Abstract

Many prostate lesions have 'large gland' morphology with gland size similar to or larger than benign glands, complex glandular architecture including papillary, cribriform, and solid, and significant cytological atypia in glandular epithelium with nucleomegaly, prominent nucleoli, or anisonucleosis. The most common and clinically important lesions with 'large gland' morphology include high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN), PIN-like carcinoma, ductal adenocarcinoma, and intraductal carcinoma. These lesions have diverse clinical significance and management implications. HGPIN refers to proliferation of glandular epithelium that displays severe cytological atypia within the confines of prostatic ducts and acini. A HGPIN diagnosis in biopsies connotes ~25% risk of detection of cancer in repeat biopsies. It has been accepted as the main precursor lesion to invasive carcinoma. PIN-like carcinoma is a variant of acinar carcinoma that is morphologically reminiscent of HGPIN and is composed of large cancer glands lined with pseudostratified epithelium. Its clinical outcome is similar to that of usual acinar carcinomas and is graded as Gleason score 3+3=6. Ductal adenocarcinoma comprises large glands lined with tall columnar and pseudostratified epithelium. It is more aggressive than acinar carcinomas and is associated with higher stage disease and greater risk of PSA recurrence and mortality. Intraductal carcinoma is an intraglandular/ductal neoplastic proliferation of glandular epithelial cells that results in marked expansion of glandular architecture and nuclear atypia that often exceeds that in invasive carcinomas. In majority of cases, it is thought to represent retrograde extension of invasive carcinoma into pre-existing ducts and acini. Rarely it may represent a peculiar form of carcinoma with predilection for intraductal location. It is considered an adverse pathological feature and is seen almost always in high-grade and volume carcinoma and harbingers worse clinical outcomes. This article reviews 'new' information on the clinical and pathological features of HGPIN, PIN-like carcinoma, ductal carcinoma, and intraductal carcinoma, and focuses morphological features that aid the differential diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

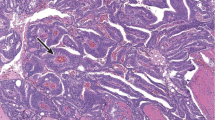

Prostate carcinoma typically has 'small gland' morphology.1 Compared with benign glands, cancer glands with 'small gland' morphology are smaller and have rigid round lumens, and often have characteristic infiltrative growth (Figure 1a). Not infrequently, prostate cancer has 'large gland' morphology with cancer glands appearing as large crowded glands with irregular contour, papillary inholding, and luminal undulation (Figure 1b). They resemble adjacent benign glands architecturally, but are often larger than the latter, and are lined with cytologically atypical cells with nucleomegaly and prominent nucleoli (Figure 1c). Other prostate lesions may also have 'large gland' morphology. The most common and clinically important lesions with 'large gland' morphology include high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) and several histological variants of prostate cancer including PIN-like carcinoma and ductal adenocarcinoma, and intraductal carcinoma. It is crucial to identify correctly these lesions as they have very different clinical significance and management implications (Table 1).

Prostate carcinoma with ‘small gland’ morphology has rigid round lumens, and infiltrates between benign glands (a). In contrast, prostate cancer with 'large gland' morphology presents as crowded large glands with irregular contour, papillary inholding, and luminal undulation (b), and cancer glands are lined with cytologically atypical cells with enlarged nuclei and prominent nucleoli (c).

This article reviews the 'new' information on the clinical and pathological features of HGPIN, PIN-like carcinoma, ductal carcinoma, and intraductal carcinoma, and focuses on the morphological features that aid the differential diagnosis.

High-Grade Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia

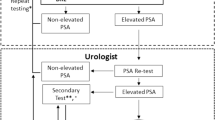

HGPIN refers to proliferation of prostate glandular epithelial cells that display significant cytological atypia within the confines of prostatic ducts and acini.2 It has been accepted as the main precursor lesion to invasive prostate carcinoma.3, 4 It is diagnosed in ~5% of prostate needle biopsies and in almost all radical prostatectomy specimens.5 The incidence and extent increase with age. There is considerable variation in different ethnic background with greater prevalence and extent in blacks compared with Caucasians. HGPIN alone does not result in abnormal digital rectal examination nor elevated serum PSA. It may appear as a hypoechoic lesion on sonography, indistinguishable from prostate carcinoma. The clinical importance of a HGPIN diagnosis in prostate biopsies is the risk of cancer detection in subsequent biopsies.5 HGPIN in needle biopsy denotes ~25% risk of finding prostate carcinoma in subsequent rebiopsy. Ninety percent of cancers diagnosed following HGPIN diagnosis is detected in first or second repeat biopsies. The extent of HGPIN is a strong predictor of cancer in subsequent biopsies.6 When HGPIN involves >1 biopsy cores or sites, National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines for Prostate Cancer Early Detection recommends extended-pattern rebiopsy within 6 months with increased sampling of the affected site and adjacent areas.7 If HGPIN involves only one core, the decision for rebiopsy is based on risk assessment using clinical, radiological, and laboratory findings. No therapy is needed for HGPIN as an isolated finding in needle biopsy.

