Abstract

Acute and chronic alcohol exposure significantly affect behavior but the underlying neurobiological mechanisms are still poorly understood. Here, we used functional connectivity density (FCD) mapping to study alcohol-related changes in resting brain activity and their association with behavior. Heavy drinkers (HD, N=16, 16 males) and normal controls (NM, N=24, 14 males) were tested after placebo and after acute alcohol administration. Group comparisons showed that NM had higher FCD in visual and prefrontal cortices, default mode network regions and thalamus, while HD had higher FCD in cerebellum. Acute alcohol significantly increased FCD within the thalamus, impaired cognitive and motor functions, and affected self-reports of mood/drug effects in both groups. Partial least squares regression showed that alcohol-induced changes in mood/drug effects were associated with changes in thalamic FCD in both groups. Disruptions in motor function were associated with increases in cerebellar FCD in NM and thalamus FCD in HD. Alcohol-induced declines in cognitive performance were associated with connectivity increases in visual cortex and thalamus in NM, but in HD, increases in precuneus FCD were associated with improved cognitive performance. Acute alcohol reduced 'neurocognitive coupling', the association between behavioral performance and FCD (indexing brain activity), an effect that was accentuated in HD compared with NM. Findings suggest that reduced cortical connectivity in HD contribute to decline in cognitive abilities associated with heavy alcohol consumption, whereas increased cerebellar connectivity in HD may have compensatory effects on behavioral performance. The results reveal how drinking history alters the association between brain FCD and individual differences in behavioral performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alcohol is the most widely used addictive substance worldwide. Although it is debatable whether moderate drinking offers any health benefits,1 the deleterious effects of excessive alcohol use on the brain and behavior are well recognized.2 There has been a challenge to characterize the effects of acute and chronic alcohol exposure on the association between resting brain activity and behavior. Studies measuring resting cerebral blood flow (CBF) during alcohol intoxication have shown that CBF increases particularly within the frontal and temporal cortices, which in part reflect ethanol-induced vasodilatation.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 In contrast, studies measuring cerebral metabolic rate of glucose (CMRglc) during alcohol intoxication have shown reductions in glucose metabolism throughout the brain that were most pronounced in the visual cortex and cerebellum.11, 12, 13, 14 The opposite effects of acute alcohol on CBF and CMRglc, on one hand, reflect alcohol’s vasoactive effects15 and, on the other hand, reflect the use of alternative energy sources for brain metabolism (for example, alcohol’s metabolite acetate).16, 17 Specifically, recent work has suggested that biphasic vasoactive properties of alcohol15 may disrupt the coupling between neuronal activity and CBF.16 In relation to the association between CMRglc and brain activity during intoxication, our work has suggested that alcohol-induced decreases in glucose metabolism are concurrent with brain-wide increases in acetate metabolism.17 The acetate content in plasma increases during alcohol intoxication. Thus, we have interpreted alcohol-induced decreases in glucose metabolism to reflect the preference of glial cells for acetate as an energy source.18 This effect appears to be accentuated in heavy alcohol drinkers and in alcoholics.11, 13 CBF and CMRglc measures seem to reveal a more consistent pattern for the effect of chronic drinking on the resting brain. Relative to light drinkers, heavy drinkers (HD) show lower resting CBF,19 particularly within the frontal lobe,20 and lower resting CMRglc, possibly due to higher acetate metabolism.13, 21, 22 In summary, it is difficult to determine the extent to which effects of acute and chronic alcohol exposure on CBF and CMRglc reflect exclusive changes in neuronal activity.

Alternative measures of resting brain activity include functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) resting-state functional connectivity, which estimates synchronous changes in blood oxygenation level between and within brain regions at rest.23 Inter- and intra-regional resting-state fMRI connectivity reflect synchronous oscillations in neuronal activity24, 25, 26 that are largely insensitive to vasodilation,26 and are also unlikely to be affected by brain-wide changes in metabolic supply. Moreover, prior research has shown that measures of resting-state functional connectivity are sensitive to effects of acute and chronic alcohol exposure on the brain. Specifically, alcohol intoxication has been associated with increases in connectivity between the brainstem and somatosensory network, and within the visual network,27 as well as time-varying changes in connectivity within the default mode network.28 As for chronic exposures, the frequency of alcohol use has been associated with connectivity in the dorsal default mode network,29 and alcoholics show weaker within- (including the default mode network) and between-network connectivity.30, 31

Up to now, fMRI resting-state research in alcohol and alcoholism has been mostly limited to pre-defined resting-state networks or seed-voxel correlations. Recently, functional connectivity density (FCD) mapping has been proposed as a voxel-wise measure of resting-state functional connectivity.32 Specifically, this approach provides measures of local FCD (lFCD; size of the local cluster of correlated voxels) and global FCD (gFCD; the total number of correlated voxels) for each voxel. Studies in healthy controls have suggested that lFCD and gFCD account for up to 70% of glucose demand in the resting brain indicating that they serve as an index of brain activity at rest.33, 34 To mitigate confounds from CBF and CMRglc measures, our goal here was to use lFCD and gFCD as alternative measures to assess the effects of acute and chronic alcohol consumption on activity of the brain at rest. Specifically, lFCD and gFCD indices were compared in HD and light drinkers in placebo and alcohol intoxication conditions.

We hypothesized that voxel-wise FCD analysis will show effects in regions that are most sensitive to acute or chronic alcohol effects such as the cerebellum,3, 35 thalamus,36 frontal cortex37 and limbic system.38, 39 As alcohol intoxication is associated with multiple behavioral domains,40, 41 here, we investigated the association between brain regions showing significant alcohol-related changes in FCD and behavioral measures in three categories: mood/drug effects, motor and cognitive functions. Specifically, we predicted that alcohol-induced changes in mood/drug effects would be concurrent with connectivity changes in thalamus and limbic brain regions showing FCD effects.42, 43 We predicted that alcohol-related motor effects (for example, balance and coordination) would be concurrent with connectivity changes in cerebellar regions showing alcohol-related FCD effects.44, 45 For cognitive effects of alcohol, a recent meta-analysis reported that multiple cognitive domains46 are affected in alcoholics including executive functions that rely on prefrontal cortex (PFC),47 and visuospatial abilities that rely on occipital and parietal regions.45 Hence, we hypothesized that alcohol effects on cognitive performance would be associated with FCD effects in PFC48 and occipital and parietal regions.49 It has been increasingly recognized that the cerebellum also contributes to cognitive functions and that cerebellar damage contributes to cognitive deficits in alcoholics.50 Accordingly, we hypothesized an association between FCD effects in cerebellum and alcohol effects on cognitive performance. Finally, we assessed the effects of alcohol administration on the overall neurocognitive coupling: the association between behavioral performance and FCD in regions with significant voxel-wise alcohol-related effects. We hypothesized that acute alcohol would reduce neurocognitive coupling if FCD changes predominantly reflect alcohol-induced effects on the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters.51, 52

