Abstract

Cross-coupling is a fundamental reaction in the synthesis of functional molecules, and has been widely applied, for example, to phenols, anilines, alcohols, amines and their derivatives. Here we report the Ni-catalysed Stille cross-coupling reaction of quaternary ammonium salts via C–N bond cleavage. Aryl/alkyl-trimethylammonium salts [Ar/R–NMe3]+ react smoothly with arylstannanes in 1:1 molar ratio in the presence of a catalytic amount of commercially available Ni(cod)2 and imidazole ligand together with 3.0 equivalents of CsF, affording the corresponding biaryl with broad functional group compatibility. The reaction pathway, including C–N bond cleavage step, is proposed based on the experimental and computational findings, as well as isolation and single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis of Ni-containing intermediates. This reaction should be widely applicable for transformation of amines/quaternary ammonium salts into multi-aromatics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Pd-catalysed Stille cross-coupling reaction between stannanes and organic halides (RX) was discovered during 1976–1978 (refs 1, 2, 3), and is currently the second most widely used cross-coupling method for the synthesis of functional molecules and polymers, both in laboratory research and in industry4,5,6,7,8,9,10. However, Stille coupling using C–O11,12,13,14 and C–N15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 electrophiles, such as phenol and amine derivatives, has hardly been investigated23,24,25, even though such compounds are frequently encountered in synthetic investigations.

Amine groups occur widely in natural products, and are also found in many pharmaceuticals, dyes and functional molecules. A large variety of amines are commercially available, mostly at reasonable cost. On the other hand, transformation of the NR2 group is generally difficult, due to the chemical inertness of the C−N bond. Therefore, efficient C−N bond conversion methods suitable for late-stage functionalization would greatly expand the utility of amine compounds as synthetic feedstocks. Quaternary organo-ammonium salts can be easily prepared from various aryl/alkyl amines. Their potential usage in cross-coupling was pioneered by Wenkert et al.26 (Ni-catalyst and Grignard reagent). Other protocols have been developed by MacMillan27 (Ni-catalyst and arylboron reagent), Wang28 (Ni-catalyst and organozinc reagent), Watson29 (Ni-catalyst and aryl/alkylboron reagent) and others30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37, and it is well established that quaternary organo-ammonium salts show diverse reactivity and synthetic utility as efficient substitutes for halides. However, the Stille reaction via C–N bond cleavage in such substrates has remained a missing piece in cross-coupling chemistry.

Herein, we describe the first Ni-catalysed Stille coupling reaction of C–N electrophiles (quaternary organo-ammonium salts). Although Ni catalysts are generally much less expensive than the corresponding Pd catalysts, they have been rarely used for Stille coupling23. We show that the reaction mediated by commercially available Ni-catalyst/imidazole ligand and CsF provides high synthetic efficiency and broad functional group compatibility.

Results

Ni-catalysed couplings of ammonium salts and stannanes

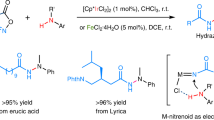

Aryltrimethylammonium salts 1 were readily synthesized from various anilines/amines bearing NH2, NHMe or NMe2 groups (Fig. 1). We started to examine the reaction of 1 with aryltrimethylstannane 2, which can be readily obtained by utilizing our recently developed naphthalene-catalysed quantitative synthesis of stannyl lithium38, or by employing functionalized Grignard reagents or other organometallics39. After the extensive experimentation (Supplementary Tables 1–3), we identified the optimum conditions as heating a mixture of 1 (as triflate) and 2 in 1:1 ratio in dioxane with CsF as base, Ni(cod)2 as catalyst and 1,3-dicyclohexylimidazol-2-ylidene (ICy) as ligand. We next examined the scope of the reaction for various ammonium salts 1, with 2a as a representative stannane. The results are summarized in Table 1.

We found that (1) tolyltrimethylammonium triflates were converted very smoothly and selectively to the corresponding coupling products, and the location (ortho-, meta- or para-) of the methyl substituent did not greatly affect the reaction (3aa-ca), though a highly sterically demanding substrate slowed down the reaction (3da); (2) substrates bearing electron-donating groups are less reactive (3aa-ea), while those with electron-withdrawing groups, including polar functional groups such as fluorine (3fa-ga), ester (3ha), ketone (3ia), nitrile (3ja), silyl (3ka) and sulfone (3la), which are generally sensitive to bases and organometallics, showed excellent reactivity; (3) other aromatic substrates such as biphenyl or naphthalene also reacted efficiently (3ma-na), indicating that molecules with expanded π-conjugated systems might be prepared by employing this method. Next, the reactivities of various stannanes 2 were investigated. Except in a few cases, such as very bulky substrates (3hb), the reactions proceeded smoothly to afford biaryl products with broad functional group tolerance (3hc-ii). Heterocyclic substrates reacted without difficulty, and the desired products were obtained in high yields (3hj-hm).

