Abstract

The field of systems biology is often held back by difficulties in obtaining comprehensive, high-quality, quantitative data sets. In this paper, we undertook an interlaboratory effort to generate such a data set for a very large number of cellular components in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a widely used model organism that is also used in the production of fuels, chemicals, food ingredients and pharmaceuticals. With the current focus on biofuels and sustainability, there is much interest in harnessing this species as a general cell factory. In this study, we characterized two yeast strains, under two standard growth conditions. We ensured the high quality of the experimental data by evaluating a wide range of sampling and analytical techniques. Here we show significant differences in the maximum specific growth rate and biomass yield between the two strains. On the basis of the integrated analysis of the high-throughput data, we hypothesize that differences in phenotype are due to differences in protein metabolism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are many definitions and interpretations of systems biology, but most involve mathematical modelling, high-throughput (or omics) analysis, mapping of interactions between cellular components and quantification of dynamic responses in living cells1,2,3,4,5. In most cases, the objective of systems biology is to obtain a quantitative description of the biological system under study, and this quantitative description is ideally in the form of a mathematical model that can be used to simulate the operations of the biological system. Even though some mathematical modelling concepts rely only on limited data sets (for example, flux balance analysis), most systems biology efforts will require large sets of high-quality experimental data that enable, for example, to discriminate between different model structures. Generation of such data is therefore the core of many studies that use the systems biology approach. However, the infrastructure and expertise needed to generate the large number of different data required for advanced systems biology studies (for example, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) is normally beyond the capabilities of a single laboratory. Therefore, there is a trend towards multilaboratory collaboration projects and the establishment of curated databases that contain high-quality data sets6. To ensure proper documentation of experiments, some effort has also been directed at establishing protocol formats, such as MIAME (Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment) for DNA array experiments7, MIAPE (Minimum Information About a Proteomics Experiment) and PRIDE (PRoteomics IDEntification) for proteome analysis8,9, protocols for microbial metabolome analysis10, and even protocols for documentation of mathematical models such as MIRIAM11 (Minimum Information Requested In the Annotation of biochemical Models). Even though these protocol formats aim to ensure proper documentation of the actual experiments, there is still a need for consolidation of applied experimental conditions and procedures, in order to allow the generation of increasingly large, coherent data sets for the same organism or strain that will eventually represent a rich resource for advanced mathematical modelling and contribute to our understanding of the living cell.

In this study, The Yeast Systems Biology Network (YSBN) undertook a major effort to consolidate and compare experimental conditions, procedures and protocols applied for the experimental part of yeast systems biology in 10 different European laboratories, and at the same time performed a comparative analysis of different quantitative analytical methods. This has resulted in the establishment of a well-documented experimental 'systems biology pipeline' that is illustrated in Figure 1. The 'pipeline' allows for the comparison of different yeast strains or the comparison of a single yeast strain grown under different conditions. In this study, we evaluated the 'pipeline' by comparing two different yeast strains grown under two different conditions in biorectors, namely, a traditional batch culture (nutrient excess) and a glucose-limited chemostat culture (specific growth rate controlled by the rate of supply of the limiting nutrient, glucose).

Two yeast strains were compared: YSBN2, a newly constructed prototrophic strain closely related to the originally sequenced S288c strain, and CEN.PK113-7D, a widely used reference strain for physiological studies and industrial applications. Each strain was grown in well-controlled bioreactors under both substrate excess (batch) and substrate-limited growth conditions (chemostat), each in triplicate, at a single location. A fast sampling sequence and parallel processing allowed the reliable and reproducible generation of the necessary material for multiplexed omics analyses. Samples were shipped to the different laboratories involved in this project for analysis of the transcriptome, the metabolome and the activity key enzymes, each using multiple platforms/techniques. The data obtained were collected and integrated, resulting in a very thorough phenotypic characterization of the two strains. qPCR: quantitative-PCR; TRAC: TRanscript analysis with Affinity Capture; HPLC: high-performance liquid chromatography; MS: mass spectrometry; LC: liquid chromatography; GC: gas chromatography; TOF: time-of-flight mass spectrometry; DAD: diode array detection.

The resulting data set will constitute a valuable reference for further studies using these two strains and hence advance the field of yeast systems biology. Furthermore, we were able to illustrate how comprehensive information on multiple omics levels (for example, fluxes, transcripts and metabolites) can be used collectively to generate hypotheses that would not arise from their individual analysis. Specifically, the integrated analysis of our data set pointed to differences in the regulation of protein metabolism as the source of the pronounced physiological differences observed (maximum specific growth rate and biomass yield on substrate) between the two strains investigated.

