Abstract

The Jurassic (∼201–145 Myr ago) was long considered a warm ‘greenhouse’ period; more recently cool, even ‘icehouse’ episodes have been postulated. However, the mechanisms governing transition between so-called Warm Modes and Cool Modes are poorly known. Here we present a new large high-quality oxygen-isotope dataset from an interval that includes previously suggested mode transitions. Our results show an especially abrupt earliest Middle Jurassic (∼174 Ma) mid-latitude cooling of seawater by as much as 10 °C in the north–south Laurasian Seaway, a marine passage that connected the equatorial Tethys Ocean to the Boreal Sea. Coincidence in timing with large-scale regional lithospheric updoming of the North Sea region is striking, and we hypothesize that northward oceanic heat transport was impeded by uplift, triggering Cool Mode conditions more widely. This extreme climate-mode transition provides a counter-example to other Mesozoic transitions linked to quantitative change in atmospheric greenhouse gas content.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cold and warm climate ‘modes’ in the Jurassic have been suggested1 on the basis of palaeobiogeographic and oxygen isotopic evidence2,3. In support of cold modes, several authors have noted the occurrence of glendonite (predominantly cold-water calcite pseudomorphs) and ice-rafted debris in circum-Arctic basins4,5,6, although whether significant continental ice sheets developed during the Jurassic is debatable7. In contrast, the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (T-OAE) in the Early Jurassic (∼182 Ma) stands out as a very warm episode8,9. The origins of such warm interludes are well investigated10,11, but the character and origins of the cold periods in the Jurassic are not understood.

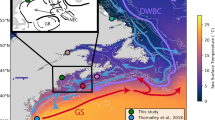

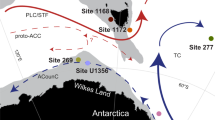

The area of western Europe was situated between palaeolatitudes 30–45° N (ref. 12). Much of the region was traversed by epicontinental seas forming the so-called ‘Laurasian’ Seaway that connected the low-palaeolatitude Tethys Ocean in the south to the high-palaeolatitude Boreal Sea via the Viking Corridor in the north (Fig. 1), and some authors have suggested that seaway dynamics had wide effects on palaeoceanography and climate13.

(a) Map shows the connection between the equatorial Tethys Ocean and the Boreal Sea via the Laurasian Seaway; the latter including the Viking Corridor which was several hundred kilometres wide43. Red arrows mark generalized palaeocurrents (see text, ref. 44, and references therein). (b) Detail of Laurasian Seaway palaeogeography with the region affected by North Sea Dome as determined by the generalized outer limit of the Toarcian subcrop40. Brown arrows represent the siliciclastic sediment supply/transport in relation to domal uplift39,40. Sample locations are numbered and identified by stars (Hebrides Basin (I; Scotland), Cleveland Basin (II; England), Swabo-Franconian Basin (III; Germany) and Lusitanian (IV; Portugal)/Basque-Cantabrian basins (V; Spain)). SNS, Southern North Sea Basin, W, Wessex Basin. Figures modified from refs 12, 45, 44 and references therein.

Here, we present new data comprising oxygen-isotope ratios from well-preserved late Pliensbachian to Bajocian (191–168 Ma) calcite macrofossils of the Laurasian Seaway area, which we use to reconstruct past seawater temperatures. The new data set is unprecedented in terms of degree of detail and stratigraphic precision for this interval of time. Diagenetically resistant low-Mg-calcite fossils (belemnites, bivalves and brachiopods) were screened for post-depositional alteration and only those samples lacking physical or chemical signs of alteration were regarded as preserving the original carbonate δ18O (Methods section), following the detailed explanations recently fully reviewed in ref. 14. We infer an abrupt earliest Middle Jurassic (∼174 Ma), mid-latitude, cooling of seawater by as much as 10 °C, and we conclude that tectonic influence on seaway connectivity had far-reaching effects on palaeoclimate.

Results

Oxygen isotopes

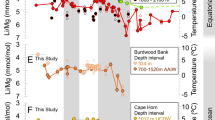

Large oxygen-isotope fluctuations occur over the studied interval (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data 1), highlighting the Late Pliensbachian Cool Event15,16, the warm episode during the T-OAE (refs 9, 17), and the Middle Jurassic cold interval18,19 earlier described as a long-term trend to cooler temperatures7. Here we show for the first time that this latter positive δ18O shift is very sharp and occurs precisely in the earliest Aalenian just after the Early to Middle Jurassic boundary (Toarcian–Aalenian; Fig. 2).