Several additional reactions are noteworthy, and illustrate further synthetic applications of this method for selective preparations of functional molecules (Fig. 2). First, compound 3he synthesized via the present coupling reaction could be easily transformed into the ammonium salt (1o), which underwent further coupling with a second stannane 2a to generate the p-terphenyl derivative (3oa) (Fig. 2a). Second, we focused on the fact that NR2 is often employed as a directing group in various aromatic reactions, such as Friedel–Crafts reactions and aromatic C–H functionalizations. For example, Ingleson 40 recently reported direct arene borylation (directed p-borylation) via electrophilic substitution of borenium. By combining this reaction with the current coupling reaction, p-terphenyl derivative (3ma) can also be synthesized from N,N-dimethylaniline via sequential reactions (Fig. 2b). These results clearly open up a new avenue for highly regio-controlled synthesis of multi-substituted arenes by utilizing amino groups on aromatic rings. Third, we have demonstrated that selective phenylation of an amino group can be achieved by using the ammonium salt of Padimate A, an ingredient in some sunscreens (Fig. 2c). In this reaction, the ester moiety was untouched, indicating the potential applicability of this method for late-stage derivatization of various functional molecules. Finally, benzyltrimethylammonium salt 4a also reacted smoothly with stannane to give the coupling product 5aj in excellent yield, suggesting broad applicability of this method to compounds containing a C(sp3)–N bond19 (Fig. 2d).

Mechanistic study

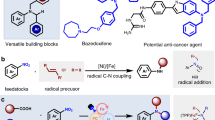

The putative mechanism of our reaction involves (A) Ni(0)-mediated C–N bond cleavage of ammonium salt Ar–NMe3+ to afford Ar1–‘Ni(II)’ species (that is, an aromatic substitution reaction of NMe3 by the electron-rich Ni0 complex), (B) transmetalation at the Ni(II) centre with Ar2SnMe3 to afford Ar1–‘Ni(II)’–Ar2 species, and finally (C) reductive elimination to give the final product with regeneration of Ni(0). While steps B and C are essentially the same as those of the conventional Stille reaction41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48, step A involving C–N bond cleavage is of particular interest. Therefore, this step was investigated in detail in the stoichiometric reaction of ammonium triflate 1m with Ni(cod)2 and ICy ligand (Table 2). At room temperature, the reaction proceeded very sluggishly in the presence of ICy·HBF4 and CsF (corresponding to the coupling conditions), and only a trace amount of the desired product was obtained. On the other hand, C–N cleavage was observed in the presence of neutral ICy ligand, with or without CsF. Higher product yields were obtained in all cases at 50 °C, and the yield was further increased at 80 °C. These results imply that CsF acts simply as a base to release free ICy ligand in this step.

After several attempts, we obtained X-ray-grade crystals from a 1,4-dioxane solution of the stoichiometric reaction mixture containing Ni(cod)2, ICy·HBF4 and CsF in a ratio of 1:2:30 (Fig. 3a,b)29. The crystal structure is that of a prototype trans-Ni(ICy)2Ar(1m)F (Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) 1438708) having a square-planar Ni(II) geometry, with two ICy ligands coordinated to the nickel atom in a trans arrangement. The compound was very stable, and even when it was treated with aqueous deuterium chloride (DCl) (0.2 mol l−1) for several hours, the C–Ni bond remained unbroken; F/Cl exchange took place instead to give trans-Ni(ICy)2Ar(1m)Cl (confirmed by X-ray diffraction analysis, CCDC 1438709; Fig. 3a,c). Furthermore, the reaction of trans-Ni(ICy)2Ar(1m)F with PhSnMe3 under the same conditions was very reluctant, indicating that this product may be a dead-end species, rather than the active intermediate of the present coupling reaction (Fig. 3a). Some important conclusions regarding the reaction mechanism of this coupling can be drawn from the data in Table 2 and Fig. 3, that is, (1) when a substantial amount of PhSnMe3 is present in the C–N bond cleavage step, the subsequent transmetalation proceeds smoothly, but (2) in the absence of PhSnMe3, the reaction affords a dead-end species, that is, trans-Ni(ICy)2ArF, which is inert to transmetalation with PhSnMe3.

