Abstract

The development of a low-cost, high-performance platinum-group-metal-free hydroxide exchange membrane fuel cell is hindered by the lack of a hydrogen oxidation reaction catalyst at the anode. Here we report that a composite catalyst, nickel nanoparticles supported on nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes, has hydrogen oxidation activity similar to platinum-group metals in alkaline electrolyte. Although nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes are a very poor hydrogen oxidation catalyst, as a support, it increases the catalytic performance of nickel nanoparticles by a factor of 33 (mass activity) or 21 (exchange current density) relative to unsupported nickel nanoparticles. Density functional theory calculations indicate that the nitrogen-doped support stabilizes the nanoparticle against reconstruction, while nitrogen located at the edge of the nanoparticle tunes local adsorption sites by affecting the d-orbitals of nickel. Owing to its high activity and low cost, our catalyst shows significant potential for use in low-cost, high-performance fuel cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The hydrogen economy provides an efficient and environmentally friendly pathway to store and consume energy1,2. Fuel cells, especially the recently developed polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells, are considered as the most promising device to convert the chemical energy of hydrogen to electricity3. The hydrogen fuel cells are based on two half-cell reactions: hydrogen oxidation reaction (HOR) at the anode and oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) at the cathode. To date, Pt is the most active catalyst for both HOR and ORR4. However, the commercialization of fuel cells is hindered by the high price of Pt (∼$50 g−1). Although the total content of platinum-group metals (PGMs) in the state-of-the-art proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) stacks has decreased significantly in the past decades, more than 0.137 gPt kW−1 is still needed5. One promising approach to reduce the cost of fuel cells is to switch the operating environment from an acidic to a basic one (that is, a hydroxide exchange membrane fuel cell, HEMFC), thus opening up the possibility of using PGM-free catalysts and other cheaper components6. For the cathode of the HEMFC, some PGM-free and metal-free ORR catalysts have been developed that show comparable activity to Pt in alkaline media7,8,9,10. However, for the anode side, only a few PGMs (for example, Pt, Ir and Pd) show adequate activity11,12. The HOR catalysed by Pt is very fast in acidic conditions so that a very low loading of the Pt catalyst could be used relative to the cathode side in PEMFCs. However, the HOR activities of PGMs are ∼100 times slower in alkaline solutions11,13. As a result, a much higher loading of the HOR catalyst is required (0.4 mgPt cm−2 in a HEMFC compared with 0.03 mgPt cm−2 in a PEMFC) to achieve similar performance5,14. Thus, it is highly desirable to develop PGM-free anode catalysts for the HOR in alkaline electrolyte.

Unlike its reverse reaction (hydrogen evolution reaction, HER)15,16,17, only a few PGM-free HOR catalysts have been reported. One possibility is to use Raney Ni as the HOR catalyst in liquid alkaline fuel cells18,19,20. However, it is functional only under very high alkalinity (6 M KOH) while the activity remains low. It is not catalytically active for a HEMFC, which can be mimicked as 0.1–1 M KOH21. Efforts have been made to improve the HOR activity of the Ni-based catalyst in the last decade. Ni alloys, such as NiMo and NiTi, have been shown to enhance the HOR activity20. Our recent work has also shown that electrochemically deposited NiCoMo on an Au substrate has a high HOR activity22. Zhuang and co-workers decorated Ni particles with CrOx to weaken the Ni–O bond and stabilize the Ni catalysts. A HEMFC incorporating this PGM-free catalyst has been fabricated, and it exhibits a peak power density of 50 mW cm−2 (ref. 21) Although the power density is still low (compared with the peak power density of more than 1,000 mW cm−2 for PEMFCs), it demonstrates the possibility to fabricate low-cost PGM-free fuel cells. However, their activities are still incomparable with PGM-based catalysts.

In the current study, we synthesize Ni nanoparticles supported on N-doped carbon nanotubes (Ni/N-CNT) by a wet chemical method, and the Ni/N-CNT shows a high HOR catalytic activity in 0.1 M KOH solution. N-CNTs are not only the support for the Ni nanoparticles, but also a promoter for the catalytic activity. Owing to its special electronic properties, the N-doped carbon structure has been employed to enhance the catalytic activity of the methanol oxidation reaction and the ORR23. We use N-CNT as a support for the HOR catalyst and demonstrate that, relative to Ni nanoparticles, the mass activity and exchange current density of Ni/N-CNT increases by a factor of 33 and 21, respectively. To understand the interaction between the Ni nanoparticle and the N-CNT support, density functional theory (DFT) calculations are undertaken. The DFT calculations indicate that, when nitrogen dopants are present at the edge of the nanoparticle, the Ni nanoparticle is stabilized on the support and locally activated for the HOR because of modulation of the Ni d-orbitals. Using the volcano relationship between the HOR activity and the hydrogen adsorption energy, predicted first-principles exchange current densities of the model systems are in good agreement with the measured exchange current densities of the experimental catalysts. Owing to its high activity and low cost, Ni/N-CNT has great potential to be used as the anode in HEMFCs, thereby finally bringing to fruition a high-performance and low-cost PGM-free HEMFC.