Data obtained from pristine and biostratigraphically well-constrained marine calcite fossils from selected European basins (Methods section, Supplementary Data 1, Supplementary Table 1). Shading behind the oxygen-isotope data highlight warm (red) and cool (blue) palaeotemperatures. Plot symbol shape indicates macrofossil type and colour indicates locality. The plot highlights the abrupt and large magnitude shift towards cold seawater temperatures in the earliest Middle Jurassic which, in Hebrides Basin, represents at least 10 °C (Fig. 3). The Late Pliensbachian Cold Event and the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic (hot) Event are also represented. Superimposed higher frequency climate changes are present during the complete time span for all localities. Data ranges for specific times reflect expected (annual) temperature changes16,27 and habitat effects28.

In the Hebrides Basin the shift to heavier values is >2.5‰ (Fig. 3). Both positive and negative isotopic trends in the data set are the same for the different basins and provinces with the largest amplitudes recorded in the Cleveland and Hebrides basins, smaller amplitudes in the Swabo-Franconian Basin, and smallest amplitudes in the Lusitanian and Basque-Cantabrian basins (Fig. 2). The new data set also shows that the negative oxygen-isotope excursion during the T-OAE is transient and superimposed on an overall warming trend through the entire Toarcian in the Cleveland Basin. The Toarcian data from the Hebrides are especially significant as they confirm equivalently warm temperatures in both the Hebrides and Cleveland basins during the Toarcian. Thus the early Aalenian presents one of the most pronounced δ18O inclines observed for Phanerozoic data sets. The resulting heavy values persist during the Aalenian and at least the early Bajocian (that is, for >∼5 Myr), with some significant short-term returns to warm conditions (for example, in the humphresianum zone: biosubzone no. 72; Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

Lithology, stratigraphy and transgressive/regressive (T/R) phases are from refs 25, 54, 76. Intervals lacking well-preserved ammonite fossils are indicated by grey shading and so denote limited age uncertainty. Shading in the graphic log denotes darker lithology. Transgressive/regressive phases denoted T/R. Shading behind the oxygen-isotope data highlight warm (red) and cool (blue) palaeotemperatures. The oxygen-isotope values increase abruptly in the murchisonae zone and at that time the unconformity was at maximum extent35,36. Note that this increase in the oxygen-isotope values occurs with a clear facies change from deeper to shallower water. There is a hint of other small palaeotemperature changes in conjunction with T/R cycles, but the magnitude of the T/R cycles and the palaeotemperature changes is small in comparison to the change across the Early/Middle Jurassic transition with perhaps the exception of the humprhresianum zone.

Carbon isotopes

Carbon-isotope data (Supplementary Data 1) generated from the same sample set do not show a marked change at the Toarcian–Aalenian transition, but instead show a long-term decline in values across the same time span as oxygen isotope become substantially heavier (Supplementary Figs 1 and 2).

Discussion

Taxa analysed for this study were selected on the basis of lack of observed vital effects on oxygen-isotope ratios in biogenic calcite of modern representatives16,20. Changes in the oxygen isotopic composition of calcite shells might also partly reflect changes in seawater δ18O or pH2. However, given the ubiquitous normal marine salinities evident from the studied fossil assemblages, neither factor can have had a significant influence on shell δ18O. Only for the T-OAE, characterized in the seaway by up to 10 m of laminated black shale, has it been suggested that Laurasian Seaway salinity deviated from the long-term mean, in this case by influx of freshwater21,22. The 2.5‰ δ18O increase in the early Aalenian might alternatively be explained by evaporative concentration of the heavy isotope of oxygen, but that would imply hypersalinity when fossil and sedimentological evidence demonstrate stenohaline conditions through the whole late Toarcian to early Aalenian interval23,24,25.

We therefore conclude that the observed strong shift towards heavy δ18O values in the early Aalenian principally reflects seawater temperature change, indicating about 10 °C of cooling over a period of about 0.5 Myr, and lowest temperatures of ∼4 °C using the standard assumption26 of −1‰ (Standard Mean Ocean Water) for seawater δ18O (Fig. 2). Some calcite macrofossil taxa stopped calcification in cool seasons, suggesting that the new data set might not record the coldest cold-season water temperatures, and that warm season temperatures in these climatic regions are overrepresented27. Such a mechanism may explain also the lower variability of δ18O in the Hebrides Basin relative to the Cleveland Basin (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 1, and ref. 28). Lighter oxygen-isotope values and more variability are evident from the northerly Hebrides and Cleveland basins relative to the records from the Lusitanian and Basque-Cantabrian basins; this likely results from shallower water habitats in northerly basins (∼100 versus ∼200 m)13,29 and a latitudinal salinity effect of about ∼1 per mil (cf. ref. 30).

