Abstract

Hamartomas are composed of cells native to an organ but abnormal in number, arrangement or maturity. In the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), hamartomas develop in multiple organs because of mutations in TSC1 or TSC2. Here we show that TSC2-null fibroblast-like cells grown from human TSC skin hamartomas induced normal human keratinocytes to form hair follicles and stimulated hamartomatous changes. Follicles were complete with sebaceous glands, hair shafts and inner and outer root sheaths. TSC2-null cells surrounding the hair bulb expressed markers of the dermal sheath and dermal papilla. Tumour xenografts recapitulated characteristics of TSC skin hamartomas with increased mammalian target of the rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) activity, angiogenesis, mononuclear phagocytes and epidermal proliferation. Treatment with an mTORC1 inhibitor normalized these parameters and reduced the number of tumour cells. These studies indicate that TSC2-null cells are the inciting cells for TSC skin hamartomas, and suggest that studies on hamartomas will provide insights into tissue morphogenesis and regeneration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hamartomas are benign tumours that contain components normally found in an organ, but in faulty mixture, organization or maturity1. Attempts to determine the basis for this disordered architecture have been hampered by a difficulty in identifying and propagating the inciting cell type(s). Insights into the molecular defects contributing to the formation of some hamartomas have been realized by studying hamartoma syndromes such as the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC)2.

Patients with TSC develop hamartomas in the brain, kidneys, heart, lungs and skin3. Skin hamartomas include facial angiofibromas, fibrous plaques (termed forehead fibrous plaques if in typical location) and periungual fibromas. These tumours contain fibroblast-like cells, fibrous tissue and vessels as observed in normal skin, but in abnormal arrangement and increased amounts4,5,6. Hair follicles in both angiofibromas and fibrous plaques appear variably enlarged, elongated or increased in number, whereas periungual fibromas have a thickened epidermis but no hair follicles4,5,6. The significance of these follicular changes has been mostly ignored for over 50 years7; the viewpoint that hair follicles are passively involved in tumour connective tissue5 has dominated over the suggestion that angiofibromas and forehead plaques represent hamartomatous abnormalities of hair follicles4,8.

Hair follicle morphogenesis involves a complicated multistep interaction between the fetal mesenchyme and epithelium9. Hair follicle formation can also be induced experimentally in postnatal mice and rats by combining epithelial cells with hair follicle dermal cells, specifically dermal papilla or dermal sheath cells10,11. Dermal cells from mice or rats are also able to induce human foreskin keratinocytes to form hair follicle-like structures12, but formation of human hair follicles by combining cultured postnatal human dermal and epidermal cells has not been achieved13.

TSC is caused by mutations of a tumour suppressor gene, either TSC1 or TSC2. The proteins encoded by these genes, TSC1 (hamartin) and TSC2 (tuberin), function as a complex to regulate the mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) signalling pathway14. Tumour cells typically sustain a 'second-hit' mutation that inactivates the corresponding wild-type allele, and loss of function of the TSC1–TSC2 complex activates signalling through mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1)15,16,17. These observations prompted clinical studies using mTOR inhibitors, such as rapamycin (sirolimus), to treat TSC tumours. A decrease in size of renal angiomyolipomas, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas, lymphangioleiomyomatosis and skin tumours18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 has been demonstrated. Rapamycin is likely to arrest cell growth and decrease cell size in vivo. It may also eliminate tumour cells and inhibit angiogenesis or function by some other mechanism, and this information is needed to develop new treatment strategies to completely eradicate tumours.

To elucidate mechanisms of hamartoma formation and study drug action in vivo, there was a need for a xenograft model of TSC skin tumours. The groundwork for this model was our earlier observation that fibroblast-like cells grown from most TSC skin hamartomas showed allelic deletion of TSC2, but no evidence of such two-hit cells was detected in tumour epidermis26. In the current study, TSC2-null fibroblast-like cells were incorporated into collagen and overlaid with normal neonatal foreskin keratinocytes, and these composites were grafted onto immunodeficient mice treated with or without rapamycin. This novel xenograft model replicated hamartomatous features of TSC skin tumours. Rapamycin decreased the numbers of TSC2-null cells and markedly inhibited angiogenesis. Remarkably, TSC2-null cells from some TSC skin tumours also induced hair follicle neogenesis. These studies indicate that TSC2-null cells induce the morphological changes of TSC skin hamartomas.

Results

TSC skin tumours contain TSC2-null cells

Fibroblast-like cells, fibrous tissue and vessels were more abundant in TSC skin tumours than in normal skin (Fig. 1a). Fibroblast-like cells grown from tissue explants were screened for the loss of TSC2 expression using western blotting to obtain samples that were pure or highly enriched for TSC2-null cells. Samples used in our xenografts were those in which TSC2 expression was undetectable or barely detectable, and mTORC1 was constitutively active, as indicated by hyperphosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 under conditions of serum starvation (Fig. 1b).

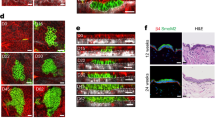

(a) Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections of a TSC patient's normal-appearing skin (NL), fibrous forehead plaque (FP), angiofibroma (AF) and periungual fibroma (PF). Scale bar: 320 μm. (b) Levels of TSC2, phosphorylated ribosomal protein S6 (pS6), S6 and β-actin as assessed by western blotting in serum-starved fibroblast-like cells isolated from NL, AF, FP and PF from different patients (P1–4). (c) Absence of hair follicles in dermal–epidermal composites grafted onto mice when made with TSC normal fibroblasts and human neonatal keratinocytes. Scale bar: 320 μm. (d) Formation of hair follicles in dermal–epidermal composites grafted onto mice when composed of TSC2-null cells from a TSC fibrous forehead plaque and human neonatal keratinocytes. Scale bar: 320 μm.

