Abstract

In class 1a ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), a substrate-based radical is generated in the α2 subunit by long-distance electron transfer involving an essential tyrosyl radical (Y122O·) in the β2 subunit. The conserved W48 β2 is ∼10 Å from Y122OH; mutations at W48 inactivate RNR. Here, we design a beta hairpin peptide, which contains such an interacting tyrosine–tryptophan dyad. The NMR structure of the peptide establishes that there is no direct hydrogen bond between the phenol and the indole rings. However, electronic coupling between the tyrosine and tryptophan occurs in the peptide. In addition, downshifted ultraviolet resonance Raman (UVRR) frequencies are observed for the radical state, reproducing spectral downshifts observed for β2. The frequency downshifts of the ring and CO bands are consistent with charge transfer from YO· to W or another residue. Such a charge transfer mechanism implies a role for the β2 Y-W dyad in electron transfer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The aromatic amino-acid residues, tyrosine and tryptophan, mediate high potential electron transfer reactions in proteins1. For example, ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) employs a tyrosine-based charge relay to reduce ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides2. The reaction is initiated by H atom abstraction at the substrate 3′-carbon; this process employs an active site cysteine radical in the α2 subunit. Class Ia RNRs, such as the Escherichia coli RNR, use a tyrosyl radical (Y122O·)-diferric cofactor in the β2 subunit to generate the cysteine radical. The charge transfer between Y122 and C439 occurs over 35 Å and is mediated by a conserved pathway of tyrosine side chains3. Y122O· is required for activity4 and is formed via oxygen-requiring reactions at the diferric cluster4,5,6.

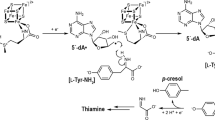

Although there is no high-resolution structure of Y122O·-diferric β2, in structures of the met state (Y122OH-diferric state)7, Y122OH is buried in a hydrophobic environment and is ∼10 Å (Fig. 1a) from a surface-exposed tryptophan, β2 W48. This tryptophan is highly conserved in class 1a β2 sequences8. Mutations at W48 in E. coli β2 or at the homologous position, W103 in mouse β2 (Fig. 1b)9, inactivate RNR8,10,11,12. This residue has been shown to participate in cofactor assembly10. However, its role in proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) has not been established3. The orientations of Y122OH and W48 in the crystal structure of the Y122OH-diferric state suggest the possibility of electronic, dipole–dipole interaction between the two side chains. In addition, the resonance Raman spectrum of Y122O· reveals downshifted CO and aromatic ring stretching frequencies. The low ring stretching frequency is not readily explained by existing model compounds13.

The structures were generated with Pymol from 1MXR (E. coli, a) and 1W69 (mouse, b). In a, Y122 and W48 are shown, along with iron cluster ligands, D84, E115, H118, E204, E238 and H241 in E. coli. In b, Y177 and W103 are shown, along with iron ligands D139, E170, H173, E233, E267 and H270 in mouse. The distance between the phenolic oxygen and the indole nitrogen is 9.7 Å in E. coli and 9.9 Å in mouse. Primary sequences and NMR structures of Peptide A (c,d) and Peptide M (e,f). (d,f) The averaged, minimized NMR structures. The Peptide A structure was reported previously17, and the Peptide M structure is derived from this work. Structural analyses for the ensemble of 20 low energy NMR models are presented in Supplementary Tables 4 (Peptide M) and 5 (Peptide A) in the Supplementary Information, as well as side chain–side chain distances in the averaged, minimized structures.

Despite the low sequence similarity between the E. coli and mammalian β2 subunits, the staggered T-shaped arrangement of tyrosine and tryptophan is similar when E. coli7, mouse9 and human p53 (ref. 14) β2 subunits are compared. Also, other metalloproteins containing redox active tyrosines, such as photosystem II (ref. 15) and galactose oxidase16, contain tyrosine–tryptophan dyads with a similar structure.

In this study, we designed a β hairpin peptide, Peptide M, to characterize the functional and spectroscopic consequences of such an interacting tyrosine–tryptophan pair. Peptide M is an 18-mer and is a variant of Peptide A (Fig. 1c), previously shown to form a β-hairpin (Fig. 1d)17,18. Peptide M (Fig. 1e) contains a single tyrosine and a single tryptophan, which form a dyad (Y5-W14), as established here by NMR, ultraviolet absorption and circular dichroism (CD) spectropolarography. The ultraviolet resonance Raman (UVRR) spectrum of Peptide M is unique and provides a framework in which to interpret the Raman spectra, previously reported for Y122O· in class 1a E. coli β2. Although there were earlier studies of (for example, see refs 19, 20) singlet states in model tyrosine–tryptophan peptides, we describe the first peptide in which interactions between the tyrosyl radical and the tryptophan sidechain are probed. The results are relevant to RNR and to other metalloproteins that employ redox-active tyrosines in high potential charge transfer pathways21,22.

