with the association of the hydronium ion with cyclohexanol, presumably replacing a H2O molecule by cyclohexanol in the first solvation shell of the hydronium ion19 (equation (1)).

Under reaction conditions, this step is quasi-equilibrated, with an association constant KL,a (where the subscript ‘L’ stands for the liquid phase and ‘a’ stands for association).

The steps following the association of the proton with the alcohol are all unimolecular, as we demonstrate later. Together, they can be written as equation (2), with a collective forward rate constant kL,d (where ‘d’ stands for dehydration)

where R(−H) represents the olefin product (cyclohexene) having one less hydrogen than the alkyl group R (cyclohexyl).

The rate of dehydration normalized to the concentration of total hydronium ions [H3O+]0 ([H3O+]0=[H3O+(H2O)3]+[H3O+(H2O)2ROH]) is TOF (Table 1) and defined as the product of the rate constant kL,d and the fraction of hydronium ions associated with the alcohol, θL,a. (equations (3) and (4); details of derivation and calculation shown in Supplementary Note 3 and 4)

The association constant KL,a was derived from initial reaction rates, r, measured at two different alcohol concentrations (0.32 and 0.90 M). The values of KL,a, the alcohol-hydronium ion association equilibrium constant, decreased modestly from 40 to 37 with increasing temperature from 160 to 200 °C (Supplementary Table 8). A similar weak temperature dependence had been reported for the protonation of C2–C4 aliphatic alcohols by aqueous sulfuric acids (exothermicity of −2 kJ mol−1)20. At 0.32 M and 160–200 °C, the fraction of hydronium ions associated with cyclohexanol (θL,a) was ∼0.17 (Supplementary Table 8). With the regressed KL,a and kL,d, the changes in enthalpy and entropy for association equilibrium between hydronium ion and cyclohexanol in H3PO4, as well as the intrinsic activation barriers for H3PO4-catalysed dehydration were determined (Supplementary Figs 14 and 15).

In analogy to the plain aqueous-phase dehydration, the rate normalized to the hydronium ion concentration in zeolite HBEA (TOF) is

θz,a is the fractional coverage or association of the hydronium ions with cyclohexanol. In zeolite HBEA, ∼5 cyclohexanol and ∼20 water molecules occupy a unit cell, whereas in a 0.32 M solution, 1 cyclohexanol molecule shares the volume with 180 water molecules. Consequently, θz,a has a value at least close to 1, in comparison with a θL,a value of 0.17 in a solution containing 0.02 M H3PO4 and 0.32 M cyclohexanol. In turn, the rate constant in zeolite HBEA (kz,d) is at least ∼2.7 times higher than that in the homogeneous acid solution (kL,d) (see Supplementary Note 5). Altogether, the analysis shows that the HBEA pore provides an environment that not only increases the fraction of hydronium ions associated with alcohol, but also increases the intrinsic dehydration rate constant, collectively contributing to more than one order of magnitude enhancement in rate compared to the homogeneously catalysed dehydration (Table 1).

Interestingly, the observed rates with a mixture of H3PO4 and HBEA were higher than the sum of rates obtained with the individual acids (Supplementary Table 4), presumably due to phosphoric acid being adsorbed in the pore21,22. We speculate that additional hydronium ions generated by dissociation of phosphoric acid in the pore partly account for this rate enhancement, whereas alternative elimination pathways (for example, cyclohexyl phosphate ester mediated23) may be available in the unique confines of the zeolite (see extended discussion in the Supplementary Note 6). However, the concentration of H3PO4 and the extent of its dissociation in the zeolite pore at reaction temperature are presently not known, preventing a quantitative analysis of the potential causes.