TSC2-null cells induce hair follicles

To test the hypothesis that TSC2-null cells are sufficient to induce morphological abnormalities of TSC skin hamartomas, we grafted TSC skin tumour cells orthotopically onto immunodeficient mice (Supplementary Fig. S1). For grafting, we adapted an extensively used system of in vitro-constructed dermal–epidermal composites, which form stratified epithelia but not hair follicles27. Our model used normal human neonatal foreskin keratinocytes with accompanying melanocytes, growing on a collagen matrix embedded with TSC2-null fibroblast-like cells or with fibroblasts from normal-appearing skin of the same patient (hereafter called TSC normal fibroblasts). In mice, killed 17 weeks after grafting, grafts containing TSC normal fibroblasts formed skin without hair follicles (Fig. 1c). In contrast, grafts containing TSC2-null cells from some TSC skin tumours formed hair follicles (Fig. 1d). Hair follicles were observed using TSC2-null cells from three out of five patients, with follicles forming in 9 out of 18 grafts from these samples (Table 1). These results suggested that TSC skin tumour cells induced follicular neogenesis in foreskin keratinocytes.

Hair follicles in the grafts were appropriately spaced and anatomically complete. A hair shaft, sebaceous glands, concentric layers of inner and outer root sheaths surrounded by a dermal sheath and hair bulb with dermal papilla, hair matrix and cortex were all present (Fig. 2a–d). Hair follicles in all phases of the hair cycle were observed. As in facial skin, more follicles were in catagen (regressing) and telogen (resting) than in anagen (growing; Fig. 1d). Hair shafts emerged from the skin surface but were not visible grossly, perhaps reflecting the origin of TSC2-null cells from regions of the face where hair is not visible.

Representative stained sections of grafts obtained 17 weeks after grafting dermal–epidermal composites. (a) Hair follicles with sebaceous gland. (b) Longitudinal section of hair follicle with hair shaft. (c) Oblique section of hair follicle sebaceous glands and outer root sheath, inner root sheath and hair shaft. (d) Hair bulb with dermal papilla, lower dermal sheath, matrix and inner and outer root sheaths. (e) Epithelial cells and scattered dermal cells reactive with human-specific COX-IV antibody. (f) Hair follicle and dermal sheath cells reactive to COX-IV antibody. (g) Signals for a human Y-chromosome probe (red) mark foreskin-derived keratinocytes observed in the epidermis and hair follicles but not in dermal cells; DAPI (blue) nuclear stain. (h) Signals for Y-chromosome probe in follicular epithelium but not in the surrounding dermal sheath. (i) Human-specific nestin antibody reactive with cells in the dermal papilla and lower dermal sheath region. (j) Nestin antibody reactive with cells in the dermal papilla and hair bulb dermal sheath. (k) Human-specific versican antibodies reactive with mesenchymal cells of the dermal papilla and lower dermal sheath region of hair follicles. (l) Alkaline phosphatase activity localized in dermal papilla and lower sheath region of hair follicles. (m) Reactivity with antibodies against Ki-67, scattered in the basal layer of the epidermis and dense in the hair follicle matrix. (n) Keratin 15 immunoreactivity below follicular infundibulum. (o) Keratin 15 immunoreactivity in the basal layer of the outer root sheath. (p) Keratin 75 immunoreactivity in the hair follicle companion layer. Results shown are from patient 4; similar patterns of staining were observed in at least four tumour xenografts from patient 4 and in two tumour xenografts from patient 5. Scale bars in a, b, e, g are 130 μm; for i, k, l, m, n, o, p are 65 μm; for c, d, f, j are 35 μm; and for h is 20μm.

Xenograft hair follicles are human and fully developed

The hair shafts lacked the regularly spaced air pockets of murine hair, consistent with human origin. To establish the species of origin of the follicles, we performed immunohistochemistry with antibody reactive with human but not mouse COX-IV28. Immunoreactivity was observed in the follicles, epithelium and dermis of xenografts (Fig. 2e,f). Similar results were obtained using a pan-human HLA class I monoclonal antibody (Supplementary Fig. S2a), with interfollicular epidermis staining more intensely than follicular epithelium, as expected in normal human skin29. To distinguish between human foreskin keratinocytes and TSC2-null cells from female patients, we performed fluorescence in situ hybridization using a probe for the human Y-chromosome. The probe hybridized to nuclei in the epidermis and the follicular epithelium but not to the nuclei of dermal cells (Fig. 2g,h; Supplementary Fig. S2b). These results show that foreskin keratinocytes were induced to differentiate into several cellular components that compose normal hair follicles, confirming de novo hair follicle induction.

To confirm further the normality of induced hair follicles, we used immunohistochemistry to identify markers of specific compartments of fully developed human hair follicles. Cells in the region of the dermal papilla and lower dermal sheath showed normal reactivity30,31 with specific antibodies to human nestin (Fig. 2i,j) and human versican (Fig. 2k), and displayed alkaline phosphatase activity (Fig. 2l). Immunoreactivity for Ki-67 was concentrated in the region of the hair matrix (Fig. 2m), typical of active anagen phase proliferation with robust hair shaft formation. Keratin 15, a marker of hair follicle stem cells located in the bulge region32, was localized in the basal layer of the outer root sheath (Fig. 2n,o), as observed in human angiofibromas8. Immunoreactivity for keratin 75, a marker of the companion layer, was present in a single layer of cells between the inner and outer root sheaths (Fig. 2p), as observed in normal human hair33. Thus, by both morphological and immunohistochemical criteria34, fully developed human hair was present in xenografted skin.

