Abstract

Recent genetic analyses using next-generation sequencers have revealed numerous genetic alterations in various tumors including meningioma, which is the most common primary brain tumor. However, their use as routine laboratory examinations in clinical applications for tumor genotyping is not cost effective. To establish a clinical sequencing system for meningioma and investigate the clinical significance of genotype, we retrospectively performed targeted amplicon sequencing on 103 meningiomas and evaluated the association with clinicopathological features. We designed amplicon-sequencing panels targeting eight genes including NF2 (neurofibromin 2), TRAF7, KLF4, AKT1, and SMO. Libraries prepared with genomic DNA extracted from PAXgene-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues of 103 meningioma specimens were sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq. NF2 loss in some cases was also confirmed by interphase-fluorescent in situ hybridization. We identified NF2 loss and/or at least one mutation in NF2, TRAF7, KLF4, AKT1, and SMO in 81 out of 103 cases (79%) by targeted amplicon sequencing. On the basis of genetic status, we categorized meningiomas into three genotype groups: NF2 type, TRAKLS type harboring mutation in TRAF7, AKT1, KLF4, and/or SMO, and ‘not otherwise classified’ type. Genotype significantly correlated with tumor volume, tumor location, and magnetic resonance imaging findings such as adjacent bone change and heterogeneous gadolinium enhancement, as well as histopathological subtypes. In addition, multivariate analysis revealed that genotype was independently associated with risk of recurrence. In conclusion, we established a rapid clinical sequencing system that enables final confirmation of meningioma genotype within 7 days turnaround time. Our method will bring multiple benefits to neuropathologists and neurosurgeons for accurate diagnosis and appropriate postoperative management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Meningioma, arising from meningothelial cells, is the most common primary brain tumor and accounts for about 25% of all intracranial tumors.1 Although most such tumors are categorized as World Health Organization (WHO) grade I, these histopathologically benign tumors sometimes recur despite complete surgical resection.2 In fact, the 10 year recurrence rate of WHO grade I meningioma after gross total resection reaches 15–20%.3 Moreover, atypical (grade II) or anaplastic (grade III) meningiomas, which account for about 20% of all meningiomas,2 show a more aggressive clinical course; 50% and 80% of WHO grade II and III meningiomas recur within 5 years, respectively.4 Recurrent meningiomas often become resistant against surgery or radiation therapy. Therefore, appropriate evaluation of the recurrent risk at initial diagnosis is important.

The development of next-generation sequencers has enabled researchers to perform genetic investigations of various tumors, resulting in the discovery of numerous clinically relevant mutations and/or copy-number alterations. Loss of neurofibromin 2 (NF2) has been found in about half of sporadic meningiomas,5, 6, 7 and mutations in TRAF7, KLF4, AKT1, and SMO were recently reported in non-NF2 meningiomas by next-generation sequencing.8 Loss of NF2 has been evaluated mainly by karyotyping,9 comparative genomic hybridization,10 fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH),11 single-nucleotide polymorphism array,11 and quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis;12 and additional genetic analyses are required to investigate mutations in other genes. The combination of these methods leads to increased cost and number of days required for analysis, so the application of these techniques for regular laboratory examinations remains to be established.

In this study, we performed targeted amplicon sequencing of 103 meningioma specimens and evaluated the association with genotype and clinicopathological features using the desktop sequencer MiSeq, and established a clinical sequencing system for meningioma to determine the genotype as a routine laboratory examination in addition to concurrent pathological diagnosis.

Materials and methods

Patients

Frozen tumor samples of 103 patients surgically resected in 1988–2015 were used for genetic analyses. Clinicopathological features are summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1. The patients included 31 men and 72 women with a median age of 55 years (range 15–87) at surgery. Eighty-two samples were newly diagnosed meningiomas and twenty-one were recurrent meningiomas, eight of which were specimens obtained after radiation therapy. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry with a monoclonal anti-Ki-67 antibody (1:100 dilution, clone MIB-1, M7240, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) were performed with PAXgene-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue obtained from the snap-frozen specimens in all cases and corresponding formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue in some cases. Histological diagnosis was reviewed according to the current WHO classification 2007 (ref. 13) by two experienced pathologists (S. Yuzawa and H. Nishihara). Among the 82 patients with newly diagnosed meningioma, preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) information was obtained from 72 patients. Clinical follow-up data were obtained from 90 patients. Recurrence-free survival in the recurrent specimens was measured by the time from the first operation to the recurrence. Sampling, storage, and analysis of the tumor samples included in this study were approved by the Internal Review Board on Ethical Issues of Hokkaido University Hospital and Graduate School of Medicine, Sapporo, Japan. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in this study.

