Abstract

In recent years it has become clear that many extra-uterine (pelvic) high-grade serous carcinomas (serous carcinomas) are preceded by a precursor lesion in the distal fallopian tube. Precursors range from small self-limited ‘p53 signatures’ to expansile serous tubal intraepithelial neoplasms that include both serous tubal epithelial proliferations (or lesions) of uncertain significance and serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas. These precursors can be considered from three perspectives. The first is biologic underpinnings, which are multifactorial, and include the intersection of DNA damage with Tp53 mutations and disturbances in transcriptional regulation that increase with age. The second perspective is the morphologic discovery and classification of intraepithelial neoplasms that are intercepted early in their natural history, either incidentally or in risk-reduction surgeries for germline mutations. For the practicing pathologist, as well as the investigators, a distinction between a primary intraepithelial neoplasm and an intramucosal carcinoma must be made to avoid misinterpreting (or underestimating) the significance of these proliferations. The third perspective is the application of this information to intervention, devising strategies that will actually lower the ovarian cancer death rate by opportunistic salpingectomy, widespread comprehensive genetic screening and early detection. Central to this issue are the questions of (1) whether some STICs are metastatic, (2) whether lower-grade epithelial proliferations can invade prior to evolving into intraepithelial carcinoma, or (3) metastasize and become malignant elsewhere (‘precursor escape’). An important caveat is the persistent and unsettling reality that many high-grade serous carcinomas are not associated with an obvious point of initiation in the fallopian tube. The pathologist sits squarely in the midst of all of these issues, and has a pivotal role in managing expectations for stemming the death rate from this lethal disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The past two decades have witnessed a revolution in the field of ovarian cancer research. It began with the discovery of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumor suppressor genes, followed by the emergence of the fallopian tube as a potential source of at least some serous carcinomas and culminating in a body of evidence that has identified the fallopian tube as a major participant in the pathogenesis of this lethal disease.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 As with many paradigm shifts, much of the data in support of this change in attention from ovary to fallopian tube was rooted in histo-pathologic study. Painstaking analysis of ovaries and fallopian tubes of healthy women undergoing risk-reduction bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA+) has led to the identification of epithelial atypias or early carcinomas in the fallopian tube. The introduction of the SEE-FIM protocol for routine fallopian tube analysis in 2005 was followed by a widespread appreciation of early serous cancer of the tubes, both in BRCA+ women and those with no known genetic predisposition.8 A serous carcinogenic sequence in the fallopian tubes, alluded to early on by Zweemer and colleagues, was described further, crystalizing the concept of a tubal origin.2, 4, 9, 10 The particularly high likelihood of discovering an early high-grade serous carcinoma in the fallopian tubes rather than elsewhere in the pelvis has raised the possibility that a significant percentage of these tumors start in the oviduct.11, 12 This has fueled hopes that opportunistic salpingectomy will not only benefit the general population but also be a viable alternative to salpingo-oophorectomy for BRCA+ women seeking protection from serous carcinoma while retaining their ovarian function.13 These hopes are countered by the vagaries inherent in assumptions made based on seemingly obvious data, unanswered questions and paradoxes that must be resolved by further investigation.

This revolution in our understanding of ovarian cancer—and the questions that remain—can be viewed from three perspectives that inform future strategies of management and prevention. The first is the intersection of a series of biologic events that give rise to cancer risk in the fallopian tube, which highlights the profound need to understand the sequence of events involved in tubal carcinogenesis. The second is the interception of serous carcinoma by examination of the tube, which addresses the detection, its etiologic significance, proper classification, and ascertainment of outcome risk. The third is intervention, which draws from the existing knowledge base and pertains to the promise of prophylactic salpingectomy and potential pitfalls. In this review, we summarize each of these three perspectives with attention to what has been accomplished and what remains to be clarified.

In this review we accept the fact that the level of certainty regarding the origin of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma is governed by certain variables. The likelihood that the lesion arose in the tube is greatest when (1) a spectrum of atypia from low to high grade is present, (2) the lesion is unilateral, and (3) advanced disease is absent, as seen in risk reducing salpingo-oophorectomies for women with germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. In contrast, the likelihood that the intraepithelial carcinoma arose from the tube is less when (1) a spectrum of atypia is absent—that is, the intraepithelial neoplasm is composed exclusively of cells with marked atypia -, (2) the neoplasm is seen in both fallopian tubes, and (3) advanced disease (including endosalpingeal tumor) is present, the possibility that one or both tubal intraepithelial neoplasms is a metastasis must be considered. The purpose of making these distinctions is to foster a critical estimate of the potential origin for each intramucosal carcinoma in the fallopian tube.

Intersection

Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas have been recognized in the fallopian tube for decades but the link between these lesions and ovarian carcinomas in general has gone undeveloped until recently.14 Several observations have clarified this relationship, some of which are summarized in Table 1. A series of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas is illustrated in Figures 1a–d.

Examples of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. Note the conspicuous loss of normal epithelial maturation, with loss of polarity. Arrows denote irregular nuclear stacking (a–d), small detached papillary clusters (a), horizontally oriented surface nuclei (d), and intraepithelial fractures (a, c, and d).

BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation-Associated Atypia

The presence of epithelial atypia was appreciated in fallopian tubes of women with BRCA mutations (BRCA+). The discovery of the BRCA genes accelerated programs targeting the ovaries and fallopian tubes with the onset of the risk reducing salpingo-oophorectomy.1 Beginning in 2000, several groups noted the potential role of the fallopian tube in the genesis of serous carcinoma in BRCA+ women.2, 3, 4, 6 These studies identified serous tubal intraepithelial neoplasms in women at risk and in some cases linked them genetically to serous carcinomas.

The Distal Fallopian Tube

There was a predilection for serous carcinomas (in the form of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas) to emerge from the distal fallopian tube. Cass et al noted in 2005 that the majority of tubal cancers arose from the distal or fimbriated end.5 In January 2005, Brigham and Women's Hospital initiated the SEE-FIM protocol for the evaluation of women at genetic (BRCA+) or historical risk (strong family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer) for serous carcinoma. As a result of this protocol, it was possible to corroborate the observation that most early tubal malignancies arose in the fimbria or distal one-third of the oviduct.8

Association with Advanced Serous Carcinoma

The frequency of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma is high in women with symptomatic serous carcinoma. To determine whether serous carcinomas in general had a high frequency of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma, Kindelberger et al applied the SEE-FIM protocol to a consecutive series of women with high-grade serous carcinoma.15 They found that ~45% had a coexisting STIC. The precise percentage was somewhat difficult to ascertain given the fact that the distal tube was frequently obliterated or not amenable to thorough examination. Subsequent estimates have linked STICs to high-grade serous carinomas in from <20 to 60 percent.16 This broad figure contrasted with the frequency of STIC detection when high-grade serous carcinomas were detected incidentally or early. In BRCA+ women undergoing risk-reduction surgery, early high-grade serous carcinomas were discovered on examination of the tubes and ovaries in from 5 to 10%. Approximately 80–100% of these early high-grade serous carcinomas were associated with involvement of the fallopian tube in the form of a serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma.11, 17, 18 To reduce the likelihood that intraepithelial carcinoma was a product of metastatic spread, Kindelberger et al required that it be separated from the invasive component and conform to a pattern in keeping with an intraepithelial carcinoma.

A Morphologic Spectrum of Precursor Disease

Serous cancer precursors in the tube comprise a morphologic spectrum. The least atypical are small stretches of nearly normal appearing, mostly non-ciliated cells with evidence of Tp53 mutations called p53 signatures (Figure 2a).9 p53 signatures are encountered in ~50% of fallopian tubes of women irrespective of their level of genetic risk and are presumed to be emblematic of the early events on the pathway to serous carcinoma. Much less common are atypical serous tubal epithelial proliferations that are more conspicuous histologically and usually more extensive (Figures 2b–d).17, 19, 20 The morphologic point at which a p53 signature transitions to such a intraepithelial lesion is somewhat arbitrary and is governed chiefly by the appreciation of more conspicuous cytologic changes, including not only loss of cilia but greater epithelial pseudo-stratification, often with some nuclear enlargement.9, 10

(a) p53 signature (lower) with inconspicuous atypia and strong p53 staining (inset). (b) Serous tubal epithelial proliferation (lesion) of uncertain significance, exhibiting multilayered cohesive epithelium with preserved polarity. We would not classify this as a serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma but the reader is advised that there is considerable inter-observer variability in interpretation of such proliferations. (c) Serous tubal intraepithelial proliferation (right) merges with a serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (left, arrows). (d) Serous tubal intraepithelial proliferation (left) with adjacent invasive carcinoma (right). Note there is no intervening tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. Immunostains and the epithelium in question at greater magnification (center) are in the insets.

Microenvironment of the Distal Fallopian Tube

It is important to stress that small foci of Tp53 mutations (p53 signatures), whereas occurring in a high percentage of tubes, are not abundant in a given tube, indicating that loss of p53 function is an uncommon event over the lifetime of a given individual. Precisely where the genotoxic insult leading to loss of p53 function comes from is not entirely clear. One possibility is oxidants in follicular fluid post ovulation, which might explain why fimbrial mucosa, which is identical biologically to that in the more proximal tube but closer to the ovarian surface, is more susceptible.21, 22 Logically, the cells most vulnerable to transformation are those less mature, so-called secretory (or non-ciliated) cells. These have also been shown to be most vulnerable to DNA damage in vitro.23

Another variable that may be geographically unique is so-called ‘epigenetic reprogramming,’ alterations in the methylome unique to the distal fallopian tube. This has been proposed recently and is another argument for the unique susceptibility of the distal tube to serous carcinoma.24

Why is the BRCA+ fallopian tube susceptible to malignancy? The simplest explanation is that the combined functional loss of p53 and BRCA (or related pathway) is a fundamental driving force in the genesis of high-grade serous carcinoma.25 Given that the tubal cells in the woman with germline BRCA1/2 loss contain only one functional allele, they may be particularly vulnerable to loss of BRCA function via genotoxic stress, which must be substantial in a particular cell to inactivate the entire p53 locus. Although loss of both BRCA alleles should lead to cell death if p53 is intact, the more likely scenario is loss of p53 function (relatively common) followed by a second insult inactivating the BRCA locus.

