Abstract

It has been suggested that the superiority of antidepressants over placebo in controlled trials is merely a consequence of side effects enhancing the expectation of improvement by making the patient realize that he/she is not on placebo. We explored this hypothesis in a patient-level post hoc-analysis including all industry-sponsored, Food and Drug Administration-registered placebo-controlled trials of citalopram or paroxetine in adult major depression that used the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) and included a week 6 symptom assessment (n=15). The primary analyses, which compared completers on active treatment without early adverse events to completers on placebo (with or without adverse events) with respect to reduction in the HDRS depressed mood item showed larger symptom reduction in patients given active treatment, the effect sizes being 0.48 for citalopram and 0.33 for paroxetine. In actively treated subjects reporting early adverse events, who also outperformed those given placebo, the severity of the adverse events did not predict response. Several sensitivity analyses, for example, including (i) those using change of the sum of all HDRS-17 items as effect parameter, (ii) those excluding all subjects with adverse events (that is, also those on placebo) and (iii) those based on the intention-to-treat population, were all in line with the primary analyses. The finding that both paroxetine and citalopram are clearly superior to placebo also when not producing adverse events, as well as the lack of association between adverse event severity and response, argue against the theory that antidepressants outperform placebo solely or largely because of their side effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The possible existence of a specific pharmacological antidepressant effect has become one of the major controversies in current medicine. Questioning the traditional view that drugs named antidepressants act by influencing certain brain neurotransmitters, it has hence been suggested that their superiority over placebo in controlled trials is merely a psychological consequence of the side effects of the drugs enhancing the expectation of improvement by making the patient realize that he/she is not on placebo.1,2,3,4 If this hypothesis, which has gained widespread attention in lay media,5,6,7,8 is correct, the extensive use of these drugs must be reconsidered. But should it be false, it is important to have this clarified, so that doctors are not groundlessly discouraged from prescribing effective medication.

There have been previous attempts to shed light on the possible association between the presence of antidepressant-induced side effects and response by means of trial-level meta-analyses but with discordant and inconclusive results.9,10 However, whereas these studies have been based on the assumption that there may be marked inter-trial differences with respect to the propensity of the participants to experience selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)-induced side effects that translate into corresponding differences in response rate, it may be argued that the difference in propensity to side effects of possible relevance in this context should reside between individuals rather than between trial populations. For this reason, and considering that patient-level mega-analyses and meta-analyses of trial-level data may differ significantly in outcome,11 a more informative approach to address this problem may be to compare the response in patients reporting and not reporting adverse events, respectively. To this end, we have conducted what we believe are the first patient-level mega-analyses investigating (i) whether the presence of adverse events is necessary for SSRIs to outperform placebo and (ii) whether the presence of adverse events, or adverse event severity, is associated with response in patients treated with SSRIs

Materials and methods

Data acquisition and verification

We requested patient-level data regarding item-wise symptom ratings and timing of adverse events for all industry-sponsored, Food and Drug Administration-registered, placebo-controlled trials regarding adult major depression that have been conducted for fluoxetine (Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA), sertraline (Pfizer, New York, NY, USA), paroxetine (GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Brentford, UK) and citalopram (Lundbeck, Valby, Denmark). Lilly could not provide us with the requested information regarding fluoxetine, as these data are not available in electronic format, and Pfizer could not provide us with data regarding the timing of adverse events for the sertraline trials. GSK and Lundbeck could however provide us with the requested information regarding paroxetine and citalopram, respectively. To be eligible for inclusion, the trial should have used the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) for symptom rating and include an assessment at week 6. Examination of the Food and Drug Administration Approval Packages for the two drugs12,13,14 confirmed that we had access to all pertinent studies regarding these two drugs with the exception of two small trials, which, according to the Food and Drug Administration approval packages, were prematurely terminated: GSK/07,12 which randomized 13 patients on paroxetine (8 completers) and 12 patients on placebo (7 completers), and LB/87A,13 which randomized 17 patients on citalopram (5 completers) and 17 patients on placebo (4 completers). In addition to the Food and Drug Administration-registered trials, GSK also provided data from four post-registration trials regarding paroxetine.