DNA Extraction and Quantification

Frozen tumor samples (median size in diameter 7 mm, range 2.5–12) were fixed with PAXgene Tissue System (PreAnalytiX, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland) and embedded in paraffin according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Genomic DNA was extracted from PAXgene-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues using the PAXgene Tissue DNA Kit (PreAnalytiX), following the manufacturer’s instructions. For the control of copy-number alterations, genomic DNA was extracted from the blood of three healthy volunteers using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The quality of genomic DNA was assessed using the Qubit dsDNA BR assay kit and the Qubit fluorometer 2.0 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and the GeneRead DNA QuantiMIZE Assay Kit (Qiagen).

Targeted Amplicon Sequencing and Data Analysis

An amplicon-sequencing panel targeting the entire exonic sequence of six genes (NF2, AKT1, SMO, ERBB2, KIT, and MET) was designed by a GeneRead Mix-n-Match panel (181905 MNGHS-00062X-296; Qiagen) and a custom panel targeting the whole exon of TRAF7 and partial exon of KLF4 (targeting KLF4 K409Q) was generated by a GeneRead Custom panel (181902 CNGHS-00120X-44; Qiagen). The GeneRead DNAseq Targeted Panel V2 (Qiagen) was used for library preparation with 59–473 ng of genomic DNA following the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of libraries was assessed using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer and Agilent DNA 1000 Kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and the GeneRead Library Quant Kit (Qiagen). The libraries were sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq to produce 150-bp paired-end reads.

The raw read data obtained from amplicon sequencing were processed by online analytical resources from the GeneRead DNAseq Variant Calling Service (http://ngsdataanalysis.sabiosciences.com/NGS2/) for analysis of mutations and copy-number alterations. In addition, BAM files obtained from the GeneRead DNAseq Variant Calling Service were processed by BioReT System (Amelieff, Tokyo, Japan) for analysis of mutations. In BioReT System, BAM files were realigned and recalibrated with the GATK (Genome Analysis Toolkit; version 1.6.13), using RealignerTargetCreator, IndelRealigner, CountCovariates, and TableRecalibration. Single-nucleotide variants and small indels were detected using the GATK UnifiedGenotyper, followed by filtering for low-quality variants using the GATK VariantFiltration. All analyses were performed with default settings except for the minIndelFrac parameter for indel call using GATK UnifiedGenotyper, which was set to 0.05. After variant detection, VCF files were annotated by SnpEff genetic variant annotation and effect prediction toolbox (version 4.0). Information about Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database (version 72) and IntOGen (version 1412) was annotated using SnpSift, a package tool of SnpEff, to VCF and variants on targeted genes were extracted. Single-nucleotide variants were limited to protein-altering mutations at ≥10% variant frequency with read depth of >100. Germline variants, except in the NF2 gene, were manually excluded according to variant frequency and by referencing to dbSNP and Human Genetic Variation Database.

FISH Analysis

The formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues of 35 tumors were examined by interphase-FISH (I-FISH) with commercially available probes for 22q (FG0003, Abnova, Taipei, Taiwan). For microscopic evaluation, 200 interphase nuclei were examined for each specimen.

Statistical Analysis

Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance test with the Steel–Dwass test for post hoc determination and χ2 analysis were performed to analyze the correlations between mutation subtype and clinical data. For survival analysis, Kaplan–Meier analysis and the log-rank test were used. Cox proportional hazards model was used for univariate and multivariate survival analysis to adjust for covariates of statistical significance, including age, sex, Simpson grade, WHO grade, and genotype. Analyses were performed on Ekuseru-Toukei 2015 (Social Survey Research Information, Tokyo, Japan) and JMP version 11.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Copy Number Alteration Analyses by Next-Generation Sequencing and FISH

The results of I-FISH were available in 34 out of 35 samples investigated. Nineteen cases (56%) displayed a diploid karyotype. Thirteen cases (38%) showed monosomy 22 in 60–100% of the interphase nuclei, whereas del(22q) was observed in 12–20% of the interphase nuclei in the other two cases (6%) (Supplementary Figure 1; Supplementary Table 2).

