Abstract

Interdecadal modes of tropical Pacific ocean-atmosphere circulation have a strong influence on global temperature, yet the extent to which these phenomena influence global climate on multicentury timescales is still poorly known. Here we present a 2,000-year, multiproxy reconstruction of western Pacific hydroclimate from two speleothem records for southeastern Indonesia. The composite record shows pronounced shifts in monsoon rainfall that are antiphased with precipitation records for East Asia and the central-eastern equatorial Pacific. These meridional and zonal patterns are best explained by a poleward expansion of the Australasian Intertropical Convergence Zone and weakening of the Pacific Walker circulation (PWC) between ∼1000 and 1500 CE Conversely, an equatorward contraction of the Intertropical Convergence Zone and strengthened PWC occurred between ∼1500 and 1900 CE. Our findings, together with climate model simulations, highlight the likelihood that century-scale variations in tropical Pacific climate modes can significantly modulate radiatively forced shifts in global temperature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deep atmospheric convection over the Indo-Pacific Warm Pool (IPWP) redistributes heat and moisture throughout the global climate system. The strength and location of IPWP convection is highly variable and strongly coupled to the Pacific Walker Circulation (PWC) and the associated modes of tropical climate variability, the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation. Changes in IPWP convection impact extra-tropical climate via meridional shifts in the average position of the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ), which influences the intensity of the Asian Summer Monsoon and the Australian-Indonesian Summer Monsoon (AISM; Supplementary Figs 1 and 2). Meridional and zonal variations of the Indo-Pacific climate system have very different impacts on Earth’s climate. Meridional shifts in the position of the ITCZ rapidly transmit hydroclimate perturbations across the hemispheres in response to changes in interhemispheric temperature gradients1. By contrast, zonal shifts in the PWC, which alter the trade wind fields and the location and strength of deep convection (both zonally and meridionally), extend the geographic reach of ENSO and contribute to global temperature changes2,3,4. Therefore, unravelling the history of deep atmospheric convection in the western equatorial Pacific region before instrumental measurements is critical for understanding the role of the tropics in modulating both regional and global climate variability.

Paleoclimate records spanning the last ∼2,000 years have highlighted the potential influence of Northern Hemisphere temperature changes in modulating Australasian atmospheric circulation via meridional shifts in the ITCZ5,6,7,8. However, the influence of zonal displacements in deep convection (associated with ENSO) in driving tropical climate is implicated by other studies9,10. As a result, there are different hypotheses regarding the precise drivers of tropical Pacific hydroclimate over the past millennium, and the relative importance of meridional forcing from the extratropics versus zonal ENSO-like shifts inherent to the tropics. To further examine these interactive climate systems, we have constructed a high-resolution multi-proxy hydroclimate record for southeast Indonesia spanning the last ∼2,000 years based on stalagmite oxygen (δ18O) and carbon (δ13C) isotopes, elemental ratios (Mg/Ca, Sr/Ca), and initial 234U/238U activity ratios. These data reveal substantial changes in AISM rainfall and deep atmospheric convection at the ascending limb of the PWC over the past two millennia. Comparison of our results with coupled general circulation model (CGCM) simulations reveal century-scale periods of divergence between the paleodata and model simulations, highlighting a deficiency in the models to capture the lower-frequency variability of the PWC. As such, the influence of the PWC to amplify the radiatively forced warming and cooling trends of the past millennium is limited in the models. These results have important implications for future projections of global temperatures because they show that state-of-the-art last millennium (AD 850–1850) and historical (AD 1850–2005) CGCM experiments may be underestimating the potential for low-frequency shifts in the tropical Pacific mean state to modulate Earth’s climate.

Results

Cave setting

The two stalagmites used in this study (LR06-B1 and LR06-B3) were collected from Liang Luar, an ∼1.7-km-long cave situated on the east Indonesian island of Flores (8° 32’N, 120° 26’E; 550 m above sea level; Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figs 1 and 2). Both specimens were located in a large chamber ∼600 m from the cave entrance and were actively growing at the time of collection in August 2006. Liang Luar resides close to the southerly limit of the austral summer ITCZ and most of the annual rainfall (∼70%) occurs during the AISM season (December to March)11.

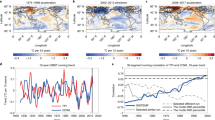

Field correlation map of annual rainfall and east equatorial Pacific sea surface temperatures. Correlation coefficients (r) were calculated between GPCP v2.2 precipitation (at each 1° × 1° grid point) and HadISST1 NINO3.4 SSTs (1979–2010). The coloured dots show the location of our study site and other paleoclimate records mentioned in the text. Yellow indicates relatively dry conditions during the Medieval Climate Anomaly5,6,9,44,46,48 (950–1250 CE), whereas cyan/purple indicates relatively wet conditions7,8/intense precipitation events10,47.

Stable isotope and trace element records

The hydroclimate record derived from stalagmites LR06-B1 and LR06-B3 is fixed in time by 35 uranium-thorium (U-Th) ages (Supplementary Figs 4–6) and spans the period 3 to 2005 CE (Common Era, Supplementary Table 1). All ages lie in stratigraphic order (within 2σ uncertainty) and have typical uncertainties of 1–3%. The age models for both records were first calculated using a Bayesian–Monte Carlo approach12 and then refined using the intra-site correlation age modelling programme (iscam)13 written in MATLAB (see the Methods for details). The age models give an average growth rate of ∼125–135 μm per year for both stalagmites.

The δ18O and δ13C records are based on 1,157 measurements performed on calcite powders micromilled along the central growth axes of LR06-B1 and LR06-B3. The Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca ratios in stalagmite LR06-B1, previously presented in Griffiths et al.14, were analysed on H3PO4 residues following calcite dissolution for stable isotope analysis. The strong degree of replication between the two stable isotope profiles (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 2), along with ‘Hendy’ screening tests15 conducted on these specimens11, rules out significant disruption of the records by kinetic isotope fractionation effects.