Results

Construction of a new set of reference S. cerevisiae strains

The first step in the establishment of our experimental systems biology pipeline was to find appropriate yeast strains that would be of interest. In the yeast community, a range of different yeast strains are being used, with the strain series BY, W303 and CEN.PK being the most frequently used12. The BY strain series is a derivative of the originally sequenced strain S288c, for which there is a complete gene knockout collection. The CEN.PK strain series is used widely in physiological studies and, because of its rapid growth, is also often used for metabolic engineering studies12. Physiological studies are generally best performed with prototrophic strains, whereas the BY series strains carry a number of auxotrophies that may cause problems for quantitative studies of cellular physiology. Hence, there was a need to generate prototrophic strains in the S288c background that nonetheless carried some genetic markers that would permit checks against contamination, in large-scale or long-term cultures, and facilitate subsequent genetic crosses (for instance, of evolved derivatives). For this reason, two diploid strains, YSBN1 and YSBN2, were generated from FY1 and FY2, two uracil auxotrophic strains that are direct derivatives of S288c (ref. 13). FY2 is the strain from which the BY strain series14, and hence the strain from which the complete knockout collection15, was derived. YSBN1 and YSBN2 are prototrophic strains that carry drug resistance markers inserted into their genomes at a phenotypically neutral site16,17. Besides the two diploid strains, a set of haploid strains with the two different mating types was also constructed (Supplementary Table S1). All the strains are available from EUROSCARF (http://web.uni-frankfurt.de/fb15/mikro/euroscarf/yeast.html).

Comparison of the two strains under two growth conditions

To evaluate the newly constructed strain, we performed a detailed comparative analysis of the YSBN2 strain with the widely used strain CEN.PK113-7D. Each strain was grown in batch cultures, which were sampled in the mid-exponential growth phase (on glucose) (Supplementary Fig. S1). After the diauxic shift and the ethanol growth phase, the cultures were used to initiate chemostat cultivations, which were sampled after steady-state conditions were achieved (Supplementary Fig. S2). Fermentations were carried out in triplicate with each strain and each condition, resulting in a total of 12 samples. The detailed cultivation protocols are given as Supplementary Methods. The experiments were conducted in well-controlled bioreactors in a single laboratory, which ensured a very high degree of reproducibility (Table 1), and samples were then shipped to different laboratories for analysis. The key physiological parameters of each strain under both conditions are summarized in Table 1. From the initial analysis it is interesting to observe that the maximum specific growth rate of the CEN.PK strain is significantly higher than that of the YSBN strain, by approximately 25%, whereas its biomass yield under carbon-limited conditions (chemostat) is significantly lower, by approximately 10%. The differences in biomass yield cannot be explained by major differences in the contents of total protein or carbohydrate (Supplymentary Note 1). Thus, one could speculate whether the ability of CEN.PK to grow faster when resources are abundant has come at the expense of efficiency in carbon and energy utilization under nutrient limitation.

Our analysis involved sampling for determination of mRNA levels, using DNA arrays (Affymetrix and Agilent), quantitative PCR (qPCR) and TRAC (TRanscript analysis with Affinity Capture)18; enzyme activities, using optimized and in vivo-like assays; and endometabolome, using several analytical platforms including liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), gas chromatography time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC-TOF), two dimensional gas chromatography coupled to time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GCxGC-TOF), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), high-performance liquid chromatography-diode array detection (HPLC-DAD) and enzymatic analysis. Table 2 gives an overview of the sampling procedure, which was designed taking into account the large number of samples needed and the fast turnover of some molecules to be analysed (for example, intracellular metabolites). Fast sampling and parallel sample processing required a team of five people, of whom three carried out the same key steps in all 12 sampling procedures. Detailed protocols of all sampling and processing techniques are given in Supplementary Methods.