Results

NMR studies

Peptide M is a variant of β-hairpin, Peptide A (Fig. 1c,d), in which H14 is replaced with W (Fig. 1e,f). For Peptide A, the NMR structure has shown that the peptide is β hairpin, that H14 has a pi–pi cross-strand interaction with Y5, and that Y5 is hydrogen bonded to R16 (ref. 17). To assess the structure of Peptide M in solution, we performed NMR experiments at pH ∼5. The NMR data are summarized in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Tables 1–3 in the Supplementary Information. The rotating frame Overhauser enhancement (ROE) pattern (Fig. 2a) with several (i, i+1) connectivities and 3JHα-HN coupling constants greater than 7 Hz for residues 5, 7, 10, 12, 13, 15 and 16 are typical of β strands. Also, several long-range dipolar contacts were observed between residues 2–17, 3–16, 5–14 and 6–13, supporting the β sheet fold of the peptide (Supplementary Fig. 1). The NMR data resulted in an ensemble of 20 selected conformers (Fig. 2c) with a root-mean-square deviation of 0.59±0.17 and 1.68±0.31 Å for backbone and side chains heavy atoms. The average structure (Figs 1f and 2d) shows that the aromatic residues (Y5 and W14) are co-facially aligned, as supported by seven inter-residue contacts between the aromatics, including ROEs between the ɛ protons of Y5 and CH2β and ɛ of W14. These NMR experiments show that the tyrosine and tryptophan are ∼6 Å apart and exhibit a pi-stacked, staggered interaction, which is reminiscent of the orientation observed in the β2 dyad. In Peptide M, tyrosine is not hydrogen bonded to tryptophan (distance greater than 5.9 Å in all models).

(a) Plot showing the short- and long-range ROEs for the backbone and the side chains, (b) root-mean-square deviations (RMSD) of the backbone atoms, (c) ensemble of 20 selected backbone conformers and (d) average structure of Peptide M. Resonance assignments were carried out using a combination of 2D [1H–1H]-TOCSY and [1H–1H]-ROESY experiments. All of the resonances were assigned, and 159 ROESY connectivities were detected. See Methods for more information, and the Supplementary Information for a table of ROE values used in calculations.

Seven of the twenty lowest energy conformers of the Peptide M ensemble display distances consistent with a hydrogen bond between the hydroxyl group of Y5 and NH of R16 (distance less than 3.0 Å, Supplementary Table 4). In Peptide A, Y5 is predicted to hydrogen bond as a proton acceptor to R16NH (distance less than 3 Å) in 6 of the 20 models and as a proton acceptor to R16NɛH in 4 of the 20 models (Supplementary Table 5). In the averaged, minimized structure of Peptide A, tyrosine is predicted to hydrogen bond to R16NɛH (Supplementary Table 5 and Fig. 1d). These results indicate that there is some probability of a hydrogen-bonding interaction between Y5 and R16 in both peptides. The dynamic nature of the peptide enables the formation of several stable as well as transient hydrogen bonds. Nonetheless, these residues are exposed to the bulk solvent, and intramolecular hydrogen bonds compete with formation of hydrogen bonds to water.

Circular dichroism

Figure 3b,c presents CD data acquired from Peptide M. The characteristic β-hairpin CD signal has maximum negative ellipticity at 198 nm and arises from the n–pi* transition of the amide backbone17,18. Similar to Peptide A (Fig. 3a), Peptide M exhibits this characteristic β-hairpin band and reversibly folds both at pH 6.5 and 11. As shown, spectra obtained before (solid line) and after (dashed line) a thermal melt (80 °C, dot–dashed line) exhibit the characteristic negative 198 nm band of the β-hairpin. At both pH values, spectra obtained pre-melt (purple, solid line) and post-melt (purple, dashed line) are similar. Further, β-hairpin signal is lost at 80 °C (purple, dot–dashed line), consistent with thermal melting. These experiments establish that Peptide M has a stable, β-hairpin fold.

Data were acquired from Peptide A, pH 6.5 (a, pink) Peptide M, pH 6.5 (b, purple) and Peptide M, pH 11 (c, purple). The spectra were obtained at 20 °C (solid line, pre-melt), 80 °C (dot–dashed line) or at 20 °C (dashed line, post-melt). In b, difference CD spectra are shown in cyan, corresponding to Peptide M pH 6.5 (b, purple)–minus–Peptide A (a, pink). In c, difference spectra are shown in cyan, corresponding to Peptide M pH 11 (c, purple)–minus–Peptide A (a, pink). Data were obtained at 20 °C (b,c, cyan, solid line, pre-melt) or at 80 °C (b,c, dot–dashed line). The analyte concentration was 200 μM, and the buffer contained 5 mM MES, pH 6.5 (a,b) or 5 mM borate, pH 11 (C). The spectra were averaged from three independent measurements. The tick marks denote 2 mdeg. Difference CD spectra (cyan) in b,c are multiplied by a factor of 2 for presentation purposes.