In copy-number variant calling workflow of next-generation sequencing, 71 of 103 cases (69%) showed a score Q of NF2 above 50, indicating strong evidence for NF2 loss.14 One case displayed a pattern of biallelic loss (Supplementary Figure 1J); I-FISH was not applicable to this case because of the age of the formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue (obtained in 1996).

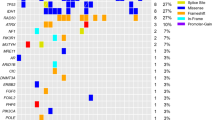

The receiver operating characteristic curve for next-generation sequencing against I-FISH is shown in Supplementary Figure 2. The area under the curve was 0.783. The score Q=79 presented maximum Youden index with sensitivity as 86.7% and specificity as 73.7%. The positive rates in the 34 cases whose results of I-FISH were available were 52.9% using next-generation sequencing and 44.1% using I-FISH. Cases with discordant results between next-generation sequencing and I-FISH (next-generation sequencing positive, I-FISH negative in five cases; next-generation sequencing negative, I-FISH positive in two cases) displayed no difference in score Q or score P compared with cases with concordant results (Supplementary Figure 1K–R). Overall, 62 of 103 cases (60%) showed NF2 loss when using the cutoff value (score Q≥79). Twenty-six copy-number alterations of AKT1, SMO, MET, KIT, and ERBB2 genes were observed in 22 cases (21%) based on next-generation sequencing, but the accuracy of copy-number alterations in these genes was not confirmed by I-FISH. Loss of AKT1, KIT, SMO, and MET were detected in four, four, five, and five of 103 cases, respectively, whereas amplification of KIT, MET, and ERBB2 were observed in three, four, and one cases, respectively (Figure 1; Supplementary Table 2).

Genotype and clinicopathological findings. Samples from patients were separated according to genotype. At the top of the figure, the clinical features are summarized. In the middle portion of the figure, copy-number alterations and mutations are shown. At the bottom of the figure, the pathological findings are presented. CNA, copy-number alteration; FISH, fluorescent in situ hybridization.

Mutation Analysis

In total, 71 protein-altering mutations were detected in 57 out of 103 cases (55%; Figure 1; Supplementary Table 3). Thirty-nine cases (38%) harbored NF2 mutations, and one of these cases carried two different frameshift mutations. Mutation types of NF2 were variable: frameshift mutation in 19 cases, splice region mutation in 10 cases, nonsense mutation in nine cases, and in-frame deletion in one case. Thirty-eight of 62 cases (61%) with NF2 loss simultaneously carried NF2 mutation (Figure 2a). Two tumors from the patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 carried both NF2 loss and NF2 mutation. Two of three patients with radiotherapy-induced meningioma carried NF2 loss, one of which harbored concomitant mutation in NF2, whereas the other patient did not show any mutations or NF2 loss. Missense mutations in TRAF7, KLF4, AKT1, and SMO were observed in 16 (16%), eight (8%), five (5%), and one (1%) cases, respectively (Figures 1 and 2a). All AKT1 and KLF4 mutations corresponded to E17K and K409Q mutations, respectively. KLF4 K409Q always co-occurred with mutations of TRAF7. AKT1 E17K was accompanied by TRAF7 mutation in all but one case, which was the case of chordoid meningioma (Supplementary Figure 3E). With regard to mutation in TRAF7, the reproducible mutations, TRAF7 N520S and R641H, were detected in five and two cases, respectively, whereas the other nine mutations differed from each other. Nine of 11 mutations in TRAF7 mapped to the WD40 domains. Mutations in TRAF7, KLF4, AKT1, and SMO were mutually exclusive of NF2 mutation and NF2 loss. Consequently, 81 out of 103 cases (79%) carried at least one or more gene alterations including mutations in the five genes and/or NF2 loss. No somatic mutation was detected in KIT, MET, or ERBB2. These analyses of mutation and copy-number alterations could be completed within 7 days from tumor tissue fixation.