Results

Catalyst synthesis and characterization

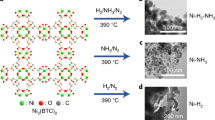

A two-step approach was developed to synthesize the Ni/N-CNT hybrid catalysts. First, Ni was selectively grown on mildly oxidized multiwalled CNTs by reducing nickel salt in an aqueous solution. Second, ammonia and hydrazine were added and then subjected to a hydrothermal treatment at 150 °C. This step led to better crystallization of the Ni nanoparticles, partial reduction of the oxidized CNTs and, more importantly, doping of nitrogen into the CNTs.

The scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Fig. 1a) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Fig. 1b) images clearly show that the nanoparticles with an average size of 20 nm are selectively grown on the surface of the CNT. The diffraction rings in the selected area electron diffraction (inset of Fig. 1b) pattern can be either indexed to Ni or CNT. The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, Supplementary Fig. 1) also indicated the presence of the Ni component. The enlarged TEM image (Fig. 1c) shows that all the nanoparticles are directly supported on the CNT. Moreover, the high-resolution TEM (HRTEM, Fig. 1d) image clearly indicates the layered structure of the CNT wall, with an interplanar spacing of 0.35 nm, which is similar to the (002) plane of graphite. The lattice fringe of the nanoparticle has an interplanar spacing of 0.21 nm and is ascribed to the (111) plane of Ni.

The X-ray diffraction pattern (Fig. 2a) further confirms the mixed Ni and CNT composition of the catalyst. The loading of Ni on carbon was calculated as ∼70 wt % by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, method shown in Supplementary Fig. 2). The N doping was examined with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Fig. 2b). A peak at ca. 400 eV clearly exists in the high-resolution N 1s XPS spectrum (inset of Fig. 2b), confirming the N doping. It can be deconvoluted into two peaks, 399.0 and 400.3 eV, corresponding to pyridinic N and pyrrolic N in doped CNT, respectively24,25. The N-doping amount to carbon was calculated from the XPS spectrum as 2.4 at %.

Electrochemical HOR performance

The electrocatalytic activity for the HOR was investigated by rotating disk electrode measurements using a standard three-electrode system in 0.1 M KOH. The catalyst was uniformly cast on a 5-mm glassy carbon electrode with a Ni loading of 0.25 mgNi cm−2. Undoped CNT supported Ni nanoparticles (represented as Ni/CNT) and unsupported Ni nanoparticles (represented as Ni) catalysts (corresponding TEM images and X-ray diffraction patterns are shown in Supplementary Figs 3 and 4, respectively) with the same loading were also studied for comparison.

Figure 3a shows the polarization curve of the catalysts in H2-saturated electrolyte. The anodic current above 0 V (versus the reversible hydrogen electrode, same hereafter) is assigned to the oxidation of H2. The catalytic activity for HOR on the three Ni-based catalysts follows the sequence of Ni/N-CNT>Ni/CNT>Ni. The current density of Ni/N-CNT is much higher than either Ni/CNT or Ni and shows an onset potential as low as 0 V. The bare N-CNT shows almost no catalytic activity for HOR, indicating that the enhanced catalytic activity for Ni/N-CNT comes from the synergetic effect of the combined structure. The Ni/N-CNT catalyst was also tested in an Ar-saturated electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 5) and showed no anodic current, confirming the catalytic reaction of HOR.

(a) Polarization curves of Ni/N-CNT, Ni/CNT, Ni (all of the three catalysts with a loading of 0.25 mgNi cm−2) and N-CNT (0.1 mgC cm−2) catalysts in H2-saturated 0.1 M KOH at a scan rate of 1 mV s−1 and rotating speed of 2,500 r.p.m. (b) Polarization curves of Ni/N-CNT in H2-saturated 0.1 M KOH at a scan rate of 1 mV s−1 and various rotating speeds. Inset is the Koutecky–Levich plot at an overpotential of 50 mV. (c) HOR/HER Tafel plots of the specific current density on Ni/N-CNT, Ni/CNT and Ni in H2-saturated 0.1 M KOH. The dashed lines indicate the Butler–Volmer fitting. (d) Mass activity at 50 mV (unpatterned) and exchange current density (patterned) of the Ni/N-CNT, Ni/CNT and Ni, respectively.

