Abstract

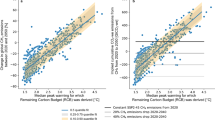

Global temperature targets, such as the widely accepted limit of an increase above pre-industrial temperatures of two degrees Celsius, may fail to communicate the urgency of reducing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. The translation of CO2 emissions into regional- and impact-related climate targets could be more powerful because such targets are more directly aligned with individual national interests. We illustrate this approach using regional changes in extreme temperatures and precipitation. These scale robustly with global temperature across scenarios, and thus with cumulative CO2 emissions. This is particularly relevant for changes in regional extreme temperatures on land, which are much greater than changes in the associated global mean.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker, T. F. et al. ) 3–29 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013). This ‘Summary for Policymakers’ (approved line by line by the IPCC plenary) includes, for the first time, a figure relating cumulative CO 2 emissions with projected changes in global mean temperature (Fig. 1 in this Perspective); it builds upon refs 2–4 and more recent simulations and publications on this topic.

Meinshausen, M. et al. Greenhouse-gas emission targets for limiting global warming to 2 °C. Nature 458, 1158–1162 (2009)

Allen, M. R. et al. Warming caused by cumulative carbon emissions towards the trillionth tonne. Nature 458, 1163–1166 (2009)

Matthews, H. D., Gillett, N. P., Stott, P. A. & Zickfeld, K. The proportionality of global warming to cumulative carbon emissions. Nature 459, 829–832 (2009)

Knutti, R. & Rogelj, J. The legacy of our CO2 emissions: a clash of scientific facts, politics and ethics. Clim. Change 133, 361–373 (2015)

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Persistent growth of CO2 emissions and implications for reaching climate targets. Nature Geosci. 7, 709–715 (2014)

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. in Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation (eds Field, C. B. et al. ) A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 109–230 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012)

Orlowsky, B. & Seneviratne, S. I. Global changes in extreme events: regional and seasonal dimension. Clim. Change 110, 669–696 (2012). This article provides an analysis of the scaling of changes in regional temperature extremes with changes in global warming, as well as its decomposition in several contributing factors (regional, seasonal, and differential response of extremes versus the median).

Lehner, F. & Stocker, T. F. From local perception to global perspective. Nature Clim. Change 5, 731–734 (2015)

Diffenbaugh, N. S. & Ashfaq, M. Intensification of hot extremes in the United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L15701 (2010)

Trenberth, K. E. & Fasullo, J. T. An apparent hiatus in global warming? Earth’s Future 1, 19–32 (2013)

Seneviratne, S. I., Donat, M., Mueller, B. & Alexander, L. V. No pause in the increase of hot temperature extremes. Nature Clim. Change 4, 161–163 (2014)

Victor, D. G. & Kennel, C. F. Climate policy: Ditch the 2 °C warming goal. Nature 514, 30–31 (2014)

Karl, T. R. et al. Possible artifacts of data biases in the recent global surface warming hiatus. Science 348, 1469–1472 (2015)

Sutton, R. T., Dong, B. & Gregory, J. M. Land/sea warming ratio in response to climate change: IPCC AR4 model results and comparison with observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L02701 (2007)

Herger, N., Sanderson, B. M. & Knutti, R. Improved pattern scaling approaches for the use in climate impact studies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 3486–3494 (2015)

Seneviratne, S. I., Lüthi, D., Litschi, M. & Schär, C. Land–atmosphere coupling and climate change in Europe. Nature 443, 205–209 (2006)

Kharin, V. V., Zwiers, F. W., Zhang, X. & Hegerl, G. C. Changes in temperature and precipitation extremes in the IPCC ensemble of global coupled model simulations. J. Clim. 20, 1419–1444 (2007)

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. Impact of soil moisture-climate feedbacks on CMIP5 projections: first results from the GLACE-CMIP5 experiment. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5212–5217 (2013)

Serreze, M. C. & Barry, R. G. Processes and impacts of Arctic amplification. A research synthesis. Glob. Planet. Change 77, 85–96 (2011)

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds The Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R. K. & Meyer, L. A. ) 1–151 (IPCC, 2014)

