Abstract

Synthetic cell-surface glycans are promising vaccine candidates against Clostridium difficile. The complexity of large, highly antigenic and immunogenic glycans is a synthetic challenge. Less complex antigens providing similar immune responses are desirable for vaccine development. Based on molecular-level glycan–antibody interaction analyses, we here demonstrate that the C. difficile surface polysaccharide-I (PS-I) can be resembled by multivalent display of minimal disaccharide epitopes on a synthetic scaffold that does not participate in binding. We show that antibody avidity as a measure of antigenicity increases by about five orders of magnitude when disaccharides are compared with constructs containing five disaccharides. The synthetic, pentavalent vaccine candidate containing a peptide T-cell epitope elicits weak but highly specific antibody responses to larger PS-I glycans in mice. This study highlights the potential of multivalently displaying small oligosaccharides to achieve antigenicity characteristic of larger glycans. The approach may result in more cost-efficient carbohydrate vaccines with reduced synthetic effort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

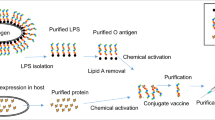

Immunologically active surface glycans expressed on bacterial, viral and parasitic pathogens are attractive vaccine targets1,2. Glycoconjugate vaccines consisting of isolated bacterial polysaccharides from Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis and Haemophilus influenzae linked to immunogenic carrier proteins save millions of lives each year2. However, isolated polysaccharides are heterogeneous, vary from batch to batch and can be obtained only for culturable pathogens2,3. Synthetic glycans provide an appealing alternative, as they are not limited to fermentable pathogens3,4,5,6 and allow for structure-based epitope design and refinement7,8,9,10. Still, the features of glycans that govern the production of protective and strong binding antibodies remain poorly understood9. Conventional glycan antigen design is a time-consuming trial-and-error process. Synthetic targets are selected based on biological repeating units of natural polysaccharides and immunologically evaluated in animal models10,11,12. If the resulting antibodies do not target the pathogen, different antigens are synthesized and tested. Vaccine antigens have to elicit antibodies of high affinity and/or avidity that are associated with disease protection2,13,14. Insights into the interactions of glycan antigens and antibodies are key for the rational design of synthetic carbohydrate vaccines8,9,15. Identifying minimal glycan epitopes, the smallest oligosaccharides recognized by antibodies, helps to reduce synthetic complexity en route to cost-efficient vaccines7,16. In recent times, a minimal tetrasaccharide epitope of the N. meningitidis serogroup W135 capsule was identified by chemical synthesis in conjunction with immunization studies17. The question whether multivalent display of minimal glycan epitopes of C. difficile may induce immune responses characteristic of larger glycans has not yet been answered.

We recently identified the minimal disaccharide α-L-Rha-(1→3)-β-D-Glc glycan epitope of the C. difficile polysaccharide-I (PS-I) surface polysaccharide, a promising vaccine target, by screening patient antibodies and murine immunization studies7. A vaccine against C. difficile is not yet available18 and limited expression of PS-I polysaccharide in bacterial cultures requires chemical synthesis to obtain glycan quantities sufficient for immunologic studies7,19,20,21,22. The synthetic repeating unit of PS-I, a branched pentasaccharide containing glucose and rhamnose19, is highly immunogenic, but its synthesis is laborious7,21,22. The disaccharide minimal epitope is easier to synthesize and can induce antibodies binding to larger PS-I structures, but is less immunogenic7. If linking of minimal disaccharides can mimic larger glycans, a new class of synthetic vaccine against C. difficile may result.

Here we show that disaccharides multivalently linked on a synthetic OAA scaffold23,24,25 are highly antigenic and induce antibodies to larger PS-I glycans in mice. Molecular-level insights into interactions of mono- and multivalent glycans with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were gained by combining glycan microarray, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), Interaction Map (IM), saturation transfer difference (STD)-NMR and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments. The mAbs mainly interacted with the terminal rhamnose and the adjacent glucose of the disaccharide. In the pentasaccharide, two disaccharides are connected by a glycosidic bond. This linkage does not directly participate in antibody binding, but increases the affinity from micromolar (disaccharide) to nanomolar (pentasaccharide), probably due to an entropy-driven process. Pentavalent display of disaccharides on an OAA scaffold lead to enhanced affinity to mAbs compared with monovalent glycans mainly through avidity effects. The pentavalent OAA equipped with a peptide T-cell epitope of the CRM197 immunogenic carrier protein26 was able to induce antibodies in mice that recognized larger PS-I glycans.

Our findings provide experimental proof that artificially connecting minimal glycan epitopes can mimic larger glycan structures (Fig. 1). This is a crucial step towards simplified synthesis of rationally designed antigens for vaccines against C. difficile and other pathogens expressing repetitive polysaccharide antigens.

During C. difficile infections (CDIs), patients mount antibodies to the PS-I polysaccharide. In efforts towards rationally designed vaccines, various PS-I glycan epitopes were synthesized7. A disaccharide minimal epitope (dashed lines) was identified from recognition patterns of human and mouse anti-PS-I antibodies7. (a) Mice immunized with a semi-synthetic glycoconjugate vaccine candidate of CRM197 and the disaccharide produce antibodies to the pentasaccharide repeating unit and smaller substructures. (b) A fully synthetic pentavalent glycan mimic with increased antigenicity compared with monovalent disaccharides elicits antibodies to the pentasaccharide only. It comprises an OAA backbone23,24,25 and a T-cell epitope, amino acids 366–383 of the CRM197 protein26.

Results

Pentasaccharide 1 elicits mAbs in mice

We recently described the syntheses of the C. difficile PS-I pentasaccharide repeating unit and oligosaccharide substructures7,22. The oligosaccharides were equipped with a reducing-end aminopentyl linker allowing for conjugation to carrier proteins and microarrays to study their immunologic properties (Fig. 2). Pentasaccharide 1 is the complete repeating unit of PS-I and disaccharide 3 is the minimal glycan epitope7.

To understand the structural determinants that mediate glycan–antibody interactions, we generated mAbs to PS-I with the hybridoma technique27 using a pentasaccharide 1-CRM197 glycoconjugate7, to immunize mice (Fig. 3a). Custom microarrays presenting 1, control oligosaccharides 7 and 8, the carrier protein CRM197 and a dummy conjugate representing the immunogenic spacer moiety of the glycoconjugate7 (Fig. 3b) were used to follow serum IgG responses. The mice produced IgG antibodies to 1, CRM197 and the spacer (Fig. 3c). Splenocytes of one selected mouse were used to obtain antibody-producing hybridomas27. Individual clones secreted IgG to either 1, CRM197 or the spacer moiety without apparent cross-reaction (Fig. 3d).

(a) Mice were immunized with pentasaccharide 1-CRM197 glycoconjugate7 at indicated time points. Sera were collected for glycan microarray-assisted evaluation of the immune responses. Splenocytes of one mouse were subjected to hybridoma cell fusion27. (b) Spotting pattern of glycan microarrays presented in c and d. Buffer was 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.5. Compound 1 was spotted at 0.1, 0.5 and 1 mM; CRM197 and the spacer dummy was spotted at 0.1, 0.5 and 1 μM; and 7 and 8 both at 1 mM. (c) Microarray scans representing the serum IgG response of one mouse. See Supplementary Fig. 1 for details. (d) Representative microarray scans of hybridoma cell supernatants of clone 5A9 producing antibodies to the spacer and 2C5 producing antibodies to PS-I.

Three hybridoma clones termed 2C5, 10A1 and 10D6 produced IgG exclusively binding to 1. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) of the purified mAbs showed expected light and heavy IgG chains, and no apparent protein impurities (Fig. 4a). The three mAbs were of the IgG1 subtype (Fig. 4b). Microarrays with PS-I oligosaccharide substructures were used to determine their binding specificities (Fig. 4c). Highest binding signals to 1 and weaker signals to rhamnose-containing substructures 2 and 3 were observed. mAb 10A1 also weakly bound to mono-rhamnose 4. No binding to oligoglucoses 5 and 6, or unrelated glycans 7 or 8 was seen (Fig. 4c,d). Based on these findings, we concluded that the requirements for anti-PS-I antibody binding were a terminal rhamnose that is 1→3 linked to a glucose, as present in glycans 1–3.