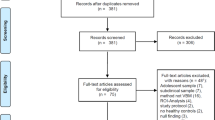

Materials and Methods

Participants

We studied two groups of participants: 16 HD (age: mean=34.6 years, s.d.=9.70 years; 16 males) and 24 normal controls (NM; age: mean=32.5 years, s.d.=6.39 years; 14 males). Out of 48 planned participants for both groups, these subjects completed required MRI sessions. We predicted at α=0.05 and 80% power, this sample size would allow to detect large group and condition effects on FCD (Cohen’s d=0.9, r=0.5). The inclusion criterion for HD was five or more drinks a day on three or more occasions per week. The HD reported their last use of alcohol within 3 days of the MRI scans. To maximize group differences, for NM group, we included participants with light drinking history of no more than one drink a day. Because we did not want to give alcohol for the first time to an individual without any alcohol experience, NM also had to have prior experience with alcohol. Exclusion criteria were: (i) urine positive for psychotropic drugs; (ii) present or past history of dependence on alcohol or other drugs of abuse (except nicotine and allowed diagnosis of alcohol abuse though not dependence for HD); (iii) present or past history of neurological or psychiatric disorder; (iv) use of psychoactive medications in the past month (that is, opiate analgesics, stimulants, sedatives); (v) use of prescription (non-psychiatric) medication(s), that is, antihistamines; (vi) medical conditions that may alter cerebral function; (vii) cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and (viii) history of head trauma with loss of consciousness of more than 30 min. Signed informed consents were obtained from the subjects prior to participation, approved by the Committee on Research in Human Subjects at Stony Brook University (IRBNet ID: 137462, CORIHS ID: 20090792).

Alcohol and placebo administration

Each participant was tested on separate days (maximum 3 days apart) to assess the effects of alcohol (ALC) and placebo (PLC). The order of ALC and PLC conditions was randomly assigned across subjects (single blinded). Subjects drank alcohol (0.75 g kg−1 mixed in a caffeine-free diet soda) or placebo (caffeine-free diet soda) beverages within a 20-min period under blind conditions. For this purpose, we used a specialized drinking container with an alcohol-containing lid that provided the smell of alcohol and delivered the same volume of liquid in both conditions. The MRI scan started between 90 and 120 min of ALC or PLC administration. The alcohol dose (0.75 g kg−1) was approximately equivalent to three drinks for a 50 kg person and was within the range consumed by social drinkers.53 Blood alcohol concentration levels were measured prior to the fMRI scan using a standard enzymatic assay.54 The average blood alcohol concentration across participants was 0.62 mg ml−1 (s.d.=0.27 mg ml−1) at the beginning of the MRI scanning session.

Behavioral measures

Self-reports of mood and drug effects, motor evaluations and cognitive tests were performed to assess the effects of alcohol or placebo on behavior in NM and HD. Measures were obtained prior to each MRI session, approximately 90 min after placebo or alcohol administration (30 min prior to MRI session). Self-report mood/drug effects were scored by the subject from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely) for feelings of stimulated, sedated, self-confident, social, irritable, dizzy, high, anxious, pleasant, alcohol desire, control, intoxicated and restless. Motor function evaluated gait (time and errors), standing on one leg (errors), Romberg (time and errors) and rhythm (time and errors) tasks.55 Cognitive evaluation was made by staff credentialed to perform psychological assessments and included the Stroop (neutral, congruent and incongruent), Symbol Digit Modalities test and Word Association tasks.55 Behavioral data on two subjects (one NM and one HD) were not available. The between-subject factor of Groups and within-subject factor of Alcohol were modeled in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) while using smoking history and gender as covariates. We minimized multiplicity of comparisons by grouping the behavioral measures into three categories: mood and drug effects, motor, and cognitive performance (see partial least squares (PLS) regression for further information).

MRI data acquisition

Subjects underwent fMRI in a 4-tesla Varian/Siemens MRI scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) using a T2*-weighted single-shot gradient-echo planar imaging sequence (echo time/repetition time, 20/1600 ms; 4-mm slice thickness; 1-mm gap; 33 coronal slices; 3.1 × 3.1 mm in-plane resolution). Participants were instructed to remain silent, motionless and awake with eyes open during the 5-min resting-state scan with presentation of a fixation cross.

fMRI data preprocessing

All fMRI time series were realigned and normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute space with 3-mm isotropic voxels in SPM8 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK).56 There were no significant main effects of Group or Alcohol, or a significant interaction effect on estimates of subjects’ motion (P>0.05) for mean frame-wise displacement calculated from six translation and rotation parameters obtained from the realignment process. fMRI time points that were severely affected by motion were removed using a 'scrubbing' approach.57 Specifically, in each subject/session, less than 4% of time points were removed with a root mean square signal change (that is, DVARs) threshold of 5% and a framewise displacement (that is, FD) threshold of 0.5 mm. Remaining motion effects on fMRI time series were regressed out using the six translation and rotation regressors. Voxels with poor temporal signal-to-noise (<50) were eliminated, and band-pass temporal filtering (0.01–0.10 Hz) was used to remove magnetic field drifts of the scanner and to minimize the effects of physiologic noise on the high-frequency components. The effects of unwanted fluctuations within the white matter and cerebrospinal fluid were excluded from the analysis by using a gray matter mask (N=57 713).

Local FCD (lFCD)

The Pearson correlation was used to assess the strength of functional connectivity, Cij, between voxels i and j. Consistent with prior FCD studies,32, 46 a positive correlation threshold of r=0.6 (sufficient to Bonferroni correct for the number of correlations performed in the whole brain, P<0.05) was used to compute the binary connectivity coefficients, aij=1 (if Cij>0.6) or aij=0 (if Cij⩽0.6). The local FCD (or 'local degree') for voxel i was computed as the size of a continuous cluster of voxels with aij=1, that are connected by surface. A 'growing' algorithm was used for time-efficient estimation of lFCD.32

Global FCD (gFCD)

The gFCD, also called 'degree',58, 59 was calculated as the total number of edges for voxel i, that is, significant correlations (at Cij>0.6) between voxel i and all voxels:60

Statistical parametric mapping

SPM8 was used to perform voxel-wise analyses on FCD indices. Gender and smoking status were entered as covariates to control for differences between the groups in these variables. A flexible factorial design was used to model the between-subject factor of Group (NM vs HD) and the within-subject factor of Alcohol (PLC and ALC). Regions of interest (ROIs) were identified after familywise error (FWE) correction for multiple comparisons at the cluster level correction approach (PFWE<0.05) with a minimum cluster size of k=75 and a cluster forming threshold of P<0.005.