Mutations in TSC2 identify tumour cells in xenografts

To demonstrate the presence of TSC2-null cells in the dermal papilla/lower dermal sheath regions of induced follicles, we investigated the genetic identity of these cells. Sequencing of TSC2-null cells from a fibrous forehead plaque revealed a nonsense mutation in the TSC2 gene, 1074G>A in exon 10, which converted UGG encoding tryptophan to the stop codon UGA (Fig. 3a). These cells also showed loss of heterozygosity at three microsatellite markers flanking the TSC2 gene (Fig. 3b), rendering the cells homo- or hemi-zygous for the point mutation in exon 10. The point mutation introduced a new restriction site for BsmA1 cleavage of PCR-amplified tumour DNA. Patient normal fibroblasts did not contain the mutation, which was present in additional skin tumour cells from this patient (Fig. 3c). These results are consistent with mosaicism for the point mutation in this patient with sporadic TSC. Sections of xenografts were microdissected (Fig. 3d) for restriction enzyme analysis that revealed mutant DNA in cells from the region of the dermal papilla/lower dermal sheath, but not in follicular epithelium (Fig. 3c). The presence of TSC2-null cells in this region suggests that TSC tumour fibroblast-like cells are oligopotent progenitor cells that can exhibit features of dermal fibroblasts or dermal papilla/dermal sheath cells.

Upper panels a–d show results using samples from patient 4, and lower panels e–h show results using samples from patient 2. (a) Sequencing of DNA from TSC2-null cells from a forehead plaque revealed a single-base substitution (1074G>A) in exon 10 of the TSC2 gene. (b) Analysis of microsatellite nucleotide-repeat polymorphisms flanking TSC2 at 16p13.3. Alleles are marked with arrowheads for the patient's normal fibroblasts and TSC2-null cells. (c) Restriction enzyme analysis of a part of exon 10 of TSC2, using PCR-amplified DNA from TSC normal fibroblasts (normal), TSC2-null cells from a forehead plaque (tumour), laser microdissected follicular epithelium (FE) or dermal sheath (DS) regions of tumour xenografts, and fibroblast-like cells derived from two angiofibromas (AF1 and AF2) and one oral fibroma (OF). The mutation 1074G>A introduces a restriction site for BsmA1, so that mutant but not normal DNA is cleaved. (d) Tumour xenografts were microdissected using laser microdissection (laser track in red), including the DS and FE. (e) Sequence analysis shows a single-base substitution (4830G>A) in exon 36 of TSC2 in fibroblasts from patient's normal-appearing skin and TSC2-null cells from a periungual fibroma. (f) Restriction enzyme analysis of a part of exon 36 of TSC2, using PCR products amplified from normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHDF), TSC patient's fibroblasts (normal) and TSC2-null periungual fibroma cells (tumour). The mutation 4830G>A eliminates a restriction site for BslI, so that wild-type but not mutant DNA is cleaved. (g) Sequence analysis of the TSC2 gene in TSC2-null cells reveals a deletion of two base pairs, 1058_1059delTC, in exon 10 indicated by the arrow. (h) Restriction enzyme analysis of a part of exon 10 of TSC2, using PCR products from TSC normal fibroblasts (normal), TSC2-null cells (tumour) and laser microdissected dermis of normal and tumour xenografts. The mutation 1058_1059delTC eliminates a restriction site for SacI, so that wild-type but not mutant DNA is cleaved.

Certain grafts did not form follicles; therefore, we examined whether there was selective loss of mutant cells in these grafts. Sequencing identified two point mutations in TSC2 in periungual fibroma cells from patient 2. One mutation, 4830G>A, was present in both patient's normal fibroblasts and tumour cells and therefore represents the germline mutation (Fig. 3e,f). The second mutation, 1058_1059delTC, was identified only in the tumour and therefore represents the somatic mutation (Fig. 3g,h). Analysis of DNA extracted from laser microdissected dermis of grafts confirmed the presence of the somatic mutation in tumour but not normal grafts (Fig. 3h). These results indicate that failure to form follicles by these periungual fibroma cells is not due to absence of TSC2-null cells.

Angiofibroma cells express certain dermal papilla genes

To gain insights into the capacity of TSC2-null cells from TSC skin tumours to induce hair follicles, we compared gene expression data from GEO data set GDS3281, comprising TSC angiofibroma cells and TSC normal fibroblasts in paired samples from four patients26, with homologous genes upregulated in mouse dermal papilla cells35,36. Of the 468 mouse dermal papilla genes, levels of 115 human homologues in cultured TSC angiofibroma cells were twofold or more compared with those in TSC normal fibroblasts, including eight genes significantly increased (P<0.05; Supplementary Table S1).

Activated mTORC1 and altered composition of TSC skin tumours

To determine the extent to which our xenograft model recapitulated TSC skin hamartomas, we characterized the histological (Supplementary Fig. S3a,b) and immunohistochemical changes in fibrous plaques as a baseline for comparison. Fibroblast-like cells from TSC fibrous plaques, such as angiofibromas and ungual fibromas26,37, show greater immunoreactivity for phosphorylated ribosomal protein S6 (pS6) than do TSC normal fibroblasts (Supplementary Fig. S3c,d), consistent with elevated mTORC1 activity in TSC2-null cells. The epidermis of TSC skin tumours also exhibits greater immunoreactivity for pS6 (Supplementary Fig. S3c,d), as well as greater proliferation (Supplementary Fig. S3e,f), than does normal skin. This may be caused by paracrine factors released by the TSC2-null cells26. These changes in hamartoma fibroblast-like cells and epidermal cells are accompanied by marked increases in two additional cellular constituents, CD68-positive mononuclear phagocytes and CD31-positive blood vessels (Supplementary Fig. S3g,h and i,j, respectively). It is possible that TSC fibroblast-like cells induce angiogenesis directly through the release of angiogenic factors or indirectly by recruiting proangiogenic mononuclear phagocytes37.