(a) SDS–PAGE analysis of the purified mAbs showing bands corresponding to heavy and light IgG chains. (b) Isotyping analysis of the three mAbs. (c) Spotting pattern and representative microarray scans of purified mAbs at 10 μg ml−1. See Supplementary Fig. 2 for details. (d) Glycan microarray-inferred binding signals to selected PS-I antigens (1–4) expressed as background-subtracted mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) are shown.

mAbs bind to 1 with nanomolar affinity

Kinetic SPR experiments were performed to determine the binding strengths of the mAbs to PS-I glycans expressed as dissociation constants (KD)8 (Fig. 5a). KD values to 1 were in the nanomolar (163–245 nM) (Fig. 5b) and those to 2 (13.3–18.8 μM) and 3 (5.9–37.5 μM) in the micromolar range (Fig. 5c). Weak or no binding was observed for mono-rhamnose 4 and oligoglucose 6. Overall, the SPR measurements (summarized in Table 1) confirmed results obtained by glycan microarray presented above.

(a) mAbs were captured with an anti-mouse IgG antibody immobilized on the SPR sensor surface. Glycan antigens were passed over the surface to monitor changes in the response unit signals8. (b,c) Representative sensorgrams showing reference-subtracted binding signals to 1 (b) and 3 (c). KD values were calculated by fitting the curves to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model (black overlaid curves) or with a steady-state affinity model (response units versus concentration plots). Indicated KD values are mean±s.e.m. of n=3 or mean with minimum and maximum values in parentheses of n=2 independent experiments. See Supplementary Figs 3–5 for details.

mAbs bind via terminal Rha and adjacent Glc

The glycan microarray and SPR data suggested the necessity of a terminal rhamnose and the adjacent glucose for antibody binding, whereas glucose moieties per se were immunologically inert. To understand antibody binding at molecular-level detail and to identify the functional groups involved in antibody binding, we performed STD-NMR measurements28. STD effects imposed by antibody binding to disaccharide 3 suggested that the main contact surface area was located within the terminal rhamnose, with highest STD effects at the indistinguishable methyl protons H6, H’6 and H’’6 (100% normalized STD effect), as well as H3 (99%) and H2 (78%) (Fig. 6a,b). The glucose moiety in 3 contributed weakly to antibody binding around H3 (11%). Despite the low saturation transfer, this interaction appears to be important for antibody binding, as mono-rhamnose 4 was not or only weakly bound by the mAbs in glycan microarray and SPR experiments. Comparison of STD-NMR spectra with 3 at a fixed saturation time indicated that all mAbs recognized a similar epitope (Fig. 6c). In addition, trisaccharide 2, which contains 3 and an additional glucose at the reducing end, showed comparable STD effects with mAb 10A1. This indicated that the additional glucose did not participate in binding and may explain similar binding affinities to 2 and 3 in SPR experiments described above.

(a,b) Recognition of disaccharide 3 by mAb 10A1 shown as Lewis structure and three-dimensional model calculated with Glycam70. Colours indicate percentages of STD effects28. (c) Recognition patterns of 3 by three mAbs. STD spectra were acquired at 2 s saturation transfer time in the presence of mAbs 2C5, 10A1 and 10D6 (from top to bottom). (d) Competition of trisaccharide 2 by pentasaccharide 1. Compound 2 exhibits STD effects on the same protons as 3 (middle panel). Addition of 1 resulted in the disappearance of the peaks imposed by 2, indicating competition for the same binding site (upper panel). The lower panel shows the reference spectrum.

Owing to the slow off-rates of 1 with all three mAbs, we were unable to determine any STD effects for the pentasaccharide. However, competition experiments of trisaccharide 2 with 1 completely diminished any STD effects imposed by 2 (Fig. 6d). This indicated identical binding sites and confirmed high-affinity binding of 1. Overall, STD-NMR data confirmed antibody binding to 1–3 and showed that interactions were mainly mediated by terminal rhamnoses with weak but essential participation of adjacent glucoses. This suggested that strong binding to 1 was proably achieved by linking two disaccharide 3 subunits via a glycosidic bond that does not interact directly with the antibodies.

mAb binding to 1 is entropically favoured

Pentasaccharide 1 was bound with about 100-fold lower KD values than the minimal glycan epitope 3. This stronger binding may have been due to avidity (re-binding) effects, as 3 is contained twice in 1, or by higher affinity. To address this question, we compared the binding properties by IM analysis based on SPR traces29. This data indicated that stronger antibody binding to 1 was mainly due to a higher on-rate of 126,000 M−1 s−1 compared with 250 M−1 s−1 for 3, whereas both off-rates were in the same range (Fig. 7a). Both antigens interacted with mAb 2C5 in a 1:1-like manner, indicated by one dominant peak in the IM plots. Therefore, stronger antibody binding to 1 was due to increased affinity, not avidity, which would be characterized by differences in off-rates and additional peaks29. This suggested that the binding pockets of anti-PS-I mAbs accommodated the entire pentasaccharide 1 and not just disaccharide 3, which could explain higher affinity to 1.

(a) IM analysis. The heat maps represent on- and off-rates of mAb 2C5 to 1 (upper) and 3 (lower). (b) Thermograms acquired using 7 μM of mAb 2C5 and titrating 250 μM of 1 (left) or 3 mM of 3 (right) at 25 °C. Thermodynamic parameters were inferred by nonlinear least-square fits of the data points. (c) Summary of thermodynamic parameters for 1 and 3 interacting with mAbs 2C5 and 10A1. Bars represent mean±s.e.m. of two independent measurements. See Supplementary Fig. 6 for details. (d) One-dimensional proton NMR spectrum, and 2D zTOCSY and NOE spectroscopy (NOESY) NMR spectra of 1 showing the coupled protons to the anomeric protons of the five residues with numbering according to the structure shown in e. Blue circles mark cross-peaks that appear in the NOESY spectrum, whereas not showing a corresponding peak in the zTOCSY. These peaks were marked as inter-residue NOEs and labelled by residue number and proton name. (e) Chemical structure (upper) and three-dimensional model of 1 obtained by using GLYCAM31,63 (lower). Glucose and rhamnose residues are highlighted blue and green, respectively. Dotted lines represent 23 inter-residue NOEs derived from a comparison of NOESY and zTOCSY spectra. All collected NOEs are within the 5-Å distance limit in the model structure (see Supplementary Table 1 for details).

Assuming that 1 had more interactions with the binding pockets, association with 1 would liberate more water molecules during complex formation than 3, thereby producing a more favourable entropy30. To investigate this, thermodynamic parameters of mAb interactions with 1 and 3 were measured by ITC (Fig. 7b). The binding stoichiometries for 1 were about two for mAbs 2C5 (2.2) and 10A1 (2.6), as expected for antibodies with two similar antigen-binding sites. For 3, the binding stoichiometry was set constant to 2, to fit the data points. Both 1–antibody and 3–antibody interactions were mainly enthalpically driven (Fig. 7c). Entropic contributions were favourable for 1, but considerably lower or slightly unfavourable for 3. The favourable entropic term of the 1–mAb 2C5 interaction was confirmed by SPR analysis that yielded similar thermodynamic parameters as ITC (Supplementary Fig. 6b,c). Therefore, entropically favoured binding was probably responsible for the increased affinity to 1, possibly because it provides more hydrophobic interactions through methyl groups of rhamnoses. The favourable entropic terms supported the notion that 1 fills the binding pocket of the mAbs.

