Abstract

Synthesis and reactivity of iron-dinitrogen complexes have been extensively studied, because the iron atom plays an important role in the industrial and biological nitrogen fixation. As a result, iron-catalyzed reduction of molecular dinitrogen into ammonia has recently been achieved. Here we show that an iron-dinitrogen complex bearing an anionic PNP-pincer ligand works as an effective catalyst towards the catalytic nitrogen fixation, where a mixture of ammonia and hydrazine is produced. In the present reaction system, molecular dinitrogen is catalytically and directly converted into hydrazine by using transition metal-dinitrogen complexes as catalysts. Because hydrazine is considered as a key intermediate in the nitrogen fixation in nitrogenase, the findings described in this paper provide an opportunity to elucidate the reaction mechanism in nitrogenase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

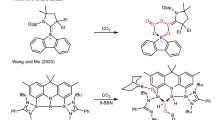

From a viewpoint of the function of molybdenum and iron atoms in nitrogenase, the development of the catalytic nitrogen fixation by using molybdenum- and iron-dinitrogen complexes as catalysts is one of the most important subjects in chemistry1. After the extensive study on the preparation and stoichiometric reactivity of various transition metal-dinitrogen complexes2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, the molybdenum-catalyzed nitrogen fixation by using molybdenum-dinitrogen complexes as catalysts under ambient reaction conditions has been achieved by Schrock and co-workers10,11 and our research group12,13,14,15. More recently, we have found the most efficient catalytic nitrogen fixation system by using molybdenum-nitride complexes bearing a tridentate triphosphine (PPP=bis(di-tert-butylphosphinoethyl)phenylphosphine) as a ligand, where up to 63 equiv of ammonia were produced based on the catalyst16.

In addition to the molybdenum-catalyzed nitrogen fixation, the iron-catalyzed reduction of molecular dinitrogen by using iron complexes under mild reaction conditions has recently been achieved because iron-catalyzed nitrogen fixation has also attracted attention from a viewpoint of the industrial nitrogen fixation (the Haber–Bosch process)17. In 2012, we found the first successful example of the iron-catalyzed reduction of molecular dinitrogen under ambient reaction conditions, where simple iron complexes such as [Fe(CO)5] and ferrocene derivatives worked as effective catalysts towards the formation of silylamine as an ammonia equivalent (up to 34 equiv based on the catalyst)18. In 2013, Peters and co-workers19 reported the iron-catalyzed direct reduction of molecular dinitriogen into ammonia under mild reaction conditions (1 atm at −78 °C), where a sophisticated iron-dinitrogen complex bearing a triphosphine-borane as a ligand worked as a catalyst (up to 7 equiv of ammonia based on the catalyst). More recently, Peters and co-workers20,21 have found the other iron-catalyzed nitrogen fixation system by using iron-complexes bearing a triphosphinealkyl ligand and two cyclic carbene ligands, where up to 4.6 equiv and 3.4 equiv of ammonia were produced based on the catalyst, respectively. However, the detailed reaction pathway has not yet been reported in all the iron-catalyzed nitrogen fixation systems22.

Based on our previous findings of the unique catalytic activity of molybdenum complexes bearing mer-tridentate ligands such as PNP′-pincer ligands (PNP′=2,6-bis(di-tert-butylphosphinomethyl)pyridine)12,13,14,15 and PPP16 ligand, we have designed iron-dinitrogen complexes bearing PNP′-pincer and PPP ligands as catalysts towards the iron-catalyzed nitrogen fixation. Although we have not yet succeeded in preparing the corresponding iron-dinitrogen complexes bearing PNP′-pincer and PPP ligands, we have been successful to prepare a similar iron-dinitrogen complex bearing an anionic PNP-pincer ligand (PNP=2,5-bis(di-tert-butylphosphinomethyl)pyrrolide)23,24,25 ([Fe(N2)(PNP)]: 1). As a result, an iron-dinitrogen complex as well as its precursors iron-hydride and -methyl complexes have been found to work as effective catalysts towards the catalytic nitrogen fixation under mild reaction conditions. Interestingly, a mixture of ammonia and hydrazine was obtained as nitrogenous products in the present reaction system. Herein, we report the catalytic reduction of molecular dinitrogen into ammonia and hydrazine by using the iron complexes bearing an anionic PNP-pincer ligand as catalysts.

Results

Preparation and characterization of iron complexes

The reaction of [FeCl2(thf)1.5] with lithium 2,5-bis(di-tert-butylphosphinomethyl)pyrrolide, generated from 2,5-bis(di-tert-butylphosphinomethyl)pyrrole and nBuLi, in toluene at room temperature for 14 h gave an iron-chloride complex bearing PNP ligand, [FeCl(PNP)], (2) in 85% yield (Fig. 1). Reduction of 2 with 1.1 equiv of KC8 as a reductant in tetrahydrofuran (THF) at room temperature for 13 h under an atmospheric pressure of dinitrogen afforded a paramagnetic iron(I)-dinitrogen complex 1 in 68% yield. Molecular structures of 1 and 2 were confirmed by X-ray analysis. ORTEP drawings of 1 and 2 are shown in Fig. 2a,b. Crystal structures of both 1 and 2 have a distorted square-planar geometry around the iron atom (the geometry index τ4=0.13 and τ4=0.11, respectively), where τ4=0.00 for a perfect square-planar and τ4=1.00 for a tetrahedral geometry26. A dinitrogen ligand coordinates to the iron atom in a terminal fashion with the Fe–N distance of 1.764(2) Å and the N–N distance of 1.134(2) Å. To our knowledge, only a few examples of square-planar iron complexes bearing a terminal dinitrogen ligand, except for iron-dinitrogen complexes bearing a 2,6-bis(imine)pyridine ligand27,28,29, have been reported until now.