Rapamycin reverses changes induced by TSC2-null cells

We used our xenograft model to determine whether TSC2-null cells were able to induce cytological and biochemical alterations, as well as to test the effects of rapamycin, an mTORC1 inhibitor. Our in vitro studies showed that rapamycin blocked mTORC1 activation in TSC2-null cells (Fig. 4a) and decreased in vitro viability of TSC2-null cells to a greater extent than of TSC normal fibroblasts (Fig. 4b). To study the effects of rapamycin in vivo, we administered rapamycin (2 mg kg−1), or an equal volume of vehicle, by intraperitoneal injection on alternate days for 12 weeks, beginning 5 weeks after grafting, to nude mice grafted with composites containing either TSC2-null cells from a fibrous plaque or TSC normal fibroblasts. Mice were killed 24 h after the last injection for analysis of grafts by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4c). There were no gross differences in size or appearance between tumour and normal grafts in mice with or without rapamycin treatment. Tumour grafts contained numbers of COX-IV-positive cells in the dermis similar to those in normal grafts (Fig. 4d), but greater numbers of dermal cells immunoreactive for pS6 (Fig. 4e). The epidermis of tumour grafts had greater intensity of staining for pS6 (Fig. 4f) and greater numbers of Ki-67-positive cells (Fig. 4g) than that of normal grafts. These findings strengthen our conclusion that the presence of TSC2-null cells resulted in greater proliferation and mTORC1 activation of the overlying epidermis (consistent with human tumours), as tumour grafts and normal grafts were generated using the same neonatal foreskin keratinocytes. Tumour grafts contained greater numbers of mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 4h) and higher vessel density, larger vessel size and total vessel area (Fig. 4i–k) than normal grafts. Qualitatively similar changes were observed comparing TSC2-null cells from the other patient fibrous plaques, angiofibromas and periungual fibroma with control grafts constructed from TSC normal fibroblasts. These results show that TSC2-null cells are sufficient to induce hamartomatous features of TSC skin tumours.

(a) Western blot of serum-starved cells treated with or without rapamycin (2 nM) for 24 h. Levels of phosphorylated S6K1 (pS6K1), total S6K1, pS6, total S6 and β-actin were assessed in TSC fibroblasts (normal) and in cells from a forehead plaque (tumour). Similar results were obtained using cells from a periungual fibroma. (b) Inhibition of cell viability measured using MTT assay in TSC normal fibroblasts (white bars) and TSC2-null cells from a fibrous forehead plaque (black bars) treated with or without rapamycin for 3 days. Results are mean±s.d. of values from four experiments. *P<0.01. Similar results were obtained using TSC2-null cells from a periungual fibroma. Panels c–k display the in vivo effects of rapamycin in mice with composite grafts containing TSC2-null cells or TSC normal fibroblasts from patient 4. (c) Immunohistochemistry for human COX-IV, pS6, Ki-67 (proliferation), F4/80 (phagocytes) and CD31 (vessels) in four experimental groups: NV, TSC normal fibroblasts with vehicle treatment; NR, TSC normal fibroblasts with rapamycin treatment; TV, TSC2-null cells with vehicle treatment; TR, TSC2-null cells with rapamycin treatment. Scale bar: 35 μm. Staining was quantified as shown in d–k. White and black bars indicate means±s.e. for vehicle- and rapamycin-treated animals, respectively. (d) Density of dermal cells reactive with human-specific COX-IV. (e) Density of dermal cells reactive with pS6. (f) Intensity of staining for pS6 in the epidermis. (g) Numbers of non-follicular epidermal cells reactive with Ki-67 relative to epidermal length. (h) Density of dermal cells reactive with F4/80. (i) Density of CD-31 positive vessels. (j) Average cross-sectional area of CD-31 positive vessels. (k) The ratio of vessel area to dermal area within grafts. Numbers of mice were 13 for NV, 14 for NR, 12 for TV and 15 for TR. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Rapamycin decreased human dermal cell number in tumour xenografts but had no significant effects on cell number in normal xenografts (Fig. 4c,d and Supplementary Fig. S4a,b). TSC2-null cells persisted despite in vivo penetration of rapamycin, as shown by loss of pS6 immunoreactivity in dermal and epidermal cells (Fig. 4e,f). Rapamycin treatment decreased the number of Ki-67-positive epidermal cells, mononuclear phagocytes and vessel density, size and total area in tumour grafts (Fig. 4g–k). Rapamycin did not influence the percentage of grafts with hair follicles, hair follicle density or hair follicle diameter (Table 2).

Discussion

Our results indicate that TSC2-null fibroblast-like cells are the inciting cells for TSC skin hamartomas. When these cells are grafted onto mice as composites overlaid with normal newborn keratinocytes, the grafted skin manifests features of TSC skin tumours. TSC2-null cells directly or indirectly regulate multiple cell types, stimulating angiogenesis, recruiting mononuclear phagocytes, increasing epidermal proliferation and inducing follicular neogenesis. The capacity of TSC2-null cells to induce normal keratinocytes to form follicular epithelium suggests that TSC hamartomas reflect ongoing attempts at fetal tissue morphogenesis, whereby tumour cells continue to convey inductive signals to other cells forming the tissue, as postulated by Sylvan Moolten in 1942 (ref. 38).