IM analysis indicated that binding stoichiometries for 1 and 3 were identical, despite the fact that 1 contains two copies of 3. Therefore, the mAb binding pockets probably do not provide two identical binding sites for 3, but one binding site for 1 that may adopt a more complex conformation. To obtain structural insight into the conformation of 1, two-dimensional (2D) NMR spectroscopy was employed (Fig. 7d). Inter-residue nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs) were all in agreement with a model of the solution structure of 1 based on calculations using the GLYCAM06 force field31 (Fig. 7e). These data suggested that 1 adopts a conformation in which the two units of 3 are oriented in an angled position relative to each other. Taken together, IM, ITC and 2D NMR experiments indicated that the mAb binding pockets accommodate 1, whereas 3 made fewer contacts, resulting in lower binding affinity.

Compound 11 shows high-avidity mAb binding

The results indicated that high-affinity antibody binding to PS-I was achieved by covalently linking two disaccharides 3 that together adopt a specific conformation fitting into the mAb binding pockets. As the connecting glycosidic bond is not directly involved in antibody binding, this linker may be replaced with a synthetic scaffold to mimic larger PS-I structures. To investigate this, a synthetic oligomer displaying five disaccharide units was synthesized using a derivative of 3 with a reducing end thioethyl linker 9 (see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 8 for the synthesis). Two disaccharide-functionalized OAAs25 were prepared: monovalent 10 and pentavalent 11 (Supplementary Fig. 7a).

First, we tested whether the thiol group influenced antibody binding using SPR. In line with the STD-NMR observations that the linker at the reducing end of 3 did not participate in antibody binding, 9 bound to mAb 2C5 with comparable kinetics and affinity (Supplementary Fig. 7b). The KD values for 9 and 3 were highly similar (15.1 and 18 μM, respectively). Dose-dependent antibody binding to the monomeric construct 10 was also detected (Supplementary Fig. 7c). Owing to slow on-rates, perhaps resulting from steric constraints, binding curves did not reach equilibrium states, impeding KD value calculation for 10. However, the off-rates were similarly fast as observed for 3 and 9. Slow on-rates were also seen for the pentavalent construct 11–mAb interaction, but off-rates were considerably lower (Fig. 8a), indicating increased avidity to 11 compared with 10.

(a) SPR sensorgrams of mAb 2C5 binding to construct 11 that pentavalently presents the minimal disaccharide glycan epitope. For comparison, sensorgrams of the same antibody to disaccharide 3 and pentasaccharide 1 are shown. Avidities were estimated by fitting off-rate curves with a dissociation model (black dashed lines). The off-rate values koff are mean±s.e.m. of n=3 or mean with minimum and maximum values in parentheses of n=2 independent measurements. (b) Mice were immunized with 11 (group 1) or glycoconjugate 12 (group 2) at the indicated time points. (c) Glycan microarray-inferred serum IgG levels to 1 (upper) and 3 (lower) of immunized mice expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values. Bars represent mean+s.d. of three mice. Values of individual mice are shown as black dots. (d) SPR-inferred serum antibody responses to 1 (upper) and 3 (lower) in immunized mice. The experimental set-up is shown to the left. Average sensorgrams (two independent measurements) of pooled sera at week 5 post immunization subtracted by week 0 signals are shown in the centre. The bar graphs on the right show response unit signals at t=290 s (mean+s.e.m. of two independent measurements). See Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Figs 11–13 for details on the data presented in b–d.

To compare avidities, we used SPR to estimate the off-rates, which are the major determinants of antibody binding strength13,32,33,34,35,36,37. The off-rate of the 11–mAb 2C5 interaction was 2.8 × 10−8 s−1 (Fig. 8a), whereas off-rates of 1, 3 and 10 (Supplementary Fig. 7c) were about five orders of magnitude faster (1.9, 1.6 and 1.4 × 10−3 s−1, respectively). This demonstrated increased avidity to the pentameric compared with the monomeric construct. Tight antibody binding to OAA 11 demonstrated that antigenicity of larger PS-I structures could be mimicked by covalent linking of minimal glycan epitopes 3 on a synthetic scaffold.

Compound 11 elicits antibodies to larger glycans

We next sought to investigate the ability of 11 to induce antibodies in mice. A group of mice was immunized with 11 three times in 2-week intervals (Fig. 8b). To be able to recruit T-cell helpers, 11 was equipped with a T-cell epitope encompassing amino acid residues 366–383 of the CRM197 protein26. Thereby, 11 represents a fully synthetic, multivalent vaccine candidate. For comparison, another group of mice was subjected to an identical immunization regime with glycoconjugate 12 composed of 3 and CRM197 (Supplementary Fig. 10a and Supplementary Note 2) that represents a semi-synthetic vaccine candidate. Serum IgG responses to the disaccharide 3 and pentasaccharide 1 were followed by glycan microarray (Fig. 8c) and SPR measurements (Fig. 8d). Most interestingly, 11 elicited IgG exclusively to 1, whereas antibodies induced by 12 recognized both 3 and 1. The latter observation confirmed previous results obtained with a comparable glycoconjugate of 3 and the CRM197 protein7. Both groups of mice also produced IgGs to mono-rhamnose 4, as seen in our previous immunization studies with PS-I-CRM197 glycoconjugates7, and to CRM197, confirming the functionality of the synthetic CRM197 peptide in 11 (Supplementary Fig. 11). Although antibodies to CRM197 were detected in all mice after immunization, glycan-specific IgGs were only detected in one or two mice per group, indicating limited antigenicity of the glycan antigens (Fig. 8c). Next, we investigated whether the ability of 11 to elicit glycan-specific IgGs could be increased through its conjugation to CRM197, to furnish glycoconjugate 13 (Supplementary Fig. 10b and Supplementary Note 2). Although immunization of mice with 13 lead to glycan-specific IgGs to mono-rhamnose 4 only, an existing IgG response to 1 and 3 elicited by two immunizations of 12 could be boosted with 13. Collectively, the immunization experiments showed that fully synthetic 11 was able to elicit IgGs to pentasaccharide 1 in mice at comparable levels to the semi-synthetic glycoconjugate 12.

Discussion

PS-I surface glycans are promising immunogens for vaccines against C. difficile7,18,19,20,21,22. We recently identified PS-I oligosaccharides that are recognized by antibodies of patients and therefore represent natural epitopes7. The disaccharide Rha-(1→3)-Glc 3 emerged as the smallest antigenic glycan and consequently provided a useful template for vaccines with low synthetic effort. However, its ability to raise antibodies in a conventional semi-synthetic glycoconjugate was limited7, calling for alternative means of presentation. Previous studies have shown that the multivalent display of small glycan antigens can yield highly immunogenic structures38. For instance, multivalently presented Tn monosaccharide antigens (α-N-acetylgalactosamine-serine) on dendrimeric39 or cyclic40 peptides were able to elicit high levels of anti-Tn antibodies in mice. This suggested that the multivalent display of PS-I disaccharides may lead to enhanced capability of inducing glycan-specific antibodies.

The feasibility of this approach required an understanding of how PS-I glycans interact with mammalian antibodies. Therefore, we studied glycan interactions with anti-PS-I mAbs using various biochemical and biophysical methods. Glycan microarray and SPR studies confirmed that disaccharide 3 is the minimal epitope of the PS-I glycan7. However, mAb binding to the more antigenic pentasaccharide 1 was stronger with nanomolar KD values compared with 3 with micromolar KD values. STD-NMR measurements revealed that mAb binding to PS-I glycans was primarily mediated by terminal rhamnoses and adjacent glucoses, but did not extend further into the antigens. The glycosidic bond that links two units of 3 in the pentasaccharide 1 does not directly participate in binding events. It may therefore be replaced by a linker to furnish structures that can mimic the immunologic properties of larger PS-I glycans. Molecular interaction studies indicated that stronger mAb binding to 1 was due to higher affinity, not avidity, despite the presence of two units of 3 in the pentasaccharide. ITC studies suggested that the entire pentasaccharide is accommodated by the binding pockets of the mAbs, leading to entropically favoured interactions. 2D NMR experiments showed that the pentasaccharide probably adopts a conformation with two disaccharide units in an angled position. Multivalently displayed disaccharides 3 might therefore lead to enhanced antibody binding through increased affinity (faster on-rates) when two adjacent disaccharides adopt a conformation similar to the pentasaccharide, through increased avidity (slower off-rates) by re-binding events, or a combination of both.