The polarization curves at different rotating speeds have also been studied (Fig. 3b). The current density increases with increasing rotating speed owing to improved mass transport. The overall current density is under mixed kinetic-diffusion control. The diffusion-limited current density (jd) for a rotating disk electrode is described by the Levich equation as a function of rotating speed (ω):

where B is the Levich constant, c0 is the solubility of H2 in 0.1 M KOH26. The Levich constant is a function of the diffusivity of H2 (D), number of the electrons (n) transferred in the HOR and kinematic viscosity of the electrolyte (ν). The overall current density (j) can be deconvoluted into kinetic (jk) and diffusional (jd) components following the Koutecky–Levich equation:

A linear relationship between the inverse of j at 50 mV and ω1/2 is observed in the Koutecky–Levich plots (inset of Fig. 3b). The calculated slope is 5.21 cm2 mA−1 s−1/2, which is reasonably close to the theoretical number (4.87 cm2 mA−1 s−1/2, for the two-electron transfer of HOR)13. The intercept of the extrapolated line corresponds to the inverse of the purely kinetic current density, and the jk for Ni/N-CNT is 2.33 mA cmdisk−2 at 50 mV overpotential. Normalizing by the metal loading of the catalyst, the mass activity of the Ni/N-CNT is 9.3 mA mgNi−1 at 50 mV overpotential, shown in Fig. 3d and Supplementary Table 1 along with that of Ni/CNT and Ni. The mass activity of our synthesized unsupported Ni nanoparticles (0.28 mA mgNi−1) is comparable to the activities of Raney Ni reported in the literature27,28,29,30,31,32. By contrast, the mass activity of the Ni/N-CNT is 33 times as high as the pure Ni nanoparticle, making Ni/N-CNT one of the most active PGM-free catalysts for HOR (Supplementary Table 2 lists the HOR mass activity of the PGM-free catalyst reported in the literature).

To understand the intrinsic activity of the Ni/N-CNT catalyst, we normalized the current by the electrochemical surface area (ECSA). The ECSAs of each Ni-based catalyst were measured in Ar-saturated 0.1 M KOH using a cyclic voltammetry method and were calculated from the OH desorption region of Ni subtracted by HER current using a charge density of 514 μC cmNi−2 for one monolayer of OH adsorption on Ni (Supplementary Fig. 6)33,34. Figure 3c shows the ECSA-normalized kinetic currents as a function of the overpotential. The HOR kinetic current was obtained from the Koutecky–Levich equation (equation 2). The exchange current density (j0, shown in Fig. 3d and Supplementary Table 1) was obtained by fitting the ECSA-normalized HOR/HER kinetic current density to the Bulter–Volmer equation:

Here α is the charge transfer coefficient, F is Faraday’s constant, R is the universal gas constant, T is the temperature and η is the overpotential13. All the curves can be fitted with a value of α in the range of 0.4∼0.5, indicating a good symmetry for the HOR and HER branches. The j0 values obtained from linear fitting of micropolarization regions (−10–10 mV, see Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 1) are consistent with the values of j0 obtained from Bulter–Volmer fitting. The Ni/N-CNT has an exchange current density of 0.028 mA cmNi−2, which is three times higher than Ni/CNT and 21 times higher than Ni. The exchange current density for Ni/N-CNT is among the best PGM-free HOR catalysts and is comparable to some PGM catalysts, such as Pd (Supplementary Table 3)11,35. Although the HOR activity of the Ni/N-CNT is still over one order of magnitude less than the state-of-the-art Pt catalyst, the ultralow price of Ni makes it promising for commercial applications.

Theoretical investigation

On the basis of a Wulff construction, fcc metals, such as Ni, are known to prefer a cuboctahedral geometry, exposing the {111} and {100} facets36. To model the nanoparticle, a 13-atom Ni nanocluster (Ni13) was chosen, as this was the smallest of the cuboctahedral ‘magic numbers’ (a larger nanoparticle, Ni37, was also studied and is discussed below)37. Because of the relatively large size of both the Ni nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes used experimentally, previous studies suggest that the curvature of the CNT support has a minimal effect38; as such, the CNT support is approximated with a graphene sheet to reduce the complexity of the model. This results in a Ni13 nanoparticle being deposited on both graphene (Ni/graphene) and nitrogen-doped graphene (Ni/N-graphene), with both the Ni13 nanoparticle and the support being allowed to relax. We have investigated the effect of the location of the nitrogen dopant relative to the nanoparticle by considering nitrogen at the centre (Nc) and nitrogen at the edge (Ne), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

In alkaline solutions, the HOR follows either the Tafel–Volmer or the Heyrovsky–Volmer mechanism. The possible elementary steps comprising the HOR are shown in Equations 4, 5, 6.

The key intermediate is the adsorbed hydrogen (Had) on the catalyst surface, which leads to the existence of a Sabatier volcano relationship with the hydrogen-binding energy of the catalyst as the descriptor39. Although mechanistically the Had written in the elementary steps above is likely the overpotential deposited hydrogen (HOPD), the HOR/HER activity seems to correlate well to the electrochemical adsorption energy of the underpotential deposited hydrogen (HUPD), which is shown to be similar to the chemical adsorption energy of hydrogen40,41,42. In this study we calculate chemical adsorption energy of hydrogen on Ni13 nanoclusters.