Comparison of stalagmites LR06-B3 and LR06-B1 (a) δ18O, (b) δ13C, (c) Mg/Ca (cyan) and Sr/Ca (red), (d) LLPC1 (black line) and [234U/238U]i (purple dots: LR06-B3; blue dots: LR06-B1; dashed line: cubic spline fitted to the data) and (e) LLPC2. We interpret higher (lower) values in LLPC1 and [234U/238U]i in d to reflect drier (wetter) conditions. Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca records were previously reported in Griffiths et al.14. The PC factor loadings for each time series of PC1 and PC2 are shown in parentheses. PC1 accounts for 50% of the variance and PC2 accounts for 20%. Colour-coded symbols along the bottom indicate U-Th ages (purple: LR06-B3; blue: LR06-B1) and their associated 2σ uncertainties. The grey shading in d,e indicates the 95% bootstrap confidence interval. Vertical bars indicate the approximate timing of the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA; yellow), Little Ice Age (LIA; blue) and Current Warm Period (CWP; pink) in Flores, defined by decreased AISM rainfall during the MCA and CWP, and increased AISM rainfall during the LIA.

The δ18O values for LR06-B1 and LR06-B3 range from −5.6 to −6.9‰ and average −6.2‰ between 1 and 2005 CE, whereas the δ13C values range from −7.8 to −13.4‰ and average −10.8‰. Broadly speaking, the δ18O and δ13C records display multidecadal- to centennial-scale oscillations with generally lower values from ∼500 to 900 CE and ∼1300 to 1600 CE, and generally higher values from ∼1000 to 1300 CE The Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca profiles show patterns similar to the stable isotopes over the last millennium, with generally higher values from ∼1000 to 1300 CE followed by a trend to lower values until ∼1600 CE Between ∼1600 CE and ∼2004 values have generally increased, signifying an overall reduction in rainfall over this period with the trend being most significant during the twentieth century.

Interpretation of the stalagmite δ18O record

The seasonal pattern of monsoon rainfall at Liang Luar is reflected in the δ18O of precipitation (δ18Op), with summer rainfall (DJFM) ∼6–7‰ lighter than its winter monsoon (JJA) counterpart11. Hence, a change in the fraction of the year dominated by the summer monsoon (that is, change in seasonality), or a shift in monsoon rainfall amount in summer, should have a significant impact on the average annual δ18O value. The strong relationship between Indonesian rainfall amount and δ18Op has been identified in modern isotope studies11 and CGCM simulations of modern16,17 and past18 hydroclimates in Indonesia. Model simulations of precipitation δ18Op using the National Center for Environmental Prediction (NCEP)/National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) nudged IsoGSM17 for the grid point closest to Liang Luar reveal a significant correlation with sea-surface temperatures (SSTs) over the NINO3.4 region and, to a lesser extent, in the western Indian Ocean; this pattern is similar to the observed pattern of rainfall amount at Liang Luar (Supplementary Fig. 3). Moreover, comparison of Liang Luar IsoGSM δ18Op with observed rainfall amount, outgoing longwave radiation and zonal 850 mb winds reveals that δ18Op is strongly influenced by western Pacific rainfall variability, which is governed by the strength of the AISM, the position of the ITCZ and ENSO (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Based on observed and modelled precipitation δ18O systematics, we interpret variations in the Flores speleothem δ18O records to primarily reflect regional rainfall amount. However, on relatively short timescales (centuries), other factors may affect stalagmite δ18O, such as changes in cave temperature (due to shifts in regional SSTs), the δ18O of surface seawater5, the proportion of summer- and winter-sourced moisture11 and multidecadal changes in the relationship between δ18Op and ocean-atmosphere climate modes, such as ENSO19 and the Indian Ocean Zonal Mode20. In addition, mixing of meteoric water in the soil-karst overburden (∼50–100 m) above Liang Luar reduces the amplitude of the highest frequencies21 (for example, seasonal-annual variations), which likely varies with time. Therefore, some of the observed variability may be an artefact of filtering through the karst network. However, given the amount of cave recharge through the epikarst each monsoon season, it is likely that the δ18O of the cave drip-water represents decadal (if not multi-year) shifts in precipitation.

A composite multi-proxy stalagmite record

To constrain the Liang Luar paleomonsoon record, we compare the stalagmite δ18O with the contemporaneous carbon isotope (δ13C), Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca ratios, which primarily reflect Liang Luar karst hydrology14,22. Recent geochemical modelling of the soil-karst system above Liang Luar demonstrated that the δ13C in the late Holocene section of stalagmite LR06-B1 was controlled by the degree of prior calcite precipitation (PCP)22 in the epikarst ‘upstream’ of the stalagmite. Under this process, periods of reduced recharge result in partial dewatering of the karst fracture system overlying the cave, which causes a greater proportion of the CO2 degassing to occur before the drips reach the growing stalagmite23. The waters therefore become supersaturated in CaCO3 before their emergence in the cave, causing upstream (prior) calcite precipitation in fractures and on stalactite tips. In the case of δ13C, carbonate precipitation results in a higher stalagmite δ13C owing to the greater removal of 12CO2 during the degassing process24,25. The opposite occurs during wetter intervals25 (Fig. 2). Additional climate-related factors may have influenced the stalagmite δ13C, such as changes in the ratio of C3:C4 plants, soil respiration rates, contributions from atmospheric CO2 (refs 26, 27) and the relative contribution of bedrock carbon due to changes in open- versus closed-system dissolution22. However, these factors are all susceptible to hydrological changes and fluctuate in the same sense as PCP (that is, higher δ13C values indicate drier conditions). Therefore, regardless of their relative contributions to the carbon-isotope mass balance, shifts in stalagmite δ13C are inextricably linked to hydroclimate variations at this site.

Additional support for a PCP signal is provided by the pattern of Sr/Ca and Mg/Ca changes over the last 2,000 years (Supplementary Fig. 8). Covariation between these two ratios is diagnostic of a hydrologic control23,28: increases in both indicate drier conditions because the preferential loss of Ca2+ from solution (relative to both Mg2+ and Sr2+) in the percolation waters during PCP raises the Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca of the drip waters. This is transmitted to the stalagmite as higher Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca. During wetter intervals, PCP is either reduced or absent, leading to lower Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca in the stalagmite23. The significant correlation between δ13C and both trace element ratios provides even more compelling evidence of hydroclimate-driven changes in the degree of PCP over the last 2,000 years (Supplementary Fig. 8). It not only reinforces the similar findings recorded in Liang Luar for the entire Holocene14, but is in good agreement with previous studies of short-term (seasonal to annual)26 and long-term (century to orbital)29 hydroclimate change.