Neurocognitive coupling analysis

We define 'neurocognitive coupling' as the overall association between individual differences in regional resting activity (indexed here by ROI FCD) and individual differences in behavioral performance. Specifically, a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance was performed in MATLAB to assess the effects of Group and Alcohol on the distribution mean of Fisher’s z-transformed correlations between functional ROIs that showed Group or Alcohol effects and behavioral measures that showed Group or Alcohol effects. This analysis was also repeated for a set of a priori anatomical ROIs (Supplementary Figure 3).

Partial least squares regression

A PLS regression analysis was performed in MATLAB to reduce the dimensionality of data and consequently the number of comparisons.61, 62 Whereas other approaches such as principal component analysis find components that maximize the variance within a set of variables, PLS regression finds components in the independent variables based on the criteria of maximizing the amount of variance accounted for in both dependent and independent variables. For each behavioral category (that is, mood/drug effects, motor and cognitive performance), the goal of the PLS regression analysis was to find a linear combination of ROI FCDs (component scores) that maximizes the amount of variance accounted for in the included behavioral test as well as ROI FCDs. The number of components selected from ROI FCDs was limited to 1 for each behavioral category. For significance testing of the contribution of each ROI FCD to component scores, a permutation approach was used (N=100 000) to extract the null distribution of component loadings. All the P-values for PLS regression analysis are reported for a two-tailed test (that is, considering positive and negative loadings).

Results

Behavioral

There was a main effect of Group (Supplementary Table 1, P<0.05, Bonferroni) for self-reports of irritability (HD>NM), restlessness (HD>NM) and alcohol desire (HD>NM). There were also main effects of Group (Supplementary Table 1, P<0.05, Bonferroni) in all cognitive measures, with HD showing lower performance relative to NM on Stroop, Symbol Digit Modalities test and Word Association tests. There was a main effect of Alcohol (Supplementary Table 2, P<0.05, Bonferroni) for self-reports of sedated (ALC>PLC), dizzy (ALC>PLC), high (ALC>PLC), pleasant (ALC>PLC) and intoxication (ALC>PLC). Alcohol also reduced performance on tests of motor coordination and balance (Supplementary Table 2, P<0.05, Bonferroni). In addition, acute alcohol affected cognitive performance, decreasing scores on Stroop, Symbol Digit Modalities test and Word Association tests. No behavioral measure showed a significant interaction between Group and Alcohol factors (Supplementary Table 3, P>0.05).

Local FCD (lFCD)

Consistent with our prior findings,32 the spatial distribution of average lFCD across all subjects for PLC revealed main hubs within the posterior cingulate, ventral precuneus, inferior parietal cortex, cuneus, anterior PFC and cerebellum (Supplementary Figure 1). The flexible factorial analysis revealed a main effect of Group (HD vs NM) showing decreased connectivity in HD within the PFC, calcarine, posterior cingulate, precuneus and thalamus, and increased connectivity in cerebellum (Figures 1a and b, PFWE<0.05, Table 1). The thalamus cluster included the medial dorsal nucleus (MDN) and ventral lateral nucleus (VLN) with the statistical peak located at the MDN (PFWE<0.05). There was a main effect of Alcohol within the thalamus (Table 1 and Figure 1c, PFWE<0.05), wherein alcohol intoxication increased thalamus lFCD relative to PLC (PFWE<0.05). Similar to the effect of Group, the thalamic nuclei included MDN and VLN, and the statistical peak was located at the VLN. Average lFCD for each group and condition for the ROIs, showing significant Group and Alcohol effects (PFWE<0.05) are summarized in Figure 2. For whole brain lFCD, there were no significant main effects of Group (P=0.593) or Alcohol (P=0.183), or a significant interaction effect (P=0.183) (Supplementary Table 4). The Thalamus (MDN) ROI corroborated a significant effect of Alcohol (ALC>PLC, Supplementary Table 4, P<0.0001), and Thalamus (VLN) ROI corroborated a significant effect of Group (HD<NM, Supplementary Table 4, P<0.0001).

Main effects of Group and Alcohol for local functional connectivity density (lFCD). (a) Left (L) and right (R) views of the effect of Group (Heavy Drinkers (HD)<Normal Controls (NM), PFWE<0.05) superimposed on lateral and medial views of the cerebral surface. (b) Posterior (P) and anterior (A) views of the effect of Group (HD>NM, PFWE<0.05) only in the cerebellum. (c) Main effect of Alcohol for lFCD. Left (L) and right (R) views of the effect of Alcohol within the Thalamus ventral lateral nucleus (VLN) cluster (Alcohol (ALC)>Placebo (PLC), PFWE<0.05).

Effects of Group and Alcohol on local functional connectivity density (lFCD) ROIs. Group average lFCD of the voxels showing main effects of Group (a–e, g) and Alcohol (f) as well as the whole brain (h). The error bars show group standard deviation.

Global FCD (gFCD)

Consistent with our prior findings,60 the spatial distribution of average lFCD across all subjects for PLC revealed main hubs within visual cortex, postcentral gyrus, precuneus, inferior parietal cortex, temporal lobe and cerebellum (Supplementary Figure 2). For gFCD, the effects of Group overlapped with those of lFCD but were limited to a smaller set of regions (Table 2 and Figure 3). Specifically, gFCD was lower within calcarine and thalamus and higher within cerebellum in HD relative to NM (PFWE<0.05). Similar to lFCD, there was a main effect of Alcohol for gFCD within thalamus (Table 2 and Figure 3, PFWE<0.05), including MDN and VLN nuclei, and midbrain with a statistical peak located at VLN showing increased gFCD during alcohol intoxication. Average gFCD for each group and condition for ROIs showing significant Group and Alcohol effects are summarized in Figure 4. For whole brain gFCD, there were no significant main effects of Group (P=0.760) or Alcohol (P=0.334), or a significant interaction effect (P=0.102, Supplementary Table 4). The 10 FCD ROIs showing significant Group or Alcohol effects (7 from the lFCD and 3 from gFCD results) were used for the analyses of associations between behavior and brain connectivity (see Table 3 for the list of FCD ROIs).

Main effect of Group and Alcohol for global functional connectivity density (gFCD). (a) Left (L) and right (R) views of the effect of Group in calcarine (HD<NM, PFWE<0.05) superimposed on lateral and medial views of the cerebral surface. (b) Posterior (P) and anterior (A) views of the effect of group (HD>NM, PFWE<0.05) only in the cerebellum. (c) Main effect of alcohol for gFCD. Left (L) and right (R) views of the effect of Alcohol within the thalamus (ALC>PLC, PFWE<0.05).

Effects of Group and Alcohol on global functional connectivity density (gFCD) ROIs. Group average gFCD of the voxels showing main effects of Group (a, c) and Alcohol (b) as well as the whole brain (d). The error bars show group standard deviation.