Diagnosis of HGPIN relies on the histological examination of prostate tissue. Microscopically, HGPIN glands appear at low scanning magnification as dark amphophilic glands that architecturally resemble adjacent benign glands (Figure 2a). At high magnification, luminal cells have amphophilic cytoplasm, nuclear crowding and stratification, irregular spacing and chromatin hyperchromasia, and clumping, and prominent nucleoli visible at × 200 (Figure 2b). If no prominent nucleoli are visible at × 200 magnification, the lesion may represent low-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (LGPIN). However, LGPIN should not be diagnosed owing to poor diagnostic reproducibility and lack of association with increased risk of cancer detection in repeat biopsies. There are four main architectural patterns: flat, tufting, micropapillary, and cribriform.2, 8, 9 Other histological variants, including signet-ring, mucinous, inverted, and small-cell neuroendocrine, are rarely encountered.2, 9 These morphological variations have no clinical significance and are mentioned for the purpose of differential diagnosis. Basal cells in HGPIN are often focal and discontinuous (Figure 3c). AMACR expression is often enhanced compared with adjacent benign glands.

High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) appears at low scanning magnification as dark amphophilic glands that architecturally resemble adjacent benign glands (a, arrow). At high magnification, luminal cells have amphophilic cytoplasm, nuclear crowding and stratification, irregular spacing and chromatin hyperchromasia and clumping, and prominent nucleoli visible at × 200 magnification (b). Basal cells in HGPIN are often focal and discontinuous (c). AMACR expression is often enhanced compared with adjacent benign glands (c). AMACR, alpha-methylacyl-coA racemase.

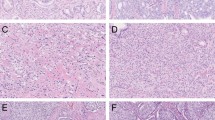

Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia-like (PIN-like) carcinoma appears as a focus of crowded large glands (a). Each individual cancer gland is large and has irregular contour with undulating lumens similar to high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) glands. However, the cancer glands are more crowded than HGPIN. Some cancer glands are confluent with scant intervening stroma. Cancer glands may be markedly dilated (b). In PIN-like carcinoma, cancer glands are lined with pseudostratified cells. The nuclei are round (c). Some tumors show less prominent nucleoli than HGPIN (d). Cancer glands are entirely devoid of basal cells and are positive for AMACR (e). AMACR, alpha-methylacyl-coA racemase.

For differential diagnosis, one should consider a wide range of benign and malignant lesions that have 'large gland' pattern. Benign lesions, including prostatic central zone glands, seminal vesicle/ejaculatory duct epithelium, reactive atypia due to inflammation, infarction or radiation, metaplasia (transitional cell, squamous cell), and hyperplasia (clear-cell cribriform hyperplasia, basal cell hyperplasia), may resemble HGPIN architecturally, but lack significant cytological atypia seen in HGPIN. Malignant lesions with 'large gland' pattern include PIN-like carcinoma, ductal adenocarcinoma, and intraductal carcinoma, and their differential diagnosis are discussed in the following sections.

PIN-like Prostate Carcinoma

Also known as prostate carcinoma with stratified epithelium, PIN-like carcinoma is a variant of acinar carcinoma that is morphologically characterized by large cancer glands lined with pseudostratified epithelium reminiscent of HGPIN.2

PIN-like carcinoma is rare. Hameed and Humphrey10 found its incidence to be 1.3% in prostate biopsies. It is often mixed with, and the clinical presentation is no different from, the usual acinar carcinomas. The clinical behavior of this tumor is not entirely clear. The only study by Tavora and Epstein11 found that the outcomes of these tumors was similar to Gleason score 3+3=6 acinar carcinomas when controlled for stages.11 PIN-like carcinoma is therefore graded as Gleason score 3+3=6.