The volcano relationship involving adsorbed hydrogen has been well established in acidic solutions43. While some debate remains on the adequacy of using the hydrogen-binding energy as a descriptor in alkaline media, there is significant evidence that the hydrogen-binding energy remains the key descriptor of activity12,44,45. This allows for the implementation of a hybrid data-driven/first-principles model to evaluate the efficacy of different catalysts and to estimate activity compared with single metals. This hybrid approach was employed successfully in propane total oxidation46. Details of the construction of the hybrid activity model are given in the Supplementary Methods.

The heterogeneity of the hydrogen-binding sites in the supported Ni nanocluster model system results in a distribution of binding energies shown in Fig. 4a. Here we see a large amount of variability among the metal-support systems at high binding energies, with an unsupported Ni13 nanocluster and Ni/graphene having a large number of sites that adsorb hydrogen too strongly to be active for HOR. On the other hand, Fig. 4a shows that a Ni nanoparticle supported on Ne-graphene does not possess large binding energies as in the unsupported Ni and the Ni/graphene systems.

(a) Distribution of site-dependent hydrogen-binding energies for each model system. (b) Distribution of relaxation energies for each model system on hydrogen-binding to each site. The ends of the dashed line represent the minimum and maximum values of Erelax for each model structure. These ranges collectively represent the distribution of Erelax values for each hydrogen adsorption site on the Ni13 cluster. The bottom of the box represents the first quartile (that is, splits the lowest 25% of relaxation energies from the highest 75%) and the top of the box represents the third quartile (that is, splits the highest 25% of relaxation energies from the lowest 75%). Bold horizontal band is the median value. (c) Shifts in the d-band centre with respect to the Fermi level and binding energy at adjacent Ni sites (1,2,3) and (2,3,4) for Ni/graphene, Ni/Nc-graphene and Ni/Ne-graphene. Inset is graphical depiction of the sites (Ni/Ne-graphene as an example). The (1,2,3) site represents the hollow site in coordination with the #1, #2 and #3 Ni atoms. The (2,3,4) site represents the hollow site in coordination with the #2, #3 and #4 Ni atoms. Blue, grey and red spheres represent Ni, C and N atoms, respectively.

The differences in the binding energies between the unsupported Ni13 nanocluster and the supported Ni13 arise from either an electronic (that is, charge transfer) or a geometric (that is, relaxation) origin47. For the strong binding sites, the nanocluster undergoes reconstruction as shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. The relative contributions of the electronic and the geometric support effects are decoupled by considering a nanocluster which is treated as rigid during hydrogen binding. For a rigid nanocluster, any differences in the binding energies result from the differences in the electronic structure of the Ni13 nanocluster because of the support. We define a relaxation energy, Erelax, as

where ΔEHrig is the hydrogen-binding energy on the rigid nanocluster, and ΔEHrel is the hydrogen-binding energy on the relaxed nanocluster. Here a larger Erelax implies a larger degree of Ni reconstruction. Figure 4b shows Erelax for all Ni-binding sites for the systems considered. The unsupported nanocluster is the least stable during hydrogen binding. With the exception of a fraction of binding sites, the nitrogen-doped supports exhibit better stabilization of the Ni nanocluster. In agreement with its lack of strongly binding sites (cf. Fig. 4a), Ni/Ne-graphene exhibits local relaxation with minimal reconstruction. In addition, when considering the rigid nanocluster, the difference in the average hydrogen-binding energy of Ni/Nc-graphene and Ni/Ne-graphene is less than 0.01 eV (versus 0.09 eV difference for the relaxed nanocluster). Thus, we observe that the rigid nanocluster’s binding characteristics are not greatly affected by the support (Nc-graphene or Ne-graphene).

Next, we examine what fundamental electronic properties of the Ni13 nanocluster are being affected by the support. A commonly employed electronic descriptor for the binding energies on metal surfaces is the energy of the d-band centre, ɛd, relative to the Fermi level, ɛF (ref. 48). The d-band centre describes the relative filling of the hybridized (d–s) and antibonding (d–s)* states of the Ni–H system. For an adsorbate, such as atomic hydrogen with a low-lying electronic state, the stabilization of the bonding states between the metal d-states and the hydrogen s-states decreases when the d-band of the metal is shifted up in energy (ɛd–ɛF is more positive) because of the energy mismatch between the metal d-band and the hydrogen s-state. As a result, the resulting antibonding part of the band is pushed up just above the Fermi level, which leads to stronger binding between the metal atoms and the adsorbate. In Fig. 4c, we see an upshift in the d-band centre of adjacent Ni-binding sites when an edge nitrogen atom is present. Owing to these sites originally lying in the weak binding region of Fig. 4a, the upshift in the d-band centre consequently activates these sites adjacent to Ne for the HOR by strengthening the binding energy by 0.1 eV. XPS valence band spectra, which are related to the d-band centres, were also studied (Supplementary Fig. 10)49. Thus, while the geometric effect of the support is responsible for the decrease in strong binding sites, edge nitrogen further tunes local binding sites by modulating the electronic properties of Ni.