TSC2-null cells from certain samples appeared to have a greater capacity for inducing hair follicles than did others. Sources of variability include patient age (samples from patients under the age of 32 years induced follicles, whereas those from patients over 37 years did not) and tumour type (cells from a periungual fibroma, a tumour type that does not contain hair follicles, did not induce follicles). Cell passage number is also expected to influence results as hair follicle induction in mouse dermal cells decreased with repeated passage of dermal cells39 or keratinocytes12. We grafted early passage cells, but it is notable that tumour cells that induced follicles were combined with passage 3 keratinocytes and those that failed to induce hair follicles were combined with passage 4–5 keratinocytes. Other potentially confounding factors are differences in mutations or developmental timing of second-hit mutations. Additional studies are required to determine the relative importance of these variables on follicle-inducing capacity.

TSC2-null cells overexpress certain genes that are characteristic of dermal papilla cells; hence, follicle-inducing tumour cells may share origins with hair follicle dermal cells. Some genes characteristically expressed by follicle-inducing cells, such as nestin, versican and alkaline phosphatase, were not overexpressed by TSC2-null cells in vitro, but were clearly 'turned on' in vivo in the follicular microenvironment. Differences in gene expression patterns between TSC2-null cells and murine dermal papilla cells might reflect differences between species or alterations in gene expression related to loss of TSC2 function. Further studies are necessary to determine the relationship between loss of TSC2 function and the capacity of these cells to induce hair follicles, although studies of other cell lineages in mice suggest that loss of Tsc1/Tsc2 function alters differentiation of multipotent progenitor cells. The loss of Tsc2 in radial glia increases a progenitor pool and decreases the number of neurons40, whereas deletion of Tsc1 in hematopoietic stem cells increases granulocyte-monocyte progenitors and decreases megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors41. Loss of TSC2 function in skin tumour cells may skew the differentiation of dermal cells towards follicle-inducing cells and/or promote the preservation of follicle-inducing capability in vitro.

Rapamycin decreased numbers of TSC2-null cells and mononuclear phagocytes, as well as angiogenesis and epidermal proliferation. These results suggest that the decreased redness and size of TSC skin lesions observed in patients receiving systemic21 or topical24 rapamycin may result from both antitumour cell effects and antiangiogenic effects. The antiangiogenic effects of rapamycin may be due to direct inhibition of vascular endothelium and/or indirect effects, such as diminished release of angiogenic factors by TSC2-null cells or recruitment of proangiogenic mononuclear cells. Rapamycin did not significantly affect hair follicle number or density. The lack of effect on hair follicle parameters may indicate that induction of follicles is mTORC1 independent, or that rapamycin was ineffective after follicular neogenesis had commenced.

TSC2-null cells from angiofibromas and fibrous plaques are tools for exploring follicular morphogenesis and regeneration. The fact that TSC skin tumours usually arise postnatally suggests the possibility of creating or amplifying the numbers of follicle-inducing cells via agents or stimuli affecting the TSC1/TSC2/mTORC1 pathway and/or signalling pathways involved in the genesis of other follicular hamartomas. Just as studies of cancers have revealed mechanisms of cellular growth and proliferation, studies of hamartomas should provide insights into tissue organization and maturation.

Methods

Tumour samples and cell culture

Patients were diagnosed with TSC according to clinical criteria42 and enrolled in NHLBI Institutional Review Board–approved protocol 00-H-0051. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Skin samples from TSC patients were bisected in order to use one portion for histology and the other for cell culture. To isolate fibroblast-like cells, the skin biopsy samples from TSC patients were cut into small pieces and placed in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in culture dishes. The medium was changed twice weekly until the fibroblasts migrated out to cover the dishes. Cells were collected for serial passage and cryopreservation43. Keratinocytes were isolated from foreskins of unidentified normal neonates (provided by Dr Jonathan Vogel, NCI) and grown using standard methods44. Briefly, tissues were treated overnight with Dispase (Becton Dickinson Labware) at 4 °C. Epidermal sheets were separated from dermal sheets and digested with 0.05% Trypsin 0.53 mM EDTA (Invitrogen) at 37 °C for 20 min. Cells were collected and placed on tissue culture dishes in keratinocyte serum-free media (Invitrogen) supplemented with bovine pituitary extract and recombinant epidermal growth factor.

Cell treatment and protein measurement

Cells from TSC patients were seeded into 60-mm dishes at 5×105 cells in DMEM with 10% FBS and treated with or without 2 nM rapamycin (EMD Biosciences) in serum-free DMEM for 24 h. Cells were lysed in protein extraction buffer (20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 20 mM NaF, 2.5 mM Na2P4O7, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM benzamidine, 10 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride) for quantification of TSC2 and pS6 by western blot as described26,37. Briefly, total proteins were separated in 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels and transferred to 0.45-μm Invitrolon PVDF membranes (Invitrogen) before immunoblotting with anti-TSC2 (C-20, Santa Cruz), anti-phospho-S6 ribosomal protein (Ser-235/236), anti-S6 ribosomal protein antibodies (Cell Signaling), or β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (GE Healthcare) and a SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence detection kit (Pierce).

Cell viability assay

Cells from TSC patients were seeded in 96-well plates (2,000 cells per well) with 10% FBS/DMEM and treated with rapamycin (0, 0.2, 2, 20 nM) for 3 days. Cell viability was assessed using a MTT kit (CellTiter 96 Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega).

Creation of composites

Three-dimensional in vitro composites were prepared for grafting using established methods45, modified as described. Briefly, TSC2-null cells or TSC normal fibroblasts (passages 3–5) were mixed with 1 mg ml−1 of rat tail collagen type 1 (BD Biosciences) in 10% FBS/DMEM and added to six-well Transwell plates (Corning Incorporated) at 0.5×106 cells per well. The dermal constructs were grown in 10% FBS/DMEM for 3 days before addition of 106 foreskin keratinocytes on top. The dermal–epidermal composites were incubated for 2 days submerged in DMEM and Ham's F12 (3:1) (GIBCO/Invitrogen) containing 0.1% FBS, after which the composites were brought to the air–liquid interface and grown for another 2 days in DMEM and Ham's F12 (1:1) containing 1% FBS.