What if the patient is uniquely prone to loss of p53 function? Such a scenario can be witnessed in the fallopian tubes of women with Li Fraumeni syndrome. In this unique population, the fallopian tubes contain abundant p53 signatures, most manifesting as very short stretches of p53-positive cells.26 The simplest explanation for these prevalent foci of p53 staining is that a single functioning allele is more easily inactivated, requiring less genotoxic damage. Why these individuals do not have an elevated risk for serous carcinoma is not clear, but conceivably the events that lead to loss of the second p53 allele are not sufficient to inactivate both BRCA alleles in these patients. Still, STICs have rarely been encountered in tubes from these individuals (Carinelli, personal written communication).

Ultimately p53 mutations link signatures to both intraepithelial neoplasms of the tube and serous carcinomas. Shared p53 mutations have been shown in these precursors and adjacent neoplasms.9, 15, 27 Other abnormalities have also been documented including altered telomeres.28, 29

It is possible to envision that the probability of small genotoxic insults—leading to p53 signatures—is high, whereas insults must either be severe or repetitive to lead to a significant loss of function with immediate neoplastic growth. Still both likely occur, leading to a range of atypias in the tubes with different transit times to malignancy and metastasis. It should be emphasized that the genotoxic stimulus may not be the same in all individuals. We have occasionally seen multiple precursors in the fallopian tubes of some women with early serous carcinoma, raising the possibility that certain fallopian tubes are exposed to more severe genotoxic insults.

Generic Stem Cell Vulnerability

There are other molecular events taking place in the tubal mucosa that appear independent of the process of cell exposure to reactive oxygen species. These proliferations are neither linked to p53 mutations nor confined to the distal fallopian tube but may emerge from the same cell as serous cancer precursors.30 We have termed these proliferations secretory or stem cell outgrowths (SCOUTs). They share some attributes with serous cancer precursors.31, 32 Type I SCOUTs, have conspicuous ciliated differentiation (Figure 3a). Type II SCOUTs are distinctly endometrioid in appearance, limited ciliated cells and a more pseudostratified growth pattern and evidence of disturbances in expression in the Wnt pathway (Figures 3b and c). SCOUTs appear to be more common after menopause and are increased in women with serous carcinoma although not directly related.33 Another study examining a similar entity in the fallopian tube termed secretory cell expansions (SCEs) found a similar association with serous carcinoma.34 A number of studies have focused on the role of stem cells in this process and why this population is particularly vulnerable.35

Stem cell outgrowths in the fallopian tube. (a) A type I stem cell outgrowth (right of dotted line) demonstrates a discrete pattern of ciliated differentiation. (b) A type II stem cell outgrowth has a distinctly endometrioid appearance. (c) A secretory cell expansion is similar and consists of a discrete linear population of secretory cells, highlighted here by immunostaining for BCL-2.

Interception

This segment addresses three issues of particular interest to the practitioner, including (1) protocols for detecting serous tubal intraepithelial neoplasms and their realistic expectations, (2) Terminology for this spectrum and criteria for diagnosis, and (3) Reporting these findings in a manner that will facilitate management.

Detection

The SEE-FIM protocol was designed to provide for a systematic examination of the distal fallopian tube in women undergoing risk-reduction surgery for BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations (BRCA+). At least 70% of tubal cancers arise in the fimbriated portion, and nearly all will be found in the distal one-third of the tube. The SEE-FIM protocol entails multiple sagittal sections of the distal tube to increase the surface area examined, combined with 2 mm-thick sections of the remainder. This detailed sectioning protocol is necessary to maximize the detection of early cancers in women at risk.8 We also employ this protocol in all cases of uterine or ovarian cancer where the tubes can be identified, and this approach has identified early tubal carcinomas in women with both serous and endometrioid tumors in the uterus.36, 37, 38

Terminology and Its Implications

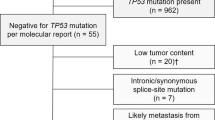

The term serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma has been used in practice but there are several issues that remain in flux for both the practitioner and investigator. (1) The malignant potential (ie risk of serous cancer outcome) of incidentally discovered intraepithelial carcinoma is at this writing low, estimated a ~5% in BRCA+ women. (2) A series of incidentally discovered intraepithelial carcinomas and subsequent serous cancers have yet to be linked by a common mutation in Tp53 to prove a temporal link between the two. (3) The malignant potential of tubal atypias falling short of intraepithelial carcinoma remains uncertain.39 (4) Some serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas discovered in the context of metastatic disease may not necessarily have originated from the fallopian tube. A tubal intraepithelial carcinoma found associated with serous carcinoma might be viewed as a fait accompli, assumed to be the origin of the tumor based simply on a shared mutation with the latter.14, 24 However, a similar sharing of mutations can be seen between serous carcinomas in the endometrium and tube, yet the direction of spread (from the tube or to the tube) is not entirely clear.36, 40 Moreover, the possibility that the tubal mucosa can be not only a source but also a destination of serous carcinoma is being increasingly recognized.41 Thus when a diagnosis of intraepithelial carcinoma is made, the practitioner should view it in the context of whether the tubal lesion is isolated or a component of widespread disease.