Council of the European Union. Climate Change and International Security http://register.consilium.europa.eu/doc/srv?l=EN&f=ST%207249%202008%20INIT [accessed 16 November 2015] (2008)

Kelley, C. P., Mohtadi, S., Cane, M. A., Seager, R. & Kushnir, Y. Climate change in the Fertile Crescent and implications of the recent Syrian drought. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 3241–3246 (2015)

Murray, V. et al. in Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation (eds Field, C. B. et al. ) A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 487–542 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012)

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Field, C. B. et al. ) 1–32 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014)

Fischer, E. M., Sedlacek, J., Hawkins, E. & Knutti, R. Models agree on forced response pattern of precipitation and temperature extremes. Geophys. Res. Lett. (2014). This article shows a substantial intermodel agreement of the forced response pattern of precipitation and temperature extremes.

Deser, C., Knutti, R., Solomon, S. & Phillips, A. Communication of the role of natural variability in future North American climate. Nature Clim. Change 2, 775–779 (2012)

Orlowsky, B. & Seneviratne, S. I. Elusive drought: uncertainty in observed trends and short- and long-term CMIP5 projections. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 17, 1765–1781 (2013)

Lenton, T. M. et al. Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 1786–1793 (2008)

Church, J. A. et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker, T. F. et al. ) 1137–1216 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013)

Drijfhout, S. et al. Catalogue of abrupt shifts in Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change climate models . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, E5777–E5786 (2015)

Sutton, R., Suckling, E. & Hawkins, E. What does global mean temperature tell us about local climate? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 373, 20140426 (2015)

Flato, G. et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker, T. F. et al. ) 741–866 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013)

Taylor, C. M., de Jeu, R. A. M., Guichard, F., Harris, P. P. & Dorigo, W. A. Afternoon rain more likely over drier soils. Nature 489, 423–426 (2012)

Mueller, B. & Seneviratne, S. I. Systematic land climate and evapotranspiration biases in CMIP5 simulations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 128–134 (2014)

Masato, G., Hoskins, B. & Woollings, T. Winter and summer Northern Hemisphere blocking in CMIP5 models. J. Clim. 26, 7044–7059 (2013)

Hall, A. & Qu, X. Using the current seasonal cycle to constrain snow albedo feedback in future climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L03502 (2006)

Boisier, J. P., Ciais, P., Ducharne, A. & Guimberteau, M. Projected strengthening of Amazonian dry season by constrained climate model simulations. Nature Clim. Change 5, 656–660 (2015)

Levy, H. II et al. The role of aerosol direct and indirect effects in past and future climate change. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 4521–4532 (2013)

Pitman, A. J. et al. Uncertainties in climate responses to past land cover change: first results from the LUCID intercomparison study. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L14814 (2009)

Luyssaert, S. et al. Land management and land-cover changes have impacts of similar magnitude on surface temperature. Nature Clim. Change 4, 389–393 (2014)

Jeong, S.-J. et al. Effects of double cropping on summer climate of the North China Plain and neighbouring regions. Nature Clim. Change 4, 615–619 (2014)

Wilby, R. L. Constructing climate change scenarios of urban heat island intensity and air quality. Environ. Plann. B 35, 902–919 (2008)

Wei, J., Dirmeyer, P. A., Wisser, D., Bosilovich, M. G. & Mocko, D. M. Where does the irrigation water go? An estimate of the contribution of irrigation to precipitation using MERRA. J. Hydrometeorol. 14, 275–289 (2013)

Degu, A. H. et al. The influence of large dams on surrounding climate and precipitation patterns. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L04405 (2011)

Orlowsky, B., Hoekstra, A. Y., Gudmundsson, L. & Seneviratne, S. I. Today’s virtual water consumption and trade under future water scarcity. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 074007 (2014)

Hunt, A. S. P., Wilby, R. L., Dale, N., Sura, K. & Watkiss, P. Embodied water imports to the UK under climate change. Clim. Res. 59, 89–101 (2014)

Hansen, J. et al. Assessing “dangerous climate change”: required reduction of carbon emissions to protect young people, future generations, and nature. PLoS ONE 8, e81648 (2013)