Combination of omics platforms

Transcripts were measured using a range of different methods. Genome-wide analysis was performed using both the Affymetrix and Agilent platforms. qPCR was performed in two different laboratories and used to quantify the expression of a number of selected genes (Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Fig. S3). TRAC analysis was also performed, as it allows for multiplex detection of mRNA targets simultaneously from a large number of samples (Supplementary Fig. S4). Comparison of mRNA levels determined in four different laboratories using the four different analytical methods shows a good overall consistency (Fig. 2). qPCR analysis performed in one of the laboratories was used to check the consistency of 33 genes that were found to have significantly changed expression on the basis of an analysis of variance of the Affymetrix data. This analysis shows very clearly that, when high-quality platforms for genome-wide transcription analysis are used, one obtains equally quantitative information as by qPCR (Supplementary Table S3), both in terms of significance and changes in expression levels (Fig. 2). The TRAC analysis also showed a fairly good consistency with DNA array data, but about 15% of the analysed transcripts had a very poor correlation, on the basis of analysis of the four different samples (2 strains × 2 conditions), and another 15% had a Pearson's correlation coefficient <0.85 (Supplementary Table S4). We did not find a linear correlation between the Affymetrix and Agilent data (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs S5 and S6), but this can be explained by the use of a different dynamic scanning range by the Agilent scanner. However, the significant genes identified by analysis of variance using the two platforms were fairly consistent; that is, out of a total of 410 transcripts found to be significantly changed in response to growth conditions (including both strains and both array platforms), 241 transcripts were found consistently by both platforms (Supplementary Figs S5, S7 and S8). Thus, we conclude that both platforms are equally strong; however, in light of the large data sets that are already available with the Affymetrix, we recommend the use of this platform, as this will allow for further expansion of the already large database of Affymetrix-based transcriptome data.

The correlation matrix shows how the different analytical platforms correlate with respect to measurement of mRNA. The correlation between each pair of platforms is shown both as data in a black box (the upper right corner) and the Pearson's correlation coefficient in a red box (the lower left corner), which are in the corresponding row and column as the pair of platforms compared (the diagonal of the matrix).

We also measured the activity levels of key glycolytic enzymes in cell extracts. Measurements taken in two different laboratories yield a good overall consistency in the data (Supplementary Fig. S9, Supplementary Data 1). In connection with the experiment, we also evaluated a new approach to quantify enzyme activities using assay conditions designed to better represent in vivo-like conditions (where the assay medium is designed to mimic the actual intracellular environment, see Methods and Supplementary Methods), as opposed to the typical approach of using optimal conditions for each enzyme (Fig. 3)19. We found that with the in vivo-like assays the range of enzyme activities was in the same order of magnitude as the glycolytic flux, which was not observed using traditional analysis of glycolytic enzyme activities.

Bars show enzyme activities for the different enzymes in the glycolysis. Error bars show SEM based on three biological replicates. Dark blue: YSBN strain in batch; dark red: CEN.PK strain in batch; light blue: YSBN strain in chemostat; light red: CEN.PK strain in chemostat. HXK: hexokinase; PGI: phosphoglucose isomerase; PFK: phosphofructokinase; ALD: alanine dehydrogenase; TPI: triosephosphate isomerase; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PGK: Phosphoglycerate kinase; GPM: 3-phosphoglycerate mutase; ENO: enolase; PYK: pyruvate kinase; PDG: pyruvate decarboxylase; ADH: alcohol dehydrogenase.

Metabolome samples were analysed independently by seven participating laboratories according to their own standard operating procedures (see Supplementary Methods for detailed description). Four variations in extraction protocol, five analytical platforms (LC-MS, GC-TOF, GCxGC-TOF, enzymatic, HPLC-DAD) and three internal standard strategies were used in different combinations. The interlaboratory comparison shows that absolute concentration estimates from different laboratories can vary by up to threefold, even for identical sample processing (see Supplementary Note 2, Supplementary Data 2). However, when comparing only the relative concentration differences between growth conditions or strains, all laboratories deliver a surprisingly consistent picture. Furthermore, relevant metabolite ratios (for example, mass-action ratios) based on measurements from different laboratories were comparable. As redundancy was obtained with heterogeneous preparation protocols and orthogonal analytical methods, we conclude that, even with the current state-of-the-art metabolomics, ratiometric measurements still have much higher reliability than do absolute estimates.