To investigate this, we synthesized OAAs multivalently presenting 3. The OAA backbone has been shown to be non-toxic, non-immunogenic and suitable for the multivalent presentation of oligosaccharides with comparably low synthetic effort23,24,25. Straightforward solid-phase synthesis of OAAs furnished the PS-I glycan mimic 11 displaying five disaccharides 3. This corresponds to 2.5 generic copies of the pentasaccharide, thereby enabling a combination of potential affinity- and avidity-enhancing effects. A comparably large construct was also chosen, as larger PS-I glycans tend to be more capable of eliciting antibodies than smaller ones7. Tight mAb binding to 11 was shown by SPR. Owing to slow on-rates that were outside of the measurable range, we were unable to detect whether affinity was increased. However, the off-rates were about five orders of magnitude slower than for monovalent disaccharides, indicating strong avidity effects. Thereby, we successfully created a PS-I glycan mimic showing high-avidity antibody binding. This is reminiscent of natural repetitive polysaccharides that enable strong antibody binding through avidity effects despite usually low affinities to individual epitopes2.

To investigate the ability of 11 to induce PS-I-specific antibodies, we performed immunization studies in mice. Compound 11 was equipped with a peptide epitope of CRM197 to recruit T-cell helpers, similar to previous immunization efforts with multivalent Tn antigens that included synthetic T-cell epitopes39,40. Antibody responses were compared with the semi-synthetic glycoconjugates 12 and 13 obtained by covalently linking 3 and 11, respectively, to CRM197. The glycoconjugates were synthesized using a di-p-Nitrophenyl adipate ester spacer molecule41, to facilitate the challenging conjugation of 11 to CRM197, as this chemistry is more efficient than the previously7 used di-N-succinimidyl adipate ester.

Immunization of mice with fully synthetic OAA 11 induced IgGs to pentasaccharide 1 at low but comparable levels to semi-synthetic glycoconjugate 12. Interestingly, in contrast to 12, IgGs to disaccharide 3 were not detectable after immunization with 11. Therefore, the IgG response to 11 was more specific to larger PS-I glycans, which is desirable for a vaccine to limit cross-reaction with structurally related glycans. This also indicated that two adjacent disaccharides in 11 may have adopted a conformation that resembles the pentasaccharide to some degree.

To investigate whether the ability of 11 to induce PS-I-specific antibodies could be enhanced, we conjugated the pentavalent construct to CRM197. The resulting glycoconjugate 13, however, was unable to generate PS-I glycan-specific IgGs in mice, probably due to the low antigen loading of 1.3 mol of 11 per mole of CRM197. It has been noted previously that low antigen loading of glycoconjugates is associated with weaker antibody responses42. Glycoconjugate 13, however, was able to boost existing IgG responses to PS-I glycans elicited by 12, suggesting limited ability to raise antibodies that may be increased by higher antigen loading.

It has to be mentioned that the PS-I-specific IgG responses induced by 12, displaying antigens at a high density (20 mol 3 per mole of CRM197) were relatively weak and only detectable at low serum dilutions (1:20) by glycan microarray. A comparable glycoconjugate with lower antigen density (10 mol 3 per mole of CRM197) investigated previously7 elicited higher levels of PS-I-specific IgGs in mice than 12 that were detectable at higher dilutions (1:100). It has been suggested previously that too high glycan loading of glycoconjugates may limit T-cell stimulation, resulting in weak antibody responses42. Higher antigen loading and therefore weaker IgG levels in the present study probably resulted from the employed conjugation chemistry. Still, glycoconjugate 12 was suitable to compare antigen recognition patterns to mice immunized with 11, as 12 elicited IgGs cross-reacting to 1 and 3, similar to our previous immunization studies7. Further studies are required to increase the ability of multivalently displayed disaccharides to elicit antibodies. As the linker itself is not involved in antibody binding, it may be replaced to alter the distance of disaccharide units, the biocompatibility and/or the flexibility of the construct. Comparative studies with constructs of different valencies may help to differentiate affinity from avidity effects. The antibody response to multivalent glycan mimics on immunization may also benefit from incorporation of immune stimulatory molecules such as glycosphingolipids, as we have shown recently43. Furthermore, the ability of the anti-PS-I antibodies to confer functional immunity requires investigation. Both active immunization and passive antibody transfer regimes are currently being tested for their ability to limit C. difficile-induced colitis in a murine challenge model. Chimerized and humanized versions of the mAbs will be designed that may be of potential therapeutic use.

In a broader sense, our findings provide insights into the nature of glycan–antibody interactions. Similar to lectins, antibody binding to glycan antigens is mainly an enthalpically driven process often of low millimolar to micromolar affinities44,45,46,47,48,49,50 and, in most cases, characterized by unfavourable entropic contributions45,46,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58. Enthalpy–entropy compensation usually impedes high-affinity binding. Nanomolar affinities of antibodies against oligosaccharides are typically attributed to strong ionic interactions as in the case of a trisaccharide antigen of Chlamydia59,60 or to the conformational rigidity of larger polysaccharides that leads to favourable entropic contributions due to the lower entropic penalty during antibody binding61. In contrast, we here demonstrated antibodies binding with nanomolar affinity to a comparably small oligosaccharide antigen, pentasaccharide 1, without charged residues. Details on these interactions were obtained by STD-NMR. This technique has been used to explain glycan selectivity of lectins at the molecular level62 and is also useful to decipher glycan–antibody interactions8. High-affinity binding to 1 could be due to antibody interactions with hydrophobic methyl groups, as shown by STD-NMR, which result in a favourable entropy by solvent displacement. Interestingly, although the number of mAbs in this study was limited, all three recognized the similar molecular epitope of PS-I mainly involving rhamnose. The notion that antibody affinity benefits from recognition of hydrophobic methyl groups in bacterial sugars is further supported by our recent observation that methyl groups of anthrose and rhamnose contribute significantly to nanomolar affinity antibody binding to a tetrasaccharide antigen of Bacillus anthracis9. The avidity-enhancing effect of presenting minimal glycan epitopes on a scaffold may also explain how repetitive bacterial polysaccharides can induce strongly binding antibodies, despite usually low affinities against single epitopes.

Overall, this study shows that the identification and multivalent presentation of minimal glycan epitopes can result in fully synthetic, highly antigenic glycan mimics that are able to elicit antibody responses specific for larger glycans. More generally, the findings advance our understanding of glycan–antibody interactions that are the basis for epitope-focused rational antigen design en route towards improved glycan-based vaccines against C. difficile and other pathogens expressing repetitive glycan antigens.

Methods

Preparation of glycan microarrays

Oligosaccharides bearing an amine-terminal linker, or proteins, were immobilized on N-hydroxyl succinimide ester-activated slides (CodeLink Activated Slides by SurModics, Inc., Eden Prairie, MN, USA) with a piezoelectric spotting device (S3; Scienion, Berlin, Germany) in such a way that 64 individual subarrays were contained each slide27. Microarray slides were incubated in a humid chamber for 24 h at room temperature (RT) to complete coupling reactions. Next, the remaining N-hydroxyl succinimide ester groups were quenched with 50 mM aminoethanol solution pH 9 for 1 h at 50 °C, washed three times with deionized water and stored desiccated until use, as described27.