As its name implies, PIN-like carcinoma resembles HGPIN architecturally. Each individual cancer gland looks like HGPIN with large glands lined with stratified nuclei. However, the glandular crowding in PIN-like carcinoma is in general more pronounced with confluent glands separated by scant intervening stroma in some cases (Figure 3a). Cancer glands are large and typically display tufted and flat patterns (Figure 3a). One common feature seen in PIN-like carcinoma is marked cystic dilatation of cancer glands (Figure 3b) to a degree that only strips of, not intact, glands may be seen in the biopsy, and thus may create diagnostic difficulty when strips of cancer glands are seen at the edge of the biopsy cores. True papillae with fibrovascular cores, cribriform, and solid architecture are, however, not compatible with a PIN-like carcinoma diagnosis, and when present, should suggest a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma (see below).

PIN-like carcinoma glands are lined with pseudostratified cells. The nuclei are either round (Figure 3c) or elongated (Figure 3d). PIN-like carcinoma usually shows less prominent nucleoli than HGPIN. When cancer glands are lined with stratified elongated nuclei, they are also referred to as PIN-like ductal adenocarcinoma by some authorities.11 However, this author prefers 'PIN-like carcinoma' over 'PIN-like ductal adenocarcinoma' as 'ductal adenocarcinoma' connotes a more aggressive behavior comparable to Gleason score 8 cancer (see 'ductal adenocarcinoma’ below), while PIN-like carcinoma is more akin to Gleason score 6 acinar carcinoma and is graded as 3+3=6.

PIN-like carcinoma is by definition entirely devoid of basal cells (Figure 3e). This feature distinguishes PIN-like carcinoma from HGPIN and ductal carcinoma, both of which often display at least focal basal cells. Immunostains for basal cells are in fact required to make a diagnosis of PIN-like carcinoma in virtually all biopsies. AMACR is positive in majority of cancer glands (Figure 3e).

For differential diagnosis, PIN-like carcinoma should be distinguished from HGPIN and ductal adenocarcinoma. PIN-like carcinoma glands are more crowded than HGPIN and are completely devoid of basal cells. Nuclear atypia is typically less pronounced than in HGPIN. In contrast, basal cells are always present in a group of HGPIN glands even though they can occasionally be absent in one or a few small HGPIN glands. As the rule, the diagnosis of PIN-like carcinoma requires multiple glands negative for basal cell markers. A diagnosis of ductal adenocarcinoma is warranted when true papillary, cribriform, solid architectures, and necrosis are present. In contrast, only flat and tufted patterns are seen in PIN-like carcinoma. Furthermore, ductal adenocarcinoma may show patchy basal cell staining as opposed to complete absence in PIN-like carcinoma.

Ductal Adenocarcinoma

Ductal adenocarcinoma is a histologic subtype of prostate carcinoma with large glands lined with tall columnar pseudostratified epithelium.2 Pure ductal adenocarcinoma is rare and accounts for 1.3% of prostate carcinomas. It is typically associated with acinar carcinomas and is reported in 2.6–6.3% cases.12, 13, 14 It affects patients of the same age as acinar carcinomas. Ductal adenocarcinoma is considered a more aggressive disease than acinar carcinomas and is associated with higher stage and greater risk of PSA recurrence and mortality. Percentage of the ductal component is a significant predictor of PSA recurrence.13

To diagnose ductal adenocarcinoma, one must see large cancer glands lined with tall columnar epithelium with stratified nuclei. Several architectural patterns may be seen, including glandular (Figure 3a) (see PIN-like carcinoma above), papillary (Figure 4a), cribriform (Figure 4b), and solid (Figure 4b). These patterns are often admixed together (Figure 4b). Different from acinar carcinoma, ductal adenocarcinoma often elicits remarkable stromal desmoplastic reaction with hemorrhage, edema, and inflammation (Figure 4c). Intraductal spread or partial involvement of benign glands can be seen (Figure 4d). Papillary architecture with true fibrovascular cores is the most useful diagnostic feature (Figure 4a).15 Cribriform glands with elongated nuclei forming rigid punched-out or slit-like lumens (Figure 4b) are also diagnostic, but often are admixed with necrosis or solid areas (Figure 4b). Nuclei in solid area are often not columnar-shaped (Figure 4b). Solid architecture is not specific and must be seen together with other patterns such as papillary and cribriform patterns to make a diagnosis of ductal adenocarcinoma. Nuclear atypia ranges from minimal without prominent nucleoli (Figure 4e) to significant with anisonucleosis, prominent nucleoli, and brisk mitosis, and apoptosis (Figure 4f). Ductal adenocarcinoma is graded as Gleason grade 4 or 5 when solid component or necrosis is present.

