Abstract

Transition metals can catalyse the stereoselective synthesis of cyclic organic molecules in a highly atom-efficient process called cycloisomerization. Many diastereoselective (substrate stereocontrol), and enantioselective (catalyst stereocontrol) cycloisomerizations have been developed. However, asymmetric cycloisomerizations where a chiral catalyst specifies the stereochemical outcome of the cyclization of a single enantiomer substrate—regardless of its inherent preference—are unknown. Here we show how a combined theoretical and experimental approach enables the design of a highly reactive rhodium catalyst for the stereoselective cycloisomerization of ynamide-vinylcyclopropanes to [5.3.0]-azabicycles. We first establish highly diastereoselective cycloisomerizations using an achiral catalyst, and then explore phosphoramidite-complexed rhodium catalysts in the enantioselective variant, where theoretical investigations uncover an unexpected reaction pathway in which the electronic structure of the phosphoramidite dramatically influences reaction rate and enantioselectivity. A marked enhancement of both is observed using the optimal theory-designed ligand, which enables double stereodifferentiating cycloisomerizations in both matched and mismatched catalyst–substrate settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

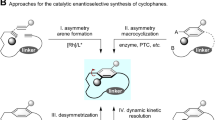

Demand for higher efficiency, economy and selectivity in the synthesis of novel molecular scaffolds drives organic chemistry1,2. In this context, cycloisomerizations represent ideal methods for the formation of cyclic organic molecules, as they can fulfil all of these criteria. Despite much research into transition metal-catalysed cycloisomerization3,4, and reports where high enantioselectivity is achieved for the cyclization of prochiral substrates to enantioenriched products5,6, this important field of synthetic methodology has neglected the development of enantiospecific diastereoselective transformations, where single enantiomer starting materials are subjected to asymmetric cycloisomerization to give specific diastereomer products (that is, double stereodifferentiation, where catalyst and substrate stereocontrol compete)7,8,9,10. In an age where absolute control of molecular substitution and stereochemistry is paramount for applications, the realization of such processes would represent a major advance in the sustainable synthesis of precision-manufactured target molecules.

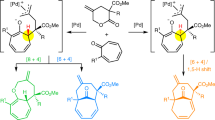

Here we describe rationally designed cycloisomerization catalysts that address these challenges. The reaction selected for this study was the [5+2] cycloisomerization of ynamide-vinylcyclopropanes to [5.3.0] azabicycles (1→2, 3, Fig. 1). Although [5+2] processes have a rich history in the field of alkyne-vinylcyclopropanes11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22, the development of this process using ynamides—or indeed any asymmetric cycloisomerization of ynamide-tethered enynes—has not been explored either experimentally or theoretically23,24,25,26,27. More generally, we question whether a catalyst system optimized to achieve an enantioselective cyclization (1→2, Fig. 1b) can translate to a double stereodifferentiating setting (1→3 or epi- 3, Fig. 1c), particularly should the catalyst be required to overcome powerful substrate stereocontrol. Intrinsic to these studies is a combined theoretical and experimental approach to optimize catalyst design28,29,30, which in the event reveals an unexpected mechanistic pathway for rhodium-catalysed [5+2] carbocyclizations (Fig. 1a). This work demonstrates the powerful role of density functional level of theory (DFT) computations in understanding asymmetric catalysis, leading to quantitative computational-led design of new, highly selective ligands.

(a) We show that mechanistic calculations are crucial in the design of an enantioselective cycloisomerization catalyst. (b) Enantioselective higher order ynamide cycloisomerization is realized. (c) Despite high levels of substrate stereocontrol, the computationally designed catalyst is able to define product stereochemistry.

Results

Substrate synthesis and reaction optimization

A selection of ynamide cycloisomerization substrates 1 were readily accessed from allylic esters 4 (Fig. 2) by an Ireland-Claisen/Curtius rearrangement/ynamide formation sequence. Substituents could be introduced at one or both of the carbon atoms on the ene-ynamide backbone, and by incorporating an enzymatic resolution into this synthesis, enantioenriched ynamides could be prepared. Ynamide formation (6→1) was achieved using copper-catalysed coupling of the sulfonamide with a bromoalkyne32, or via formation of an intermediate dichloroenamide33. Initial screening of ruthenium14 and rhodium20,34 catalyst systems (Table 1) revealed that only the latter afforded high yields of azabicycle 7a from ynamide 1a; using [Rh(cod)naphthalene]SbF6 (5 mol%) as the catalyst35,36, the cycloisomerization could be effected within 3 h at room temperature, giving 7a in 91% yield (Entry 6).

