Abstract

Previously known only from isolated teeth and lower jaw fragments recovered from the Cretaceous and Palaeogene of the Southern Hemisphere, the Gondwanatheria constitute the most poorly known of all major mammaliaform radiations. Here we report the discovery of the first skull material of a gondwanatherian, a complete and well-preserved cranium from Upper Cretaceous strata in Madagascar that we assign to a new genus and species. Phylogenetic analysis strongly supports its placement within Gondwanatheria, which are recognized as monophyletic and closely related to multituberculates, an evolutionarily successful clade of Mesozoic mammals known almost exclusively from the Northern Hemisphere. The new taxon is the largest known mammaliaform from the Mesozoic of Gondwana. Its craniofacial anatomy reveals that it was herbivorous, large-eyed and agile, with well-developed high-frequency hearing and a keen sense of smell. The cranium exhibits a mosaic of primitive and derived features, the disparity of which is extreme and probably reflective of a long evolutionary history in geographic isolation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rogers, R. R. et al. A new, richly fossiliferous member comprised of tidal deposits in the Upper Cretaceous Maevarano Formation, northwestern Madagascar. Cretac. Res. 44, 12–29 (2013)

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., Cifelli, R. L. & Luo, Z.-X. Mammals From the Age of Dinosaurs: Origins, Evolution, and Structure (Columbia Univ. Press, 2004)

Goin, F. J. et al. Persistence of a Mesozoic, non-therian mammalian lineage (Gondwanatheria) in the mid-Paleogene of Patagonia. Naturwissenschaften 99, 449–463 (2012)

v. Koenigswald, W., Goin, F. & Pascual, R. Hypsodonty and enamel microstructure in the Paleocene gondwanatherian mammal Sudamerica ameghinoi. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 44, 263–300 (1999)

Gurovich, Y. Additional specimens of sudamericid (Gondwanatheria) mammals from the early Paleocene of Argentina. Palaeontology 51, 1069–1089 (2008)

Gurovich, Y. & Beck, R. The phylogenetic affinities of the enigmatic mammalian clade Gondwanatheria. J. Mamm. Evol. 16, 25–49 (2009)

Rougier, G. W. Vincelestes neuquenianus Bonaparte (Mammalia, Theria) un Primitivo Mamífero del Cretácico Inferior de la Cuenca Neuquina. PhD thesis, Univ. Buenos Aires. (1993)

Rougier, G. W., Apestiguía, S. & Gaetano, L. C. Highly specialized mammalian skulls from the Late Cretaceous of South America. Nature 479, 98–102 (2011)

Krause, D. W., Prasad, G. V. R., von Koenigswald, W., Sahni, A. & Grine, F. E. Cosmopolitanism among Late Cretaceous Gondwanan mammals. Nature 390, 504–507 (1997)

Krause, D. W. Gondwanatheria and ?Multituberculata (Mammalia) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. Can. J. Earth Sci. 50, 324–340 (2013)

Clark, J. M. & Hopson, J. A. Distinctive mammal-like reptile from Mexico and its bearing on the phylogeny of the Tritylodontidae. Nature 315, 398–400 (1985)

Koyabu, D., Maier, W. & Sánchez-Villagra, M. R. Paleontological and developmental evidence resolve the homology and dual embryonic origin of a mammalian skull bone, the interparietal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 14075–14080 (2012)

Ruf, I., Luo, Z.-X. & Martin, T. Re-investigation of the basicranium of Haldanodon exspectatus (Docodonta, Mammaliaformes). J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 33, 382–400 (2013)

Hu, Y., Meng, J., Wang, Y. & Li, C. Large Mesozoic mammals fed on young dinosaurs. Nature 433, 149–152 (2005)

Butler, P. M. Review of the early allotherian mammals. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 45, 317–342 (2000)

Krause, D. W. Jaw movement, dental function, and diet in the Paleocene multituberculate Ptilodus. Paleobiology 8, 265–281 (1982)

Gambaryan, P. P. & Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. Masticatory musculature of Asian taeniolabidoid multituberculate mammals. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 40, 45–108 (1995)

Krause, D. W., Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. & Bonaparte, J. F. Ferugliotherium Bonaparte, the first known multituberculate from South America. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 12, 351–376 (1992)

Krause, D. W. & Bonaparte, J. F. Superfamily Gondwanatherioidea: a previously unrecognized radiation of multituberculate mammals in South America. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 9379–9383 (1993)