Genotype and clinical features. (a) The frequency of each gene alteration. The number indicates the number of cases carrying each gene alteration. (b) Tumor location and genotype. Two cases of intraventricular meningioma were excluded. (c) Tumor volume according to genotype. Newly diagnosed meningiomas were analyzed (n=65). Box plots show the median (horizontal line), first to third quartiles of size (box) and 1.5 times the interquartile range (whiskers). (d) Genotype and recurrence-free survival. Ninety cases of newly diagnosed and recurrent meningiomas were analyzed.

Clinicopathological Analysis Based on Genotype

To investigate the relationship between clinicopathological features and genotype, we classified meningioma into three categories based on genotype obtained by next-generation sequencing: NF2 type, TRAKLS type, and ‘not otherwise classified’ (NOC) type. NF2 type included cases with NF2 loss and/or NF2 mutation. TRAKLS type includes cases with mutation in TRAF7, AKT1, KLF4, and/or SMO, and NOC type included cases without any mutation or NF2 loss in our panel. We classified two cases with loss of AKT1 or SMO but no other mutations into NOC type rather than TRAKLS type, because the loss of these genes usually causes loss of function, whereas mutations of AKT1 (E17K) or SMO (W535L and L412F) found in TRAKLS type have been considered to activate each downstream signaling.

Statistical analysis revealed that genotype was associated with tumor location (P=0.013, χ2 analysis,). About 80% of tumors in calvarium were classified as NF2 type (Figure 2b; Supplementary Figure 3A–B), while tumors of TRAKLS type were frequently localized in the skull base (15/18 cases, 83%; Table 1; Figure 2b; and Supplementary Figure 3C–F). In addition, the size of the tumors in NF2 type was significantly larger than that of those in TRAKLS type (median tumor size 50.3 vs 14.2 ml, respectively; P<0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test; Figure 2c). The difference in tumor size of NF2 type and TRAKLS type was also statistically significant when limited in the skull base meningiomas (median tumor size 53.9 vs 13.0 ml, respectively; P<0.001). Genotype showed relationships with some imaging characteristics. Calcification (P=0.006, χ2 analysis), adjacent bone change (P=0.001) and heterogeneous gadolinium enhancement (P=0.001) were more frequently observed in tumors of NF2 type (Table 2). Age and sex were not associated with genotype (Table 1).

Genotype also correlated with histological features. All 23 fibrous meningioma cases, including one case with brain invasion, were classified as NF2 type. All seven cases with secretory components were categorized as TRAKLS type, especially with duplicated mutations in both TRAF7 and KLF4. In contrast, a microcystic component was not observed in TRAKLS type. Ki-67 labeling index (LI) of NF2 type was significantly higher compared with TRAKLS type (P=0.002, Kruskal–Wallis test). Meningiomas of WHO grade II and III were more likely to be NF2 type (56% in WHO grade I vs 78% in WHO grade II and III), but this was not statistically significant.

Prognostic Analyses

Among the 90 patients with clinical follow-up data available, the median follow-up time was 25.1 months (range 1–310) with a median recurrent time of 38.3 months (range 2.5–272). Thirty out of 90 cases (33%) underwent tumor recurrence (25/52 (48%) of NF2 type, 0/18 (0%) of TRAKLS type, and 5/20 (25%) of NOC type) and nine of 88 cases (10%) were deceased (8/50 (16%) of NF2 type, 0/18 (0%) of TRAKLS type, and 1/20 (5%) of NOC type).

On the basis of Kaplan–Meier analysis, recurrence-free survival for patients of TRAKLS type was significantly better compared with NF2 and NOC type (P=0.037, log-rank test; Figure 2d). The median recurrence-free survival of NF2 type and NOC type was 3.39 and 12.41 years, respectively. The median recurrence-free survival had not been reached at the time of analysis in patients with TRAKLS type because no one underwent tumor recurrence. The patients with lower Simpson grade (Simpson grade 1–2) and those with WHO grade I showed longer recurrence-free survival than those with higher Simpson grade (Simpson grade 3–4; P<0.001) and WHO grade II–III (P<0.001), respectively (Supplementary Figure 4). Meningiomas with higher proliferative index (Ki-67 LI≥4) tended to show shorter recurrence-free survival compared with those with lower proliferative index (Ki-67 LI<4), although log-rank test did not reveal a statistical significance (P=0.079; Supplementary Figure 4).

The multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazard models revealed that genotype was independently associated with recurrent risk after adjustment for Simpson Grade, Ki-67 LI, and WHO grade (NF2 type vs TRAKLS type, HR=2.60 × 109, 95% CI=2.05 to infinity, P=0.008; Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

The application of next-generation sequencing as a routine laboratory examination is challenging owing to cost effectiveness. Numerous studies using next-generation sequencers have revealed clinically relevant genetic alterations in various tumors, and some researchers have recently advocated the clinical use of next-generation sequencers.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 This is the first study to establish a clinical sequencing system for meningioma, which is the most common brain tumor.

We investigated the genotype of 103 meningiomas by targeted amplicon sequencing, in which 79% (81/103) of cases carried at least one or more mutations in NF2, TRAF7, AKT1, KLF4, and SMO, and/or loss of NF2. These findings are compatible with a previous report in terms of proportion (79%, 237/300) and the unique pattern of gene alterations,8 thus helping to confirm the technical accuracy of our sequencing method. In terms of histological findings, we also confirmed the genotype-oriented histological pattern: all fibrous meningiomas were classified into NF2 type, and secretory component was associated with mutation in TRAF7 and KLF4; these trends were similar to previous reports.9, 21, 22 In addition, tumor size of NF2 type was larger than that of TRAKLS types, probably because of high proliferative ability. In fact, NF2 type meningioma showed higher Ki-67 LI compared with TRAKLS type, and this result is compatible with previous studies showing the relationship between NF2 and Ki-67 LI.23, 24 Meningiomas of NF2 type also showed characteristic findings in MRI such as calcification, adjacent bone change, and heterogeneous gadolinium enhancement, indicating that preoperative MRI findings including location and size, could be potential predictors for tumor genotype.

The recent establishment of an algorithm to analyze copy-number alterations by amplicon sequencing14 has expanded the application of targeted amplicon sequencing. Current, reliable, clinically practical methods to investigate copy-number alterations include I-FISH and quantitative PCR analysis; however, mutations cannot be simultaneously confirmed with these methods. The amplicon-sequencing system we employed in this study yielded valuable results of copy-number alterations in addition to mutations. Loss of NF2, which was found in 40–60% of sporadic meningioma,5, 6, 7, 10 was observed in 60% of our cases. I-FISH for NF2 was also performed in 35 out of 103 cases (34%) and the concordance rate between the results of I-FISH and next-generation sequencing was 79%. Four out of five cases with NF2 diploid by I-FISH but loss by next-generation sequencing carried protein-altering mutations in NF2. Almost all cases with mutations in NF2 have been shown to carry NF2 loss simultaneously.10, 11, 25, 26, 27, 28 Therefore, the result of I-FISH in these cases could be a false negative, suggesting the higher sensitivity and specificity of the amplicon-sequencing system for copy-number alterations. By contrast, one case showed monosomy 22 by I-FISH but did not show NF2 loss by next-generation sequencing, indicating the value of I-FISH as a laboratory examination for copy-number alterations.