(a) The synthetic route employed uses an Ireland-Claisen rearrangement of esters 4a–e to construct the vinylcyclopropane and install up to two backbone substituents; subsequent Curtius rearrangement/sulfonylation converts the carboxylic acids 5 to sulfonamides 6; ynamide formation is then achieved using copper-catalysed coupling with a bromoalkyne or, for hindered or aniline-derived ynamides, a two step route via a dichloroenamide. For the preparation of enantioenriched esters 4b, 4d and 4e, and ynamides 1q and 1s, see Supplementary Fig. 4. (b) Ynamide-vinylcyclopropanes prepared using this strategy.

Substrate scope

A variety of ynamides 1a–s were now examined in the cycloisomerization using these optimized conditions (Fig. 3). Aryl-substituted ynamides 1b–d reacted with high efficiency, and revealed a clear electronic effect on the reaction rate, with electron-deficient ynamides 1b and 1c showing reduced reaction times. Alkyl-substituted ynamides 1e–g also displayed enhanced reactivity compared with phenyl ynamide 1a, affording the corresponding [5.3.0]-azabicycles 7e–g in excellent yields within 15 min at ambient temperature. Similar efficient reactivity was observed for the cyclization of the heteroaryl-substituted ynamides 1h and 1i to the indolyl- and pyrrolyl-substituted products 7h and 7i. The mild conditions of the reaction are emphasized by the cyclization of the aniline-derived ynamide 1j, which led to tricycle 7j in 74% yield—notably, this 1,4-diene did not undergo in situ isomerization to the indole.

Of clear interest was the level of substrate stereocontrol that might be achieved using ynamides 1l–s. Excellent levels of substrate stereoinduction were observed, with products 7l–s afforded in high yield and as single diastereomers for substrates featuring an allylic stereocenter; and, for 7s, as a single regioisomer as well as diastereoisomer14. Cyclization of substrates containing homoallylic stereocenters proved less selective; however, good stereoselectivity (dr=12:1) could be achieved using [Rh(cod)Cl]2. These collected results are significant in the wider context of [5+2] cycloisomerization, where high levels of substrate stereocontrol have previously been generally interpreted to arise from an `inside alkoxy effect' from oxygen-bearing stereocenters allylic to the vinylcyclopropane37,38. In this work, it is apparent that such stereoelectronic effects are not a prerequisite for high stereoselectivity.

Enantioselective cycloisomerization

In targeting an asymmetric version of the cyclization, we were mindful of the excellent asymmetric [5+2] Rh-catalysed cycloisomerization of alkyne-vinylcyclopropanes described by Shintani et al.39,40, which employed the versatile phosphoramidite ligand L1 (Fig. 4a)41. A preliminary screen of a range of phosphoramidite ligands L1–L4 revealed that L1 indeed seemed optimal for the enantioselective cycloisomerization of ynamide-vinylcyclopropane 1a, delivering product (–)-7a in excellent yield and enantioselectivity (96%, 98% ee) after just 15 min at room temperature (see Supplementary Information for assignment of absolute stereochemistry). However, forays with other substrates suggested that this ligand might not meet our expectations in more challenging settings, and we realized that any further advance would require a combined theoretical and experimental design approach.

(a) A selection of phosphoramidite ligands screened reveals a strong dependence of enantioselectivity and reaction rate on amine and BINOL components' structure and chirality, with L1 giving superior results. (b) The Shintani–Hayashi model for enantioselectivity is based on a crystal structure of [L1 Rh(norbornadiene)]+. (c) Our calculations (Fig. 5) support an alternative mode of binding of the ynamide, and an alternative reaction pathway that initiates with rhodacyclopentene formation. Re face binding of the vinylcyclopropane is favoured, with calculated structures, and activation barriers (kcal mol−1)/selectivities depicted (distances in Å). (d) A transition state model is shown that identifies key ligand design parameters. (e) Variation of the electronic character of the η2-bound arene of the phosphoramidite leads to predicted enantioselectivies for L5 (p-F) and L6 (p-OMe), and an excellent correlation of experiment and theory for L1 and L4.

