Abstract

It is well known that many operations in quantum information processing depend largely on a special kind of quantum correlation, that is, entanglement. However, there are also quantum tasks that display the quantum advantage without entanglement. Distinguishing classical and quantum correlations in quantum systems is therefore of both fundamental and practical importance. In consideration of the unavoidable interaction between correlated systems and the environment, understanding the dynamics of correlations would stimulate great interest. In this study, we investigate the dynamics of different kinds of bipartite correlations in an all-optical experimental setup. The sudden change in behaviour in the decay rates of correlations and their immunity against certain decoherences are shown. Moreover, quantum correlation is observed to be larger than classical correlation, which disproves the early conjecture that classical correlation is always greater than quantum correlation. Our observations may be important for quantum information processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Correlations, including classical and quantum parts, are crucial in science and technology. Although many operations in quantum information processing depend largely on a special kind of quantum correlation, that is, entanglement1, there are quantum tasks that display the quantum advantage without entanglement2,3,4, and some of these have been verified experimentally5. Distinguishing classical and quantum correlations is therefore of both fundamental and practical importance. Many theoretical studies have been conducted in this direction6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Among them, quantifying the quantumness of correlations with quantum discord7 has received great attention4,5,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26.

In the field of quantum information, for a bipartite system ρAB, it is widely accepted that quantum mutual information measures its total correlations12,27 defined as I(ρAB)=S(ρA)+S(ρB)−S(ρAB)28, where ρA and ρB are the reduced-density matrices of ρAB. S(ρ)=−trρlog2ρ in the von Neumann entropy. Depending on the maximal information gained for ρAB with measurement on one of the subsystems, classical correlation (C)6 is defined as C(ρAB)≡ [S(ρA)-σjqjS(ρjA)], where Bj†Bj is a positive-operator-valued measure performed on the subsystem B and qj=trAB(BjρABBj†). ρAj=trB(BjρABBj†)/qj is the postmeasurement state of A after obtaining outcome j on particle B. Quantum correlation is therefore given by Q(ρAB)=I(ρAB)−C(ρAB). In such a case, Q is just identical to quantum discord with a definition based on the distinction between classical information theory and quantum information theory7, which can be further distributed into entanglement and the additional quantum correlation (non-entanglement quantum correlation)29.

Because of the unavoidable interaction between a quantum system and its environment, understanding the dynamics of different kinds of correlations has stimulated great interest. Some studies have focused on the comparison between the dynamics of quantum discord and entanglement under both Markovian19 and non-Markovian21,22 environments. Their behaviours have been shown to be very different, and the quantum discord is more robust against decoherence than entanglement in the Markovian evolution19. Recently, several peculiar properties in the dynamics of classical and quantum correlations have also been shown with the presence of Markovian noise23,24, in which the decay rates of correlations may exhibit sudden changes in behaviour23 and the bipartite quantum correlation may completely disappear without being transferred to the environment24.

In this study, we experimentally investigate the dynamics of classical and quantum correlations between biqubit systems in a one-sided phase-damping channel. The sudden changes in behaviours in the decay rates of classical and quantum correlations are shown in an all-optical experimental setup, in which the dephasing environment is simulated by birefringent quartz plates. Classical and quantum correlations are observed to remain unaffected under certain decoherence areas. Moreover, quantum correlation is shown to be larger than classical correlation during the dynamics of a special input state, which contradicts the early conjecture that classical correlation is always greater than quantum correlation30. Our observations may have important roles in quantum information processing.

Results

Theoretical schemes

Consider a two-level quantum system S with lower and upper states |0〉S and |1〉S under the action of a phase-damping environment E(|0〉E is the initial state). The interaction quantum map can be written as31

Under such a uniquely quantum mechanical noise process, the system S remains in the initial state with the probability p of scattering the environment to its excited state |1〉E, if S is in state |0〉S, and to |2〉E, if S is in state |1〉S. It physically describes, for instance, the case when a photon scatters randomly in a fibre. The coherence of S degrades exponentially, and p=1−exp(−Γt), where Γ is the decay rate. When it extends to the case of bipartite systems coupling with this environment, the decoherence-free states32 and the phenomenon of entanglement collapse and revival33 have been shown.