Between-subject correlations in FCD

We ran an additional analysis to examine the correlation structure across subjects between the 10 FCD ROIs with significant main effects of Group or Alcohol for lFCD or gFCD indices (see Table 3). The results are summarized for each group and condition in Figure 5. Below diagonal elements show pairwise correlations between ROIs while controlling for gender and smoking. Above diagonal elements show pairwise partial correlations between ROIs while controlling for effect of other ROIs as well as gender and smoking. Overall alcohol reduced the association between ROI FCDs in both groups (see Supplementary Results). We performed a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance to assess effects of Group and Alcohol on the distribution mean of 45 Fisher’s z-transformed below-diagonal correlations (that is, pairwise correlations between 10 ROI FCDs; Figures 6a–d). There was a significant effect of Alcohol (meanPLC=0.38, s.d.PLC=0.36; meanALC=0.28, s.d.ALC=0.45; F(1, 44)=19.76, P=0.03) but no significant effect of Group or interaction between Alcohol and Group factors (P>0.05). A similar analysis on the above diagonal elements (partial correlations, Figures 6a–d) did not show any significant Group, Alcohol or interaction effects (P>0.05). We also assessed the significance of changes in specific correlation coefficients between PLC and ALC conditions for each group (Figures 5e and f). In HD, the most pronounced changes were increases and decreases of correlations between Thalamus (VLN) gFCD and the rest of ROIs (Cerebellum, Precuneus, Thalamus (MDN) and Thalamus (VLN) lFCDs, P<0.005, Figure 5f), whereas in NM, Calcarine gFCD correlations underwent most changes between PLC and ALC conditions (Cerebellum lFCD and Thalamus (VLN) gFCD, P<0.005, Figure 5e and Supplementary Results).

Between-subject correlation matrix (10 × 10) between 7 local functional connectivity density (lFCD) and 3 global functional connectivity density (gFCD) ROIs across subjects in (a) normal controls (NM) in placebo (PLC) condition, (b) heavy drinkers (HD) in PLC condition, (c) NM in alcohol (ALC) condition and (d) HD in ALC condition. Full correlations (controlling for gender and smoking) are shown below diagonal (black line) and partial correlations (removing effect of other ROIs and controlling for gender and smoking) are shown above diagonal. The colorbars in (a–d) indicate that positive correlations are shown in red-yellow and negative correlations are shown in blue-green. The z-score of the change in correlation are depicted in (e) for NM and (f) for HD. The colorbars in (e–f) indicate that positive changes (indexed by z-scores) are shown in red-yellow and negative correlations are shown in blue-green.

Neurocognitive coupling analysis on local functional connectivity density (lFCD) and global functional connectivity density (gFCD) ROIs. (a–b) 10-bin histogram of z-transformed correlations between the 18 behavioral measures showing main effects of Group or Alcohol and the 10 ROI FCDs showing main effects of Group or Alcohol in normal controls (NM) (a) and heavy drinkers (HD) (b) in placebo (PLC) condition (blue) and alcohol (ALC) condition (red) as well as normal fits to the corresponding histograms in dark red and dark blue. (c–h) Matrices of P-values estimated from a permutation test on the PLS regression component loadings, showing the strength of association between each ROI FCD and a behavioral category for NM in PLC (c), HD in PLC (d), NM in ALC (e), HD in ALC (f), NM for changes from ALC to PLC (g) and HD for changes from ALC to PLC (h). Gray-scale bars indicate the range of P-values (range: 0–0.1) shown in (c–h).

Neurocognitive coupling

We estimated Pearson’s correlation coefficients between performance on the 18 behavioral tasks with significant Group or Alcohol effects (Table 3) and FCD of the 10 ROIs with significant Group or Alcohol effects (Table 3), for each group and condition (Supplementary Tables 5–8) as well as correlations between alcohol-induced changes in ROI FCDs and changes in behavioral performance in each group (Supplementary Tables 9 and 10). A two-way repeated measures analysis of variance on the Fisher’s z-transformed correlations presented in Supplementary Tables 5–8 showed (Figures 6a and b) a significant main effect of Alcohol (F(1, 179)=19.76, P<0.0001) and a significant interaction between Alcohol and Group on the neurocognitive coupling (F(1, 179)=5.32, P=0.022). However, the effect of Group was not significant (F(1, 179)=0.68, P=0.41). The results indicated that ALC relative to PLC reduced the neurocognitive coupling in both groups (meanPLC=0.09, s.d.PLC=0.31; meanALC=0.01, s.d.ALC=0.28). The interaction effect indicated that relative to PLC, the reduction in neurocognitive coupling after alcohol was more pronounced in HD (meanPLC=0.12, s.d.PLC=0.36, meanALC=−0.01, s.d.ALC=0.23; Figure 6b) than in NM (meanPLC=0.06, s.d.PLC=0.26, meanALC=0.01, s.d.ALC=0.22; Figure 6a). Similar neurocognitive coupling results with a significant effect of Alcohol and a significant Group and Alcohol interaction were obtained (see Supplementary Figure 3) when we used four a priori ROIs with known sensitivity to acute or chronic alcohol effects.3, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39

Associations between behavior and FCD

PLS regressions (see Materials and Methods) showed that in NM in PLC condition (Figure 6c), ROI FCDs accounted for 7%, 23% and 5% of variance in mood/drug effects, motor and cognitive tasks, respectively. For the mood/drug factor, Calcarine lFCD (P=0.04), Cerebellum lFCD (P=0.02) and Cerebellum gFCD (P=0.03); for the motor factor, Cerebellum lFCD (P=0.005), Cerebellum gFCD (P=0.01) and Thalamus (MDN) lFCD (P=0.04); and for the cognitive factor, Posterior Cingulate lFCD (P=0.03) and Thalamus (MDN) lFCD (P=0.02) significantly contributed to predicting individual differences.

In NM in ALC condition (Figure 6e), ROI FCDs accounted for 10%, 11% and 17% of variance in mood/drug effects, motor and cognitive tasks, respectively. For the mood/drug factor, Calcarine lFCD (P=0.02), Posterior Cingulate lFCD (P=0.002) and Thalamus (MDN) lFCD (P=0.06); for the motor factor, Thalamus (MDN) lFCD (P=0.002) and Thalamus (VLN) lFCD (P=0.02); and for the cognitive factor, Calcarine gFCD (P=0.05) significantly contributed to predicting individual differences.

In HD in PLC condition (Figure 6d), ROIs FCDs accounted for 13%, 25% and 26% of variance in mood/drug effects, motor and cognitive tasks, respectively. For the mood/drug factor, Thalamus (MDN) lFCD (P=0.03); for the motor factor, Cerebellum lFCD (P=0.002) and Cerebellum gFCD (P=0.005); and for the cognitive factor, PFC lFCD (P=0.05), Calcarine gFCD (P=0.05), Cerebellum gFCD (P=0.02) and Thalamus (VLN) gFCD (P=0.04) significantly contributed to predicting individual differences.