Aims

The aims of this study were threefold. One was to assess to what extent presence of adverse events constitutes an indispensable prerequisite for antidepressants to outperform placebo, a second to assess whether the presence of adverse events (yes/no) is associated with response in SSRI-treated subjects and a third to assess whether severity of adverse events is associated with response in SSRI-treated subjects.

Comparisons

The decision on which analyses should be regarded as primary when assessing the difference between active drug and placebo in subjects with or without adverse events was based on a number of methodological considerations. First, adverse events may prompt some patients to discontinue treatment before having had a chance to improve; including dropouts in the analysis might hence mask a possible positive association between side effects and response. To avoid this potential source of bias, which might lead to an erroneous falsification of the placebo-breaking-the-blind hypothesis, only patients completing the trial were included in the primary analyses. Second, as a number of potential side effects of SSRIs (for example, weight change, insomnia, gastrointestinal symptoms and sexual dysfunction) are listed as possible symptoms of depression in the HDRS-17,15 using the total sum of the ratings of the different items in this scale (HDRS-17-sum) as effect parameter, which has been the conventional way of establishing efficacy in antidepressant trials,16 might also mask a possible association between adverse events and response. For this reason, only one item from the HDRS-17, depressed mood, which was recently shown to be a more sensitive measure for detecting differences between active drug and placebo,17,18 was used as primary measure of efficacy. Third, in clinical trials one usually records any novel complaint appearing during treatment as an adverse event regardless of whether it is likely to be a side effect of the given treatment or not.19 As most side effects of SSRIs appear shortly after the initiation of treatment, and as the side-effect-breaking-the-blind hypothesis implies that side effects should precede or appear simultaneously as the symptom reduction, we reasoned that restricting the primary analyses to adverse events appearing during the first 2 weeks of treatment would optimize the likelihood of establishing an association between side effects and response. Fourth, as it could be argued that the presence of one mild side effect would be sufficient to make the patient realize that he/she has not been given placebo, in the primary analyses adverse events were handled as a dichotomous yes/no variable rather than rated with respect to severity.

Although the primary analyses hence were based on the completer population, used the single item depressed mood (rated 0–4) from the HDRS-17 as outcome parameter and only considered the presence of adverse events (yes/no) during the first 2 weeks of double-blind treatment, a number of sensitivity analyses were undertaken to assess the results of alternative approaches. When splitting the active treatment groups, we thus (i) considered not only adverse events during week 1–2 but also those reported during the run-in period, where all subjects received placebo single-blindly; (ii) considered only adverse events during week 1 (rather than during weeks 1–2); (iii) considered all adverse events reported at any time during weeks 1–6; and (iv) considered only those adverse events during weeks 1–2 that were not present also before randomization. For the paroxetine trials, the effect of taking only those adverse events that the investigator regarded as possibly and/or probably related to treatment into account when splitting the active treatment groups was also assessed; for the citalopram trials, the corresponding analyses could not be undertaken, as this information was not available. The primary analyses were also repeated using HDRS-17-sum rather than depressed mood as effect parameter and analyzing the intention-to-treat rather than the completer population, respectively. Finally, although we judge the comparison of SSRI-treated patients not reporting adverse events with all placebo-treated patients to be the most relevant one, we also compared SSRI-treated subjects reporting no early adverse event with placebo-treated patients also reporting no early adverse event and SSRI-treated subjects reporting at least one early adverse event with placebo-treated patients also reporting at least one early adverse event.

Statistics

Citalopram and paroxetine trials were analyzed separately. Analysis of covariance with baseline values on the outcome measure included as a covariate and trial as a fixed factor was used in all models. When investigating whether presence of adverse events is necessary for active drug to outperform placebo, a three category variable classifying patients as either placebo-treated, SSRI-treated without early (weeks 1–2) adverse events, or SSRI-treated with early adverse events was included as a fixed factor. Effect sizes (ESs) were calculated by dividing the least squares mean differences between groups by the root mean squared error of the model.