The infrared (IR) spectrum of 1 in solid state (KBr) shows a strong vNN band at 1,964 cm−1 assignable to the terminal dinitrogen ligand. The complex 1 in a THF solution shows a vNN band at 1,966 cm−1, which is similar to that of 1 in a solid state. Cyclic voltammetry of 1 in THF with [NnBu4]PF6 as a supporting electrolyte revealed an irreversible reduction at −2.9 V versus ferrocene0/+ and an irreversible oxidation at −0.9 V (Supplementary Fig. 1). The reduction and oxidation can be assignable to Fe(0/I) and Fe(I/II) respectively. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) measurements were carried out at 10 and 296 K in toluene to investigate the spin state of the complex 1. The complex 1 shows a typical single EPR signal at room temperature, which is attributable to an S=1/2 system (Fig. 3). The g value (g=2.25) of 1 is largely deviated from that (2.0023) of a free electron. The width between extreme slope (140 G) of this EPR signal is much broader than that of conventional organic radicals, and therefore, any hyperfine structures could not be seen. The deviation of the g value and the broad bandwidth are characteristic features of EPR of metallocomplexes. In the EPR spectrum of 1 at 10 K (Supplementary Fig. 2), anisotropic EPR signals are observed at around g=2, but no EPR signal is seen at around g=4, suggesting S=1/2. Reproducible EPR signals at g=2.6 and 2.2 are attributable to the EPR of 1, which are similar to the previous EPR spectra observed for the low-spin iron(I) complexes with a square-planar geometry30. The complex 1 has a solution magnetic moment of 3.0±0.2 μB at 298 K. The measured magnetic moment is larger than spin-only value for an S=1/2 spin state (1.73 μB), but still within the range of the reported low-spin square-planar iron(I) compounds30,31. We consider that the large shift of the magnetic moment of 1 may be a result of the spin-orbit coupling.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the B3LYP-D3 level of theory32 have been carried out to discuss the ground spin state structure of 1. Optimized structures of 1 in the doublet and quartet states are depicted in Fig. 4, together with their selected geometric parameters. The result of the B3LYP-D3 calculations indicates that the ground spin state of 1 is doublet and the quartet state lies above 9.2 kcal mol−1. The Fe–N2 and N–N distances are calculated to be 1.779 and 1.135 Å in the doublet state and 1.987 and 1.127 Å in the quartet state, respectively, the former of which are close to those in the crystal structure of 1 shown in Fig. 2a. The geometry index τ4 in the doublet state (0.15) well reproduces a slightly distorted square-planar geometry around the iron atom in the crystal structure, while the quartet state structure has a larger value of τ4 (0.41). All the results strongly support the experimental finding that the ground spin state of 1 is doublet.

Reactions of 2 with KBHEt3 in THF and MeMgCl in Et2O at room temperature for 1 h afforded paramagnetic iron(II)-hydride and -methyl complexes, [FeH(PNP)] (3) and [FeMe(PNP)] (4), in 62 and 81% yields, respectively (Fig. 1). Molecular structures of 3 and 4 were confirmed by X-ray analysis. ORTEP drawings of 3 and 4 are shown in Fig. 2c,d. Crystal structures of both 3 and 4 have a distorted square-planar geometry around the iron atom (τ4=0.11 and τ4=0.12, respectively). The iron(II) complexes 2–4 have solution magnetic moments of 3.7±0.2, 3.6±0.2 and 3.8±0.2 μB at 296 K, respectively. The measured magnetic moments are larger than spin-only value for an S=1 spin state (2.83 μB), but still within the range of the reported intermediate-spin square-planar iron(II) compounds33,34,35. When the magnetic moments and the square-planar structures are taken into account, the complexes 2–4 can be assigned as intermediate-spin S=1 states. We consider that the spin-orbit coupling may contribute the large magnetic moments of 2–4.