Integrated analysis

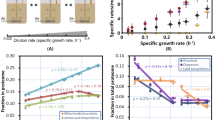

Integrated data analysis started by considering the exo-metabolome data, which provided information about the 'gross phenotype'. Through measurements of all key nutrients and metabolites being secreted or released into the medium (including analysis of the gas phase), it was possible to obtain very precise measurements of the overall metabolic fluxes, and these are summarized in Figure 4. Under substrate-excess growth conditions (batch cultivation), it was observed that the CEN.PK113-7D strain exhibited a >20% higher glucose uptake rate, which was accompanied by a higher flux towards ethanol. The specific carbon dioxide production not associated with ethanol production was the same in the two strains, despite the fact that the specific oxygen uptake rate was more than twofold higher in the CEN.PK113-7D strain compared with the YSBN2 strain. This suggests that the higher oxygen uptake rate allowed for a reduced glycerol production by the CEN.PK113-7D strain, as overflow towards glycerol production under fermentative growth conditions serves as an alternative NADH sink. The higher glycolytic flux in the CEN.PK113-7D strain at substrate excess growth conditions (batch) is not associated with increased activities of glycolytic enzymes (see Fig. 3) or large differences in the levels of glycolytic intermediates (Fig. 4b). For practically all of the glycolytic enzymes, there was a higher activity in the YSBN2 strain compared with the CEN.PK113-7D strain (results were confirmed by measurements in two independent laboratories, see Supplementary Fig. S9). In the comparison between growth conditions, the higher glycolytic flux in batch culture compared with that in the chemostat is associated with higher enzyme activities for practically all glycolytic enzymes in both strains. However, as the enzyme activity level was only about 50% lower in the chemostat compared with the batch cultures, it is clear that enzyme activities cannot alone describe the almost 10-fold lower glycolytic flux in the chemostat. This indicates that the adjustment of the glycolytic flux to fermentative conditions is to a large extent determined by changes in the levels of metabolic intermediates and effectors; that is, flux control is primarily at the metabolic level. This finding is consistent with earlier more detailed studies on glycolysis18,19,20,21,22. The metabolome data, however, do not provide any insight into the differences in fluxes between the two strains, as there are very small differences in metabolite levels between the different strains, and most differences indicate slightly higher metabolite concentrations in the YSBN2 strain, which has lower fluxes. Finally, the higher activity of glycolytic enzymes in the batch cultures is associated with increased expression of several glycolytic genes (PFK1, TPI1, ENO2, TDH2, TDH3, PYK1, PDC1, ADH1; Supplementary Fig. S3). However, the slightly higher enzyme activities found in the YSBN2 strain (compared with CEN.PK113-7D) are not associated with higher expression of the respective genes.

(a) From measurements of the concentrations of biomass, glucose, ethanol and glycerol in the medium and of carbon dioxide and oxygen in the exhaust gas, the overall exchange rates can be calculated. The CEN.PK113-7D strain (blue data) has a higher glucose uptake rate, a higher flux towards ethanol and a higher oxygen uptake rate, whereas the carbon dioxide production rate is about the same for the two strains (the flux towards CO2 is corrected for the amount of CO2 formed in relation to ethanol production). The YSBN2 strain (red data) has a higher glycerol production rate in the batch fermentation. In the chemostat culture, the biomass yield is higher for the YSBN2 strain (red data) and this is accompanied by higher specific fluxes in the CEN.PK113-7D strain. (b) Measurement of glycolytic metabolites, in which it is found that for both strains there is an increase in most of the glycolytic metabolites in the batch culture compared with the chemostat (red bars indicate increased metabolite levels). Numbers are log2 values of the ratio between batch and chemostat levels.

Although there is no direct correlation between fluxes, enzyme activities and intracellular metabolite levels, it is striking that under batch conditions the levels of practically all amino acids were noticeably higher in CEN.PK113-7D than in the YSBN2 strain. This led us to perform a more detailed analysis of the gene expression data. Using methods for integrative analysis23,24, we calculated enriched gene ontology (GO) terms for transcripts differing significantly between the two strains at both growth conditions, as well as for reporter metabolites24 and reporter transcription factors25. These methods allow for identification of transcriptional hotspots in metabolic networks, that is, metabolites around which there are large transcriptional changes, and transcription factors (TFs) that drive key transcriptional responses. The results of this analysis are shown in Table 3 and Supplementary Tables S5–S10. In Table 3, representative GO terms indicate sets of genes that had significant differences in expression between the two strains. Reporter metabolites indicate locations in metabolism around which there are large transcriptional differences, and reporter TFs indicate TFs for which there are significant changes in expression of associated genes. For batch cultures, the analysis points to a clear effect on amino-acid transport, with several amino-acid transporter genes being differentially expressed between the two strains (most transporters being expressed at a higher level in YSBN2). Further, there is a distinct nitrogen catabolite repression response in the YSBN2 strain in the batch culture, with Gln3p and Gat1p being identified as reporter TFs, that is, TFs that control a set of genes that have significant transcriptional changes. Thus, there are clearly differences in how the two strains control amino-acid biosynthesis. YSBN2 expresses many amino-acid transporters even when growing on minimal medium (without amino-acid supplementation) and CEN.PK113-7D is able to maintain higher intracellular amino-acid pools. The latter may be important for ensuring efficient loading of the tRNAs needed for protein biosynthesis, which in turn could be the basic explanation for the higher specific growth rate of CEN.PK113-7D.

