Abstract

During most of the nineteenth century, the discipline of pathology in Boston made substantial strides as a result of physicians and surgeons who practiced pathology on a part-time basis. The present essay tells the subsequent story, beginning in 1892, when full-time pathologists begin to staff the medical schools and hospitals of Boston. Three individuals from this era deserve special mention: William T Councilman, Frank Burr Mallory and James Homer Wright, with Councilman remembered primarily as a visionary and teacher, Mallory as a trainer of many pathologists, and Wright as a scientist. Together with S Burt Wolbach in the early-to-mid-twentieth century, these pathologists went on to train the next generation of pathologists—a generation that then populated the various hospitals that were developed in Boston in the early 1900s. This group of seminal pathologists in turn formed the diagnostically strong, academically productive, pathology departments that grew in Boston over the remainder of the twentieth century.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

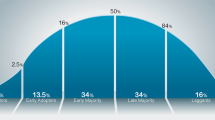

The discipline of pathology in Boston has a rich history, extending from the early 19th century through the present day.1 Up to ~1950, the story can be divided roughly into three eras. The first begins with the founding in 1811 of the first full hospital in Boston, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), and features physicians and surgeons who practiced elements of pathology part-time; these included members of the Warren family as well as notables such as John Barnard Swett Jackson, the first professor of pathology in the United States, and Reginald Heber Fitz, the first person to have the title of ‘pathologist’ in Boston.2 The second era starts in 1892, when William T Councilman was recruited to Harvard Medical School (HMS) from Johns Hopkins University; Councilman in turn recommended the appointments of Frank Burr Mallory at the Boston City Hospital (BCH) and James Homer Wright at the MGH—two pioneering full-time pathologists who, along with Councilman, set the stage for the further development of pathology in the city. The last part begins in the earlier decades of the 20th century and tells the story of Councilman and Mallory’s trainees, including S Burt Wolbach, who went on both to found and inspire the pathology departments of the many hospitals that had grown in Boston over the first half of the twentieth century (Figures 1 and 2).

Gathering of distinguished pathologists (and a few physicians) at the Mallory Institute of Pathology in the late 1940s. Back row, left to right: Drs Maxwell Finland, Shields Warren, unknown, Tracy B Mallory, William B Castle, Sidney Farber, Harold MacMahon, unknown, unknown; Front row, left to right: unknown, Drs G Kenneth Mallory, Timothy Leary, Frederic B Parker, Raymond D Adams, Arthur T Hertig.

The 19th century and the era of physician-pathologists: the Warrens and their colleagues

The first era of pathology extended from 1811 through 1892, and largely reflected the work of individuals who were primarily physicians and surgeons and who secondarily pursued studies in anatomical and clinical pathology, with much of the anatomic pathology directed toward education and research rather than clinical ends. This era featured the two founders of the MGH, the surgeon John Collins Warren (1778–1856), and the physician James Jackson (1777–1867), as well as their relatives over the subsequent decades, particularly John Barnard Swett Jackson (1806–1879) and J Collins Warren (1842–1927). Other notables included the first individuals to introduce and implement microscopy at MGH and HMS, including Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809–1894) and Calvin Ellis (1826–1883), and the first to hold titles of Pathologist, Reginald Heber Fitz (1843–1918), and of Surgical Pathologist, William Fiske Whitney (1850–1921).1

The story of this first era is told in detail elsewhere.2 We concluded our essay on that period with the following comments, under the subtitle The End of the Beginning: 'William T Councilman arrived at HMS to succeed Fitz as Shattuck Professor of Pathological Anatomy in 1892. This augured a new era of pathology in Boston, reflecting the changing times...’ The present essay picks up the story in 1892 and continues it until about 1950.

The turn of the last century and the transition to full-time pathologists: William Councilman, Frank Burr Mallory, and James Homer Wright

The end of the nineteenth century was a critical period for American medicine. Systemic reform was needed if the United States was to participate in the great advances in medical discovery and practice that were occurring in Europe, particularly in Germany.3 Pathology, a specialty that included the microscopic examination of diseased tissues and the new science of bacteriology, was seen as an important agent of medical progress. With an eye to this, HMS recruited, for the first time, a medical school professor who was not home-grown, William T Councilman, from Johns Hopkins (an institution that had pioneered in the establishment of pathology as a critical discipline), as the Shattuck Professor of Pathology (Pathological Anatomy).4 Councilman, in turn, placed two brilliant men in positions within his purview, Frank Burr Mallory at BCH and James Homer Wright at MGH.5 Together, these three men set the future trajectory of pathology in Boston and are often referred to as the founders of the Boston School.

Each of these three exceptional individuals contributed their multifaceted talents to the emergence of Pathology as a modern medical specialty. As described in more detail below, Councilman was pre-eminent as a visionary and teacher,6 Mallory as a leader and ‘trainer of men’7 and Wright as a scientist.8 They were at the vanguard of a new American century of progress in medical science and education; they were influential in the education and formation of the US leadership in pathology going forward to mid-century; they made key contributions to the improvement and standardization of laboratory techniques and pathology practice in the United States and elsewhere; and they advanced Pathology as an academic medical discipline, a clinical specialty and an investigative science.

William Thomas Councilman

Born in Pikesville, Maryland, on 1 January 1854, Councilman (Figure 3) was the son of a country doctor. By his own account he was raised ‘barefoot’, close to nature on the family farm.9 He graduated with an MD degree from the University of Maryland in 1878 and developed an early interest in dissection and microscopic investigation of tissues. He was appointed as a pathologist to the Baltimore Quarantine Station (1878–79) and was awarded a Fellowship in the Johns Hopkins Department of Biology under the direction of HN Martin in 1880. Councilman sought to further his education in pathology and in late 1880 went to Europe, where he spent a year at leading centers, notably Vienna (the Rokitansky School), Leipzig with Cohnheim and Weigert (students of Virchow) and with Chiari in Prague. On his return to Baltimore, he was appointed Pathologist at Bayview Hospital; he taught at the University of Maryland and its College of Physicians and Surgeons and was appointed Associate in Pathology at Johns Hopkins in 1886.