Several terms have been proposed to classify lesions that fall between p53 signatures and tubal intraepithelial carcinomas, including tubal intraepithelial lesions in transition, serous tubal intraepithelial lesions and tubal epithelial atypias. We asked a group of experienced gynecologic oncologists to advise us on their preference for terminologies in a report (see 'Acknowledgments' section). Diagnoses such as serous tubal epithelial proliferation or serous tubal intraepithelial lesion were considered suitable to many but the addition of ‘of uncertain significance’ was preferred by many as it clarified the uncertainty of this diagnosis (see Table 2).

There are four reasons for including both serous tubal epithelial proliferations (or lesions) of uncertain significance and serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas within the category of tubal intraepithelial neoplasia, at least for the purposes of study and follow-up.

-

1)

Both are often found in continuity (Figure 2c).

-

2)

Both share a similar age distribution and association with germline BRCA mutations

-

3)

The two cannot always be distinguished with certainty.37, 39, 42

-

4)

In our experience serous tubal epithelial proliferations can be found adjacent to invasive serous carcinoma without an intervening intraepithelial carcinoma (Figure 2d), implying that invasion might occur directly from the lesion.

-

5)

There is the possibility that tubal epithelial proliferations could initiate a sequence of biologic events culminating in a serous carcinoma outside of the fallopian tube. This process, which we term precursor escape, would entail an initial genotoxic insult in the fallopian tube leading to a p53 signature or intraepithelial lesion, the cells of which could escape and emerge later in the pelvis as a more advanced neoplasm. This concept is under investigation.

The Risk-Reduction Salpingo-Oophorectomy

From 5–10% of BRCA+ women undergoing risk-reduction surgery will harbor an asymptomatic early serous neoplasm, and at least 80% of those neoplasms will be an intraepithelial carcinoma with either early invasion or spread to adjacent peritoneal surfaces.6, 8, 17 In this population, many will be found to have intraepithelial carcinoma alone. It is important to emphasize that women who undergo risk-reduction surgery for a history of breast or ovarian cancer who do not have germline BRCA mutation seem to have a very low risk of intraepithelial carcinoma, approaching that of the general population.

The Symptomatic Woman with Uterine or Pelvic Epithelial Cancer

Approximately 40–60 percent of women with an extra-uterine serous carcinoma will harbor an intraepithelial carcinoma in the fallopian tube.15, 16 The precise percentage varies considerably, and it is impossible to obtain accurate information because (1) in many cases the fallopian tube is obscured by a tumor mass, (2) the tumor might overrun an intraepithelial carcinoma, and (3) a tumor could arise on the ovary within adhesions or endosalpingiosis ultimately derived from the fallopian tube. (4) It is also possible that a lesion might be missed that was present on deeper levels.43 However, in a study employing exhaustive serial sectioning, we found a serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma in only 2 of 35 fallopian tubes initially ruled negative from women with serous carcinoma. What is obvious is that identifying a clear-cut origin in the ovary for serous carcinoma is more difficult than in the fallopian tube. Some feel strongly that serous carcinomas can arise from the ovarian surface epithelium, defined as a specialized mesothelial covering.44, 45 Another, more visibly tangible argument is that serous carcinomas arise from endometriosis, endosalpingiosis or a similar nidus of ectopic mullerian epithelium (secondary Mullerian system) in the ovarian cortex.46, 47 However, such associations, including reports of serous carcinomas arising in benign or borderline cystadenomas, are uncommon.48, 49 It should be noted however, that precursor lesions with Tp53 mutations are rarely found in the ovarian cortex despite some earlier reports.50, 51, 52 Moreover, Bell and Scully reported only 13 cases of ‘early’ serous carcinoma in their review of a large consultation practice.53

The Woman who is not at Risk and Undergoing Routine Salpingo-Oophorectomy

There is little information on the likelihood of encountering a serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma in a routine specimen. One study noted a frequency of ~1 in 150.54 In an analysis of cases seen at Brigham and Women’s hospital over the 10-year period 2006–2015, the overall frequency of encountering intraepithelial carcinoma in any tubal specimen associated with anything other than a serous carcinoma of the ovary or endometrium was ~1 in every 500 cases; however, these included incidental cases discovered in women with endometrioid adenocarcinomas as discussed above.35

Histologic Criteria for Serous Tubal Intraepithelial Carcinoma

The histologic criteria for intraepithelial carcinoma are on one hand empiric, ie, they are dictated by prior experience in the uterus (with serous endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma).55 On the other hand, they are corroborated to some degree by several biomarkers that correlate with serous cancer, most notably, p53, p16, Stathmin, Cyclin E, Ki-67, and others.9, 19, 56 However, a lack of precision in terms of both information on natural history and biomarker specificity hamper efforts to achieve a perfect separation of proliferations of unknown significance from intraepithelial carcinomas.