In HD in ALC condition (Figure 6f), ROIs FCDs accounted for 16%, 22% and 32% of variance in mood/drug effects, motor and cognitive tasks, respectively. For the mood/drug factor, Calcarine lFCD (P=0.05); for the motor factor, Cerebellum lFCD (P=0.05) and PFC lFCD (P=0.03); and for the cognitive factor Cerebellum gFCD (P=0.05) significantly contributed to predicting individual differences.

In NM, PLS regression of alcohol-induced changes (that is, ALC-PLC) in behavioral scores on changes in ROI FCDs showed that changes in ROI FCDs accounted for 9%, 15% and 10% of variance in mood/drug effects, motor and cognitive score changes, respectively (Figure 6g). Alcohol-induced changes in the mood/drug factor were associated with changes in Thalamus (VLN) lFCD (P=0.04) and Thalamus (VLN) gFCD (P=0.06); changes in motor factor were associated with changes in Cerebellum gFCD (P=0.03); and changes in cognitive factor were associated with changes in Calcarine gFCD (P<0.001) and Thalamus (VLN) gFCD (P=0.03). In HD (Figure 6h), changes in ROI FCDs accounted for 9%, 14% and 36% of variance in mood/drug effects, motor and cognitive score changes, respectively. Changes in the mood/drug factor were associated with changes in Thalamus (VLN) lFCD (P=0.04) and Thalamus (VLN) gFCD (P=0.01); changes in motor factor were associated with changes in Thalamus (MDN) lFCD (P=0.06); and changes in cognitive factor were associated with changes in Precuneus lFCD (P=0.02).

Discussion

Here, we document significant regional effects of acute and chronic alcohol use on FCD indices that were associated with changes in mood/drug effects, motor and cognitive measures. We found effects of both Group and Alcohol on the thalamus (see Tables 1 and 2), which included the ventral lateral (VLN) and medial dorsal (MDN) nuclei. The VLN receives inputs from cerebellum and interacts with motor-related cortical areas,63 whereas the MDN is mostly associated with the PFC and has been implicated in memory, attention, mood and reward.64, 65 In both groups, alcohol-induced changes in thalamus FCDs were associated with changes in mood/drug effects (Figures 6g and h), which is consistent with the known functional role of MDN. The thalamus lFCDs also contributed to predicting motor performance in both PLC and ALC conditions in NM (P<0.05, Figures 6c and d). In HD, it was the changes in motor performance from PLC to ALC that were associated with changes in Thalamus (MDN) lFCD (P=0.06, Figure 6h). The effect of thalamus connectivity on motor function in NM (both PLC and ALC conditions) is consistent with the contribution of VLN (the thalamus nuclei relaying motor information to the cortex) in motor performance, but in HD, the association between alcohol-induced decline in motor performance and changes in thalamus connectivity (particularly VLN) might reflect unsuccessful compensatory activity in the thalamus (Figure 6e). In contrast, in NM, decline in motor performance from PLC to ALC was associated with changes in cerebellum connectivity (P=0.03, Figure 6e). These findings indicate that different parts of the cerebellar-thalamic circuit contribute to alcohol-induced changes in motor performance in NM versus HD.

Findings of increased connectivity in thalamus during intoxication could explain why the thalamus is one of the least sensitive regions to the decreases in glucose metabolism triggered by acute alcohol,13, 17 wherein alcohol-induced increases in thalamic connectivity lead to increases in metabolic needs. The sensitivity of the thalamus to acute alcohol is also consistent with prior findings showing high uptake of alcohol in the thalamus of non-human primates.66 The thalamic nuclei that were affected by alcohol, namely the VLN and MDN, are nuclei that receive direct projection from DA neurons in VTA67, 68 and hence their activation might reflect alcohol-induced dopaminergic signaling. In fact, we had previously shown that DA increases triggered by methylphenidate were associated with metabolic changes in the thalamus, which were significantly increased in controls but not in alcoholics.69 Our findings also showed that acute alcohol significantly increased global connectivity in the midbrain as a part of a gFCD cluster centered at the thalamus (Table 2), which is where DA neurons are located.70 This effect is consistent with the influence of alcohol on DA signaling.71 Though the extent of influence of alcohol-induced vasodilation on resting connectivity is not understood, we did not find significant voxel-wise effects of acute alcohol in regions with pronounced alcohol-induced vasodilation such as frontal and temporal cortices.3, 6, 7, 8, 9

We also found significant effects of chronic alcohol on the thalamus (Table 1, Figure 2), which showed significantly higher connectivity in NM than HD. In addition, NM had higher connectivity in calcarine (visual cortex), PFC, posterior cingulate and precuneus, whereas HD had higher connectivity in cerebellum than NM. Both groups in PLC showed a positive association between cognitive performance and higher thalamic connectivity (Figure 6, Supplementary Tables 5 and 7). However, in NM, alcohol-induced declines in cognitive performance (which included tests of inhibitory control, executive function and visuospatial attention) were associated with increases in connectivity in Thalamus (VLN) gFCD and Calcarine gFCD (Figure 6g, Supplementary Table 9). In contrast, alcohol-induced increases in precuneus connectivity (Supplementary Table 4) were associated with changes in cognitive performance in HD, suggesting that connectivity increases in precuneus might have a compensatory role for higher cognitive abilities (Supplementary Table 10).

The cerebellum is one of the most sensitive brain regions to the deleterious effects of chronic alcohol.72 Thus, higher FCD in cerebellum in HD might reflect compensation to overcome impairments associated with repeated alcohol use. In fact, PLS regression showed that in both groups, Cerebellum FCDs were the most significant predictors of motor function (P<0.01, Figures 6c and d) in the PLC condition. However, only in HD, higher cerebellum FCD predicted better cognitive performance in both PLC and ALC conditions (Figures 6d and f, Supplementary Table 8). Yet, higher cerebellum FCDs in both groups were associated with more motor errors but faster time on task, indicating a speed-accuracy trade-off (Supplementary Tables 5 and 7). The results suggest that higher cerebellum FCD might be a compensatory response, but only for cognitive performance (for example, conflict resolution and inhibition) in HD.

In HD, we identified two categories of changes in FCD: decreases in cortical and thalamic FCD and increases in cerebellar FCD. This group also showed markedly lower performance in a range of cognitive tasks. PLS regression showed that a large range of ROI FCDs contribute to cognitive performance in this group in PLC (Figure 6c). Furthermore, higher connectivity in these regions was positively correlated with task performance (Supplementary Table 7), leading to the conclusion that the lower the connectivity in these ROIs, the lower the cognitive performance in HD. Though there was no group difference in motor function between HD and NM, PLS regression showed significant cerebellar contribution in motor performance in HD (Figure 6c), suggesting a compensatory role of increased cerebellar FCD in HD.