Using the hybrid activity model for the HOR, we can now predict the intrinsic exchange current density of each of the model systems that were investigated (Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Note 1). In agreement with experimental measurements, Fig. 5 shows that an order of magnitude increase in the exchange current density is predicted for a graphene-supported nanocluster compared with an unsupported Ni catalyst. Additional improvement occurs when doping the graphene support with nitrogen, where having nitrogen at the edge of nanocluster (that is, directly interacting with surface Ni atoms) appears to be more effective than having nitrogen at the centre of the nanoparticle. Relating this discovery to the current experimental procedure, it is expected that edge nitrogen is predominant in the experimental material. This is because nitrogen doping is performed after the Ni nanoparticle was grown from the CNT surface. Thus, it is expected that only sites at the edge of the nanoparticle are available for nitrogen doping, and that lattice diffusion is the only mechanism by which nitrogen could be transported to the centre of the nanoparticle.

Unpatterned bars are the calculated exchange current densities and patterned bars are the measured values. The calculated exchange current density of Ni/Ne-graphene is shown for Ni/N-graphene. Error bars are 75% confidence intervals resulting from the regression of the volcano relationship in Supplementary Equation 2.

To confirm that the Ni13 is sufficiently large to capture the metal-support interaction of the experimental system, we performed calculations on a larger Ni37 nanoparticle (Supplementary Note 2). The d-orbitals of the Ni13 cluster correspond well to the larger Ni37 model (Supplementary Fig. 12). The difference in the calculated d-band centre is only 0.01 eV for the two nanoparticles, which indicates that the Ni13 is a good approximation for larger nanoparticles both in terms of its adsorption and electronic properties. The electronic effect of the N-dopant was found localized to the adsorption sites of the nearby Ni atoms (Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Table 4). Our findings suggest that even higher HOR activity could be obtained by making smaller Ni nanoparticles because of a larger fraction of adsorption sites that could be affected electronically by the N-dopant.

In summary, Ni/N-CNT as a highly active PGM-free HOR catalyst in alkaline condition was reported in this paper. The promoted HOR activity is attributed to the synergetic effect of the edge N atom in the CNT and Ni. The theoretical investigation indicated that the Ni nanoparticle has more sites with an optimal hydrogen-binding energy because of both a geometric and electronic interaction with the edge N atoms. Relative to Ni nanoparticles, the mass activity and exchange current density of Ni/N-CNT increases by a factor of 33 and 21, respectively. These results show that Ni/N-CNT is promising to be applied as the anode catalyst for HEMFCs.

Methods

Synthesis of nickel-based composite catalyst

In a typical synthesis of Ni/N-CNT, mildly oxidized MWCNTs (25 mg, 10–20 nm in diameter, Shenzhen Nanotech Port Co. Ltd., mildly oxidized through the modified Hummers method50) were dispersed in deionized water (10 ml) assisted by sonication for 30 min. After that, NiSO4·6H2O (0.262 g, 1 mmol) was added to the MWCNT suspension and sonicated for another 30 min. The suspension was transferred to a flask placed in an ice-water bath. Then ice-cold NaBH4 aqueous solution (1 wt %, 10 ml, ∼2.5 mmol) was added dropwise. After reaction at 0 °C for 2 h, the suspension was transferred to a 45-ml Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave. Ammonium hydroxide solution (28–30% NH3 basis, 5 ml) and hydrazine hydrate solution (78–82%, 2 ml) were added, and then the autoclave was sealed and subjected to a hydrothermal treatment at 150 °C for 4 h. The final product was collected by centrifugation at 8,000 r.p.m. for 10 min, washed with water and then redispersed in water (10 ml).

Ni and Ni/CNT were synthesized by similar procedures. Ni was synthesized without adding oxidized MWCNT and the pH was adjusted to 12 by ammonium hydroxide before the hydrothermal treatment. Ni/CNT was synthesized without adding ammonium hydroxide and hydrazine.