To this end, we conducted a computational exploration of the reaction pathway, which began with investigation of the empirical model adopted by Shintani et al. to explain the enantioselectivity of vinylcyclopropane-alkyne cycloisomerization. This model (Fig. 4b) is based on an X-ray crystal structure of [Rh(L1) norbornadiene]BF4 reported by Mezetti (8) (ref. 42), which reveals an η2-complexation of one of the α-methylbenzylamine arenes to the rhodium cation—the phosphoramidite thus acting as a bidentate ligand. The Shintani–Hayashi model docks the vinylcyclopropane-alkyne onto this ligated rhodium framework as in structure 9, such that the alkyne coordinates trans to the phosphorous atom of the phosphoramidite ligand, and the vinylcyclopropane coordinates trans to the η2-complexed arene, with an orientation that minimizes steric interactions between the cyclopropane ring and naphthyl group.

Computational study and ligand optimization

Computation, particularly at the DFT level, has emerged as a powerful tool for assessing the feasibility of mechanistic steps involved in catalysis43. Our theoretical work first explored eight possibilities for the binding of ynamide-vinylcyclopropane 1a to the [Rh(L1)] cation (Table 2). In contrast to the Shintani–Hayashi model, this suggested that the lowest energy complex of [Rh(L1)1a] positions the ynamide proximal to the naphthyl ring and trans- to the arene ligand, and the vinylcyclopropane trans- to the phosphorous atom (10, Fig. 5, P-trans-ene/Up). The next lowest energy structure maintains this positional selectivity of substrate binding, but inverts its orientation (that is, P-trans-ene/Down). Next, calculations were carried out to explore the two widely accepted mechanisms for [5+2] cycloisomerization, which initiate either with an oxidative addition into the vinylcyclopropane, followed by alkyne insertion into the resultant σ/π-allyl rhodium(III) complex 11 to give eight-membered rhodacycle 12 (vinylcyclopropane pathway), or via oxidative cycloaddition of Rh(I) with the alkyne and alkene to give rhodacyclopentene 13, followed by ring expansion into the cyclopropane to give the same intermediate 12 (metallacyclopentene pathway). Where investigations by Yu, Houk and Wender on Rh-catalysed [5+2] cycloisomerizations suggest that oxidative addition into the vinylcyclopropane is the first step on the catalytic pathway17,21, our DFT calculations (Fig. 5) suggest that oxidative coupling of the alkene-ynamide to form metallacyclopentene 13 appears to be the preferred reaction pathway for an ynamide-vinylcyclopropane to give 12, followed by ring expansion of the cyclopropane. Notably, this mechanism has also been calculated to be the preferred pathway in ruthenium-catalysed [5+2] cycloisomerization17. The preference for this pathway over vinylcyclopropane oxidative addition is in the range of 4–12 kcal mol−1, depending on the orientation with which 1a binds to the [Rh(L1)] cation; notably, the transition states for both pathways favour Re-face binding of the alkene in a P-trans-ene/Down orientation. This sequence of steps is favoured in this intramolecular reaction due to additional stabilization of the forming Rh(III) intermediate in the oxidative coupling step by the electron-rich ynamide. The free energy profile for the catalytic cycle is exergonic by more than 40 kcal mol−1, and product inhibition is predicted to be minimal, since the reactant preferentially binds to the catalyst by 6.2 kcal mol−1; taken together with a turnover and selectivity determining barrier of 17.0 kcal mol−1 for the metallacyclopentene pathway, our computations are consistent with the short reaction times observed at room temperature for the conversion of 1a–7a using L1.

Complex 10 (Re face binding) is found to be the lowest energy ground state for ynamide complexation, and transition state for oxidative coupling (metallacyclopentene pathway, see Table 2). The calculated energy profiles of the cycloisomerization for Re-face (black, bold) and Si-face (grey) substrate association via pathways initiating with metallacyclopentene formation (left), or vinylcyclopropane insertion (right) are illustrated; the former is favoured. SMD-ωB97XD/6-311+G(d,p)/Lanl2TZ//ωB97XD/6-31G(d)/Lanl2DZ Gibbs free energies are shown in kcal mol−1.