Discussion

The molecular explanation for the higher glucose uptake of CEN.PK113-7D and the differences in overall fluxes through the central carbon metabolism between the two strains has not been identified yet. As mentioned previously, several studies have shown that there is complex regulation of the glycolytic flux, and that overexpression of glycolytic genes in yeast does not result in an increased flux through this pathway26,27. We hypothesize that the higher glucose uptake of CEN.PK113-7D could arise from the differences in protein biosynthesis in the two strains. Protein synthesis is costly in terms of Gibbs-free energy provided in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and the increased glycolytic flux in the CEN.PK113-7D strain could arise from a pull of ATP and other cofactors needed for biomass production. Changes in protein biosynthesis, protein catabolism and proteolysis in the two strains could also explain the lower biomass yield of CEN.PK113-7D in chemostat culture compared with the YSBN2 strain. We find GO terms on protein catabolism and proteolysis and a large number of genes associated with these terms were significantly more highly expressed in the CEN.PK113-7D strain compared with the YSBN2 strain. This is clearly linked to the TF Rpn4, which regulates the 26S proteosome. This indication of increased protein turnover in CEN.PK113-7D is also consistent with our finding of a Gcn4 response in that strain. Gcn4 is a TF that positively regulates the transcription of a large number of genes that encode for amino-acid biosynthetic enzymes. In fact, a large number of these genes are also identified as being significantly more highly expressed in CEN.PK113-7D compared with YSBN2. Taken together, these observations strongly point to higher amino-acid and protein biosynthesis, as well as to increased protein degradation in CEN.PK113-7D (Fig. 5). As amino-acid synthesis and polymerization represent the most energetically costly process in biomass formation, a higher rate of protein turnover in the CEN.PK113-7D strain could certainly explain the lower biomass yield. This provides a molecular hypothesis for the general statement made above; the CEN.PK113-7D strain has a more effective machinery for rapid protein biosynthesis and it can thereby grow faster, but the effect of this is a less-efficient utilization of the carbon and energy source under growth-limiting conditions. This is consistent with a thermodynamic analysis of microbial growth, where it is found that there is a trade-off between the Gibbs-free energy dissipation as a driving force for growth and biomass yield28. The changes oberved in the CEN.PK113-7D strain are summarized in Figure 5, in which it is illustrated that increased activity of protein catabolism and proteolysis results in the formation of a futile cycle in which there is a net consumption of ATP, and this imposes a requirement for increased catabolism and respiration that ensures the supply of ATP.

Differences were observed in the regulation of metabolism between the two strains in chemostat culture. Downregulation of amino-acid biosynthesis, protein catabolism and proteolysis in the YSBN2 strain via GCN4 and RPN4 is indicated in bold blue lines. A lower requirement of ATP for biomass formation is associated with lower specific rates of catabolism and respiration, indicated in thin blue lines. This results in a higher yield of biomass on substrate for the YSBN2 strain.

Finally, it can be mentioned that we observed, under both growth conditions, higher expression levels of genes involved in sterol biosynthesis in CEN.PK113-7D than in YSBN2. This is consistent with findings that the level of ergosterol is significantly higher in CEN.PK113-7D than in the S288c strain, to which the YSBN2 strain is closely related29.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that through integrative analysis of comprehensive data sets it is possible to suggest molecular explanations for observed phenotypes, which would not be possible from a single omics data set. Thus, systems biology analysis can be used to provide a hypothesis for differences in gross phenotypes such as growth rate and biomass yield on glucose, and through follow-up studies in which specific molecular processes are analysed, the provided hypothesis can be evaluated, resulting in novel biological insight. Furthermore, our interlaboratory comparison of different methods and the detailed protocols provided allows to implement the appropriate analytical platform in connection with systems biological studies of yeast in different laboratories. Finally, we are confident that our interlaboratory comparison of different experimental methods for omics analysis provides very useful reference data sets for two yeast strains, and these reference data sets will allow further advancement of yeast systems biology. This holds particularly in connection with further use of the newly constructed YSBN strains that represent a valuable resource for the yeast systems biology community as they are prototrophic (thus suitable for physiological studies) and yet closely related to the widely used BY-strain series.

Methods

Strains

A set of new reference strains was constructed, on the basis of an S288c background, which are prototrophic and carry drug resistance markers. Haploid strains were derived from FY2 (MAT α ura3-52) and FY3 (MAT a ura3-52) (ref. 13) by insertion of antibiotic resistance cassettes and a functional URA3 gene. Diploid strains were obtained by crossing of the haploids. Details on strain construction are provided in Supplementary Methods. For the fermentation experiments we used the diploid YSBN2 (ho∷Ble/ho∷HphMX4) and the commonly used reference strain CEN.PK113-7D (ref. 12).