Physical characterization

The SEM was performed on a JEOL JSM-7400F SEM working at an acceleration voltage of 3 kV. The TEM, HRTEM and EDS were performed on a JEOL JEM-3010 TEM operating at 300 kV equipped with EDS system. The X-ray diffraction patterns were collected on a Bruker D8 Discovery diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ=0.15418, nm) operating at 40 kV and 40 mA. The TGA was performed on a Mettler Toledo TGA/DSA 1 STARe System under air flow (60 ml min−1) with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1. The XPS spectra were recorded on Thermo Fisher ESCALAB 250Xi XPS system with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source. The survey scans were conducted at a pass energy of 100 eV using a step size of 1 eV, and the high-revolution scans were conducted at a pass energy of 50 eV using a step size of 0.05 eV.

Electrochemical tests

The electrodes were prepared by casting catalyst inks on glassy carbon electrodes (5 mm in diameter, Pine Instruments, polished to a mirror-finishing with 0.05 μm alumina). The catalyst inks were prepared by dispersing catalyst in water with 0.05 wt % Nafion at a concentration of 2.5 mgNi ml−1. The catalyst ink (20 μl) was deposited on a glassy carbon electrode and dried in vacuum at room temperature, resulted in a metal loading of 0.25 mgNi cm−2. Electrochemical studies were carried out in a standard three-electrode system controlled with a multichannel potentiostat (Princeton Applied Research). As-prepared thin film electrode, which served as the working electrode, was mounted on a rotator and was immersed into 0.1 M KOH solution. An Ag/AgCl electrode with double junctions was used as the reference electrode. A Pt wire was used as the counterelectrode, which has an outer glass tube with a ceramic fritz to prevent the contamination of Pt. All potentials reported in this paper are referenced to the reversible hydrogen electrode potential. All the polarization curves were corrected for solution resistance, which was measured using AC-impedance spectroscopy from 200 kHz to 100 mHz and a voltage perturbation of 10 mV.

Computational methodology

Periodic DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio software package (VASP, version 5.3.2)51. The optPBE-vdW exchange-correlation functional52 was selected because of its qualitatively accurate representation of the potential energy surface of a Ni monolayer and graphene system53. The core electrons were represented with the projector-augmented wavefunction (PAW) method54,55, and a plane-wave cutoff of 400 eV was used for the valence electrons. The Methfessel–Paxton method of electron smearing was used with a smearing width of 0.1 eV (ref. 56). All geometry optimizations were performed using the conjugate gradient algorithm57 as implemented in VASP. The forces and energies were converged to 0.05 eV Å−1 and 10−4 eV, respectively. All calculations were spin-polarized because of the magnetic moment of Ni. For the Ni nanocluster systems, all calculations were performed at the Γ-point. A 5 × 5 graphene unit cell was used as the support. In the z direction, a vacuum layer of 15 Å was included. This unit cell was chosen to minimize interaction of the Ni13 nanocluster with its periodic image while still being computationally tractable. For the single metal surfaces used to establish the hybrid activity model, a 4 × 4 unit cell was used with a 3 × 3 × 1 Monkhorst–Pack k-point sampling of the Brillouin zone58.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Zhuang, Z. et al. Nickel supported on nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes as hydrogen oxidation reaction catalyst in alkaline electrolyte. Nat. Commun. 7:10141 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10141 (2016).

References

Bockris, J. O. M. Hydrogen economy in the future. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 24, 1–15 (1999).

Bockris, J. O. M. The hydrogen economy: its history. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 38, 2579–2588 (2013).

Gasteiger, H. A. & Markovic, N. M. Just a dream-or future reality? Science 324, 48–49 (2009).

Gasteiger, H. A., Kocha, S. S., Sompalli, B. & Wagner, F. T. Activity benchmarks and requirements for Pt, Pt-alloy, and non-Pt oxygen reduction catalysts for PEMFCs. Appl. Catal. B 56, 9–35 (2005).

Steinbach, A. DOE Hydrogen and Fuel Cells Pro gram 2015 Annual Progress Report. Report no. FC104 (US Department of Energy, Washington, DC, USA, 2015).

Varcoe, J. R. & Slade, R. C. T. Prospects for alkaline anion-exchange membranes in low temperature fuel cells. Fuel Cells 5, 187–200 (2005).

Chung, H. T., Won, J. H. & Zelenay, P. Active and stable carbon nanotube/nanoparticle composite electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction. Nat. Commun. 4, 1922 (2013).

Wu, G. & Zelenay, P. Nanostructured Nonprecious Metal Catalysts for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 1878–1889 (2013).

Piana, M. et al. H-2/air alkaline membrane fuel cell performance and durability, using novel ionomer and non-platinum group metal cathode catalyst. J. Power Sources 195, 5875–5881 (2010).

Sa, Y. J. et al. Carbon nanotubes/heteroatom-doped carbon core-sheath nanostructures as highly active, metal-free oxygen reduction electrocatalysts for alkaline fuel cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 4102–4106 (2014).

Durst, J. et al. New insights into the electrochemical hydrogen oxidation and evolution reaction mechanism. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 2255–2260 (2014).