When an initial Bell-diagonal state  , with

, with  and

and  representing the four Bell states and a+b+c+d=1 evolves in the phase-damping channel given by equation (1), its off-diagonal elements decay exponentially according to the previous analysis. Because S(ρA)=S(ρB)=1, the total correlation is calculated as

representing the four Bell states and a+b+c+d=1 evolves in the phase-damping channel given by equation (1), its off-diagonal elements decay exponentially according to the previous analysis. Because S(ρA)=S(ρB)=1, the total correlation is calculated as

where λj are the four eigenvalues of the final density matrix. To calculate the classical correlation6, the state in mode B is projected into |l〉=cosθ|0〉+sinθeiφ|1〉 to get the minimal conditional entropy of subsystem A, where 0≤θ≤π and 0≤φ≤2π. In the biqubit case, the projective measurement is the positive-operator-valued measure to maximize C(ρAB)34, which is expressed as23

represents the conditional entropy of A with projecting B in |l〉 and η=max{|α|,|β|,|γ|} with α=(1−p)(a−b+c−d), β=(1−p)(c−d−a+b) and γ=a+b−c−d. The quantum correlation is therefore given by

Experimental demonstration of the dynamics of correlations

Photon qubits with polarization encoded as the information carriers have been widely used to implement different quantum information processing procedures1. The coupling between photon polarization and frequency modes in a birefringent environment leads to dephase by a trace-over frequency35, which simulates the decoherence effect in equation (1). Here, we encode the horizontal (H) and vertical (V) polarizations of a photon as |0〉S and |1〉S of a qubit and pass the polarization-entangled photons through one-sided controllable quartz plates to investigate the dynamics of different kinds of correlations.

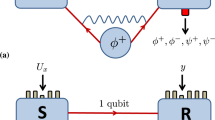

Figure 1 shows our experimental setup. Ultraviolet pulses are frequency doubled from a mode-locked Ti:sapphire laser with wavelength centred at 780 nm, with a 130 fs pulse width and a 76 MHz repetition rate. They are distributed into two paths by an ultraviolet polarization beam splitter, which transmits 45° linearly polarized photons ( ) and reflects −45° linearly polarized photons (

) and reflects −45° linearly polarized photons ( ). The relative power between these two paths can be changed easily by a half-wave plate (HWP1), and the time difference between them is about 6 ns. They then combine again by a beam splitter, and both pump two identically cut type-I β-barium borate crystals, with their optic axes aligned in mutually perpendicular planes, to produce polarization-entangled photon pairs36. After compensating the birefringence effect between H and V with quartz plates (CP), the short pump beam produces the maximally entangled state |φ+〉, whereas the long pump beam produces |φ−〉.

). The relative power between these two paths can be changed easily by a half-wave plate (HWP1), and the time difference between them is about 6 ns. They then combine again by a beam splitter, and both pump two identically cut type-I β-barium borate crystals, with their optic axes aligned in mutually perpendicular planes, to produce polarization-entangled photon pairs36. After compensating the birefringence effect between H and V with quartz plates (CP), the short pump beam produces the maximally entangled state |φ+〉, whereas the long pump beam produces |φ−〉.

Ultraviolet (UV) pulses are divided into two parts by the ultraviolet polarization beam splitter (UV PBS). The relative power between them can be changed by a half-wave plate (HWP1). Entangled photon pairs are prepared by spontaneous parametric down conversion by pumping the two adjacent crystals (β-barium borate, BBO). Quartz plates (CP) are used to compensate the birefringence of down conversion photons, both of which then pass through half-wave plates (HWP2 and HWP4) with the optic axes set at 22.5°. The photon in mode A further passes through a half-wave plate (HWP3) with the optic axis set as horizontal to prepare the required mixed state. The dephasing environment is simulated by quartz plates (Q) with thickness L. An unbalanced Mach–Zehnder device in the dotted pane with the reflective part further passing through two half-wave plates (HWP) is inserted into mode B to prepare another initial mixed state. Quarter-wave plates (QWP), half-wave plates (HWP) and polarization beam splitters (PBS) are used in each mode to set the detecting bases for implementing state tomography. Single-photon detectors equipped with interference filters (IF) are used to detect the photons.