During his years at Hopkins, Councilman worked closely with the leaders of this new institution, already perceived to be a model for American scientific medicine. The faculty included physician William Osler, surgeons William S Halsted and Howard A Kelly, and a cadre of outstanding physicians and scientists who were led by William H Welch, Professor of Pathology and the Dean of the new medical school.3 When approached by Harvard President, Charles Eliot, Welch recommended Councilman for the Shattuck chair.

Councilman had been active in research during his years in Baltimore. He identified the malaria parasite in red blood cells, confirming the earlier (but at the time disputed) work of Leveran.10, 11 His name is eponymously associated with the characteristic apoptotic bodies that he described in the livers of patients with yellow fever (Councilman bodies) (Figure 4).12 Another important contribution (with HA Lafleur) was an original and definitive description of amebic dysentery.13 Among his notable publications during his Boston career was a detailed study of cerebrospinal meningitis (with FB Mallory and JH Wright),14 a study of diphtheria (with FB Mallory),15 an extensive treatise (with GB Magrath and others) on the pathology of smallpox,16, 17 and a valuable pathology teaching manual for students and instructors (Figure 5).

Councilman bodies (a), from ref. 12.

Councilman’s initial clinical appointment in Boston in 1892 was Chief of Pathology at BCH. He placed FB Mallory, who was already at HMS, as an assistant in Pathology. Over time, Mallory played the larger role at the hospital and was appointed Chief in 1908. When the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital was opened in 1913, Councilman became its first Chief of Pathology.

‘His most important work at Harvard University was his influence on teaching,’ according to his successor SB Wolbach.6 Shortly after taking up his new position, Councilman reorganized the teaching program, introduced student laboratories and reduced the emphasis on lectures. He is quoted as saying, ‘I think lecturing is an intellectual stimulus (for the lecturer) and comparatively harmless to the audience.’9 Councilman was a gifted and engaging teacher, who was revered by his students and inspired many future leaders in pathology and medicine.

Shortly after coming to Boston he married Isabella Coolidge, a member of a prominent Boston family. He and his wife and family of three daughters lived at 78 Baystate Road in Boston. They had a summer home in York, Maine, where Councilman pursued his love of gardening. His interests in trees and horticulture also found an outlet at the Arnold Arboretum, where he was said to be as knowledgeable about the plantings as the Director, his friend Charles S Sargent. In addition to these accomplishments, according to Harvey Cushing, he was a deadly shot with a pistol and could swear at a golf ball-like few others!4

In the final years of his career at Harvard, Councilman explored new horizons. He published a lengthy report of medical and anthropological interest of the Rice expedition to the Amazon, on which he served as medical officer.18 Prior to his retirement in 1923, he spent two years as visiting professor of pathology in China at Peking Union College, sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation (Figure 6). Among his last scholarly publications was a study reported in the Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences on the root system of the Mayflower, a tiny aromatic wildflower.19 His activities were constrained in his later years by angina pectoris. He died while working in his garden in York on 26 May 1933.

Frank Burr Mallory

Frank Burr Mallory (Figure 7), the son of a Great Lakes ship’s captain, was born in Cleveland, Ohio on 12 November 1862. He attended Harvard College, supporting himself by waiting on tables in the dining hall, and graduated in 1886.7, 20, 21 He went on to HMS and graduated in 1890. He was appointed Assistant in Histology at HMS, a department in which he had previously worked as a technician. On Councilman’s arrival in Boston, he was appointed as an assistant in Pathology at BCH.

Mallory married Persis McClain Tracy in 1893 and they had two sons, Tracy Burr (1896–1951) and George Kenneth (1900–1986), both destined to lead Boston departments of pathology with distinction (Figure 8). Following their wedding the couple went to Europe, where Mallory spent a year studying with Chiari in Prague and Ziegler in Freiburg. In 1896 he was appointed First Assistant Pathologist at BCH and Assistant Professor at HMS.

1896 also marked the birth of his first son and the opening of the new Pathology laboratory at BCH.22 This impressive building, 180 ft long by 42 ft wide, had two stories over the basement and an attached mortuary and chapel. The post-mortem room, 32 ft by 20 ft was placed within an auditorium extending through two floors and had seating for 70 observers, reflecting the centrality of performance of autopsies to the laboratory’s mission at the time. There was ample accommodation for bacteriological work and laboratory space designated for research, as well as space assigned for a clinical laboratory for use ‘by the medical and surgical interns.’ That the trustees saw fit to make an investment on this scale reflected the new status of Pathology in Boston medicine. In a 1906 report on the department, Mallory notes that the (clinical) work of the laboratory consists of ‘the making of autopsies’ (1934 cases between 1897 and 1904), examination of surgical specimens (~900 per year), and bacteriological study of material from various sources including autopsies (eg, up to 150 throat swabs for diphtheria each day).23

A detailed insight into the work of a pathological department in this era can be gained from examination of the multiple editions of Pathological Technique, A Practical Manual for Workers in Pathological Histology and Bacteriology (Figure 9), written by FB Mallory and his friend at MGH, James Homer Wright (see below).24 This manual has been characterized as the ‘bible’ of laboratory methods of the period; it was first published in 1895 and revised in seven subsequent editions. The manual, with detailed descriptions of methodology and technology, encompassed the scope of the clinical mission of pathology departments of the time. It was organized into three main sections: I, post-mortem examinations; II, bacteriological methods; and III, histological methods. Its first edition had 400 pages and 105 illustrations.