In ductal adenocarcinoma, several architectural patterns may be seen, including papillary with true fibrovascular cores (a), cribriform (b), and solid (b). These patterns are often admixed together (b). Ductal adenocarcinoma often elicits remarkable stromal desmoplastic reaction with hemorrhagic and inflammation (c). Intraductal spread or partial involvement of a benign gland can be seen (d). In columnar-shaped tumor cells, nuclear atypia ranges from minimal without prominent nucleoli (e) to significant with nucleomegaly and prominent nucleoli (f).

The immunostaining pattern of ductal adenocarcinoma is similar to that of acinar carcinoma. However, basal cell markers are positive in a basal cell distribution, usually patchy, in ~30% of cases, as the result of intraductal spread. Several studies found a difference between ductal and acinar carcinomas in the expression of such genes as p16, p53, and Ki67.16 PTEN loss and ERG gene fusion are less common in ductal adenocarcinoma than in usual acinar carcinoma.17, 18 A recent study showed that the rate of genomic alteration is comparable between ductal adenocarcinoma and acinar carcinoma of high Gleason score, and ductal adenocarcinoma harbors somatic changes seen in advanced and/or metastatic castration-resistant acinar carcinoma.19

Majority of ductal adenocarcinoma is found in peripheral zone invariably in association with acinar carcinoma and represents advanced stage acinar carcinoma recapitulating ductal morphology or spreading into pre-existing prostate ducts and acini. Infrequently ductal adenocarcinoma arises de novo within the large periurethral ducts in or around the verumontanum, and presents as a small periurethral tumor with no concomitant acinar carcinoma20 (Figure 5). These central-type ductal adenocarcinomas are found to have excellent prognosis as they may represent 'adenocarcinoma in situ' or early phase of ductal adenocarcinoma that arises within the large central periurethral ducts. It may be eradicated by the initial transurethral biopsy or resection alone.21 It is recommended that patients with a diagnosis of ductal adenocarcinoma on transurethral biopsy or resection undergo follow-up transurethral resection and biopsy of the rest of the prostate gland by systemic sextant biopsy before radical surgery is considered.21

For differential diagnosis, it is important to distinguish ductal adenocarcinoma from HGPIN and PIN-like carcinoma. Compared with HGPIN, ductal adenocarcinoma glands are more crowded and extensive and display expansile morphology with true papillae, cribriform, solid architecture, and necrosis. Stromal reaction including hemorrhage and desmoplastic reaction, and evidence of invasion such as perineural invasion and extraprostatic extension, are seen in ductal adenocarcinoma, but not in HGPIN. Ductal adenocarcinoma may have patchy basal cells. Majority of cases, however, lack basal cells. The distinction between ductal adenocarcinoma and PIN-like carcinoma was discussed in the preceding section.

Colorectal adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma may be mistaken for prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma when secondarily involving the prostate. Immunohistochemistry plays a key role in the differential diagnosis. Ductal adenocarcinoma is positive for prostate markers such as prostate-specific antigen and NKX3.1, but negative for gastrointestinal markers such as CDX-2 and markers that are positive in urothelial carcinoma including GATA3, P63, and high-molecular-weight cytokeratins.

Central-type ductal adenocarcinoma arising in the large periurethral glands should be distinguished from prostatic-type urethral polyp, which arises in the prostatic urethra and comprises of crowded benign prostate glands with overlying benign urothelium or prostate glands. Nuclear atypia is absent and basal cells are always present in prostatic-type urethral polyp.

Intraductal Carcinoma of the Prostate

Intraductal carcinoma is an intraglandular/ductal neoplastic proliferation of prostatic glandular epithelial cells that is characterized by marked expansion of glandular architecture and nuclear atypia that often exceeds that in invasive carcinoma.2 It has been long recognized that some 'invasive' prostatic carcinomas had residual basal cells on H&E staining or basal cell immunostains. McNeal and Yemoto22 first reported that it represented an aggressive form of acinar carcinomas, as it was almost always seen in association with invasive carcinoma of high grade and large volume. These high-grade prostate carcinomas with residual basal cells were termed 'intraductal carcinoma'. The concept of 'intraductal carcinoma' has evolved significantly since then to culminate in recognizing intraductal carcinoma as a distinct entity in the 2016 WHO blue book.