The same late Pliensbachian to Bajocian palaeoclimatic fluctuations have also been suggested for the Arctic region, based principally on mineralogical, palaeontological and sedimentological data. Significant cooling has been inferred for the late Pliensbachian and the earliest Middle Jurassic (including the Aalenian and Bajocian) based on glendonite occurrence, ice-rafted debris, and low marine diversity, as well as palynology; in contrast, a temperature maximum in the early Toarcian is evidenced by palynological data indicative of northward expansion of terrestrial floras4,31,32,33.

Over the studied interval there is no clear correlation between the oxygen isotope and carbon-isotope records (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore an explanation for the palaeotemperature changes based on inferred marine organic carbon burial is not supported by the data. In addition, positive carbon-isotope excursions for latest Toarcian to Bajocian successions of other regions in the Laurasian Seaway18,19,34,35,36,37 are different in timing and magnitude19, and have been related to more local enhanced biological activity of eutrophic phytoplankton and radiolarians which strengthened the biological pump36.

We hypothesize that the uplift of the North Sea Dome, caused by a rising asthenospheric plume38,39,40, led to obstruction of a northward flowing current through the Viking Corridor and thus strongly reduced heat transport to the Arctic regions (Fig. 1). At the same time, cold Arctic waters were able to exert influence on marine palaeotemperatures at palaeolatitudes as low as 45° reaching at least the Hebrides Basin (Figs 1 and 2). A comparable scenario is the Cenozoic domal uplift of the Greenland–Scotland Ridge which regulated the flow of warm water into the North Atlantic41,42. In the Jurassic North Sea area regional uplift affected a zone of ∼1,250 km in diameter38,39,40. Timing of the uplift has been identified by reference to the early Aalenian unconformity, widely observed in seismic reflection and borehole data39,40. In addition, latest Toarcian and earliest Aalenian shoreline regression is indicated by sedimentary facies changes in the Cleveland Basin (Yorkshire), Wessex Basin (Dorset) and other North Sea perimetric basins, further indicating regional tectonic uplift38,39,40. Pronounced provincialism in ammonite faunas observed for both the Laurasian Seaway and Arctic regions43 initiated in the early Aalenian confirms a structural barrier between low and high latitudes33,43.

North Sea Dome uplift would have fundamentally modified palaeocean current patterns. The general Early Jurassic ocean circulation of the NW Tethys and adjacent shelf is thought to have been characterized by a gyre acting down to water depths of several hundred metres, perhaps modified by monsoonal processes (ref. 44 and references therein). The Jurassic palaeogeographic/palaeoceanic setting was similar to the modern North Atlantic Gulf Stream or North Pacific Kuroshio current with a general northward surface flow between ∼ 35 and 60°N (Fig. 1), although clearly it would be inappropriate to take the parallels between modern open ocean currents and their Jurassic seaway counterparts too far.

Early Jurassic ammonite distributions in the Laurasian Seaway show progressive homogenization of faunas from the latest Pliensbachian to early Toarcian, and re-establishment of distinct faunal provinces in the later Toarcian45, supporting earlier conclusions based on a wider range of invertebrate fossils evidencing northward faunal spread in the early Toarcian32,46,47,48,49,50. A strong northward flow in the Viking Corridor is also suggested for the later Middle Jurassic by invertebrate fossil distributions for times when the strait is known to have been open43. In contrast, southward current flow was suggested for the Toarcian based on model calculations13; a finding difficult to reconcile with both the stenohaline fossil distributions and associated oxygen-isotope data9,28,46,48,50 (Supplementary Fig. 1), all showing relatively warm waters in the Toarcian Laurasian Seaway. Directionality apart, the models are of particular value in that they emphasise the potential significance of the seaway for heat transport.

The mechanism suggested here for the transition from Toarcian Warm Mode to Aalenian-Bajocian Cool Mode may also have been responsible for the transition from an earlier Pliensbachian Warm Mode to a later Pliensbachian Cool Mode. The possibility of an early onset of North Sea doming is suggested by the occurrence of regressive facies in the late Pliensbachian of the North Sea region, similar to those of the late Toarcian51,52; namely the Drake Formation (Southern North Sea Basin), Scalpa Sand Formation (Hebrides Basin), Staithes Sand (Cleveland Basin), Downcliff Sand and Thorncombe Sand (Wessex Basin). A global sea-level rise of likely tectonic origin, with a weakly quantified magnitude in the order of up to 100 m, has been well documented for the early Toarcian53; thus any seaway bathymetric (that is, regional) effect from an early, Pliensbachian, North Sea domal uplift is likely to have been counteracted by eustasy, at least until the late Toarcian.

The Early to Middle Jurassic scenario elaborated here shows clearly that major modifications in Mesozoic oceanic current patterns have significant influence on large magnitude, abrupt climate change and potentially govern transformations between Warm/Cool climate modes. Although greenhouse gases may also have had strong influence on Mesozoic events, the T-OAE being a prime example, this is not necessarily the case for other highly significant transitions. The North Sea Dome triggered perhaps the largest palaeoceanographically induced climate change in the Jurassic, at least on a super-regional scale.