Ultraviolet–visible absorption spectra

Figure 4a presents the ultraviolet absorption spectrum of Peptide M at pH 5 (I, purple) and pH 11 (II, purple). In the 200- to 300-nm region, the spectra of tyrosine (C) and tryptophan (B) are dominated by pi–pi* transitions of the phenol and indole rings. As expected, Peptide M (A) exhibits absorption bands similar to those of tyrosine and tryptophan. However, the Peptide M tyrosine spectrum is perturbed compared with solution models. Subtraction (D) of the aqueous tryptophan spectrum from that of Peptide M reveals a red-shift, both at pH 5 and 11 (I and II, black dashed line). Note that subtraction of the tyrosine spectrum from that of Peptide M yields spectra that resemble tryptophan (Supplementary Fig. 2, grey dotted line), with some minor perturbation, except for the region below 260 nm, which is the onset of the peptide bond absorption. Previous gas phase and computational studies of indole-benzene, indole-pyridine and indole-imidazole heterodimers have shown a stabilization of the S0 state, attributed to NH hydrogen bonding, NH– and CH–pi interactions and pi–pi interactions in the dimers23,24,25. Thus, the red shift of the tyrosine ultraviolet spectrum in Peptide M is attributable to the close proximity of the cross-strand Y5 and W14 to form a Y5-W14 dyad.

Data were acquired from Peptide M (purple), tyrosine (Tyr; blue) and tryptophan (Trp; green) at pH 5 (I) and at pH 11 (II). The black dashed trace (D) was obtained by subtracting the tryptophan spectrum from that of Peptide M. The analyte concentration was 100 μM, and the buffer contained 5 mM acetate, pH 5 (I) or 5 mM borate, pH 11 (II). The spectra were averaged from two independent measurements. The tick marks denote 0.1 absorbance unit.

Excitonic splitting

A through-space aromatic–aromatic interaction between two pi–pi* transitions with similar energies can result in excitonic splitting, which is detectable in the CD spectrum26. The red shift of the Peptide M tyrosine spectrum led us to search for characteristic exciton splitting in the CD spectra of this peptide. Examination of Fig. 3b (pH 6.5) and Fig. 3c (pH 11) showed a differential band, which is superimposed on the β strand 198 nm signal. Peptide A, which lacks the Y5-W14 dyad, did not exhibit this feature (Fig. 3a).

This excitonic feature is clearly seen when the CD spectrum of Peptide A is subtracted from that of Peptide M, revealing the characteristic excitonic splitting with a negative feature at 212–216 nm and a positive component at 228 nm. The amplitude of this excitonic couplet signal decreased at 80 °C, indicating sensitivity to thermal melting of the peptide. Excitonic coupling leads to the splitting of the excited state into two components because of delocalization over the two monomers. Previous studies of PagP have identified an excitonic couplet (negative, ∼225 nm; positive 230 nm) between Trp66 and Tyr26 (ref. 27). Such an excitonic splitting between the 1Bb band of tryptophan and the 1La band of tyrosine can occur only if the indole and phenol side chains are in close proximity and fulfill geometric restraints on the orientations of the two transition moments. We conclude that the tryptophan and tyrosine in Peptide M form an excitonically interacting, aromatic pair via a dipole–dipole interaction.

Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV)

To characterize the properties of the dyad, we performed DPV, and the results are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3. The peak potential of tyrosine exhibits linear dependence on pH below the pKa of the phenolic oxygen (10)28. Using DPV, the peak potentials of tyrosine (blue) were determined to be 0.99±0.01 and 0.65±0.01 V at pH 5 and 11, respectively. The voltammograms acquired from tyrosine were irreversible, as previously reported, because of a contribution from competing reactions28. However, these peak potentials agree with reported midpoint potentials, implying that any correction factor is small17,28,29. Y5 in Peptide A (pink) gave peak potentials of 1.00±0.01 V (pH 5) and 0.71±0.02 V (pH 11) versus normal hydrogen electrode (NHE), similar to peak potentials of aqueous tyrosine and to values previously reported for this peptide17.

The peak potentials of Peptide M, aqueous tryptophan and an aqueous mixture of tyrosine and tryptophan (Supplementary Fig. 3A,B) were similar both at pH 5 and pH 11, given the standard deviation of the measurements. The values obtained at pH 5 and 11 for Peptide M (1.02±0.02 and 0.72±0.01 V versus NHE, respectively) were in good agreement with values previously reported for the midpoint potential of tryptophan28,29. We conclude that the electronic interaction between tryptophan and tyrosine in Peptide M does not have a large effect on the peak potential of the amino-acid side chain. This implies that stabilization of the singlet and the radical state are similar in Peptide M, suggesting that Y5 interacts with W14 in both states.