To effectively combine the climate proxies for stalagmites LR06-B1 and LR06-B3 into one composite hydroclimate record, we conducted an unrotated principal component (PC) analysis on the six individual stable isotope and trace element time series. The leading PC (from here referred to as ‘LLPC1’) represents the dominant hydrologic signal embedded in the records30 (Fig. 2). The stalagmite δ18O does not significantly load on LLPC1 indicating that the processes important in altering precipitation δ18O (vapour transport, oceanic source and regional temperatures)31 may not strongly affect the amount of moisture at the cave site. These additional effects on δ18Op are best captured in the second PC (Fig. 2). Therefore, at century timescales, δ18Op probably reflects the over-riding influence of large-scale ocean-atmospheric processes that do not strongly affect the total amount of precipitation at the site32. These findings highlight the importance of utilizing multiple speleothem geochemical tracers to reconstruct tropical hydroclimate during the relatively stable background climate state of the last two millennia.

Additional evidence to support LLPC1 as a hydrologic proxy is provided by initial uranium isotope activity ratios ([234U/238U]i) in the Liang Luar stalagmites (Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 2d). Holocene [234U/238U]i ratios of LR06-B1 and LR06-B3 reflect the extent of dissolution related to the rate of groundwater movement in the epikarst of Liang Luar14,30. The [234U/238U]i values increase during drier periods when relatively slow-moving percolation waters (in approximately chemical equilibrium with the host rock) preferentially remove 234U (produced by alpha recoil or preferential leaching and loosely bound in limestone bedrock)33. In contrast, during wetter periods, the more rapid traverse of the percolation water through the karst network can result in greater dissolution rates causing both U isotopes to be leached approximately equally from the host rock. This can lead to relatively low [234U/238U]i values in a stalagmite. Comparison of the [234U/238U]i values with LLPC1 reveals similar multicentury trends over the past 2,000 years.

A final confirmation that LLPC1 reflects a regional hydroclimate signal over the western Pacific is provided by the significant correlation with other paleohydrologic records from the region, including a seawater δ18O record5 (r=0.5, 50-year smoothed, significant at the 99% level) and a leaf wax δD record6 (r=0.28, 50-year smoothed, significant at the 95% level) from marine sediment cores drilled in the Makassar Strait immediately west of Sulawesi (Fig. 1).

Meridional shifts in the Australasian ITCZ

The LLPC1 record exhibits pronounced century-scale excursions, with positive values (drier climate) at ∼0–400 CE, ∼1000–1400 CE and ∼1900–2004 CE, and negative excursions (wetter climate) at ∼400–1000 CE and ∼1400–1900 CE (Fig. 3). The dry period at around the turn of the last millennium coincides with the approximate timing of the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA; ∼950–1250 CE)34. This ∼400-year reduction in AISM rainfall begins to recover in strength at around 1300, and by 1500 is above average during the Little Ice Age (LIA). Maximum rainfall in Flores at ∼1600 CE, among the wettest periods of the past 2,000 years, is synchronous (within dating uncertainty) with peak cooling in the Northern Hemisphere34 and maximum ice discharge in the North Atlantic35 (Fig. 3a).

(a) North Atlantic drift ice index35. (b) Stalagmite δ18O record from Wanxiang Cave, China7. (c) Mean grain size (MGS) of lake core DY6 from Dongdao Island in the South China Sea (SCS)9. (d) Northwest Australian flood events as recorded in a stalagmite from KNI-51 cave42. (e) Total solar irradiance reconstructed from cosmogenic nuclides43. The black line and grey shading in all panels shows the LLPC1 record and corresponding 95% bootstrap confidence interval. The y axis for the LLPC1 record is oriented to show a weaker AISM with warmer North Atlantic temperatures. Positions of the U-Th dates (with 2σ uncertainties) for both stalagmites are shown along the bottom. Vertical bars indicate the approximate timing of the MCA (yellow), LIA (blue) and CWP (pink) in Flores, defined by decreased AISM rainfall during the MCA and CWP, and increased AISM rainfall during the LIA.

Comparison of the Flores LLPC1 record with subtropical paleomonsoon records from China7 (Fig. 3b) reveals synchronous (antiphased) multicentury fluctuations in monsoon rainfall across the hemispheres. The cross-equatorial antiphase relationship is consistent with both CGCMs36 and glacial paleoclimate records37,38, showing that cooling of the high northern latitudes increases the interhemispheric thermal gradient, displacing the Australasian ITCZ southward. However, zonal changes in the PWC are also known to strongly influence western Pacific hydroclimate39, and are thought to be a significant driver of low-latitude climate change on century scales40. Indeed, an in-phase relationship between LLPC1 and paleohydrologic records from the South China Sea9 (Fig. 3c) challenges the paradigm of regional north–south ITCZ migrations as the primary control of lower-frequency monsoon shifts in the western Pacific over the past millennium. Critically, a recent synthesis of paleohydrologic records for the Australasian monsoon region41, including a new northwest Australian flood record42 (Fig. 3d), demonstrated that, rather than moving southward during the LIA, the latitudinal range of monsoon-ITCZ migration probably contracted equatorward, perhaps in response to lower solar irradiance43 (Fig. 3e).