Mouse grafting

Female 6- to 8-week-old Cr:NIH(S)-nu/nu mice (FCRDC, Frederick, MD) were anaesthetized using inhalant anaesthesia with isoflurane (2–4%). The grafting area on the mouse back was washed with povidine and 70% ethanol and excised using scissors. Composites were placed on the graft bed, covered with sterile petrolatum gauze and secured with bandages. The bandages were changed at 2 weeks and removed after 4 weeks.

Animal treatment

Mice grafted with composites were treated with rapamycin (2 mg kg−1) or vehicle (0.9% NaCl, 5% polyethylene glycol and 5% Tween-80) every other day by intraperitoneal injection, as used in other mouse models46,47. Mice were treated for 12 weeks starting 5 weeks after grafting. All mouse experiments were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations following protocol approval by the USUHS Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Immunohistochemistry and quantification

Paraffin sections were deparaffinized and boiled in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 min. Frozen sections were fixed in acetone at −20 °C for 10 min. All sections were stained for cellular markers using specific antibodies and the Vectastain ABC-AP kit or the Elite ABC kit with Vector Red or DAB substrate, respectively (Vector Laboratories). Numbers of positive cells, staining intensities and areas were quantified using an Olympus BX40 microscope (Olympus) and Openlab 4.0 software (Improvision). Paraffin sections were stained for COX-IV (1:500, 3E11, Cell Signaling), Nestin (1:30,000, 10C2, Millipore), Versican (1:1,000, V0/V1 Neo, Thermo scientific), keratin 15 (1:5,000, PCK-153P, Covance), keratin 75 (1:1,000, K6hf, Progen Biotechnik GmbH), pS6 (1:200, #2211, Cell Signaling), CD68 (1:50, KP1, DakoCytomation) and mouse CD31 (1:30, ab28364, Abcam). Frozen sections were stained with HLA-ABC (1:20, W6/32, Serotec), Ki-67 (1:250, SP6, Thermo Scientific) and F4/80 (1:1,000, Cl:A3-1, Abcam).

In situ alkaline phosphatase activity assay

Frozen sections were fixed in acetone for 10 min and incubated with preequilibration buffer (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.5, 0.1% Tween-20) for 15 min at room temperature. BM Purple AP substrate (Roche) was applied for 2 h. The reaction was stopped with 20 mM EDTA in PBS.

Laser microdissection and DNA isolation

Cryosections were placed on Leica slides (Leica Microsystems) for membrane-based laser microdissection. Cells from dermal sheath/dermal papilla, follicular epithelium, dermis and interfollicular epidermis were microdissected using the LEICA AS LMD laser dissection microscope (Leica). DNA was isolated using the PicoPure DNA Isolation kit (Molecular Devices).

TSC2 sequence analysis

DNA isolated from TSC2-null fibroblast-like cells was sequenced for TSC2 mutations by Athena Diagnostics. A part of exon 10 of TSC2 was amplified using AmpliTaq gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems) and PCR primers 5′-TGGTGTCCTATGAGATCGTCC-3′ and 5′-AAGGAGCCGTTCGATGTT-3′ (for 1074G>A) or 5′-AAGCAGCTCTGACCCTGTGT-3′ and 5′-CACTGCGAATCACCAGAGAA-3′ (for 1058_1059delTC). The PCR product was purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction kit (QIAGEN) and sequenced using the 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). To confirm DNA mutations using restricted enzyme digestion, PCR products were amplified using primers of 5′-TGGTGTCCTATGAGATCGTCC-3′ and 5′-AAGGAGCCGTTCGATGATGTT-3′. The products were digested with BsmA1 or SacI for detecting 1074G>A or 1058_1059delTC, respectively, and separated by electrophoresis in 10% Novex TBE (Tris-Borate-EDTA) polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen). Part of exon 36 was amplified and sequenced using primers of 5′-CAATGAGCATGGCTCCTACA-3′ and 5′-GGCACCTCCTGATTACTCCA-3′. The mutation of 4830G>A in exon 36 was confirmed by PCR amplification using primers of 5′-TCATCGAGCTGAAGGACTGC-3′ and 5′-AGGCCGTACCTTGCATGAT-3′, followed by restricted enzyme digestion with BslI and electrophoresis in 10% TBE gels.

Loss of heterozygosity analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from TSC patient cells using DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (QIAGEN) and amplified by PCR with primers flanking microsatellite loci D16S291, D16S521 and D16S663 on chromosome 16p13 (ref. 48). One primer of each pair was fluorescently labelled with 6-FAM during synthesis (Invitrogen). PCR products were denatured in formamide containing GeneScan-500 (Rox) size standards and separated on the Genetic Analyzer 3100 (PE Biosystems) capillary electrophoresis system.

Y-chromosome fluorescence in situ hybridization

The presence of male-derived human cells in xenografts was analysed using the Vysis CEP Y (DYZ1) SpectrumOrange probe (Abbot Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 8-μm cryosections were air-dried for 20 min before incubating in 2× SSC at 37 °C for 20 min. Following sequential dehydration in ethanol, sections were treated with 10 mM HCl plus 0.006% pepsin at 37 °C for 5 min and washed twice in PBS before dehydrating and air-drying. Sections were denatured in 70% formamide, 2× SSC at 73 °C for 5 min and dehydrated before hybridizing overnight with probe mixture (7 μl of CEP hybridization buffer, 2 μl of water and 1 μl of probe) at 42 °C. The sample was washed twice at 68 °C with 2× SSC, 0.1% NP-40 and counterstained by applying 10 μl of DAPI (Vector Laboratories) on each target area.