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy

Next, we sought to examine the radical state of Y5 in order to establish whether tyrosyl radical structure is altered in Peptide M. To examine the radical state, ultraviolet photolysis and EPR spectroscopy can be performed. However, the breadth of the X-band EPR spectra precludes the detection of small differences in radical structure. This is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 4, in which photolysis at 266 nm was used to generate both tyrosyl (Supplementary Fig. 4D) and tryptophan (Supplementary Fig. 4C) radicals in frozen solutions or powders (160 K) of the isolated amino acids. The EPR of the tyrosyl and tryptophan radicals agree in lineshape and g value with earlier reports30,31. Ultraviolet photolysis of Peptide M (Supplementary Fig. 4B) gave an EPR lineshape similar to the spectrum of an aqueous mixture of tyrosine and tryptophan (Supplementary Fig. 4C) and of Peptide A (Supplementary Fig. 4A). However, small changes due to the environment are not detectable. Note that this procedure does not cause significant modification of the samples as assessed by the ultraviolet–visible absorption before and after photolysis (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Ultraviolet resonance Raman studies

To more incisively probe the structure of the tyrosyl radical and singlet state, UVRR spectra were acquired at pH 11 using 244 nm excitation. Previous work has shown that tyrosyl radical can be generated by 244 nm, continuous illumination of aqueous tyrosine at room temperature13,32. This procedure does not result in modification of the peptide, as assessed by mass spectrometry. Raman excitation at 244 nm is specific for the tyrosyl radical and the tyrosine singlet, because of resonance enhancement of the tyrosine electronic transition relative to that of tryptophan. The Raman bands due to tyrosyl radical and tyrosine singlet state are highlighted in difference spectra (high power scan minus low power scan). The positive bands correspond to the vibrational modes of the radical, whereas the negative bands correspond to the singlet vibrational modes.

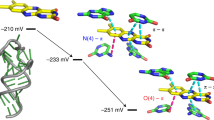

The UVRR difference spectrum obtained from aqueous tyrosine is shown in Fig. 5d. Positive bands at 1,410, 1,514 and 1,574 cm−1 are assigned to ring stretching (Y19a), C–O stretching (Y7a) and C–C ring (Y8a) stretching modes of the radical, respectively (Table 1). The negative bands at 1,172, 1,206 and 1,600 cm−1 arise from the CH bend (Y9a), ring C–CH2 (Y7a) and a ring Y8a mode of the singlet state13,32. As expected, 244 nm excitation of aqueous tryptophan did not produce a Raman difference spectrum (Fig. 5e). The difference spectrum of an aqueous tyrosine–tryptophan mixture (Fig. 5c) was indistinguishable (±2 cm−1) from that of tyrosine alone, again showing the specificity of this Raman probe wavelength for tyrosine.

UVRR difference spectra derived from Peptide M, Peptide A and model compounds. Data were acquired from Peptide M (A), Peptide A (B), a tyrosine-tryptophan solution (C), a tyrosine solution (D) or a tryptophan solution (E). The analyte concentration was 1 mM, and the buffer was 5 mM borate, pH 11. The difference spectrum was obtained by subtracting an averaged low-power scan (340 μW) from an averaged high-power scan (3.4 mW). The tick marks denote 50 intensity units. The data were averaged from at least two independent measurements. The asterisks in A denote unique frequencies of the YO·-W dyad.

Figure 5a presents UVRR difference spectrum of Peptide M. The frequencies and intensities of the singlet Raman bands were identifiable using data acquired from the tryptophan–tyrosine mixture and a tyrosine solution. A shift in the frequency of the singlet Y8a, from 1,600 cm−1 in tyrosine (Fig. 5d) to 1,603 cm−1 in Peptide M (Fig. 5a), may not be significant, relative to the uncertainty in peak position (±2 cm−1). The Y9a band is conformationally sensitive and exhibits a modest shift (4 cm−1) when Peptide M is compared with tyrosine.

In contrast, the frequencies of the positive radical bands were significantly shifted in Peptide M, compared with those derived from tyrosine, a solution of tyrosine and tryptophan, and Peptide A (Fig. 5b and Table 1)13,32. For example, the radical ring stretch (Y19a) shifts from 1,410 cm−1 in tyrosine to 1,402 cm−1 in Peptide M (Table 1). In addition, the radical CO stretch (Y7a) and the ring stretch (Y8a) bands were 1,514 and 1,574 cm−1 in the tyrosine model compound (Fig. 5d) but were 1,503 and 1,566 cm−1 in Peptide M (Fig. 5a, peaks labelled with asterisks). Radical frequencies in Peptide A were indistinguishable from that of tyrosine and were 1,410 (Y19a), 1,516 (Y7a) and 1,572 (Y8a) cm−1 (Table 1 and see also ref. 32). We conclude that substantial 8–11 cm−1 Raman shifts are diagnostic for an aromatic–aromatic interaction between the tyrosyl radical and a tryptophan side chain in a YO·-W dyad.