Strmcnik, D. et al. Improving the hydrogen oxidation reaction rate by promotion of hydroxyl adsorption. Nat. Chem. 5, 300–306 (2013).

Sheng, W., Gasteiger, H. A. & Shao-Horn, Y. Hydrogen oxidation and evolution reaction kinetics on platinum: acid vs alkaline electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, B1529–B1536 (2010).

Wang, Y. et al. Pt-Ru catalyzed hydrogen oxidation in alkaline media: oxophilic effect or electronic effect? Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 177–181 (2015).

Nocera, D. G. The artificial leaf. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 767–776 (2012).

Gong, M. et al. Nanoscale nickel oxide/nickel heterostructures for active hydrogen evolution electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 5, 4695 (2014).

McCrory, C. C. L. et al. Benchmarking hydrogen evolving reaction and oxygen evolving reaction electrocatalysts for solar water splitting devices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4347–4357 (2015).

Kenjo, T. Chromium-doped Raney-nickel catalyst for hydrogen electrodes in alkaline fuel-cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 132, 383–386 (1985).

Kiros, Y. & Schwartz, S. Long-term hydrogen oxidation catalysts in alkaline fuel cells. J. Power Sources 87, 101–105 (2000).

Mund, K., Richter, G. & Sturm, F. V. Titanium-containing Raney-nickel catalyst for hydrogen electrodes in alkaline fuel-cell systems. J. Electrochem. Soc. 124, 1–6 (1977).

Lu, S., Pan, J., Huang, A., Zhuang, L. & Lu, J. Alkaline polymer electrolyte fuel cells completely free from noble metal catalysts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 20611–20614 (2008).

Sheng, W. et al. Non-precious metal electrocatalysts with high activity for hydrogen oxidation reaction in alkaline electrolytes. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 1719–1724 (2014).

Wood, K. N., O'Hayre, R. & Pylypenko, S. Recent progress on nitrogen/carbon structures designed for use in energy and sustainability applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 1212–1249 (2014).

Yang, Z. X., Xia, Y. D. & Mokaya, R. Aligned N-doped carbon nanotube bundles prepared via CVD using zeolite substrates. Chem. Mater. 17, 4502–4508 (2005).

Wang, H., Maiyalagan, T. & Wang, X. Review on recent progress in nitrogen-doped graphene: synthesis, characterization, and its potential applications. ACS Catal. 2, 781–794 (2012).

Markovic, N. M., Sarraf, S. T., Gasteiger, H. A. & Ross, P. N. Hydrogen electrochemistry on platinum low-index single-crystal surfaces in alkaline solution. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 92, 3719–3725 (1996).

Ewe, H., Justi, E. & Schmitt, A. Structure and properties of Raney-nickel catalysts with alloying for alkaline fuel-cells. Electrochim. Acta 19, 799–808 (1974).

Ewe, H., Justi, E. & Schmitt, A. Studies of preservation of Raney-nickel-mixed catalysts. Energy Convers. 14, 35–41 (1975).

Jenseit, W., Khalil, A. & Wendt, H. Meterial properties and processing in the production of fuel-cell components. 1. Hydrogen anodes from Raney-nickel for lighweight alkaline fuel-cells. J. Appl. Electrochem. 20, 893–900 (1990).

AlSaleh, M. A., Gultekin, S., AlZakri, A. S. & Khan, A. A. A. Steady state performance of copper impregnated Ni/PTFE gas diffusion electrode in alkaline fuel cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 21, 657–661 (1996).

SleemUrRahman, M. A., AlSaleh, M. A., AlZakri, A. S. & Gultekin, S. Preparation of Raney-Ni gas diffusion electrode by filtration method for alkaline fuel cells. J. Appl. Electrochem. 27, 215–220 (1997).

Al-Saleh, M. A., Sleem, Ur, R., Kareemuddin, S. & Al-Zakri, A. S. Novel methods of stabilization of Raney-Nickel catalyst for fuel-cell electrodes. J. Power Sources 72, 159–164 (1998).

Machado, S. A. S. & Avaca, L. A. The hydrogen evolution reaction on nickel surfaces stabilized by H-absorption. Electrochim. Acta 39, 1385–1391 (1994).

Grden, M., Alsabet, M. & Jerkiewicz, G. Surface science and electrochemical analysis of nickel foams. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4, 3012–3021 (2012).

Henning, S., Herranz, J. & Gasteiger, H. A. Bulk-palladium and palladium-on-gold electrocatalysts for the oxidation of hydrogen in alkaline electrolyte. J. Electrochem. Soc. 162, F178–F189 (2015).

Wulff, G. On the question of speed of growth and dissolution of crystal surfaces. Z. Krystallogr. Mineral. 34, 449–530 (1901).