Reactivity of iron complexes

At first, the catalytic reaction was carried out by using 1 as a catalyst under our reaction conditions, where CoCp2 and 2,6-lutidinium trifluoromethanesulfonate ([LutH]OTf) were used as a reductant and a proton source at room temperature12,13,14,15. However, no formation of ammonia was observed at all. Then, we investigated the catalytic reaction under the reaction conditions previously reported by Peters and co-workers19,20,21,22. Typical results are shown in Table 1. The reaction of an atmospheric pressure of dinitrogen with KC8 (40 equiv to 1) as a reductant and [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 (38 equiv to 1; ArF=3, 5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl) as a proton source in the presence of 1 as a catalyst in Et2O at −78 °C for 1 h gave 4.4 equiv of ammonia and 0.2 equiv of hydrazine based on the iron atom of the catalyst, respectively (Table 1, run 1). When the reaction was carried out at room temperature, the formation of ammonia and hydrazine was not observed, but only molecular dihydrogen (5.2 equiv) was produced. The use of larger amounts of both reductant and proton source increased the amounts of both ammonia and hydrazine, up to 10.9 equiv and 1.6 equiv, respectively (Table 1, runs 2 and 3). The largest amounts of ammonia and hydrazine (14.3 equiv of ammonia and 1.8 equiv of hydrazine) were obtained by using 200 equiv of KC8 and 184 equiv of [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 under the same reaction conditions (Table 1, run 4). Separately, we confirmed the direct conversion of molecular dinitrogen into ammonia and hydrazine using 15N2 gas instead of 14N2 gas. After the catalytic reaction, we could not identify any iron complexes and only the formation of free PNP-H was observed by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR).

The ratio of ammonia to hydrazine depends on the nature of solvents. When THF was used in place of Et2O, hydrazine was produced as a major product together with ammonia as a minor product based on the fixed N atom, where up to 2.4 equiv of hydrazine and 2.9 equiv of ammonia were produced based on the catalyst (Table 1, runs 5 and 6). Iron- and other transition metal-dinitrogen complexes have been reported to produce a stoichiometric amount of hydrazine on treatment of acids and reductants36,37,38,39. This result shows that the dinitrogen complex 1 works as a catalyst for the formation of hydrazine directly from dinitrogen. The use of much larger amounts of both reductant and proton source did not increase the amounts of both hydrazine and ammonia (Table 1, run 7). The formation of ammonia and hydrazine was not observed from the reaction in Et2O at −78 °C in the absence of iron-complexes as catalysts (Table 1, runs 8 and 9).

Interestingly, iron-hydride and -methyl complexes 3 and 4 also worked as effective catalysts under the same reaction conditions, where 3.0 equiv and 3.7 equiv of ammonia were produced based on the iron atom of the catalyst, respectively (Table 1, runs 10 and 11)19,20,40. We consider that the unique reactivity of iron-hydride complex 3 provides useful information to consider the reaction mechanism of nitrogenase because iron-hydride complexes are reported to play an important role as a key reactive intermediate in the catalytic cycle of nitrogenase1,41. Separately, we confirmed the protonation of 3 and 4 with 1 equiv of [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 in Et2O at room temperature and then the addition of 1 equiv of KC8 under N2 (1 atm) gave 1 together with molecular dihydrogen and methane, respectively. These results indicate that 3 and 4 are easily converted into 1 under the catalytic reaction conditions. Schrock and a coworker previously reported a similar phenomenon that protonation and reduction of a molybdenum-hydride complex bearing a triamideamine ligand under N2 (1 atm) gave the corresponding molybdenum-dinitrogen complex, which was worked as a catalyst for the formation of ammonia from molecular dinitrogen42. After the submission of the manuscript, Peters and co-workers43 have reported that an iron-hydride complex bearing a triphosphine-borane ligand was identified to be catalytically competent when it was solubilized, and also was identified to be a catalyst resting state, although Peters and co-workers reported that iron-hydride complexes did not work as catalysts in the previous papers19,20,40. On the other hand, only a stoichiometric amount of ammonia was formed when 2 was used as a catalyst (Table 1, run 12).

The formation of both ammonia and hydrazine is in sharp contrast to that in the Peters’ reaction systems19,20,21,22, where no formation of hydrazine was observed at all when iron-dinitrogen complexes bearing triphosphine-borane and -alkyl ligands, and two cyclic carbene ligands were used as catalysts. Separately, we confirmed that the partial reduction7,44,45,46,47 of hydrazine into ammonia in the presence of a catalytic amount of 4 proceeded in Et2O at −78 °C for 1 h (Supplementary Table 6). However, the use of THF in place of Et2O relatively inhibited the partial reduction of hydrazine into ammonia under the same reaction conditions. These results indicate that some iron-hydrazine complexes may be involved as key reactive intermediates in the transformation of hydrazine into ammonia. We consider that the result described in the present manuscript provides useful information on the elucidation of the reaction mechanism in nitrogenase because hydrazine may be formed as a key reactive intermediate in the biological nitrogen fixation1.