Methods

Sampling

Belemnites, ostreoids, pectinids, pinnids and brachiopods were collected in Yorkshire, NE England (Robin Hood’s Bay–Hawsker Bottoms, Saltwick Nab, Ravenscar–BleaWyke, Staithes–Brackenberry Wyke and Hundale Point) and in the Inner Hebrides, Scotland (Bearerraig on the Isle of Skye and Druim an Aonaich on the Isle of Raasay; Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Table 2). Samples from the South German Swabo-Franconian Basin originate mainly from the Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart. A few additional samples from this basin were taken in the Aubach valley near Aselfingen in the Wutach area. The samples cover in total the stratigraphic interval from the davoei (late early Pliensbachian) to the humphriesianum (late early Bajocian) ammonite biozones (Supplementary Table 1). Previously published data (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data 1) were added to the new data for several localities (Bearreraig54; Robin Hood's Bay, Castle Chamber, Staithes and Brackenberry Wyke16; Hawsker Bottoms, Saltwick Bay, Ravenscar and Blea Wyke28,55,56,57), and for coevally deposited successions of Scotland (Inverarish Burn and Beinn na Leac18), South Germany (Roadcut, D (ref. 54)), Portugal (Lusitanian Basin, Peniche29 and Cabo Mondego54) and Spain (Basque-Cantabrian Basin, Camino58,59, Santiurde de Reinosa58,59, San Andrés58,59 and Fuentelsaz60, the latter including the Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the Aalenian Stage). Only literature data from stratigraphically well-defined and diagenetically well-screened samples were used for the plots and discussions to maintain the comparability to our new stratigraphically well-defined, well-screened and carefully selected samples, representing best preserved material available.

Stratigraphy

All sections sampled are biostratigraphically very well-constrained by ammonite biozonation, in many cases being amongst the most intensively investigated in the world, and the detailed subdivision is given in refs 25, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65. In the Bearreraig section (Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 1) no biostratigraphically significant taxa occur between 62 and 85.8 m. It was therefore necessary to approximate the base of the ovalis and laeviuscula zones and the sayni, trigonalis and laeviuscula subzones (Supplementary Data 1). Higher in the section we approximated the base of the sauzei zone (Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 1) at the highest level of the major erosion surface about 8–10 m below the top of Holm Sandstone. Zonal and subzonal boundaries from the murchisonae zone are based on heights below a prominent belemnite-rich bed (=marker bed O16, cf. ref. 25). We use the height of 19.65 m for the base of the gigantea subzone and 70.00 m for the base of the ovalis subzone (ref. 25).

Selection

Belemnites, bivalves and brachiopods were chosen as substrates for analysis. The fossils could usually not be determined to finer taxonomic levels because generally only small fragments were available for collection (Supplementary Data 1); delineation of large-magnitude oxygen-isotope variations, however, is possible even with taxonomically undetermined specimens2,16.

Screening and geochemical measurement

Despite their resistance to diagenesis, fossil specimens were carefully screened to identify potential post-depositional alteration which might have reset the primary geochemical signal2,14,66. Bivalve and brachiopod shells were prepared, optically inspected and hand-picked using a binocular microscope and needle16,67. For belemnites, fresh surfaces of broken pieces were inspected under the binocular microscope, and powders were drilled from the best material with a handheld microdrill16,66. Representative shell splinters of processed bivalves and brachiopods, and fragments of most of the belemnite rostra were additionally screened for preservation of the ultrastructure using a FEI Quanta 250 scanning electron microscope (Geological Museum in Copenhagen). Only shells with smooth surfaces (for example, lamellar or fibrous) and no signs of re-crystallization were classified as pristine67,68. Aliquots of 300–700 μg (Copenhagen) and 150–300 μg (Innsbruck) were reacted in sealed glass vials by adding anhydrous phosphoric acid after removal of atmospheric contaminants with He. Resultant carbon dioxide was analysed for oxygen- and carbon-isotope ratios at the Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, University of Copenhagen (Iso Prime triple collector Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer) and at the Institut für Geologie und Paläontologie, University of Innsbruck (ThermoFinnigan DeltaplusXL mass spectrometer; Supplementary Data 1). The reproducibility of the measurements determined by the s.d. of in-house reference materials was 0.18‰ for δ18O and 0.08‰ for δ13C (2 s.d., n=649; ref. 66) in Copenhagen, and better than 0.2‰ (2 s.d.) for δ18O and δ13C in Innsbruck. Temperatures calculated from the oxygen-isotope values (Fig. 2) are based on ref. 69 assuming a δ18O value of −1‰ SMOW for ambient water. The Mn/Ca and Sr/Ca ratios for all processed calcite fossils (Supplementary Data 1) were quantified using the Perkin Elmer Optima 7000 DV ICP-OES at the University of Copenhagen using aliquots from the H3PO4 treatment remaining after the stable isotope analyses66. Reproducibility for Mn/Ca and Sr/Ca ratios, assessed by using different reference materials, was better than 2.8% (2 s.d.) and 2.5% (2 s.d.), respectively (for further details see ref. 66). Mn enrichment and Sr depletion in biogenic calcite were used to identify alteration in samples2,67. Mn and Sr concentrations in seawater vary temporarily, spatially and, in addition, Sr incorporation in biogenic calcite is variable between taxa and controlled by environmental factors16,57,66,70,71,72,73,74,75. Such potential primary Mn/Ca enrichments and primary variability of Sr/Ca ratios in calcite fossils2,16,57 were taken into account (Supplementary Data 1, and ref. 14).