From the outset, Mallory was committed to the training of future generations of pathologists, and described his department as being organized ‘along the lines of a professional training school.’23 Structured training of not more than 3 years was provided under Mallory’s close direction. More than 120 graduates emerged from the program, including many distinguished future leaders in pathology and chiefs at major Boston teaching hospitals (see below): MGH (Tracy B Mallory—his elder son), Peter Bent Brigham Hospital (S Burt Wolbach), New England Deaconess Hospital (Shields Warren), Tufts (Timothy Leary and H Edward MacMahon) and BCH (Frederic Parker, Jr and George K Mallory—his second son).7

Mallory held the position of Chief of Pathology at Boston City from 1908 to his retirement in 1932, and he continued on the staff as a Consultant until his death in 1941. He was promoted to Associate Professor at HMS in 1901. He resigned his Harvard appointment in 1919 as a result of a dispute with the University but they were later reconciled and Mallory was then appointed Professor in 1928 and Professor Emeritus on reaching retirement age in 1932.

There were few areas of research in pathology that did not attract Mallory’s attention. He made notable contributions to histological methods25 using the newly available aniline dyes and developed widely adopted stains for connective tissue, muscle cells, and neuroglia.24, 26 His work included several definitive descriptive studies of the pathology of infectious diseases, typhoid, diphtheria, pertussis, scarlet fever, and measles, studies of nephritis and other work on the classification of tumors.27, 28, 29, 30 His descriptive and experimental investigations of cirrhosis of the liver focused on alcohol-related liver disease, hemochromatosis and the role of copper in liver injury.31 His name is eponymously associated with the hyaline material that accumulates in the hepatocytes in alcoholic liver disease, Mallory’s hyalin (sic) (Figure 10).32 His published work, including his 662-page book ‘The Principles of Pathologic History’27 (Figure 11), was marked by clear and elegant illustrations, whether as camera lucida drawings or photomicrographs. This fastidiousness carried over into his stewardship of the American Journal of Pathology, of which he was editor-in-chief from 1923 to 1940.

Mallory’s Hyaline. Camera lucida image of alcoholic hyaline in FB Mallory’s textbook Priniciples of Pathologic Histology (Elsevier 1914, digitized by Google Books). The original caption for the image read: ‘Alcoholic Cirrhosis. Liver cells containing hyalin, undergoing necrosis and attracting chiefly polymorphonuclear leucocytes.’.

Mallory received many awards during his career including honorary degrees from Boston University and Tufts University, the Kober Medal of the American Association of Physicians, and the Gold-Headed Cane Award of the American Association of Pathologists. The City of Boston in 1933 named a new pathology building at BCH (the Mallory Institute of Pathology) in his honor. Notwithstanding his life-long immersion in his work, he was a strong family man, enjoyed the outdoors and is reported to have been an excellent tennis player. He died, at the age of 78, on 27 September 1941.

James Homer Wright

James Homer Wright (Figure 12) was born on 8 April 1869 in Pittsburgh, PA, USA.8 He attended John Hopkins University, and graduated with honors in 1890. He subsequently attended the medical school of the University of Maryland and graduated in 1892, receiving the gold medal and the first prize in surgery. Following graduation he worked under William H Welch and Councilman at the pathologic laboratory of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. The following year he took an appointment as a Thomas A Scott fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, under the direction of John Shaw Billings, where he conducted an investigation of the bacteriology of the water supply of Philadelphia that was published in 1893 in the Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences. The potential of this young man was clear to Councilman, who recruited him as an assistant in Pathology at the Sears laboratory at BCH in 1893.

Put forward by Councilman, the 27-year-old James Homer Wright was appointed Director of Pathology at the MGH in 1896 and became the head of its newly constructed state-of-the art clinical laboratory and the institution’s first full-time pathologist. Wright continued to collaborate with his friend Frank Burr Mallory at Boston City and, as noted above, the first edition of their co-authored Pathological Technique appeared in 1898.24 The scope of Wright’s clinical service included the performance of autopsies, bacteriological testing on a large scale, and small but increasing numbers of surgical pathology specimens. He had a strong preference for research over clinical work and relied on able assistants for the majority of the clinical activities of the department—notably Oscar Richardson, Albert Steele (bacteriologist), William Whitney (surgical pathologist), and Harry Hartwell (surgical pathologist).8, 33

Wright was a talented researcher and he attracted and mentored many physicians of like mind, not least by affording them bench space in his laboratory. Among such men was George Minot,34 of pernicious anemia fame, who, in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech in Stockholm in 1934, acknowledged his particular debt to Wright. Another collaborator worthy of mention was Elliot Joslin, of diabetes fame (Joslin Clinic), with Wright and Joslin publishing one of the earliest pathological descriptions of islet cell loss in diabetes.35 The scope of Wright’s investigations was broad and included hematology, infectious disease, neoplasia, and laboratory techniques.36 His research made lasting contributions to medicine, not least his simple and elegant reworking of the Leishman-Romanowsky stain, published in the American Journal of Medical Research (later American Journal of Pathology) in 1902,37 which serves to this day as a definitive hematological method and bears his name as the Wright stain. This method was key to his seminal work on the histogenesis of plates (platelets), which was first reported in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (later the New England Journal of Medicine) in 1906.38 Studying the megakaryocytes of multiple species, he was able to show the identity of the staining characteristics of the megakaryocyte cytoplasm and platelets. He was not one to rely entirely on morphology, however, and in his study proffered an additional eight independent proofs.

Prior to the platelet study, Wright’s technical skills were in evidence in a paper published in the Boston Journal of Medical Science in 1900, in which he reported, for the first time, that multiple myeloma represented a malignancy of plasma cells.39 This was supported by a series of high-quality photomicrographs that proclaimed the identity of the tumor cells. Wright gave some credit for the discovery to the quality of the thin sections of the tumor he was able to produce using a new Blake-Minot rotary microtome. A second eponymous association with Wright is the Homer Wright pseudorosettes of neuroblastoma (Figure 13). He first described these in a paper published in 1910,40 in which he noted the ball-like arrangements of small cells with centrally placed fibrils. Based on his knowledge of the embryology of the sympathetic nervous system, he proposed that these represented tumors of undifferentiated neurocytes or neuroblasts rather than ‘sarcomatous’ tumors, as they had been previously characterized. To this day, it remains unclear why Wright’s middle name, Homer, is part of this eponym but not others (eg, the Wright stain).