Discussion on the catalytic reaction pathway

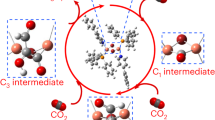

Based on the results of experimental and DFT calculations on the molybdenum-catalyzed nitrogen fixation under mild reaction conditions, we proposed that the transformation of molecular dinitrogen into ammonia under mild reaction conditions proceeds via hydrazide and nitride complexes (B and C, respectively) as key reactive intermediates as shown in Fig. 5a as a distal pathway12,13,14,15,16. However, the formation of hydrazine is not possible from a distal pathway. To explain the direct formation of hydrazine from molecular dinitrogen in the present iron system, we now propose an alternating pathway where the catalytic reaction proceeds via hydrazine complex (E) as a key reactive intermediate as shown in Fig. 5b19,22. In fact, the alternating pathway has been proposed for the stoichiometric formation of ammonia and hydrazine from iron-dinitrogen complexes based on the reactivity of isolated and generated intermediates36,37. In this alternating reaction pathway, dinitrogen complex (A) is converted into hydrazine complex (E) via sequential protonation and reduction. Hydrazine is formed by the ligand exchange of the coordinated hydrazine for molecular dinitrogen to regenerate the starting complex A. On the other hand, further protonation and reduction of hydrazine complex E give ammonia together with amide complex (F). Then, amide complex F is transformed into ammonia complex (D). Finally, the ligand exchange of the coordinated ammonia for molecular dinitrogen regenerates the starting complex A. As presented in the previous section, the ratio of ammonia to hydrazine depends on the nature of solvents. The ligand exchange of the coordinated hydrazine for molecular dinitrogen might proceed more smoothly in THF as solvent to give hydrazine as a major product. At the present stage, however, we can not exclude the possibility of ammonia formation via the distal reaction pathway. In addition, reduction of dinitrogen via a hybrid of the distal and the alternating pathways, where the hydrazide complex B was converted into hydrazine complex E on protonation and reduction, is also possible48.

To obtain information on reactive species in the present catalytic reaction by using 1, we carried out the protonation of 1 under the following reaction conditions. The protonation of iron-dinitrogen complex 1 with 1 equiv of [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 in Et2O at room temperature for 10 min gave the corresponding protonated complex (5) in 90% yield (Fig. 6). A vNN peak at 2,034 cm−1 assignable to the terminal dinitrogen ligand appeared at the IR spectrum of the protonated complex in solid state (KBr) although no vNH peak was observed. Based on the experimental result, we characterized 5 as iron-dinitrogen complex including the protonated pyrrole ring of PNP ligand. The result reveals that the first protonation at 1 may occur not at the coordinated dinitrogen ligand but at the pyrrole moiety in 1 (ref. 49). When we attempted to reduce 5 with 1 equiv of KC8 as a reductant in Et2O at room temperature for 10 min, a mixture of 1 and free PNP-H was observed in 38 and 27% yields by 1H NMR, respectively, together with the formation of 3 in 3% yield. Separately, we confirmed that the protonated iron-dinitrogen complex 5 has also a slightly lower catalytic activity towards the nitrogen fixation than 1 (Table 1, run 13). These experimental results indicate that the protonated iron-dinitrogen complex 5 is considered to be one of deactivated species in the present catalytic reaction.

DFT calculations on the reactivity of iron-dinitrogen complexes

To get further information on the reaction pathway, we have carried out DFT calculations on the first protonation of 1 with H+(OEt2)2, according to the experimental result shown in Fig. 6. The Natural Population Analysis (NPA) charges50 on the N2 ligand and the pyrrole moiety consisting of NC4H2 were calculated to be −0.20 and −0.59, respectively. Thus, the anionic PNP ligand in 1 should be considered as a possible site for the protonation by H+(OEt2)2. Figure 7a shows an electrostatic potential (ESP) map of 1, where reddish region in the mapped isosurface strongly attracts a positively charged species. The ESP map indicates that both the pyrrole moiety and the distal N atom of the N2 ligand are likely to accept a proton. Figure 7b describes energy profiles of proton transfer from H+(OEt2)2 to the pyrrole moiety of PNP (1 to II via TSII) and the N2 ligand (1 to III via TSIII). The protonation reactions require very low-activation energies, 6.8 kcal mol−1 for PNP and 7.3 kcal mol−1 for N2, both of which could be low enough to overcome even at 195 K. On the other hand, the protonation of a β-C atom of the pyrrole ring is highly exergonic by 17.4 kcal mol−1, while that of the N2 ligand is endergonic by 7.1 kcal mol−1. The shifts of vNN on protonation are +83 cm−1 for II and −302 cm−1 for III. The blue-shift of II is consistent with the observed shift (+70 cm−1) shown in Fig. 6, which can be ascribed to the protonation of the pyrrole ring of the PNP ligand49. All the results indicate that the protonation of 1 is not suitable for the formation of N–H bond of the coordinated N2 ligand.

(a) ESP maps (with the scale in atomic units) of 1 (left) and IV (right) on the 0.002 electrons/bohr3 isodensity surface, where reddish and bluish surfaces represent electron-rich and -poor regions, respectively. (b) Energy profiles of proton transfer from H+(OEt2)2 to the pyrrole ring of the PNP ligand (center to right) and the N2 ligand (center to left) in 1 and (c) those in V. Gibbs free energy changes (ΔGs) at 195 K are presented in kcal mol−1.