Two HWPs (HWP2 and HWP4), with the optic axes set to 22.5°, can change H into  and V into

and V into  . The HWP (HWP3) with the optic axis set as horizontal in mode A is used to introduce the π-phase between H and V. As our detection traces over the time difference between these two production processes, as has been shown earlier37,38, the prepared state becomes

. The HWP (HWP3) with the optic axis set as horizontal in mode A is used to introduce the π-phase between H and V. As our detection traces over the time difference between these two production processes, as has been shown earlier37,38, the prepared state becomes

where b is determined by the relative power between these two pump beams and b+d=1. Thereafter, the photon in mode A with frequency distribution f(ω) passes through the dephasing channel, which is simulated by quartz plates (Q), with the optic axis set to be horizontal and with a thickness of L. Therefore, the decoherence parameter  imposes on the off-diagonal elements of equation (5), where τ=LΔn/c, with c representing the vacuum velocity of the photon and Δn is the difference between the indices of refraction of H and V. In this case, we obtain p=1−|κ| in equation (1).

imposes on the off-diagonal elements of equation (5), where τ=LΔn/c, with c representing the vacuum velocity of the photon and Δn is the difference between the indices of refraction of H and V. In this case, we obtain p=1−|κ| in equation (1).

An unbalanced Mach–Zehnder device in the dotted pane, which further separates the photon into long and short paths, is inserted into mode B to prepare another input state. The long path in the dotted pane contains a HWP with the optic axis set at 45° and another HWP with the optic axis set as horizontal. The time difference between these two paths is much larger than the coherent time of the photon and less than the coincidence window of the logic circuit (at about 3 ns). As a result, the prepared state becomes

where R is the effective total reflectivity of the two partial reflecting mirrors in the dotted pane. The photon in mode A then further passes through the dephasing channel. Finally, the evolved state is reconstructed by tomography. Quarter-wave plates, HWPs and polarization beam splitters are used in each mode to set the usual 16 measurement bases39. These two photons are detected by single-photon detectors equipped with 3 nm (full width at half maximum) interference filters.

Figure 2 shows the correlation dynamics of input state (5) with b=0.75 in the phase-damping channel. Theoretically, the minimum of conditional entropy S(ρlA) in mode A is obtained by projecting the photon in mode B onto |l〉=cosθ|H〉+sinθeiφ|V〉, with optimization over the angles θ and φ. In our experiment, we measured S(ρlA) as a function of θ with φ=0 in different thicknesses of quartz plates, as shown in Fig. 2a. We found that the minimum value of S(ρlA) is obtained with θ=45° at about L<138λ0 and θ=0° at about L≥138λ0 (λ0=0.78 μm is the central wavelength of the photon), which agree well with theoretical predictions (solid lines)23. This implies that there is a sudden change in behaviour in the decay rate of C according to equation (3). The dynamics of total correlation (I), classical correlation (C) and quantum correlation (Q) are shown in Fig. 2b. We find that C (black squares) decays monotonically at L<138λ0 and then remains constant at L≥138λ0, which agrees with Fig. 2a. Such immunity of classical correlation against decoherence implies an operational way to compute classical and quantum correlations23. In contrast, Q (red dots) behaves in the opposite manner; it remains constant at L<138λ0 and decays monotonically at L≥138λ0. C and Q overlap at the specific thickness of about L=138λ0. It is interesting to observe the 'decoherence-free' area of quantum correlation, which is due to the equal decay rate of I and C. This phenomenon is later shown explicitly in theory by Mazzola et al.40. It may have important applications for those quantum information protocols using only quantum correlation. We can see that I (green upward-pointing triangles) decays exponentially all the time, which is consistent with the continuous dynamics of quantum mutual information according to equation (2). The green solid line, black solid line and red dashed line are the corresponding theoretical predictions of the total, classical and quantum correlations. Error bars correspond to counting statistics.

