Abstract

Productivity of ruminant livestock depends on the rumen microbiota, which ferment indigestible plant polysaccharides into nutrients used for growth. Understanding the functions carried out by the rumen microbiota is important for reducing greenhouse gas production by ruminants and for developing biofuels from lignocellulose. We present 410 cultured bacteria and archaea, together with their reference genomes, representing every cultivated rumen-associated archaeal and bacterial family. We evaluate polysaccharide degradation, short-chain fatty acid production and methanogenesis pathways, and assign specific taxa to functions. A total of 336 organisms were present in available rumen metagenomic data sets, and 134 were present in human gut microbiome data sets. Comparison with the human microbiome revealed rumen-specific enrichment for genes encoding de novo synthesis of vitamin B12, ongoing evolution by gene loss and potential vertical inheritance of the rumen microbiome based on underrepresentation of markers of environmental stress. We estimate that our Hungate genome resource represents ∼75% of the genus-level bacterial and archaeal taxa present in the rumen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Climate change and feeding a growing global population are the two biggest challenges facing agriculture1. Ruminant livestock have an important role in food security2; they convert low-value lignocellulosic plant material into high-value animal proteins that include milk, meat and fiber products. Microorganisms present in the rumen3,4 ferment polysaccharides to yield short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs; acetate, butyrate and propionate) that are absorbed across the rumen epithelium and used by the ruminant for maintenance and growth. The rumen represents one of the most rapid and efficient lignocellulose depolymerization and utilization systems known, and is a promising source of enzymes for application in lignocellulose-based biofuel production5. Enteric fermentation in ruminants is also the single largest anthropogenic source of methane (CH4)6, and each year these animals release ∼125 million tonnes of CH4 into the atmosphere. Targets to reduce agricultural carbon emissions have been proposed7, with >100 countries pledging to reduce agricultural greenhouse gas emissions in the 2015 Paris Agreement of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Consequently, improved knowledge of the flow of carbon through the rumen by lignocellulose degradation and fermentation to SCFAs and CH4 is relevant to food security, sustainability and greenhouse gas emissions.

Understanding the functions of the rumen microbiome is crucial to the development of technologies and practices that support efficient global food production from ruminants while minimizing greenhouse gas emissions. The Rumen Microbial Genomics Network (http://www.rmgnetwork.org/) was launched under the auspices of the Livestock Research Group of the Global Research Alliance (http://globalresearchalliance.org/research/livestock/) to further this understanding, with the generation of a reference microbial genome catalog—the Hungate1000 project—as a primary collaborative objective. Although the microbial ecology of the rumen has long been the focus of research8,9, at the beginning of the project reference genomes were available for only 14 bacteria and one methanogen, so that genomic diversity was largely unexplored.

The Hungate1000 project was initiated as a community resource in 2012, and the collection assembled includes virtually all the bacterial and archaeal species that have been cultivated from the rumens of a diverse group of animals10. We surveyed Members of the Rumen Microbial Genomics Network and requested they provide cultures of interest. We supplemented these with additional cultures purchased from culture collections to generate the most comprehensive collection possible. These cultures are available to researchers, and we envisage that additional organisms will have their genome sequences included as more rumen microbes are able to be cultivated.

Large-scale reference genome catalogs, including the Human Microbiome Project (HMP)11 and the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea (GEBA)12 have helped to improve our understanding of microbiome functions, diversity and interactions with the host. The success of these efforts has resulted in calls for continued development of high-quality reference genome catalogs13,14, and led to a resurgence in efforts to cultivate microorganisms15,16,17. This high-quality reference genome catalog for rumen bacteria and archaea increases our understanding of rumen functions by revealing degradative and physiological capabilities, and identifying potential rumen-specific adaptations.

Results

Reference rumen genomes

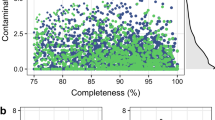

Members of nine phyla, 48 families and 82 genera (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Note 1) are present in the Hungate Collection. The organisms were chosen to make the coverage of cultivated rumen microbes as comprehensive as possible10. While multiple isolates were sequenced from some polysaccharide-degrading genera (Butyrivibrio, Prevotella and Ruminococcus), many species are represented by only one or a few isolates. 410 reference genomes were sequenced in this study, and were analyzed in combination with 91 publicly available genomes18. All Hungate1000 genomes were sequenced using Illumina or PacBio technology, and were assembled and annotated as summarized in the Online Methods. All genomes were assessed as high quality using CheckM19 with >99% completeness on average, and in accordance with proposed standards20. The genome statistics can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

The 501 sequenced organisms analyzed in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1. We refer to these 501 genomes (480 bacteria and 21 archaea) as the Hungate genome catalog. Supplementary Table 3 provides a comprehensive chronological list of all publicly available completed rumen microbial genome sequencing projects, including anaerobic fungi and genomes that have been recovered from metagenomes but that were not included in our analyses.

Members of the Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla predominate in the rumen21,22 and contribute most of the Hungate genome sequences (68% and 12.8%, respectively; Supplementary Fig. 1a), with the Lachnospiraceae family making up the largest single group (32.3%). Archaea are mainly from the Methanobrevibacter genus or are in the Methanomassiliicoccales order. The average genome size is ∼3.3 Mb (Supplementary Fig. 1b), and the average G+C content is 44%. Most organisms were isolated directly from the rumen (86.6%), with the remainder isolated from feces or saliva. Most cultured organisms were from bovine (70.9%) or ovine (17.6%) hosts, but other ruminant or camelid species are also represented (Table 1).

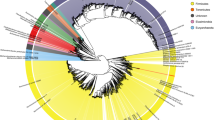

The Global Rumen Census project22 profiled the microbial communities of 742 rumen samples present in diverse ruminant species, and found that rumen communities largely comprised similar bacteria and archaea in the 684 samples that met the criteria for inclusion in the analysis. A core microbiome of seven abundant genus-level groups was defined for 67% of the Global Rumen Census sequences22. We overlaid 16S rRNA gene sequences from the 501 Hungate genomes onto the 16S rRNA gene amplicon data set from the Global Rumen Census project (Fig. 1). This revealed that our Hungate genomes represent ∼75% of the genus-level taxa reported from the rumen.

Two groups of abundant but currently unclassified bacteria are indicated by blue (Bacteroidales, RC-9 gut group) and orange (Clostridiales, R-7 group) dots. The colored rings around the trees represent the taxonomic classifications of each OTU from the Ribosomal Database Project database (from the innermost to the outermost): genus, family, order, class and phylum. The strength of the color is indicative of the percentage similarity of the OTU to a sequence in the RDP database of that taxonomic level.

Previous studies of the rumen microbiome have highlighted unclassified bacteria as being among the most abundant rumen microorganisms10,21, and we also report 73 genome sequences from strains that have yet to be taxonomically assigned to genera or phenotypically characterized (Supplementary Table 1). Most abundant among these uncharacterized strains are members of the order Bacteroidales (RC-9 gut group) and Clostridiales (R-7 group), and this abundance points to a key role for these strains in rumen fermentation22. The RC-9 gut group bacteria have small genomes (∼2.3 Mb), and the closest named relatives (84% identity of the 16S rRNA gene) are members of the genus Alistipes, family Rikenellaceae. The R-7 group are most closely related to Christensenella minuta (86% identity of the 16S rRNA gene), family Christensenellaceae.