Wright published numerous studies of infectious disorders related to bacteria, spirochetes, fungi, and parasites. Notable among these was a study of Actinomycosis,41 which led to an invitation to contribute on the subject in the first edition of Osler’s Modern Medicine published in 1907. Another important contribution was an early report on the demonstration of spirochetes with a Levaditi stain in a series of cases of aortitis,42 which was also hailed by Osler in a congratulatory letter to Wright as definitive proof of the nature of syphilitic aortitis.

As observed in an obituary by Councilman, James Homer Wright ‘was not a social man, rarely going to medical meetings, but he formed many enduring friendships.’43 He received multiple awards: two major prizes for his research, the Gross Prize for his study of actinomycosis and the Boylston Prize of Harvard University for his platelet studies; as well as honorary doctorates of science from University of Missouri, Harvard University and University of Maryland; and in 1915 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Shortly after his arrival in Boston he met Norwegian opera singer Aagot Lunde who was giving a recital in the city, He courted her with serial bouquets of roses and they got married on Christmas day 1901. The couple lived happily in Newton, MA, USA, and had a summer home in Duxbury. They made frequent trips to Norway, and Wright was said to have become fluent in Norwegian. Mrs Wright died of cancer in 1923. Wright himself did not thrive in the years following, and he died at MGH on 3 January 1928 of pneumonia, which he contracted returning from a Christmas visit to his family in Pittsburgh.8

The early 20th century and the spread of pathology in Boston: the many hospitals and descendants

The turn of the last century witnessed the emergence of many hospitals in Boston, as in other cities around the United States and the world. Some of these were specialized from the start (eg, Children’s Hospital, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston Psychopathic Hospital), whereas others grew as general hospitals to serve particular groups (Boston/New England Baptist Hospital, Beth Israel Hospital). As the importance of diagnostic laboratory testing grew, so did the need for each hospital to have a dedicated pathologist. The story of pathology in Boston in the first half of the twentieth century is thus one of a dispersion of budding young pathologists trained at places like BCH, Peter Bent Brigham Hospital and MGH who moved to these newer hospitals and established illustrious new departments.

The ‘Descendants’ of Frank Burr Mallory

The trainee-descendants of Frank Burr Mallory were numerous, with his first trainee, Timothy Leary, providing a list in 1933 of over 120 trainees, most of them in the discipline of pathology.7 These individuals populated departments around the country, and most of the older and more recent departments in Boston. At the BCH, itself, Frederic ‘Ted’ Parker, Jr (1890–1969) (Figure 14), who had trained with FB Mallory, followed Mallory as the chief of Pathology, serving in that role from 1932 until 1951. He was a superb diagnostician (with Mallory claiming that Parker was a better diagnostic pathologist than he was!) and was interested in renal disease and hematopathology, including publishing seminal articles on Hodgkin’s lymphoma in the New England Journal of Medicine as well as the so-called Jackson-Parker classification of lymphomas44 (Figure 15). Despite having a good sense of humor, he reportedly had an unusual personality, often not leaving his office. It was said that, ‘He was extremely clever in spite of his neurosis and phobia of most people. He wouldn’t let them in his office, while he sitting at his microscope... full of self-doubts, he’d go away for a few weeks and come back and lock himself up and test himself on slides to make sure he was all right.’45 Nonetheless, he had a powerful influence on patient care and on training. Following Parker as head of Pathology at the BCH (from 1951 to 1966) was the younger of FB Mallory’s two sons who became pathologists, G Kenneth Mallory (1900–1986) (Figure 8b), who is perhaps best remembered as the ‘Mallory’ of Mallory–Weiss tears in the esophagus.46 Both Boston University and Tufts medical schools established clinical and academic affiliations with BCH and the Mallory Institute in 1932. GK Mallory was appointed Professor of Pathology on the Boston University service and in 1946 succeeded Parker (who was a Professor at HMS) as Director of the Mallory Institute. All subsequent directors of the Institute had Boston University academic appointments and served as chairs of Pathology at Boston University School of Medicine. (In 1973, the Harvard and Tufts affiliations with BCH came to an end).

A number of individuals who trained at the BCH went on to illustrious careers at the MGH. One was Tracy Burr Mallory (1896–1951) (Figure 8a), who trained with his father (FB Mallory) and the famous microbiologist at Harvard, Hans Zinsser. Tracy Mallory was the chief of Pathology at the MGH from 1926 to 1951. In this role, he started the MGH pathology residency training program and became the editor of the Clinico-Pathological Conferences of the MGH published in the New England Journal of Medicine, serving in that role from 1935 to 1951. During World War II, Mallory was the Chief Pathologist for Mediterranean theater and he published a number of important papers on the pathology of war injuries and their sequelae.

Other notables who went from BCH to influence pathology at MGH were in the field of neuropathology—a subspecialty that had the largest semi-independent development from the rest of pathology in the first half of the 20th century. The neuropathology laboratory at MGH was started in 1927 by Charles S Kubik (1891–1982) (Figure 16), who had trained with J Godwin Greenfield in London, but the trainees of the BCH rapidly influenced the laboratory. Kubik was joined in 1930 by the psychiatrist-neurologist-neuropathologist Stanley Cobb (1887–1968), who had started the Harvard Neurological Unit at the BCH and who became the chair of Psychiatry at MGH. Subsequently, the neurologist-neuropathologist Raymond D Adams (1911–2008) (Figure 2), who had trained at BCH and who had been on the faculty there for a number of years, moved to the MGH in 1951 to become the chief of Neurology, a position he held until 1977. He was the Bullard Professor of Neuropathology at Harvard and was one of the leading neurologists of the second half of the twentieth century45—one of the ‘triumvirate’ of great MGH neurologist-neuropathologists of that era: Adams, C Miller Fisher (1913–2012) and EP Richardson, Jr (1918–1998).47