As described in the previous sections, the protonation of the coordinated dinitrogen ligand may not occur at 1. Based on the experimental result, we consider that reduction of 1 into the corresponding iron(0)-dinitrogen complexes precedes the protonation on the coordinated dinitrogen ligand of 1 in the catalytic reaction. In fact, Peters and co-workers19,20,21,22,51 reported that anionic low-valent dinitrogen complexes played essential roles in the catalytic activity for reduction of dinitrogen. Based on this assumption, we attempted to reduce 1 and 2 with an excess amount of KC8, K, Na and sodium naphtalenide as reductants in the presence or absence of crown ethers and cryptands under N2 (1 atm). The reaction of 2 with an excess amount of Na sand (5 equiv) in the presence of 1 equiv of 15-crown-5 in THF at room temperature for 15 h under an atmospheric pressure of dinitrogen gave 1 as a main product based on the IR measurement. However, recrystallization of the crude mixture afforded a few brown crystals. The preliminary result of X-ray analysis indicates the formation of an iron(0)-dinitrogen complex [Fe(PNP)(N2)][Na(15-crown-5)]. The obtained crystals showed a vNN peak at 1,831 cm−1 at the IR spectrum (KBr). The lower IR absorbance assignable to the terminal dinitrogen ligand indicates the possibility of formation of the reduced iron(0)-dinitrogen complex in the reaction mixture. Thus, based on the experimental result, we can consider the formation of reduced iron(0)-dinitrogen complexes under the catalytic reaction conditions.

To consider a reaction pathway that reduction of 1 precedes the protonation, we optimized the structure of an anion complex of 1, [Fe(PNP)(N2)]− (IV) (Fig. 4b). The ground spin state of IV is an open-shell singlet, where the Mulliken spin densities are assigned to Fe (+0.66) and N2 (−0.57). The closed-shell singlet and triplet states lies 2.3 and 5.1 kcal mol−1 above the open-shell singlet state, respectively. The N–N stretching in the open-shell singlet state of IV is calculated to be 1859, cm−1, which is close to the experimental value (1,831 cm−1). The calculated results would suggest the formation of anionic Fe(0)-dinitrogen complex IV from 1 in the presence of a suitable reductant. It is notable that the reduction of 1 significantly activates the N≡N bond of the N2 ligand. Reduction elongates the N–N distance by 0.030 Å (1.135 Å→1.165 Å) and increases negative charge on N2 by 0.26 (−0.20→−0.46), while a subtle change in the gross charge is observed in the pyrrole moiety (−0.59→−0.63). As shown in Fig. 7a, an ESP map of IV indicates that the N2 ligand in the anionic iron complex is expected to attract a proton more strongly compared with that in neutral complex 1.

We next examined the protonation of the N2 ligand and pyrrole moiety in IV, where a solvated potassium ion, K+(OEt2)2 is adopted as a counter cation of IV. In the lowest-energy structure of [Fe(PNP)N2][K(OEt2)2] (V), K+(OEt2)2 is located in the vicinity of the pyrrole moiety of the anionic iron complex (see more detail in the Supplementary Material). As shown in Fig. 7c, protonation of the N2 ligand in V yielding a diazenide complex VI via TSVI proceeds in a highly exergonic way (ΔG=−21.0 kcal mol−1) with a low-activation energy of 6.7 kcal mol−1. On the other hand, the positively charged K+(OEt2)2 is likely to prevent attack of H+(OEt2)2 to the pyrrole moiety. Protonation of a β-C atom of the pyrrole ring in V yielding VII via TSVII is also exergonic by 30.7 kcal mol−1 and requires an activation energy of 13.2 kcal mol−1, which is much higher than that for the protonation of N2. These results indicate that the reduction of 1 would provide a great advantage to the protonation of the N2 ligand, which is the first step towards the transformation of N2 into NH3. Further experimental and theoretical studies are necessary to elucidate the detailed reaction pathway.

Discussion

We have found that newly designed and prepared iron-dinitrogen, -hydride and –methyl complexes bearing an anionic PNP-pincer ligand worked as effective catalysts towards the iron-catalyzed reduction of molecular dinitrogen into ammonia and hydrazine under mild reaction conditions. Previously Shilov and co-workers52,53 reported that the reaction of dinitrogen with reductant in protic media in the presence of a catalytic amount of a molybdenum complex afforded hydrazine together with a small amount of ammonia. In this Shilov system, however, the detailed mechanism and the catalytically relevant species such as a dinitrogen complex have remained unclear52,53. In the present reaction system, we have achieved the first and clear-cut example of the catalytic direct formation of hydrazine from molecular dinitrogen under mild reaction conditions by using the well-defined transition metal-dinitrogen complexes as catalysts. We consider that the new findings described in this paper provide a new opportunity not only to design and develop more effective nitrogen fixations under mild reaction conditions by using transition metal-dinitrogen complexes as catalysts but also to elucidate the reaction mechanism in nitrogenase.