Schultz, A. H. The size of the orbit and of the eye in primates. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 26, 389–408 (1940)

Kay, R. F. & Kirk, E. C. Osteological evidence for the evolution of activity pattern and visual acuity in primates. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 113, 235–262 (2000)

Kirk, E. C. Effects of activity pattern on eye size and orbital aperture size in primates. J. Hum. Evol. 51, 159–170 (2006)

Ritland, S. M. The Allometry of the Vertebrate Eye PhD thesis, Univ. Chicago (1982)

Ross, C. F. & Kirk, E. C. Evolution of eye size and shape in primates. J. Hum. Evol. 52, 294–313 (2007)

Kemp, A. D. & Kirk, E. C. Eye size and visual acuity influence vestibular anatomy in mammals. Anat. Rec. 297, 781–790 (2014)

Olson, E. C. Origin of mammals based upon the cranial morphology of therapsid suborders. Spec. Pap. Geol. Soc. Am. 55, 1–130 (1944)

Hurum, J. H. The inner ear of two Late Cretaceous multituberculate mammals, and its implications for multituberculate hearing. J. Mamm. Evol. 5, 65–93 (1998)

Ekdale, E. G. Comparative anatomy of the bony labyrinth (inner ear) of placental mammals. PLoS ONE 8, e66624 (2013)

Yang, A. & Hullar, T. E. Relationship of semicircular canal size to vestibular-nerve afferent sensitivity in mammals. J. Neurophysiol. 98, 3197–3205 (2007)

Berlin, J. C., Kirk, E. C. & Rowe, T. B. Functional implications of ubiquitous semicircular canal non-orthogonality in mammals. PLoS ONE 8, e79585 (2013)

Luo, Z. X., Ruf, I. & Martin, T. The petrosal and inner ear of the Late Jurassic cladotherian mammal Dryolestes leiriensis and implications for ear evolution in therian mammals. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 166, 433–463 (2012)

Mori, K., Nagao, H. & Yoshihara, Y. The olfactory bulb: coding and processing of odor molecule information. Science 286, 711–715 (1999)

Niimura, Y. Olfactory receptor multigene family in vertebrates: from the viewpoint of evolutionary genomics. Curr. Genomics 13, 103–114 (2012)

Scillato-Yané, G. J. & Pascual, R. Un peculiar Paratheria, Edentata (Mammalia) del Paleoceno de Patagonia. Primeras J. Argent. Paleontol. Vertebr., abstr. 15. (1984)

Scillato-Yané, G. J. & Pascual, R. Un peculiar Xenarthra del Paleoceno medio de Patagonia (Argentina). Su importancia en la sistemática de los Paratheria. Ameghiniana 21, 173–176 (1985)

Gurovich, Y. Bio-evolutionary Aspects of Mesozoic Mammals: Description, Phylogenetic Relationships and Evolution of the Gondwanatheria (Late Cretaceous and Paleocene of Gondwana) PhD thesis, Univ. Buenos Aires (2006)

Pascual, R. & Ortiz-Jaureguizar, E. The Gondwanan and South American episodes: two major and unrelated moments in the history of the South American mammals. J. Mamm. Evol. 14, 75–137 (2007)

Pascual, R., Goin, F. J., Krause, D. W., Ortiz-Jaureguizar, E. & Carlini, A. A. The first gnathic remains of Sudamerica: implications for gondwanathere relationships. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 19, 373–382 (1999)

Rich, T. H. et al. An Australian multituberculate and its palaeobiogeographic implications. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 54, 1–6 (2009)

Ali, J. R. & Krause, D. W. Late Cretaceous bioconnections between Indo-Madagascar and Antarctica: refutation of the Gunnerus Ridge causeway hypothesis. J. Biogeogr. 38, 1855–1872 (2011)

Samonds, K. E. et al. Spatial and temporal arrival patterns of Madagascar’s vertebrate fauna explained by distance, ocean currents, and ancestor type. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 5352–5357 (2012)

Samonds, K. E. et al. Imperfect isolation: factors and filters shaping Madagascar’s extant vertebrate fauna. PLoS ONE 8, e62086 (2013)

Evans, S. E., Jones, M. E. H. & Krause, D. W. A giant frog with South American affinities from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 2951–2956 (2008)