Medium and cultivation conditions

Each strain was grown in triplicate. The six fermentations were carried out at Delft University of Technology (TUD) from a single batch of defined minimal medium, with 7.5 g l−1 glucose and 0.3 g l−1 ethanol as carbon sources (the latter to prevent oscillations in the chemostat phase). Before inoculation of fermentors, the medium was supplemented with glucose for an initial concentration of 30 g l−1. Cultivations were carried out under aerobic conditions, in bioreactors equipped with continuous data acquisition (Applikon; B. Braun Biotech), at 30 °C, pH 5.0, with a working volume of 4 l, 0.3 bar overpressure, an aeration rate of 0.5 v.v.m. (120 l h−1) and a stirrer speed of 500 r.p.m. The batch cultures were sampled in exponential glucose-consumption phase. Glucose-limited chemostat cultures were initiated at the end of the batch phase, carried out at a dilution rate of 0.1 h−1 and sampled after at least five residence times of constant dissolved oxygen and off-gas readings. Further details on medium preparation and the fermentation protocol are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Sampling sequence and processing

In total, 12 'omics' sampling procedures were performed, each resulting in over 40 samples. Each type of sample was obtained according to a rapid and well-defined sequence lasting <4 min. This provided material for all analyses while preventing unwanted changes induced by perturbation of the cultivation (see Supplementary Methods). Samples for metabolomics were withdrawn using a custom-made low dead-volume rapid sampling setup30. Replicate samples were processed according to the standard procedures in use at each laboratory, resulting in seven protocol variations, although all involved cold methanol quenching31 and boiling ethanol extraction32 as the key steps, followed by evaporation to dryness before distribution. Samples for transcriptomics were collected by overpressure and quenched in liquid nitrogen. After thawing and washing, the samples were extracted in acidic phenol/chloroform33 before distribution. Samples for enzyme activity assays were collected by overpressure, quenched on ice and washed in potassium buffer before freezing and distribution23. Detailed descriptions of all sample processing protocols are provided as Supplementary Methods. All samples were shipped to the other laboratories on dry ice by overnight courier.

Transcriptome analysis

Transcriptomics analyses were carried out at four laboratories using four different platforms. Gene expression analysis was performed using both Affymetrix (Yeast Genome 2.0) and Agilent (on Agilent 4×44 K) microarray technologies performed at Technical University of Denmark (DTU). The same 12 samples (two strains, two conditions in triplicate) were analysed by both methods. Data are available at Gene Expression Omnibus with accession number GSE24234. Data analysis for each platform was performed independently with the Bioconductor package (http://www.bioconductor.org) for the R programming environment (cran.r-project.org). A subset of about 40 genes (selected on the basis of results from microarray analysis) were measured using quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT–PCR) at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VUA) and Bogazici University (BU), as well as by TRanscript analysis with the aid of the Affinity Capture (TRAC) method18 at VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland (VTT). Five housekeeping genes (TOA2, IPP1, PDA1, PDI1 and SHE10) were carefully chosen and pooled as the reference in the qPCR analysis. All primers were designed, checked by in silico PCR, and PCR for product specificity and the annealing temperature was optimized for the pool of primers. The transciptome data from the two microarray platforms, together with transcript levels measured using qPCR and TRAC, were compared with each other, and Pearson's correlation coefficient was calculated between each pair of data sets to validate the results and evaluate the comparability of data generated in different laboratories using different techniques.

Enzyme activity analysis

Enzyme activities were determined at TUD and VUA. Furthermore, measurements at VUA were taken using two different protocols. Cell-free extracts were prepared from washed samples by bead-beating with acid-washed glass beads (425–600 microns, Sigma) in a Qbiogene a Qbiogene FastPrep (MP Biomedicals), followed by removal of debris by centrifugation (36,000 g, 4 °C, 20 min). Enzyme activities were determined spectrophotometrically in freshly prepared extracts by NAD(P)H-linked assays in either a Novostar, BMG Labtech (VUA), or a TECAN GENios Pro microtiterplate reader (TUD). Standard assays were performed according to Jansen et al.34 In addition, the VUA group also measured activities under a recently proposed in vivo-like assay medium designed to mimic the intracellular environment19. All results are presented in μmol min−1 mgprotein−1.