The role of fluoride ion and the nature of the post C–N bond cleavage step in the present coupling reaction were investigated in model systems (Table 3). Several elegant investigations to clarify the influence of fluoride in Stille coupling reactions have already been reported41,42,43,44. In our case, when salt-free neutral ICy was used in the absence of CsF, the coupling reaction did not proceed at all. On the other hand, under the standard conditions, the reaction temperature played a crucial role in determining the coupling yield. The coupling did not occur at room temperature, but proceeded at higher temperature, and was accelerated as the temperature was increased. The yield of product 3ha reached 95% at 80 °C. These results suggest that fluoride is necessary for Ni/Sn transmetalation, which may be quite energy-demanding.

DFT calculations

Next, we employed density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the B3LYP (refs 49, 50, 51)/M06 (ref. 52) level, together with the artificial force-induced reaction method53,54, to examine in detail the mechanism of this cross-coupling reaction. The results are illustrated in Fig. 4. First, the Ni(0)−π complex CP0 is formed with −3.0 kcal mol−1 exothermicity from Ni(ICy)2 (generated from Ni[cod]2 and ICy) and [PhNMe3]+F− (generated via anion metathesis of [PhNMe3]+[OTf]− and CsF; the reaction route starting from [PhNMe3]+[OTf]− was also calculated, but there was no marked difference in geometric structure or energy profile, compared with the results shown in Fig. 4). From CP0, Ni(0) can migrate on the phenyl ring to the proximal position of the C–N bond via TS0 with an energy loss of only 10.2 kcal mol−1 to form the more stable CP1. Cleavage of the C–N bond then takes place very smoothly as a SNAr process (TS1, −2.0 kcal mol−1), with release of NMe3, affording intermediate CP2-1 with large exothermicity (−45.5 kcal mol−1). The two ICys in CP2-1 arrange in the cis-position, in which the horizontal Ni–C(ICy) bond (d2=2.01 Å) is rather longer than the vertical one (d2=1.92 Å). PhSnMe3 then approaches the Ni(II) centre in CP2-1 after the loss of one ICy ligand and rotation of the Ni–F bond from the vertical to the horizontal position (Supplementary Fig. 1) to generate CP2-2 with an overall energy loss of 18.4 kcal mol−1. To reach the TS of transmetalation, TS2, the orientation of the phenyl group of PhSnMe3 changes so that the sp2-orbital bound to the Sn metal can interact with the Ni(II) centre, and the C–Sn bond is cleaved with a small activation energy (4.1 kcal mol−1) to give CP3-1 (−27.2 kcal mol−1). CP3-1 then ejects FSnMe3 to afford the precursor for the reductive elimination, CP3-2 (−19.0 kcal mol−1). Finally, C–C bond formation proceeds smoothly through TS3 with an energy loss of only 2.3 kcal mol−1 to produce the final product, Ph–Ph, and the Ni(ICy)2 catalyst is regenerated with a large energy gain. We also carried out the experimental and theoretical studies of the possible alternative Ni(I)/Ni(III) pathway (Supplementary Figs 2–4; Supplementary Discussion). Although we cannot completely rule out the involvement of the Ni(I)/Ni(III) mechanism, and other scenarios could be contemplated, the computational and experimental results are all consistent with the view that the Ni(0)/Ni(II) route is more favourable and would be at least the predominant reaction pathway.

The computed resting-state RS (trans-isomer of CP2-1) is essentially identical with the structure obtained by X-ray diffraction analysis (Fig. 3b). RS is thermodynamically more favourable than CP2-1 by 10.4 kcal mol−1, and thus the total energy loss for the transmetalation (TS2) from RS (32.9 kcal mol−1) is much higher than that from CP2-1 (22.5 kcal mol−1), suggesting low reactivity (Fig. 4), which is in good agreement with the experimental facts.