-

1)

The entire spectrum from p53 signature to intraepithelial carcinoma exhibits altered p53 expression.

-

2)

Biomarkers positive in intraepithelial carcinomas might also be positive in earlier precursors. STMN1 is sometimes up-regulated in some SCOUTs.31 Proliferation (MIB1) indices between serous tubal epithelial proliferations and intraepithelial carcinomas overlap. Cyclin E and p16 are up-regulated in intraepithelial carcinomas but not always.26 It is fair to say that: (a) pathologists cannot consistently separate an intraepithelial lesion from an intraepithelial carcinoma with biomarkers, (b) most of these lesions, whether they be intraepithelial proliferations of uncertain significance or intraepithelial carcinomas, will not be followed by a pelvic serous carcinoma.

The proliferative index is increased relative to the normal mucosa. Some have given an overall proliferative index of >10% to be frequently associated with intraepithelial carcinoma.39 Another approach has been to record proliferative index based on the maximum proliferative index in a given portion of the lesion.10 The purpose for doing this is the assumption that the most proliferative region carries the most biologic significance. However, this is unproven and irrespective of the approach used, a specific cutoff value does not exist as a stand-alone parameter to distinguish intraepithelial lesion from intraepithelial carcinoma. Strong staining with both stathmin 1 and p16 supports a diagnosis of STIC in the context of the above findings and may be helpful, but such staining patterns can be found in lower grade lesions.31 Additional markers that have been proposed include Rsf-1, LAMC1, and fatty acid synthase.57, 58

Examples of intraepithelial carcinomas are shown in Figures 1a–d and we pay attention to the following:

-

1)

Epithelial thickness: The epithelium is virtually always multilayered although the thickness can be highly variable.

-

2)

Loss of normal cell to cell orientation (polarity): in a pure non-ciliated population of neoplastic cells, loss of polarity may take the form of small micro-papillae (Figures 1a and d, arrows) and un-oriented stratified cells with stacking of rounded nuclei in contrast to a more uniform interdigitated population of elongated nuclei (Figure 1b, arrows). This is in contrast to lesser proliferations (Figure 2c). Small clusters of cells near the epithelial surface may become separate from the group and in some instances a pronounced horizontal intraepithelial fracture is present (Figure 1d, arrows).59

In normal epithelium, ciliated differentiation can occur throughout the epithelium and can be associated with epithelial stratification and multi-layering, features that in a pure non-ciliated epithelium might be a cause for concern (Figures 4a and b). Uncommonly, intraepithelial lesions with loss of Tp53 function will still manifest with ciliated differentiation, creating some difficulty in determine whether polarity is disrupted (Figure 4c). In general, cilia should be scarce in intraepithelial carcinomas because they signify differentiation. When encountered they must be carefully evaluated and their presence weighed against the other findings when considering a diagnosis of intraepithelial carcinoma. Ciliated cells will not stain for p53, however ciliated differentiation is sometimes seen in lower grade lesions. Because a lower grade lesion could immediately precede an invasive carcinoma (Figure 3d, arrows), careful sectioning is needed to ensure that invasion has not occurred.

Potential difficulties in interpreting polarity in the context of multilayered epithelium. (a) Benign epithelium is multilayered but terminates in a smooth luminal border with ciliated differentiation (arrows). (b) An adjacent serous epithelial proliferation (or lesion) of uncertain significance with mild atypia and multilayered epithelium. This was positive for abnormal p53 expression. Note the presence of some nuclear enlargement and nucleoli and a mitotic figure (long arrow); however, the luminal surface is uniform with normal differentiation (cilia; arrows). (c) Another multilayered tubal epithelium with strong p53 staining and moderate MIB1 staining (insets). Note however, the abundant cilia on the hematoxylin and eosin stained section, corresponding to the absence of p53 immunostaining in the inset. We would classify this as a serous tubal epithelial proliferation (or lesion) of uncertain significance, with a comment that it does not fulfill the criteria for an intraepithelial carcinoma. Cases like this underscore the range and complexity of serous cancer precursors that can be encountered in the fallopian tube and the care that must be taken in classifying problematic proliferations.

Management

Once the pathologist has identified a tubal intraepithelial neoplasm, he or she must render a diagnosis and provide information helpful to the clinician. Table 2 provides a variety of terminologies that might be used in practice. A diagnosis of tubal intraepithelial carcinoma need not be accompanied by an estimate of recurrence risk but referral to a gynecologic oncologist is encouraged. A diagnosis of a tubal proliferation of undetermined significance should come with an assessment of the level of atypia and why it is not being classified as an intraepithelial carcinoma. If there is uncertainty as to the classification this should be conveyed as well.