Metabolome analysis

Metabolite analyses were carried out at seven locations: Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH), DTU, TUD, VTT, VUA, University of Stuttgart (US) and University of Cambridge (UC). Different complementary analytical approaches were available at each laboratory, including several MS-based platforms (ETH, TUD, DTU, VTT and UC), as well as HPLC-DAD (US), nuclear magnetic resonance (UC) and enzymatic assays (VUA). Determinations were made on samples as shipped after resuspension and minimal conditioning, such as removal of debris by centrifugation or filtration, followed by any platform-specific sample preparation, such as derivatization. Quantification was based on analysis of pure standards by means of different internal standard compounds/strategies, including Cl-phenylalanine (DTU), norvaline (ETH), U-13C-labelled cell extract (TUD, ETH, VTT) and defined mixes of isotopically labelled compounds (VTT, UC). Each analytical method is described in detail in the Supplementary Methods. Intracellular metabolite levels are presented as μmol gDW−1.

Integrated data analysis

The representative GO terms were identified using hypergeometric tests on the genes that had significant differences in expression for the two strains. The reporter metabolites, calculated using the algorithm of Patil and Nielsen24, indicate locations in the metabolism around which there are large transcriptional differences between the two strains. The reporter TFs, calculated using the algorithm of Oliveira et al.25, indicate TFs for which there are significant changes in the expression of the genes they are controlling.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Canelas, A.B. et al. Integrated multilaboratory systems biology reveals differences in protein metabolism between two reference yeast strains. Nat. Commun. 1:145 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1150 (2010).

Accession codes

References

Ideker, T. et al. Integrated genomic and proteomic analyses of a systematically perturbed metabolic network. Science 292, 929–934 (2001).

Kitano, H. Systems biology: a brief overview. Science 295, 1662–1664 (2002).

Brent, R. A partnership between biology and engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 1211–1214 (2004).

Barrett, C. L., Kim, T. Y., Kim, H. U., Palsson, B. O. & Lee, S. Y. Systems biology as a foundation for genome-scale synthetic biology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 17, 488–492 (2006).

Bruggeman, F. J. & Westerhoff, H. V. The nature of systems biology. Trends Microbiol. 15, 45–50 (2007).

Reguly, T. et al. Comprehensive curation and analysis of global interaction networks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. 5, 11 (2006).

Brazma, A. et al. Minimum information about a microarray experiment (MIAME)-toward standards for microarray data. Nat. Genet. 29, 365–371 (2001).

Taylor, C. F. et al. The minimum information about a proteomics experiment (MIAPE). Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 887–893 (2007).

Martens, L. et al. PRIDE: the proteomics identifications database. Proteomics 5, 3537–3545 (2005).

van der Werf, M. J. et al. Standard reporting requirements for biological samples in metabolomics experiments: microbial and in vitro biology experiments. Metabolomics 3, 189–194 (2007).

Le Novere, N. et al. Minimum information requested in the annotation of biochemical models (MIRIAM). Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 1509–1515 (2005).

van Dijken, J. P. et al. An interlaboratory comparison of physiological and genetic properties of four Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 26, 706–714 (2000).

Winston, F., Dollard, C. & Ricupero-Hovasse, S. L. Construction of a set of convenient Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that are isogenic to S288C. Yeast 11, 53–55 (1995).

Brachmann, C. B. et al. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14, 115–132 (1998).

Giaever, G. et al. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 418, 387–391 (2002).

Baganz, F. et al. Quantitative analysis of yeast gene function using competition experiments in continuous culture. Yeast 14, 1417–1427 (1998).

Oliver, S. G., Winson, M. K., Kell, D. B. & Baganz, F. Systematic functional analysis of the yeast genome. Trends Biotechnol. 16, 373–378 (1998).

Rautio, J. J. et al. Rapid and multiplexed transcript analysis of microbial cultures using capillary electophoresis-detectable oligonucleotide probe pools. J. Microbiol. Methods 65, 404–416 (2006).

van Eunen, K. et al. Measuring enzyme activities under standardized in vivo-like conditions for systems biology. FEBS J. 277, 749–760 (2010).

van Hoek, P., van Dijken, J. P. & Pronk, J. T. Regulation of fermentative capacity and levels of glycolytic enzymes in chemostat cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 26, 724–736 (2000).

Daran-Lapujade, P. et al. The fluxes through glycolytic enzymes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are predominantly regulated at posttranscriptional levels. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 15753–15758 (2007).

Postmus, J. et al. Quantitative analysis of the high temperature-induced glycolytic flux increase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals dominant metabolic regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 23524–23532 (2008).

van den Brink, J. et al. Dynamics of glycolytic regulation during adaptation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to fermentative metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 5710–5723 (2008).

Patil, K. R. & Nielsen, J. Uncovering transcriptional regulation of metabolism by using metabolic network topology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 2685–2689 (2005).

Oliveira, A. P., Patil, K. R. & Nielsen, J. Architecture of transcriptional regulatory circuits is knitted over the topology of bio-molecular interaction networks. BMC Syst. Biol. 2, 17 (2008).