Generation of mAbs

mAbs to immunogen 1 were obtained by the hybridoma technique27 from mouse splenocytes immunized with a glycoconjugate composed of the CRM197 carrier protein (Pfénex, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and 1 synthesized with di-N-succinimidyl adipate as cross-linking reagent7. Six 6–8 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice (purchased from Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany) were immunized with this glycoconjugate via the subcutaneous route in the presence of aluminium hydroxide adjuvant (Alum Alhydrogel, Brenntag) three times in 2-week intervals. Each immunization contained 3 μg of CRM197-bound immunogen 1. The immune response was followed weekly by glycan microarray-assisted analysis of sera for IgG antibodies to 1, CRM197 and the generic spacer moiety composed of aminopentyl and adipoyl moieties, and control oligosaccharides. For serum IgG analysis, printed and quenched microarray slides were blocked for 1 h with 1% (w/v) BSA in PBS, washed three times with PBS and dried by centrifugation (300 g, 5 min). Slides were then equipped with 64-well incubation chambers (FlexWell 64, Grace Bio-Labs, Bend, OR, USA) and incubated with mouse sera diluted 1:100 (v/v) in PBS for 1 h in a humid chamber. After washing three times with 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS (v/v) and drying by centrifugation, the microarray slides were incubated for 1 h with anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 647 antibody (Life Technologies, catalogue number A-31574) diluted 1:400 in 1% BSA in PBS (w/v) in a humid chamber. After washing three times with 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS (v/v) and once with deionized water, microarray slides were dried by centrifugation and scanned with a GenePix 4300A microarray scanner (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Of the six mice, the one with highest IgG response to 1 was selected for splenocyte isolation 1 week after the third immunization and splenocytes were fused with P3X63Ag8.653 myeloma cells (purchased from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA), to obtain hybridomas. Hybridoma clones were selected by glycan microarray-assisted analysis27. After three subsequent subcloning steps, three hybridoma clones, 2C5, 10A1 and 10D6, producing IgGs exclusively to 1 were recovered.

Purification and isotype analysis of mAbs

Hybridoma clones 2C5, 10A1 and 10D6 were expanded in serum-free medium as described27. Cell culture supernatants were concentrated tenfold using centrifugal filter devices with 50 kDa exclusion volume (Amicon Ultra-15 Ultracel, Millipore). Concentrated supernatants were subjected to IgG purification using the Proteus Protein G Antibody Purification Midi Kit (AbD Serotec) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Purified mAbs were stored in PBS with 0.02% (w/v) sodium azide at 4 °C. Protein concentrations were determined with the Pierce Micro BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific) and IgG isotypes were determined with the AbD Serotec Mouse Isotyping Kit MMT1 according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

SDS-PAGE

Samples were dissolved in Lämmli buffer (0.125 M Tris, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 4% (w/v) SDS, 5% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol and bromophenol blue pH 6.8) and boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. Samples were run in a 10% polyacrylamide gel and stained with 0.025% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 in an aqueous solution containing 40% (v/v) methanol and 7% (v/v) acetic acid. Gel was destained with 50% (v/v) methanol and 10% (v/v) acetic acid in H2O. PageRuler Plus Prestained Protein Ladder (Thermo Scientific, catalogue number 26619) served as size marker.

Glycan microarray binding assays

Microarray slides were blocked with 1% BSA in PBS (w/v) for 1 h at RT, washed three times with PBS and dried by centrifugation (300 g, 5 min). FlexWell 64 incubation chambers (Grace Bio-Labs) were applied to microarray slides. Slides were incubated with mouse sera diluted 1:100 with PBS unless mentioned otherwise, in a humid chamber for 1 h at RT, washed three times with 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS (v/v) and dried by centrifugation (300 g, 5 min). Slides were incubated with fluorescence-labelled secondary antibodies diluted 1:400 in 1% BSA in PBS (w/v) in a humid chamber for 1 h at RT, washed three times with 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS (v/v), rinsed once with deionized water and dried by centrifugation (300 g, 5 min) before scanning with a GenePix 4300A microarray scanner (Molecular Devices). Image analysis was carried out with the GenePix Pro 7 software (Molecular Devices). The photomultiplier tube voltage was adjusted such that scans were free of saturation signals. Background-subtracted mean fluorescence intensity values were exported to Microsoft Excel, for further analyses. Secondary antibodies used were as follows: Alexa Fluor 647 Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) (Life Technologies, catalogue number A-31574) and Alexa Fluor 594 Goat Anti-Mouse IgG1 (γ1) (Life Technologies, catalogue number A-21125).

SPR and IM analysis

Binding analyses were carried out on a Biacore T100 instrument (GE Healthcare). CM5 sensor chips were functionalized with about 10,000 RUs of α-mouse IgG capture antibody, using the Mouse Antibody Capture Kit and the Amine Coupling Kit (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. A blank-immobilized flow cell was used as reference, to compensate for nonspecific binding of antibodies or oligosaccharides to the sensor chip surface. Kinetic measurements were performed with the Biacore T100 Control software using the ‘Kinetics’ function. PBS was used as running buffer and all measurements were performed at 25 °C and a flow rate of 30 μl min−1. About 500 RUs of mAbs were captured at a concentration of 50 μg ml−1 diluted in PBS and oligosaccharides or OAAs (in PBS) at the indicated concentrations were passed through, using the standard parameters for association and dissociation times unless mentioned otherwise. Flow cells were regenerated with 10 mM glycine-HCl pH 1.7 for 30 s. Kinetic evaluation of binding responses was performed with the Biacore T100 Evaluation software, using reference-subtracted sensorgrams. Two different kinetic models, a 1:1 binding Langmuir model and a two-state reaction model, which assumes a conformational change in the antibody–analyte complex, were used to fit the data. The fitting quality was evaluated by investigating respective residual plots, χ2 and s.e. values for on- and off-rates. Both models yielded similar good fittings. We chose the 1:1 binding model over the two-state reaction model to calculate on- and off-rates, as well as KD values, as this model makes fewer assumptions. When on-rates and/or off-rates were outside of the measurable ranges of the instrument, the steady-state affinity model was used instead to determine KD values. The 1:1 binding model was generally preferred over the steady-state affinity model in cases where both could be applied. In these cases, the two models yielded roughly similar KD values. Thermodynamic parameters were inferred by using the ‘Thermodynamics’ function of the Biacore T100 Control software with the same experimental set-up described above. Temperatures from 13 to 37 °C were chosen. Values for ΔG, ΔH and ΔS were inferred by van’t Hoff analysis. IM analysis was carried out by Ridgeview Diagnostics AB, Uppsala, Sweden.

STD-NMR

Before the STD-NMR studies, proton resonances of oligosaccharides 1–3 were assigned using standard one-dimensional proton spectra, as well as 2D total correlation spectroscopy (2D-TOCSY), correlation spectroscopy, 1H–13C heteronuclear single quantum coherence and 1H–13C heteronuclear multiple bond correlation spectra at concentrations varying between 5 and 20 mM in D2O. All NMR studies were measured at 298 K on a Varian PremiumCOMPACT 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a OneNMR probe. For STD-NMR, samples contained 200 μM ligand and 2 μM antibody in 40 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0, uncorrected). On-resonance irradiation was set to −0.5 p.p.m. and off-resonance irradiation was set to 80 p.p.m. A 35-ms T1ρ spin-lock filter and a W5 WATERGATE for solvent suppression were applied. The saturation pulse train consisted of a series of Gaussian shaped pulses of 50 ms duration and 1 ms interpulse delay with an irradiation power of 85 Hz. A total of 2,048 scans were recorded. STD-NMR spectra of carbohydrates in the absence of antibody and spectra of antibody only served as negative controls. Here, saturation and relaxation times were set to 2 and 6 s, respectively. STD build-up curves for mAb 10A1 were recorded at saturation transfer times of 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 6 s, adjusting the prescan delay accordingly. Epitopes for mAbs 2C5 and 10D6 were recorded with a saturation transfer time of 2 s. NMR spectra were processed in MestReNova 9.1 (MestreLab) and data were analysed in OriginPro9 (OriginLab) to obtain the binding epitopes according to Mayer and James28. For the competition experiments, 1 was added to samples of 3 or 2 to a final concentration of 200 μM applying a saturation transfer time of 2 s.