Functions of the rumen microbiome

Polysaccharide degradation.

Ruminants need efficient lignocellulose breakdown to satisfy their energy requirements, but ruminant genomes, in common with the human genome, encode very limited degradative enzyme capacity. Cattle have a single pancreatic amylase23, and several lysozymes24 which functions as lytic digestive enzymes that can kill Gram-positive bacteria25.

We searched the CAZy database for each Hungate genome (http://www.cazy.org/)26 in order to characterize the spectrum of carbohydrate-active enzymes and binding proteins present (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 4). In total, the Hungate genomes encode 32,755 degradative CAZymes (31,569 glycoside hydrolases and 1,186 polysaccharide lyases), representing 2.2% of the combined ORFeome. The largest and most diverse CAZyme repertoires (Fig. 2a) were found in isolates with large genomes including Bacteroides ovatus (over 320 glycoside hydrolases (GH) and polysaccharide lyases (PL) from ∼60 distinct families), Lachnospiraceae bacterium NLAE-zl-G231 (296 GHs and PLs), Ruminoclostridium cellobioparum ATCC 15832 (184 GHs and PLs) and Cellvibrio sp. BR (158 GHs and PLs). The most prevalent CAZyme families are shown in Supplementary Figure 3. Bacteria that initiate the breakdown of plant fiber are predicted to be important in rumen microbial fermentation (Fig. 2b), including representatives of bacterial groups capable of degrading cellulose, hemicellulose (xylan/xyloglucan) and pectin (Fig. 2c).

(a) Number of degradative CAZymes (GH, glycoside hydrolases and PL, polysaccharide lyases) in distinct families in each of the 501 Hungate catalog genomes. Genomes are colored by phylum. (b) Simplified illustration showing the degradation and metabolism of plant structural carbohydrates by the dominant bacterial and archaeal groups identified in the Global Rumen Census project22 using information from metabolic studies and analysis of the reference genomes. The abundance and prevalence data shown in the table are taken from the Global Rumen Census project22. Abundance represents the mean relative abundance (%) for that genus-level group in samples that contain that group, while prevalence represents the prevalence of that genus-level group in all samples (n = 684).* The conversion of choline to trimethylamine, and propanediol to propionate generate toxic intermediates that are contained within bacterial microcompartments (BMC). Cultures from the reference genome set that encode the genes required to produce the structural proteins required for BMC formation are shown in Supplementary Table 5. (c) Number of polysaccharide-degrading CAZymes encoded in the genomes of representatives from the eight most abundant bacterial groups. Cellulose: GH5, GH9, GH44, GH45, GH48; pectin: GH28, PL1, PL9, PL10, PL11, CE8, CE12; xylan: GH8, GH10, GH11, GH43, GH51, GH67, GH115, GH120, GH127, CE1, CE2.

Examination of the CAZyme profiles (Supplementary Fig. 3) highlights the degradation strategies used by different taxa present in our collection. Members of the phylum Bacteroidetes have evolved polysaccharide utilization loci (PULs), genomic regions that encode all required components for the binding, transport and depolymerization of specific glycan structures. Predictions of PUL organization in all 64 Bacteroidetes genomes from the Hungate catalog have been integrated into the dedicated PULDB database27. The pectin component rhamnogalacturonan II (RG-II) is the most structurally complex plant polysaccharide, and all the CAZymes required for its degradation occur in a single large PUL recently identified in Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron28. Similar PULs encoding all necessary enzymes were also found in rumen isolates belonging to three different families within the phylum Bacteroidetes (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 4). Another feature of the Bacteroidetes genomes and PULs is the prevalence of GH families dedicated to the breakdown of animal glycans (Supplementary Figure 2). Host glycans are not thought to be used as a carbohydrate source for rumen bacteria, and most of the genomes with extensive repertoires of these enzymes (Bacteroides spp.) were from species that were isolated from feces. However, ruminants secrete copious saliva and the presence of animal glycan-degrading enzymes in rumen Prevotella spp. may enable them to utilize salivary N-linked glycoproteins29, and help explain their abundance in the rumen microbiome22.

The multisubunit cellulosome is an alternative strategy for complex glycan breakdown in which a small module (dockerin) appended to glycan-cleaving enzymes anchors various catalytic units onto cognate cohesin repeats found on a large scaffolding protein30. Cellulosomes have been reported in only a small number of species, mainly in the family Ruminococcaceae in the order Clostridiales. Supplementary Table 4 reports the number of dockerin and cohesin modules found in the reference genomes and the main cellulosomal bacteria are highlighted in Supplementary Figure 2. We find that Clostridiales bacteria can be divided into four broad categories: (i) those that have neither dockerins nor cohesins (non-cellulosomal species), (ii) those that have just a few dockerins and no cohesins (most likely non-cellulosomal), (iii) those that have a large number of dockerins and many cohesins (true cellulosomal bacteria like Ruminococcus flavefaciens) and (iv) those that have a large number of dockerins but just a few cohesins like R. albus and R. bromii. In R. albus, it is likely that a single cohesin serves to anchor isolated dockerin-bearing enzymes onto the cell surface rather than to build a bona fide cellulosome. The starch-degrading enzymes of R. bromii bear dockerin domains that enable them to assemble into cohesin-based amylosomes31, analogous to cellulosomes, which are active against particulate resistant starches. R. bromii strains from the human gut microbiota and the rumen encode similar enzyme complements31.

Fermentation pathways.

Most of what is known about microbial fermentation pathways in the rumen has been derived from measurements of end product fluxes or inferred from pure or mixed cultures of microorganisms in vitro, and based on reference metabolic pathways present in non-rumen microbes. The relative participation of particular species in each pathway, or their contribution to end product formation in vivo, is poorly characterized. To determine the functional potential of the sequenced species, we used genome information in combination with the published literature to assign bacteria to different metabolic strategies, on the basis of their substrate utilization and production of specific fermentation end products (Supplementary Table 5). The main metabolic pathways and strategies are present in at least one of, or combinations of, the most abundant bacterial and archaeal groups found in the rumen (Fig. 2b); as a result, we now have a better understanding of which pathways are encoded by these groups. The analysis also provides the first information on the contribution made by the abundant but uncharacterized members of the orders Bacteroidales and Clostridiales to the rumen fermentation. This metabolic scheme provides a framework for the investigation of gene function in these organisms, and the design of strategies that may enable manipulation of rumen fermentation.

Gene loss.

One curious feature of several rumen bacteria is the absence of an identifiable enolase, the penultimate enzymatic step in glycolysis, which is conserved in all domains of life. Examination of >30,000 isolates from the Integrated Microbial Genomes with Microbiomes (IMG/M) database32 revealed that enolase-negative strains were rare (<0.5% of total), and that a high proportion of such strains were rumen isolates belonging to the genera Butyrivibrio and Prevotella and uncharacterized members of the family Lachnospiraceae (Supplementary Table 5). In the genus Butyrivibrio approximately half the sequenced strains lack enolase, while some show a truncated form. The distribution of this enzyme in relation to the phylogeny of this genus is shown in Figure 3. This analysis suggests that enolase is in the process of being lost by some rumen Butyrivibrio isolates and that we may be observing an example of environment-specific evolution by gene loss33. Although the adaptive advantage conferred by loss of enolase is not clear, there is a possible link with pyruvate metabolism and lactate production. Several enolase-negative Butyrivibrio strains do not produce lactate and 12 also lack the gene for L-lactate dehydrogenase. Conversely the enolase and L-lactate dehydrogenase genes are co-located in seven strains. An attempt to identify additional functions exhibiting a similar pattern of gene loss (or a complementing gain of function) by comparing enolase-positive versus enolase-negative Butyrivibrio spp. strains yielded no substantial additional insights (Supplementary Table 6).