Schaaff, I., Heinisch, J. & Zimmermann, F. K. Overproduction of glycolytic enzymes in yeast. Yeast 5, 285–290 (1989).

Smits, H. P. et al. Simultaneous overexpression of enzymes of the lower part of glycolysis can enhance the fermentative capacity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 16, 1325–1334 (2000).

von Stockar, U., Maskow, T., Liu, J., Marison, I. W. & Patino, R. Thermodynamics of microbial growth and metabolism: an analysis of the current situation. J. Biotechnol. 121, 517–533 (2006).

Otero, J. M. Industrial systems biology and metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (PhD thesis, ISBN 978-91-7385-346-0) (Chalmers University of Technology, 2009).

Lange, H. C. et al. Improved rapid sampling for in vivo kinetics of intracellular metabolites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 75, 406–415 (2001).

de Koning, W. & van Dam, K. A method for the determination of changes of glycolytic metabolites in yeast on a subsecond time scale using extraction at neutral pH. Anal. Biochem. 204, 118–123 (1992).

Canelas, A. B. et al. Quantitative evaluation of intracellular metabolite extraction techniques for yeast metabolomics. Anal. Chem. 81, 7379–7389 (2009).

Piper, M. D. et al. Reproducibility of oligonucleotide microarray transcriptome analyses. An interlaboratory comparison using chemostat cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37001–37008 (2002).

Jansen, M. L. et al. Prolonged selection in aerobic, glucose-limited chemostat cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae causes a partial loss of glycolytic capacity. Microbiology 151, 1657–1669 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work has been conducted in the frame of the EU-funded project 'Yeast Systems Biology Network' (YSBN, contract number LSHG-CT-2005-018942), which partly funded this research. We also acknowledge the Chalmers Foundation, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and the EU-funded projects SYSINBIO and UNICELLSYS for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B.C. performed the fermentation experiments and assisted in data analysis and manuscript writing; N.H. constructed the strains under supervision of S.G.O.; A.F. assisted with the fermentation experiments and performed microarray analysis; J.v.d.B. assisted with the fermentation experiments and performed enzyme activity measurements; J.Z. performed integrated data analysis and assisted in manuscript writing; J.P.P. performed metabolome analysis and assisted with data analysis; K.v.E. and F.I.C.M. performed enzyme activity measurements and qPCR analysis; J.I.C. assisted in designing the strategy for comparison of different analytical methods and performed metabolome analysis. L.B., I.M., A.N., J.C.E. and P.C. performed metabolome analysis; A.C., D.D. and J.B. performed qPCR analysis; L.S. performed TRAC analysis; B.M.B., P.D.L., J.J.H., S.H., B.K., M.P., J.T.P., M.R., U.S., M.S.H., H.W., J.d.W., C.T.W., S.G.O. and J.N. designed and supervised the work; D.S. performed data analysis; D.P. coordinated activities; C.T.W. performed transcriptome data analysis; N.Z. coordinated metabolome analysis; J.N. wrote the paper and coordinated the activities; all authors were involved in editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Tables, Supplementary Notes, Supplementary Methods, Supplementary References

Supplementary Figures S1-S14, Supplementary Tables S1-S13, Supplementary Notes, Supplementary Methods, Supplementary References (PDF 2303 kb)

Supplementary Data 1

Comparison of enzyme activities measured at VUA versus DUT (XLS 25 kb)

Supplementary Data 2

Metabolite concentrations (XLS 88 kb)

Supplementary Data 3

Primers used for quantitative real time PCR (XLS 31 kb)

Supplementary Data 4

Threshold cycles for qPCR analysis (XLS 34 kb)

Supplementary Data 5

Analysis of housekeeping gene stability by qPCR (XLS 22 kb)

Supplementary Data 6

Probes used in TRAC analysis (XLS 26 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Canelas, A., Harrison, N., Fazio, A. et al. Integrated multilaboratory systems biology reveals differences in protein metabolism between two reference yeast strains. Nat Commun 1, 145 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1150

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1150

This article is cited by

-

Quantifying intracellular glucose levels when yeast is grown in glucose media

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Temporal segregation of biosynthetic processes is responsible for metabolic oscillations during the budding yeast cell cycle

Nature Metabolism (2023)

-

The metabolic growth limitations of petite cells lacking the mitochondrial genome

Nature Metabolism (2021)

-

LK-DFBA: a linear programming-based modeling strategy for capturing dynamics and metabolite-dependent regulation in metabolism

BMC Bioinformatics (2020)

-

Rewiring carbon metabolism in yeast for high level production of aromatic chemicals

Nature Communications (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.