Abstract

The response of the terrestrial carbon cycle to climate change is among the largest uncertainties affecting future climate change projections1,2. The feedback between the terrestrial carbon cycle and climate is partly determined by changes in the turnover time of carbon in land ecosystems, which in turn is an ecosystem property that emerges from the interplay between climate, soil and vegetation type3,4,5,6. Here we present a global, spatially explicit and observation-based assessment of whole-ecosystem carbon turnover times that combines new estimates of vegetation and soil organic carbon stocks and fluxes. We find that the overall mean global carbon turnover time is  years (95 per cent confidence interval). On average, carbon resides in the vegetation and soil near the Equator for a shorter time than at latitudes north of 75° north (mean turnover times of 15 and 255 years, respectively). We identify a clear dependence of the turnover time on temperature, as expected from our present understanding of temperature controls on ecosystem dynamics. Surprisingly, our analysis also reveals a similarly strong association between turnover time and precipitation. Moreover, we find that the ecosystem carbon turnover times simulated by state-of-the-art coupled climate/carbon-cycle models vary widely and that numerical simulations, on average, tend to underestimate the global carbon turnover time by 36 per cent. The models show stronger spatial relationships with temperature than do observation-based estimates, but generally do not reproduce the strong relationships with precipitation and predict faster carbon turnover in many semi-arid regions. Our findings suggest that future climate/carbon-cycle feedbacks may depend more strongly on changes in the hydrological cycle than is expected at present and is considered in Earth system models.

years (95 per cent confidence interval). On average, carbon resides in the vegetation and soil near the Equator for a shorter time than at latitudes north of 75° north (mean turnover times of 15 and 255 years, respectively). We identify a clear dependence of the turnover time on temperature, as expected from our present understanding of temperature controls on ecosystem dynamics. Surprisingly, our analysis also reveals a similarly strong association between turnover time and precipitation. Moreover, we find that the ecosystem carbon turnover times simulated by state-of-the-art coupled climate/carbon-cycle models vary widely and that numerical simulations, on average, tend to underestimate the global carbon turnover time by 36 per cent. The models show stronger spatial relationships with temperature than do observation-based estimates, but generally do not reproduce the strong relationships with precipitation and predict faster carbon turnover in many semi-arid regions. Our findings suggest that future climate/carbon-cycle feedbacks may depend more strongly on changes in the hydrological cycle than is expected at present and is considered in Earth system models.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Climate-carbon cycle feedback analysis: results from the (CMIP)-M-4 model intercomparison. J. Clim. 19, 3337–3353 (2006)

Ciais, P. et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) 465–570 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013)

King, A. W., Post, W. M. & Wullschleger, S. D. The potential response of terrestrial carbon storage to changes in climate and atmospheric CO2 . Clim. Change 35, 199–227 (1997)

Sitch, S. et al. Evaluation of ecosystem dynamics, plant geography and terrestrial carbon cycling in the LPJ dynamic global vegetation model. Glob. Change Biol. 9, 161–185 (2003)

Trumbore, S. Age of soil organic matter and soil respiration: radiocarbon constraints on belowground C dynamics. Ecol. Appl. 10, 399–411 (2000)

Friend, A. D. et al. Carbon residence time dominates uncertainty in terrestrial vegetation responses to future climate and atmospheric CO2 . Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 111, 3280–3285 (2014)

Denman, K. L. et al. in Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis (eds Solomon, S. et al.) 499–587 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2007)

Heimann, M. & Reichstein, M. Terrestrial ecosystem carbon dynamics and climate feedbacks. Nature 451, 289–292 (2008)

Anav, A. et al. Evaluating the land and ocean components of the global carbon cycle in the CMIP5 earth system models. J. Clim. 26, 6801–6843 (2013)

Rodhe, H. in Global Biogeochemical Cycles (eds Charlson, R. J., Butcher, S. S., Orians, G. H. & Wolfe, G. V. ) Ch. 4 (Academic, 1992)

Malhi, Y., Saatchi, S., Girardin, C. & Aragão, L. E. O. C. in Amazonia and Global Change (eds Keller, M., Bustamante, M., Gash, J. & Silva Dias, P. ) 355–372 (American Geophysical Union, 2009)