Additional information

How to cite this article: Korte, C. et al. Jurassic climate mode governed by ocean gateway. Nat. Commun. 6:10015 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10015 (2015).

References

Frakes, L. A., Francis, J. E. & Syktus, J. I. Climate Modes of the Phanerozoic: The History Of Earth’s Climate Over The Past 600 Million Years Cambridge University Press (1992).

Veizer, J. et al. 87Sr/86Sr, δ13C and δ18O evolution of Phanerozoic seawater. Chem. Geol. 161, 59–88 (1999).

Dromart, G. et al. Ice age at the Middle-Late Jurassic transition? Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 213, 205–220 (2003).

Kaplan, M. E. Calcite pseudomorphoses from the Jurassic and lower Cretaceous deposits of northern East Siberia. Sov. Geol. Geophys. 12, 62–70 (1978).

Price, G. D. The evidence and implications of polar ice during the Mesozoic. Earth-Sci. Rev. 48, 183–210 (1999).

Rogov, M. A. & Zakharov, V. A. Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous glendonite occurrences and their implication for Arctic paleoclimate Reconstructions and Stratigraphy. Earth Sci. Front. 17, 345–347 (2010).

Dera, G. et al. Climatic ups and downs in a disturbed Jurassic world. Geology 39, 215–218 (2011).

Jenkyns, H. C. The Early Toarcian (Jurassic) Anoxic Event: stratigraphic, sedimentary, and geochemical evidence. Am. J. Sci. 288, 101–151 (1988).

Bailey, T. R., Rosenthal, Y., McArthur, J. M., van de Schootbrugge, B. & Thirlwall, M. F. Paleoceanographic changes of the Late Pliensbachian–Early Toarcian interval: a possible link to the genesis of an Oceanic Anoxic Event. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 212, 307–320 (2003).

Hesselbo, S. P. et al. Massive dissociation of gas hydrate during a Jurassic oceanic anoxic event. Nature 406, 392–395 (2000).

Jenkyns, H. C. Geochemistry of oceanic anoxic events. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 11, Q03004 (2010).

Coward, M. P., Dewey, J. F., Hempton, M. & Holroyd, J. in The Millennium Atlas: Petroleum Geology Of The Central And Northern North Sea eds Evans D., Graham C., Armour A., Bathurst P. 17–33Geological Society Publishing House (2003).

Bjerrum, C. J., Surlyk, F., Callomon, J. H. & Slingerland, R. L. Numerical paleoceanographic study of the Early Jurassic transcontinental Laurasian Seaway. Paleoceanography 16, 390–404 (2001).

Ullmann, C. V. & Korte, C. Diagenetic alteration in low-Mg calcite from macrofossils: a review. Geol. Q. 59, 3–20 (2015).

van de Schootbrugge, B. et al. Early Jurassic climate change and the radiation of organic-walled phytoplankton in the Tethys Ocean. Paleobiology 31, 73–97 (2005).

Korte, C. & Hesselbo, S. P. Shallow marine carbon and oxygen isotope and elemental records indicate icehouse–greenhouse cycles during the Early Jurassic. Paleoceanography 26, PA4219 (2011).

Rosales, I., Robles, S. & Quesada, S. Elemental and oxygen isotope composition of Early Jurassic belemnites: salinity vs. temperature signals. J. Sediment. Res. 74, 342–354 (2004).

Gómez, J. J., Canales, M. L., Ureta, S. & Goy, A. Palaeoclimatic and biotic changes during the Aalenian (Middle Jurassic) at the southern Laurasian Seaway (Basque–Cantabrian Basin, northern Spain). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 275, 14–27 (2009).

Price, G. D. Carbon-isotope stratigraphy and temperature change during the Early–Middle Jurassic (Toarcian–Aalenian), Raasay, Scotland, UK. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 285, 255–263 (2010).