The lowest energy transition state for the oxidative coupling of this metallacyclopentene pathway (TS3) is illustrated in Fig. 4c. This transition state leads to a calculated enantioselectivity for cyclization with ligand L1 of 97.9% ee (ΔΔG‡Re/Si=–2.69 kcal mol−1), which is in excellent agreement with the experimental value (R, 98% ee). The calculated enantioselectivity for phosphoramidite L4 (9.3% ee, ΔΔG‡Re/Si=–0.11 kcal mol−1) also correlates well with the poor selectivity we had already observed experimentally with this ligand (7% ee), supporting the mechanistic model, and implying that the naphthyl ring plays a crucial role—likely related (for aryl ynamides) to a stabilizing dispersive (π−π) interaction between the ynamide substituent and the naphthyl group in TS3. Although partial saturation of the naphthyl backbone (that is, in L4) leads to higher activation barriers, it is notable that the erosion of enantioselectivity for this ligand results from a greater increase (by 2.58 kcal mol−1) to the activation barrier for Re-face addition compared with Si-face addition; this supports the existence, and importance, of stabilizing non-bonding (dispersion) interactions because of the aromatic backbone of L1 in favouring the major enantiomer. Alkyl substituents are expected to experience similar attractive non-bonding interactions (CH–π); these interactions are further evident from an analysis of the computed non-covalent interaction index (Supplementary Fig. 68).

The oxidative coupling (TS3) is the rate-limiting and enantioselectivity determining step in this rhodacyclopentene mechanism. As observed in the Mezetti norbornene crystal structure (Fig. 4b)42, one of the ligand benzylamine groups acts as 2π-electron donor (2.6–2.7 Å) in these transition states. We hypothesized that variation of the electronic character of this η2-complexed arene could dramatically influence both the rate, and selectivity, of the reaction. Calculations on the effect of electronically-biasing methoxy and fluoro groups at the para position of these arenes suggested that decreasing the electron density on the arene (p-F, L5, Fig. 4d,e) would lead to an increase in reaction rate (ΔΔG‡L5/L1=−0.47 kcal mol−1) and enantioselectivity (ΔΔG‡Re/Si=–4.56 kcal mol−1, 99.9% ee), while an electron-donating substituent (p-MeO, L6) would have the opposite effect (ΔΔG‡L6/L1=+0.76 kcal mol−1, ΔΔG‡Re/Si=–2.42 kcal mol−1, 96.7% ee). This computed trend in reactivity and enantioselectivity, namely L5>L1>L6, results from a weakened metal-arene interaction in the TS leading to the major enantiomer, which is compensated for through stronger coordination of the alkynyl and alkenyl groups (see Supplementary Information for further details and discussion). These ligand structural modifications also modulate the Lewis basicity at phosphorus, however preferential stabilization of the major enantiomeric pathway confirms that the predominant effect is not inductive in nature, but rather depends on through-space interactions involving the Rh-coordinating aryl group.

Substrate scope in the asymmetric cycloisomerization

While phosphoramidite L6 is known, (ref. 44) L5 is not, but could be readily synthesized using standard methods45. Both were evaluated in the enantioselective cyclization alongside L1 (Fig. 6a). To our delight, experiment correlated well with the predicted outcomes of these cyclizations; the p-fluorobenzyl ligand L5 indeed showed a dramatic enhancement of rate and selectivity in the cyclization of 1a compared with the parent ligand L1, affording 7a in under 5 min with 99% ee (calc. 99.9% ee), while the p-methoxybenzyl ligand L6 exhibited a much reduced rate of reaction, and also lower enantioselectivity (1 h, 97% ee, calc. 96.7% ee). The cyclization of alkyl-substituted ynamides 1e–g to give enantioenriched azabicycles 7e–g also showed a rate and selectivity enhancement between L1 and L5. The potent reactivity of the latter ligand was extended to a variety of aryl-substituted ynamides, where the marked rate difference between electron-poor (1b) and electron-rich (1d) ynamides supports the hypothesis that the ynamide is intimately involved in the rate-determining step (that is, a metallacyclopentene pathway). In all cases using ligand L5, these reactions proceeded in under 30 min with excellent levels of enantioselectivity (94–99% ee); furthermore, the synthesis of 7e could be achieved on a 1 mmol scale in less than 5 min with 1.25 mol% catalyst loading. Monitoring of reaction conversion by 1H NMR spectroscopy (in CDCl3, Fig. 6b) emphasizes the dramatic rate difference between these three ligands, with the reaction using L5 complete in under 4 min, compared with the slower cyclizations with L1 and L6 (addition of the catalyst solution to the substrate followed by NMR spectroscopic analysis necessitated a four minute delay between reaction initiation and acquisition of the first NMR spectrum. The reaction catalysed by [L5Rh] was complete by this time).