ITC

All measurements were performed in a MicroCal ITC200 system (GE Healthcare) at 25 °C. Oligosaccharides 1 and 3 (in PBS) at either 250 μM or 3 mM were titrated into the measurement cell containing 7 μM of mAb 2C5 or 10A1 in PBS (injection volume 2 μl). Data analysis was performed with the OriginPro 8.6G software (MicroCal) provided with the instrument, using the one set of site model to fit the data points to infer thermodynamic parameters and stoichiometry values. For the low c-value measurements for 3, the stoichiometry was set constant to 2.

Conformation of 1 as determined by NMR and modelling

Solution conformation of 1 was investigated by 2D-TOCSY and NOE spectroscopy NMR experiments. Compound 1 was dissolved in D2O at 5.7 mM and spectra were obtained at 298 K. The NOE spectroscopy spectrum was acquired at 500 ms mixing time, 512 increments in f1 at 16 scans per increment with an acquisition time of 0.57 s, an inter-scan delay of 2 s and a zero-quantum filter. The corresponding zTOCSY was acquired with the same settings as above using four scans and a DIPSI2 spinlock with a mixing time of 120 ms. Data were processed in MestreNova 9.0 (MestreLab). Solution structure of 1 was calculated using GLYCAM06 force field31 and analysed with UCSF Chimera package63.

Synthesis of oligosaccharide-functionalized OAAs

OAA building block synthesis and solid phase assembly of the oligomeric backbone was performed following previously established protocols25. Conjugation of 9 was performed in batch starting from a solution of acetonitrile, water, acetic acid, radical initiator and tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, which was carefully degassed and added to lyophilized oligomer precursors and 9. Conjugation reactions were performed in a standard transparent HPLC vial (1.5 ml) and were irradiated for 18 h using an ExoTerra ReptiGlo 5.0 UVB 26 W terrarium lamp (compound 10, radical initiator: benzophenone) or a Heraeus TQ 150, 150 W medium-pressure mercury lamp (compound 11, radical initiator: 4,4-Azobis(4-cyanovaleric acid))64. After ultraviolet irradiation, the reaction mixture was purified by reversed-phase HPLC (compound 10) or size-exclusion chromatography using Sephadex G-25 (compound 11). The resulting conjugates were obtained as partially or fully oxidized sulfoxide-linked products (Supplementary Fig. 9). Reversed-phase HPLC chromatograms of 10, 11 and their precursors are shown in Supplementary Fig. 14. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight mass spectra of both precursors are shown in Supplementary Fig. 15. A short peptide sequence comprising amino acids 366–383 of the CRM197 protein26 was introduced to recruit T-cell helpers for immunization experiments.

Preparation of glycoconjugates 12 and 13

Conjugation reactions followed a protocol modified from Wu et al.41 In brief, to obtain 12, 2.2 mg of disaccharide 3 (5.3 μmol) were reacted with sixfold molar excess of homobifunctional adipic acid p-nitrophenyl ester (see Supplementary Fig. 10a) in dimethyl sulfoxide/pyridine (2:1) in the presence of Et3N for 2 h at RT. Excess linker was removed by washing with dichloromethane/diethylether (1:1). This yielded 2.6 mg the half ester shown in Supplementary Fig. 10a (74% yield). A quantity of 1.4 mg (2.1 μmol) of half ester were reacted with 2 mg (34.2 nmol) of CRM197 (Pfénex) in 100 mM sodium phosphate pH 8 for 24 h at RT. To obtain 13, 380 μg of construct 11 (71.3 nmol) were reacted with sixfold molar excess of spacer in dimethyl sulfoxide/pyridine (2:1) in the presence of Et3N for 2 h at RT. Excess linker was removed by washing with dichloromethane/diethylether (1:1). This yielded 230 μg of the half ester shown in Supplementary Fig. 10b (58% yield). Two hundred and thirty micrograms of this half ester were reacted with 0.5 mg (8.6 nmol) of CRM197 in 100 mM sodium phosphate pH 8 for 24 h at RT. After the reactions, both glycoconjugates were desalted and concentrated with ddH2O, using centrifugal filter devices with an exclusion volume of 10,000 Da (Amicon Ultracel, Millipore). Protein concentrations were determined by measuring the absorbance at a wavelength of 280 nm in a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), employing an extinction coefficient of 54,320 M−1 cm−1.

Western blottings

Proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE as described above and electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Ponceau S staining was performed to confirm successful transfer. After washing to remove the Ponceau stain, polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were blocked with TBS-T (Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20) supplemented with 5% (w/v) skimmed milk powder. The CRM197 protein was immunolabelled with goat anti-diphtheria toxin antibody (Abcam, catalogue number ab19950) diluted 1:2,500 in TBS-T with 1% (w/v) BSA and detected with anti-goat IgG horseradish peroxidase conjugate antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, catalogue number A4174) diluted 1:5,000 in TBS-T with 1% (w/v) BSA after three washing steps with TBS-T. PS-I glycans were immunolabelled with a mixture of mAbs 2C5, 10A1 and 10D6, each at 2.5 μg ml−1 in TBS-T with 1% (w/v) BSA and detected with anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase conjugate antibody (Dianova, catalogue number 115-035-062) diluted 1:10,000 in TBS-T with 1% (w/v) BSA after three washing steps with TBS-T. Chemoluminescence was detected using the Amersham ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, in a LAS-4000 imager (Fujifilm).

Carbohydrate concentration determination by anthrone assay

Anthrone reactions followed a modified protocol by Turula et al.65 To 35 μl of a 0.1% (w/v) solution of anthrone reagent (Sigma) in concentrated (98%) sulfuric acid, 5 μl of desalted solutions of 12, 13 or CRM197 were added in 96-well round-bottom microtitre plates. Absorbance at 579 nm was determined in a spectrophotometric plate reader and compared with standard curves using equimolar amounts of D-glucose and L-rhamnose. Such, average antigen-to-CRM197 molar ratios were calculated. For 12 and 13, this yielded 20 mol of 3 and 1.3 mol of 11 (equal to 6.5 mol of 9) per mole of CRM197, respectively.

Immunizations

Six- to eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River. Mice were immunized subcutaneously with different immunization regimes three times in 2-week intervals with an amount of construct 11 corresponding to 5 μg glycan antigen or glycoconjugates 12 and 13 (1 μg glycan antigen). Three mice per group were chosen, as this study aimed to qualitatively assess whether compounds 11–13 were capable of eliciting antibodies, without intention of quantitatively comparing antibody levels. Therefore, no randomization or blinding was required. Freund’s Adjuvant (Sigma) was used for all immunizations according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Complete Freund’s Adjuvant was used for initial immunizations at week 0 and Incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant was used for subsequent immunizations at weeks 2 and 4. Animal experiments were approved by the Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales, Berlin, and performed in strict accordance with the German regulations of the Society for Laboratory Animal Science and the European Health Law of the Federation of Laboratory Animal Science Associations. All efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Determination of serum antibody responses by SPR

Antibody binding analyses were carried out on a Biacore T100 instrument (GE Healthcare). Flow cells of a CM5 sensor chip were immobilized with 1 mM solutions of pentasaccharide 1 (final response 390.5 RU) or disaccharide 3 (247.5 RU) in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 8.5, using the Amine Coupling Kit (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Flow cells immobilized with about 10,000 RU of BSA served as reference. Kinetic measurements with mouse sera diluted 1:100 in PBS were performed with the Biacore T100 Control software, using the standard parameters of the ‘Kinetics’ function but with extended contact and dissociation times of 300 s. PBS was used as running buffer and all measurements were performed at 25 °C and a flow rate of 30 μl min−1. Binding signals of pooled (n=3 mice) post-immunization (week 5) sera were subtracted by pre-immunization (week 0) sera signals. Binding curves were extracted for further analysis in Microsoft Excel. The binding signals at t=290 s contact time served as antibody binding signal.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Broecker, F. et al. Multivalent display of minimal Clostridium difficile glycan epitopes mimics antigenic properties of larger glycans. Nat. Commun. 7:11224 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11224 (2016).