Maximum likelihood tree based on concatenated alignment of 56 conserved marker proteins from genomes of all Butyrivibrio strains in the Hungate Collection. Strains lacking a detectable enolase gene are indicated by pale pink shading while those with a truncated enolase are indicated by lavender shading. Strains without shading possess an intact enolase.

Another example of gene loss is seen in bacteria that have lost their complete glycogen synthesis and utilization pathway, as shown by the concomitant loss of families GH13, GH77, GT3 or GT5, and GT35 (Supplementary Fig. 2). These bacteria include nutritionally fastidious members of the Firmicutes (Allisonella histaminiformans, Denitrobacterium detoxificans, Oxobacter pfennigii) and Proteobacteria (Wolinella succinogenes), and have also lost most of their degradative CAZymes, suggesting that they have evolved toward a downstream position as secondary fermenters where they feed on fermentation products (acetate, pyruvate, amino acids) from primary degraders.

Biosynthetic gene clusters.

We searched the Hungate genomes for biosynthetic gene clusters (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 7) to identify evidence of secondary metabolites that might be used as rumen modifiers to reduce methane production through their antimicrobial activity34. A total of 6,906 biosynthetic clusters were predicted from the Hungate genomes (Supplementary Note 2).

CRISPRs.

Identification of CRISPR–Cas systems and their homologous protospacers from viral, plasmid and microbial genomes could shed light on past encounters with foreign mobile genetic elements35 and somewhat indirectly, habitat distribution and ecological interactions36. A total of 6,344 CRISPR spacer sequences were predicted from 241 Hungate genomes and searched against various databases (Supplementary Table 8). Searching spacers against a database of cultured and uncultured DNA viruses and retroviruses (IMG/VR) revealed novel associations between 83 viral operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and 31 Hungate hosts. The vast majority of these viruses were derived from human intestinal and ruminal samples. Details and additional results are furnished in Supplementary Note 3.

Metagenomic sequence recruitment

We evaluated whether the Hungate catalog can contribute to metagenomic analyses by using a total of 1,468,357 coding sequences (CDSs) from the 501 reference genomes to search against ∼1.9 billion CDS predicted from more than 8,200 metagenomic data sets from diverse habitats. A total of 892,995 Hungate CDSs (∼60%) were hits to 13,364,644 metagenome proteins at ≥ 90% amino acid identity. 466 out of 501 Hungate isolates recruited sequences from 2,219 metagenomic data sets derived from host-associated, environmental or engineered sources (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 9). The large number of human samples recruited (1,699) can be attributed to the greater availability of human samples compared to metagenomes from other mammals, including ruminants. Considering the number of isolate CDSs with hits to metagenome sequences (% coverage), most Hungate genomes (413/501) are represented in rumen metagenome samples, as well as in human or other vertebrate samples (Fig. 4). The average % coverage for 466 recruited genomes was 26.5% of total CDS, with Sharpea azabuensis DSM 18934 showing the highest capture (95.6%) in a sheep rumen metagenome (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Maximum likelihood tree based on 16S rDNA gene alignment of rumen strains. The tree clades are color coded according to phylum. Multi-bar-chart depicting the average % coverage of total CDS of an isolate by metagenome samples from each ecosystem category was drawn using iTOL55. Dashed boxes highlight interesting examples of recruitment such as isolates detected in both rumen and human samples (maroon boxes) or detected in human but not rumen samples (red boxes), and others. Number key is as follows (average % coverage is given in parentheses): 1. Sharpea azabuensis str. (∼88%), Kandleria vitulina str. (∼87%); 2. Staphylococcus epidermidis str. (∼40%), Lactobacillus ruminis str. (∼51%); 3. Streptococcus equinus str. (∼38% by rumen, ∼35% by human); 4. Prevotella bryantii str. (∼38% by rumen, ∼9% by human); 5. Bacteroides spp.(∼38%); 6. Bifidobacterium spp. (∼24%), Propionibacterium acnes (∼39%); 7. Shigella sonnei (∼30% by human), E. coli PA3 (∼31% by human), Citrobacter sp. NLAE-zl-C269 (20% by human); 8. Clostridium beijerinckii HUN142 (87% by plant); 9. Methanobrevibacter spp. (∼32%⋆Figure 4 Maximum likelihood tree based on 16S rDNA gene alignment of rumen strains. The tree clades are color coded according to phylum. Multi-bar-chart depicting the average % coverage of total CDS of an isolate by metagenome samples from each ecosystem category was drawn using iTOL55. Dashed boxes highlight interesting examples of recruitment such as isolates detected in both rumen and human samples (maroon boxes) or detected in human but not rumen samples (red boxes), and others. Number key is as follows (average % coverage is given in parentheses): 1. Sharpea azabuensis str. (~88%), Kandleria vitulina str. (~87%); 2. Staphylococcus epidermidis str. (~40%), Lactobacillus ruminis str. (~51%); 3. Streptococcus equinus str. (~38% by rumen, ~35% by human); 4. Prevotella bryantii str. (~38% by rumen, ~9% by human); 5. Bacteroides spp.(~38%); 6. Bifidobacterium spp. (~24%), Propionibacterium acnes (~39%); 7. Shigella sonnei (~30% by human), E. coli PA3 (~31% by human), Citrobacter sp. NLAE-zl-C269 (20% by human); 8. Clostridium beijerinckii HUN142 (87% by plant); 9. Methanobrevibacter spp. (~32%). The innermost circle identifies Hungate isolates of fecal (★) or salivary (♦) origin. Please refer to Supplementary Table 9 for data and other specifics.

Examining recruitment against available rumen metagenomes, a majority of 336 isolates were captured in 24 rumen samples (27% average coverage) (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 9). A further 52 rumen isolates may be included if the hit count recruitment parameter is relaxed from 200 to 50. These isolates are predicted to occur in relatively low abundance in these rumen metagenomes, and raise the proportion of recruiters to almost 80% of the total Hungate catalog. Top recruitment (in terms of % coverage of total isolate CDS) was by organisms previously identified as dominant genera in the rumen10,22,37,38, such as Prevotella spp., Ruminococcus spp., Butyrivibrio spp. and members of the unnamed RC-9, R-7 and R-25 groups. Some Hungate catalog genomes were exclusively detected in one or a few samples originating from the same ruminant host (e.g., sheep-associated Sharpea, Kandleria and Megasphaera strains), whereas others were detected across all ruminants (e.g., Prevotella spp.). It is, however, important to acknowledge the limitations of existing rumen metagenome samples (not merely in terms of their paucity), as they were sourced from animals on special diets (e.g., switchgrass5 or lucerne (alfalfa) pellets39), which may alter the microbiome22.

165 Hungate cultures were not detected in deposited rumen metagenome data sets under the thresholds applied. Many of these (∼50) were of fecal origin, and reflect how the microbiota of the rumen is distinct from that found in other regions of the ruminant GI tract40.