(a) Enantioselective cyclization is tested against a range of ynamide-vinylcyclopropanes, showing an excellent correlation of computation and experiment for the theory-designed ligands L5 and L6. The synthesis of 7e was performed on 1 mmol scale (1.25 mol% catalyst). (b) 1H NMR spectroscopic monitoring of reaction progress emphasizes the rate enhancement between ligands L6, L1 and L5, also predicted theoretically. (c) Matched double stereodifferentiating cycloisomerizations proceed with high selectivity and rate. (d) Mismatched double stereodifferentiating cycloisomerizations proceed successfully under catalyst stereocontrol using the enantiomers of ligands L1, L5 and L6 (that is, (R,S,S)-L stereochemistry); the major diastereomer is shown. The a signifies reaction conversion, as judged by 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis.

Finally, the performance of these ligands was tested against the challenge of cyclizations that proceed with high levels of substrate stereocontrol, to address the question of how a high enantioselectivity-inducing catalyst would cope with mismatched substrate-catalyst diastereoselective cycloisomerization scenarios. Three substrates were chosen for this challenge: ynamides 1l, 1q and 1r, which gave >20:1, 1.8:1 and >20:1 dr, respectively when cyclized using [Rh(cod)naphthalene]SbF6 (Fig. 3). As expected, these single enantiomer substrates cyclized rapidly, and with high efficiency and selectivity, with the matched substrate-catalyst combination (that is, (S,R,R)-L5, Fig. 6c). To our delight, we found that cycloisomerization of substrate 1l using the enantiomeric catalyst system ((R,S,S)-L1) successfully overturned this powerful substrate stereoselectivity, giving 14l in up to 1:8 dr. Interestingly, it was ligand L1—and not L5—which performed optimally in this challenging situation, albeit requiring an extended reaction time. In the case of 1q, the catalyst (with either L1 or L5) was able to achieve an equivalent (reversed) level of selectivity to that achieved in the matched sense—in this instance, a modest level of inherent substrate stereocontrol being completely overturned. Finally, the most challenging setting of the reinforcing substituents in 1r proved a hurdle that could also be partly overcome, again demonstrating significant catalyst influence.

These observations may suggest that tighter substrate-Rh complexation in the case of L5 (a consequence of a slightly weaker ligand-metal interaction observed in our calculations (see Supplementary Information for details), which improves rate and enantioselectivity), enhances unfavourable (that is, mismatched) steric effects in a double stereodifferentiating setting such that it effectively increases the stereocontrolling influence of the substrate relative to that of the ligand. The most reactive/selective catalysts for enantioselective cyclizations could thus suffer from higher than expected transition state energies in diastereoselective cyclizations, where such steric effects are enhanced compared with `less enantioselective' catalysts (looser substrate binding); and that different considerations are therefore needed in the development of double stereodifferentiating reactions, with more ‘promiscuous’ catalysts potentially giving superior selectivity.

Discussion

In summary, the first example of an enantioselective ynamide-tethered cycloisomerization has been achieved, with a series of highly enantio- and diastereoselective cyclizations giving a range of substituted/enantioenriched [5.3.0] azabicycles. Theoretical reaction analysis crucially influenced ligand design, leading to a catalyst system that displayed enhanced rate and enantioselectivity in the cycloisomerization. The demonstration of the first successful examples of enantiospecific diastereoselective transition metal-catalysed cycloisomerizations in a significantly mismatched substrate-catalyst environment illustrates that cycloisomerization can assemble functionalized ring systems with tuneable selectivity. These studies set the stage for the development of further computationally guided catalyst systems.

Methods

Racemic [5+2] cycloisomerization

To an oven-dried vial containing the ynamide vinylcyclopropane (1.0 equiv.) under Ar was added a solution of [(C10H8)Rh(cod)]SbF6 (5 mol%) in degassed CH2Cl2 (10 ml mmol−1 of ynamide). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature under Ar until consumption of the ynamide was observed by thin layer chromatography (see Fig. 3 for reaction times). The reaction mixture was then concentrated, and the resulting material was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2, petroleum ether/ethyl acetate eluent) (Fig. 3).