One issue that remains unclear is the staging of serous carcinomas, specifically the role of the fallopian tube. Currently staging is done with the tube in mind but does not rely on defining the source, an approach the authors support.60 Others have made an effort to assign probable origin based on pathologic parameters and estimate likelihood that the carcinomas originated in the fallopian tube based on an algorithm. The relevance of this algorithm to management remains unclear at this point.61

The differential diagnosis of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma includes a range of proliferations (Figure 5). These are discussed in detail in a number of publications. An important feature distinguishing most is the presence of normal immunostaining for p53, which largely excludes a serous cancer precursor.19, 32, 52

A decision tree for unusual tubal intraepithelial proliferations. *Altered epithelium is defined simply as epithelium that contrasts with the background tubal epithelium, such as discrete multilayered epithelium, monomorphic single and multilayered populations, or stretches of epithelium with loss of cilia etc. **Nuclear changes pertain to nuclear enlargement, nuclear molding, nuclear crowding etc. Note that given the morphologic ‘plasticity’ of the tubal epithelium, contrasting nuclear changes may still not by themselves signify a precursor or early serous carcinoma.

Intervention

In the past 15 years pathologists have had a critical role in driving the shift in our understanding of the origins of serous carcinoma, mostly through the painstaking analysis of pathologic specimens and progressive attention paid to the distal fallopian tube. With the close attention to the distal fallopian tube in routine practice the pathologist creates the opportunity to intercept early serous carcinomas. The ultimate significance of this discovery for the individual patient is unclear, but when intraepithelial carcinomas are discovered, it is reasonable to assume that some of these individuals will harbor germline BRCA mutations. Thus, testing should be offered to these patients, and the chance discovery of a STIC could therefore benefit additional persons in the family of the affected patient. The more widespread benefit of these discoveries pertains to the use of ‘opportunistic’ salpingectomy, the removal of the fallopian tubes in women who are undergoing surgery for benign disorders.12 Estimates based on retrospective studies project that the risk of ovarian cancer would be reduced by ~50% in those who have had their tubes removed.62 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and Society of Gynecologic Oncologists as well as many international groups have now issued policy statements encouraging physicians to have a dialog with their patients about undergoing this procedure during routine surgery with the expectation that it will reduce their risk of serous carcinoma.63, 64 This approach has received more urgent attention as serologic screening programs have been deemed to be of no real value.65 Additional studies are being planned that extend opportunistic salpingectomy to the BRCA+ population as a temporary measure to reduce risk while allowing for normal ovarian function for a period of time.66 At this point this approach would only be offered to BRCA+ women who have refused oophorectomy despite counseling due to its undesirable side effects. It is supported by the fact that a very high percentage of early high-grade serous carcinomas are found in the fallopian tube(s).11, 12 The pervasive caveat is the fact that many advanced serous carcinomas do not have a coexisting intraepithelial carcinoma.67 Other caveats, including the possibility that not all intraepithelial carcinomas are primary lesions, are listed in Table 1. This does not mean that salpingectomy will not be effective, but it does underscore the need to continually re-evaluate serous carcinomas from multiple perspectives, to identify subsets with different categories and to firmly establish their natural history and to determine if more than one pathway is involved.68, 69 Regardless, the progress achieved in this field in identifying site of origin in the past 20 years since the discovery of the BRCA genes has been transformative and will hopefully result in a significant reduction in the death rate from this disease.

References

Welcsh PL, King MC . BRCA1 and BRCA2 and the genetics of breast and ovarian cancer. Hum Mol Genet 2001;10:705–713.

Zweemer RP, van Diest PJ, Verheijen RH et al, Molecular evidence linking primary cancer of the fallopian tube to BRCA1 germline mutations. Gynecol Oncol 2000;76:45–50.

Paley PJ, Swisher EM, Garcia RL et al, Occult cancer of the fallopian tube in BRCA-1 germline mutation carriers at prophylactic oophorectomy: a case for recommending hysterectomy at surgical prophylaxis. Gynecol Oncol 2001;80:176–180.

Piek JM, van Diest PJ, Zweemer RP et al, Dysplastic changes in prophylactically removed Fallopian tubes of women predisposed to developing ovarian cancer. J Pathol 2001;195:451–456.

Cass I, Holschneider C, Datta N et al, BRCA-mutation-associated fallopian tube carcinoma: a distinct clinical phenotype? Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:1327–1334.

Colgan TJ, Murphy J, Cole DE et al, Occult carcinoma in prophylactic oophorectomy specimens: prevalence and association with BRCA germline mutation status. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1283–1289.

Carcangiu ML, Peissel B, Pasini B et al, Incidental carcinomas in prophylactic specimens in BRCA1 and BRCA2 germ-line mutation carriers, with emphasis on fallopian tube lesions: report of 6 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:1222–1230.

Medeiros F, Muto MG, Lee Y et al, The tubal fimbria is a preferred site for early adenocarcinoma in women with familial ovarian cancer syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:230–236.

Lee Y, Miron A, Drapkin R et al. A candidate precursor to serous carcinoma that originates in the distal fallopian tube [published erratum appears in: J Pathol 2007; 213:116]. J Pathol 2007;211:26–35.

Jarboe E, Folkins A, Nucci MR et al, Serous carcinogenesis in the fallopian tube: a descriptive classification. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2008;27:1–9.

Gilks CB, Irving J, Köbel M et al, Incidental nonuterine high-grade serous carcinomas arise in the fallopian tube in most cases: further evidence for the tubal origin of high-grade serous carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:357–364.