The BCH department also provided important seeds for the development of neuropathology in other hospitals in Boston, particularly the psychiatric and state hospital system. An important trainee of FB Mallory who, despite his relatively short life, influenced the pathology (primarily neuropathology) being done at the various psychiatric and state hospitals in the Boston area was Elmer Ernest Southard (1876–1920) (Figure 17). Southard was reportedly a wonderful teacher. Among his colleagues and those who followed him at these hospitals were individuals who contributed in major ways to neuropathology, particularly maldevelopmental, metabolic, and inherited conditions: Myrtelle Canavan (1879–1953) (Figure 17), whose name today is mostly remembered for Canavan disease; Harry C Solomon (1889–1982) (Figure 17), a psychiatrist who co-authored important books on syphilis, first (in 1917) with EE Southard and later (in 1946) with Raymond Adams and H Houston Merritt when both were at BCH; and indirectly, Paul Yakovlev (1894–1983), who was an enormously productive individual, having amassed a collection of some 250 000 slides by the time his collection was transferred to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Of Southard, Canavan wrote that he ‘had in his short life of 43 years a great inspirational effect on his students and friends. His remarkable memory for events and the literature, his sympathy and open mind, the mental shower bath effect his lectures and demonstrations had, made for him grateful, admiring friends and firm adherents. Many a logically trained mind felt new impetus because of the contact, however brief, and very few have left the field of neuro-psychiatry who were his pupils in it’.48 Indeed, so devoted was Canavan to her mentor that she eventually published an entire monograph on post-mortem analysis of Southard’s brain as well as the brains of Southard’s parents!49

Pathologists from the Massachusetts state hospitals photographed in 1917. These hospitals contributed significantly to the practice of pathology, particularly neuropathology. Notable in the picture are Drs Elmer Ernest Southard (third from right at the front), Harry C Solomon (left) and Myrtelle Canavan (second from left).

Pathology at Tufts University began with Timothy Leary (1870–1950?) (Figures 2 and 18). Leary had been the first trainee of FB Mallory at the BCH. He moved to Tufts in 1900 and was the head of Pathology there until 1929. During this time, he ran a private laboratory at the medical school and, for unclear reasons in 1929, fell out with the medical school. He returned to the Mallory Institute and was a medical examiner there through the 1930s and 1940s, when he was widely recognized as an authority in forensic medicine. Following Leary at Tufts was H Edward MacMahon (1901–1996) (Figures 2 and 19). He was originally from Aylmer, Ontario, and received his medical degree from the University of Western Ontario in 1925. He trained at the Montreal General Hospital before coming to train further with FB Mallory at the BCH. MacMahon had broad clinical interests and wrote papers on a variety of topics, chiefly in hepatic, renal, pulmonary and vascular pathology. He was a highly respected member at Tufts, and was known for his gentle demeanor but insistence on quality; John S McGovern, on the occasion of Dr MacMahon’s retirement, wrote that he was ‘a modest gentleman at all times and a man of the strictest personal integrity, he has no use for cant or hypocrisy... (Figures 2 and 18). An endearing quirk of his character is an inability to endure the pompous who, in his presence, are often annihilated with such urbane delicacy that they fail to notice their own execution’.50 MacMahon himself stressed work-life balance, writing that ‘I have learned that your family must come first and then, and only then, will your practice take care of itself. And I have learned that marriage to a cause or to an institution is a poor substitute for the real thing’.50 Remarkably, he was the chair of Pathology at Tufts for over four decades, from 1930 until 1971. Thus, between Leary and MacMahon, two trainees of FB Mallory chaired Tufts Pathology for seven decades.

Shields Warren (1898–1980) (Figures 2 and 20) graduated from Boston University, with which his family had a long and distinguished history. He received his medical education at HMS and was inspired to go into pathology by Wolbach (see below). He then trained with FB Mallory at the BCH. Following his training, he opted to join the New England Deaconess Hospital, because of the renown of its primary surgeon, Frank Lahey (of Lahey Clinic fame), and internist and diabetologist, Elliot Joslin. Warren was to spend 50 years at the New England Deaconess Hospital, 36 of them as chief of Pathology. Given his early work with Joslin, he wrote a number of papers on the pathology of diabetes, but most of his scholarly output was in the area of cancer research. He was a nationally and internationally recognized expert in the biological effects of radiation, doing seminal work relating to the atomic bomb effects at the end of World War II, serving as a consultant to the US government on the effects of radiation. He also had a particular interest in endocrine pathology, publishing a number of key books in the area. His illustrious pupil and successor, William Meissner, said of him at his passing, ‘We are grateful for the privilege of having had this fine gentleman with his quiet dignity among us. May his way of life continue to live within us all.’51

Dr Shields Warren (right) and Dr Olive Gates (left) with an unidentified man behind them. Reproduced with permission from Scully RE, Vickery AL Jr, Surgical Pathology at the Hospital of Harvard Medical School, in Guiding the Surgeon’s Hand, Rosai J ed, Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology 1997.

Olive Gates (1901?–1999) (Figure 20) was an important diagnostic pathologist in the early-to mid-twentieth century in Boston, an expert in both surgical pathology and cytopathology who was based at the New England Deaconess Hospital with Shields Warren. She was a central pathologist for Tumor Diagnostic Services, a free state cancer unit at HMS that participated in the running of the Pondville Hospital, the state cancer hospital.52 (Of note, in this capacity, she was an early teacher of Robert E Scully, a mentor to two of the authors, DNL and RHY.) Gates wrote one of the early articles (1945) and handbooks (1947) (Figure 21) on cervical cytopathology,53, 54 along with Drs Warren (with the introduction to the handbook written by Dr Papanicolaou), and was the first woman awarded a gold medal for distinguished service by the Massachusetts chapter of the American Cancer Society.55

S Burt Wolbach and His Influence

One particularly important offshoot of the FB Mallory-BCH training lineage featured S Burt Wolbach (1880–1954) (Figure 22), given that Wolbach himself had extensive influence on many individuals in the Boston pathology community. Originally from Nebraska, he came to Boston during his schooling, graduating from HMS in 1903. He trained in pathology at the BCH with Drs FB Mallory and Councilman and spent a few years as the pathologist at the Long Island Hospital in Boston and at the Boston Lying-in Hospital. Following a year in Albany, NY, and another in Montreal, he returned to Boston in 1908. Wolbach had a remarkable career, serving as the chief of pathology at Children's (1915), Boston Lying-in (1916), and Peter Bent Brigham (1916) hospitals and HMS (1922)—all until his retirement in 1947. He was a colorful personality, wearing a red carnation in his lapel each day and riding his horse each morning before coming to work.5 He was widely praised to one of us (RHY) by Dr Robert Scully, who took every opportunity to acknowledge Dr Wolbach for both his professional attributes and personal characteristics.