References

Wang, D. in Encyclopedia of Molecular Cell Biology and Molecular Medicine, II ed. Meyers R. A. 277–301 (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany, 2004).

Astronomo, R. D. & Burton, D. R. Carbohydrate vaccines: developing sweet solutions to stick situations? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 308–324 (2010).

Hecht, M. L., Stallforth, P., Silva, D. V., Adibekian, A. & Seeberger, P. H. Recent advances in carbohydrate-based vaccines. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 13, 354–359 (2009).

Lepenies, B. & Seeberger, P. H. The promise of glycomics, glycan arrays and carbohydrate-based vaccines. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 32, 196–207 (2010).

Lepenies, B., Yin, J. & Seeberger, P. H. Applications of synthetic carbohydrates to chemical biology. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 14, 404–411 (2010).

Seeberger, P. H. & Werz, D. B. Synthesis and medical applications of oligosaccharides. Nature 446, 1046–1051 (2007).

Martin, C. E. et al. Immunological evaluation of a synthetic Clostridium difficile oligosaccharide conjugate vaccine candidate and identification of a minimal epitope. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 9713–9722 (2013).

Broecker, F. et al. Epitope recognition of antibodies against a Yersinia pestis lipopolysaccharide trisaccharide component. ACS Chem. Biol. 9, 867–873 (2014).

Oberli, M. A. et al. Molecular analysis of carbohydrate-antibody interactions: case study using a Bacillus anthracis tetrasaccharide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 10239–10241 (2010).

Anish, C., Schumann, B., Pereira, C. L. & Seeberger, P. H. Chemical biology approaches to designing defined carbohydrate vaccines. Chem. Biol. 21, 38–50 (2014).

Robbins, J. B. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and immunogenicity in mice of Shigella sonnei O-specific oligosaccharide-core-protein conjugates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 7974–7978 (2009).

Safari, D., Rijkers, G. & Snippe, H. in The Complex World of Polysaccharides ed. Karunaratne D. N. 617–634InTech (2012).

Khurana, S. et al. MF59 adjuvant enhances diversity and affinity of antibody-mediated immune response to pandemic influenza vaccines. Sci. Transl. Med. 3, 85ra48 (2011).

Steward, M. W. & Chargelegue, D. in Handbook of Experimental Immunology 5th edn eds Weir D. M., Herzenberg L. A., Blackwell C. C. 38.1–38.36Blackwell (1997).

Serruto, D. & Rappuoli, R. Post-genomic vaccine development. FEBS Lett. 580, 2985–2992 (2006).

Bundle, D. R., Nycholat, C., Costello, C., Rennie, R. & Lipinski, T. Design of a Candida albicans disaccharide conjugate vaccine by reverse engineering a protective monoclonal antibody. ACS Chem. Biol. 7, 1754–1763 (2012).

Wang, C. H. et al. Synthesis of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup W135 capsular oligosaccharides for immunogenicity comparison and vaccine development. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 52, 9157–9161 (2013).

Rebeaud, F. & Bachmann, M. F. Immunization strategies for Clostridium difficile infections. Expert Rev. Vaccines 11, 469–479 (2012).

Ganeshapillai, J., Vinogradov, E., Rousseau, J., Weese, J. S. & Monteiro, M. A. Clostridium difficile cell-surface polysaccharides composed of pentaglycosyl and hexaglycosyl phosphate repeating units. Carbohydr. Res. 343, 703–710 (2008).

Bertolo, L. et al. Clostridium difficile carbohydrates: glucan in spores, PSII common antigen in cells, immunogenicity of PSII in swine and synthesis of a dual C. difficile-ETEC conjugate vaccine. Carbohydr. Res. 354, 79–86 (2012).

Jiao, Y. et al. Clostridium difficile PSI polysaccharide: synthesis of the pentasaccharide repeating block, conjugation to exotoxin B subunit, and detection of natural anti-PSI IgG antibodies in horse serum. Carbohydr. Res. 378, 15–25 (2013).

Martin, C. E., Weishaupt, M. W. & Seeberger, P. H. Progress toward developing a carbohydrate-conjugate vaccine against Clostridium difficile ribotype 027: synthesis of the cell-surface polysaccharide PS-I repeating unit. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 47, 10260–10262 (2011).

Ponader, D., Wojcik, F., Beceren-Braun, F., Dernedde, J. & Hartmann, L. Sequence-defined glycopolymer segments presenting mannose: synthesis and lectin binding affinity. Biomacromolecules 13, 1845–1852 (2012).

Ponader, D. et al. Carbohydrate-lectin recognition of sequence-defined heteromultivalent glycooligomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 2008–2016 (2014).

Wojcik, F., O’Brien, A. G., Götze, S., Seeberger, P. H. & Hartmann, L. Synthesis of carbohydrate-functionalised sequence-defined oligo(amidoamine)s by photochemical thiol-ene coupling in a continuous flow reactor. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 3090–3098 (2013).

Pillai, S., Dermody, K. & Metcalf, B. Immunogenicity of genetically engineered glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins containing a T-cell epitope from diphtheria toxin. Infect. Immun. 63, 1535–1540.

Broecker, F., Anish, C. & Seeberger, P. H. Generation of monoclonal antibodies against defined oligosaccharide antigens. Methods Mol. Biol. 1331, 57–80 (2015).

Mayer, M. & James, T. L. NMR-based characterization of phenothiazines as a RNA binding scaffold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 4453–4460 (2004).

Altschuh, D. et al. Deciphering complex protein interaction kinetics using Interaction Map. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 428, 74–79 (2012).

Ladbury, J. E. Just add water! The effect of water on the specificity of protein-ligand binding sites and its potential application to drug design. Chem. Biol. 3, 973–980 (1996).

Kirschner, K. N. et al. GLYCAM06: a generizable biomolecular force field. Carbohydrates. J. Comput. Chem. 29, 622–655 (2008).

Zahnd, C. et al. Directed in vitro evolution and crystallographic analysis of a peptide-binding single chain antibody fragment (scFv) with low picomolar affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 18870–18877 (2004).

Zahnd, C., Sarkar, C. A. & Plückthun, A. Computational analysis of off-rate selection experiments to optimize affinity maturation by directed evolution. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 23, 175–184 (2010).

Batista, F. D. & Neuberger, M. S. Affinity dependence of the B cell response to antigen: a threshold, a ceiling, and the importance of off-rate. Immunity 8, 751–759 (1998).

Maynard, J. A. et al. Protection against anthrax toxin by recombinant antibody fragments correlates with antigen affinity. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 597–601 (2002).

Yang, W. P. et al. CDR walking mutagenesis for the affinity maturation of a potent human anti-HIV-1 antibody into the picomolar range. J. Mol. Biol. 254, 392–403 (1995).

Jackson, H. et al. Antigen specificity and tumour targeting efficiency of a human carcinoembryonic antigen-specific scFv and affinity-matured derivatives. Br. J. Cancer 78, 181–188 (1998).

Bernardi, A. et al. Multivalent glycoconjugates as anti-pathogenic agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 4709–4727 (2013).

Lo-Man, R. et al. A fully synthetic immunogen carrying a carcinoma-associated carbohydrate for active specific immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 59, 1520–1524 (1999).

Grigalevicius, S. et al. Chemoselective assembly and immunological evaluation of multiepitopic glycoconjugates bearing clustered Tn antigen as synthetic anticancer vaccines. Bioconjug. Chem. 16, 1149–1159 (2005).

Wu, X., Ling, C. C. & Bundle, D. R. A new homobifunctional p-nitro phenyl ester coupling reagent for the preparation of neoglycoproteins. Org. Lett. 6, 4407–4410 (2004).

Pozsgay, V. et al. Protein conjugates of synthetic saccharides elicit higher levels of serum IgG lipopolysaccharide antibodies in mice than do those of the O-specific polysaccharide from Shigella dysenteriae type 1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 5194–5197 (1999).