Morrison JC, Blanco LZ Jr, Vang R, Ronnett BM . Incidental serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and early invasive serous carcinoma in the nonprophylactic setting: analysis of a case series. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:442–453.

McAlpine JN, Hanley GE, Woo MM et al, Ovarian Cancer Research Program of British Columbia. Opportunistic salpingectomy: uptake, risks, and complications of a regional initiative for ovarian cancer prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210:471.e1–e11.

Pauerstein CJ, Woodruff JD . Cellular patterns in proliferative and anaplastic disease of the Fallopian tube. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1966;96:486–492.

Kindelberger DW, Lee Y, Miron A et al, Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: Evidence for a causal relationship. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:161–169.

Przybycin CG, Kurman RJ, Ronnett BM, Shih IeM, Vang R . Are all pelvic (nonuterine) serous carcinomas of tubal origin? Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:1407–1416.

Gilbert L, Basso O, Sampalis J et al, Assessment of symptomatic women for early diagnosis of ovarian cancer: results from the prospective DOvE pilot project. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:285–291.

Conner JR, Meserve E, Pizer E et al, Outcome of unexpected adnexal neoplasia discovered during risk reduction salpingo-oophorectomy in women with germ-line BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Gynecol Oncol 2014;132:280–286.

Vang R, Shih IeM, Kurman RJ . Fallopian tube precursors of ovarian low- and high-grade serous neoplasms. Histopathology 2013;62:44–58.

Powell CB, Chen LM, McLennan J et al, Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) in BRCA mutation carriers: experience with a consecutive series of 111 patients using a standardized surgical-pathological protocol. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2011;21:846–851.

Bahar-Shany K, Brand H, Sapoznik S et al, Exposure of fallopian tube epithelium to follicular fluid mimics carcinogenic changes in precursor lesions of serous papillary carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2014;132:322–327.

George SH, Milea A, Shaw PA . Proliferation in the normal FTE is a hallmark of the follicular phase, not BRCA mutation status. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:6199–6207.

Perets R, Wyant GA, Muto KW et al, Transformation of the fallopian tube secretory epithelium leads to high-grade serous ovarian cancer in Brca;Tp53;Pten models. Cancer Cell 2013;24:751–765.

Bartlett TE, Chindera K, McDermott J et al, Epigenetic reprogramming of fallopian tube fimbriae in BRCA mutation carriers defines early ovarian cancer evolution. Nat Commun 2016;7:11620.

Norquist BM, Garcia RL, Allison KH et al, The molecular pathogenesis of hereditary ovarian carcinoma: alterations in the tubal epithelium of women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Cancer 2010;116:5261–5271.

Xian W, Miron A, Roh M et al, The Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS): a model for the initiation of p53 signatures in the distal Fallopian tube. J Pathol 2010;220:17–23.

Kuhn E, Kurman RJ, Vang R et al, TP53 mutations in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and concurrent pelvic high-grade serous carcinoma—evidence supporting the clonal relationship of the two lesions. J Pathol 2012;226:421–426.

Salvador S, Rempel A, Soslow RA et al, Chromosomal instability in fallopian tube precursor lesions of serous carcinoma and frequent monoclonality of synchronous ovarian and fallopian tube mucosal serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2008;110:408–417.

Kuhn E, Meeker A, Wang TL et al, Shortened telomeres in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: an early event in ovarian high-grade serous carcinogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:829–836.

Yamamoto Y, Ning G, Howitt BE et al, In vitro and in vivo correlates of physiological and neoplastic human Fallopian tube stem cells. J Pathol 2016;238:519–530.

Chen EY, Mehra K, Mehrad M et al, Secretory cell outgrowth, PAX2 and serous carcinogenesis in the Fallopian tube. J Pathol 2010;222:110–116.

Ning G, Bijron JG, Yamamoto Y et al, The PAX2-null immunophenotype defines multiple lineages with common expression signatures in benign and neoplastic oviductal epithelium. J Pathol 2014;234:478–487.

Quick CM, Ning G, Bijron J et al, PAX2-null secretory cell outgrowths in the oviduct and their relationship to pelvic serous cancer. Mod Pathol 2012;25:449–455.

Li J, Ning Y, Abushahin N et al, Secretory cell expansion with aging: risk for pelvic serous carcinogenesis. Gynecol Oncol 2013;131:555–560.

Snegovskikh V, Mutlu L, Massasa E, Taylor HS . Identification of putative fallopian tube stem cells. Reprod Sci 2014;21:1460–1464.

Seidman JD, Krishnan J, Yemelyanova A, Vang R . Incidental serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and non-neoplastic conditions of the fallopian tubes in grossly normal adnexa: a clinicopathologic study of 388 completely embedded cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2016;35:423–429.

Meserve E, Mirkovic J, Conner J et al, Detection of Serous Tubal Intraepithelial Carcinoma (STIC) in Incidentally removed fallopian tubes from low-risk women. Lab Invest 2016; 297A.

McDaniel AS, Stall JN, Hovelson DH et al, Next-generation sequencing of tubal intraepithelial carcinomas. JAMA Oncol 2015;1:1128–1132.

Vang R, Visvanathan K, Gross A et al, Validation of an algorithm for the diagnosis of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2012;31:243–253.