(a) The values of conditional entropy S(ρlA), with photons evolving in different thicknesses of quartz plates (L), as a function of the measurement angle θ in mode B. (b) The dynamics of correlations. Green upward-pointing triangles, black squares, red dots, blue stars and magenta downward-pointing triangles represent experimental results of I, C, Q, En and Rn, with the green solid line, black solid line, red dashed line, blue dotted line and magenta dotted line representing the corresponding theoretical predictions. Non-entanglement quantum correlation (D) is further compared with C in the inset (the x axis represents the total thickness of quartz plates and the y axis denotes different kinds of correlations). Purple dots represent the experimental results of D and the purple dotted line is the corresponding theoretical prediction. Error bars correspond to counting statistics. λ0=0.78 μm.

The dynamics of entanglement is also shown in Fig. 2b, which is characterized by both the entanglement of formation (En)41 and the relative entropy of entanglement (Rn)42 (the analytical expressions of both characterizations in our case are given in Methods). The blue stars in Fig. 2b are the experimental results of En and the blue dotted line is the corresponding theoretical prediction. The value of entanglement is set to 0 at a thickness of about L=173λ0, which shows the phenomenon of entanglement sudden death43, whereas the magenta downward-pointing triangles are the experimental results of Rn. Because the final state in our experiment can be transformed into a Bell-diagonal form, with a local unitary operation that does not change its entanglement, the analytical expressions of Rn (see Methods) are used to give the theoretical prediction, which is represented by the magenta dotted line. Although the En is larger than the relative Rn at the beginning of evolution, they suffer from sudden death at the same thickness, thereby confirming their self-consistence. We can see that quantum correlation can be smaller or larger than the En during evolution. Specifically, quantum correlation decays exponentially, whereas entanglement disappears completely at the thickness of L>173λ0. This confirms the earlier prediction that quantum discord is more robust against decoherence than entanglement19,20. Because the relative Rn is on an equal footing with other measures of correlations in the form of entropy29, it is not always larger than quantum correlation, as verified by our experimental results. The inset in Fig. 2b further compares non-entanglement quantum correlation defined as D=Q−Rn29 with classical correlation. Purple dots are the experimental results of D, with the purple dotted line representing theoretical prediction. Because of the sudden change in behaviour of Q, the decay rate of D also suffers from sudden changes and we find that D<C.

Another kind of correlation dynamics is shown in Fig. 3, in which the sudden change behaviour disappears. The input state is given by equation (5) with b=0.5 (the separated state, Fig. 3, top panel) and b=1 (the maximally entangled state, Fig. 3, bottom panel). The minimum of S(ρlA) is obtained with θ=45° in Fig. 3 (top panel) and θ=0° in Fig. 3 (bottom panel) (φ=0)23. The green upward-pointing triangles, black squares and red dots represent the experimental results of I, C and Q, respectively. The quantum correlation in Fig. 3 (top panel) remains at 0 and the total correlation is equal to the classical correlation, both of which decay monotonically. Figure 3 (bottom panel) shows another case in which classical correlation remains at 1 and quantum correlation decays exponentially. Compared with the dynamics of entanglement En (blue stars), we find that entanglement also remains at 0, as shown in Fig. 3 (top panel) (experimental results not shown), which is equal to Q there, whereas it is larger than the Q during evolution, as shown in Fig. 3 (bottom panel). Orange diamonds represent the value of Λ (if Λ ≥ 0, it represents the quantity of concurrence44; see Methods), which also decays exponentially. The value of En is set to 0 when Λ<0 according to its definition. The relative Rn (magenta downward-pointing triangles) is also shown in Fig. 3. It remains constant at 0, as shown in Fig. 3 (top panel) (experimental results not shown) and then decays exponentially, as shown in Fig. 3 (bottom panel). Rn completely overlaps with quantum correlation in both cases, and the non-entanglement quantum correlation reads at 0. The experimental results agree well with the corresponding theoretical predictions.