Zonal teleconnections via the PWC

Evidence for a potential link between the PWC and multi-century changes in western Pacific rainfall is provided by the inverse relationship between the AISM5,6 and rainfall in the central8-eastern10,44,45,46,47,48 equatorial Pacific (Fig. 4) over the past millennium. Specifically, the western Pacific and Peruvian Andes (Fig. 4a–e) were generally wetter during the LIA, whereas the central and eastern equatorial Pacific (EEP) experienced drier conditions (Fig. 4f) or reduced heavy precipitation events (Fig. 4g,h), similar to La Niña events today when the PWC strengthens (Fig. 1). Conversely, drier conditions in Indonesia and Peru (along with Panama48) during the MCA were matched by wetter conditions in the central and EEP, signifying a more ‘El Niño-like’ mean state. Wavelet-transform analysis of the Flores LLPC1 shows significant multidecadal to centennial periodicities in the AISM record (Supplementary Fig. 8) that have also been identified in reconstructions of ENSO amplitude from North American tree rings49 and NINO3.4 SSTs40 (Supplementary Fig. 9).

(a) Flores LLPC1 record. (b) Marine foraminifera δ18Osw (ref. 5) and (c) terrestrial δDleaf-wax (ref. 6) records recovered from marine sediment cores located in the Makassar Strait on the Sulawesi margin. (d) δ18O of lake sediment calcite in Laguna Pumacocha in the central Peruvian Andes (proxy for the strength of the South American summer monsoon)44. (e) Speleothem δ18O record from Cascayunga cave in northeast Peru46. (f) δDleaf-wax record from Washington Island in the central equatorial Pacific8. (g) Red-colour intensity from Laguna Pallcacocha, southern Ecuador47. (h) Percent sand in El Junco lake, Galápagos Islands10. For clarity, all records have been converted to standard (z) scores with blue indicating wetter conditions (a–f) or heavier precipitation events (g–h) and vice versa for red. Vertical bars indicate the approximate timing of the MCA (yellow), LIA (blue) and CWP (pink) in Flores.

The multi-proxy record of eastern Indonesian hydroclimate presented here (LLPC1) lends support to a LIA characterized by a stronger PWC, whereas the LLPC1 shows drier conditions during the MCA, indicating a weaker PWC. These findings are compatible with the ITCZ expansion (LIA)/contraction (MCA) hypothesis of Yan et al.41 The temporal changes in zonal precipitation across the equatorial Pacific5,6,8,9,10,40 are also consistent with some terrestrial reconstructions of ENSO40,45,50 activity (Fig. 5), which show strengthening of the PWC during the LIA, and weakening during the MCA. These findings run counter to inferences from some SST-based ENSO reconstructions from the western5,51, central52 and EEP53, which suggest that the tropical Pacific was characterized by ‘La Niña-like’ conditions during the MCA compared with the LIA. However, there is still no consensus on the marine paleo-ENSO signals; a recent reconstruction of EEP SSTs54 indicates that the MCA was marked by relatively warm SSTs in the EEP, contradicting the findings of earlier studies.

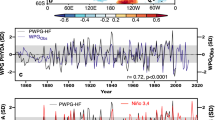

Panels a–d show paleoclimate records34,40,50,59,60 and e–h show CCSM4 LM+hist CGCM simulations. Comparison of Flores precipitation (a,e), SOI (b,f), NINO3.4 SSTs (c,g) and land temperatures (red: NH; blue: global; d,h). The records have been smoothed with a 50-year (thick coloured lines) and 7-year (thin grey lines) loess filter. All time series were converted to standard (z) scores to facilitate comparison of proxy reconstructions with model simulations. Vertical bars indicate the approximate timing of the MCA (yellow), LIA (blue) and CWP (pink) in Flores.

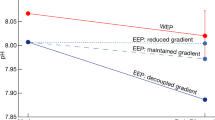

Theoretical and physical models of the PWC are also not entirely consistent within the context of Indo-Pacific climate change during the past millennium. Modern dynamical studies suggest that under warmer conditions, the PWC should weaken55,56, and at least one paleoclimate study supports the inference of a stronger PWC during the LIA41. On the other hand, the ‘ocean dynamical thermostat’ mechanism57 supports a potential weakening of the PWC during the LIA. Modern observations do not yet distinguish the PWC’s response to global warming. Yan et al.41 recently noted that there are numerous interacting components that may contribute to the discrepancies among paleoclimate records: (i) misinterpretation of SST or hydrological signals with respect to meridional versus zonal changes in ocean-atmosphere circulation; (ii) decoupling of ocean and atmospheric processes in response to different forcings over century time scales and (iii) the interacting influence of multidecadal climate modes (for example, Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation) with ENSO, which are difficult to identify in the proxy records that originate from outside these system’ centres of action.

Palaeoclimate proxy-model comparisons

To explore the potential role of multidecadal- to century-scale changes in the PWC on global climate variability, we examined the relationship between Flores rainfall, NINO3.4 SSTs and the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) with similar indices in CGCM simulations (Fig. 5). To do so, we employed the Paleoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project Phase 3 (PMIP3) last millennium (LM; 850–1849 CE) and historical (1850–2005 CE) CGCM runs from the US NCAR CCSM4 (ref. 58) model. The CCSM4 model was employed because its simulation of the modern hydroclimate dynamics of east Indonesia compares well with observations. Importantly, model preindustrial control runs (500-year-long) accurately simulate the influence of ENSO on rainfall variability around Flores (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Table 3). Although the association of SST with rainfall is somewhat stronger and more widespread in models compared with observations, the regional pattern of SST is consistent. The dominant influence of ENSO on east Indonesian rainfall is also apparent for the LM and historical (LM+hist; 850–2005 CE) simulations (Supplementary Table 3), although the correlation is not as strong as for the preindustrial control runs.

If variations in global temperatures over the LM were amplified by decadal to multidecadal variations in the tropical Pacific, as is the case during the instrumental period2,3,4, then model skill in the tropical Indo-Pacific region is clearly important for projecting future climate change. Therefore, we compared Flores precipitation, the SOI and NINO3.4 SSTs captured in the proxy records40,50 (Fig. 5a–c) with the same indices in the LM+hist CCSM4 simulations (Fig. 5e–g). In the LM+hist CGCM experiments, the variance in Pacific SST and Indonesian rainfall is concentrated at interannual/decadal time scales, whereas the paleoclimate record for Indonesia exhibits strongest variance at multidecadal to centennial periodicities (Supplementary Fig. 8). However, the coherent patterns of lower-frequency variability evident in the network of western Pacific hydroclimate records suggest that the data-model mismatch likely stems from model deficiencies with respect to century-scale variations in the PWC (Fig. 5b,c,f,g), particularly during the MCA and LIA. Consequently, the models may be underestimating the magnitude and duration of reconstructed global59 and hemispheric34,60 Medieval warming, and the persistent LIA cooling between ∼1400 and ∼1850 CE (Fig. 5d,h).