Two morphological hallmarks of intraductal carcinoma are expansile growth of atypical cells that forms large dense cribriform and/or solid architecture (Figures 6a and b) and intraductal/acinar location of the atypical cells with preservation of basal cells (Figure 6c). Architecturally intraductal carcinoma can exhibit a plethora of patterns, including loose cribriform (Figure 7a), dense cribriform (Figure 7b), solid (Figure 7c), and comedonecrosis (Figure 7d), representing progressively increasing proliferation of cancer cells. It is not uncommon that intraductal carcinoma partially involves benign glands (Figure 7e). Cytologically, neoplastic cells may exhibit marked variation in nuclear sizes (Figure 7f) and pleomorphic nuclei that are ≥6 × of the adjacent nuclei (Figure 7g). Although characteristic, these nuclear features are not seen in all cases.

A wide range of morphological patterns may be seen in intraductal carcinoma, including loose cribriform (a), dense cribriform (b), solid (c), and glands with comedonecrosis (d). It is not uncommon that intraductal carcinoma partially involves benign glands (e). Cytologically, neoplastic cells exhibit marked variation in nuclear sizes (f) and pleomorphic nuclei that are ≥6 × of the adjacent nuclei (g).

Several diagnostic criteria have been proposed using both histological and molecular markers,23, 24, 25, 26 but the one proposed by Guo and Epstein24 widely used. In addition to the presence of malignant epithelial cells expanding large acini and prostatic ducts with preservation of basal cells, the diagnosis of IDC-P required the presence of solid or dense cribriform pattern (Figures 7b and c). If these features are not present, the diagnosis can be made if there is non-focal comedonecrosis involving >2 glands (Figure 7d); or marked nuclear atypia where the nuclei are at least six times larger than adjacent benign nuclei (Figure 7e).

Many genetic changes have been reported in intraductal carcinoma. So far, evidence suggests that intraductal carcinoma is distinct from HGPIN and represents a late-stage event in prostate cancer progression. Several studies have shown that ERG gene fusion in 58–75% of intraductal carcinomas and the ERG gene status was 100% concordant between intraductal carcinoma and adjacent invasive carcinoma.27 Loss of cytoplasmic PTEN protein was found in 84% of intraductal carcinomas and such a loss was concordant between intraductal carcinoma and adjacent acinar carcinoma in 92% of cases.28 Therefore, ERG and PTEN status may help distinguish intraductal carcinoma from its mimickers including HGPIN.

Intraductal carcinoma is associated with adverse findings in radical prostatectomies, including high Gleason score, large tumor volume, high pathologic stage, and is a predictor of clinical outcomes independent of other established clinical and pathological parameters.26, 29 When diagnosed in prostate biopsies, intraductal carcinoma is often associated with high-grade and volume carcinoma. Rarely it is diagnosed in prostate biopsies as an isolated finding without concomitant invasive carcinoma.30, 31 In these rare situations, a comment should be made stating that intraductal carcinoma is almost always associated with high-grade and volume invasive cancer and that definitive treatment may be offered to the patient even in the absence of invasive carcinoma in the biopsy.31 Alternatively, some pathologists would recommend immediate repeat biopsy.

Intraductal carcinoma is not Gleason graded.32 If present concomitantly with a high-grade (Gleason patterns 4 and 5) invasive carcinoma, diagnosis of intraductal carcinoma may be of little significance for patient management purpose. The diagnosis of intraductal carcinoma should be confirmed using basal cell markers when there is concern whether the biopsy contains intraductal carcinoma only or invasive cancer, or when the Gleason grade could change with the diagnosis of intraductal carcinoma.