A total of 68 isolates were recruited by both rumen and human intestinal samples and represent shared species between the rumen and human microbiomes (Fig. 4), possibly fulfilling similar roles. A further 66 Hungate isolates were recruited by human samples but were not detected in rumen samples, giving a total of 134 Hungate catalog genomes that recruited various human samples, making them valuable reference sequences for the analysis of human microbiome samples. This observation is also indirectly recapitulated by the CRISPR–CAS systems-based analysis, which showed links to spacers from human intestinal samples, particularly for Hungate isolates of fecal origin (Supplementary Table 8). Additional metagenome recruitment analysis details are provided in Supplementary Note 4.

Comparison with human gut microbiota

Many Hungate strains (134/501) were shared between rumen and human intestinal microbiome samples. This is unsurprising, as both habitats are high-density, complex anaerobic microbial communities, producing similar fermentation products, and with extensive interspecies cross-feeding and interaction41. We performed a comparative analysis against available human intestinal isolates (largely from the HMP), to identify differences that can be attributed to distinct lifestyles and adaptive capacity of rumen microorganisms. The Hungate and human intestine isolate collections were curated to remove redundancy, low-quality genomes and known human pathogens. This resulted in a set of 458 rumen and 387 human intestinal genomes (Supplementary Table 10), which was used to identify protein families in the Pfam database that were differentially abundant in isolates from each environment. Out of 7,718 Pfam domains found in 458 non-redundant Hungate isolate genomes, we determined 367 were over-represented in the ruminal genomes and 423 were under-represented on the basis of the false-discovery rate (FDR), q-value < 0.001 (Supplementary Table 11). Over-represented Pfams (Fig. 5) included enzymes involved in plant cell wall degradation (GH11, GH16, GH26, GH43, GH53, GH67, GH115), carbohydrate-binding modules (CBM2, CBM3, and cohesin and dockerin modules associated with cellulosome assembly) and GT41 family glycosyl transferases, which occur predominantly in the genera Anaerovibrio and Selenomonas. Notably, Pfams for the biosynthesis of cobalamin (vitamin B12, an essential micronutrient for the host, were over-represented. Vitamin B12 biosynthesis is one of the most complex pathways in nature, involving more than 30 enzymatic steps, and given its high metabolic cost, is only encoded by a small set of bacteria and archaea. We examined this biosynthetic pathway in more detail using other functional annotation types (KO and Tigrfam) across the 501 Hungate isolates, and discovered that 12 or more enzymatic steps were overrepresented in the Hungate genomes, and at least 47 isolates might be capable of de novo B12 synthesis (Supplementary Table 12). Many of these were members of the Class Negativicutes within the Firmicutes (Anaerovibrio, Mitsuokella, and Selenomonas). A further 140 (including 21 archaeal) genomes encode enzymes for the salvage of B12 from an intermediate, and may even work cooperatively (based on potential complementarity of lesions in the pathway in different members) to share and synthesize corrinoids for community and/or host benefit. These observations reflect the high burden of a requirement for vitamin B12, which is needed as a cofactor for enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis from propionate in the liver. This process is essential for lactose biosynthesis and milk production in dairy animals42, and dairy and meat products of ruminant origin are important dietary sources of B12 (ref. 43). By contrast, it has been speculated that human gut microbes were unlikely to contribute significant amounts of B12 for their host and were likely competitors for dietary B12 (ref. 44).

Of the Pfams (Fig. 5) under-represented in Hungate genomes, the occurrence of all steps for the oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway (OPPP) was striking. The role of the OPPP is primarily the irreversible production of reducing equivalents (NADPH), although other enzymes may serve as alternate sources of reducing equivalents. As discussed above, the Pfam for enolase appeared in the list of under-represented families. The list also contained several Pfams associated with bacteriophage functions and sporulation. The differential abundance of sporulation genes is interesting as the observation that sporulation genes are abundant in human gut bacteria has been made recently16,31 and is potentially linked with resistance to oxygen exposure. This observation is particularly striking given the preponderance of Firmicutes, an archetypically spore-forming phylum45, in the rumen set. Large and small subunits of an oxygen-dependent Class I type ribonucleotide reductase were also under-represented together with several other Pfams implicated in oxygen tolerance, suggesting that human intestinal isolates may encounter higher oxygen tension compared to the strictly anaerobic ruminal ecosystem. These observations indirectly suggest that host genetics and physiology influence rumen microbiome composition and that rumen microbes are likely to be vertically inherited as indicated in recent studies46,47. Conversely, human intestinal (more specifically, fecal) isolates are transmitted from other sources in the environment31,48. We were able to recapitulate these findings in a metagenome-based comparison of these two environments (sheep rumen samples against normal human fecal samples; Supplementary Table 13), suggesting that these differences cannot be explained by cultivation or abundance biases in the isolate data sets.

Discussion

The Hungate genome catalog that we report here includes genomic analysis of 501 bacterial and archaeal cultures that represent almost all of the cultured rumen species that have been taxonomically characterized, as well as representatives of several novel species and genera. This high-quality reference collection will guide interpretation of metagenomics data sets, including genomes recovered from metagenomes (MAGs). The Hungate genome catalog also allows robust comparative genomic analyses that are not feasible using incomplete sequence data from metagenomes. Researchers have access to Hungate Collection strains, which will enable a better understanding of carbon flow in the rumen, including the breakdown of lignocellulose, through the metabolism of substrates to SCFAs and fermentation end products, to the final step of CH4 formation.

The Hungate genome collection is by no means complete. Some important taxa are missing, especially members of the order Bacteroidales10,22. At the start of this project genome sequences were available for strains belonging to 11 (12.5%) of the 88 genera described for the rumen. Currently, genome sequences are available for 73 (83%) of those 88 genera, as well as for 73 strains that are only identified to the family or order taxonomic level. Of the rumen 'most wanted list' which comprises 70 rumen bacteria10, the Hungate Collection has now contributed 30 members. In addition to missing bacteria and archaea, the sequencing of rumen eukaryotes presents considerable technical challenges and although some progress has been made in sequencing of anaerobic fungi49, there are no genome data for rumen ciliate protozoa, and only preliminary data on the rumen virome50.

Microbiome research is moving from descriptive to mechanistic, and to translation of those mechanisms into interventions51. Using rumen microbiome data to engineer rumens to reduce CH4 emissions52 and improve productivity and sustainability outcomes is now in sight53. The Hungate Collection provides a starting point for this, shedding light on what has been described as 'the world's largest commercial fermentation process'54. Future studies can use the Hungate resources to improve the resolution of rumen meta-omics analyses, to identify antimicrobials, to source carbohydrate-degrading enzymes from the rumen for use as animal feed additives and in lignocellulose-based biofuel generation, and as the basis for synthetic microbial consortia.

Methods

Cultures used in this study.

The full list of cultures used in the project and their provenance is shown in Supplementary Table 1 with additional information available in Supplementary Note 1. New Zealand bacterial cultures from the Hungate Collection are available from the AgResearch culture collection while other cultures should be obtained from the relevant culture collections or requested from the sources shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Genomic DNA isolation.

Genomic DNA was extracted using the Qiagen Genomic-tip kit following the manufacturer's instructions for the 500/G size extraction. Purified DNA was subject to partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing to confirm strain identity, before being shipped to the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI), USA for sequencing.

Sequence, assembly and annotation.