Gene array analysis

Gene array data deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database26, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (GEO accession GSE9715 and GEO data set GDS3281), were analysed for levels of genes in TSC angiofibroma cells that were twofold or more than those in TSC normal fibroblasts. Affymetrix gene probes that were assigned an 'absent' call in all samples were excluded from the list, and significance was defined as P<0.05 using a two-tailed t-test. Genes overexpressed by TSC angiofibroma cells were intersected with the human homologues of dermal papilla genes listed in Supplementary Table S6 in Rendl et al.35 and Supplementary Table S1 in Driskell et al.36

Statistical analysis

Means and standard errors (s.e.) of data were analysed by two-way analysis of variance with interaction between two factors. One factor is the treatment group (vehicle and rapamycin) and the other is the cell source (normal and tumour). If significant, a Tukey–Kramer multiple pairwise comparison procedure was used for assessing the difference of one group from others. Significance was defined as P<0.05, and all statistical tests were two-sided. PC SAS version 9.2 software was used for statistical analysis.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Li, S. et al. Human TSC2-null fibroblast-like cells induce hair follicle neogenesis and hamartoma morphogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2:235 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1236 (2011).

References

Albrecht, E. Uber hamartome. Verh. Dtsch. Ges. Pathol. 7, 153–157 (1904).

Darling, T. N. Hitting the mark in hamartoma syndromes. Adv. Dermatol. 22, 181–200 (2006).

Curatolo, P., Bombardieri, R. & Jozwiak, S. Tuberous sclerosis. Lancet 372, 657–668 (2008).

Butterworth, T. & Wilson, M. Dermatologic aspects of tuberous sclerosis. Arch. Dermatol. Syphilol. 43, 1–41 (1941).

Nickel, W. R. & Reed, W. B. Tuberous sclerosis. Special reference to the microscopic alterations in the cutaneous hamartomas. Arch. Dermatol. 85, 209–226 (1962).

Reed, R. J. & Ackerman, A. B. Pathology of the adventitial dermis. Anatomic observations and biologic speculations. Hum. Pathol. 4, 207–217 (1973).

Ackerman, A., Reddy, V. & Soyer, H. Fibrous papule. in Neoplasms with Follicular Differentiation (eds Ackerman, A., Reddy, V. & Soyer, H.) 175–190 (Ardor Scribendi, 2001).

Misago, N., Kimura, T. & Narisawa, Y. Fibrofolliculoma/trichodiscoma and fibrous papule (perifollicular fibroma/angiofibroma): a revaluation of the histopathological and immunohistochemical features. J. Cutan. Pathol. 36, 943–951 (2009).

Millar, S. E. Molecular mechanisms regulating hair follicle development. J. Invest. Dermatol. 118, 216–225 (2002).

Weinberg, W. C. et al. Reconstitution of hair follicle development in vivo: determination of follicle formation, hair growth, and hair quality by dermal cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 100, 229–236 (1993).

Jahoda, C. A., Reynolds, A. J. & Oliver, R. F. Induction of hair growth in ear wounds by cultured dermal papilla cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 101, 584–590 (1993).

Ehama, R. et al. Hair follicle regeneration using grafted rodent and human cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 127, 2106–2115 (2007).

Yang, C. C. & Cotsarelis, G. Review of hair follicle dermal cells. J. Dermatol. Sci. 57, 2–11 (2010).

Kwiatkowski, D. J. & Manning, B. D. Tuberous sclerosis: a GAP at the crossroads of multiple signaling pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, R251–R258 (2005).

Niida, Y. et al. Survey of somatic mutations in tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) hamartomas suggests different genetic mechanisms for pathogenesis of TSC lesions. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69, 493–503 (2001).

Karbowniczek, M., Yu, J. & Henske, E. P. Renal angiomyolipomas from patients with sporadic lymphangiomyomatosis contain both neoplastic and non-neoplastic vascular structures. Am. J. Pathol. 162, 491–500 (2003).

Crino, P. B., Aronica, E., Baltuch, G. & Nathanson, K. L. Biallelic TSC gene inactivation in tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurology 74, 1716–1723 (2010).

Wienecke, R. et al. Antitumoral activity of rapamycin in renal angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 48, e27–e29 (2006).

Franz, D. N. et al. Rapamycin causes regression of astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis complex. Ann. Neurol. 59, 490–498 (2006).

Bissler, J. J. et al. Sirolimus for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 140–151 (2008).

Hofbauer, G. F. et al. The mTOR inhibitor rapamycin significantly improves facial angiofibroma lesions in a patient with tuberous sclerosis. Br. J. Dermatol. 159, 473–475 (2008).

Koenig, M. K., Butler, I. J. & Northrup, H. Regression of subependymal giant cell astrocytoma with rapamycin in tuberous sclerosis complex. J. Child Neurol. 23, 1238–1239 (2008).

Haidinger, M. et al. Sirolimus in renal transplant recipients with tuberous sclerosis complex: clinical effectiveness and implications for innate immunity. Transpl. Int. 23, 777–785 (2010).

Haemel, A. K., O'Brian, A. L. & Teng, J. M. Topical rapamycin: a novel approach to facial angiofibromas in tuberous sclerosis. Arch. Dermatol. 146, 715–718 (2010).

Krueger, D. A. et al. Everolimus for subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 1801–1811 (2010).

Li, S. et al. Mesenchymal-epithelial interactions involving epiregulin in tuberous sclerosis complex hamartomas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 3539–3544 (2008).

Metcalfe, A. D. & Ferguson, M. W. Tissue engineering of replacement skin: the crossroads of biomaterials, wound healing, embryonic development, stem cells and regeneration. J. R. Soc. Interface 4, 413–437 (2007).