Wolbach’s scientific interests were in infectious diseases and vitamin deficiencies. Of particular note was his seminal work, some in the laboratory and some in the field in Montana, on the Rickettsia that causes Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, studies characterized by extraordinary care and attention to detail.56 As stated recently, his papers ‘shed light on the workings of an inquisitive and organized mind, with strong interests and roots in natural history, as it sought answers to complicated biomedical riddles’.57 Wolbach achieved national recognition for his work, and was the president of the American Association of Pathologists and Bacteriologists in 1936 and of the Society for Experimental Pathology in 1937. When he served as head of pathology at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, he had mixed relationships with the head of surgery, the neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing (1869–1939). Although Wolbach believed that Cushing should be judged on the basis of his remarkable ability to serve his patients,58 Cushing only grudgingly shared his specimens with the Pathology department.5 The upside of this was that it encouraged some talented neurosurgeons, such as Percival Bailey (1892–1973) and Louise Eisenhardt (1891–1967), to focus their scholarly activities on the neuropathological basis of brain tumor classification along with Cushing; these collaborations led to the basis of current glioma (Bailey and Cushing) and meningioma (Cushing and Eisenhardt) classifications.

Wolbach influenced Boston pathology in major ways through teaching and research, attracting many individuals into the field, including Shields Warren (see above), Sidney Farber and Arthur Hertig (see below), as well as Monroe Schlesinger (1892–1955) (Figure 23). Schlesinger trained with Wolbach, first as an HMS student and then as a resident at the Peter Bent Brigham and Children’s Hospitals, and at BCH. He became the first chair of Pathology at Beth Israel Hospital, where he served from 1929 to 1955. It was said of him that ‘however complex and complicated his mind, his skillful hands created technics of exceptional simplicity and effectiveness’.59 He was known for his meticulous approach to his scientific studies, particularly the novel injection methods that he used to study the coronary arteries60—studies that, with Paul Zoll, formed the basis of modern coronary angiography and that elucidated the pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. A year before his death, he was honored on the occasion of his 25th anniversary with the Beth Israel Hospital. On that occasion, Wolbach, who was 74 at the time, said, ‘Your proof that adequate anastomotic circulation could develop while the coronary arteries were undergoing closure will always remain as an outstanding contribution and one that should call attention to the desirability of a continuous regimen of exercise as one grows older.’ He added, somewhat tongue in cheek, ‘Personally, I am grateful because I have felt justified in doing all the things by way of exercise that are usually condemned for a person of my age.’59 (Sadly, however, Wolbach died that year.)

Sidney Farber (1903–1973) (Figure 24) had graduated from HMS in 1927 and trained at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital with Wolbach and with FB Mallory at the BCH and was appointed by Wolbach as the first full-time pathologist at Children’s Hospital in 1929.61 His early interests relating to pathology focused on congenital heart disease, cystic fibrosis, encephalitis, histiocytosis, and pediatric tumors but his interests were broad and included autopsy pathology, on which he wrote a monograph (Figure 25). It was pediatric cancer, however, that commanded Farber’s main interest and remarkable energy increasingly during his career, and he is chiefly remembered today as a true pioneer in the development of effective chemotherapy for cancer, with his first paper on this subject appearing in 1948,62 and in raising funds locally and nationally to support cancer research.63 In this capacity, his name remains today as part of one of the large cancer centers in Boston: the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Orvillle Bailey, who had trained with Wolbach and Farber, said of Farber, ‘Yet with all the driving force that he put into pursuit of these aims, he was a gentleman, one who appeared relaxed even in the most tense situations. His technics were diplomacy and persuasion, never heavy-handed tactics. There was a ready sense of humor,’ and Bailey added humorously, ‘he was a discriminating connoisseur of detective fiction’.61

Arthur T Hertig (1904–1990) (Figures 2 and 26) trained with Wolbach and Farber and was asked by Wolbach to organize the pathology laboratory at the Boston Lying-In Hospital, where Hertig was the chief of Pathology for 34 years, from 1934 to 1968. He was also the pathologist for the Free Hospital for Women from 1938 to 1968. Given the institutions with which he was affiliated, he naturally became an expert in gynecological, obstetrical, and perinatal pathology, with his well-known ‘egg hunts’ providing key information that was to inform the work of his colleague, John Rock, in developing a contraceptive ‘pill’. He published important AFIP fascicles on gynecological tumors.64 His lifetime study of gynecological issues resulted in his humorously named autobiographical piece, published in 1973, Forty Years in the Female Pelvis. An Unusual Case of Prolonged Dystocia.65 Indeed, he was known for his humor, in addition to his dedication to medical students and his faculty.66 Hertig served as the chair of the overall HMS pathology department from 1952 to 1968. Even after his ‘retirement,’ he kept active in research, serving as the primary pathologist at the New England Regional Primate Research Center from 1968 until 1989.67

Summary

Following the pioneering work of the physician-pathologists at the MGH in the middle to late decades of the 19th century and the development of novel technologies in laboratory medicine, a need arose for full-time pathologists in Boston. The growth of a dedicated discipline of pathology in Boston followed the recruitment of William Councilman from Baltimore in 1892. Councilman provided a nidus that fostered the remarkable careers of Frank Burr Mallory and James Homer Wright; in combination, these three planted the clinical, educational, and research seeds that were to blossom in Boston in the 20th century. The subsequent emergence of multiple teaching hospitals in the Boston area at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries then provided remarkable opportunities for the next generation of pathologists, perhaps most notably S Burt Wolbach, whose influence inspiring pathologists approached that of Frank Burr Mallory. Each of these new departments would attract a cadre of exceptional academic pathologists in the second half of the 20th century. And, as we strive to adapt to the accelerating pace of medical and scientific innovation in this new century, we trust that the legacies of these past generations of Boston pathologists will continue to inspire the practice of pathology and laboratory medicine for years to come.