The various sensitivity analyses based on alternate outcome measures and adverse event timings (see above) all used the same model specification as the primary analyses. In the intention-to-treat analyses, the last observation carried forward procedure was used to obtain ratings for all patients with at least one post-baseline visit. When assessing the impact of investigator-judged relatedness of adverse events to treatment, the group of paroxetine-treated patients was divided based on whether or not the patients experienced (i) at least one early adverse event deemed as probably treatment-related or (ii) at least one early adverse event deemed as probably or possibly treatment-related. For the comparison of SSRI- and placebo-treated patients with early adverse events, and of SSRI- and placebo-treated patients without early adverse events, respectively, the populations were stratified according to whether or not they had reported at least one adverse event during weeks 1–2. For this analysis, the three-category variable was substituted with a binary treatment factor (SSRI or placebo); otherwise the model was identical.

For the assessment of the possible association between adverse event severity and reduction in depressed mood, SSRI-treated subjects reporting adverse events during weeks 1–2 were divided into three groups: those for which the most severe adverse event was rated as mild, moderate and severe, respectively. This was coded into a variable with three categories and included as a fixed factor. Placebo-treated patients as well as SSRI-treated patients reporting no early adverse events were excluded from this analysis.

All analyses of citalopram data were carried out locally using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). For the paroxetine trials, remote desktop access to the Clinical Trial Data Transparency environment was provided by the Clinical Study Data Request website through SAS Solutions OnDemand, again using SAS version 9.4.

Ethics

The Regional Ethical Review Board reviewed the study protocol and issued an advisory opinion stating no objection.

Results

Trials and patients

Baseline characteristics of the included trials are summarized in Table 1. An endpoint observation was available for 2759 patients (939 on placebo) from the paroxetine trials and for 585 patients (132 on placebo) from the citalopram trials.

Comparisons of active drug and placebo in patients with or without adverse events

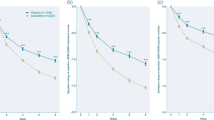

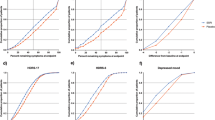

Paroxetine-treated patients both with and without early adverse events outperformed those given placebo with respect to reduction in depressed mood (Figure 1). Similarly, for citalopram-treated patients both those reporting and those not reporting early adverse events fared better than the placebo group with regard to depressed mood (Figure 2). A number of sensitivity analyses exploring alternative strategies for defining presence of adverse events, that is, (i) considering also adverse events during the placebo run-in phase, (ii) only considering adverse events appearing during week 1, (iii) considering all adverse events reported during week 1–6, (iv) only considering those adverse events that were not present prior to study start, or (v) only considering adverse events that were regarded as possibly or probably related to treatment by the investigator, all corroborated the results of the primary analyses (Supplementary Figures 1–10). Likewise, sensitivity analyses using the HDRS-17-sum as outcome parameter were in line with those of the primary analyses (Supplementary Figures 11 and 12), one notable exception being that citalopram-treated patients with adverse events did not significantly outperform the placebo group with respect to HDRS-17-sum reduction; in contrast, citalopram-treated patients without adverse events did (Supplementary Figure 12). Analyses based on the intention-to-treat population were in line with those of the primary analyses (Supplementary Figures 13 and 14). Similarly, analyses stratifying not only the SSRI group but also the placebo group according to the presence of early adverse events revealed significant superiority of active treatment both for patients with early adverse events (citalopram ES 0.28, 0.05–0.51, P=0.02; paroxetine ES 0.47, 0.37–0.57, P<0.001) and for patients without early adverse events (citalopram ES 0.52, 0.14–0.90; P=0.008; paroxetine ES 0.33, 0.19–0.48; P<.001).

Rating of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) depressed mood item (0–4) after 6 weeks of treatment in patients treated with placebo and patients treated with paroxetine stratified by presence of adverse events during weeks 1–2. Adjusted means and standard errors from the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model.