Discussion

In β2 or other complex proteins, a detailed picture of interaction between Y and W is difficult to obtain, because of background signals from other tyrosines, tryptophans and the peptide backbone. De novo designed peptides provide structurally tractable backgrounds in which to elucidate function (for examples, see refs 29, 33, 34). For instance, studies of the β-hairpin, Peptide A, have demonstrated that the peptide environment accelerates the rate of electron and proton-coupled electron transfer35 and provide a model system for investigating orthogonal proton and electron transfer involving tyrosine and histidine17,18. Also, UVRR spectroscopy has shown that a reversible conformational change accompanies electron or proton-coupled electron transfer in Peptide A32.

To understand the spectroscopic and functional properties of a tyrosine–tryptophan dyad, we designed and synthesized a β-hairpin maquette, Peptide M, which contains a tyrosine–tryptophan cross-strand interacting pair. Peptide M forms a β-hairpin at pH 6.5 and 11 and can be reversibly folded and unfolded at both pH values. NMR experiments show that the tyrosine and tryptophan are ∼6 Å apart and exhibit a pi-stacked, staggered interaction, which is similar to the tyrosine/tryptophan orientation observed in β2. The ultraviolet and CD spectra of the peptide exhibit spectral shifts and splittings that are characteristic of S0 state stabilization and of a dipole–dipole-mediated electronic interaction between the indole and phenol groups, respectively. The peak potential and singlet Raman spectrum of Peptide M are not significantly perturbed, compared with the isolated amino acids or Peptide A. However, the Raman spectrum of the radical, Y5·-W14, dyad in Peptide M is distinct from that of tyrosine and Peptide A.

In model tyrosine, production of tyrosyl radical is associated with a dramatic upshift of the CO vibrational band (from ∼1,260 to 1,514 cm−1) and a downshift of the highest energy aromatic ring stretching mode (from ∼1,600 to 1,574 cm−1)13,36,37,38. The Y5·-W14 dyad in Peptide M (Fig. 5a) exhibits downshifted CO and ring stretching bands, relative to those of tyrosyl radical in aqueous solution (Fig. 5d) and Peptide A (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, downshifted CO and ring stretching frequencies have also been reported for Y122O·-W48 in E. coli β2 (refs 13, 36, 39). The CO band of the Y122O·-W48 dyad was detected at 1,498/1,499 cm−1 (refs 13, 36, 39), and the ring stretching mode was detected at 1,556 cm−1. The substantial downshifts observed in the Peptide M dyad suggest that the shifted Raman frequencies in E. coli β2 are due, at least in part, to an interaction between Y122O· and W48. The CO band has also been reported to be sensitive to hydrogen bonding and electrostatics40,41, but a factor that downshifts the frequency of the ring stretching bands has not been successfully modelled until this work (reviewed in ref. 42). Note that in the Peptide M structural ensemble calculated via NOE, there are no conformers showing the presence of an H-bond between Y5 and W14. However, seven of the lowest energy conformers show the presence of an H-bond between the side chains of Y5 and R16. Therefore, intramolecular hydrogen bonding does not provide an explanation for the downshifted Raman bands of Peptide M, when compared with Raman bands of Peptide A.

We attribute the downshift of the CO and ring frequencies of the tyrosyl radical to charge transfer from the tyrosyl radical in the Y·-W dyad. Precedent is established in previous studies of Old Yellow Enzyme, in which charge transfer between flavin cofactor and phenolic compounds resulted in shifts of phenol Raman bands43. Subtle changes in angle and distance are observed in the met state of E. coli and mouse β2; these changes in orientation could influence the amount of charge transfer. UVRR studies to detect both the ring and CO stretching mode in mammalian β2 will be useful in evaluating this possibility. Such subtle changes in orientation may be the foundation of the 4–8 cm−1 differences in band position, when RNR and Peptide M are compared. Note that the idea of conformational gating and tyrosyl radical movement has been proposed to explain the EPR and FTIR spectra of hydrogen peroxide-treated crystals7 and hydroxyurea-treated solution samples38, respectively. Therefore, the met Y122OH structure may not be predictive of all the interactions in the radical state.

In summary, Peptide M is the first reported model system that accounts for the downshifted CO and ring stretching vibrations of Y122O· in E. coli β2. The results presented here suggest that the E. coli β2 Y122O· radical interacts with W48. The decrease in vibrational frequencies for Y122O· is characteristic of an overall decrease in radical bond strength. This decrease can be associated with delocalization of electron density onto the W48 indole ring or onto another nearby site in the protein. Note that a small amount of charge transfer from the tyrosyl radical to another site would be difficult to detect with magnetic resonance techniques. However, this transfer of charge may be an important element in guiding electron transfer through the hydrogen-bonding network of β2. This charge transfer motif may also operate in other metalloproteins, which employ redox-active tyrosine residues.

Methods

Material

Peptides were synthesized by solid-state synthesis and were obtained from Genscript USA Inc. 2H2O and NaO2H were purchased from Cambridge Isotopes (99.9% D). When 2H2O was used, the p2H was adjusted to the uncorrected metre reading44. 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES), N-cyclohexyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid (CAPS), 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazin-1-yl]ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), tyrosine and tryptophan were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium borate was purchased from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, and boric acid was purchased from J.T. Baker Avantor Performance Materials. Hexamine ruthenium (III) chloride was purchased from Strem Chemicals.