The above-mentioned histological criteria are highly specific for the diagnosis of intraductal carcinoma; however, they do not encompass the entire morphological spectrum. Significant proportion of intraductal carcinomas may exhibit 'low-grade' features that fall short of Guo and Epstein's criteria (Figure 8) and may mimic HGPIN.25, 27, 28, 29, 30 Such lesions have also been referred to as 'atypical intraductal proliferation'. Accumulating evidence suggests that such lesions indeed represent intraductal carcinoma. Haffner et al33 used TMPRSS2-ERG genomic breakpoints as the markers for clonality and PTEN deletion status as the markers for temporal evolution and found that the low-grade, 'PIN-like' atypical lesions adjacent to invasive acinar carcinomas represent retrograde colonization of benign glands with cancer cells, or 'intraductal carcinoma'. Hickman et al.34 and Shah et al35 found the 'atypical intraductal proliferation' that is histologically worse than HGPIN, but lacks the diagnostic criteria for intraductal carcinoma had genetic alterations (ERG and PTEN status) and clinical behavior similar to the bona fide intraductal carcinoma. A recent study by Morais et al18 found these borderline lesions between HGPIN and intraductal carcinoma, when diagnosed on biopsies, are associated with a substantial increased risk (50%) of invasive carcinoma and/or intraductal carcinoma on repeat biopsy. These findings confirm the initial observation that intraductal carcinoma has a morphological spectrum wider than the classical morphology,27 and 'PIN-like' atypical lesions adjacent to invasive carcinoma may represent ‘low-grade’ intraductal carcinoma. They also raise a very important question as how to manage 'atypical intraductal proliferation' that is morphologically more atypical than HGPIN, but not sufficient for intraductal carcinoma in prostate biopsies. These lesions should not be simply regarded as HGPIN, which may be conservatively followed. On the contrary, immediate repeat biopsy is warranted in this setting to rule out unsampled invasive carcinoma.

Conclusions

Many prostate lesions display atypical 'large gland' pattern with glandular size and contour similar or larger than benign glands and significant cytological atypia in the glandular epithelium. For the purpose of clinical management, four lesions should always be considered, including HGPIN, PIN-like carcinoma, ductal adenocarcinoma, and intraductal carcinoma. For differential diagnosis, one should first evaluate whether the atypical glands are focal or extensive and whether the involved glands display expansile growth such as dense cribriform and solid glands. One should then look for atypical nuclear features, especially anisonucleosis and nucleomegaly. Prudent use of basal cell markers can demonstrate whether basal cells are retained in the atypical glands. Finally, new markers such as PTEN and ERG may be used to distinguish intraductal carcinoma from its mimickers such as HGPIN.

References

Shah RB, Zhou M . Prostate Biopsy Interpretation: An Illustrated Guide. Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, Dordrecht, Netherlands, London, UK, New York, USA, 2012.

Moch H, Humphrey PA, Ulbrigh TM, Reutere VE (eds). WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2016.

De Marzo AM, Haffner MC, Lotan TL et al. Premalignancy in prostate cancer: rethinking what we know. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2016;9:648–656.

De Marzo AM, Platz EA, Sutcliffe S et al. Inflammation in prostate carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 2007;7:256–269.

Epstein JI, Herawi M . Prostate needle biopsies containing prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia or atypical foci suspicious for carcinoma: implications for patient care. J Urol 2006;175 (Part 1):820–834.

Herawi M, Kahane H, Cavallo C et al. Risk of prostate cancer on first re-biopsy within 1 year following a diagnosis of high grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia is related to the number of cores sampled. J Urol 2006;175:121–124.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Guidelines in Oncology: Prostate Cancer Early Detection, 2017. Available at: NCCN.org.

Bostwick DG, Amin MB, Dundore P et al. Architectural patterns of high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Hum Pathol 1993;24:298–310.

Montironi R, Mazzucchelli R, Lopez-Beltran A et al. Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia: its morphological and molecular diagnosis and clinical significance. BJU Int 2011;108:1394–1401.

Hameed O, Humphrey PA . Stratified epithelium in prostatic adenocarcinoma: a mimic of high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Mod Pathol 2006;19:899–906.

Tavora F, Epstein JI . High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasialike ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate: a clinicopathologic study of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:1060–1067.

Dube VE, Farrow GM, Greene LF . Prostatic adenocarcinoma of ductal origin. Cancer 1973;32:402–409.

Jang WS, Shin SJ, Yoon CY et al. Prognostic significance of the proportion of ductal component in ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate. J Urol 2017;197:1048–1053.

Seipel AH, Wiklund F, Wiklund NP et al. Histopathological features of ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate in 1,051 radical prostatectomy specimens. Virchows Arch 2013;462:429–436.

Seipel AH, Delahunt B, Samaratunga H et al. Diagnostic criteria for ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate: interobserver variability among 20 expert uropathologists. Histopathology 2014;65:216–227.