We next examined the role of fluoride ion in the transmetalation step (Fig. 5)41,42,43,44. In the presence of fluoride ligand on the Ni(II) metal, this step is facilitated by a push-pull interaction, where F anion plays the role of a Lewis basic activator coordinating to the Sn metal to enhance the transfer ability of the Ph group of PhSnMe3, and the Ni(II) centre is activated by the F···SnMe3 interaction, allowing the Ph group to undergo smooth bond switching from Sn to Ni(II), affording the biarylated Ni(II) intermediate CP3-1 with an activation energy of only 4.1 kcal mol−1. On the other hand, CP2-2OTf with triflate anion on the Ni(II) undergoes transmetalation via a six-membered TS TS2OTf in essentially the same manner. However, transmetalation of CP2-2OTf requires much higher activation energy (19.5 kcal mol−1) than that of CP2-2. In addition, the resultant intermediate CP3-1OTf is geometrically and electronically unstable, and is thermodynamically disfavoured by 15.0 kcal mol−1 compared with CP2-2OTf. Thus, transmetalation without the assistance of fluoride anion should encounter both kinetic and thermodynamic difficulties, in accordance with the experimental facts.

DFT calculation for the transmetalation step in the presence and absence of fluoride. See Fig. 4 for details.

Discussion

Almost 40 years after the discovery of Stille coupling chemistry, we have developed the first Stille reaction of quaternary ammonium salts via C–N bond cleavage catalysed by a commercially available Ni-catalyst/ligand. Few Ni-catalysed Stille coupling reactions have been reported so far. This novel C–N type Stille reaction is expected to be a powerful tool for the straightforward transformation of various aromatic amines/quaternary ammonium salts into multi-aromatic compounds and oligo(arylene)s, which have many potential applications in pharmaceutical, agrochemical and materials sciences. We also provide the first comprehensive reaction profile of cross-coupling via C–N bond cleavage, uncovered by employing a combination of experimental and computational methods. Work to extend the scope of this reaction and to apply it for synthesis of a range of functional molecules, including extended π-conjugation systems and bioactive compounds, is in progress.

Methods

General methods

All reactions were carried out under a slightly positive pressure of dry argon by using standard Schlenk line techniques or in a glovebox (Braun, Labmaster SP). The oxygen and moisture concentrations in the glovebox atmosphere were monitored with an O2/H2O analyser to ensure both were always <0.1 p.p.m. Unless otherwise noted, all starting materials including dehydrated solvents were purchased from WAKO, KANTO, TCI or ALDRICH. Ammonium salts were prepared via reported protocols (Supplementary Methods). ArSnMe3 were prepared through the reaction of (1) Me3SnCl with corresponding aryl lithium or (2) Me3SnLi with corresponding aryl bromides/iodides. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were obtained on JEOL AL-300, AL-400 NMR and/or BRUKER AVANCE III HD spectrometers. Column chromatography was performed with silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh) from Merck and thin-layer chromatography was carried out on 0.25 mm Merck silica gel plates (60F-254).

Typical procedure for cross-coupling between 1 and 2

A Schlenk tube was charged with an aryltrimethylammonium triflate 1 (0.5 mmol), Ni(cod)2 (13.8 mg, 0.05 mmol), ICy·HBF4 (32.0 mg, 0.1 mmol), CsF (227.9 mg, 1.5 mmol), ArSnMe3 2 (0.55 mmol) and dioxane (5 ml) under an argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C overnight and then cooled to room temperature. Water (10 ml) was added and the resulting mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 ml). The combined organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel to afford product 3. Representative example: 3aa, colourless oil, isolated yield 60%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.72–7.67 (m, 2H), 7.63–7.58 (m, 2H), 7.56–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.48–7.34 (m, 3H), 2.50 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 141.25, 138.45, 137.11, 129.55, 128.82, 128.78, 127.32, 127.24, 127.07, 127.04 and 21.00. For full experimental details, see Supplementary Figs 5–68 and Supplementary Methods. For details on synthesis, characterization and deuteration of trans-Ni(ICy)2Ar(1m)X (X=F and Cl), see Supplementary Figs 69–74 and Supplementary Methods.

X-ray crystallographic analysis

Data collections were performed at 100 K on a Bruker D8 VENTURE diffractometer (PHOTON-100 CMOS detector, IμS-microsource, focusing mirrors, CuKα λ=1.54178 Å) and processed using Bruker APEX-II software. The structure was solved by SHELXT55 and refined by full-matrix least squares on F2 for all data using SHELXL56 and ShelXle57 software. All non-disordered non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically, and hydrogen atoms except those of water molecules were placed in the calculated positions. In the refinement of trans-Ni(ICy)2Ar(1m)Cl, the disordered cyclohexane rings were refined with equivalent anisotropic displacement parameters (EADP). DELU restraints were applied to solvent n-pentane, which rides on a symmetrically special position. The hydrogen atoms of solvent water were located on the difference Fourier maps and refined isotropically. DFIX and DANG restraints were applied to most of these hydrogen atoms (Supplementary Fig. 75; Supplementary Tables 4 and 5).