Trumbore, S. Carbon respired by terrestrial ecosystems — recent progress and challenges. Glob. Change Biol. 12, 141–153 (2006)

Sundquist, E. T. in The Carbon Cycle and Atmospheric CO: Natural Variations, Archean to Present (eds Sundquist, E. T. & Broecker, W. S. ) 5–59 (American Geophysical Union, 1985)

Kätterer, T., Reichstein, M., Andren, O. & Lomander, A. Temperature dependence of organic matter decomposition: a critical review using literature data analyzed with different models. Biol. Fertil. Soils 27, 258–262 (1998)

Davidson, E. A. & Janssens, I. A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 440, 165–173 (2006)

Bond-Lamberty, B. & Thomson, A. Temperature-associated increases in the global soil respiration record. Nature 464, 579–582 (2010)

Cleveland, C. C. & Townsend, A. R. Nutrient additions to a tropical rain forest drive substantial soil carbon dioxide losses to the atmosphere. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 10316–10321 (2006)

Houghton, R. A. Revised estimates of the annual net flux of carbon to the atmosphere from changes in land use and land management 1850–2000. Tellus B 55, 378–390 (2003)

Nepstad, D. C. et al. Large-scale impoverishment of Amazonian forests by logging and fire. Nature 398, 505–508 (1999)

Thonicke, K., Venevsky, S., Sitch, S. & Cramer, W. The role of fire disturbance for global vegetation dynamics: coupling fire into a dynamic global vegetation model. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 10, 661–677 (2001)

Krawchuk, M. A. & Moritz, M. A. Constraints on global fire activity vary across a resource gradient. Ecology 92, 121–132 (2011)

Vetaas, O. R. Micro-site effects of trees and shrubs in dry savannas. J. Veg. Sci. 3, 337–344 (1992)

Joffre, R. & Rambal, S. How tree cover influences the water-balance of Mediterranean rangelands. Ecology 74, 570–582 (1993)

Belsky, A. J. Influences of trees on savanna productivity — tests of shade, nutrients, and tree-grass competition. Ecology 75, 922–932 (1994)

Fahey, T. J. et al. The biogeochemistry of carbon at Hubbard Brook. Biogeochemistry 75, 109–176 (2005)

Bondeau, A. et al. Modelling the role of agriculture for the 20th century global terrestrial carbon balance. Glob. Change Biol. 13, 679–706 (2007)

Todd-Brown, K. E. O. et al. Causes of variation in soil carbon simulations from CMIP5 Earth system models and comparison with observations. Biogeosciences 10, 1717–1736 (2013)

Vonk, J. E. & Gustafsson, O. Permafrost-carbon complexities. Nature Geosci. 6, 675–676 (2013)

Koven, C. et al. On the formation of high-latitude soil carbon stocks: Effects of cryoturbation and insulation by organic matter in a land surface model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L21501 (2009)

Janssens, I. A. et al. Reduction of forest soil respiration in response to nitrogen deposition. Nature Geosci. 3, 315–322 (2010)

Xia, J. Y., Luo, Y. Q., Wang, Y. P. & Hararuk, O. Traceable components of terrestrial carbon storage capacity in biogeochemical models. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 2104–2116 (2013)

Wieder, W. R., Bonan, G. B. & Allison, S. D. Global soil carbon projections are improved by modelling microbial processes. Nature Clim. Change 3, 909–912 (2013)

FAO/IIASA/ISRIC/ISSCAS/JRC. Harmonized World Soil Database v 1. 2http://webarchive.iiasa.ac.at/Research/LUC/External-World-soil-database/HTML/ (2012)

Jobbágy, E. G. & Jackson, R. B. The vertical distribution of soil organic carbon and its relation to climate and vegetation. Ecol. Appl. 10, 423–436 (2000)

Schrumpf, M., Schulze, E. D., Kaiser, K. & Schumacher, J. How accurately can soil organic carbon stocks and stock changes be quantified by soil inventories? Biogeosciences 8, 1193–1212 (2011)

Webb, R. W., Rosenzweig, C. E. & Levine, E. R. Global Soil Texture and Derived Water-Holding Capacities (Webb et al.) http://daac.ornl.gov/cgi-bin/dsviewer.pl?ds_id=548 (Oak Ridge National Laboratory Distributed Active Archive Center, 2000)