Aschrafi, A. et al. MicroRNA-338 regulates local cytochrome c oxidase IV mRNA levels and oxidative phosphorylation in the axons of sympathetic neurons. J. Neurosci. 28, 12581–12590 (2008).

Meyer, K. C. et al. Evidence that the bulge region is a site of relative immune privilege in human hair follicles. Br. J. Dermatol. 159, 1077–1085 (2008).

Soma, T., Tajima, M. & Kishimoto, J. Hair cycle-specific expression of versican in human hair follicles. J. Dermatol. Sci. 39, 147–154 (2005).

Sellheyer, K. & Krahl, D. Spatiotemporal expression pattern of neuroepithelial stem cell marker nestin suggests a role in dermal homeostasis, neovasculogenesis, and tumor stroma development: a study on embryonic and adult human skin. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 63, 93–113 (2010).

Cotsarelis, G. Epithelial stem cells: a folliculocentric view. J. Invest. Dermatol. 126, 1459–1468 (2006).

Sperling, L. C., Hussey, S., Sorrells, T., Wang, J. A. & Darling, T. Cytokeratin 75 expression in central, centrifugal, cicatricial alopecia—new observations in normal and diseased hair follicles. J. Cutan. Pathol. 37, 243–248 (2010).

Chuong, C. M., Cotsarelis, G. & Stenn, K. Defining hair follicles in the age of stem cell bioengineering. J. Invest. Dermatol. 127, 2098–2100 (2007).

Rendl, M., Lewis, L. & Fuchs, E. Molecular dissection of mesenchymal-epithelial interactions in the hair follicle. PLoS Biol. 3, e331 (2005).

Driskell, R. R., Giangreco, A., Jensen, K. B., Mulder, K. W. & Watt, F. M. Sox2-positive dermal papilla cells specify hair follicle type in mammalian epidermis. Development 136, 2815–2823 (2009).

Li, S. et al. MCP-1 overexpressed in tuberous sclerosis lesions acts as a paracrine factor for tumor development. J. Exp. Med. 202, 617–624 (2005).

Moolten, S. E. Hamartial nature of the tuberous sclerosis complex and its bearing on the tumor problem. Arch. Intern. Med. 69, 589–623 (1942).

Osada, A., Iwabuchi, T., Kishimoto, J., Hamazaki, T. S. & Okochi, H. Long-term culture of mouse vibrissal dermal papilla cells and de novo hair follicle induction. Tissue Eng. 13, 975–982 (2007).

Way, S. W. et al. Loss of Tsc2 in radial glia models the brain pathology of tuberous sclerosis complex in the mouse. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 1252–1265 (2009).

Gan, B. et al. mTORC1-dependent and -independent regulation of stem cell renewal, differentiation, and mobilization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 19384–19389 (2008).

Roach, E. S., Gomez, M. R. & Northrup, H. Tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference: revised clinical diagnostic criteria. J. Child Neurol. 13, 624–628 (1998).

Kato, M. et al. Expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) by cultured angiofibroma stroma cells from patients with tuberous sclerosis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 18, 559–565 (1992).

Pfutzner, W. et al. Topical colchicine selection of keratinocytes transduced with the multidrug resistance gene (MDR1) can sustain and enhance transgene expression in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13096–13101 (2002).

Garlick, J. A. & Taichman, L. B. Fate of human keratinocytes during reepithelialization in an organotypic culture model. Lab. Invest. 70, 916–924 (1994).

Granville, C. A. et al. Identification of a highly effective rapamycin schedule that markedly reduces the size, multiplicity, and phenotypic progression of tobacco carcinogen-induced murine lung tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 2281–2289 (2007).

Perera, S. A. et al. HER2YVMA drives rapid development of adenosquamous lung tumors in mice that are sensitive to BIBW2992 and rapamycin combination therapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 474–479 (2009).

Crooks, D. M. et al. Molecular and genetic analysis of disseminated neoplastic cells in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 17462–17467 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Jonathan Vogel, with continuing gratitude for his mentorship. We thank Jonathan Vogel and Atsushi Terunuma for training in creating and grafting dermal–epidermal composites. We thank the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance and The LAM Foundation for patient referral, and Martha Vaughan, MD, for critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute, the Defense Medical Research and Development Program, and the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (T.N.D.). S.L. was supported by a Junior Investigator Award from the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance. J.M. was supported by the Intramural Research Program, NIH, NHLBI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. designed and conducted experiments, analysed data, prepared the figures and wrote the paper. R.L.T. conducted experiments, analysed data, prepared figures and edited the manuscript. J.-a.W. and S.R. conducted experiments and analysed data. T.-C.K. performed statistical analysis. L.S. analysed hair follicle morphology and edited the manuscript. J.M. provided patient and technical support and edited the manuscript. T.N.D. designed the study, analysed data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S4 and Supplementary Table S1. (PDF 1677 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Thangapazham, R., Wang, Ja. et al. Human TSC2-null fibroblast-like cells induce hair follicle neogenesis and hamartoma morphogenesis. Nat Commun 2, 235 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1236

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1236

This article is cited by

-

Pre-aggregation of scalp progenitor dermal and epidermal stem cells activates the WNT pathway and promotes hair follicle formation in in vitro and in vivo systems

Stem Cell Research & Therapy (2019)

-

Systematic analysis of somatic mutations driving cancer: uncovering functional protein regions in disease development

Biology Direct (2016)

-

Dissociated Human Dermal Papilla Cells Induce Hair Follicle Neogenesis in Grafted Dermal–Epidermal Composites

Journal of Investigative Dermatology (2014)

-

Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome and the skin

Familial Cancer (2013)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.