Rating of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) depressed mood item (0–4) after 6 weeks of treatment in patients treated with placebo and patients treated with citalopram stratified by presence of adverse events during weeks 1–2. Adjusted means and s.e. from the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model.

Assessment of the influence of adverse events on the effect of active drug

According to the primary analysis as well as various sensitivity analyses, paroxetine-treated subjects reporting early adverse events displayed a small but significant superiority with respect to reduction in depressed mood as compared with those not reporting early adverse events; no corresponding association between adverse events and response was observed in the citalopram trials (Figures 1 and 2, and Supplementary Figures 1–10 and 13 and 14). For neither the paroxetine nor the citalopram trials were there any significant differences between patients reporting or not reporting early adverse events with respect to reduction in HDRS-17-sum (Supplementary Figures 11 and 12).

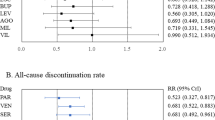

Influence of adverse event severity on response in patients on active treatment

Neither for patients treated with paroxetine (Figure 3) nor for those treated with citalopram (Figure 4) was the degree of severity of the most severe adverse event associated with reduction in depressed mood.

Discussion

The major finding of this study is that patients treated with either paroxetine or citalopram report a larger reduction in depressed mood than those given placebo regardless of if they report adverse events or not. As such an outcome is not compatible with the theory that the beneficial effect of antidepressants is largely or solely the result of these drugs enhancing the expectation of improvement by causing side effects,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 our results indirectly support the notion that the two drugs under study do display genuine antidepressant effects caused by their pharmacodynamic properties.

Whereas the primary analyses addressed the possible influence of adverse events occurring during weeks 1–2 on the reduction in depressed mood in the observed cases population, a number of sensitivity analyses using alternative strategies for addressing the issue at stake were also undertaken. For example, as it may be argued that only adverse events that are likely to be the result of SSRI administration should lead to unblinding, two of these analyses addressed the effect of only considering those adverse events which were judged as possibly and/or probably related to paroxetine treatment by the investigator; the outcome of these were however entirely in line with those of the primary analyses. Likewise, sensitivity analyses (i) assessing the possible effect of replacing depressed mood with HDRS-17-sum as primary effect parameter (ii) including all subjects with at least one post-baseline visit using the last-observation-carried forward principle (the intention-to-treat population) rather than just completers, or (iii) modifying the criteria for when the adverse events should occur to be considered, also provided no reason to revise the conclusion based on the primary analyses. Moreover, the outcome of comparisons of SSRI-treated subjects without early adverse events with placebo-treated subjects also without early adverse events and of SSRI-treated subjects with early adverse events with placebo-treated subjects also reporting early adverse events, were in line with those of the primary analyses. Finally, sensitivity analyses using the full HDRS-17-sum as outcome parameter showed similar results as those regarding depressed mood, a notable exception being that citalopram-treated patients with adverse events did not significantly outperform placebo-treated patients (while citalopram-treated patients without adverse events did) (Supplementary Figures 11 and 12).

Paroxetine-treated patients consistently displayed a small but significant positive association between early adverse events and reduction in depressed mood (but not HDRS-17-sum). Whereas this observation could be interpreted as support for side effects exerting some impact on the response to the drug through unblinding, side effects and response might obviously correlate, without being causally related, due to inter-individual differences in factors such as dose, compliance, drug metabolism and responsiveness to the pharmacodynamic effects of the drug. Notably, we however observed no corresponding association in citalopram-treated subjects. Although there is no obvious explanation as to why the data regarding the two drugs differ in this regard, this may tentatively be related to differences with respect to how the two companies designed their trials with respect to dose levels, dosing regime (that is, fixed doses versus flexible dosing) and how adverse event information was obtained, but possibly also to drug-related differences in adverse event acceptability at the elected dose levels. Of note is that there were no significant associations between early adverse events and response in placebo-treated patients in either the citalopram or the paroxetine trials (data not shown).