Methods

Preparation of [Fe(N2)(PNP)] (1)

A suspension of 2 (142 mg, 0.300 mmol) and KC8 (44.4 mg, 0.328 mmol) in THF (6 ml) was stirred at room temperature for 13 h under N2 (1 atm). The resultant dark red suspension was concentrated in vacuo. To the residue was added hexane (5 ml), and the solution was filtered through Celite, and the filter cake was washed with hexane (2 ml, 5 times). The combined filtrate was concentrated to ca. 3 ml and the solution was kept at −17 °C to give 1 as red crystals, which were collected by decantation, washed with a small amount of cold pentane and dried in vacuo (95.4 mg, 0.205 mmol, 68%). 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 3.3, −1.9, −15.1. Magnetic susceptibility (Evans’ method)54: μeff=3.0±0.2 μB in C6D6 at 296 K. IR (KBr, cm−1) 1,964 (s, vNN). IR (THF, cm−1) 1,966 (s, vNN). Anal. Calcd. for C22H42FeN3P2: C, 56.66; H, 9.08; N, 9.01. Found: C, 56.88; H, 9.10; N, 8.58.

Catalytic reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia

The catalytic reduction of molecular dinitrogen into ammonia and hydrazine was carried out according to a method similar to Peters’ procedure19,20,21,22. A typical experimental procedure using 1 is described below. In a 50-ml Schlenk were placed 1 (4.6 mg, 0.010 mmol), [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 (385 mg, 0.380 mmol), and KC8 (54.2 mg, 0.401 mmol). After the mixture was cooled at −196 °C, Et2O (5 ml) was added to the mixture by trap-to-trap distillation. The Schlenk flask was warmed to −78 °C and then was filled with N2 (1 atm). After stirring for 1 h at −78 °C, the mixture was warmed to room temperature and further stirred at room temperature for 20 min. The amount of dihydrogen of the catalytic reaction was determined by gas chromatography analysis. The reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the distillate was trapped in dilute H2SO4 solution (0.5 M, 10 ml). Potassium hydroxide aqueous solution (30 wt%; 5 ml) was added to the residue, and the mixture was distilled into another dilute H2SO4 solution (0.5 M, 10 ml). The amount of NH3 present in each of the H2SO4 solutions was determined by the indophenol method55. The amount of NH2NH2 present in each of the H2SO4 solutions was determined by the p-(dimethylamino)benzaldehyde method56.

Data availability

Detailed experimental procedures, characterization of compounds, Cartesian coordinates and the computational details can be found in the Supplementary Figs 1–11, Supplementary Tables 1–23 and Supplementary Methods. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC-1447087 (1), 1447088 (2), 1447089 (3) and 1447090 (4). These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. All other data are available from the authors on reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Kuriyama, S. et al. Catalytic transformation of dinitrogen into ammonia and hydrazine by iron-dinitrogen complexes bearing pincer ligand. Nat. Commun. 7:12181 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12181 (2016).

References

Hoffman, B. M., Lukoyanov, D., Yang, Z.-Y., Dean, D. R. & Seefeldt, L. C. Mechanism of nitrogen fixation by nitrogenase: the next stage. Chem. Rev. 114, 4041–4062 (2014).

Köthe, C. & Limberg, C. Late metal scaffolds that activate both, dinitrogen and reduced dinitrogen Species NxHy . Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 641, 18–30 (2015).

Khoenkhoen, N., de Bruin, B., Reek, J. N. H. & Dzik, W. I. Reactivity of Ddinitrogen bound to mid- and late-transition-metal centers. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 567–598 (2015).

Nishibayashi, Y. Recent progress in transition-metal-catalyzed reduction of molecular dinitrogen under ambient reaction conditions. Inorg. Chem. 54, 9234–9247 (2015).

Lee, Y. et al. Dinitrogen activation upon reduction of a triiron(II) complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 1499–1503 (2015).

Keane, A. J., Farrell, W. S., Yonke, B. L., Zavalij, P. Y. & Sita, L. R. Metal-mediated production of isocyanates, R3EN=C=O from dinitrogen, carbon dioxide, and R3ECl. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 10220–10224 (2015).

Creutz, S. E. & Peters, J. C. Diiron bridged-thiolate complexes that bind N2 at the FeIIFeII, FeIIFeI, and FeIFeI redox states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 7310–7313 (2015).

McSkimming, A. & Harman, W. H. A terminal N2 complex of high-spin iron(I) in a weak, trigonal ligand field. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 8940–8943 (2015).

Čorić, I., Mercado, B. Q., Bill, E., Vinyard, D. J. & Holland, P. L. Binding of dinitrogen to an iron–sulfur–carbon site. Nature 526, 96–99 (2015).

Yandulov, D. V. & Schrock, R. R. Catalytic reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia at a single molybdenum center. Science 301, 76–78 (2003).

Schrock, R. R. Catalytic reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia by molybdenum: theory versus experiment. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 47, 5512–5522 (2008).

Arashiba, K., Miyake, Y. & Nishibayashi, Y. A molybdenum complex bearing PNP-type pincer ligands leads to the catalytic reduction of dinitrogen into ammonia. Nat. Chem. 3, 120–125 (2011).

Tanaka, H. et al. Unique behaviour of dinitrogen-bridged dimolybdenum complexes bearing pincer ligand towards catalytic formation of ammonia. Nat. Commun. 5, 3737 (2014).