NMR

The NMR samples were prepared by dissolving 1 mg of peptide in 350 μM sodium phosphate buffer (pH ∼5) containing 5% 2H2O. The spectra were acquired on a 700-MHz Bruker spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance cryogenic probe. A [1H,1H]-total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) experiment with 70 ms mixing time and spectral widths of 7,122.5 Hz for both dimensions was utilized to assign all of the peptide resonances. MLEV17 with field strength of 9 kHz was used as a mixing sequence45. To determine the inter-nuclear distances, we utilized a series of [1H,1H]-rotating frame nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (ROESY) experiments with spectral widths identical to the TOCSY experiments, and with a continuous wave mixing sequence using 100, 200, 250, 350 and 400 ms mixing times46. The NMR spectra were processed using NMRPipe47 and analysed using Sparky48 software packages. The spectra were referenced to the water resonance at 4.7 p.p.m. TOCSY and ROESY spectra were assigned using the standard approach described by Wuthrich49. Based on the build-up curve, ROESY cross-peaks at 350 ms were chosen for structure calculations. A total of 156 ROEs consisting of 65 intra-residue and 91 inter-residue correlations were used for structure determination. Peak intensities were converted into distances using the following classifications: strong (1.8–2.9 Å), medium (1.8–3.6 Å) and weak (1.8–6.0 Å). For residues with 3JNH-Ha>8.0 Hz φ, angles were restricted to the range of –160 to –80°. NMR conformers were calculated starting from an extended conformation of Peptide M and using a hybrid simulated annealing protocol available in the XPLOR-NIH package50. Briefly, calculations were carried out using an initial temperature of 1,000 K, 50,000 high temperature steps and 6,000 cooling steps with a step size of 5 fs decreasing the temperature from 1,000 to 100 K. The generated conformers were further minimized including the Lennard-Jones potential, with the Conjugated Gradients algorithm using an initial temperature of 300 K and 60,000 steps (step size 1 fs). A total of 50 conformers were generated; the 20 lowest energy conformers without NOE violations greater than 0.5 Å, no bond violations greater than 0.05 Å, and no bond violations greater than 4° were selected for further analysis. Measurements were conducted both at 278 and 298 K.

Circular dichroism

A Jasco J-810 CD spectropolarimeter equipped with a Peltier-type cell was employed. Spectra were collected from 250 to 193 nm in 1 mm quartz cells. Eight accumulations per scan were averaged in three independent measurements for each of the conditions. Parameters used were: sensitivity, 100 mdeg; data pitch, 2 nm; scan speed, 50 nm min−1; response time, 1 s; bandwidth, 1 nm.

Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy

Ultraviolet absorption spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu UV-1700 spectrometer. The slit width was 1 nm, the resolution was 1 nm and the scan speed was 6.5 nm s−1. The spectra were averaged from two independent measurements.

Ultraviolet resonance Raman

UVRR spectra of 1 mM samples were obtained at room temperature using a 244-nm probe beam generated from an intracavity frequency-doubled Argon ion laser (Cambridge LEXEL 95)32,51. Briefly, the probe beam was coupled to a Raman microscope system (Renishaw inVia) equipped with ultraviolet-coated, deep depletion charge-coupled device. Backscattering from the sample was collected by a 15 × ultraviolet (NA=0.32) objective (OFR division of Thorlabs, Inc.), assembled in a Leica Microsystems microscope. The spectral resolution was 6 cm−1, and the interval between the data points was 3.8 cm−1. The peak positions are reported to a precision of ±2 cm−1. To prevent photodegradation, samples were re-circulated using a peristaltic pump and a nozzle (∼120 μm inner diameter) to form a jet. The Raman difference spectrum was obtained by subtracting an averaged low power scan (340 μW) from an averaged high power scan (3.4 mW) using 244 nm beam. The data were averaged from at least two measurements on different samples. Mass spectrometry (ThermoFisher Scientific, LTQ Orbitrap XL, Electrospray ionization, Positive Ion Mode) before and after the Raman measurement gave the expected 1,195 m/z ratio for Peptide M, indicating that there was no significant oxidative modification of the peptide during the UVRR measurement.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Pagba, C. V. et al. A tyrosine–tryptophan dyad and radical-based charge transfer in a ribonucleotide reductase-inspired maquette. Nat. Commun. 6:10010 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10010 (2015).

References

Dempsey, J. L., Winkler, J. R. & Gray, H. B. Proton-coupled electron flow in protein redox machines. Chem. Rev. 110, 7024–7039 (2010).

Stubbe, J. A. & vanderDonk, W. A. Ribonucleotide reductases: radical enzymes with suicidal tendencies. Chem. Biol. 2, 793–801 (1995).

Minnihan, E. C., Nocera, D. G. & Stubbe, J. Reversible, long-range radical transfer in E. coli class la ribonucleotide reductase. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 2524–2535 (2013).