Wefer, G. & Berger, W. H. Isotope paleontology: growth and composition of extant calcareous species. Mar. Geol. 100, 207–248 (1991).

Sælen, G., Doyle, P. & Talbot, M. R. Stable-isotope analyses of belemnite rostra from the Whitby Mudstone Formation, England: surface water conditions during deposition of a marine black shale. Palaios 11, 97–117 (1996).

McArthur, J. M., Algeo, T. J., van de Schootbrugge, B., Li, Q. & Howarth, R. J. Basinal restriction, black shales, Re-Os dating, and the Early Toarcian (Jurassic) oceanic anoxic event. Paleoceanography 23, PA4217 (2008).

Knox, R. W. O’B. Lithostratigraphy and depositional history of the late Toarcian sequence at Ravenscar, Yorkshire. Proc. Yorks. Geol. Soc. 45, 99–108 (1984).

Riding, J. B. A palynological investigation of Toarcian early Aalenian strata from the Blea Wyke area, Ravenscar, North Yorkshire. Proc. Yorks. Geol. Soc. 45, 109–122 (1984).

Morton, N. & Hudson, J. D. in Field geology of the British Jurassic ed. Taylor P. D. 209–280 (1995).

Lhomme, N., Clarke, G. K. C. & Ritz, C. Global budget of water isotopes inferred from polar ice sheets. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L20502 (2005).

Ullmann, C. V., Wiechert, U. & Korte, C. Oxygen isotope fluctuations in a modern North Sea oyster (Crassostrea gigas) compared with annual variations in seawater temperature: implications for palaeoclimate studies. Chem. Geol. 277, 160–166 (2010).

Ullmann, C. V., Thibault, N., Ruhl, M., Hesselbo, S. P. & Korte, C. Effect of a Jurassic oceanic anoxic event on belemnite ecology and evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10073–10076 (2014).

Suan, G., Mattioli, E., Pittet, B., Mailliot, S. & Lécuyer, C. Evidence for major environmental perturbation prior to and during the Toarcian (Early Jurassic) oceanic anoxic event from the Lusitanian Basin, Portugal. Paleoceanography 23, PA1202 (2008).

LeGrande, A. N. & Schmidt, G. A. Global gridded data set of the oxygen isotopic composition in seawater. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L12604 (2006).

Ilyina, V. I. Subdivision and correlation of the marine and non-marine Jurassic sediments in Siberia based on palynological evidence. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 48, 357–364 (1986).

Zakharov, V. A., Shurygin, B. N., Il’ina, V. I. & Nikitenko, B. L. Pliensbachian–Toarcian biotic turnover in north Siberia and the Arctic region. Stratigr. Geol. Correl. 14, 399–417 (2006).

Meledina, S. V., Shurygin, B. N. & Dzyuba, O. S. Stages in development of mollusks, paleobiogeography of boreal seas in the Early-Middle Jurassic and zonal scales of Siberia. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 46, 239–255 (2005).

Bartolini, A., Baumgartner, P. O. & Guex, J. Middle and Late Jurassic radiolarian palaeoecology versus carbon-isotope stratigraphy. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 145, 43–60 (1999).

Morettini, E. et al. Carbon isotope stratigraphy and carbonate production during the Early–Middle Jurassic: examples from the Umbria–Marche–Sabina Apennines (central Italy). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 184, 251–273 (2002).

Sandoval, J. et al. Aalenian carbon-isotope stratigraphy: calibration with ammonite, radiolarian and nannofossil events in the Western Tethys. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 267, 115–137 (2008).

Hesselbo, S. P. et al. Carbon-cycle perturbation in the Middle Jurassic and accompanying changes in the terrestrial paleoenvironment. J. Geol. 111, 259–276 (2003).

Hallam, A. & Sellwood, B. W. Middle Mesozoic sedimentation in relation to tectonics in the British area. J. Geol. 84, 301–321 (1976).

Underhill, J. R. & Partington, M. A. Jurassic thermal doming and deflation in the North Sea: implications of the sequence stratigraphic evidence. Petrol. Geol. Conf. Ser. 4, 337–345 (1993).

Underhill, J. R. & Partington, M. A. in Siliciclastic Sequence Stratigraphy: Recent Developments and Applications eds Weimer P., Posamentier H. W. 58, 449–484AAPG Memoirs (1994).

Wright, J. D. & Miller, K. G. Control of North Atlantic deep water circulation by the Greenland-Scotland ridge. Paleoceanography 11, 157–170 (1996).

Poore, H., White, N. & Maclennan, J. Ocean circulation and mantle melting controlled by radial flow of hot pulses in the Iceland plume. Nat. Geosci. 4, 558–561 (2011).

Callomon, J. H. The Middle Jurassic of western and northern Europe: its subdivisions, geochronology and correlations. Geol. Surv. Den. Greenl. Bull. 1, 61–73 (2003).