Discussion

In the catalytic sequence of the zeolite-catalysed dehydration, cyclohexanol is first adsorbed from aqueous solution into intracrystalline voids. From aqueous phase, this step is accompanied with a change of −22 kJ mol−1 in enthalpy and −25 J mol−1 K−1 in entropy (Supplementary Table 6). In the presence of water, the zeolite BAS form confined hydronium ions4,5,6,7,8. The hydronium ion protonates the alcohol, to which it is H-bonded. DFT calculations suggest that the alcohol protonation equilibrium constant in zeolites depends critically on the number of water molecules in the hydronium-ion cluster (Supplementary Table 9). Although water has a smaller proton affinity than cyclohexanol, a cluster of water molecules (n≥3) may have a higher proton affinity than cyclohexanol. As a consequence, proton transfer from a hydronium ion-water cluster to cyclohexanol will become progressively more favourable as the cluster decreases in size. In aqueous solution, the prevalent hydronium ion in zeolite HBEA was simulated as H3O+(H2O)7. With this cluster, protonation of cyclohexanol is thermodynamically unfavourable (DFT: ΔG°=+55 kJ mol−1). Accordingly, a majority of the BAS interacts with the alcohol without a significant extent of proton transfer. In turn, the measured enthalpy of activation (159 kJ mol−1) and corresponding entropy change (87 J mol−1 K−1) reflect the difference between the kinetically relevant TS (that is, Cβ–H bond cleavage TS) and the H-bonded alcohol state (A in Fig. 2).

Because of the weak temperature dependence of KL,a and [ROH]aq/[H2O]l ratio (equation (3)), the intrinsic activation barrier (Table 4) is anticipated to be close to the measured energy of activation (Table 1). As discussed, the intrinsic rate constants for H3PO4-catalysed dehydration were determined at 160–200 °C, yielding the activation enthalpy (157 kJ mol−1) and the activation entropy (73 J mol−1 K−1). Thus, the dehydration of aqueous cyclohexanol occurs in HBEA with a similar activation enthalpy, yet a greater entropy gain than in aqueous acidic solution (Table 4).

Thus, cyclohexanol dehydration was catalysed with markedly higher rates when the hydronium ions were confined in zeolite pores. This rate enhancement is partly explained by the intrinsic rate constant for dehydration, which was at least two to three times higher in HBEA than in water. It is noteworthy that the intrinsic enthalpies of activation were similar for catalysis in BEA pores as in water, whereas the associated entropy of activation was greater for hydronium ion catalysis in the zeolite pores than in water. The largest effect arising from a constrained environment is, however, related to the higher association extent of cyclohexanol with the hydronium ion. We attribute this to the lower entropy loss when forming an association complex in the zeolite pore. In contrast to plain aqueous phase, the lower entropy of molecules mobile in pores of molecular sieves will lead to a much smaller loss in forming the reactant-catalyst adduct. Such enhanced association between substrate and active site, as well as the entropically favoured intrinsic kinetics within sterically constrained environments bears a strong resemblance to enzyme catalysis24,25. This work suggests a new approach to designing reaction environments that could lead to enzyme-like activities and selectivities.

Methods

Zeolite catalysts

Zeolite HBEA150 (SiO2/Al2O3=150) was obtained from Clariant in H-form. HBEA150 was calcined at 500 °C in a 100 ml min−1 flow of dry air for 6 h before the reaction. Detailed descriptions of characterization methods are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Liquid-phase adsorption and calorimetry

Heat of adsorption, that is, uptake of cyclohexanol (Sigma-Aldrich, 99%) from aqueous solutions into zeolite HBEA150, was determined by liquid calorimetry using a Setaram Calvet C80 calorimeter. Reversal mixing cells were used, to separate the adsorptive from the adsorbent. The lower compartment was loaded with 0.03 g zeolite (m) immersed in 0.8 ml water. The upper compartment was loaded with 0.2 ml of the desired cyclohexanol solution resulting in a total volume (V) of 1 ml with a concentration c0. Reference cell is loaded with identical compositions, without zeolite. Uptake (q) was determined using liquid NMR and quantification was accomplished adding an internal standard (1,3,5-trioxane; Sigma-Aldrich, ≥99%) to the solution at equilibrium (ce), assuming q=V(c0−ce)m−1. Adsorption isotherms were obtained immersing 100, 50 or 20 mg of zeolite in a cyclohexanol solution of a defined concentration for at least 24 h. The solution was separated from the zeolite and the residual concentration was determined via liquid NMR using the internal standard, trioxane.