Miehle, W., Kandler, O., Leisner, T. & Echt, O. Mass-spectrometric evidence for icosahedral structrue in large rare-gas clusters -Ar, Kr, Xe. J. Chem. Phys. 91, 5940–5952 (1989).

Popov, V. N. Curvature effects on the structural, electronic and optical properties of isolated single-walled carbon nanotubes within a symmetry-adapted non-orthogonal tight-binding model. New J. Phys. 6, 17 (2004).

Trasatti, S. Work Function, electronegativity, and electrochemical behavior of metals. 3. Electrolytic hydrogen evolution in acid solutions. J. Electroanal. Chem. 39, 163–184 (1972).

Jerkiewicz, G. & Zolfaghari, A. Determination of the energy of the metal−underpotential-deposited hydrogen bond for rhodium electrodes. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 8454–8461 (1996).

Jerkiewicz, G. Hydrogen sorption AT/IN electrodes. Prog. Surf. Sci. 57, 95–186 (1998).

Conway, B. E. & Tilak, B. V. Interfacial processes involving electrocatalytic evolution and oxidation of H-2, and the role of chemisorbed H. Electrochim. Acta 47, 3571–3594 (2002).

Norskov, J. K. et al. Trends in the exchange current for hydrogen evolution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 152, J23–J26 (2005).

Sheng, W., Myint, M., Chen, J. G. & Yan, Y. Correlating the hydrogen evolution reaction activity in alkaline electrolytes with the hydrogen binding energy on monometallic surfaces. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 1509–1512 (2013).

Sheng, W. et al. Correlating hydrogen oxidation and evolution activity on platinum at different pH with measured hydrogen binding energy. Nat. Commun. 6, 5848 (2015).

Peela, N. R., Zheng, W., Lee, I. C., Karim, A. M. & Vlachos, D. G. Core-shell nanocatalyst design by combining high-throughput experiments and first-principles simulations. Chemcatchem 5, 3712–3718 (2013).

Jenness, G. R. & Schmidt, J. R. Unraveling the role of metal-support interactions in heterogeneous catalysis: oxygenate selectivity in fischer-tropsch synthesis. ACS Catal. 3, 2881–2890 (2013).

Hammer, B. & Norskov, J.K. in Advances in Catalysis, Vol. 45 eds Gates B. C., Knozinger H. 71–129Elsevier (2000).

Gorzkowski, M. T. & Lewera, A. Probing the limits of d-band center theory: electronic and electrocatalytic properties of Pd-shell-Pt-core nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 18389–18395 (2015).

Liang, Y. et al. Oxygen reduction electrocatalyst based on strongly coupled cobalt oxide nanocrystals and carbon nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 15849–15857 (2012).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Klimes, J., Bowler, D. R. & Michaelides, A. Chemical accuracy for the van der Waals density functional. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 22, 022201 (2010).

Wellendorff, J. et al. Density functionals for surface science: exchange-correlation model development with Bayesian error estimation. Phys. Rev. B 85, 235149 (2012).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Methfessel, M. & Paxton, A. T. High-precision sampling for Brillouin-zone intergration in metals. Phys. Rev. B 40, 3616–3621 (1989).

Teter, M. P., Payne, M. C. & Allan, D. C. Solution of Schrodinger-equation for large systems. Phys. Rev. B 40, 12255–12263 (1989).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-Zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Acknowledgements

The experimental work was partially supported by the ARPA-E programme of the US Department of Energy under the Award Number DE-AR0000009. The computational work was financially supported from the Catalysis Center for Energy Innovation, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Award Number DE-SC0001004. S.A.G. acknowledges a UDEI fellowship. This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported by the Office of Science of the US Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02–05CH11231.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. and Y.Y. conceived the idea. Z.Z. performed the catalyst synthesis, characterization and electrochemical test. J.Z. performed SEM observations. S.A.G., G.R.J., S.C. and D.G.V. performed the DFT calculations and analysed the computational data. Z.Z., S.A.G., D.G.V. and Y.Y. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-13, Supplementary Tables 1-4, Supplementary Notes 1-2, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 1105 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhuang, Z., Giles, S., Zheng, J. et al. Nickel supported on nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes as hydrogen oxidation reaction catalyst in alkaline electrolyte. Nat Commun 7, 10141 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10141

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10141

This article is cited by

-

Metal-support interaction boosts the stability of Ni-based electrocatalysts for alkaline hydrogen oxidation

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Tuning the apparent hydrogen binding energy to achieve high-performance Ni-based hydrogen oxidation reaction catalyst

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Progress and prospect of Pt-based catalysts for electrocatalytic hydrogen oxidation reactions

Nano Research (2024)

-

Antimony oxides-protected ultrathin Ir-Sb nanowires as bifunctional hydrogen electrocatalysts

Nano Research (2024)

-

Towards reliable assessment of hydrogen oxidation electrocatalysts for anion-exchange membrane fuel cells

Nano Research (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.