Computation methods

All DFT calculations were performed with the Gaussian 09 program (Revision D.01)58 and the GRRM 11 (Version 11.03 (ref. 59) based on Gaussian 09) program. Structure optimizations were carried out at the B3LYP level in the gas phase, using the LANL2DZ basis set60,61,62 for Ni and Sn, and the 6-31G* basis set63,64 for H, C, N and F (keyword five dimensional was used in the calculations). The vibrational frequencies were computed at the same level to check whether each optimized structure is an energy minimum (no imaginary frequency) or a transition state (one imaginary frequency), and to evaluate its zero-point vibrational energy and thermal corrections at 298 K. Intrinsic reaction coordinates were calculated to confirm the connection between the transition states and the reactants/products. The single-point energy considering the solvent effect of 1,4-dioxane was obtained via calculation of the B3LYP geometries with M06 functional theory, using the Stuttgart-Dresden ECP (effective core potentials) and D-basis set (SDD) basis set65,66 for Ni and Sn, and the 6-311++G basis set67,68 for other atoms. Solvation was evaluated by the self-consistent reaction field method using the polarizable continuum model69. The Gibbs free energy used for the discussion in this study was calculated by adding the gas-phase Gibbs free energy correction and the solution-phase single-point energy. Geometry of ICy was taken from the crystal structures. Original energy profiles and cartesian coordinates for DFT calculation be found in the Supplementary Data 1.

Data availability

Detailed experimental procedures and characterization of compounds can be found in the Supplementary Figs 5–75; Supplementary Methods. Original energy profiles and cartesian coordinates for DFT calculation be found in the Supplementary Data 1. Crystallographic data have been deposited with the CCDC, with deposition number CCDC-1438708 (trans-Ni(ICy)2Ar(1m)Cl) and 1438709 (trans-Ni(ICy)2Ar(1m)Cl). These data can be obtained free of charge from the CCDC via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. All other data are available from the authors on reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Wang, D.-Y. et al. Stille coupling via C–N bond cleavage. Nat. Commun. 7, 12937 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12937 (2016).

References

Azarian, D., Dua, S. S., Eaborn, C. & Walton, D. R. M. Reactions of organic halides with R3MMR3 compounds (M=Si, Ge, Sn) in the presence of tetrakis(triarylphosphine)palladium. J. Organometal. Chem. 117, C55–C57 (1976).

Kosugi, M., Shimizu, Y. & Migita, T. Alkylation, arylation, and vinylation of acyl chlorides by means of organotin compounds in the presence of catalytic amounts of tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(0). J. Organometal. Chem. 6, 1423–1424 (1977).

Milstein, D. & Stille, J. K. A general, selective, and facile method for ketone synthesis from acid chlorides and organotin compounds catalyzed by palladium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 100, 3636–3638 (1978).

Johansson Seechurn, C. C. C., Kitching, M. O., Colacot, T. J. & Snieckus, V. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling: a historical contextual perspective to the 2010 Nobel Prize. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 5062–5085 (2012).

Cordovilla, C., Bartolomé, C., Martínez-Ilarduya, J. M. & Espinet, P. The Stille reaction, 38 years Later. ACS Catal. 5, 3040–3053 (2015).

Littke, A. F., Schwarz, L. & Fu, G. C. Pd/P(t-Bu)3: a mild and general catalyst for Stille reactions of aryl chlorides and aryl bromides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 6343–6348 (2002).

Su, W., Urgaonkar, S., McLaughlin, P. A. & Verkade, J. G. Highly active palladium catalysts supported by bulky proazaphosphatrane ligands for Stille cross-coupling: coupling of aryl and vinyl chlorides, room temperature coupling of aryl bromides, coupling of aryl triflates, and synthesis of sterically hindered biaryls. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 16433–16439 (2004).

Mee, S. P. H., Lee, V. & Baldwin, J. E. Significant enhancement of the Stille reaction with a new combination of reagents—copper(I) iodide with cesium fluoride. Chem. Eur. J. 11, 3294–3308 (2005).