Cavallari, M. et al. A semisynthetic carbohydrate-lipid vaccine that protects against S. pneumoniae in mice. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 950–956 (2014).

Peters, T. A matter of order: how E-selectin makes sweet contacts. Chembiochem. 13, 2325–2326 (2012).

Bundle, D. R. & Young, N. M. Carbohydrate-protein interactions in antibodies and lectins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2, 666–673 (1992).

Brummell, D. A. et al. Probing the combining site of an anti-carbohydrate antibody by saturation-mutagenesis: role of the heavy-chain CDR3 residues. Biochemistry 32, 1180–1187 (1993).

Toone, E. J. Structure and energetics of protein-carbohydrate complexes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 4, 719–728 (1994).

Garcia-Hernandez, E., Zubillaga, R. A., Rojo-Dominguez, A., Rodriguez-Romero, A. & Hernandez-Arana, A. New insights into the molecular basis of lectin-carbohydrate interactions: a calorimetric and structural study of the association of hevein to oligomers of N-acetylglucosamine. Proteins 29, 467–477 (1997).

Garcia-Hernandez, E. & Hernandez-Arana, A. Structural bases of lectin-carbohydrate affinities: comparison with protein-folding energetics. Protein Sci. 8, 1075–1086 (1999).

Dam, T. K. & Brewer, C. F. Thermodynamic studies of lectin-carbohydrate interactions by isothermal titration calorimetry. Chem. Rev. 102, 387–429 (2002).

Sigurskjold, B. W., Altman, E. & Bundle, D. R. Sensitive titration microcalorimentric study of the binding of Salmonella O-antigenic oligosaccharides by a monoclonal antibody. Eur. J. Biochem. 197, 239–246 (1991).

Sigurskjold, B. W. & Bundle, D. R. Thermodynamics of oligosaccharide binding to a monoclonal antibody specific for a Salmonella O-antigen point to hydrophobic interactions in the binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 8371–8376 (1992).

Bundle, D. R. et al. Molecular recognition of a Salmonella trisaccharide epitope by monoclonal antibody Se155-4. Biochemistry 33, 5172–5182 (1994).

Evans, S. V. et al. Evidence for the extended helical nature of polysaccharide epitopes. The 2.8Å resolution structure and thermodynamics of ligand binding of an antigen binding fragment specific for alpha-(2→8)-polysialic acid. Biochemistry 34, 6737–6744 (1995).

Harris, S. L. et al. Exploring the basis of peptide-carbohydrate cross-reactivity: evidence for discrimination by peptides between closely related anti-carbohydrate antibodies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 2454–2459 (1997).

Muller-Loennies, R., Brade, L., MacKenzie, C. R., Di Padova, F. E. & Brade, H. Identification of a cross-reactive epitope widely present in lipopolysaccharide from enterobacteria and recognized by the cross-protective monoclonal antibody WN1 222-5. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25618–25627 (2003).

Pitner, J. B. et al. Bivalency and epitope specificity of a high-affinity IgG3 monoclonal antibody to the Streptococcus group A carbohydrate antigen. Molecular modeling of a Fv fragment. Carbohydr. Res. 324, 17–29 (2000).

Vyas, N. K. et al. Molecular recognition of oligosaccharide epitopes by a monoclonal Fab specific for Shigella flexneri Y lipopolysaccharide: X-ray structures and thermodynamics. Biochemistry 41, 13575–13585 (2002).

Müller-Loennies, S. et al. Characterization of high affinity monoclonal antibodies specific for chlamydial lipopolysaccharide. Glycobiology 10, 121–130 (2000).

Nguyen, H. P. et al. Germline antibody recognition of distinct carbohydrate epitopes. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 1019–1025 (2003).

Harris, S. L. & Fernsten, P. Thermodynamics and density of binding of a panel of antibodies to high-molecular-weight capsular polysaccharides. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16, 37–42 (2009).

Ardá, A. et al. Molecular recognition of complex-type biantennary N-glycans by protein receptors: a three-dimensional view on epitope selection by NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 2667–2675 (2013).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Krannig, K. S. & Schlaad, H. pH-responsive bioactive glycopolypeptides with enhanced helicity and solubility in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18542–18545 (2012).

Turula, V. E. Jr, Gore, T., Singh, S. & Arumugham, R. G. Automation of the anthrone assay for carbohydrate concentration determinations. Anal. Chem. 82, 1786–1792 (2010).

Oberli, M. A. et al. A possible oligosaccharide-conjugate vaccine candidate for Clostridium difficile is antigenic and immunogenic. Chem. Biol. 18, 580–588 (2011).

Hewitt, M. C. & Seeberger, P. H. Solution and solid-support synthesis of a potential leishmaniasis carbohydrate vaccine. J. Org. Chem. 66, 4233–4243 (2001).

Hewitt, M. C. & Seeberger, P. H. Automated solid-phase synthesis of a branched Leishmania cap tetrasaccharide. Org. Lett. 3, 3699–3702 (2001).

Anish, C. et al. Immunogenicity and diagnostic potential of synthetic antigenic cell surface glycans of Leishmania. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 2412–2422 (2013).

Case, D. A. et al. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1668–1688 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Max Planck Society, the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant number 0315447), the Körber Foundation (Körber Prize to P.H.S.) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB-TR84 C8 to P.H.S.). C.R. and L.H. are supported by the German Research Foundation through Emmy Noether fellowships (RA1944/2-1 and HA5950/1-1, respectively). J.H. thanks the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie for a stipend. We thank Dr Bernd Lepenies (MPI-CI) for advice and support on animal ethics, Professor Dr Markus Wahl (Freie Universität Berlin) for providing the ITC instrument and Nicole Holton (Freie Universität Berlin) for kind help with the ITC measurements. We thank Professor Dr Helmut Schlaad (MPI-CI) for access to the photochemical set-up. We appreciate the kind support of Drs Vanya Uzunova and Marco Marenchino (GE Healthcare) with SPR data analysis. IM analysis performed by Professor Dr Magnus Malmqvist and Professor Dr Karl Andersson (Ridgeview Diagnostics AB) is thankfully acknowledged. We are grateful to Dr Sharavathi Guddehalli Parameswarappa, Benjamin Schumann and Dr Claney Lebev Pereira of the MPI-CI for kind help with the protein conjugation reactions. Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with the UCSF Chimera package. Chimera is developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (supported by NIGMS P41-GM103311). We thank Pfénex, Inc. for providing CRM197 at a reduced price.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.H.S. and C.A. initiated this study. F.B. performed mouse immunizations and hybridoma development with assistance from A.W., glycan microarray, SPR and ITC experiments. J.H. and C.R. performed and analysed NMR experiments and modelling of 1. C.M. synthesized compounds 1–7 and 9. J.Y.B. synthesized compound 8. F.W. and L.H. designed and synthesized compounds 10 and 11. P.H.S., C.A. and F.B. wrote the manuscript with assistance from J.H., C.M., F.W., L.H. and C.R. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-15, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Notes 1-2 and Supplementary References (PDF 3279 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Broecker, F., Hanske, J., Martin, C. et al. Multivalent display of minimal Clostridium difficile glycan epitopes mimics antigenic properties of larger glycans. Nat Commun 7, 11224 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11224

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11224

This article is cited by

-

Synthesis of a glycan hairpin

Nature Chemistry (2023)

-

Straightforward synthesis of the hexasaccharide repeating unit of the O-specific polysaccharide of Salmonella arizonae O62

Glycoconjugate Journal (2023)

-

Comparison of polysaccharide glycoconjugates as candidate vaccines to combat Clostridiodes (Clostridium) difficile

Glycoconjugate Journal (2021)

-

Engineering orthogonal human O-linked glycoprotein biosynthesis in bacteria

Nature Chemical Biology (2020)

-

Deciphering minimal antigenic epitopes associated with Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei lipopolysaccharide O-antigens

Nature Communications (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.