Our results highlight significant discrepancies between the proxy records and model simulations for the past millennium. Critically, these discrepancies coincide with century-scale anomalies in the strength of the PWC. We cannot rule out the possibility that some of the low-frequency Pacific variability was a forced response to variable solar intensity36 and changing teleconnections to higher latitudes61 that are not simulated by the models, or that non-climatic processes have influenced the proxies62. However, of particular importance is that the paleodata-model mismatch supports the possibility that unforced, low-frequency internal climate variability (that is difficult for models to simulate) was responsible for at least some of the global temperature change of the past millennium62,63.

Discussion

The broad east–west antiphasing of Pacific hydroclimate during the past millennium, and clear connections with higher-latitude climates, suggests the deep tropics may have played a more active role in global climate change than previously assumed. Indeed, Northern and Southern Hemisphere temperature reconstructions34,60 (Fig. 5d) reveal symmetrical shifts in air-temperature over the past millennium (particularly during the LIA), suggesting that changes in the interhemispheric temperature gradient, and north–south shifts in the ITCZ, cannot explain the tropical precipitation variability evident in the proxy records. Instead, it is more likely that the LIA global cooling was initiated by a decline in solar irradiance (and lower atmospheric CO2 and potentially increased volcanic activity)60 and amplified by the strengthened PWC that occurred in parallel with a latitudinal contraction of the ITCZ41. Although it would be premature to suggest that LIA cooling was triggered by century-scale shifts in the tropical mean state, a stronger PWC during the LIA may have intensified broad-scale cooling already underway, and a weaker PWC during the MCA could have acted to warm the planet.

Our findings have significant implications for projections of decadal-scale changes in tropical atmospheric convection and global temperatures. For example, from the beginning of this century until recently, the tropical Pacific was locked into a negative Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation phase (that is, low-frequency La Niña-like pattern) in association with increased Walker and Hadley circulation winds and eastern Pacific cooling2,3. The La Niña-like pattern is thought to be a factor contributing to the recent so-called ‘warming hiatus’2,3 and earlier twentieth century cool and warm decades4. Therefore, our analysis of multicentury hydroclimate variability suggests that projections of tropical rainfall patterns, and global temperature extremes, will remain uncertain until paleoclimate records and models consistently capture the lower-frequency variability, and associated feedbacks, in the tropical Pacific.

Methods

230Th dating and age models

A total of 35 pieces of calcite, each weighing ∼50–300 mg, were extracted from the central growth axis of stalagmites LR06-B1 and LR06-B3. Samples were removed using a carbide dental bur fitted to an air drill. 230Th/234U age determinations were conducted on both a thermal ionisation mass spectrometer and a multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICPMS; Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figs 4 and 5). Thermal ionisation mass spectrometer analyses were carried out at the University of Queensland using a Fisons VG Sector 54–30 mass spectrometer equipped with a WARP filter and an ion counting Daly detector, as described by Yu et al.64 The MC-ICPMS U-Th analyses were conducted on two separate Nu-Instruments Nu Plasma mass spectrometers housed at the University of Melbourne and the University of Queensland. For a description of the MC-ICPMS methods employed at the University of Melbourne, refer to study by Hellstrom65. The methods employed at the University of Queensland are outlined in Zhou et al.66. All samples were corrected for initial 230Th using an initial 230Th/232Th value of 3.4±1.7. The initial 230Th/232Th value was determined by the methods described in the study by Hellstrom65. Corrected ages were calculated using half-lives specified in Cheng et al.67

The age models for LR06-B1 and LR06-B3 were first calculated using a Bayesian–Monte Carlo approach12, producing two δ18O time series that display a good level of coherence (Fig. 2 and Supplementary 7), despite the minor discrepancy between the two isotopic profiles during the period ∼700–1000 CE, which we attribute to slight differences in the resolution of U-Th dates through this interval (see Supplementary Figs 4 and 7 for details). Given this degree of replication, we refined the age models using iscam13 (that is, Intra-Site Correlation Age Modelling) with a prescribed point-wise linear interpolation scheme between adjacent U-Th ages. This novel age-model algorithm finds the best correlation between the proxy records for two (or more) neighbouring dated stalagmites (highest r value of 0.73 between LR06-B1 and LR06-B3) using a Monte Carlo approach (100,000 simulations using a 100-year smoothing), and then calculates the most probable age model for both records based on the calculated correlation coefficients. Because the two stalagmites were collected from the same cave chamber, we assume that the geochemical excursions preserved in the overlapping sections of both records reflect a real climate signal, and that minor discrepancies between the two are likely due to the uncertainties in the U-Th dates and slight differences in calcite stratigraphy. Significance levels were calculated against a red-noise background from 2,000 pairs of artificially simulated first-order autoregressive time series (AR1). The iscam age model provides a number of advantages to simple linear interpolation, which include: (i) quantitative assessment of whether the isotopic signals from multiple stalagmites have a common signal within age error; (ii) linking climatic proxies from multiple samples to construct a composite record and (iii) significant reduction of age uncertainty within overlapping time intervals through the enlargement of the signal-to-noise ratio.