Acute and chronic alcohol exposure provide unique opportunities and challenges to study the association between human behavior and brain function. Acute and chronic alcohol consumption affect a wide range of mood, motor and cognitive measures.2, 73, 74, 75 Alcohol affects neuronal activity,51 but also indirect measures of neuronal activity. Increases in CBF through vasodilation and deceases in glucose metabolism through metabolizing acetate are of examples of effects of alcohol on indirect measures of brain activity.13, 17, 19, 76, 77 Because of the high sensitivity of CBF and CMRglc to non-neuronal alcohol-induced effects, here, we used an alternative index of resting brain activity, that is, resting FCD, to index slow-rate synchronous neuronal rhythms within (lFCD) and between (gFCD) brain regions. Prior research has shown that FCD accounts for a large proportion of glucose demand of resting brain activity.33, 34 Furthermore, there is evidence that resting-state connectivity is more sensitive to the effects of alcohol intoxication on neuronal activity relative to CBF measures.26, 78 Our results show that neither acute nor chronic alcohol affect FCD indices in the whole brain (Supplementary Table 4). This is in contrast to CMRglc11, 13 and CBF6, 79, 80, 81 findings that show significant brain-wide changes with acute alcohol and in alcoholics. Our results support the position that FCD indices are not primarily affected by alcohol-induced vasodilation nor by alterations in energy substrates of brain metabolism.

Overall, alcohol reduced the association between individual differences in ROI FCDs in both groups (P=0.03). It also reduced the neurocognitive coupling between behavior and ROI FCDs in both groups (P<0.0001), but more so in HD (P=0.02). Similar effects were found when using a priori ROIs (Supplementary Figure 3). This indicates that aspects of changes in brain connectivity (indexing brain activity) due to alcohol exposure may be mediated by alcohol’s effect on the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters,51, 52 and in part reflect the brain’s effort (regional reductions or increases in activity) to restore this balance independently from the function of the affected regions. Further delineation of this phenomenon will have to await future research.

Future studies will be needed to assess the reproducibility of our current findings. Particularly, on the basis of our limited sample size, we cannot make strong inferences about the significance of the associations between FCD indices and behavioral measures. Nonetheless, our findings show the promise of resting-state metrics as biomarkers of alcohol-related behavioral changes. Another limitation of this study is gender imbalance between the two groups. Though we used a gender covariate, it does not effectively account for gender imbalance (that is, there were no females in HD) in the group contrasts, and only accounts for within-group gender differences (that is, for NM). To alleviate the concern that the group differences might be driven by gender imbalance82, 83 between NM and HD, we performed group comparisons after excluding the female participants from the NM group. We found similar patterns of differences in lFCD (except for the posterior cingulate cluster) and gFCD between the two groups (Supplementary Figures 4 and 5, PFWE<0.05, corrected for cluster size) to when females were included (Figures 1 and 3, PFWE<0.05, corrected for cluster size). These findings support that gender bias did not primarily contribute to group differences in FCD. Though recent research suggest that there is greater between-subject variability than between-gender variability,84 we cannot ascertain the extent to which group differences are affected by gender imbalance. This limits the generalizability of findings in relation to group differences.

In summary, we have shown that FCD indices are sensitive to regional changes due to acute or chronic alcohol effects. We found that the MDN and VLN in the thalamus were highly sensitive to both acute and chronic alcohol effects of alcohol, while calcarine, cerebellum, posterior cingulate, PFC and precuneus were sensitive to chronic effects of alcohol. Alcohol-induced changes in mood in both groups were predicted by changes in thalamic connectivity, whereas changes in motor performance were associated with the cerebellothalamic network (that is, cerebellar FCD in NM and thalamic FCD in HD). A range of ROIs contributed to predicting cognitive performance in HD, who also performed worse on a range of cognitive tasks relative to NM. Findings indicate that lower cortical and thalamic connectivity in HD contribute to decline in cognitive performance, presumably driven by heavy alcohol use. In conclusion, we presented a novel attempt to link neural and behavioral changes mediated by acute and chronic alcohol exposure that may be used as biomarkers of transitioning from light to heavy drinking.

References

Gunzerath L, Faden V, Zakhari S, Warren K . National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism report on moderate drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2004; 28: 829–847.

Oscar-Berman M, Marinkovic K . Alcohol: effects on neurobehavioral functions and the brain. Neuropsychol Rev 2007; 17: 239–257.

Volkow ND, Mullani N, Gould L, Adler SS, Guynn RW, Overall JE et al. Effects of acute alcohol intoxication on cerebral blood flow measured with PET. Psychiatry Res 1988; 24: 201–209.

Ingvar M, Ghatan PH, Wirsen-Meurling A, Risberg J, Von Heijne G, Stone-Elander S et al. Alcohol activates the cerebral reward system in man. J Stud Alcohol 1998; 59: 258–269.

Blaha M, Aaslid R, Douville CM, Correra R, Newell DW . Cerebral blood flow and dynamic cerebral autoregulation during ethanol intoxication and hypercapnia. J Clin Neurosci 2003; 10: 195–198.

Marxen M, Gan G, Schwarz D, Mennigen E, Pilhatsch M, Zimmermann US et al. Acute effects of alcohol on brain perfusion monitored with arterial spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging in young adults. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014; 34: 472–479.

Sano M, Wendt PE, Wirsen A, Stenberg G, Risberg J, Ingvar DH . Acute effects of alcohol on regional cerebral blood flow in man. J Stud Alcohol 1993; 54: 369–376.

Mathew RJ, Wilson WH, Tant SR . Determinants of resting regional cerebral blood flow in normal subjects. Biol Psychiatry 1986; 21: 907–914.

Newlin DB, Golden CJ, Quaife M, Graber B . Effect of alcohol ingestion on regional cerebral blood flow. Int J Neurosci 1982; 17: 145–150.

Tolentino NJ, Wierenga CE, Hall S, Tapert SF, Paulus MP, Liu TT et al. Alcohol effects on cerebral blood flow in subjects with low and high responses to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2011; 35: 1034–1040.

Volkow ND, Hitzemann R, Wolf AP, Logan J, Fowler JS, Christman D et al. Acute effects of ethanol on regional brain glucose metabolism and transport. Psychiatry Res 1990; 35: 39–48.

Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Franceschi D, Fowler JS, Thanos PP, Maynard L et al. Low doses of alcohol substantially decrease glucose metabolism in the human brain. NeuroImage 2006; 29: 295–301.

Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Shokri Kojori E, Fowler JS, Benveniste H, Tomasi D . Alcohol decreases baseline brain glucose metabolism more in heavy drinkers than controls but has no effect on stimulation-induced metabolic increases. J Neurosci 2015; 35: 3248–3255.

Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Franceschi D, Fowler JS, Thanos PK, Scherbaum N et al. Regional brain metabolism during alcohol intoxication. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000; 24: 822–829.