Buckley, G. A., Brochu, C., Krause, D. W. & Pol, D. A pug-nosed crocodyliform from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. Nature 405, 941–944 (2000)

Forster, C. A., Sampson, S. D., Chiappe, L. M. & Krause, D. W. The theropod ancestry of birds: new evidence from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. Science 279, 1915–1919 (1998)

Sampson, S. D. et al. Predatory dinosaur remains from Madagascar: implications for the Cretaceous biogeography of Gondwana. Science 280, 1048–1051 (1998)

Sampson, S. D., Carrano, M. T. & Forster, C. A. A bizarre predatory dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. Nature 409, 504–506 (2001)

Crottini, A. et al. Vertebrate time-tree elucidates the biogeographic pattern of major biotic change around the K-T boundary in Madagascar. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 5358–5363 (2012)

Vidal, N. et al. Blindsnake evolutionary tree reveals long history on Gondwana. Biol. Lett. 6, 558–561 (2010)

Ali, J. R. & Aitchison, J. C. Gondwana to Asia: plate tectonics, paleogeography and the biological connectivity of the Indian sub-continent from the Middle Jurassic through latest Eocene (166–35 Ma). Earth Sci. Rev. 88, 145–166 (2008)

Acknowledgements

We thank the Université d’Antananarivo, the Madagascar Institut pour la Conservation des Ecosystèmes Tropicaux, and the villagers of the Lac Kinkony Study Area for logistical support of fieldwork; various ministries of the Republic of Madagascar for permission to conduct field research; members of the 2010 field research team for their efforts; J. Thostenson and M. Hill of the American Museum of Natural History Microscopy & Imaging Facility, New York, New York, and J. Diehm and B. Ruether of Avonix Imaging, Plymouth, Minnesota, and various members of the Department of Radiology at Stony Brook University for providing expert assistance in computed tomography scanning; L. Betti-Nash for artwork; J. Neville for photography; D. Pulaski for reconstructing the cranium and building the finite element models; Z.-X. Luo, G. Rougier and A. Weil for their reviews of the paper; and the National Geographic Society (8597-09) and the National Science Foundation (EAR-0446488, EAR-1123642) for funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.R.G. prepared the fossil; J.R.G., S.H., W.L.H. and P.M.O. conducted most of the micro-computed tomography digital preparation; L.J.R. and R.R.R. provided geological data; H.A. provided logistical support; J.R.G., S.H., D.W.K., W.v.K., P.M.O., J.B.R. and J.R.W. provided most of the descriptions and comparisons; E.R.D., A.D.K., D.W.K., E.C.K., W.v.K., P.M.O., J.A.S. and J.R.W. conducted various functional and comparative analyses; S.H., D.W.K., E.R.S. and J.R.W. contributed to the phylogenetic analysis; D.W.K. developed the manuscript, with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Vintana sertichi has been assigned the Life Science Identifier (LSID) http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:B21CC5B2-D550-4D78-BA1F-8319EA663785.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Figure 1 Enamel microstructure of Vintana sertichi.

Scanning electron micrograph of transverse section of enamel (sampled from distolingual corner of left MF2) revealing the radial arrangement of prisms (p) separated by well-developed interrow sheets (irs) of interprismatic matrix.

Extended Data Figure 2 Craniofacial and endocranial morphology of Vintana sertichi.

a, Reconstruction of right half of cranium (UA 9972) in medial view showing bony composition; sagittally sectioned elements shaded in grey, endocranial cavity shaded in blue. b, Reconstruction of right half of anterior portion of cranium in medial view showing details of nasal cavity, anterior part of endocranium, and nasopharyngeal canal. Dorsoventral extent of cribriform plate indicated in red. Paranasal lamella of nasoturbinal ridge indicated by six short red arrows pointing to a ridge ventral to tectal lamella. c, Digital reconstruction of mid-sagittal cut-away medial view of right posterior half of cranium based on micro-computed tomography scans. d, Digital reconstruction of lateral view of right posterior half of cranium, based on micro-computed tomography scans (squamosal cut away ventrally, indicated by hatching; basisphenoid and other more medial elements removed to show openings). AS, alisphenoid; BS, basisphenoid; ce, cavum epiptericum; cpl, cribriform plate ridge; cs, crista semicircularis; ep, ectopterygoid process; ethr, ethmoturbinal ridges; fo, foramen ovale; FR, frontal; hf, hypoglossal foramina; iam, internal acoustic meatus; IP, interparietal; jf, jugular foramen; LA, lacrimal; lret 1, lateral root of ethmoturbinal 1; MX, maxilla; nlcg, nasolacrimal canal and groove; nvg, neurovascular grooves; OC, occipital; occ, occipital condyle; opf, optic foramen; opg, optic groove; OS, orbitosphenoid; PA, parietal; PAL, palatine; ?pan, possible pila antotica; PE, petrosal; pmet, pila metoptica; ppr, paroccipital process; pr, promontorium; prof, prootic foramen; PT, pterygoid; ptf, posttemporal foramen; ptl, posterior transverse lamina; RMF3, right third upper molariform tooth; rt, foramen for ramus temporalis; saf, subarcuate fossa; sof, sphenorbital fissure; SQ, squamosal; tlnt, tectal lamella of nasoturbinal ridge; vret 1, vertical root of ethmoturbinal 1.