Stable isotope analysis

The oxygen (δ18O) and carbon (δ13C) isotope profiles for stalagmite LR06-B1 were established from 632 calcite powders micromilled along the central growth axis. The top 74 mm (that is, top of stalagmite down to a depth of 74 mm) of LR06-B1, which represents the ∼1172–2004 CE period of growth, was micromilled at 0.15 mm increments (∼1- to 4-year resolution). 30–70 μg of sample powders were analysed on a Thermo Finnigan Kiel IV carbonate device coupled with a Delta V Plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer at the University of California, Irvine (n=458 samples). Measurement precision (1σ) for the NBS-19 standard material was ±0.06‰ for δ18O and 0.03‰ for δ13C. The lower section of LR06-B1, representing ∼1–1172 CE period of growth (that is, depth between 74 and 246 mm from the top), was drilled at 1 mm increments (∼7- to 10-year resolution). The δ18O and δ13C for these lower-resolution samples was measured on ∼1 mg powders using a GV Instruments GV2003 continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer at the University of Newcastle, Australia (n=174 samples). The precision (1σ) of in-run measurements of the standard material (a Carrara Marble called New1) was ±0.08‰. These lower-resolution samples were previously reported in Griffiths et al.11

The δ18O and δ13C profiles for LR06-B3 were established from 525 calcite powders micromilled at 0.5 mm increments along the growth axis. The isotope measurements were performed at the University of Arizona on a Micromass Optima dual-inlet stable isotope ratio mass spectrometer with an automated carbonate preparation system. The precision (1σ) for in-run measurements (n=113) of laboratory standard material Luxor was ±0.07‰ for δ18O and δ13C. All results are expressed as the deviation in per mil (‰) between the sample and Vienna Peedee Belemnite standard using the delta notation.

Trace element analysis

The Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca ratios in stalagmite LR06-B1 were analysed on H3PO4 residues after calcite dissolution for stable isotope analysis. The samples were analysed for Mg, Sr and Ca on a Varian Liberty 4,000 inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer. Molar concentrations of the elements were calculated from inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer intensities using four internal working standards of known concentration and a blank, with concentrations expressed as ratios to Ca. Acid blank corrections were applied to both sample and standard data before conversion of the data to ratios. The relative standard deviation of replicate standards of Ca, Mg and Sr was 1.5%, 1.6% and 2.4%, respectively. These data were previously published in Griffiths et al.14,22,30

PC analysis

The speleothem hydroclimate record was constructed using the δ18O and δ13C for stalagmites LR06-B1 and LR06-B3, and trace elements (Mg/Ca, Sr/Ca) for LR06-B1. Due to the average resolution among all records being ∼5 years, we linearly interpolated each proxy record to a common 5-year temporal resolution before analysis. To extract the dominant climate signal embedded within the stable isotope and trace element records, we performed an unrotated PC analysis on the six profiles, where the leading PC (explains 50% of the variance) represents the dominant hydrologic signal common to all individual time series. Because other factors besides rainfall can affect the δ18O (for example, cave temperature, changes in ratio of summer versus winter moisture delivery) and δ13C (for example, above-cave vegetation, soil productivity, cave ventilation) and also the trace elements (for example, cave temperature, speleothem growth rate), this method has proven useful in isolating the dominant hydrologic signal from other potential influences30. However, the δ18O time series load weakly on PC1, and load much more strongly on PC2. This suggests that factors in addition to local rainfall amount likely influenced the speleothem δ18O. Confidence intervals (95%) for the PCs were calculated using bias-corrected and accelerated nonparametric bootstrap technique performed in MATLAB.

General circulation modelling

To assess the long-term dynamical influence of the Walker circulation on IPWP convection, and NH and global temperatures, we used the PMIP3 LM (850–1849 CE) and historical (1850–2005 CE) CGCM runs from the US NCAR CCSM4 (ref. 58) model. The skill of the CGCMs in simulating the observed (that is, instrumental) ENSO influence on western Pacific hydroclimate was demonstrated by comparing field correlation maps between east Indonesian rainfall (annual precipitation averaged over a gridbox encompassing the area 12°–6° S and 110°–125° E) and SSTs in the historical simulations (1850–2005), with the same variables in the instrumental (1950–2010) records (Supplementary Fig. 10). In addition, comparison of east Indonesian rainfall with both NINO3.4 SSTs and the SOI in model preindustrial control runs (500-year-long) and the LM+hist (850–2005 CE) simulations reveals statistically significant r values (Supplementary Table 3), which again demonstrates the strength of the model in simulating the dominant climate mode in the western Pacific. Details of the model characteristics (that is, forcings, atmospheric levels, atmospheric resolution) for the LM and historical simulations, and preindustrial control runs, can be found in ref. 58.

Data availability

Data from this paper are available at the NOAA World Data Center for Paleoclimatology (www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo).

Additional information

How to cite this article: Griffiths, M. L. et al. Western Pacific hydroclimate linked to global climate variability over the past two millennia. Nat. Commun. 7:11719 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11719 (2016).

References

Denton, G. H. et al. The last glacial termination. Science 328, 1652–1656 (2010).

England, M. H. et al. Recent intensification of wind-driven circulation in the Pacific and the ongoing warming hiatus. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 222–227 (2014).

Kosaka, Y. & Xie, S.-P. Recent global-warming hiatus tied to equatorial Pacific surface cooling. Nature 501, 403–407 (2013).

Meehl, G. A., Hu, A. & Santer, B. D. The mid-1970s climate shift in the Pacific and the relative roles of forced versus inherent decadal variability. J. Clim 22, 780–792 (2009).

Oppo, D. W., Rosenthal, Y. & Linsley, B. K. 2,000-year-long temperature and hydrology reconstructions from the Indo-Pacific warm pool. Nature 460, 1113–1116 (2009).

Tierney, J. E., Oppo, D. W., Rosenthal, Y., Russell, J. M. & Linsley, B. K. Coordinated hydrological regimes in the Indo-Pacific region during the past two millennia. Paleocean 25, (2010).

Zhang, P. Z. et al. A Test of climate, sun, and culture relationships from an 1810-year Chinese cave record. Science 322, 940–942 (2008).

Sachs, J. P. et al. Southward movement of the Pacific intertropical convergence zone AD 1400–1850. Nat. Geosci 2, 519–525 (2009).

Yan, H. et al. South China Sea hydrological changes and Pacific Walker Circulation variations over the last millennium. Nat. Commun 2, 293 (2011).

Conroy, J. L., Overpeck, J. T., Cole, J. E., Shanahan, T. M. & Steinitz-Kannan, M. Holocene changes in eastern tropical Pacific climate inferred from a Galapagos lake sediment record. Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 1166–1180 (2008).