Larsson, A. & Sjoberg, B. M. Identification of the stable free-radical tyrosine residue in ribonucleotide reductase. EMBO J. 5, 2037–2040 (1986).

Atkin, C. L., Thelande., L., Reichard, P. & Lang, G. Iron and free-radical in ribonucleotide reductase - exchange of iron and Mossbauer-spectroscopy of protein-β2 subunit of Escherichia coli enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 248, 7464–7472 (1973).

Bollinger, J. M. et al. Mechanism of assembly of the tyrosyl radical dinuclear iron cluster cofactor of ribonucleotide reductase. Science 253, 292–298 (1991).

Hogbom, M. et al. Displacement of the tyrosyl radical cofactor in ribonucleotide reductase obtained by single-crystal high-field EPR and 1.4Å X-ray data. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 3209–3214 (2003).

Kauppi, B. et al. The three-dimensional structure of mammalian ribonucleotide reductase protein R2 reveals a more-accessible iron-radical site than Escherichia coli R2. J. Mol. Biol. 262, 706–720 (1996).

Strand, K. R. et al. Crystal structural studies of changes in the native dinuclear iron center of ribonucleotide reductase protein R2 from mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 46794–46801 (2004).

Saleh, L. et al. Mediation by indole analogues of electron transfer during oxygen activation in variants of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase R2 lacking the electron-shuttling tryptophan 48. Biochemistry 43, 5943–5952 (2004).

Krebs, C. et al. Mechanism of rapid electron transfer during oxygen activation in the R2 subunit of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase 2. Evidence for and consequences of blocked electron transfer in the W48F variant. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 12207–12219 (2000).

Rova, U. et al. Evidence by site-directed mutagenesis supports long-range electron-transfer in mouse ribonucleotide reductase. Biochemistry 34, 4267–4275 (1995).

Barry, B. A. et al. Proton-coupled electron transfer and redox-active tyrosines: Structure and function of the tyrosyl radicals in ribonucleotide reductase and photosystem II. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 543–554 (2012).

Smith, P. et al. 2.6Å X-ray crystal structure of human p53R2, a p53-inducible ribonucleotide reductase. Biochemistry 48, 11134–11141 (2009).

Umena, Y., Kawakami, K., Shen, J. R. & Kamiya, N. Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9Å. Nature 473, 55–U65 (2011).

Ito, N. et al. Novel thioether bond revealed by a 1.7Å crystal-structure of galactose-oxidase. Nature 350, 87–90 (1991).

Sibert, R. et al. Proton-coupled electron transfer in a biomimetic peptide as a model of enzyme regulatory mechanisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 4393–4400 (2007).

Sibert, R. S., Josowicz, M. & Barry, B. A. Control of proton and electron transfer in de novo designed, biomimetic beta hairpins. ACS Chem. Biol. 5, 1157–1168 (2010).

Makwana, K. M. & Mahalakshmi, R. NMR analysis of tuning cross-strand phe/tyr/trp–trp interactions in designed β-hairpin peptides: Terminal switch from L to D amino acid as a strategy for β-hairpin capping. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 5376–5385 (2015).

Wu, L., McElheny, D., Takekiyo, T. & Keiderling, T. A. Geometry and efficacy of cross-strand trp/trp, trp/tyr, and tyr/tyr aromatic interaction in a β-hairpin peptide. Biochemistry 49, 4705–4714 (2010).

Polizzi, N. F., Migliore, A., Therien, M. J. & Beratan, D. N. Defusing redox bombs? Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 10821–10822 (2015).

Gray, H. B. & Winkler, J. R. Hole hopping through tyrosine/tryptophan chains protects proteins from oxidative damage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 10920–10925 (2015).

Braun, J., Neusser, H. J. & Hobza, P. N−H···π Interactions in indole···benzene-h6,d6 and indole···benzene-h6,d6 radical cation complexes. Mass analyzed threshold ionization experiments and correlated ab initio quantum chemical calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A 107, 3918–3924 (2003).

Kumar, S., Biswas, P., Kaul, I. & Das, A. Competition between hydrogen bonding and dispersion interactions in the indole···pyridine dimer and (indole)(2)···pyridine trimer studied in a supersonic jet. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 7461–7472 (2011).

Hill, J. G. & Das, A. Interaction in the indole···imidazole heterodimer: structure, Franck-Condon analysis and energy decomposition. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 11754–11762 (2014).

Grishina, I. B. & Woody, R. W. Contributions of tryptophan side-chains to the circular-dichroism of globular-proteins - exciton couplets and coupled oscillators. Faraday Discuss. 99, 245–262 (1994).

Khan, M. A. et al. Gauging a hydrocarbon ruler by an intrinsic exciton probe. Biochemistry 46, 4565–4579 (2007).

Harriman, A. Further comments on the redox potentials of tryptophan and tyrosine. J. Phys. Chem. 91, 6102–6104 (1987).