Kuriyama, S. et al. Catalytic formation of ammonia from molecular dinitrogen by use of dinitrogen-bridged dimolybdenum−dinitrogen complexes bearing PNP-pincer ligands: remarkable effect of substituent at PNP-pincer ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9719–9731 (2014).

Kuriyama, S. et al. Nitrogen fixation catalyzed by ferrocene substituted dinitrogen-bridged dimolybdenum–dinitrogen complexes: unique behavior of ferrocene moiety as redox active site. Chem. Sci. 6, 3940–3951 (2015).

Arashiba, K. et al. Catalytic reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia by use of molybdenum−nitride complexes bearing a tridentate triphosphine as Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 5666–5669 (2015).

Liu H. Ammonia Synthesis Catalysis: Innovation and Practice (ed. Liu, H.) World Scientific (2013).

Yuki, M. et al. Iron-catalysed transformation of molecular dinitrogen into silylamine under ambient conditions. Nat. Commun. 3, 1254 (2012).

Anderson, J. S., Rittle, J. & Peters, J. C. Catalytic conversion of nitrogen to ammonia by an iron model complex. Nature 501, 84–88 (2013).

Creutz, S. E. & Peters, J. C. Catalytic reduction of N2 to NH3 by an Fe−N2 complex featuring a C-atom anchor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 1105–1115 (2014).

Ung, G. & Peters, J. C. Low-temperature N2 binding to two-coordinate L2Fe0 enables reductive trapping of L2FeN2− and NH3 generation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 532–535 (2015).

Anderson, J. S. et al. Characterization of an Fe≡N−NH2 intermediate relevant to catalytic N2 reduction to NH3 . J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 7803–7809 (2015).

Venkanna, G. T., Arman, H. D. & Tonzetich, Z. J. Catalytic C−S cross-coupling reactions employing Ni complexes of pyrrole-based pincer ligands. ACS Catal. 4, 2941–2950 (2014).

Kreye, M. et al. Homolytic H2 cleavage by a mercury-bridged Ni(I) pincer complex [{(PNP)Ni}2{μ-Hg}]. Chem. Commun. 51, 2946–2949 (2015).

Levine, D. S., Tilley, T. D. & Anderson, R. A. C−H bond activations by monoanionic, PNP-supported scandium dialkyl complexes. Organometallics 34, 4647–4655 (2015).

Yang, L., Powell, D. R. & Houser, R. P. Structural variation in copper(I) complexes with pyridylmethylamide ligands: structural analysis with a new four-coordinate geometry index, τ4 . Dalton Trans. 955–964 (2007).

Scott, J., Vidyaratne, I., Korobkov, I., Gambarotta, S. & Budzelaar, P. H. M. Multiple pathways for dinitrogen activation during the reduction of an Fe bis(iminepyridine) complex. Inorg. Chem. 47, 896–911 (2008).

Stieber, S. C. E. et al. Bis(imino)pyridine iron dinitrogen compounds revisited: differences in electronic structure between four- and five-coordinate derivatives. Inorg. Chem. 51, 3770–3785 (2012).

Tondreau, A. M. et al. Oxidation and reduction of bis(imino)pyridine iron dinitrogen complexes: evidence for formation of a chelate trianion. Inorg. Chem. 52, 635–646 (2013).

Ohki, Y., Hoshino, R. & Tatsumi, K. N-heterocyclic carbene complexes of three- and four-coordinate Fe(I). Organometallics 35, 1368–1375 (2016).

Ouyang, Z. et al. Three- and four-coordinate homoleptic iron(I)-NHC complexes: synthesis and characterization. Organometallics 35, 1361–1367 (2016).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parameterization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Phys. Chem. 132, 154104 (2010).

Hawrelak, E. J. et al. Square planar versus tetrahedral geometry in four coordinate iron(II) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 44, 3103–3111 (2005).

Hashimoto, T. et al. Synthesis of bis(N-heterocyclic carbene) complexes of iron(II) and their application in hydrosilylation and transfer hydrogenation. Organometallics 31, 4474–4479 (2012).

Liu, Y. et al. Four-coordinate iron(II) diaryl compounds with monodentate N-heterocyclic carbene ligation: synthesis, characterization, and their tetrahedral-square planar isomerization in solution. Inorg. Chem. 54, 4752–4760 (2015).

Crossland, J. L. & Tyler, D. R. Iron–dinitrogen coordination chemistry: dinitrogen activation and reactivity. Coord. Chem. Rev. 254, 1883–1894 (2010).

Hazari, N. Homogeneous iron complexes for the conversion of dinitrogen into ammonia and hydrazine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 4044–4056 (2010).

Chatt, J., Dilworth, J. R. & Richards, R. L. Recent advances in the chemistry of nitrogen fixation. Chem. Rev. 78, 589–625 (1978).

Hidai, M. & Mizobe, Y. Recent advances in the chemistry of dinitrogen complexes. Chem. Rev. 95, 1115–1133 (1995).