Griffiths, M. L. et al. Increasing Australian-Indonesian monsoon rainfall linked to early Holocene sea-level rise. Nat. Geosci 2, 636–639 (2009).

Drysdale, R. N., Zanchetta, G., Hellstrom, J. C., Fallick, A. E. & Zhao, J.-X. Stalagmite evidence for the onset of the Last Interglacial in southern Europe at 129±1 ka. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L24708 (2005).

Fohlmeister, J. A statistical approach to construct composite climate records of dated archives. Quat. Geochron 14, 48–56 (2012).

Griffiths, M. L. et al. Evidence for Holocene changes in Australian-Indonesian monsoon rainfall from stalagmite trace element and stable isotope ratios. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 292, 27–38 (2010).

Hendy, C. H. The isotopic geochemistry of speleothems: The calculations of the effects of different modes of Formation on the isotopic composition of speleothems and their applicability as palaeclimate indicators. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 35, 801–824 (1971).

Vuille, M., Werner, M., Bradley, R. S., Chan, R. Y. & Keimig, F. Stable isotopes in east African precipitation record Indian ocean zonal mode. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L21705 (2005).

Yoshimura, K., Kanamitsu, M., Noone, D. & Oki, T. Historical isotope simulation using reanalysis atmospheric data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos 113, D19108 (2008).

Lewis, S. C., LeGrande, A. N., Kelley, M. & Schmidt, G. A. Water vapour source impacts on oxygen isotope variability in tropical precipitation during Heinrich events. Clim. Past 6, 325–343 (2010).

Lewis, S. C., LeGrande, A. N., Schmidt, G. A. & Kelley, M. Comparison of forced ENSO‐like hydrological expressions in simulations of the preindustrial and mid‐Holocene. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos 119, 7064–7082 (2014).

Konecky, B., Russell, J., Vuille, M. & Rehfeld, K. The Indian Ocean zonal mode over the past millennium in observed and modeled precipitation isotopes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 103, 1–18 (2014).

Fairchild, I. J. & Baker, A. Speleoethem Science John Wiley & Sons (2012).

Griffiths, M. L. et al. Hydrological control of the dead-carbon fraction in a Holocene tropical speleothem. Quat. Geochron 14, 81–93 (2012).

Fairchild, I. J. et al. Controls on trace element (Sr-Mg) compositions of carbonate cave waters: implications for speleothem climatic records. Chem. Geol. 166, 255–269 (2000).

Dulinski, M. & Rozanski, R. Formation of 13C/12C isotope ratios in speleothems: a semi-dynamic model. Radiocarbon 32, 7–16 (1990).

Drysdale, R. et al. Late Holocene drought responsible for the collapse of Old World civilizations is recorded in an Italian cave flowstone. Geology 34, 101–104 (2006).

Johnson, K. R., Hu, C., Belshaw, N. S. & Henderson, G. M. Seasonal trace-element and stable-isotope variations in a Chinese speleothem: The potential for high-resolution paleomonsoon reconstruction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 244, 394–407 (2006).

Genty, D. et al. Precise dating of Dansgaard–Oeschger climate oscillations in western Europe from stalagmite data. Nature 421, 833–837 (2003).

Fairchild, I. J. & Treble, P. C. Trace elements in speleothems as recorders of environmental change. Quat. Sci. Rev. 28, 449–468 (2009).

Cruz, F. W. et al. Evidence of rainfall variations in Southern Brazil from trace element ratios (Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca) in a Late Pleistocene stalagmite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 2250–2263 (2007).

Griffiths, M. L. et al. Abrupt increase in east Indonesian rainfall from flooding of the Sunda Shelf ∼9500 years ago. Quat. Sci. Rev. 74, 273–279 (2013).

Lachniet, M. S. Climatic and environmental controls on speleothem oxygen-isotope values. Quat. Sci. Rev. 28, 412–432 (2009).

Konecky, B., Russell, J. & Bijaksana, S. Glacial aridity in central Indonesia coeval with intensified monsoon circulation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 437, 15–24 (2016).

Hellstrom, J. C. & McCulloch, M. T. Multi-proxy constraints on the climatic significance of trace element records from a New Zealand speleothem. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 179, 287–297 (2000).

Mann, M. E. et al. Global signatures and dynamical origins of the Little Ice Age and Medieval Climate Anomaly. Science 326, 1256–1260 (2009).

Bond, G. et al. Persistent solar influence on north Atlantic climate during the Holocene. Science 294, 2130–2136 (2001).

Broccoli, A. J., Dahl, K. A. & Stouffer, R. J. Response of the ITCZ to Northern Hemisphere cooling. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L01702 (2006).

Wang, Y. J. et al. A high-resolution absolute-dated Late Pleistocene monsoon record from Hulu Cave, China. Science 294, 2345–2348 (2001).

Ayliffe, L. K. et al. Rapid interhemispheric climate links via the Australasian monsoon during the last deglaciation. Nat. Commun 4, 2908 (2013).

Tokinaga, H., Xie, S.-P., Deser, C., Kosaka, Y. & Okumura, Y. M. Slowdown of the Walker circulation driven by tropical Indo-Pacific warming. Nature 491, 439–443 (2012).

Emile-Geay, J., Cobb, K. M., Mann, M. E. & Wittenberg, A. T. Estimating central equatorial Pacific SST variability over the past millennium. Part 2: Reconstructions and implications. J. Clim 26, 2329–2352 (2012).

Yan, H. et al. Dynamics of the intertropical convergence zone over the western Pacific during the Little Ice Age. Nat. Geosci 8, 315–320 (2015).

Denniston, R. F. et al. Extreme rainfall activity in the Australian tropics reflects changes in the El Niño/Southern Oscillation over the last two millennia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 4576–4581 (2015).

Bard, E., Raisbeck, G., Yiou, F. & Jouzel, J. Solar irradiance during the last 1200 years based on cosmogenic nuclides. Tellus B 52, 985–992 (2000).

Bird, B. W. et al. A 2,300-year-long annually resolved record of the South American summer monsoon from the Peruvian Andes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 8583–8588 (2011).