Zobler, L. A World Soil File for Global Climate Modelling. Report No. 87802 (NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, 1986)

Hugelius, G. et al. The Northern Circumpolar Soil Carbon Database: spatially distributed datasets of soil coverage and soil carbon storage in the northern permafrost regions. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 5, 3–13 (2013)

Tarnocai, C. et al. Soil organic carbon pools in the northern circumpolar permafrost region. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 23, GB2023 (2009)

Saatchi, S. S. et al. Benchmark map of forest carbon stocks in tropical regions across three continents. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 9899–9904 (2011)

Thurner, M. et al. Carbon stock and density of northern boreal and temperate forests. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 23, 297–310 (2014)

Santoro, M. et al. in Proc. ESA Living Planet Symp. SP-722 (CD-ROM, ESA Communication Office, 2013)

Amthor, J. S. The McCree-de Wit-Penning de Vries-Thornley respiration paradigms: 30 years later. Ann. Bot. (Lond.) 86, 1–20 (2000)

Jung, M. et al. Global patterns of land-atmosphere fluxes of carbon dioxide, latent heat, and sensible heat derived from eddy covariance, satellite, and meteorological observations. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 116, G00J07 (2011)

Jung, M., Henkel, K., Herold, M. & Churkina, G. Exploiting synergies of global land cover products for carbon cycle modeling. Remote Sens. Environ. 101, 534–553 (2006)

Kauppi, P. E. New, low estimate for carbon stock in global forest vegetation based on inventory data. Silva Fenn. 37, 451–457 (2003)

Rodhe, H. in Global Biogeochemical Cycles (eds Butcher, S. S., Charlson, R. J., Orians, G. H. & Wolfe, G. V. ) 55–72 (Academic, 1992)

Jenkinson, D. S. in Russell’s Soil Conditions and Plant Growth (ed. Wild, A. ) 564–607 (Longman Scientific and Technical, 1988)

Schlesinger, W. H. in Soils and Global Change Vol. 25 (eds Lal, R., Kimble, J., Levine, E. & Stewart, B. A. ) 9–25 (CRC/Lewis Publishers, 1995)

Oades, J. M. The retention of organic-matter in soils. Biogeochemistry 5, 35–70 (1988)

Bird, M. I., Chivas, A. R. & Head, J. A latitudinal gradient in carbon turnover times in forest soils. Nature 381, 143–146 (1996)

Ito, A. A historical meta-analysis of global terrestrial net primary productivity: are estimates converging? Glob. Change Biol. 17, 3161–3175 (2011)

Zaks, D. P. M., Ramankutty, N., Barford, C. C. & Foley, J. A. From Miami to Madison: investigating the relationship between climate and terrestrial net primary production. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 21, GB3004 (2007)

Del Grosso, S. et al. Global potential net primary production predicted from vegetation class, precipitation, and temperature. Ecology 89, 2117–2126 (2008)

Lieth, H. in Primary Productivity of the Biosphere (eds Lieth, H. & Whittaker, R. H. ) 237–263 (Springer, 1975)

Lieth, H. & Box, E. in Publications in Climatology (ed. Thornthwaite, W. ) 37–46 (C.W. Thornthwaite Associates, 1972)

Schuur, E. A. G. Productivity and global climate revisited: the sensitivity of tropical forest growth to precipitation. Ecology 84, 1165–1170 (2003)

Dee, D. P. et al. The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 137, 553–597 (2011)

Beer, C. et al. Harmonized European long-term climate data for assessing the effect of changing temporal variability on land-atmosphere CO2 fluxes. J. Clim. 27, 4815–4834 (2014)

Weedon, G. P. et al. Creation of the WATCH forcing data and its use to assess global and regional reference crop evaporation over land during the twentieth century. J. Hydrometeorol. 12, 823–848 (2011)

Piani, C. et al. Statistical bias correction of global simulated daily precipitation and temperature for the application of hydrological models. J. Hydrol. (Amst.) 395, 199–215 (2010)

Lindeman, R. H., Merenda, P. F. & Gold, R. Z. Introduction to Bivariate and Multivariate Analysis (1980)