Kinetic measurements

Kinetic measurements were performed at 160–200 °C using a 300 ml Hastelloy PARR reactor. An example of a typical reaction in aqueous phase: 3.3 g cyclohexanol and 100 ml 0.02 M aqueous H3PO4 (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥99.999% trace metals basis) solution or 140 mg HBEA and 80 ml 0.32 M aqueous cyclohexanol solution are sealed in the reactor. In all cases, the reactor is then pressurized with 50 bar H2 at room temperature and heated up while stirred vigorously (∼700 r.p.m.). Rates do not vary with the stirring speed that is >400 r.p.m. (Supplementary Fig. 16). The reaction time is reported counting from the point when the set temperature is reached (12–15 min). On completion, the reactor is cooled using an ice/water mixture. As olefin is formed, which is segregated as another liquid phase, the contents are extracted using dichloromethane (Sigma-Aldrich, HPLC grade; 25 ml per extraction, 4 times) or ethyl acetate. It is important that the extraction work-up be completed in a short period of time (20 min), to minimize the loss of the volatile olefin phase; this way, the carbon balance could be maintained typically better than 85% and even better than 95% in favourable cases. The organic phase after being dried over sodium sulfate (Acros Organics, 99%, anhydrous) is analysed on an Agilent 7890A GC equipped with a HP-5MS 25 m × 0.25 μm (i.d.) column, coupled with Agilent 5975C MS. Then, 1,3-dimethoxybenzene (Sigma-Aldrich, 99%) was used as the internal standard for quantification.

H/D KIEs and 18O tracer experiments

Rates of dehydration of perdeuterated cyclohexanol (0.10–0.11 M; present as C6D11OH in water) were measured in the Parr reactor, using protocols identical to those described for standard reactions using non-labelled alcohol (see above).

Experiments using 18O-labelled water and non-labelled cyclohexanol (0.3 M) were carried out in a ∼2 ml stirred batch reactor constructed from a stainless steel ‘tee’ (HiP), whereas ensuring similar solution-to-headspace ratios (0.3–0.4) as in the Parr reactor. The mixture after reaction was extracted with dichloromethane (0.5 ml per extraction, 4 times), dried over Na2SO4 and analysed with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. The intensity ratio between two O-containing fragment ions (m/e=57 and 59) can be used to quantify the extent of 18O incorporation into cyclohexanol (the ratio between the single ion areas for m/e=59 and m/e=57 is 0.01 for unlabelled alcohol).

DFT calculations

All DFT calculations employed a mixed Gaussian and plane wave basis sets and were performed using the CP2K code26. The basis set superimposition error derived from Gaussian localized basis set used in our CP2K calculations has been estimated to be ∼3 kJ mol−1 (ref. 27). The core electrons were represented by norm-conserving Goedecker–Teter–Hutter pseudo-potentials28,29,30 and the valence electron wave function was expanded in a double-zeta basis set with polarization functions31 along with an auxiliary plane wave basis set with an energy cutoff of 360 eV. In all calculations we used the generalized gradient approximation exchange-correlation functional of Perdew, Burke and Enzerhof32. All configurations were optimized using the Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno algorithm with self-consistent field (SCF) convergence criteria of 10−8 a.u. To compensate the long-range van der Waals interaction between adsorbate molecules and the zeolite, we employed the DFT-D3 scheme33 with an empirical damped potential term added into the energies obtained from exchange-correlation functional. A periodic three-dimensional all siliceous BEA structure of Si64O128 with experimental lattice parameters of 12.6614 × 12.6614 × 26.4061 Å3 was used in this work34. The unit cell of the HBEA with Si/Al=15 ratio then was built by simply replacing four T-site (T3, T4, T5 and T9) Si atoms with four Al atoms. This resulting negative charges were compensated by adding four H atoms at the oxygen atoms, which are close neighbours of Al atoms on the zeolite frame, yielding the active BAS, that is, Si-O(H)-Al-O of the HBEA zeolite.