Whereas the presence of side effects was hence not a strong predictor for response in SSRI-treated subjects, it should be noted that all studies utilized a single-blind placebo lead-in period that might eliminate patients most inclined to experience an expectation-induced symptom relief. This possibility, however, has no bearing on the issue addressed in this study, that is, whether the difference between active drug and placebo observed in many controlled trials may be attributed to side effects breaking the blind in patients given active medication.

The primary analyses as well as most of the sensitivity analyses suggest the ESs for the reduction in depressed mood in patients not reporting adverse events to be between 0.3 and 0.5, that is, small to moderate. When interpreting these results in terms of clinical significance, one should consider the fact that many of the included trials comprised treatment arms with suboptimal dosage; the presented ESs, similar to those obtained in most meta-analyses regarding antidepressants, are hence lower than one may expect when using adequate doses.18

The fact that the presence of side effects might compromise the integrity of the double-blind procedure in both raters20,21,22,23 and patients,3,24,25,26 and that the resulting unblinding may introduce a bias favoring the active drug, has been discussed since long. During the '60s and '70s, when most antidepressants displayed easily recognizable anticholinergic side effects, attempts were made to explore this possibility by comparing antidepressants with so-called active placebos, that is, drugs exerting no antidepressant effect but being anticholinergic. Finding the ES for the difference between tricyclic antidepressants and such active placebos to be small (0.17), the authors of a Cochrane report27 suggested the specific effects of antidepressants to be overestimated. Several of the nine studies analyzed, six of which were conducted in the '60s, were however small and/or marred by methodological shortcomings including short duration and possible underdosing. Moreover, the modest ES of 0.17 was obtained after a post hoc exclusion of a trial regarded as an outlier. Including this trial yielded a highly significant difference between antidepressants and active placebo with an ES of 0.39, which is well in line with studies comparing antidepressants with inert placebos. Of note is also that other authors analyzing this literature have concluded that the outcome of trials using active placebo do not support the suggestion that the studied drugs lack specific antidepressant properties.28,29

Another argument that has been put forward, for example by Kirsch,6 as support for the placebo-breaking-the-blind hypothesis is that an analysis based on six trials comparing the SSRI fluoxetine with placebo showed side effects to correlate significantly with efficacy.9 However, this study did not analyze the association between side effects and response in individual patients but used trial level meta-analysis. Of note is also that a more recent trial-based meta-analysis, including a much larger set of studies (n=68), failed to replicate the correlation.10

Supporting the assumption that antidepressants do not act merely by means of a placebo effect, depressed patients were treated with drugs, including central stimulants, barbiturates, opiates and antipsychotics, but without satisfactory effect,30 even before the serendipitous discovery of the first antidepressants, imipramine and iproniazide;31 had drug treatment of depression been merely a matter of a psychological placebo response, these compounds should have appeared just as effective as imipramine or iproniazide. Moreover, a large number of trials have revealed significant differences between two antidepressants (or putative antidepressants) in trials including no placebo arm;32,33,34,35,36 had the superiority of antidepressants over placebo in controlled trials been merely the result of the patient realizing that he/she has not been given active treatment, such an outcome would be difficult to explain given that the participants in these trials knew that they were not at risk of receiving placebo. The present data, suggesting that antidepressants do not act merely by means of a placebo effect, are well in line with these observations.

Two limitations of this study should be addressed. First, as it only includes data from studies regarding paroxetine or citalopram, it does not allow any conclusions regarding the possible influence of side effects on the response to other antidepressants. The observation that, for these two drugs, a clear-cut difference between groups was observed also in patients not reporting adverse events should however be sufficient to falsify the theory that all drugs regarded as antidepressants exert their action merely by means of their side effects. Second, the possibility that subtle adverse events that are recognized by the patient, but not of sufficient severity to be recorded, could influence the expectation of improvement, should not be excluded. However, the relatively low percentage of patients not reporting any early adverse events in most trials argues against side effects being under-reported. Of note in this context is that the suggestion by Kirsch of an association between side effect severity and response6 gained no support from the analyses assessing this possibility (Figures 3 and 4).