Grömping, U. Relative importance for linear regression in R: the package relaimpo. J. Stat. Softw. 17, 1–27 (2006)

Zhang, K., Peters, J., Janzing, D. & Schölkopf, B. Kernel-based conditional independence test and application in causal discovery. Computing Res. Repos. (arXiv, 2012)

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J. & Meehl, G. A. An Overview of Cmip5 and the Experiment Design. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 485–498 (2012)

Prentice, I. C. et al. in Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis (eds Houghton, J. T. et al.) 183–237 (Cambridge Univ Press, 2001)

Beer, C. et al. Terrestrial gross carbon dioxide uptake: global distribution and covariation with climate. Science 329, 834–838 (2010)

Kottek, M., Grieser, J., Beck, C., Rudolf, B. & Rubel, F. World map of the Koppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. (Berl.) 15, 259–263 (2006)

Turetsky, M. R. et al. The resilience and functional role of moss in boreal and arctic ecosystems. New Phytol. 196, 49–67 (2012)

Page, S. E., Rieley, J. O. & Banks, C. J. Global and regional importance of the tropical peatland carbon pool. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 798–818 (2011)

DiMiceli, C. M. et al. Annual Global Automated MODIS Vegetation Continuous Fields (MOD44B) at 250 m Spatial Resolution for Data Years Beginning Day 65, 2000 - 2010, Collection 5 Percent Tree Coverhttp://glcf.umd.edu/data/vcf/ (University of Maryland, 2011)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank C. Jones for comments that improved the manuscript. We are grateful to A. Ito, D. Zaks and S. Del Grosso for sharing their NPP data sets with us. We thank S. Schott for figure editing. We acknowledge support by the European Union (FP7) through the projects GEOCARBON (283080), CARBONES (242316) and EMBRACE (283201) and an ERC starting grant QUASOM (ERC-2007-StG-208516).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.C. and M.R. designed the study and are responsible for the integrity of the work as a whole. N.C., M.F. and M. Migliavacca performed analysis and calculations. N.C. and M.R. mainly wrote the manuscript. M.K. and J.B. contributed to interpreting and processing the soil databases. M.T., M.S. and S.S. contributed to the vegetation carbon stocks datasets and interpretation. M.J. contributed to the GPP datasets and interpretation. C.B., M. Mu, M.T. and U.W. contributed to data provision, analysis or data processing. A.C., B.A., M.F., M.J. and J.T.R. contributed to analysis design and interpretation. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Figure 1 Relative uncertainties in total ecosystem carbon.

Relative uncertainties in total ecosystem carbon stemming from the different data sources considered, reported as the ratio between the interquartile range (difference between the 75th and 25th percentiles) of the different estimates and the mean. The colour scale is binned to the 98th percentile of the spatial distribution of uncertainty (140%). A significant spatial variability was observed in the total ecosystem carbon uncertainties. The highest uncertainties locally and regarding total stocks per biome were observed in tundra (∼38%), followed by tropical savannahs and grasslands (∼30%). Deserts and croplands also showed significant relative uncertainties (both 27%). Overall, we observe a global relative uncertainty of 21%. We note unknown sources of uncertainties related to total carbon stocks, which relate mostly the representativeness of mosses in northern latitudes69 and tropical peatlands in Southeast Asia, although we find a total soil stock of  PgC (95% CI) in this region (−11.5° < latitude < 10° and 90° < longitude < 155°), which borders the upper envelope of the estimates in ref. 70.

PgC (95% CI) in this region (−11.5° < latitude < 10° and 90° < longitude < 155°), which borders the upper envelope of the estimates in ref. 70.

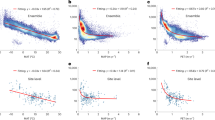

Extended Data Figure 2 Local spatial correlations between turnover times of carbon in terrestrial ecosystems and temperature, and precipitation.

Local spatial correlations between τ and temperature (tas; a, c, e), and τ and precipitation (pr; b, d, f) using the 5.5°-by-5.5° moving-window approach. We use two alternative approaches to the Pearson correlation (a, b): the Spearman rank correlation (rsp.), a non-parametric measure of association that does not rely on the assumption of normal distribution of residuals (c, d); and the partial correlation (rp, e, f), measuring the degree of association between τ and temperature or precipitation, setting precipitation or, respectively, temperature as controlling variables (e, f). On local scales, using partial correlations may result in lost correlation owing to a strong local covariation of temperature and precipitation. Although we see this loss, the associative patterns between τ and both climate variables are generally maintained across the approaches used to calculate the correlations.