Extended Data Figure 3 Endocranial and inner ear morphology of Vintana sertichi.

a, Digital reconstruction of mid-sagittal cut-away view of right half of cranium and integrated endocranial cast reconstruction, based on micro-computed tomography scans, to reveal position and orientation of endocast (blue; moderately transparent), right inner ear (magenta; petrosal is rendered as fully transparent), and positions of right cranial nerves (CNs, green). b, Digital reconstruction of right osseous labyrinth and cochlear nerve (cranial nerve VIII), based on micro-computed tomography scans, in medial view. Virtual endocast of osseous labyrinth (translucent), with canal system occupied by cochlear nerve (green) depicted both in situ (lower right) and in identical view but isolated and enlarged (upper left). asc, anterior semicircular canal; cc, crus commune; cn, cochlear nerve (part of cranial nerve VIII); “CN” II, optic nerve; CN V3, mandibular division of trigeminal nerve; CN VII, facial nerve; CN VIII, vestibulocochlear nerve; CN IX, glossopharyngeal nerve; CN X, vagus nerve; CN XII, hypoglossal nerve bundles (XIIa and XIIb); hp, habenulae perforatae; lsc, lateral semicircular canal; pf, perilymphatic foramen; psc, posterior semicircular canal; Rc, Rosenthal’s canal (cochlear ganglion canal); scc, secondary crus commune; sl, secondary osseous lamina of cochlea; tf, tractus foraminosus.

Extended Data Figure 4 Composition and features of basicranium of Vintana sertichi.

a, Ventral view of UA 9972. b, unlabelled, and b′, labelled views of basicranial region indicated by red rectangle in a. Occipital shaded in transparent blue, petrosal in yellow, and squamosal in orange. AS, alisphenoid; BO, basioccipital; BS, basisphenoid; cp, crista parotica; eam, external acoustic meatus; entpt, entopterygoid process; EO, exoccipital; er, epitympanic recess; fi, fossa incudis; fm, foramen magnum; fsh, facet for stylohyal; gf, glenoid fossa; hf, hypoglossal foramina; jf, jugular foramen; lc, fossa for longus capitis; lfl, lateral flange; lt, lateral trough; mrb, median ridge of basioccipital; mt, muscular tubercle; occ, occipital condyle; PE, petrosal; ppr, paroccipital process; ppts, post-promontorial tympanic sinus; pr, promontorium; PT, pterygoid; ptr, pterygopalatine ridge; rcv, fossa for rectus capitis ventralis; sf, stapedius fossa; smn, stylomastoid notch; SQ, squamosal; th, tympanohyal.

Extended Data Figure 5 Composition and features of occipital region of Vintana sertichi.

Posterior view of UA 9972. fm, foramen magnum; FR, frontal; jf, jugal flange; JU, jugal; nc, nuchal crest; OC, occipital; occ, occipital condyle; PA, parietal; PE, petrosal; pgs, postglenoid shelf; PP, postparietal; ppr, paroccipital process; PT, pterygoid; ptf, posttemporal foramen; SQ, squamosal; TA, tabular; zpj, zygomatic process of jugal; zpsq, zygomatic process of squamosal.

Extended Data Figure 6 Dental wear features of Vintana sertichi.

a, Scanning electron micrograph of oblique view of buccal side of occlusal surface of left MF4 cast (see Fig. 2c, d) showing leading (le) and trailing (tr) edges of enamel ridges; white arrow is parallel to wear striae and indicates distobuccal direction of movement of antagonistic lower molariforms. b, Rose diagram of measured wear striation directions on left MF4; black arrow represents mean vector angle of all striations.