References

Louis DN, Young RH . Keen Minds to Explore the Dark Continents of Disease: A History of the Pathology Services at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Massachusetts General Hospital: Boston, MA, USA, 2011.

Young RH, Louis DN . The Warrens and other pioneering clinician pathologists of the Massachusetts General Hospital during its early years: an appreciation on the 200th anniversary of the hospital founding. Mod Pathol 2011;24:1285–1294.

Flexner S, Flexner JT . William Henry Welch and the Heroic Age of American Medicine. The Viking Press: New York, NY, USA, 1941, pp 539.

Cushing H . William Thomas Councilman. Science 1933;77:613–618.

Scully RE, Vickery AL Jr . Surgical pathology at the hospitals of Harvard Medical School. In: Rosai J (ed) Guiding the Surgeon’s Hand. American Registry of Pathology: Washington, DC, USA, 1997.

Wolbach SB . Obituary: William Thomas Councilman 1854-1933. Arch Pathol 1933;16:114–119.

Leary T . Frank Burr Mallory and the pathological department of the Boston City Hospital. Am J Pathol 1933;9:659–72.3.

Young RH, Lee RE . James Homer Wright (1869-1928). In: Louis DN, Young RH (eds). Keen Minds to Explore The Dark Continents of Disease: A History of the Pathology Services at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Massachusetts General Hospital: Boston, MA, USA, 2011, pp 41–47.

Councilman WT . A lecture delivered to the second year class of the Harvard Medical School (Last lecture as teacher of undergraduate medicine). In: History of Medicine Archives, Countway Library, Harvard Medical School, 1921.

Councilman WT . The malarial germ of Laveran. Public Health Pap Rep 1887;13:224–232.

Councilman WT, Abbott AC . Contribution to the pathology of malarial fever. Am J Med Sci 1885;89:416–428.

Councilman WT . Histology of yellow fever. In: GM Sternberg (ed). Report on the Etiology and Prevention of Yellow Fever: US Public Health Service. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, 1887.

Councilman WT, Lafleur HA . Amoebic dysentery. Johns Hopkins Hospital Reports 1891;2:395–548.

Councilman WT, Mallory FB, Wright JH . Cerebro-spinal meningitis and its relation to other forms of meningitis. J Boston Soc Med Sci 1898;2:53–57.

Councilman WT, Mallory FB, Pearce RM . A study of the bacteriology and pathology of two hundred and twenty fatal cases of diphtheria. J Boston Soc Med Sci 1900;5:139–319.

Councilman WT . Some general considerations on the pathology of smallpox. Public Health Pap Rep 1905;31:218–229.

Councilman WT, Magrath GB, Brinckerhoff WR . The pathological anatomy and histology of variola. J Med Res 1904;11:12–135.

Councilman WT, Lambert RA . The Medical Report of the Rice Expedition to Brazil. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 1918.

Councilman WT . The root system of epigaea repens and its relation to the Fungi of the Humus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1923;9:279–285.

Freeman W . Frank Burr Mallory: a doctor of physicians. New Engl J Med 1944;231:824–828.

Parker JR . Frank Burr Mallory. Am J Pathol 1941;17:785–786.

Cheever DW MA, Gay GW, Blake JB . A History of Boston City Hospital, from its Foundation to 1904. Boston Municipal Printing Office: Boston, 1906.

Mallory FB . The Pathological Department of Boston City Hospital. In: Cheever DW MA, Gay GW, Blake JB (eds). Boston Municipal Printing Office: Boston, 1906.

Mallory FB, Wright JH . Pathological Technique: A Practical Manual for Workers in Pathological Histology and Bacteriology. WB Saunders: Philadelphia, 1895.

O'Brien MJ . Reflections on a textbook of pathology published 100 years ago and its author Frank Burr Mallory. ACESO: J Boston Univ Med School Historical Society 2015;3:30–37.

Mallory FB . The results of the application of special histological methods to the study of tumors. J Exp Med 1908;10:575–593.

Mallory FB . The Principles of Pathologic Histology. WB Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1914.

Mallory FB . A histological study of typhoid fever. J Exp Med 1898;3:611–638.

Mallory FB . Scarlet fever. Protozoon-like bodies found in four cases. J Med Res 1904;10:483–492.

Mallory FB, Medlar EM . The skin lesion in measles. J Med Res 1920;41:327–48 13.

Mallory FB . Phosphorous and alcoholic cirrhosis. Am J Pathol 1933;9:557–568.

Mallory FB . Cirrhosis of the liver. Five different types of lesions from which it may arise. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 1911;22:69–75.

Louis DN, Young RH . The Wright Era (1896-1926). In: Louis DN, Young RH (eds). Keen Minds to Explore The Dark Continents of Disease: a History of the Pathology Services at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Massachusetts General Hospital: Boston, 2011, pp 20–41.

Wright JH, Minot GR . The viscous metamorphosis of the blood platelets. J Exp Med 1917;26:395–409.

Wright JH, Joslin EP . Degeneration of the islands of Langerhans of the pancreas in diabetes mellitus. J Med Res 1901;6:360–365.

Lee RE, Young RH, Castleman B . James Homer Wright: a biography of the enigmatic creator of the Wright stain on the occasion of its centennial. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:88–96.