NF2 inactivation is suggested to be an early event in sporadic meningioma pathogenesis,2, 29 but these gene alterations have been described to poorly correlate with prognosis. In fact, no significant difference in recurrence time was observed between patients with and without loss of 22q.30, 31 Conversely, the association between prognosis and mutations of TRAF7, AKT1, KLF4, and SMO, called the TRAKLS type in this study, have never been investigated. Here we revealed that genotype was associated with recurrence independently from the degree of surgical resection completeness (Simpson grade) and histological malignancy (Ki-67 LI and WHO grade), which is known as prognostic factors in meningioma.32, 33, 34 TRAKLS type was the most favorable genotype, so in addition to evaluating NF2 status, identifying this genotype from non-NF2 meningioma may help the accurate assessment of the recurrent risk. More recently, TERT promoter and PIK3CA mutations were reported to be associated with highly aggressive behavior or tumorigenesis in meningioma.35, 36, 37 The additional alteration of these genes might be responsible for the recurrence of meningioma or even for the tumorigenesis of NOC type, although additional investigations for these gene mutations in association with the genetic status of NF2, TRAF7, AKT1, KLF4, and SMO are needed. Genotypes obtained from the clinical sequencing system would be useful for postoperative management, such as determination of follow-up interval or early postoperative radiotherapy, which was previously reported to improve the prognosis of patients with meningioma.38, 39 The shorter turnaround time of our clinical sequencing system, within 7 days after surgery, will provide clinical benefit to patients in terms of seamless genotype-oriented treatment after surgery (Figure 3).

Clinically relevant actionable mutations have been found in various tumors, such as EGFR L858R in lung cancer,40 KRAS G12D in colorectal cancer,41 and BRAF V600E in melanoma.42 Patients with tumors carrying these actionable mutations have been treated effectively with appropriate medicines including molecular targeted therapy. In meningiomas, mutations in SMO and AKT1 may be predictive biomarkers of some molecular targeted drugs such as Hedgehog inhibitors and AKT inhibitors.43 Although patients with these gene mutations showed better prognosis, these tumors are frequently located in the skull base. When the tumor is difficult to completely resect because of its location, Hedgehog inhibitors or AKT inhibitors could be considered as a treatment agent. Therefore, establishing a clinical sequencing system is also crucial for providing personalized medicine.

Quality control of DNA is a crucial problem for the clinical sequencing system. We used PAXgene-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues owing to the high quality of DNA extracted from PAXgene-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens44, 45 and conserved histological morphology.46 In fact, we analyzed two cases of meningioma using genomic DNA extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue and obtained similar but imprecise results of copy-number alterations (data not shown), mostly because of DNA fragmentation by formalin fixation.47, 48, 49 For an appropriate clinical sequencing system, concomitance of conserved histology and high-quality nucleotide extraction must be achieved, therefore an alternative sample preparation method, other than snap-frozen or formalin fixation, such as the PAXgene Tissue System, would be considered. Application of our system to widely used formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue would require fine-tuning of some thresholds such as variant frequency for mutation analysis or score Q for copy-number alteration analysis.

In conclusion, we established a rapid clinical sequencing system for meningioma by targeted amplicon sequencing. The genotypes obtained by this system were significantly associated with clinicopathological features including histological subtypes, tumor size, MRI findings, and recurrence-free survival. The prevalence of such a clinical sequencing system will bring multiple benefits to meningioma patients by means of more accurate diagnosis and individualized medicine.

References

Claus EB, Bondy ML, Schildkraut JM et al. Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery 2005;57:1088–1095.

Mawrin C, Perry A . Pathological classification and molecular genetics of meningiomas. J Neurooncol 2010;99:379–391.

Ruiz J, Martinez A, Hernandez S et al. Clinicopathological variables, immunophenotype, chromosome 1p36 loss and tumour recurrence of 247 meningiomas grade I and II. Histol Histopathol 2010;25:341–349.

Adeberg S, Hartmann C, Welzel T et al. Long-term outcome after radiotherapy in patients with atypical and malignant meningiomas—clinical results in 85 patients treated in a single institution leading to optimized guidelines for early radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;83:859–864.

Ruttledge MH, Sarrazin J, Rangaratnam S et al. Evidence for the complete inactivation of the NF2 gene in the majority of sporadic meningiomas. Nat Genet 1994;6:180–184.

Seizinger BR, de la Monte S, Atkins L et al. Molecular genetic approach to human meningioma: loss of genes on chromosome 22. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987;84:5419–5423.

Zankl H, Zang KD . Cytological and cytogenetical studies on brain tumors. 4. Identification of the missing G chromosome in human meningiomas as no. 22 by fluorescence technique. Humangenetik 1972;14:167–169.

Clark VE, Erson-Omay EZ, Serin A et al. Genomic analysis of non-NF2 meningiomas reveals mutations in TRAF7, KLF4, AKT1, and SMO. Science 2013;339:1077–1080.