All Hungate genomes were sequenced at the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI) using Illumina technology56 or Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) RS technology57. For all genomes, we either constructed and sequenced an Illumina short-insert paired-end library with an average insert size of 270 bp, or a Pacbio SMRTbell library. Genomes were assembled using Velvet58, ALLPATHS59 or Hierarchical Genome Assembly Process (HGAP)60 assembly methods (specifics provided in Supplementary Table 2). Genomes were annotated by the DOE–JGI genome annotation pipeline61,62. Briefly, protein-coding genes (CDSs) were identified using Prodigal63 followed by a round of automated and manual curation using the JGI GenePrimp pipeline64. Functional annotation and additional analyses were performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG-ER) platform32. All data as well as detailed sequencing and assembly reports can be downloaded from https://genome.jgi.doe.gov/portal/pages/dynamicOrganismDownload.jsf?organism=HungateCollection.

Hungate Collection and the Global Rumen Census analysis.

We used the 16S rRNA gene sequences generated from the Global Rumen Census (GRC)22 to map the phylogenetic positions of the Hungate Collection genomes onto the known global distribution of Bacteria and Archaea from the rumen. Ten-thousand predicted OTUs were randomly chosen from the total 673,507 OTUs identified from that study in order to construct a phylogenetic tree. The 16S rRNA gene sequences for Hungate Collection genomes were added to the GRC subsample, and all Bacteria and Archaea were checked for chimeras and to ensure they represented separate OTUs using CDHIT-OTU65 (with a 0.97% identity Ribosomal Database Project (RDP)66 followed by visual inspection with JalView67. Taxonomic classifications were taken from those predicted by the GRC study. A maximum likelihood tree was then separately constructed for the Bacteria and Archaea using two rounds of Fasttree (version 2.1.7)68: the first round built a maximum likelihood tree using the GTR model of evolution and (options: -gtr –nt); the second round optimized the branch lengths for the resulting topology (options: -gtr -nt -nome –mllen). The resulting phylogenetic trees were visualized using iTOL55 with the mapped positions of the Hungate genomes.

Carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes).

For each of the 501 genomes, the protein sequences were subjected to parallel (i) BLAST queries against CAZy libraries, of both complete sequences and individual modules; and (ii) HMMER searches using CAZy libraries of module family and subfamilies. Family assignments and overall CAZyme modularity were further validated through a human curation step, when proteins were not fully aligned (without gaps) with >50% identity to CAZy records.

Conserved single-copy gene phylogeny.

A set of 56 universally conserved single-copy proteins in bacteria and archaea69 was used for construction of the Butyrivibrio phylogenetic tree. Marker genes were detected and aligned using hmmsearch and hmmalign included in HMMER3 (ref. 70) using HMM profiles obtained from Phylosift71. Alignments were concatenated and filtered. A phylogenetic tree was inferred using the maximum likelihood methods with RAxML (version 7.6.3). Tree topologies were tested for robustness using 100 bootstrap replicates and the standard LG model. Trees were visualized using FastTree followed by iTOL55.

Prediction of biosynthetic clusters.

Putative biosynthetic clusters (BCs) were predicted and annotated using AntiSMASH version 3.0.4 (ref. 72) with the “inclusive” and the “borderpredict” options. All other options were left as default.

CRISPR–CAS system analysis.

A modified version of the Crispr Recognition Tool (CRT) algorithm61, with annotations from the Integrated Microbial Genomes with Metagenomes (IMG/M) system32 was used to validate the functionality of the CRISPR–Cas types (only complete cas gene arrangements were used plus those cas 'orphan' arrays with the same repeat from a complete array within the same genome). This Hungate spacer collection was queried against the viral database from the Integrated Microbial Genome system (IMG/VR database)73, a custom global “spacerome” (predicted from all IMG isolate and metagenome data sets) and the NBCI refseq plasmid database. All spacer searches were performed using the BLASTn-short function from the BLAST+ package74 with parameters: e-value threshold of 1.0 × 10−6, percentage identity of >94% and coverage of >95%. These cutoffs were recommended by a recent study benchmarking the accuracy of spacer hits across a range of % identities and coverage75.

Recruitment of metagenomic sequences.

1,468,357 protein coding sequences or CDS from 501 Hungate isolate genomes were searched using LAST76 against ∼1.9 billion CDS predicted from 8,200 metagenomic samples stored in the IMG database. Hungate genomes were designated as “recruiters” if the following criteria were met: a minimum of 200 CDS with hits at ≥ 90% amino acid identity over 70% alignment lengths to an individual metagenomic CDS or ≥ 10% capture of total CDS in each genome. The rationale for choosing the minimum 200 hit count was to ensure that the evidence included more than merely housekeeping genes (which tend to be more highly conserved). In a few instances, the 200 CDS hit count requirement was relaxed if at least 10% of the total CDS in the genomes was captured. The 90% amino acid identity cutoff was chosen based on Luo et al.77, who assert that organisms grouped at the 'species' level typically show >85% AAI among themselves. We ascertained that ≥ 90% identity was sufficiently discriminatory for species in the Hungate genome set by observing differences in the recruitment pattern (hit count or % CDS coverage) of different species of the same genus (e.g., Prevotella spp., Butyrivibrio spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Treponema spp.) from every phylum against the same metagenomic sample.

For nucleotide read recruitment, total reads from an individual metagenome were aligned against scaffolds from each of the 501 isolates using the BWA aligner78. The effective minimum nucleotide % identity was ∼75% with a minimum alignment length of 50 bp. Alignment results were examined in terms of total number of reads recruited to an isolate (at different % identity cutoffs with ≥ 97% identity proposed as a species-level recruitment), average read depth of total reads recruited to a given isolate genome, as well as % coverage of total nucleotide length of the genome.

Genome comparisons.

For rumen versus human isolates comparisons, human intestinal isolate genomes were carefully selected from the IMG database using available GOLD metadata fields pertaining to isolation source (and taking care to remove known pathogens). Genome redundancies within either the human set or the rumen set were eliminated after assessing the average nucleotide identity (ANI) of total best bidirectional hits and removing genomes sharing >99% ANI (alignment fraction of total CDS ≥ 60%) to another genome within that set. Furthermore, low-quality genomes within the human set were flagged and removed based on the absence of the “high-quality” filter assigned by the IMG quality control pipeline owing to lack of phylum-level taxonomic assignment or if the coding density was <70% or >100% or the number of genes per million base pairs was <300 or >1,200 (ref. 61). This approach resulted in 388 genomes delineated in the human set and 458 genomes in the rumen set (lists provided in Supplementary Table 10). Both collections of genomes had similar average genome sizes (3.3–3.5 Mbp) and completeness (evaluated by CheckM19). Pairwise comparisons of gene counts for individual Pfams between members of each set were performed using Metastats79, which employs a non-parametric two-sided t-test test (or a Fischer's exact test for sparse counts) with false-discovery rate (FDR) error correction to identify differentially abundant features between the two genome sets. Most significant features were delineated using a q-value cutoff of <0.001, and less populous or sparsely recruited Pfams were also eliminated (where the sum of gene counts in each genome set was <100) (Supplementary Table 11, worksheet designated “Q-val<0.001_edited”). A second worksheet labeled “Q-val<0.005” shows a larger subset of differentially abundant Pfams applying the less stringent threshold of Q-value < 0.005, and including results for Pfams with sparse counts. Pfam was chosen for this primary analysis because it is the largest and most widely used source of manually curated protein families, with nearly 80% coverage (on average) of total CDS in these microbial genomes. KO terms or TIGRFAMS were also assessed to validate and complement Pfam-based findings or to examine specific pathways more closely. For comparisons of enolase-positive versus enolase-negative Butyrivibrio spp. strains, Metastats79 was employed in conjunction with contrasting upper and lower quartile or percentile gene counts, in order to identify additional functions with a similar pattern of preservation/loss as the glycolytic enolase gene.