Extended Data Figure 7 Relative contributions of the primary muscles of mastication to the total moments about the dentary-squamosal joint axis (DSJ).

Contributions illustrated by vector length during molariform/molar biting at a, b, narrow; and c, d, wide gapes in Vintana sertichi (left) and Myocastor coypus (right). For comparative purposes, the crania are shown at the same length. Only muscles that contributed more than 2% to the total moment about the DSJ axis are illustrated here. This represents 96–98% of the total moment about the axis. adm, anterior deep masseter; iozm, infraorbital portion of zygomaticomandibularis; sm, superficial masseter; t, temporalis; zm, zygomaticomandibularis. All muscles except zm (shown in red) attach to the lateral surface of the cranium and dentary.

Extended Data Figure 8 Sensory anatomy and ecology of Vintana sertichi.

a, Relationship between cranial size and orbital diameter in 352 extant mammalian species (identified according to order; see inset) and V. sertichi (both upper (32 mm) and lower (30 mm) estimates of orbital diameter are depicted). 1, 2, 3, bovids Oreotragus oreotragus, Ourebia ourebi and Raphicerus campestris; 4, 5, 6, felids Lynx rufus, Leptailurus serval and Leopardus pardalis; 7, cervid Mazama gouazoubira. b, Relationship between mean semicircular canal radius of curvature and body mass in 205 extant mammalian species and V. sertichi. The three symbols for Vintana represent its lower, middle and upper body mass estimates. c, Relationship between cochlear canal length and body mass in extinct and extant synapsids, including V. sertichi. The three symbols for Vintana represent its lower, middle and upper body mass estimates. The grey polygon encompasses extant therian mammals. The values for living monotremes do not include the lagenar portion (1, Tachyglossus; 2, Ornithorhynchus). d, Relationship between olfactory bulb volume and body mass in 163 extant and extinct Mammaliaformes, including V. sertichi depicted at lower, average and upper body mass estimates for the reconstructed olfactory bulb volume. See Supplementary Information for more detailed explanations and sources of data.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Text and Data – see contents page for details. (PDF 5365 kb)

Virtual reconstruction of cranium of Vintana sertichi (UA 9972) from μCT dataset, with full rotation (360°) about a dorsoventral axis.

Visualization maps dataset density contrast with false colors resembling those on actual specimen, with the exception of tooth enamel. (MOV 20234 kb)

Virtual reconstruction of cranium of Vintana sertichi (UA 9972) from µCT dataset, with full rotation (360°) about an anteroposterior axis.

Visualization maps dataset density contrast with false colors resembling those on actual specimen, with the exception of tooth enamel. (MOV 21651 kb)

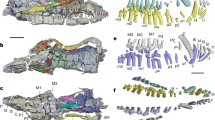

Virtual reconstruction of elements of right side of cranium of Vintana sertichi (UA 9972).

Animation of translation of cranial elements from articulated position to Beauchene-style ("exploded") presentation. Cranial elements presented as polygon surfaces created from segmentation of μCT dataset. (MOV 21674 kb)

Virtual reconstruction of left molariform toothrow (MF2–MF4) of Vintana sertichi (UA 9972) from µCT dataset, with two full rotations (each 360°) about an anteroposterior axis.

First rotation highlights surface morphology. Second rotation highlights internal morphology, with pulp cavities in green and infundibula in blue. (MOV 20924 kb)

Virtual reconstruction of left molariform toothrow (MF2–MF4) of Vintana sertichi (UA 9972) from µCT dataset, with two full rotations (each 360°) about a dorsoventral axis.

First rotation highlights surface morphology. Second rotation highlights internal morphology, with pulp cavities in green and infundibula in blue. (MOV 16652 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krause, D., Hoffmann, S., Wible, J. et al. First cranial remains of a gondwanatherian mammal reveal remarkable mosaicism. Nature 515, 512–517 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13922

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13922

This article is cited by

-

Derived faunivores are the forerunners of major synapsid radiations

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2023)

-

New Skull Material of Taeniolabis taoensis (Multituberculata, Taeniolabididae) from the Early Paleocene (Danian) of the Denver Basin, Colorado

Journal of Mammalian Evolution (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.