Green upward-pointing triangles, black squares and red dots represent the experimental results of I, C and Q, respectively. The green solid line, black solid line and red dashed line are the corresponding theoretical predictions. En (blue stars) is shown for comparison, with the blue dotted line representing the corresponding theoretical prediction. Orange diamonds represent the experimental results of Λ and the orange dotted line is the theoretical prediction. Λ<0 in a and En is set to 0 (blue stars are not shown). Rn (magenta downward-pointing triangles) is also shown in b, with the magenta dotted line representing the corresponding theoretical prediction, which completely overlaps with quantum correlation. Error bars correspond to counting statistics.

We further show an interesting case in which Q can be larger than C. In this case, the dotted pane is inserted into mode B, as shown in Fig. 1 and the initial input state is given by equation (6). We set b=0.9 and R=0.9 to maximize the value of Q−C. Fig. 4 shows our experimental results. The total correlation (green upward-pointing triangles) decays exponentially, whereas the classical (black squares) and quantum (red dots) correlations exhibit sudden changes in behaviour in their decay rates at about L=78λ0. After this special thickness, the classical correlation remains constant and the quantum correlation decays exponentially with a higher decay rate. During evolution, Q is observed to be larger than C at the thickness interval from about 50λ0 to 90λ0, within the error bars. Such an observation contradicts the early conjecture that C ≥ Q30, and is consistent with previous theoretical predictions23,25,26. The dynamics of entanglement, which are characterized by both En (blue stars) and Rn (magenta downward-pointing triangles), are also shown in Fig. 4. Both characterizations suffer from sudden death at the same thickness of about L=202λ0, and the entanglement is set to 0 in the subsequent evolution. The value of the non-entanglement quantum correlation D (purple dots), which also exhibits a sudden change in the decay rate, is compared with the classical correlation in the inset. We find that entanglement and non-entanglement quantum correlations are always less than the classical correlation in our experiment.

Green upward-pointing triangles, black squares, red dots, blue stars and magenta downward-pointing triangles represent the experimental values of I, C, Q, En and Rn, respectively. The green solid line, black solid line, red dashed line, blue dotted line and magenta dotted line are the corresponding theoretical predictions. The inset (the x axis represents the total thickness of quartz plates and the y axis denotes different kinds of correlations) shows the comparison of D (purple dots) with C. The purple dotted line is the theoretical prediction of D. Error bars correspond to counting statistics.

Discussion

The classical and quantum correlations considered in this experiment are defined by the one-partition measurement of a bipartite system6,7. In such cases, analytical solutions for classical and quantum correlations have been obtained for some kinds of states with a high symmetry18,23,25. Although classical and quantum correlations may be generally asymmetric according to the choice of partition to be measured, for states with maximally mixed marginals, they are symmetric under the interchange of the measured side24. There is also a quantifier of classical correlation with measurement over both partitions of a bipartite system, which is defined as the maximum classical mutual information9,10. For states with maximally mixed marginals, the definitions of classical and quantum correlations are numerically verified to be equal to that defined with one-sided measurement24. A thermodynamic approach is also developed to quantify correlations8,11. In particular, the quantum information deficit is defined to characterize the difference between the information that can be localized with Closed Local Operations and Classical Communications and the total information of the state, and it quantifies the quantumness of correlations11. We find that the quantum-information deficit is equal to quantum discord for Bell-diagonal states. On the basis of the idea that classical states can be measured without disturbance, Luo13 uses the measurement-induced disturbance to characterize classical and quantum correlations. Because of the symmetric property of Bell-diagonal states, these definitions of correlations used in our experiment also coincide with that defined by Luo's method14. Recently, a method to quantify quantum and classical correlations on an equal footing with relative entropy has been proposed14, and it is applicable to multiparticle systems of arbitrary dimensions. In our case, considering the dynamics of Bell-diagonal states, the one-sided definitions of classical and quantum correlations6,7 are consistent with those defined by the equal footing method14. As a result, for the Bell-diagonal states used in our experiment, all of the above separation methods for classical and quantum correlations are coincident.