The adsorption energy of cyclohexanol into the pore of HBEA zeolite is calculated as follows:

where  is the total energy of cyclohexanol adsorbed in the pore of HBEA, EHBEA is the total energy of the HBEA, and

is the total energy of cyclohexanol adsorbed in the pore of HBEA, EHBEA is the total energy of the HBEA, and  is the total energy of cyclohexanol in vacuum.

is the total energy of cyclohexanol in vacuum.

The Gibbs free energy changes (ΔG°) along different reaction pathways were calculated using statistical thermodynamics35. To account for important entropic contribution, the method for calculating the vibrational entropic term, employed by De Moor et al.36, was used in this work.

Data availability

All data are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files, and from the authors upon reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Liu, Y. et al. Enhancing the catalytic activity of hydronium ions through constrained environments. Nat. Commun. 8, 14113 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14113 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Zhao, C. & Lercher, J. A. Upgrading pyrolysis oil over Ni/HZSM-5 by cascade reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 5935–5940 (2012).

Marlière, P. Method for producing an alkene comprising step of converting an alcohol by an enzymatic dehydration step. EP Patent 2,336,340 (2011).

Zhao, C. & Lercher, J. A. Selective hydrodeoxygenation of lignin-derived phenolic monomers and dimers to cycloalkanes on Pd/C and HZSM-5 catalysts. ChemCatChem 4, 64–68 (2011).

Vjunov, A. et al. Quantitatively probing the Al distribution in zeolites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8296–8306 (2014).

Corma, A. et al. Synthesis and structure of polymorph B of zeolite beta. Chem. Mater. 20, 3218–3223 (2008).

Vjunov, A. et al. Impact of aqueous medium on zeolite framework integrity. Chem. Mater. 27, 3533–3545 (2015).

Pazé, C. et al. Acidic properties of H-β zeolite as probed by bases with proton affinity in the 118–204 kcal mol−1 range: a FTIR investigation. J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 4740–4751 (1997).

Bordiga, S. et al. Probing zeolites by vibrational spectroscopies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 7262–7341 (2015).

Vjunov, A. et al. Following solid-acid-catalyzed reactions by MAS NMR spectroscopy in liquid phase-zeolite-catalyzed conversion of cyclohexanol in water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 479–482 (2013).

Chiang, H. & Bhan, A. Catalytic consequences of hydroxyl group location on the rate and mechanism of parallel dehydration reactions of ethanol over acidic zeolites. J. Catal. 271, 251–261 (2010).

Vjunov, A., Derewinski, M. A., Fulton, J. L., Camaioni, D. M. & Lercher, J. A. Impact of zeolite aging in hot liquid water on activity for acid-catalyzed dehydration of alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 10374–10382 (2015).

Do, D. D. in Adsorption Analysis: Equilibria and Kinetics Vol. 2, 149–190 (Imperial College Press, 1998).

Bunton, C. A., Konasiewicz, A. & Llewellyn, D. R. Oxygen exchange and the walden inversion in sec.-butyl alcohol. J. Chem. Soc. (Resumed) 604–607 (1955).

Bunton, C. A. & Llewellyn, D. R. 676. Tracer studies on alcohols. Part II. The exchange of oxygen-18 between sec.-butyl alcohol and water. J. Chem. Soc. (Resumed) 3402–3407 (1957).

Merritt, M. V. et al. Oxygen exchange as a function of racemization in 1-phenyl-1-ethanol. Kinetic evidence for ion-dipole pair intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 3560–3566 (1990).

Merritt, M. V. et al. Enantiomer-specific oxygen exchange reactions. 2. Acid-catalyzed water exchange with 1-phenyl-1-alkanols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 5551–5559 (1994).

Eigen, M. Proton transfer, acid-base catalysis, and enzymatic hydrolysis. Part I: elementary processes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 3, 1–19 (1964).

Markovitch, O. & Agmon, N. Structure and energetics of the hydronium hydration shells. J. Phys. Chem. A 111, 2253–2256 (2007).

Wells, C. F. Association of protons with oxygen-containing molecules in aqueous solutions. Part 1. The protonation of methanol and isopropanol in varying conditions. Trans. Faraday Soc. 61, 2194 (1965).