In summary, although this study does not allow any firm conclusions with respect to the possible existence of a modest association between early side effects and antidepressant response for SSRIs, the results for paroxetine and citalopram being divergent in this regard, it casts serious doubt on the assumption that the superiority of antidepressants over placebo is entirely or largely due to side effects enhancing the placebo effect of the active compound by breaking the blind. We conclude that that the placebo-breaking-the-blind theory has come to influence the current view on the efficacy of antidepressants to a greater extent than can be justified by available data.

References

Kirsch I, Sapirstein G. Listening to Prozac but hearing placebo: a meta-analysis of antidepressant medication. Prevent Treat 1998; 1, Article 2a.

Moncrieff J. Are antidepressants as effective as claimed? No, they are not effective at all. Can J Psychiatry 2007; 52: 96–97.

Kirsch I. The emperor's new drugs: medication and placebo in the treatment of depression. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2014; 225: 291–303.

Moncrieff J. Antidepressants: misnamed and misrepresented. World Psychiatry 2015; 14: 302–303.

Begley S. Why Antidepressants Are No Better Than Placebos. Newsweek. 29 January 2010. Available at http://europe.newsweek.com/why-antidepressants-are-no-better-placebos-71111?rm=eu. Accessed on 3 March 2017.

Kirsch I. The Emperor's New Drugs: Exploding The Antidepressant Myth. Basic Books: New York, NY, 2010.

Angell M. The Epidemic of Mental Illness: Why? New York Review of Books. June 23, 2011. Available at http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2011/06/23/epidemic-mental-illness-why/. Accessed on 3 March 2017.

CBS 60 Minutes. Treating Depression: Is There a Placebo Effect? CBS 60 Minutes 19 February 2012. Available at http://www.cbsnews.com/news/treating-depression-is-there-a-placebo-effect/ Accessed on 3 March 2017.

Greenberg RP, Bornstein RF, Zborowski MJ, Fisher S, Greenberg MD. A meta-analysis of fluoxetine outcome in the treatment of depression. J Nerv Ment Dis 1994; 182: 547–551.

Barth M, Kriston L, Klostermann S, Barbui C, Cipriani A, Linde K. Efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse events: meta-regression and mediation analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry 2016; 208: 114–119.

Rabinowitz J, Werbeloff N, Mandel FS, Menard F, Marangell L, Kapur S. Initial depression severity and response to antidepressants v. placebo: patient-level data analysis from 34 randomised controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry 2016; 209: 427–428.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration CfDEaR: Paxil NDA 020031, Statistical Review. 23 October 1992. Available at http://digitalcommons.ohsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1025&context=fdadrug Accessed 03-03-2017.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration CfDEaR: Celexa NDA 20-822, Medical Review (part 2). 26 May 1998; Available at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/98/020822a_medr_P2.pdf. Accessed on 3 March 2017.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration CfDEaR: Paxil CR NDA 20-936, Statistical Review. 18 June 1998. Available at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/99/20-936_Paxil_statr.pdf. Accessed on 3 March 2017.

Ferguson JM. SSRI antidepressant medications: adverse effects and tolerability. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 3: 22–27.

Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR, Marshall MB. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: has the gold standard become a lead weight? Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161: 2163–2177.

Hieronymus F, Emilsson JF, Nilsson S, Eriksson E. Consistent superiority of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors over placebo in reducing depressed mood in patients with major depression. Mol Psychiatry 2016; 21: 523–530.

Hieronymus F, Nilsson S, Eriksson E. A mega-analysis of fixed-dose trials reveals dose-dependency and a rapid onset of action for the antidepressant effect of three selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Transl Psychiatry 2016; 6: e834.

Nilsson ME, Koke SC. Defining treatment-emergent adverse events with the medical dictionary for regulatory activities (MedDRA). Drug Inf J 2001; 35: 1289–1299.

Letemendia FJ, Harris AD. The influence of side-effects on the reporting of symptoms. Psychopharmacologia 1959; 1: 39–47.