Wright JH . A rapid method for the differential staining of blood films and malaria parasites. J Med Res 1902;7:138–144.

Wright JH . The origin and nature of blood plates. Boston Med Surg J 1906;154:643–645.

Wright JH . A case of multiple myeloma. J Boston Soc Med Sci 1900;10:195–204.

Wright JH . Neurocytoma or neuroblastoma, a kind of tumor not generally recognized. J Exp Med 1910;12:556–561.

Wright JH . The biology of the microorganism of Actinomycosis. J Med Res 1905;13:349–404.

Wright JH, Richardson O . Treponemeta (Spirochaetae) in syphilitic aortitis, 5 cases, one with aneurysm. Boston Med Surg J 1903;160:539–541.

Councilman WT . Obituary: James Homer Wright. Arch Pathol 1928;5:493–495.

Jackson H, Parker F . Hodgkin’s Disease and Allied Disorders. Oxford University Press: New York, 1947.

Laureno R . Raymond Adams: a Life of Mind and Muscle. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2009.

Mallory GK, Weiss S . Hemorrhages from lacerations of the cardiac orifice of the stomach due to vomiting. Am J M Sci 1929;178:506.

Hedley-Whyte ET, Louis DN, De Girolami U et al. Neuropathology. In: Louis DN, Young RH (eds). Keen Minds to Explore The Dark Continents of Disease: A History of the Pathology Services at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Massachussetts General Hospital: Boston, MA, USA, 2011, pp 20–41.

Estes ML . Myrtelle Canavan. In: Ashwal S (ed) Founders of Child Neurology. Norman Publishing: San Francisco, CA, 1990, pp 437–442.

Canavan MM . Ernest Elmer Southard and his parents: a brain analysis. Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1925.

McGovern JS . H. Edward MacMahon, MD, MRCP, ScD. Arch Pathol 1970;89:487–490.

Wood DA . A personal tribute to Shields Warren, M.D. (1898-1980). CA Cancer J Clin 1980;30:348–349.

Parker GL . The Pondville State Cancer Hospital, 1927-1947. New Engl J Med 1948;238:800–804.

Gates O, Warren S . The vaginal smear in diagnosis of carcinoma of the uterus. Am J Pathol 1945;21:567–601.

Gates O, Warren S . A Handbook for the Diagnosis of Cancer of the Uterus by the Use of Vaginal Smears. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1947.

Gazette HU, Gates, Former Professor of Pathology, Dies at 98 1999 (25 October 2105). Available from http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/1999/08.19/obits.html.

Woodward TE, Walker DH, Dumler JS . The remarkable contributions of S. Burt Wolbach on rickettsial vasculitis updated. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 1992;103:78–94.

Musser JM . S. Burt Wolbach, Rocky mountain spotted fever, and blood-sucking arthropods: triumph of an early investigative pathologist. Am J Pathol 2013;182:291–293.

Bliss M . Harvey Cushing: A Life in Surgery. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2005.

Farber S, Reiner L, Warren S . Memorial to Dr Schlesinger. New Engl J Med 1955;252:963–964.

Schlesinger MJ . An injection plus dissection study of coronary artery occlusions and anastomoses. Am Heart J 1938;15:528–568.

Bailey OT . Sidney Farber, MD, 1903-1973. Am J Pathol 1974;77:129–134.

Farber S, Diamond LK, Mercer RD et al. Temporary remissions in acute leukemia in children produced by folic acid antagonist, 4-aminopteroyl-glutamic acid. New Engl J Med 1948;238:787–793.

Mukherjee S . The Emperor of All Maladies: a Biography of Cancer. Scribner: New York, NY, 2011.

Hertig AT, Gore H . Tumors of the Female Sex Organs (In Three Parts, I Hydatidiform Mole and Choriocarcinoma, II Tumors of the Vulva, Vagina and Uterus, III Tumors of the Ovary and Fallopian Tube). American Registry of Pathology: Washington, DC, 1956–1961.

Hertig AT . Forty years in the female pelvis. An unusual case of prolonged dystocia. Obstetrics Gynecol 1973;42:907–909.

Gruhn JG, Gore H, Roth LM . Dr Arthur T. Hertig. Int J Gyn Pathol 1998;17:183–189.

Scully RE, Hertig A . An interview with Arthur Hertig. Interview by Robert E. Scully. Am J Clin Pathol 1988;90:366–370.

Karlson AG . William Hugh Feldman, DVM, 1892-1974. Am J Pathol 1975;78:2–5.

Acknowledgements

The content of this paper is derived from the authors’ lectures at the 2015 meeting of the History of Pathology Society, held in Boston, MA, USA, on 22 March 2015. The authors acknowledge the wonderful photographic portraits of Dr William Feldman,68 which he generously gifted to the National Library of Medicine. We also thank the archives collections at HMS, Tufts University and the National Library of Medicine, as well as Mr Kenneth Mallory for his interest and his permission to use family photographs of his grandfather, FB Mallory, and father, G Kenneth Mallory, and of Frederic Parker; and Dr Harry Kozakewich of Boston Children’s Hospital for sharing the frontispiece of Dr Farber’s book on the autopsy. Finally, we note the prior contributions of four individuals whose interest in history and resultant research uncovered invaluable information: Dr Robert Lee of Pittsburgh, who became fascinated by the life of Dr James Homer Wright, a native of Pittsburgh, and garnered the attention of Dr Benjamin Castleman, enabling a detailed inquiry into Dr Wright’s life; and Drs Austin L Vickery, Jr and Robert E Scully, whose essay on the history of surgical pathology at the hospitals of HMS and whose historical collections here at MGH, constitutes a remarkable wealth of information.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Louis, D., O'Brien, M. & Young, R. The flowering of pathology as a medical discipline in Boston, 1892-c.1950: W.T. Councilman, FB Mallory, JH Wright, SB Wolbach and their descendants. Mod Pathol 29, 944–961 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.91

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.91