Kawano Y . Physio-pathological effects of alcohol on the cardiovascular system: its role in hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Hypertens Res 2010; 33: 181–191.

Luchtmann M, Jachau K, Tempelmann C, Bernarding J . Alcohol induced region-dependent alterations of hemodynamic response: implications for the statistical interpretation of pharmacological fMRI studies. Exp Brain Res 2010; 204: 1–10.

Volkow ND, Kim SW, Wang GJ, Alexoff D, Logan J, Muench L et al. Acute alcohol intoxication decreases glucose metabolism but increases acetate uptake in the human brain. NeuroImage 2013; 64: 277–283.

Brand A, Richter-Landsberg C, Leibfritz D . Metabolism of acetate in rat brain neurons, astrocytes and cocultures: metabolic interactions between neurons and glia cells, monitored by NMR spectroscopy. Cell Mol Biol 1997; 43: 645–657.

Lotfi J, Meyer JS . Cerebral hemodynamic and metabolic effects of chronic alcoholism. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev 1989; 1: 2–25.

Nicolas JM, Catafau AM, Estruch R, Lomena FJ, Salamero M, Herranz R et al. Regional cerebral blood flow-SPECT in chronic alcoholism: relation to neuropsychological testing. J Nucl Med 1993; 34: 1452–1459.

Wang J, Du H, Jiang L, Ma X, de Graaf RA, Behar KL et al. Oxidation of ethanol in the rat brain and effects associated with chronic ethanol exposure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 14444–14449.

Jiang L, Gulanski BI, De Feyter HM, Weinzimer SA, Pittman B, Guidone E et al. Increased brain uptake and oxidation of acetate in heavy drinkers. J Clin Invest 2013; 123: 1605–1614.

Gusnard DA, Raichle ME, Raichle ME . Searching for a baseline: functional imaging and the resting human brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2001; 2: 685–694.

De Luca M, Beckmann CF, De Stefano N, Matthews PM, Smith SM . fMRI resting state networks define distinct modes of long-distance interactions in the human brain. NeuroImage 2006; 29: 1359–1367.

Cordes D, Haughton VM, Arfanakis K, Carew JD, Turski PA, Moritz CH et al. Frequencies contributing to functional connectivity in the cerebral cortex in “resting-state" data. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001; 22: 1326–1333.

Du C, Volkow ND, Koretsky AP, Pan Y . Low-frequency calcium oscillations accompany deoxyhemoglobin oscillations in rat somatosensory cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: E4677–E4686.

Khalili-Mahani N, Zoethout RM, Beckmann CF, Baerends E, de Kam ML, Soeter RP et al. Effects of morphine and alcohol on functional brain connectivity during "resting state": a placebo-controlled crossover study in healthy young men. Hum Brain Mapp 2012; 33: 1003–1018.

Weber AM, Soreni N, Noseworthy MD . A preliminary study on the effects of acute ethanol ingestion on default mode network and temporal fractal properties of the brain. MAGMA 2014; 27: 291–301.

Thayer RE, Montanaro E, Weiland BJ, Callahan TJ, Bryan AD . Exploring the relationship of functional network connectivity to latent trajectories of alcohol use and risky sex. Curr HIV Res 2014; 12: 293–300.

Muller-Oehring EM, Jung YC, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV, Schulte T . The resting brain of alcoholics. Cereb Cortex 2014; 25: 4155–4168.

Zhu X, Cortes CR, Mathur K, Tomasi D, Momenan R . Model-free functional connectivity and impulsivity correlates of alcohol dependence: a resting-state study. Addict Biol e-pub ahead of print 3 June 2015.

Tomasi D, Volkow ND . Functional connectivity density mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 9885–9890.

Tomasi D, Wang GJ, Volkow ND . Energetic cost of brain functional connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 13642–13647.

Sengupta B, Stemmler M, Laughlin SB, Niven JE . Action potential energy efficiency varies among neuron types in vertebrates and invertebrates. PLoS Comput Biol 2010; 6: e1000840.

Harris GJ, Oscar‐Berman M, Gansler A, Streeter C, Lewis RF, Ahmed I et al. Hypoperfusion of the cerebellum and aging effects on cerebral cortex blood flow in abstinent alcoholics: a SPECT study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1999; 23: 1219–1227.

Qin L, Crews FT . Focal thalamic degeneration from ethanol and thiamine deficiency is associated with neuroimmune gene induction, microglial activation, and lack of monocarboxylic acid transporters. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2014; 38: 657–671.

Abernathy K, Chandler LJ, Woodward JJ . Alcohol and the prefrontal cortex. Int Rev Neurobiol 2010; 91: 289–320.

Oscar-Berman M, Marinkovic K . Alcoholism and the brain: an overview. Alcohol Res Health 2003; 27: 125.

Kong L, Zheng W, Lian G, Zhang H . Acute effects of alcohol on the human brain: diffusion tensor imaging study. Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 928–934.

Montgomery C, Ashmore KV, Jansari A . The effects of a modest dose of alcohol on executive functioning and prospective memory. Hum Psychopharmacol 2011; 26: 208–215.

Gilman JM, Ramchandani VA, Davis MB, Bjork JM, Hommer DW . Why we like to drink: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study of the rewarding and anxiolytic effects of alcohol. J Neurosci 2008; 28: 4583–4591.

Tomasi D, Wang R, Telang F, Boronikolas V, Jayne M, Wang G-J et al. Impairment of attentional networks after 1 night of sleep deprivation. Cereb Cortex 2009; 19: 233–240.

Volkow ND, Wang G-J, Hitzemann R, Fowler JS, Pappas N, Lowrimore P et al. Depression of thalamic metabolism by lorazepam is associated with sleepiness. Neuropsychopharmacology 1995; 12: 123–132.

Zhu W, Volkow ND, Ma Y, Fowler JS, Wang G-J . Relationship between ethanol-induced changes in brain regional metabolism and its motor, behavioural and cognitive effects. Alcohol Alcohol 2004; 39: 53–58.

Sullivan E, Rosenbloom M, Pfefferbaum A . Pattern of motor and cognitive deficits in detoxified alcoholic men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000; 24: 611–621.

Stavro K, Pelletier J, Potvin S . Widespread and sustained cognitive deficits in alcoholism: a meta‐analysis. Addict Biol 2013; 18: 203–213.

Fein G, Di Sclafani V . Cerebral reserve capacity: implications for alcohol and drug abuse. Alcohol 2004; 32: 63–67.

Noël X, Paternot J, Van der Linden M, Sferrazza R, Verhas M, Hanak C et al. Correlation between inhibition, working memory and delimited frontal area blood flow measured by 99MTC–bicisate spect in alcohol–dependent patients. Alcohol Alcohol 2001; 36: 556–563.