Rabkin JG, Markowitz JS, Stewart J, McGrath P, Harrison W, Quitkin FM et al. How blind is blind? Assessment of patient and doctor medication guesses in a placebo-controlled trial of imipramine and phenelzine. Psychiatry Res 1986; 19: 75–86.

Margraf J, Ehlers A, Roth WT, Clark DB, Sheikh J, Agras WS et al. How “blind” are double-blind studies? J Consult Clin Psychol 1991; 59: 184–187.

Petkova E, Quitkin FM, McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Klein DF. A method to quantify rater bias in antidepressant trials. Neuropsychopharmacology 2000; 22: 559–565.

Liberman R. A criticism of drug therapy in psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4: 131–136.

Klerman GL, Cole JO. Clinical pharmacology of imipramine and related antidepressant compounds. Pharmacol Rev 1965; 17: 101–141.

Thomson R. Side effects and placebo amplification. Br J Psychiatry 1982; 140: 64–68.

Moncrieff J, Wessely S, Hardy R. Active placebos versus antidepressants for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; CD003012.

Anderson IM. Antidepressant quandaries (letter). Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173: 181–182.

Quitkin FM, Rabkin JG, Gerald J, Davis JM, Klein DF. Validity of clinical trials of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 327–337.

Kuhn R. The treatment of depressive states with G 22355 (imipramine hydrochloride). Am J Psychiatry 1958; 115: 459–464.

Lopez-Munoz F, Alamo C. Monoaminergic neurotransmission: the history of the discovery of antidepressants from 1950s until today. Curr Pharm Des 2009; 15: 1563–1586.

Scott AI, Perini AF, Shering PA, Whalley LJ. In-patient major depression: is rolipram as effective as amitriptyline? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1991; 40: 127–129.

Vestergaard P, Gram LF, Kragh-Sorensen P, Bech P, Reisby N, Bolwig TG. Therapeutic potentials of recently introduced antidepressants. Danish University Antidepressant Group. Psychopharmacol Ser 1993; 10: 190–198.

Ansseau M, Darimont P, Lecoq A, De Nayer A, Evrad JL, Krémer P et al. Controlled comparison of nefazodone and amitriptyline in major depressive inpatients. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994; 115: 254–260.

Lapierre YD, Browne M, Oyewumi K, Sarantidis D. Alprazolam and amitriptyline in the treatment of moderate depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1994; 9: 41–45.

Yevtushenko VY, Belous AI, Yevtushenko YG, Gusinin SE, Buzik OJ, Agibalova TV. Efficacy and tolerability of escitalopram versus citalopram in major depressive disorder: a 6-week, multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled study in adult outpatients. Clin Ther 2007; 29: 2319–2332.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Swedish Research Council, AFA Insurance, Bertil Hållsten’s Foundation, Söderberg’s Foundation, the Sahlgrenska University Hospital and the Swedish Brain Foundation. H Lundbeck and GSK provided the individual patient data used in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

FH has received speaker’s fees from Servier. EE has previously been on advisory boards and/or received speaker’s honoraria and/or research grants from Eli Lilly, Servier, GSK and H Lundbeck. SN and AL declare no potential conflict of interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if thematerial is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hieronymus, F., Lisinski, A., Nilsson, S. et al. Efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the absence of side effects: a mega-analysis of citalopram and paroxetine in adult depression. Mol Psychiatry 23, 1731–1736 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.147

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.147

This article is cited by

-

Are the results of open randomised controlled trials comparing antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia biased? Exploratory meta- and subgroup analysis

Schizophrenia (2024)

-

Serotonin modulates asymmetric learning from reward and punishment in healthy human volunteers

Communications Biology (2022)

-

Great Expectations: recommendations for improving the methodological rigor of psychedelic clinical trials

Psychopharmacology (2022)

-

Expectancy effects on serotonin and dopamine transporters during SSRI treatment of social anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial

Translational Psychiatry (2021)

-

Do side effects of antidepressants impact efficacy estimates based on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale? A pooled patient-level analysis

Translational Psychiatry (2021)