Damborenea, S. E., Echevarría, J. & Ros-Franch, S. Southern Hemisphere Palaeobiogeography of Triassic-Jurassic Marine Bivalves Springer (2013).

Dera, G., Neige, P., Dommergues, J.-L. & Brayard, A. Ammonite paleobiogeography during the Pliensbachian–Toarcian crisis (Early Jurassic) reflecting paleoclimate, eustasy, and extinctions. Glob. Planet. Change 78, 92–105 (2011).

Kiessling, W. & Flügel, E. in Phanerozoic Reef Patterns eds Kiessling W., Flügel E., Golonka J. 72, 77–92SEPM Special Publication (2002).

Macchioni, F. & Cecca, F. Biodiversity and biogeography of middle–late Liassic ammonoids: implications for the early Toarcian mass extinction. Geobios 35, (suppl. 1): 165–175 (2002).

Schweigert, G. On the occurrence of the Tethyan ammonite genus Meneghiniceras (Phylloceratina: Juraphyllitidae) in the Upper Pliensbachian of SW Germany. Stuttg. Beitr. Naturk. Ser. B 356, 1–15 (2005).

Nikitenko, B. L. The Early Jurassic to Aalenian paleobiogeography of the Arctic Realm: implication of microbenthos (Foraminifers and Ostracodes). Stratigr. Geol. Correl. 16, 59–80 (2008).

Bourillot, R., Neige, P., Pierre, A. & Durlet, C. Early-Middle Jurassic lytoceratid ammonites with constrictions from Morocco: palaeobiogeographical and evolutionary implications. Palaeontology 51, 597–609 (2008).

Husmo, T. et al. in The Millennium Atlas: Petroleum Geology of the Central and Northern North Sea eds Evans D., Graham C., Armour A., Bathurst P. 129–155Geological Society Publishing House (2003).

Hesselbo, S. P. & Jenkyns, H. C. in Mesozoic and Cenozoic Sequence Stratigraphy of European Basins, SEPM Special Publication Vol. 60, eds de Graciansky P.-C.et al. 561–581Society for Sedimentary Geology (1998).

Hallam, A. Estimates of the amount and rate of sea-level change across the Rhaetian–Hettangian and Pliensbachian–Toarcian boundaries (latest Triassic to early Jurassic). J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 154, 773–779 (1997).

Jenkyns, H. C., Jones, C. E., Gröcke, D. R., Hesselbo, S. P. & Parkinson, D. N. Chemostratigraphy of the Jurassic System: applications, limitations and implications for palaeoceanography. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 159, 351–378 (2002).

McArthur, J. M., Donovan, D. T., Thirlwall, M. F., Fouke, B. W. & Mattey, D. Strontium isotope profile of the early Toarcian (Jurassic) oceanic anoxic event, the duration of ammonite biozones, and belemnite palaeotemperatures. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 179, 269–285 (2000).

Li, Q., McArthur, J. M. & Atkinson, T. C. Lower Jurassic belemnites as indicators of palaeo-temperature. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 315–316, 38–45 (2012).

Ullmann, C. V., Hesselbo, S. P. & Korte, C. Tectonic forcing of Early to Middle Jurassic seawater Sr/Ca. Geology 41, 1211–1214 (2013).

Rosales, I., Quesada, S. & Robles, S. Primary and diagenetic isotopic signals in fossils and hemipelagic carbonates: the Lower Jurassic of northern Spain. Sedimentology 48, 1149–1169 (2001).

Rosales, I., Quesada, S. & Robles, S. Paleotemperature variations of Early Jurassic seawater recorded in geochemical trends of belemnites from the Basque-Cantabrian basin, northern Spain. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 203, 253–275 (2004).

Cresta, S. et al. The Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) of the Toarcian-Aalenian Boundary (Lower-Middle Jurassic). Episodes 24, 166–175 (2001).

Gowland, S. & Riding, J. B. Stratigraphy, sedimentology and palaeontology of the Scarborough Formation (Middle Jurassic) at Hundale Point, North Yorkshire. Proc. Yorks. Geol. Soc. 48, 375–392 (1991).

Hesselbo, S. P. & Jenkyns, H. C. in Field Geology of the British Jurassic ed. Taylor P. D. 105–150 (1995).

Schlatter, R. in DUGW-Stratigraphische Kommission – Subkommission für Jura-Stratigraphie, Jahrestagung 1997 in Blumberg-Achdorf, Wutachtal (7.5.-10.5.1997), Exkursionsführer eds Bloos G., Dietl G., Schlatter R., Schweigert G., Urlichs M. 13–19 (1997).