Through measuring classical and quantum correlations in multipartite systems, Bennett et al.45 recently introduced three postulates that should be satisfied by any measure or indicator of genuine multipartite correlations. They found that the concept of covariance proposed by Kaszlikowski et al.46 to identify the existence of genuine multipartite correlations does not satisfy two postulates, and they concluded that it cannot be an indicator of genuine multipartite classical correlations45. Because the equal footing method mentioned above can be directly applied to multipartite systems with a unified view of quantum and classical correlations14, it may inspire insight into current debates.

The relationship between the En and quantum correlation is also interesting. In our experiment, the En is observed to be even larger than quantum correlation in certain areas of evolution. For bipartite systems, it has also been shown that quantum mutual information considered as the measurement of total correlation can be smaller than the En47,48, which may occur in the case of particles with dimensions larger than five48. Such a contradiction is due to the different frameworks of their definitions. In our case, we can choose the relative Rn to measure entanglement, so as to make it on an equal footing with other measures of correlations in the form of entropy29.

In conclusion, we have shown the sudden change in behaviour in the decay rates of different kinds of correlations in the two-photon system. Our results show that classical and quantum correlations can remain unaffected under certain decoherence areas, which will have important roles in distinguishing correlations23 and designing robust quantum protocols based only on quantum correlation. The early conjecture that C≥Q30 is disproved by our experimental results. On the other hand, classical correlation is always found to be larger than the entanglement and non-entanglement quantum correlation in the experiment.

Methods

Analytical expressions of the En and the relative Rn

For biqubit systems, the En can be given by the analytical formula44

where H(x)=−xlog2x−(1−x)log2(1−x), ϒ is the concurrence given by ϒ=max{0, Λ}, where  and Xj are the eigenvalues in decreasing order of the matrix ρ(σ2⊗σ2)ρ*(σ2⊗σ2), with σ2 denoting the second Pauli matrix and ρ* corresponding to the complex conjugate of ρ in the canonical basis {|HH〉,|HV〉,|VH〉,|VV〉}. In addition, the relative Rn is defined as the minimal distance between ρ and a disentangled state42. For the Bell-diagonal state, if the four eigenvalues of the density matrix are

and Xj are the eigenvalues in decreasing order of the matrix ρ(σ2⊗σ2)ρ*(σ2⊗σ2), with σ2 denoting the second Pauli matrix and ρ* corresponding to the complex conjugate of ρ in the canonical basis {|HH〉,|HV〉,|VH〉,|VV〉}. In addition, the relative Rn is defined as the minimal distance between ρ and a disentangled state42. For the Bell-diagonal state, if the four eigenvalues of the density matrix are  , the relative Rn is given by42

, the relative Rn is given by42

,whereas for any λj≥1/2, we obtain

Additional information

How to cite this article: Li, C.-F. et al. Experimental investigation of classical and quantum correlations under decoherence. Nat. Commun. 1:7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1005 (2010).

References

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Meyer, D. A. Sophisticated quantum search without entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2014–2017 (2000).

Kenigsberg, D., Mor, T. & Ratsaby, G. Quantum advantage without entanglement. Quantum Inf. Comput. 6, 606–615 (2006).

Datta, A., Shaji, A. & Caves, C. M. Quantum discord and the power of one qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 050502 (2008).

Lanyon, B. P., Barbieri, M., Almeida, M. P. & White, A. G. Experimental quantum computing without entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 200501 (2008).