Michelsen, R. R. et al. Protonation of Alcohols in Sulfuric Acid Solutions at UT/LS Conditions. Eos Trans. AGU 88, abstr. A21E-0798 (2007).

van der Bij, H. E. & Weckhuysen, B. M. Phosphorus promotion and poisoning in zeolite-based materials: synthesis, characterisation and catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 7406–7428 (2015).

Uzunova, E. L. & Mikosch, H. Adsorption of phosphates and phosphoric acid in zeolite clinoptilolite: electronic structure study. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 232, 119–125 (2016).

Roberts, J. D. & Caserio, M. C. in Basic Principles of Organic Chemistry 2nd edn, 634 (W. A. Benjamin, Inc., 1977).

Bruice, T. C. & Lightstone, F. C. Ground state and transition state contributions to the rates of intramolecular and enzymatic reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 32, 127–136 (1999).

Fischer, M. et al. Enzyme catalysis via control of activation entropy: site-directed mutagenesis of 6,7-dimethyl-8-ribityllumazine synthase. J. Mol. Biol. 326, 783–793 (2003).

Bandow, S. et al. Electronic and vibrational properties of Rb-intercalated MoS2 nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 204, 222–226 (1995).

VandeVondele, J. & Hutter, J. R. Gaussian basis sets for accurate calculations on molecular systems in gas and condensed phases. J. Chem. Phys. 127, 114105 (2007).

Goedecker, S., Teter, M. & Hutter, J. Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 54, 1703–1710 (1996).

Hartwigsen, C., Goedecker, S. & Hutter, J. Relativistic separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials from H to Rn. Phys. Rev. B 58, 3641–3662 (1998).

Krack, M. Pseudopotentials for H to Kr optimized for gradient-corrected exchange-correlation functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 114, 145–152 (2005).

Van Houteghem, M. et al. Analysis of the basis set superposition error in molecular dynamics of hydrogen-bonded liquids: application to methanol. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 104506 (2012).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Newsam, J. M., Treacy, M. M. J., Koetsier, W. T. & Gruyter, C. B. D. Structural characterization of zeolite beta. Proc. R. Soc. A 420, 375–405 (1988).

Psofogiannakis, G., St-Amant, A. & Ternan, M. Methane oxidation mechanism on Pt(111): a cluster model DFT study. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 24593–24605 (2006).

De Moor, B. A. et al. Normal mode analysis in zeolites: toward an efficient calculation of adsorption entropies. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 7, 1090–1101 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Jianzhi Hu for assistance with the 27Al MAS NMR measurements and Mr Sebastian Prodinger for independent checks on the aqueous-phase adsorption isotherms. This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences. Portions of the NMR experiments were performed at the William R. Environmental Molecular Science Laboratory (EMSL), a national scientific user facility sponsored by the DOE’s Office of Biological and Environmental Research located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL). Portions of the computational work were performed using resources provided by EMSL and by the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC). PNNL is a multi-programme national laboratory operated for DOE by Battelle Memorial Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L., A.V. and H.S. carried out the kinetic experiments. Y.L. and A.V. performed the characterizations. H.S. and S.E. performed the calorimetric and adsorption measurements. D.M. performed the DFT calculations. Y.L., H.S. and D.M.C. analysed the kinetic data. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary figures, supplementary tables, supplementary notes, supplementary methods and supplementary references. (PDF 1769 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Vjunov, A., Shi, H. et al. Enhancing the catalytic activity of hydronium ions through constrained environments. Nat Commun 8, 14113 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14113

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14113

This article is cited by

-

The concept of active site in heterogeneous catalysis

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2022)

-

Rational Design of Mixed Solvent Systems for Acid-Catalyzed Biomass Conversion Processes Using a Combined Experimental, Molecular Dynamics and Machine Learning Approach

Topics in Catalysis (2020)

-

Solvent-determined mechanistic pathways in zeolite-H-BEA-catalysed phenol alkylation

Nature Catalysis (2018)

-

Tailoring nanoscopic confines to maximize catalytic activity of hydronium ions

Nature Communications (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.