Seipel AH, Samaratunga H, Delahunt B et al. Immunohistochemical profile of ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Virchows Arch 2014;465:559–565.

Lotan TL, Toubaji A, Albadine R et al. TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions are infrequent in prostatic ductal adenocarcinomas. Mod Pathol 2009;22:359–365.

Morais CL, Han JS, Gordetsky J et al. Utility of PTEN and ERG immunostaining for distinguishing high-grade PIN from intraductal carcinoma of the prostate on needle biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:169–178.

Seipel AH, Whitington T, Delahunt B et al. Genetic profile of ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Hum Pathol 2017.

Melicow MM, Tannenbaum M . Endometrial carcinoma of uterus masculinus (prostatic utricle). Report of 6 cases. J Urol 1971;106:892–902.

Aydin H, Zhang J, Samaratunga H et al. Ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate diagnosed on transurethral biopsy or resection is not always indicative of aggressive disease: implications for clinical management. BJU Int 2010;105:476–480.

McNeal JE, Yemoto CE . Spread of adenocarcinoma within prostatic ducts and acini. Morphologic and clinical correlations. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:802–814.

Cohen RJ, Wheeler TM, Bonkhoff H et al. A proposal on the identification, histologic reporting, and implications of intraductal prostatic carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2007;131:1103–1109.

Guo CC, Epstein JI . Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate on needle biopsy: histologic features and clinical significance. Mod Pathol 2006;19:1528–1535.

Shah RB, Magi-Galluzzi C, Han B et al. Atypical cribriform lesions of the prostate: relationship to prostatic carcinoma and implication for diagnosis in prostate biopsies. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:470–477.

Shah RB, Zhou M . Atypical cribriform lesions of the prostate: clinical significance, differential diagnosis and current concept of intraductal carcinoma of the prostate. Adv Anat Pathol 2012;19:270–278.

Han B, Suleman K, Wang L et al. ETS gene aberrations in atypical cribriform lesions of the prostate: Implications for the distinction between intraductal carcinoma of the prostate and cribriform high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:478–485.

Lotan TL, Gumuskaya B, Rahimi H et al. Cytoplasmic PTEN protein loss distinguishes intraductal carcinoma of the prostate from high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Mod Pathol 2013;26:587–603.

Robinson B, Magi-Galluzzi C, Zhou M . Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012;136:418–425.

Watts K, Li J, Magi-Galluzzi C et al. Incidence and clinicopathological characteristics of intraductal carcinoma detected in prostate biopsies: a prospective cohort study. Histopathology 2013;63:574–579.

Robinson BD, Epstein JI . Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate without invasive carcinoma on needle biopsy: emphasis on radical prostatectomy findings. J Urol 2010;184:1328–1333.

Epstein JI, Egevad L, Amin MB et al. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma: Definition of Grading Patterns and Proposal for a New Grading System. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:244–252.

Haffner MC, Weier C, Xu MM et al. Molecular evidence that invasive adenocarcinoma can mimic prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) and intraductal carcinoma through retrograde glandular colonization. J Pathol 2016;238:31–41.

Hickman RA, Yu H, Li J et al. Atypical intraductal cribriform proliferations of the prostate exhibit similar molecular and clinicopathologic characteristics as intraductal carcinoma of the prostate. Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41:550–556.

Shah RB, Yoon J, Liu G, Tian W . Atypical intraductal proliferation and intraductal carcinoma of the prostate on core needle biopsy: a comparative clinicopathological and molecular study with a proposal to expand the morphological spectrum of intraductal carcinoma. Histopathology 2017, doi: 10.1111/his.13273 [e-pub ahead of print 1 June 2017].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, M. High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, PIN-like carcinoma, ductal carcinoma, and intraductal carcinoma of the prostate. Mod Pathol 31 (Suppl 1), 71–79 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.138

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.138

This article is cited by

-

Nomogram for predicting the overall survival and cancer-specific survival of patients with intraductal carcinoma of the prostate

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2024)

-

Prostatic adenocarcinoma with a peculiar morphology – a rare case of pseudohyperplastic variant with inverted polarity

Surgical and Experimental Pathology (2022)

-

Survival after radical prostatectomy vs. radiation therapy in ductal carcinoma of the prostate

International Urology and Nephrology (2022)

-

Optimizing the diagnosis and management of ductal prostate cancer

Nature Reviews Urology (2021)

-

Prostate cancer

Nature Reviews Disease Primers (2021)