For metagenomes-based comparisons, previously published sheep rumen (IMG IDs: 3300021254, 300021255, 3300021256, 3300021387, 3300021399, 3300021400, 3300021426, 3300021431) and human intestinal (IMG IDs: 3300008260, 3300008496, 3300007299, 3300007296, 3300008272, 3300007361, 3300008551, 3300007305, 3300007717) metagenomes were reassembled using metaSPAdes80, annotated and loaded into IMG. Estimated gene copy numbers (calculated by multiplying gene count with read depth for the scaffold the gene resides on) were compared using Metastats (as described above).

Statistical analysis.

Refer to the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Further information on experimental design is available in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Data availability.

All available genomic data and annotations are available through the IMG portal (https://img.jgi.doe.gov/). Additionally, a dedicated portal to download all 410 genomes sequenced in this study is provided: https://genome.jgi.doe.gov/portal/pages/dynamicOrganismDownload.jsf?organism=HungateCollection.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Godfray, H.C. et al. Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327, 812–818 (2010).

Eisler, M.C. et al. Agriculture: steps to sustainable livestock. Nature 507, 32–34 (2014).

Herrero, M. et al. Biomass use, production, feed efficiencies, and greenhouse gas emissions from global livestock systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 20888–20893 (2013).

Morgavi, D.P., Kelly, W.J., Janssen, P.H. & Attwood, G.T. Rumen microbial (meta)genomics and its application to ruminant production. Animal 7 (Suppl. 1), 184–201 (2013).

Hess, M. et al. Metagenomic discovery of biomass-degrading genes and genomes from cow rumen. Science 331, 463–467 (2011).

Reisinger, A. & Clark, H. How much do direct livestock emissions actually contribute to global warming? Glob. Change Biol. (2017).

Wollenberg, E. et al. Reducing emissions from agriculture to meet the 2 °C target. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 3859–3864 (2016).

Bryant, M.P. Bacterial species of the rumen. Bacteriol. Rev. 23, 125–153 (1959).

Hungate, R.E. The Rumen and Its Microbes (Academic Press, New York, USA, 1966).

Creevey, C.J., Kelly, W.J., Henderson, G. & Leahy, S.C. Determining the culturability of the rumen bacterial microbiome. Microb. Biotechnol. 7, 467–479 (2014).

Nelson, K.E. et al. A catalog of reference genomes from the human microbiome. Science 328, 994–999 (2010).

Mukherjee, S. et al. 1,003 reference genomes of bacterial and archaeal isolates expand coverage of the tree of life. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 676–683 (2017).

Blaser, M.J. et al. Toward a predictive understanding of Earth's microbiomes to address 21st century challenges. MBio 7, e00714–e00716 (2016).

Kyrpides, N.C., Eloe-Fadrosh, E.A. & Ivanova, N.N. Microbiome data science: understanding our microbial planet. Trends Microbiol. 24, 425–427 (2016).

Noel, S. Cultivation and Community Composition Analysis of Plant-Adherent Rumen Bacteria PhD thesis, Massey Univ., N.Z. (2013).

Browne, H.P. et al. Culturing of 'unculturable' human microbiota reveals novel taxa and extensive sporulation. Nature 533, 543–546 (2016).

Lagkouvardos, I. et al. The Mouse Intestinal Bacterial Collection (miBC) provides host-specific insight into cultured diversity and functional potential of the gut microbiota. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16131 (2016).

Mukherjee, S. et al. Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) v.6: data updates and feature enhancements. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 D1, D446–D456 (2017).

Parks, D.H., Imelfort, M., Skennerton, C.T., Hugenholtz, P. & Tyson, G.W. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25, 1043–1055 (2015).

Chain, P.S.G. et al. Genome project standards in a new era of sequencing. Science 326, 236–237 (2009).

Kim, M., Morrison, M. & Yu, Z. Status of the phylogenetic diversity census of ruminal microbiomes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 76, 49–63 (2011).

Henderson, G. et al. Rumen microbial community composition varies with diet and host, but a core microbiome is found across a wide geographical range. Sci. Rep. 5, 14567 (2015).

Harmon, D.L., Yamka, R.M. & Elam, N.A. Factors affecting intestinal starch digestion in ruminants: A review. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 84, 309–318 (2004).

Wen, Y. & Irwin, D.M. Mosaic evolution of ruminant stomach lysozyme genes. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 13, 474–482 (1999).

Domínguez-Bello, M.G. et al. Resistance of rumen bacteria murein to bovine gastric lysozyme. BMC Ecol. 4, 7 (2004).

Lombard, V., Golaconda Ramulu, H., Drula, E., Coutinho, P.M. & Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D490–D495 (2014).

Terrapon, N. et al. PULDB: the expanded database of Polysaccharide Utilization Loci. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 D1, D677–D683 (2018).

Ndeh, D. et al. Complex pectin metabolism by gut bacteria reveals novel catalytic functions. Nature 544, 65–70 (2017).

Ang, C.-S. et al. Global survey of the bovine salivary proteome: integrating multidimensional prefractionation, targeted, and glycocapture strategies. J. Proteome Res. 10, 5059–5069 (2011).

Artzi, L., Bayer, E.A. & Moraïs, S. Cellulosomes: bacterial nanomachines for dismantling plant polysaccharides. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 83–95 (2017).

Mukhopadhya, I. et al. Sporulation capability and amylosome conservation among diverse human colonic and rumen isolates of the keystone starch-degrader Ruminococcus bromii. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 324–336 (2018).

Chen, I.A. et al. IMG/M: integrated genome and metagenome comparative data analysis system. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 D1, D507–D516 (2017).

Albalat, R. & Cañestro, C. Evolution by gene loss. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 379–391 (2016).

Knapp, J.R., Laur, G.L., Vadas, P.A., Weiss, W.P. & Tricarico, J.M. Invited review: Enteric methane in dairy cattle production: quantifying the opportunities and impact of reducing emissions. J. Dairy Sci. 97, 3231–3261 (2014).

Shmakov, S.A. et al. The CRISPR spacer space is dominated by sequences from species-specific mobilomes. MBio 8, e01397–e17 (2017).

Paez-Espino, D. et al. Uncovering Earth's virome. Nature 536, 425–430 (2016).

Jami, E. & Mizrahi, I. Composition and similarity of bovine rumen microbiota across individual animals. PLoS One 7, e33306 (2012).

Lima, F.S. et al. Prepartum and postpartum rumen fluid microbiomes: characterization and correlation with production traits in dairy cows. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 1327–1337 (2015).

Kamke, J. et al. Rumen metagenome and metatranscriptome analyses of low methane yield sheep reveals a Sharpea-enriched microbiome characterised by lactic acid formation and utilisation. Microbiome 4, 56 (2016).

Kim, M. & Wells, J.E. A meta-analysis of bacterial diversity in the feces of cattle. Curr. Microbiol. 72, 145–151 (2016).