Asymmetric [5+2] cycloisomerization

A solution of [RhCl(C2H4)2]2 (2.5 mol%), NaBArF4 (6 mol%) and phosphoramidite ligand (6 mol%) in degassed CH2Cl2 (10 ml mmol−1 of ynamide) was stirred for 20 min under Ar. The solution was filtered (through a PTFE filter-tipped syringe) into an oven-dried vial containing ynamide vinylcyclopropane (1.0 equiv.) under Ar. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature under Ar until consumption of the ynamide was observed by thin layer chromatography (see Fig. 6 for reaction times). The reaction mixture was then concentrated, and the resulting material was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2, petroleum ether/ethyl acetate eluent) (Fig. 6).

Computational methods

Molecular geometries were fully optimized at the DFT theory level in Gaussian 09 (rev. D.01), using the dispersion-corrected ω-B97XD functional46 without symmetry constraints. The effective core potentials (ECPs) of Hay and Wadt47 with a double-ζ basis set (LanL2DZ) were used for Rh, S and P, and the 6-31G(d) basis set was used for H, C, N and O(BS1). The energies were further estimated using a larger basis set (6-311+G (d, p) basis set for H, C, N, O, S and P) and triple-ζ basis set (LanL2TZ)48 for Rh (BS2) by single-point calculations, in implicit solvent CH2Cl2 treated with the SMD universal solvation models49. The structures of the ynamide substrate and a series of phosphoramidite ligands were computed in full, while the toluenesulfonamide p-tolyl group was modelled as a methyl group in the interests of computational tractability. See Supplementary Methods for further details.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Straker, R. N. et al. Computational ligand design in enantio- and diastereoselective ynamide [5+2] cycloisomerization. Nat. Commun. 7:10109 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10109 (2016).

References

Newhouse, T., Baran, P. S. & Hoffmann, R. W. The economies of synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 3010–3021 (2009).

Trost, B. M. The atom economy–a search for synthetic efficiency. Science 254, 1471–1477 (1991).

Michelet, V., Toullec, P. Y. & Genet, J. P. Cycloisomerization of 1,n-enynes: challenging metal-catalyzed rearrangements and mechanistic insights. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 4268–4315 (2008).

Inglesby, P. A. & Evans, P. A. Stereoselective transition metal-catalysed higher-order carbocyclisation reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 2791–2805 (2010).

Marinetti, A., Jullien, H. & Voituriez, A. Enantioselective, transition metal catalyzed cycloisomerizations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 4884–4908 (2012).

Watson, I. D. G. & Toste, F. D. Catalytic enantioselective carbon-carbon bond formation using cycloisomerization reactions. Chem. Sci. 3, 2899–2919 (2012).

Feducia, J. A., Campbell, A. N., Doherty, M. Q. & Gagné, M. R. Modular catalysts for diene cycloisomerization: Rapid and enantioselective variants for bicyclopropane synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 13290–13297 (2006).

Ham, Y. J., et al. Rhodium-catalyzed reductive cyclization of 1,6-enynes and stereoselective synthesis of the putative structure of lucentamycin A and its stereoisomers. Tetrahedron 68, 1918–1925 (2012).

Lei, A. & He, M. Zhang, X., Rh-catalyzed kinetic resolution of enynes and highly enantioselective formation of 4-alkenyl-2,3-disubstituted tetrahydrofurans. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 11472–11473 (2003).

Trost, B. M., Ryan, M. C. & Rao, M. Markovic, T. Z., Construction of enantioenriched [3.1.0] bicycles via a ruthenium-catalyzed asymmetric redox bicycloisomerization reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 17422–17425 (2014).

Wender, P. A., Takahashi, H. & Witulski, B. Transition metal catalyzed [5+2] cycloadditions of vinylcyclopropanes and alkynes: a homolog of the Diels-Alder reaction for the synthesis of seven-membered rings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 4720–4721 (1995).

Wender, P. A. et al. Transition metal-catalyzed [5+2] cycloadditions with substituted cyclopropanes: first studies of regio- and stereoselectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 10442–10443 (1999).

Trost, B. M., Toste, F. D. & Shen, H. Ruthenium-catalyzed intramolecular [5+2] cycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 2379–2380 (2000).

Trost, B. M. et al. Syntheses of seven-membered rings: ruthenium-catalyzed intramolecular [5+2] cycloadditions. Chem. Eur. J. 11, 2577–2590 (2005).

Pellissier, H. Recent developments in the [5+2] cycloaddition. Adv. Synth. Catal. 353, 189–218 (2011).