Dowlut, M., Mallik, D. & Organ, M. G. An efficient low-temperature Stille-Migita cross-coupling reaction for heteroaromatic compounds by Pd-PEPPSI-IPent. Chem. Eur. J. 16, 4279–4283 (2010).

Li, L., Wang, C.-Y., Huang, R. & Biscoe, M. R. Stereoretentive Pd-catalysed Stille cross-coupling reactions of secondary alkyl azastannatranes and aryl halides. Nat. Chem. 5, 607–612 (2013).

Cornella, J., Zarate, C. & Martin, R. Metal-catalyzed activation of ethers via C–O bond cleavage: a new strategy for molecular diversity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 8081–8097 (2014).

Tasker, S. Z., Standley, E. A. & Jamison, T. F. Recent advances in homogeneous nickel catalysis. Nature 509, 299–309 (2014).

Tobisu, M. & Chatani, N. Cross-couplings using aryl ethers via C–O bond activation enabled by nickel catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 1717–1726 (2015).

Su, B., Cao, Z.-C. & Shi, Z.-J. Exploration of earth-abundant transition metals (Fe, Co, and Ni) as catalysts in unreactive chemical bond activations. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 886–896 (2015).

Ouyang, K., Hao, W., Zhang, W.-X. & Xi, Z. Transition-metal-catalyzed cleavage of C–N single bonds. Chem. Rev. 115, 12045–12090 (2015).

Liu, J. & Robins, M. J. Azoles as Suzuki cross-coupling leaving groups: syntheses of 6-arylpurine 2′-deoxynucleosides and nucleosides from 6-(imidazol-1-yl)- and 6-(1,2,4-triazol-4-yl)purine derivatives. Org. Lett. 6, 3421–3423 (2004).

Ueno, S., Chatani, N. & Kakiuchi, F. Ruthenium-catalyzed carbon−carbon bond formation via the cleavage of an unreactive aryl carbon−nitrogen bond in aniline derivatives with organoboronates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 6098–6099 (2007).

Zhu, M.-K., Zhao, J.-F. & Loh, T.-P. Palladium-catalyzed C–C bond formation of arylhydrazines with olefins via carbon–nitrogen bond cleavage. Org. Lett. 13, 6308–6311 (2011).

Huang, C.-Y. D. & Doyle, A. G. Nickel-catalyzed Negishi alkylations of styrenyl aziridines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 9541–9544 (2012).

Tobisu, M., Nakamura, K. & Chatani, N. Nickel-catalyzed reductive and borylative cleavage of aromatic carbon–nitrogen bonds in n-aryl amides and carbamates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 5587–5590 (2014).

Huang, Y. & Hayashi, T. Asymmetric synthesis of triarylmethanes by rhodium-catalyzed enantioselective arylation of diarylmethylamines with arylboroxines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 7556–7559 (2015).

Weires, N. A., Baker, E. L. & Garg, N. K. Nickel-catalysed Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of amides. Nat. Chem. 8, 75–79 (2016).

Percec, V., Bae, J.-Y. & Hill, D. H. Aryl mesylates in metal catalyzed homo- and cross-coupling reactions. 4. Scope and limitations of aryl mesylates in nickel catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. J. Org. Chem. 60, 6895–6903 (1995).

Naber, J. R., Fors, B. P., Wu, X., Gunn, J. T. & Buchwald, S. L. Stille cross-coupling reactions of aryl mesylates and tosylates using a biarylphosphine based catalyst system. Heterocycles 80, 1215–1226 (2010).

Roglans, A., Pla-Quintana, A. & Moreno-Mañas, M. Diazonium salts as substrates in palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Rev. 106, 4622–4643 (2006).

Wenkert, E., Han, A.-L. & Jenny, C.-J. Nickel-induced conversion of carbon–nitrogen into carbon–carbon bonds. One-step transformations of aryl, quaternary ammonium salts into alkylarenes and biaryls. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 975–976 (1988).

Blakey, S. B. & MacMillan, D. W. C. The first Suzuki cross-couplings of aryltrimethylammonium salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 6046–6047 (2003).

Xie, L.-G. & Wang, Z.-X. Nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of aryltrimethylammonium iodides with organozinc reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 4901–4904 (2011).