Dolfing, J. & Gottschal, J.C. in Gastrointestinal Microbiology Vol. 2 (eds. Mackie, R.I. White, B.A. & Issacson, R.E.) 373–433 (Chapman and Hall, New York. USA, 1997).

Aschenbach, J.R., Kristensen, N.B., Donkin, S.S., Hammon, H.M. & Penner, G.B. Gluconeogenesis in dairy cows: the secret of making sweet milk from sour dough. IUBMB Life 62, 869–877 (2010).

Gille, D. & Schmid, A. Vitamin B12 in meat and dairy products. Nutr. Rev. 73, 106–115 (2015).

Degnan, P.H., Taga, M.E. & Goodman, A.L. Vitamin B12 as a modulator of gut microbial ecology. Cell Metab. 20, 769–778 (2014).

Hutchison, E.A., Miller, D.A. & Angert, E.R. Sporulation in bacteria: beyond the standard model. Microbiol. Spectr. 2 TBS-0013, 2012 (2014).

Roehe, R. et al. Bovine host genetic variation influences rumen microbial methane production with best selection criterion for low methane emitting and efficiently feed converting hosts based on metagenomic gene abundance. PLoS Genet. 12, e1005846 (2016).

Sasson, G. et al. Heritable bovine rumen bacteria are phylogenetically related and correlated with the cow's capacity to harvest energy from its feed. MBio 8, e00703–e00717 (2017).

Nayfach, S., Rodriguez-Mueller, B., Garud, N. & Pollard, K.S. An integrated metagenomics pipeline for strain profiling reveals novel patterns of bacterial transmission and biogeography. Genome Res. 26, 1612–1625 (2016).

Solomon, K.V. et al. Early-branching gut fungi possess a large, comprehensive array of biomass-degrading enzymes. Science 351, 1192–1195 (2016).

Ross, E.M., Petrovski, S., Moate, P.J. & Hayes, B.J. Metagenomics of rumen bacteriophage from thirteen lactating dairy cattle. BMC Microbiol. 13, 242 (2013).

Brüssow, H. Biome engineering-2020. Microb. Biotechnol. 9, 553–563 (2016).

McAllister, T.A. et al. Ruminant Nutrition Symposium: use of genomics and transcriptomics to identify strategies to lower ruminal methanogenesis. J. Anim. Sci. 93, 1431–1449 (2015).

Firkins, J.L. & Yu, Z. Ruminant Nutrition Symposium: how to use data on the rumen microbiome to improve our understanding of ruminant nutrition. J. Anim. Sci. 93, 1450–1470 (2015).

Weimer, P.J. Cellulose degradation by ruminal microorganisms. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 12, 189–223 (1992).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 W1, W242–W245 (2016).

Mavromatis, K. et al. The fast changing landscape of sequencing technologies and their impact on microbial genome assemblies and annotation. PLoS One 7, e48837 (2012).

Eid, J. et al. Real-time DNA sequencing from single polymerase molecules. Science 323, 133–138 (2009).

Zerbino, D.R. & Birney, E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18, 821–829 (2008).

Butler, J. et al. ALLPATHS: de novo assembly of whole-genome shotgun microreads. Genome Res. 18, 810–820 (2008).

Chin, C.-S. et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat. Methods 10, 563–569 (2013).

Huntemann, M. et al. The standard operating procedure of the DOE-JGI Metagenome Annotation Pipeline (MAP v.4). Stand. Genomic Sci. 11, 17 (2016).

Tripp, H.J. et al. Toward a standard in structural genome annotation for prokaryotes. Stand. Genomic Sci. 10, 45 (2015).

Hyatt, D. et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 119 (2010).

Pati, A. et al. GenePRIMP: a gene prediction improvement pipeline for prokaryotic genomes. Nat. Methods 7, 455–457 (2010).

Li, W., Fu, L., Niu, B., Wu, S. & Wooley, J. Ultrafast clustering algorithms for metagenomic sequence analysis. Brief. Bioinform. 13, 656–668 (2012).

Cole, J.R. et al. Ribosomal Database Project: data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D633–D642 (2014).

Clamp, M., Cuff, J., Searle, S.M. & Barton, G.J. The Jalview Java alignment editor. Bioinformatics 20, 426–427 (2004).

Price, M.N., Dehal, P.S. & Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2--approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One 5, e9490 (2010).

Eloe-Fadrosh, E.A. et al. Global metagenomic survey reveals a new bacterial candidate phylum in geothermal springs. Nat. Commun. 7, 10476 (2016).

Mistry, J., Finn, R.D., Eddy, S.R., Bateman, A. & Punta, M. Challenges in homology search: HMMER3 and convergent evolution of coiled-coil regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e121 (2013).

Darling, A.E. et al. PhyloSift: phylogenetic analysis of genomes and metagenomes. PeerJ 2, e243 (2014).

Weber, T. et al. antiSMASH 3.0-a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 W1, W237–W243 (2015).

Paez-Espino, D. et al. IMG/VR: a database of cultured and uncultured DNA viruses and retroviruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 D1, D457–D465 (2017).

Altschul, S.F. et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 (1997).

Edwards, R.A., McNair, K., Faust, K., Raes, J. & Dutilh, B.E. Computational approaches to predict bacteriophage-host relationships. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 40, 258–272 (2016).

Kiełbasa, S.M., Wan, R., Sato, K., Horton, P. & Frith, M.C. Adaptive seeds tame genomic sequence comparison. Genome Res. 21, 487–493 (2011).

Luo, C., Rodriguez-R, L.M. & Konstantinidis, K.T. MyTaxa: an advanced taxonomic classifier for genomic and metagenomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, e73 (2014).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26, 589–595 (2010).

White, J.R., Nagarajan, N. & Pop, M. Statistical methods for detecting differentially abundant features in clinical metagenomic samples. PLOS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000352 (2009).

Nurk, S., Meleshko, D., Korobeynikov, A. & Pevzner, P.A. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 27, 824–834 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The Hungate1000 project was funded by the New Zealand Government in support of the Livestock Research Group of the Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases (http://www.globalresearchalliance.org). The genome sequencing and analysis component of the project was supported by the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (JGI) through their Community Science Program (CSP 612) under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, and used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, which is supported by the Office of Science of the US Department of Energy. This work was also supported in part by a grant to B.H.: European Union's Seventh Framework Program (FP/2007/2013)/European Research Council (ERC) Grant Agreement 322820. We thank all the JGI staff that contributed to this project including T.B.K. Reddy, I. Pagani, E. Lobos, S. Mukherjee, A. Thomas, D. Stamatis and J. Bertsch for metadata curation, C.-L. Wei for sequencing, J. Han, A. Clum, B. Bushnell and A. Copeland for assembly, K. Mavromatis, M. Huntemann, G. Ovchinnikova and N. Mikhailova for annotation and submission to IMG, A. Chen, K. Chu, K. Palaniappan, M. Pillay, J. Huang, E. Szeto, D. Wu and V. Markowitz for additional annotation and integration into IMG, A. Schaumberg, E. Andersen, S. Hua, H. Nordberg, I. Dubchak, S. Wilson, A. Shahab for NCBI registrations and submission to INSDC, L. Goodwin, N. Shapiro and T. Tatum for project management, A. Visel for helpful comments on the manuscript and J. Bristow for supporting the project. We are grateful to J. White of Resphera Biosciences for assistance with using Metastats. We thank L. Olthof and G. Peck for isolating cultures that were included in this work. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the US Department of Agriculture. The project title refers to the pioneering work in culturing strictly anaerobic rumen bacteria carried out by Robert (Bob) E. Hungate, who trained many of New Zealand's first rumen microbiologists.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