Kros J, de Greve K, van Tilborg A et al. NF2 status of meningiomas is associated with tumour localization and histology. J Pathol 2001;194:367–372.

Hansson CM, Buckley PG, Grigelioniene G et al. Comprehensive genetic and epigenetic analysis of sporadic meningioma for macro-mutations on 22q and micro-mutations within the NF2 locus. BMC Genomics 2007;8:16.

Tabernero M, Jara-Acevedo M, Nieto AB et al. Association between mutation of the NF2 gene and monosomy 22 in menopausal women with sporadic meningiomas. BMC Med Genet 2013;14:114.

Buccoliero AM, Castiglione F, RDI D et al. NF2 gene expression in sporadic meningiomas: relation to grades or histotypes real time-pCR study. Neuropathology 2007;27:36–42.

Perry A, Louis DN, Scheithauer BW et al. Meningiomas. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD et al. (eds). WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System, 4th edn. IARC: Lyon, France, 2007, pp 164–172.

Reinecke F, Satya RV, DiCarlo J . Quantitative analysis of differences in copy numbers using read depth obtained from PCR-enriched samples and controls. BMC Bioinformatics 2015;16:17.

Al-Rohil RN, Tarasen AJ, Carlson JA et al. Evaluation of 122 advanced-stage cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas by comprehensive genomic profiling opens the door for new routes to targeted therapies. Cancer 2016;122:249–257.

Coco S, Truini A, Vanni I et al. Next generation sequencing in non-small cell lung cancer: new avenues toward the personalized medicine. Curr Drug Targets 2015;16:47–59.

Johnson DB, Dahlman KH, Knol J et al. Enabling a genetically informed approach to cancer medicine: a retrospective evaluation of the impact of comprehensive tumor profiling using a targeted next-generation sequencing panel. Oncologist 2014;19:616–622.

Marrone M, Filipski KK, Gillanders EM et al. Multi-marker solid tumor panels using next-generation sequencing to direct molecularly targeted therapies. PLoS Curr 2014;6.

Roy-Chowdhuri S, de Melo Gagliato D, Routbort MJ et al. Multigene clinical mutational profiling of breast carcinoma using next-generation sequencing. Am J Clin Pathol 2015;144:713–721.

Sahm F, Schrimpf D, Jones DT et al. Next-generation sequencing in routine brain tumor diagnostics enables an integrated diagnosis and identifies actionable targets. Acta Neuropathol 2015, [Epub ahead of print].

Reuss DE, Piro RM, Jones DT et al. Secretory meningiomas are defined by combined KLF4 K409Q and TRAF7 mutations. Acta Neuropathol 2013;125:351–358.

Wellenreuther R, Kraus JA, Lenartz D et al. Analysis of the neurofibromatosis 2 gene reveals molecular variants of meningioma. Am J Pathol 1995;146:827–832.

Antinheimo J, Haapasalo H, Haltia M et al. Proliferation potential and histological features in neurofibromatosis 2-associated and sporadic meningiomas. J Neurosurg 1997;87:610–614.

Pavelin S, Becic K, Forempoher G et al. The significance of immunohistochemical expression of merlin, Ki-67, and p53 in meningiomas. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2014;22:46–49.

De Vitis LR, Tedde A, Vitelli F et al. Screening for mutations in the neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) gene in sporadic meningiomas. Hum Genet 1996;97:632–637.

Leone PE, Bello MJ, de Campos JM et al. NF2 gene mutations and allelic status of 1p, 14q and 22q in sporadic meningiomas. Oncogene 1999;18:2231–2239.

Ng HK, Lau KM, Tse JY et al. Combined molecular genetic studies of chromosome 22q and the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene in central nervous system tumors. Neurosurgery 1995;37:764–773.

Ueki K, Wen-Bin C, Narita Y et al. Tight association of loss of merlin expression with loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 22q in sporadic meningiomas. Cancer Res 1999;59:5995–5998.

Riemenschneider MJ, Perry A, Reifenberger G . Histological classification and molecular genetics of meningiomas. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:1045–1054.