Tommos, C., Skalicky, J. J., Pilloud, D. L., Wand, A. J. & Dutton, P. L. De novo proteins as models of radical enzymes. Biochemistry 38, 9495–9507 (1999).

Barry, B. A., Eldeeb, M. K., Sandusky, P. O. & Babcock, G. T. Tyrosine radicals in photosystem II and related model compounds - characterization by isotopic labeling and EPR spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 20139–20143 (1990).

Stoll, S. et al. Hydrogen bonding of tryptophan radicals revealed by EPR at 700 GHz. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 18098–18101 (2011).

Pagba, C. V. & Barry, B. A. Redox-induced conformational switching in photosystem-II-inspired biomimetic peptides: a UV resonance Raman study. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 10590–10599 (2012).

Handel, T. & DeGrado, W. F. De novo design of a Zn2+-binding protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 6710–6711 (1990).

Reedy, C. J. & Gibney, B. R. Heme protein assemblies. Chem. Rev. 104, 617–649 (2004).

Pagba, C. V., Chi, S. H., Perry, J. & Barry, B. A. Proton-coupled electron transfer in tyrosine and a beta-hairpin maquette: reaction dynamics on the picosecond time scale. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 2726–2736 (2015).

Offenbacher, A. R., Vassiliev, I. R., Seyedsayamdost, M. R., Stubbe, J. & Barry, B. A. Redox-linked structural changes in ribonucleotide reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 7496–7497 (2009).

Offenbacher, A. R., Minnihan, E. C., Stubbe, J. & Barry, B. A. Redox-linked changes to the hydrogen-bonding network of ribonucleotide reductase β2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 6380–6383 (2013).

Offenbacher, A. R., Burns, L. A., Sherrill, C. D. & Barry, B. A. Redox-linked conformational control of proton-coupled electron transfer: Y122 in the ribonucleotide reductase β2 subunit. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 8457–8468 (2013).

Backes, G., Sahlin, M., Sjoberg, B. M., Loehr, T. M. & Sandersloehr, J. Resonance Raman-spectroscopy of ribonucleotide reductase - evidence for a deprotonated tyrosyl radical and photochemistry of the binuclear iron center. Biochemistry 28, 1923–1929 (1989).

Spanget-Larsen, J. et al. Vibrations of the phenoxyl radical. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 11253–11261 (2001).

Tomter, A. B. et al. HF-EPR, Raman, UV/Vis light spectroscopic, and DFT studies of the ribonucleotide reductase R2 tyrosyl radical from Epstein-Barr virus. PLoS ONE 6, e25022 (2011).

Barry, B. A. Reaction dynamics and proton coupled electron transfer: Studies of tyrosine-based charge transfer in natural and biomimetic systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1847, 46–54 (2015).

Kitagawa, T. et al. Resonance Raman evidence for charge-transfer interactions of phenols with the flavin mononucleotide of Old Yellow Enzyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101, 3376–3378 (1979).

Jenson, D. L. & Barry, B. A. Proton-coupled electron transfer in photosystem II: Proton inventory of a redox active tyrosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 10567–10573 (2009).

Bax, A. & Davis, D. G. MLEV-17 based two-dimensional homonuclear magnetization transfer spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 65, 355–360 (1985).

Bax, A. & Davis, D. G. Practical aspects of two-dimensional transverse NOE spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 63, 207–213 (1985).

Delaglio, F. et al. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 (1995).

Goddard, T. D. & Kneller, D. G. SPARKY 3. Univ. California, San Francisco 14, 15 (2004).

Wuthrich, K. NMR of Proteins and Nucleic Acids Wiley (1986).

Schwieters, C. D., Kuszewski, J. J., Tjandra, N. & Marius Clore, G. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson. 160, 65–73 (2003).

Chen, J. & Barry, B. A. Ultraviolet resonance Raman microprobe spectroscopy of photosystem II. Photochem. Photobiol. 84, 815–818 (2008).

Acknowledgements

Supported by NSF CLP CHE-1213350 (B.A.B.) and NIH GM-100310 (G.V.). T.G.M. was partially supported by a GAANN program in Molecular Biophysics and Biotechnology from the Department of Education. We thank Professor N. Hud and Professor J. Reynolds for the use of the CD and the potentiostat, respectively. We are grateful to Dr A. Österholm for advice concerning the DPV measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.V.P., T.G.M., Z.G., F.P. and G.V. conducted experiments, analysed data and assisted with the manuscript preparation; F.P. performed the structure calculations; J.Y. and M.M. conducted experiments, and B.A.B. designed the research, analysed data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-5, Supplementary Tables 1-5 and Supplementary References (PDF 1097 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Pagba, C., McCaslin, T., Veglia, G. et al. A tyrosine–tryptophan dyad and radical-based charge transfer in a ribonucleotide reductase-inspired maquette. Nat Commun 6, 10010 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10010

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10010

This article is cited by

-

In memoriam of Professor Bridgette Barry (March 1, 1957–January 20, 2021)

Photosynthesis Research (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.