Spadone S, Della Penna S, Sestieri C, Betti V, Tosoni A, Perrucci MG et al. Dynamic reorganization of human resting-state networks during visuospatial attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112: 8112–8117.

Fitzpatrick LE, Crowe SF . Cognitive and emotional deficits in chronic alcoholics: a role for the cerebellum? Cerebellum 2013; 12: 520–533.

Valenzuela CF . Alcohol and neurotransmitter interactions. Alcohol Health Res World 1997; 21: 144–148.

Chastain G . Alcohol, neurotransmitter systems, and behavior. J Gen Psychol 2006; 133: 329–335.

Begleiter H, Kissin B . The Pharmacology of Alcohol and Alcohol Dependence. Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996.

Lloyd B, Burrin J, Smythe P, Alberti KG . Enzymic fluorometric continuous-flow assays for blood glucose, lactate, pyruvate, alanine, glycerol, and 3-hydroxybutyrate. Clinical chemistry 1978; 24: 1724–1729.

Hersen M . Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment, Intellectual and Neuropsychological Assessment. Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004.

Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Poline JB, Grasby PJ, Williams SC, Frackowiak RS et al. Analysis of fMRI time-series revisited. NeuroImage 1995; 2: 45–53.

Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE . Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. NeuroImage 2012; 59: 2142–2154.

Rubinov M, Sporns O . Complex network measures of brain connectivity: uses and interpretations. NeuroImage 2010; 52: 1059–1069.

van den Heuvel MP, Stam CJ, Boersma M, Hulshoff Pol HE . Small-world and scale-free organization of voxel-based resting-state functional connectivity in the human brain. NeuroImage 2008; 43: 528–539.

Tomasi D, Volkow ND . Functional connectivity hubs in the human brain. NeuroImage 2011; 57: 908–917.

de Jong S . SIMPLS: An alternative approach to partial least squares regression. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 1993; 18: 251–263.

Abdi H . Partial least square regression (PLS regression). In: Encyclopedia for Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp 792–795.

McFarland NR, Haber SN . Convergent inputs from thalamic motor nuclei and frontal cortical areas to the dorsal striatum in the primate. J Neurosci 2000; 20: 3798–3813.

Alelu-Paz R, Gimenez-Amaya JM . The mediodorsal thalamic nucleus and schizophrenia. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2008; 33: 489–498.

Chudasama Y, Muir JL . Visual attention in the rat: a role for the prelimbic cortex and thalamic nuclei? Behav Neurosci 2001; 115: 417–428.

Li Z, Xu Y, Warner D, Volkow ND . Alcohol ADME in primates studied with positron emission tomography. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: 10.

Garcia-Cabezas MA, Martinez-Sanchez P, Sanchez-Gonzalez MA, Garzon M, Cavada C . Dopamine innervation in the thalamus: monkey versus rat. Cereb Cortex 2009; 19: 424–434.

Melchitzky DS, Erickson SL, Lewis DA . Dopamine innervation of the monkey mediodorsal thalamus: Location of projection neurons and ultrastructural characteristics of axon terminals. Neuroscience 2006; 143: 1021–1030.

Volkow ND, Tomasi D, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J et al. Predominance of D2 receptors in mediating dopamine’s effects in brain metabolism: effects of alcoholism. J Neurosci 2013; 33: 4527–4535.

Abeliovich A, Hammond R . Midbrain dopamine neuron differentiation: factors and fates. Dev Biol 2007; 304: 447–454.

Okamoto T, Harnett MT, Morikawa H . Hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) is an ethanol target in midbrain dopamine neurons of mice. J Neurophysiol 2006; 95: 619–626.

Baker KG, Harding AJ, Halliday GM, Kril JJ, Harper CG . Neuronal loss in functional zones of the cerebellum of chronic alcoholics with and without Wernicke's encephalopathy. Neuroscience 1999; 91: 429–438.

Steele CM, Southwick L . Alcohol and social behavior I: The psychology of drunken excess. J Pers Soc Psychol 1985; 48: 18–34.

Fillmore MT, Vogel-Sprott M . Response inhibition under alcohol: effects of cognitive and motivational conflict. J Stud Alcohol 2000; 61: 239–246.

Brumback T, Cao D, King A . Effects of alcohol on psychomotor performance and perceived impairment in heavy binge social drinkers. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007; 91: 10–17.

Bjork JM, Gilman JM . The effects of acute alcohol administration on the human brain: insights from neuroimaging. Neuropharmacology 2014; 84: 101–110.

Volkow ND, Hitzemann R, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Burr G, Pascani K et al. Decreased brain metabolism in neurologically intact healthy alcoholics. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149: 1016–1022.

Khalili-Mahani N, van Osch MJ, de Rooij M, Beckmann CF, van Buchem MA, Dahan A et al. Spatial heterogeneity of the relation between resting-state connectivity and blood flow: an important consideration for pharmacological studies. Hum Brain Mapp 2014; 35: 929–942.

Gundersen H, van Wageningen H, Gruner R . Alcohol-induced changes in cerebral blood flow and cerebral blood volume in social drinkers. Alcohol Alcohol 2013; 48: 160–165.

Christie IC, Price J, Edwards L, Muldoon M, Meltzer CC, Jennings JR . Alcohol consumption and cerebral blood flow among older adults. Alcohol 2008; 42: 269–275.

Hata T, Meyer JS, Tanahashi N, Ishikawa Y, Imai A, Shinohara T et al. Three-dimensional mapping of local cerebral perfusion in alcoholic encephalopathy with and without Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1987; 7: 35–44.

Cahill L . Fundamental sex difference in human brain architecture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 577–578.

Tomasi D, Volkow ND . Gender differences in brain functional connectivity density. Hum Brain Mapp 2012; 33: 849–860.

Joel D, Berman Z, Tavor I, Wexler N, Gaber O, Stein Y et al. Sex beyond the genitalia: The human brain mosaic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112: 15468–15473.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ruiliang Wang for MRI data collection and Chris Wong for help and support with data management. This study was supported by NIH/NIAAA intramural research program (Y1AA3009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Molecular Psychiatry website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Shokri-Kojori, E., Tomasi, D., Wiers, C. et al. Alcohol affects brain functional connectivity and its coupling with behavior: greater effects in male heavy drinkers. Mol Psychiatry 22, 1185–1195 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.25

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.25

This article is cited by

-

Patterns of functional connectivity alterations induced by alcohol reflect somatostatin interneuron expression in the human cerebral cortex

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

An integrated multimodal model of alcohol use disorder generated by data-driven causal discovery analysis

Communications Biology (2021)

-

Common and distinct brain functional alterations in pharmacotherapy treatment-naïve female borderline personality disorder patients with and without auditory verbal hallucinations: a pilot study

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (2021)

-

Association of relative brain age with tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, and genetic variants

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Alcohol-responsive genes identified in human iPSC-derived neural cultures

Translational Psychiatry (2019)