Maity, P., Shacklady-McAtee, D. M., Yap, G. P. A., Sirianni, E. R. & Watson, M. P. Nickel-catalyzed cross couplings of benzylic ammonium salts and boronic acids: stereospecific formation of diarylethanes via C–N bond activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 280–285 (2013).

Buszek, K. R. & Brown, N. N-Vinylpyridinium and -ammonium tetrafluoroborate salts: new electrophilic coupling partners for Pd(0)-catalyzed Suzuki cross-coupling reactions. Org. Lett. 9, 707–710 (2007).

Reeves, J. T. et al. Room temperature palladium-catalyzed cross coupling of aryltrimethylammonium triflates with aryl Grignard reagents. Org. Lett. 12, 4388–4391 (2010).

Guo, W.-J. & Wang, Z.-X. Iron-catalyzed cross-coupling of aryltrimethylammonium triflates and alkyl Grignard reagents. Tetrahedron 69, 9580–9585 (2013).

Zhang, H., Hagihara, S. & Itami, K. Making dimethylamino a transformable directing group by nickel-catalyzed C–N borylation. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 16796–16800 (2015).

Zhu, F., Tao, J.-L. & Wang, Z.-X. Palladium-catalyzed C–H arylation of (benzo)oxazoles or (benzo)thiazoles with aryltrimethylammonium triflates. Org. Lett. 17, 4926–4929 (2015).

Moragas, T., Gaydou, M. & Martin, R. Nickel-catalyzed carboxylation of benzylic C−N Bonds with CO2 . Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 5053–5057 (2016).

Uemura, T., Yamaguchi, M. & Chatani, N. Phenyltrimethylammonium salts as methylation reagents in the nickel-catalyzed methylation of C−H bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 3162–3165 (2016).

Hu, J. et al. Nickel-catalyzed borylation of aryl- and benzyltrimethylammonium salts via C–N bond cleavage. J. Org. Chem. 81, 14–24 (2016).

Wang, D.-Y., Wang, C. & Uchiyama, M. Stannyl-lithium: a facile and efficient synthesis facilitating further applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 10488–10491 (2015).

Knochel, P. et al. Highly functionalized organomagnesium reagents prepared through halogen-metal exchange. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 4302–4320 (2003).

Del Grosso, A., Singleton, P. J., Muryn, C. A. & Ingleson, M. J. Pinacol boronates by direct arene borylation with borenium cations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 2102–2106 (2011).

Espinet, P. & Echavarren, A. M. The mechanisms of the Stille reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 4704–4734 (2004).

Hervé, M., Lefèvre, G., Mitchell, E. A., Maes, B. U. W. & Jutand, A. On the triple role of fluoride ions in palladium-catalyzed Stille reactions. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 18401–18406 (2015).

Verbeeck, S., Meyers, C., Franck, P., Jutand, A. & Maes, B. U. W. Dual effect of halides in the Stille reaction: in situ halide metathesis and catalyst stabilization. Chem. Eur. J. 16, 12831–12837 (2010).

Ariafard, A. & Yates, B. F. Subtle balance of ligand steric effects in Stille transmetalation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 13981–13991 (2009).

Pérez-Temprano, M. H., Nova, A., Casares, J. A. & Espinet, P. Observation of a hidden intermediate in the Stille reaction. Study of the reversal of the transmetalation step. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 10518–10520 (2008).

Álvarez, R., Pérez, M. & Faza, O. N. & de Lera, A. R. Associative transmetalation in the Stille cross-coupling reaction to form dienes: theoretical insights into the open pathway. Organometallics 27, 3378–3389 (2008).

Nova, A., Ujaque, G., Maseras, F., Lledós, A. & Espinet, P. A critical analysis of the cyclic and open alternatives of the transmetalation step in the Stille cross-coupling reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 14571–14578 (2006).

Ariafard, A., Lin, Z. & Fairlamb, I. J. S. Effect of the leaving ligand X on transmetalation of organostannanes (vinylSnR3) with LnPd(Ar)(X) in Stille cross-coupling reactions. A density functional theory study. Organometallics 25, 5788–5794 (2006).

Becke, A. D. A new mixing of Hartree–Fock and local density-functional theories. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 1372–1377 (1993).

Kohn, W., Becke, A. & Parr, R. G. Density functional theory of electronic structure. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 12974–12980 (1996).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789 (1988).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Account. 120, 215–241 (2008).