Henderson, L. & Vedral, V. Classical, quantum and total correlations. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 34, 6899–6905 (2001).

Ollivier, H. & Zurek, W. H. Quantum discord: a measure of the quantumness of correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 017901 (2001).

Oppenheim, J., Horodecki, M., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, R. Thermodynamical approach to quantifying quantum correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 180402 (2002).

Terhal, B. M., Horodecki, M., Leung, D. W. & DiVincenzo, D. P. The entanglement of purification. J. Math. Phys. 43, 4286–4298 (2002).

DiVincenzo, D. P., Horodecki, M., Leung, D. W., Smolin, J. A. & Terhal, B. M. Locking classical correlations in quantum states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 067902 (2004).

Horodecki, M. et al. Local versus nonlocal information in quantum-information theory: formalism and phenomena. Phys. Rev. A 71, 062307 (2005).

Groisman, B., Popescu, S. & Winter, A. Quantum, classical, and total amount of correlations in a quantum state. Phys. Rev. A 72, 032317 (2005).

Luo, S. Using measurement-induced disturbance to characterize correlations as classical or quantum. Phys. Rev. A 77, 022301 (2008).

Modi, K., Paterek, T., Son, W., Vedral, V. & Williamson, M. Unified view of quantum and classical correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 080501 (2010).

Zurek, W. H. Quantum discord and Maxwell's demons. Phys. Rev. A 67, 012320 (2003).

Rodríguez-Rosario, C. A., Modi, K., Kuah, A. M., Shaji, A. & Sudarshan, E .C. G. Completely positive maps and classical correlations. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 41, 205301 (2008).

Piani, M., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, R. No-local-broadcasting theorem for multipartite quantum correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 090502 (2008).

Luo, S. Quantum discord for two-qubit systems. Phys. Rev. A 77, 042303 (2008).

Werlang, T., Souza, S., Fanchini, F. F. & Boas, C. J. V. Robustness of quantum discord to sudden death. Phys. Rev. A 80, 024103 (2009).

Ferraro, A., Aolita, L., Cavalcanti, D., Cucchietti, F. M. & Acin, A. Almost all quantum states have non-classical correlations. Preprint at 〈http://arxiv.org/abs/0908.3157v2〉 ( 2009).

Wang, B., Xu, Z. -Y., Chen, Z. -Q. & Feng, M. Non-Markovian effect on the quantum discord. Phys. Rev. A 81, 014101 (2010).

Fanchini, F. F., Werlang, T., Brasil, C. A., Arruda, L. G. E. & Caldeira, A. O. Non-Markovian dynamics of quantum discord. Preprint at 〈http://arxiv.org/abs/0911.1096v3〉 ( 2009).

Maziero, J., Céleri, C. L., Serra, R. M. & Vedral, V. Classical and quantum correlations under decoherence. Phys. Rev. A 80, 044102 (2009).

Maziero, J., Werlang, T., Fanchini, F. F., Céleri, C. L. & Serra, R. M. System-reservoir dynamics of quantum and classical correlations. Phys. Rev. A 81, 022116 (2010).

Sarandy, M. S. Classical correlation and quantum discord in critical systems. Phys. Rev. A 80, 022108 (2009).

Luo, S. & Zhang, Q. Observable correlations in two-qubit states. J. Stat. Phys. 136, 165–177 (2009).

Schumacher, B. & Westmoreland, M. D. Quantum mutual information and the one-time pad. Phys. Rev. A 74, 042305 (2006).

Vedral, V. The role of relative entropy in quantum information theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 197–234 (2002).

Vedral, V. The elusive source of quantum effectiveness. Preprint at 〈http://arxiv.org/abs/0906.3656v1〉 (2009).

Lindblad, G. Quantum entropy and quantum measurement. In Quantum Aspects of Optical Communications. Lecture Notes in Physics Vol 378 (eds. Bendjaballah, C., et al.) 71–80 (Springer, 1991).