Ylijoki, K. E. O. & Stryker, J. M. [5+2] Cycloaddition reactions in organic and natural product synthesis. Chem. Rev. 113, 2244–2266 (2013).

Mustard, T. J. L., Wender, P. A. & Cheong, P. H.-Y. Catalytic efficiency is a function of how rhodium(I) (5+2) catalysts accommodate a conserved substrate transition state geometry: induced fit model for explaining transition metal catalysis. ACS Catal. 5, 1758–1763 (2015).

Hong, X., Trost, B. M. & Houk, K. N. Mechanism and origins of selectivity in Ru(II)-catalyzed intramolecular (5+2) cycloadditions and ene reactions of vinylcyclopropanes and alkynes from density functional theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 6588–6600 (2013).

Xu, X. et al. Ligand effects on rates and regioselectivities of Rh(I)-catalyzed (5+2) cycloadditions: a computational study of cyclooctadiene and dinaphthocyclooctatetraene as ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 11012–11025 (2012).

Liu, P. et al. Electronic and steric control of regioselectivities in Rh(I)-catalyzed (5+2) cycloadditions: experiment and theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 10127–10135 (2010).

Liu, P., Cheong, P. H.-Y., Yu, Z.-X., Wender, P. A. & Houk, K. N. Substituent effects, reactant preorganization, and ligand exchange control the reactivity in RhI-catalyzed (5+2) cycloadditions between vinylcyclopropanes and alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 3939–3941 (2008).

Yu, Z.-X., Wender, P. A. & Houk, K. N. On the Mechanism of [Rh(CO)2Cl]2-Catalyzed Intermolecular (5+2) Reactions between Vinylcyclopropanes and Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 9154–9155 (2004).

Walker, P. R., Campbell, C. D., Suleman, A., Carr, G. & Anderson, E. A. Palladium- and ruthenium-catalyzed cycloisomerization of enynamides and enynhydrazides: A rapid approach to diverse azacyclic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 9139–9143 (2013).

Couty, S., Meyer, C. & Cossy, J. Diastereoselective gold-catalyzed cycloisomerizations of ene-ynamides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 6726–6730 (2006).

Witulski, B. & Alayrac, C. A highly efficient and flexible synthesis of substituted carbazoles by rhodium-catalyzed inter- and intramolecular alkyne cyclotrimerizations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 3281–3284 (2002).

Wang, X.-N. et al. Ynamides in ring forming transformations. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 560–578 (2014).

Nishimura, T., Takiguchi, Y. & Maeda, Y. Hayashi, T., Rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric cycloisomerization of 1,6-ene-ynamides. Adv. Synth. Catal. 355, 1374–1382 (2013).

Tsang, A. S. K., Sanhueza, I. A. & Schoenebeck, F. Combining experimental and computational studies to understand and predict reactivities of relevance to homogeneous catalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 16432–16441 (2014).

Nielsen, M. C., Bonney, K. J. & Schoenebeck, F. Computational ligand design for the reductive elimination of ArCF3 from a small bite angle PdII complex: remarkable effect of a perfluoroalkyl phosphine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 5903–5906 (2014).

Sperger, T., Sanhueza, I. A., Kalvet, I. & Schoenebeck, F. Computational studies of synthetically relevant homogeneous organometallic catalysis involving Ni, Pd, Ir, and Rh: An overview of commonly employed DFT methods and mechanistic insights. Chem. Rev 115, 9532–9586 (2015).

Kocienski, P. J., Christopher, J. A., Bell, R. & Otto, B. Nucleophilic addition of α-metallated carbamates to planar chiral cationic η3-allylmolybdenum complexes: a stereochemical study. Synthesis 75–84 (2005).

Zhang, X. et al. Copper(II)-catalyzed amidations of alkynyl bromides as a general synthesis of ynamides and Z-enamides. An intramolecular amidation for the synthesis of macrocyclic ynamides. J. Org. Chem. 71, 4170–4177 (2006).

Mansfield, S. J., Campbell, C. D., Jones, M. W. & Anderson, E. A. A robust and modular synthesis of ynamides. Chem. Commun. 51, 3316–3319 (2015).

Saito, A., Ono, T. & Hanzawa, Y. Cationic Rh(I) catalyst in fluorinated alcohol: mild intramolecular cycloaddition reactions of ester-tethered unsaturated compounds. J. Org. Chem. 71, 6437–6443 (2006).