Maeda, S., Ohno, K. & Morokuma, K. Systematic exploration of the mechanism of chemical reactions: the global reaction route mapping (GRRM) strategy using the ADDF and AFIR methods. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 3683–3701 (2013).

Maeda, S., Taketsugu, T. & Morokuma, K. Exploring transition state structures for intramolecular pathways by the artificial force induced reaction method. J. Comput. Chem. 35, 166–173 (2014).

Sheldrick, G. M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Cryst. A71, 3–8 (2015).

Sheldrick, G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Cryst. C71, 3–8 (2015).

Hübschle, C. B., Sheldrick, G. M. & Dittrich, B. J. Appl. Cryst. 44, 1281–1284 (2011).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01 Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT (2013).

Maeda, S., Osada, Y., Morokuma, K. & Ohno, K. GRRM 11, Version 11.03 Institute of Quantum Chemical Exploration, Tokyo, (2012).

Hay, P. J. & Wadt, W. R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for the transition metal atoms Sc to Hg. J. Chem. Phys. 82, 270–283 (1985).

Wadt, W. R. & Hay, R. J. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for main group elements Na to Bi. J. Chem. Phys. 82, 284–298 (1985).

Hay, P. J. & Wadt, W. R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for K to Au including the outermost core orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 82, 299–310 (1985).

Hehre, W. J., Ditchfield, R. & Pople, J. A. Self–consistent molecular orbital methods. XII. Further extensions of Gaussian–type basis sets for use in molecular orbital studies of organic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 56, 2257–2261 (1972).

Francl, M. M. et al. Self–consistent molecular orbital methods. XXIII. A polarization–type basis set for second–row elements. J. Chem. Phys. 77, 3654–3665 (1982).

Fuentealba, P., Preuss, H., Stoll, H. & Szentpaly, L. V. A proper account of core-polarization with pseudopotentials: single valence-electron alkali compounds. Chem. Phys. Lett. 89, 418–422 (1982).

Szentpaly, L. V., Fuentealba, P., Preuss, H. & Stoll, H. Pseudopotential calculations on Rb+2, Cs+2, RbH+, CsH+ and the mixed alkali dimer ions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 93, 555–559 (1982).

Krishnan, R., Binkley, J. S., Seeger, R. & Pople, J. A. Self–consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 72, 650–654 (1980).

McLean, A. D. & Chandler, G. S. Contracted Gaussian basis sets for molecular calculations. I. Second row atoms, Z=11−18. J. Chem. Phys. 72, 5639–5648 (1980).

Tomasi, J., Mennucci, B. & Cammi, R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 105, 2999–3094 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (S) (no. 24229011; to M.U.), JSPS Grant WAKATE-B (no. 24790035; to C.W.), and JSPS TEI-SOKU Program (PU14008; to C.W.). This research was also partly supported by grants (to M.U.) from Takeda Science Foundation, Asahi Glass Foundation, Daiichi-Sankyo Foundation of Life Sciences, Mochida Memorial Foundation, Tokyo Biochemical Research Foundation, Nagase Science Technology Development Foundation, Yamada Science Foundation and Sumitomo Foundation. D.Y.W. is grateful for a scholarship provided by the Uehara Memorial Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Y.W. planned, conducted, analysed and summarized the experiments. M.K., S.K. and K.Y. performed X-ray diffraction analysis. C.W. conceived the project and performed DFT calculation. Z.K.Y. and K.M. participate in the experiments or discussions. D.Y.W., C.W. and M.U. wrote the manuscript with feedback from all authors. C.W. and M.U. supervised the research.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-75, Supplementary Tables 1-5, Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References. (PDF 1639 kb)

Supplementary Data 1

Energy Profiles for DFT Calculations and Cartesian Coordinates (DOCX 248 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, DY., Kawahata, M., Yang, ZK. et al. Stille coupling via C–N bond cleavage. Nat Commun 7, 12937 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12937

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12937

This article is cited by

-

Stereoselective C–O silylation and stannylation of alkenyl acetates

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Design of a Nanoscale Ni Catalyst for Debenzylation Reactions via Hydrogenative C–N Bond Cleavage

Catalysis Letters (2023)

-

Cross-coupling polycondensation via C–O or C–N bond cleavage

Nature Communications (2018)

-

Biomimetic Cleavage of Aryl–Nitrogen Bonds in N-Arylazoles Catalyzed by Metalloporphyrins

Catalysis Letters (2018)

-

Tin can

Nature Chemistry (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.