Tschakert, P. 1.5°C or 2°C: a conduit’s view from the science-policy interface at COP20 in Lima, Peru. Clim. Change Resp. 2, 3 (2015)

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Report on the Structured Expert Dialogue on the 2013–2015 Review (FCCC/SB/2015/INF.1) 1–182, http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/sb/eng/inf01.pdf [accessed 16 November 2015] (UNFCCC, 2015)

Christensen, J. H. et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker, T. F. et al. ) 1217–1308 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013)

Frieler, K., Meinshausen, M., Mengel, M., Braun, N. & Hare, W. A scaling approach to probabilistic assessment of regional climate change. J. Clim. 25, 3117–3144 (2012)

Schewe, J. et al. Multimodel assessment of water scarcity under climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3245–3250 (2014)

Hanewinkel, M., Cullmann, D. A., Schelhaas, M.-J., Nabuurs, G.-J. & Zimmermann, N. E. Climate change may cause severe loss in the economic value of European forest land. Nature Clim. Change 3, 203–207 (2012)

Pal, J. S. & Eltahir, E. A. B. Future temperature in southwest Asia projected to exceed a threshold for human adaptability. Nature Clim. Change http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1038/nclimate2833 (2015)

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J. & Meehl, G. A. An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 485–498 (2012)

Zhang, X. et al. Indices for monitoring changes in extremes based on daily temperature and precipitation data. Wiley Interdisc. Rev. Clim. Change 2, 851–870 (2011)

Sillmann, J., Kharin, V. V., Zhang, X., Zwiers, F. W. & Bronaugh, D. Climate extremes indices in the CMIP5 multimodel ensemble: part 1. Model evaluation in the present climate. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 1716–1733 (2013)

Sillmann, J., Kharin, V. V., Zwiers, F. W., Zhang, X. & Bronaugh, D. Climate extremes indices in the CMIP5 multimodel ensemble: part 2. Future climate projections. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 2473–2493 (2013). This article provides time series of climate extreme indices in CMIP5 projections, which have been used as the basis for the present analyses.

Acknowledgements

S.I.S. acknowledges the European Research Council (ERC) ‘DROUGHT-HEAT’ project funded by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (grant agreement FP7-IDEAS-ERC-617518). A.J.P. and M.G.D. were supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science (grant number CE110001028). M.G.D. was also supported by the ARC (grant number DE150100456). This work contributes to the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) Grand Challenge on Extremes. We acknowledge the WCRP Working Group on Coupled Modelling, which is responsible for CMIP, and we thank the climate modelling groups for producing and making available their model output. For CMIP the US Department of Energy’s Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison provides coordinating support and led development of software infrastructure in partnership with the Global Organization for Earth System Science Portals. We thank N. Maher for help with processing CMIP5 data. The climate extremes indices calculated for the different CMIP5 runs were obtained from the Environment Canada CLIMDEX website (http://www.cccma.ec.gc.ca/data/climdex/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.I.S., M.G.D. and A.J.P. designed the study, following an initial discussion between S.I.S, A.J.P. and R.K. S.I.S. coordinated the conception and writing of the article. M.G.D. performed the analyses. R.L.W. contributed to the interpretation of regional impacts. All authors commented on the manuscript and analyses.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figures 1-8. (PDF 5967 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seneviratne, S., Donat, M., Pitman, A. et al. Allowable CO2 emissions based on regional and impact-related climate targets. Nature 529, 477–483 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16542

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16542

This article is cited by

-

Cu-Based Materials for Enhanced C2+ Product Selectivity in Photo-/Electro-Catalytic CO2 Reduction: Challenges and Prospects

Nano-Micro Letters (2024)

-

Synthesis of Long-chain Paraffins over Bimetallic Na–Fe0.9Mg0.1Ox by Direct CO2 Hydrogenation

Topics in Catalysis (2024)

-

The 2022 Extreme Heatwave in Shanghai, Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River Valley: Combined Influences of Multiscale Variabilities

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences (2024)

-

Manipulating local coordination of copper single atom catalyst enables efficient CO2-to-CH4 conversion

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Exponential increases in high-temperature extremes in North America

Scientific Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.