Extended Data Figure 3 Strength of association between turnover times of carbon in terrestrial ecosystems and temperature, and precipitation, using different methods.

Strength of association between τ and temperature (tas) and precipitation (pr) for Pearson correlations (a), Spearman correlations (b) and partial correlations (c). Each of these maps (a–c) shows regions where the association of τ is stronger with precipitation (blue) or temperature (red). The fraction of land grid cells with stronger significant correlations to temperature and precipitation are indicated above (for tas) and below (for pr) the colour bar. The colour gradients reflect the respective absolute correlation values. Despite stronger correlations with either temperature or precipitation, these cannot be said to be completely independent from the variable with lower correlation strength. d, Results of a conditional independence test on rejecting the null hypothesis that τ is independent from pr or tas given tas or, respectively, pr (ref. 64), showing that in 53% of the land grid cells, the dependence of τ on temperature or precipitation is not lost when controlling for precipitation or, respectively, temperature.

Extended Data Figure 4 Maximum relative importance of temperature and precipitation in the explained variance of turnover times of carbon.

a, Maximum relative importance of temperature (tas) or precipitation (pr) in the explained variance of τ using the LMG method. b, Relative importance of temperature (tas) or precipitation (pr) in improving the residual sum of squares of local bivariate regressions of τ against tas and pr. c, Normalized slopes of the bivariate regression between τ and precipitation and temperature, using a stepwise regression approach. Also, here the slopes correlate significantly with the strength of the association between the two variables. The fraction of land grid cells with stronger significant correlations to temperature and precipitation are indicated above (for tas) and below (for pr) the colour bar.

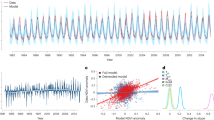

Extended Data Figure 5 Moving-window correlation between turnover times of carbon in terrestrial ecosystems and vegetation, and soil carbon stocks.

Moving-window correlation between τ and vegetation stocks (a); and between τ and carbon in soils (b). In general, τ correlates negatively with vegetation (a), indicating shorter turnover times with a higher proportion of carbon in the vegetation. The majority of the patterns are consistent with the overall reduction of residence times in ecosystem carbon given allocation to vegetation pools (shorter lived by comparison with soil carbon pools). Conversely, the significance of soil carbon stocks in explaining the spatial variability of τ is pervasive (b). These results translate the trends in increasing τ with allocation of assimilated carbon to more persistent carbon pools.

Extended Data Figure 6 Pearson correlations between turnover times of carbon in terrestrial ecosystems and tree cover, also controlled for the variability in precipitation.

a, Pearson correlations between τ and tree cover. The prevalence of strong negative correlations suggests that the association could be mediated by precipitation variability. b, Controlling for precipitation still showed many of those negative correlation regions. These negative correlations are most clear in regions where tree cover is not so high or where spatial variability seems higher. c, Map of tree cover percentage from MODIS71.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Text and Data 1-6, Supplementary References, Supplementary Tables 1-7 and Supplementary Figures 1-13. Please note that you can download the Supplementary Data, relating to this paper, at the following link: http://www.bgc-jena.mpg.de/geodb/BGI/tau.php (PDF 7449 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carvalhais, N., Forkel, M., Khomik, M. et al. Global covariation of carbon turnover times with climate in terrestrial ecosystems. Nature 514, 213–217 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13731

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13731

This article is cited by

-

Towards an increasingly biased view on Arctic change

Nature Climate Change (2024)

-

Soil organic carbon losses exacerbated by climate extremes

Nature Climate Change (2024)

-

Carbon sink response of terrestrial vegetation ecosystems in the Yangtze River Delta and its driving mechanism

Journal of Geographical Sciences (2024)

-

Disentangling the effects of temperature and reactive minerals on soil carbon stocks across a thermal gradient in a temperate native forest ecosystem

Biogeochemistry (2024)

-

Temperature effect on erosion-induced disturbances to soil organic carbon cycling

Nature Climate Change (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.