Linsler S, Kraemer D, Driess C et al. Molecular biological determinations of meningioma progression and recurrence. PLoS One 2014;9:e94987.

Sulman EP, Dumanski JP, White PS et al. Identification of a consistent region of allelic loss on 1p32 in meningiomas: correlation with increased morbidity. Cancer Res 1998;58:3226–3230.

Oya S, Kawai K, Nakatomi H et al. Significance of Simpson grading system in modern meningioma surgery: integration of the grade with MIB-1 labeling index as a key to predict the recurrence of WHO Grade I meningiomas. J Neurosurg 2012;117:121–128.

Yamaguchi S, Terasaka S, Kobayashi H et al. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with high-grade meningioma and recurrence-risk stratification for application of radiotherapy. PLoS One 2014;9:e97108.

Abry E, Thomassen IO, Salvesen OO et al. The significance of Ki-67/MIB-1 labeling index in human meningiomas: a literature study. Pathol Res Pract 2010;206:810–815.

Goutagny S, Nault JC, Mallet M et al. High incidence of activating TERT promoter mutations in meningiomas undergoing malignant progression. Brain Pathol 2014;24:184–189.

Sahm F, Schrimpf D, Olar A et al. TERT promoter mutations and risk of recurrence in meningioma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;108.

Abedalthagafi M, Bi WL, Aizer AA et al. Oncogenic PI3K mutations are as common as AKT1 and SMO mutations in meningioma. Neuro Oncol 2016, [Epub ahead of print].

Aboukais R, Baroncini M, Zairi F et al. Early postoperative radiotherapy improves progression free survival in patients with grade 2 meningioma. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2013;155:1385–1390.

Kaur G, Sayegh ET, Larson A et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy for atypical and malignant meningiomas: a systematic review. Neuro Oncol 2014;16:628–636.

Han SW, Kim TY, Hwang PG et al. Predictive and prognostic impact of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2493–2501.

Plesec TP, Hunt JL . KRAS mutation testing in colorectal cancer. Adv Anat Pathol 2009;16:196–203.

Shepherd C, Puzanov I, Sosman JA . B-RAF inhibitors: an evolving role in the therapy of malignant melanoma. Curr Oncol Rep 2010;12:146–152.

Brastianos PK, Horowitz PM, Santagata S et al. Genomic sequencing of meningiomas identifies oncogenic SMO and AKT1 mutations. Nat Genet 2013;45:285–289.

Staff S, Kujala P, Karhu R et al. Preservation of nucleic acids and tissue morphology in paraffin-embedded clinical samples: comparison of five molecular fixatives. J Clin Pathol 2013;66:807–810.

Viertler C, Groelz D, Gundisch S et al. A new technology for stabilization of biomolecules in tissues for combined histological and molecular analyses. J Mol Diagn 2012;14:458–466.

Kap M, Smedts F, Oosterhuis W et al. Histological assessment of PAXgene tissue fixation and stabilization reagents. PLoS One 2011;6:e27704.

Howat WJ, Wilson BA . Tissue fixation and the effect of molecular fixatives on downstream staining procedures. Methods 2014;70:12–19.

Lehmann U, Kreipe H . Real-time PCR analysis of DNA and RNA extracted from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded biopsies. Methods 2001;25:409–418.

Nam SK, Im J, Kwak Y et al. Effects of fixation and storage of human tissue samples on nucleic acid preservation. Korean J Pathol 2014;48:36–42.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr Jun Moriya (Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine) for his technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Modern Pathology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yuzawa, S., Nishihara, H., Yamaguchi, S. et al. Clinical impact of targeted amplicon sequencing for meningioma as a practical clinical-sequencing system. Mod Pathol 29, 708–716 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.81

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.81

This article is cited by

-

Molekulare Biologie, Diagnostik und Therapie von Meningeomen

Der Pathologe (2019)

-

Selective vulnerability of the primitive meningeal layer to prenatal Smo activation for skull base meningothelial meningioma formation

Oncogene (2018)

-

Advances in meningioma genetics: novel therapeutic opportunities

Nature Reviews Neurology (2018)

-

Genetic landscape of meningioma

Brain Tumor Pathology (2016)