S.C.Le, G.T.A., E.R., W.J.K. conceived the project; S.C.Le, G.T.A., A.L.C., W.J.K. designed and managed the project; Hungate1000 project collaborators provided cultures. K.H.T. isolated new cultures; K.H.T., S.C.La, A.L.C., R.P. grew cultures and prepared genomic DNA; R.S., S.C.Le, G.T.A., E.A.E.F., G.A.P., M.H., N.J.V., D.P.E., G.H., C.J.C., N.T., P.L., E.D., V.L., N.C.K., B.H., T.W., N.N.I., W.J.K. analyzed and interpreted the data; S.C.Le, R.S., W.J.K. wrote the manuscript assisted by G.T.A., N.T., B.H., T.W., N.N.I. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Integrated supplementary information

Supplementary Figure 1 Phylum and genome size distribution of the 501 Hungate catalogue genomes.

a) Phylum distribution of the sequenced organisms.

b) Genome size distribution in the different phyla of sequenced organisms.

Supplementary Figure 2 Carbohydrate degradative capabilities of the 501 Hungate catalogue genomes.

Family counts of degradative CAZymes (glycoside hydrolases (GHs) and polysaccharide lyases (PLs)), dockerins (DOC) and cohesins (COH) were used to cluster the 501 Hungate genomes. Hierarchical clustering was realized with Spearman’s rank correlation as distance and pairwise average-linkage as clustering method. Phyla with six or less representative species (grouped as "Others") and main taxonomic phyla were distinguished by a colour-code at left. Clusters of CAZyme families involved in the breakdown of selected polysaccharides are coloured at the bottom. Coloured boxes outline specific taxonomic groups that degrade these polysaccharides. Arrows indicate the rare absence of the GH13 starch/glycogen family.

Supplementary Figure 3 The most abundant CAZyme (glycoside hydrolase) families among 501 Hungate catalogue genomes.

Dark green, plant structural carbohydrates (cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin); Light green, plant storage carbohydrates (fructans, raffinose, starch); blue, peptidoglycan.

Supplementary Figure 4 Genomic view of the PUL for rhamnogalacturonan type II breakdown in B. thetaiotaomicron VPI-5482 and microsyntenic regions in the species studied in this work.

Protein-coding genes are depicted by coloured rectangles to highlight the following functional modules: GHs in light pink, PLs in dark pink, HTCS and ECF-σ/anti-σ factor regulators in cyan, MFS and SusC transporters in purple, SusD outer membrane proteins in orange, peptidases in gold, esterases (Ac for acetyl and Me for methyl) in brown. Polygons, coloured according to functional modules, outline the orthologs and reveal likely genomic rearrangements between species. Triangles with dotted-lines indicate specific insertion/deletion between highly similar regions. Genes are represented either above or below a central black line to represent the coding strand. When PUL genes are split across several scaffolds, due to incomplete genome assembly, the scaffold limits are indicated by vertical red bars.

Supplementary Figure 5 Distribution of genes encoding antimicrobial biosynthetic clusters (bacteriocins, lantipeptides and non-ribosomal peptide synthases) in the Hungate catalogue genomes

Maximum likelihood tree based on 16S rDNA gene alignment was visualized and annotated using iTOL. Tree clades are colour coded according to phylum. Multi-bar-charts depict the total number of biosynthetic clusters for putative antimicrobial secondary metabolite classes in each genome.

Supplementary Figure 6 Protein recruitment plot showing amino acid % identity (y-axis) of top hits of Sharpea azabuensis DSM 18934 CDSs against metagenomic sequences from New Zealand sheep rumen samples.

Isolate CDSs are ordered on the x-axis by position on individual scaffolds (which are themselves ordered by descending sequence length) available for this genome.

Supplementary Figure 7 Recruitment of rumen metagenomes by Hungate catalogue genomes.

Maximum likelihood tree based on 16S rDNA gene alignment was visualized and annotated using iTOL. Tree clades are colour coded according to phylum. Bar-charts depict the average % coverage of total CDSs of an isolate by rumen metagenome samples from each ruminant host shown on individual circles around the tree.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–7 (PDF 1301 kb)

Supplementary Table 1

Cultures and their provenance. (XLSX 46 kb)

Supplementary Table 2

Genome statistics for the 410 sequenced bacteria and archaea. (XLSX 66 kb)

Supplementary Table 3

Genome sequencing projects for rumen microbes. (XLSX 14 kb)

Supplementary Table 4

CAZyme analysis. GH, glycoside hydrolases; PL, polysaccharide lyases;∼GT, glycosyl transferases; DOC, dockerins, COH, cohesins; CE, carbohydrate esterases; CBM, carbohydrate-binding modules; AA, auxillary activities. (XLSX 505 kb)

Supplementary Table 5

Metabolic strategies and metabolic pathways encoded by the Hungate catalogue genomes. (XLSX 42 kb)

Supplementary Table 6

List of differentially abundant Pfams in enolase-positive versus enolasenegative strains of Butyrivibrio spp. (XLSX 244 kb)

Supplementary Table 7

Biosynthetic clusters identified in the Hungate catalogue genomes. (XLSX 408 kb)

Supplementary Table 8

Hungate CRISPR spacer search results (XLSX 596 kb)

Supplementary Table 9

Protein recruitment results of rumen isolate CDS by individual metagenomes in IMG. (XLSX 1131 kb)

Supplementary Table 10

List of 458 rumen isolates and 387 human intestinal isolates used for genome comparisons. (XLSX 44 kb)

Supplementary Table 11

List of Pfams that are over-represented (green highlight) or underrepresented (pink highlight) in the ruminal compared to the human intestinal isolate genomes. (XLSX 386 kb)

Supplementary Table 12

Occurrence of vitamin B12 biosynthetic pathway genes in the rumen isolate genomes. Green highlight indicates genomes with predicted de novo biosynthetic capability. (XLSX 89 kb)

Supplementary Table 13

List of Pfams that are over-represented (green highlight) or underrepresented (pink highlight) in the sheep ruminal metagenomes compared to the human intestinal metagenomes. (XLSX 1118 kb)

Rights and permissions

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Seshadri, R., Leahy, S., Attwood, G. et al. Cultivation and sequencing of rumen microbiome members from the Hungate1000 Collection. Nat Biotechnol 36, 359–367 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4110

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4110

This article is cited by

-

Unraveling the phylogenomic diversity of Methanomassiliicoccales and implications for mitigating ruminant methane emissions

Genome Biology (2024)

-

Diet and monensin influence the temporal dynamics of the rumen microbiome in stocker and finishing cattle

Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology (2024)

-

Impact of rumen microbiome on cattle carcass traits

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Enhancing the Conventional Culture: the Evaluation of Several Culture Media and Growth Conditions Improves the Isolation of Ruminal Bacteria

Microbial Ecology (2024)

-

Deep-sea Bacteroidetes from the Mariana Trench specialize in hemicellulose and pectin degradation typically associated with terrestrial systems

Microbiome (2023)