Thompson, L. et al. Annually resolved ice core records of tropical climate variability over the past ∼1800 years. Science 340, 945–950 (2013).

Reuter, J. et al. A new perspective on the hydroclimate variability in northern South America during the Little Ice Age. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L21706 (2009).

Moy, C. M., Seltzer, G. O., Rodbell, D. T. & Anderson, D. M. Variability of El Niño/Southern Oscillation activity at millennial timescales during the Holocene epoch. Nature 420, 162–165 (2002).

Lachniet, M. S. et al. A 1500‐year El Niño/Southern Oscillation and rainfall history for the isthmus of Panama from speleothem calcite. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos 109, D20117 (2004).

Li, J. B. et al. Interdecadal modulation of El Niño amplitude during the past millennium. Nat. Clim. Change 1, 114–118 (2011).

Yan, H. et al. A record of the Southern Oscillation Index for the past 2000 years from precipitation proxies. Nat. Geosci 4, 611–614 (2011).

Newton, A., Thunell, R. & Stott, L. Climate and hydrographic variability in the Indo-Pacific Warm Pool during the last millennium. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, (2006).

Cobb, K. M., Charles, C. D., Cheng, H. & Edwards, R. L. El Niño/Southern Oscillation and tropical Pacific climate during the last millennium. Nature 424, 271–276 (2003).

Conroy, J. L., Overpeck, J. & Cole, J. El Niño/Southern Oscillation and changes in the zonal gradient of tropical Pacific sea surface temperature over the last 1.2 ka. PAGES News 18, 32–34 (2010).

Rustic, G. T., Koutavas, A., Marchitto, T. M. & Linsley, B. K. Dynamical excitation of the tropical Pacific Ocean and ENSO variabilty by Little Ice Age cooling. Science 350, 1537–1541 (2015).

Vecchi, G. A. et al. Weakening of tropical Pacific atmospheric circulation due to anthropogenic forcing. Nature 441, 73–76 (2006).

Held, I. M. & Soden, B. J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J. Clim 19, 5686–5699 (2006).

Clement, A. C., Seager, R., Cane, M. A. & Zebiak, S. E. An ocean dynamical thermostat. J. Clim 9, 2190–2196 (1996).

Landrum, L. et al. Last millennium climate and its variability in CCSM4. J. Clim 26, 1085–1111 (2011).

Ahmed, M. et al. Continental-scale temperature variability during the past two millennia. Nat. Geosci 6, 339–346 (2013).

Neukom, R. et al. Inter-hemispheric temperature variability over the past millennium. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 362–367 (2014).

Timmermann, A., An, S.-I., Krebs, U. & Goosse, H. ENSO suppression due to weakening of the North Atlantic thermohaline circulation. J. Clim 18, 3122–3139 (2005).

Ault, T., Deser, C., Newman, M. & Emile‐Geay, J. Characterizing decadal to centennial variability in the equatorial Pacific during the last millennium. Geophys. Res. Lett. 6, 3450–3456 (2013).

Laepple, T. & Huybers, P. Ocean surface temperature variability: large model–data differences at decadal and longer periods. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 16682–16687 (2014).

Yu, K. F. et al. U-series dating of dead Porites corals in the South China Sea: Evidence for episodic coral mortality over the past two centuries. Quat. Geochron 1, 129–141 (2006).

Hellstrom, J. C. U–Th dating of speleothems with high initial 230Th using stratigraphical constraint. Quat. Geochron 1, 289–295 (2006).

Zhou, H. Y., Zhao, J. X., Qing, W., Feng, Y. X. & Tang, J. Speleothem-derived Asian summer monsoon variations in central China, 54–46 ka. J. Quat. Sci 26, 781–790 (2011).

Cheng, H. et al. Improvements in 230Th dating, 230Th and 234U half-life values, and U–Th isotopic measurements by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 371, 82–91 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) for operational support and are particularly grateful to Neil Anderson, Garry Smith, Bambang Suwargadi and Linda Ayliffe, who provided expertise in cave conservation and technical assistance. Heather Scott-Gagan provided technical assistance at ANU. The work in Indonesia was carried out under LIPI research permit number 04057/SU/KS/2006. Financial support for the research was provided by Australian Research Council Discovery grants DP0663274 and DP1095673 to M.K.G., R.N.D., J.-X.Z., J.C.H. and W.S.H. This research was also supported by a 2010–2012 NOAA/UCAR Climate and Global Change Postdoctoral Fellowship to M.L.G. and an internal summer 2013 research grant through William Paterson University. Support for A.K.K. was provided by a 2007–2010 Lewis and Clark College Mellon Research Initiative Fellowship and support for J.E.C. was provided by the US NSF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K.G., R.N.D. and W.S.H collected the samples from Liang Luar cave in August 2006. M.L.G. sampled stalagmite LR06-B1, carried out the data analysis and interpreted the results. A.K.K. and J.E.C. undertook the sample preparation and isotope analyses for LR06-B3. K.R.J. carried out the isotope measurements on LR06-B1. J.C.H. and J.-X. Z. performed the 230Th/234U dating and age-modelling. B.I.C. carried out the model analysis and interpretation. M.L.G., M.K.G, A.K.K., R.N.D. and J.E.C. wrote the manuscript with contributions from the other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-10, Supplementary Tables 1-3 and Supplementary References (PDF 3500 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Griffiths, M., Kimbrough, A., Gagan, M. et al. Western Pacific hydroclimate linked to global climate variability over the past two millennia. Nat Commun 7, 11719 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11719

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11719

This article is cited by

-

Mid-to-late Holocene climate variability in coastal East Asia and its impact on ancient Korean societies

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Abrupt change in tropical Pacific climate mean state during the Little Ice Age

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)

-

Multi-proxy validation of glacial-interglacial rainfall variations in southwest Sulawesi

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)

-

Iberian hydroclimate variability and the Azores High during the last 1200 years: evidence from proxy records and climate model simulations

Climate Dynamics (2023)

-

Ice-volume and insolation influences on hydroclimate changes in central eastern China during the antepenultimate glacial period

Science China Earth Sciences (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.