Urlichs, M. in DUGW-Stratigraphische Kommission – Subkommission für Jura-Stratigraphie, Jahrestagung 1997 in Blumberg-Achdorf, Wutachtal (7.5.-10.5.1997), Exkursionsführer eds Bloos G., Dietl G., Schlatter R., Schweigert G., Urlichs M. 20–30 (1997).

Howarth, M. K. The Lower Lias of Robin Hood’s Bay, Yorkshire, and the work of Leslie Bairstow. Bull. Nat. Hist. Mus. Geol. 58, 81–152 (2002).

Ullmann, C. V. et al. Partial diagenetic overprint of Late Jurassic belemnites from New Zealand: Implications for the preservation potential of δ7 Li values in calcite fossils. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 120, 80–96 (2013).

Korte, C., Kozur, H. W., Bruckschen, P. & Veizer, J. Strontium isotope evolution of Late Permian and Triassic seawater. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 47–62 (2003).

Cochran, J. K. et al. Effect of diagenesis on the Sr, O, and C isotope composition of late Cretaceous mollusks from the Western Interior Seaway of North America. Am. J. Sci. 310, 69–88 (2010).

O’Neil, J. R., Clayton, R. N. & Mayeda, T. K. Oxygen isotope fractionation in divalent metal carbonates. J. Chem. Phys. 51, 5547–5558 (1969).

Almeida, M. J., Machado, J., Moura, G., Azevedo, M. & Coimbra, J. Temporal and local variations in biochemical composition of Crassostrea gigas shells. J. Sea Res. 40, 233–249 (1998).

Steuber, T. & Veizer, J. Phanerozoic record of plate tectonic control of seawater chemistry and carbonate sedimentation. Geology 30, 1123–1126 (2002).

Voigt, S., Wilmsen, M., Mortimore, R. N. & Voigt, T. Cenomanian palaeotemperatures derived from the oxygen isotopic composition of brachiopods and belemnites: evaluation of Cretaceous palaeotemperature proxies. Int. J. Earth Sci. 92, 285–299 (2003).

Algeo, T. J. & Maynard, J. B. Trace-element behavior and redox facies in core shales of Upper Pennsylvanian Kansas-type cyclothems. Chem. Geol. 206, 289–313 (2004).

Freitas, P. S., Clarke, L. J., Kennedy, H., Richardson, C. A. & Abrantes, F. Environmental and biological controls on elemental (Mg/Ca, Sr/Ca and Mn/Ca) ratios in shells of the king scallop Pecten maximus. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 5119–5133 (2006).

Wierzbowski, H. & Joachimski, M. M. Reconstruction of late Bajocian–Bathonian marine palaeoenvironments using carbon and oxygen isotope ratios of calcareous fossils from the Polish Jura Chain (central Poland). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 254, 523–540 (2007).

Hesselbo, S. P. Sequence stratigraphy and inferred relative sea-level change from the onshore British Jurassic. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 119, 19–34 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Danish Council for Independent Research–Natural Sciences (project 09-072715) and the Carlsberg Foundation (project no 2011-01-0737) for contributions to financing this project provided for C.K.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.K. and S.P.H. designed the project and are responsible for the integrity of the study. C.K., S.P.H., C.V.U., G.D., M.R., G.S. and N.T. conducted the sampling in the field. C.K. and C.V.U. prepared, screened and analysed the samples. C.K. and S.P.H. mainly wrote the manuscript with contributions by C.V.U. and M.R., and in a close discussion with N.T., G.D. and G.S. in particular to the interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-2, Supplementary Tables 1-2 and Supplementary References (PDF 1238 kb)

Supplementary Data 1

Oxygen and carbon isotope data, selected element ratios, location, age, and fossil identification. New and previously published data are included. (PDF 1983 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Korte, C., Hesselbo, S., Ullmann, C. et al. Jurassic climate mode governed by ocean gateway. Nat Commun 6, 10015 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10015

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10015

This article is cited by

-

Early Jurassic extrinsic solar system dynamics versus intrinsic Earth processes: Toarcian sedimentation and benthic life in deep-sea contourite drift facies, Cardigan Bay Basin, UK

Progress in Earth and Planetary Science (2024)

-

Lower Jurassic (Pliensbachian–Toarcian) marine paleoenvironment in Western Europe: sedimentology, geochemistry and organic petrology of the wells Mainzholzen and Wickensen, Hils Syncline, Lower Saxony Basin

International Journal of Earth Sciences (2024)

-

The rise of macropredatory pliosaurids near the Early-Middle Jurassic transition

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Middle Jurassic palaeoclimate changes within the central Ordos Basin based on palynological records

Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments (2023)

-

Glendonite-bearing concretions from the upper Pliensbachian (Lower Jurassic) of South Germany: indicators for a massive cooling in the European epicontinental sea

Facies (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.