Rittle, J., McCrory, C. C. L. & Peters, J. C. A 106-fold enhancement in N2-binding affinity of an Fe2(μ-H)2 core upon reduction to a mixed-valence FeIIFeI state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 13853–13862 (2014).

Igarashi, R. Y. et al. Trapping H− bound to the nitrogenase FeMo-Cofactor active site during H2 evolution: characterization by ENDOR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 6231–6241 (2005).

Yandulov, D. V. & Schrock, R. R. Studies relevant to catalytic reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia by molybdenum triamidoamine complexes. Inorg. Chem. 44, 1103–1117 (2005).

Del Castillo, T. J., Thompson, N. B. & Peters, J. C. A synthetic single-site Fe nitrogenase: high turnover, freeze-quench 57Fe Mössbauer data, and a hydride resting state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 5341–5350 (2016).

Chen, Y. et al. Nitrogenase model complexes [Cp*Fe(μ-SR1)2(μ-η2-R2N=NH)FeCp*] (R1=Me, Et; R2=Me, Ph; Cp*=η5-C5Me5): synthesis, structure, and catalytic N-N bond cleavage of hydrazines on diiron centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 15250–15251 (2008).

Yuki, M., Miyake, Y. & Nishibayashi, Y. Synthesis of sulfur- and nitrogen-bridged diiron complexes and catalytic behavior toward hydrazines. Organometallics 31, 2953–2956 (2012).

Umehara, K., Kuwata, S. & Ikariya, T. N−N bond cleavage of hydrazine with a multiproton-responsive pincer-type iron complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 6754–6757 (2013).

Chang, Y.-H., Chan, P.-M., Tsai, Y.-F., Lee, G.-H. & Hsu, H.-F. Catalytic reduction of hydrazine to ammonia by a mononuclear iron(II) complex on a tris(thiolato)phosphine platform. Inorg. Chem. 53, 664–666 (2014).

Rittle, J. & Peters, J. C. An Fe-N2 complex that generates hydrazine and ammonia via FeN=NH2: demonstrating a hybrid distal-to-alternating pathway for N2 reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 4243–4248 (2016).

Nadif, S. S., O’Reilly, M. E., Ghiviriga, I., Abboud, K. A. & Veige, A. S. Remote multiproton storage within a pyrrolide-pincer-type ligand. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 15138–15142 (2015).

Glendening, E. D. et al. NBO 5.9 Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin (2009) http://www.chem.wisc.edu/~nbo5.

Del Castillo, T. J., Thompson, N. B., Suess, D. L. M., Ung, G. & Peters, J. C. Evaluating molecular cobalt complexes for the conversion of N2 to NH3 . Inorg. Chem. 54, 9256–9262 (2015).

Bazhenova, T. A. & Shilov, A. E. Nitrogen fixation in solution. Coord. Chem. Rev. 144, 69–145 (1995).

Shilov, A. E. Catalytic reduction of molecular nitrogen in solutions. Russ. Chem. Bull. 52, 2555–2562 (2003).

Evans, D. F. Determination of the paramagnetic susceptibility of substances in solution by nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Chem. Soc. 2003–2005 (1959).

Weatherburn, M. W. Phenol-hypochlorite reaction for determination of ammonia. Anal. Chem. 39, 971–974 (1967).

Watt, G. W. & Chrisp, J. D. A spectrophotometric method for the determination of hydrazine. Anal. Chem. 24, 2006–2008 (1952).

Acknowledgements

The present project is supported by CREST, JST. We thank Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (nos. JP26288044, JP26105708, JP15K13687 and JP15H05798 to Y.N., no. JP24109014 to K.Y. and no. JP26888008 to H.T.) from JSPS and MEXT. S.K. is a recipient of the JSPS Predoctoral Fellowships for Young Scientists. We also thank the Research Hub for Advanced Nano Characterization at The University of Tokyo for X-ray analysis and EPR spectroscopy. Drs Toshiya Ideue and Masaki Nakano are thanked for the measurement of EPR spectroscopy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Y. and Y.N. directed and conceived this project. S.K., K.A. and K.N. conducted the experimental work. H.T. and Y.M. conducted the computational work. K.I. conducted the EPR measurements. All authors discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-11, Supplementary Tables 1-23, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 12171 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kuriyama, S., Arashiba, K., Nakajima, K. et al. Catalytic transformation of dinitrogen into ammonia and hydrazine by iron-dinitrogen complexes bearing pincer ligand. Nat Commun 7, 12181 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12181

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12181

This article is cited by

-

Near ambient N2 fixation on solid electrodes versus enzymes and homogeneous catalysts

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2023)

-

Cyclopentadienyl ring activation in organometallic chemistry and catalysis

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2023)

-

Catalytic production of ammonia from dinitrogen employing molybdenum complexes bearing N-heterocyclic carbene-based PCP-type pincer ligands

Nature Synthesis (2023)

-

N2 photofixation promoted by in situ photoinduced dynamic iodine vacancies at step edge in Bi5O7I nanotubes

Nano Research (2023)

-

Catalysts for nitrogen reduction to ammonia

Nature Catalysis (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.