Preskill, J. Lecture notes quantum information and computation, http://www.theory.caltech.edu/people/preskill/ph229/notes/chap3.pdf (1998).

Kwiat, P. G., Berglund, A. J., Altepeter, J. B. & White, A. G. Experimental verification of decoherence-free subspaces. Science 290, 498–501 (2000).

Xu, J. -S. et al. Experimental demonstration of photonic entanglement collapse and revival. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 100502 (2010).

Hamieh, S., Kobes, R. & Zaraket, H. Positive-operator-valued measure optimization of classical correlations. Phys. Rev. A 70, 052325 (2004).

Berglund, A. J. Quantum coherence and control in one- and two-photon optical systems. Preprint at 〈http://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0010001v2〉 ( 2000).

Kwiat, P. G., Waks, E., White, A. G., Appelbaum, I. & Eberhard, P. H. Ultrabright source of polarization-entangled photons. Phys. Rev. A 60, R773–R776 (1999).

Puentes, G., Voigt, D., Aiello, A. & Woerdman, J. P. Tunable spatial decoherers for polarization-entangled photons. Opt. Lett. 31, 2057–2059 (2006).

Aiello, A., Puentes, G., Voigt, D. & Woerdman, J. P. Maximally entangled mixed-state generation via local operations. Phys. Rev. A 75, 062118 (2007).

James, D. F. V., Kwiat, P. G., Munro, W. J. & White, A. G. Measurement of qubits. Phys. Rev. A 64, 052312 (2001).

Mazzola, L., Piilo, J. & Maniscalco, S. Sudden transition between classical and quantum decoherence. Preprint at 〈http://arxiv.org/abs/1001.5441v2〉 ( 2010).

Bennett, C. H., DiVincenzo, D. P., Smolin, J. A. & Wootters, W. K. Mixed-state entanglement and quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. A 54, 3824–3851 (1996).

Vedral, V., Plenio, M. B., Rippin, M. A. & Knight, P. L. Quantifying entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 2275–2279 (1997).

Yu, T. & Eberly, J. H. Sudden death of entanglement. Science 323, 598–601 (2009).

Wootters, W. K. Entanglement of formation of an arbitrary state of two qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 2245–2248 (1998).

Bennett, C. H., Grudka, A., Horodecki, M., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, R. Postulates for measures of genuine multipartite correlations. Preprint at 〈http://arxiv.org/abs/0805.3060v2〉 ( 2010).

Kaszlikowski, D., Sen(De), A., Sen, U., Vedral, V. & Winter, A. Quantum correlation without classical correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 070502 (2008).

Hayden, P., Leung, D. W. & Winter, A. Aspects of generic entanglement. Commun. Math. Phys. 265, 95–117 (2006).

Li, N. & Luo, S. Total versus quantum correlations in quantum states. Phys. Rev. A 76, 032327 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank V. Vedral, S. Luo and Y.-C. Wu for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Fundamental Research Program, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 60121503, 10874162).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.F.L. and J.S.X. designed the experiment. J.S.X. and X.Y.X. performed the experiment. J.S.X. analysed the theoretical prediction and experimental data. C.J.Z., X.B.Z. and G.C.G. contributed to the theoretical analysis. J.S.X. and C.F.L. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, JS., Xu, XY., Li, CF. et al. Experimental investigation of classical and quantum correlations under decoherence. Nat Commun 1, 7 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1005

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1005

This article is cited by

-

Visualizing sudden transition of decoherence via quantum steering ellipsoid

Applied Physics B (2024)

-

Dynamics of multipartite quantum steering for different types of decoherence channels

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Quantum information transfer using weak measurements and any non-product resource state

Quantum Information Processing (2022)

-

Quantifying of Quantum Correlations in an Optomechanical System with Cross-Kerr Interaction

Journal of Russian Laser Research (2022)

-

Method for generating randomly perturbed density operators subject to different sets of constraints

Quantum Information Processing (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.