Wender, P. A. & Williams, T. J. [(arene)Rh(cod)]+ Complexes as catalysts for [5+2] cycloaddition reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 4550–4553 (2002).

Wender, P. A. et al. Structural complexity through multicomponent cycloaddition cascades enabled by dual-purpose, reactivity regenerating 1,2,3-triene equivalents. Nat. Chem 6, 448–452 (2014).

Trost, B. M., Shen, H. C., Schulz, T., Koradin, C. & Schirok, H. On the diastereoselectivity of Ru-catalyzed [5+2] cycloadditions. Org. Lett. 5, 4149–4151 (2003).

Trost, B. M., Waser, J. & Meyer, A. Total synthesis of (−)-pseudolaric acid B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 16424–16434 (2008).

Shintani, R., Nakatsu, H., Takatsu, K. & Hayashi, T. Rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric [5+2] cycloaddition of alkyne-vinylcyclopropanes. Chem. Eur. J. 15, 8692–8694 (2009).

Wender, P. A., et al. Asymmetric catalysis of the [5+2] cycloaddition reaction of vinylcyclopropanes and π-systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 6302–6303 (2006).

Teichert, J. F. & Feringa, B. L. Phosphoramidites: Privileged ligands in asymmetric catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 2486–2528 (2010).

Mikhel, I. S. et al. A chiral phosphoramidite beyond monodentate coordination: Secondary pi-interactions turn a dangling aryl into a two-, four-, or six-electron donor in d(6) and d(8) complexes. Organometallics 27, 2937–2948 (2008).

Cheng, G.-J., Zhang, X., Chung, L. W., Xu, L. & Wu, Y.-D. Computational organic chemistry: bridging theory and experiment in establishing the mechanisms of chemical reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 1706–1725 (2015).

Polet, D. & Alexakis, A. Kinetic study of various phosphoramidite ligands in the iridium-catalyzed allylic substitution. Org. Lett. 7, 1621–1624 (2005).

Roth, P. M. C., Sidera, M., Maksymowicz, R. M. & Fletcher, S. P. Copper-catalyzed asymmetric conjugate addition of alkylzirconium reagents to cyclic enones to form quaternary centers. Nat. Protoc. 9, 104–111 (2014).

Chai, J. D. & Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom-atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 6615–6620 (2008).

Wadt, W. R. & Hay, P. J. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for main group elements Na to Bi. J. Chem. Phys. 82, 284–298 (1985).

Roy, L. E., Hay, P. J. & Martin, R. L. Revised basis sets for the LANL effective core potentials. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 1029–1031 (2008).

Marenich, A. V., Cramer, C. J. & Truhlar, D. G. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 6378–6396 (2009).

Acknowledgements

E.A.A. and R.N.S. thank the EPSRC (EP/K005391/1, EP/H025839/1 and a studentship to R.N.S. (EP/K503113/1)) for support. R.S.P. thanks the Chemical Structure Association Trust, and Q.P. thanks the European Community (FP7-PEOPLE-2012-IIF under grant agreement 330364) for support. We acknowledge the use of the EPSRC UK National Service for Computational Chemistry Software (CHEM773) in carrying out this work. A.M. thanks the Royal Thai Government and the DPST project for a studentship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.A.A. and R.N.S. conceived of the synthetic methodology. R.N.S. carried out the experimental work, with the aid of A.M. Q.P. and R.S.P. carried out the theoretical calculations. R.N.S., E.A.A., Q.P. and R.S.P. analysed the collected results. E.A.A., R.N.S., Q.P. and R.S.P. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-68, Supplementary Tables 1-2, Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 3852 kb)

Supplementary Data 1

xyz coordinates for computational modelling (DOCX 160 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Straker, R., Peng, Q., Mekareeya, A. et al. Computational ligand design in enantio- and diastereoselective ynamide [5+2] cycloisomerization. Nat Commun 7, 10109 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10109

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10109

This article is cited by

-

Chiral Brønsted acid-catalyzed asymmetric intermolecular [4 + 2] annulation of ynamides with para-quinone methides

Science China Chemistry (2023)

-

Mechanistic investigation of Rh(i)-catalysed asymmetric Suzuki–Miyaura coupling with racemic allyl halides

Nature Catalysis (2021)

-

Comparing quantitative prediction methods for the discovery of small-molecule chiral catalysts

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2018)

-

Computational design of high-performance ligand for enantioselective Markovnikov hydroboration of aliphatic terminal alkenes

Nature Communications (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.