Jarboe EA, Miron A, Carlson JW et al, Coexisting intraepithelial serous carcinomas of the endometrium and fallopian tube: frequency and potential significance. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2009;28:308–315.

Rabban JT, Vohra P, Zaloudek CJ . Nongynecologic metastases to fallopian tube mucosa: a potential mimic of tubal high-grade serous carcinoma and benign tubal mucinous metaplasia or nonmucinous hyperplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:35–51.

Carlson JW, Jarboe EA, Kindelberger D et al, Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: diagnostic reproducibility and its implications. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2010;29:310–314.

Rabban JT, Krasik E, Chen LM, Powell CB et al, Multistep level sections to detect occult fallopian tube carcinoma in risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomies from women with BRCA mutations: implications for defining an optimal specimen dissection protocol. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1878–1885.

Deligdisch L, Gil J, Kerner H et al, Ovarian dysplasia in prophylactic oophorectomy specimens: cytogenetic and morphometric correlations. Cancer 1999;86:1544–1550.

Auersperg N The origin of ovarian cancers—hypotheses and controversies Front Biosci Schol Ed 2013;5:709–719.

Dubeau L . The cell of origin of ovarian epithelial tumors and the ovarian surface epithelium dogma: does the emperor have no clothes? Gynecol Oncol 1999;72:437–442.

Banet N, Kurman RJ . Two types of ovarian cortical inclusion cysts: proposed origin and possible role in ovarian serous carcinogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2015;34:3–8.

Kurman RJ, Shih IeM . Molecular pathogenesis and extraovarian origin of epithelial ovarian cancer—shifting the paradigm. Hum Pathol 2011;42:918–931.

Boyd C, McCluggage WG . Low-grade ovarian serous neoplasms (low-grade serous carcinoma and serous borderline tumor) associated with high-grade serous carcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma: report of a series of cases of an unusual phenomenon. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:368–375.

Folkins AK, Jarboe EA, Saleemuddin A et al, A candidate precursor to pelvic serous cancer (p53 signature) and its prevalence in ovaries and fallopian tubes from women with BRCA mutations. Gynecol Oncol 2008;109:168–173.

Hutson R, Ramsdale J, Wells M . p53 protein expression in putative precursor lesions of epithelial ovariancancer. Histopathology 1995;27:367–371.

Pothuri B, Leitao MM, Levine DA et al, Genetic analysis of the early natural history of epithelial ovarian carcinoma. PLoS One 2010;5:e10358.

Bell DA, Scully RE . Early de novo ovarian carcinoma. A study of fourteen cases. Cancer 1994;73:1859–1864.

Rabban JT, Garg K, Crawford B et al, Early detection of high-grade tubal serous carcinoma in women at low risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome by systematic examination of fallopian tubes incidentally removed during benign surgery. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38:729–742.

Ambros RA, Sherman ME, Zahn CM, Bitterman P, Kurman RJ . Endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma: a distinctive lesion specifically associated with tumors displaying serous differentiation. Hum Pathol 1995;26:1260–1267.

Novak M, Lester J, Karst AM et al, Stathmin 1 and p16INK4A are sensitive adjunct biomarkers for serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2015;139:104–111.

Sehdev AS, Kurman RJ, Kuhn E, Shih IeM . Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma upregulates markers associated with high-grade serous carcinomas including Rsf-1 (HBXAP), cyclin E and fatty acid synthase. Mod Pathol 2010;23:844–855.

Kuhn E, Kurman RJ, Soslow RA et al, The diagnostic and biological implications of laminin expression in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:1826–1834.

Mehrad M, Ning G, Chen EY, Mehra KK, Crum CP . A pathologist's road map to benign, precancerous, and malignant intraepithelial proliferations in the fallopian tube. Adv Anat Pathol 2010;17:293–302.

Berek JS, Crum C, Friedlander M . Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;131 (Suppl 2):S111–S122.

Singh N, Gilks CB, Wilkinson N, McCluggage WG . Assessment of a new system for primary site assignment in high-grade serous carcinoma of the fallopian tube, ovary, and peritoneum. Histopathology 2015;67:331–337.

Falconer H, Yin L, Grönberg H, Altman D . Ovarian cancer risk after salpingectomy: a nationwide population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Committee Opinion. Salpingectomy for Ovarian Cancer Prevention Accessed on 22 February 2016. Available athttp://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Gynecologic-Practice/Salpingectomy-for-Ovarian-Cancer-Prevention.

Walker JL, Powell CB, Chen LM et al, Society of gynecologic oncology recommendations for the prevention of ovarian cancer. Cancer 2015;121:2108–2120.

Jacobs IJ, Menon U, Ryan A et al, Ovarian cancer screening and mortality in the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387:945–956.

Harmsen MG, Arts-de Jong M, Hoogerbrugge N et al, Early salpingectomy (TUbectomy) with delayed oophorectomy to improve quality of life as alternative for risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers (TUBA study): a prospective non-randomised multicentre study. BMC Cancer 2015;15:593.

Roh MH, Yassin Y, Miron A et al, High-grade fimbrial-ovarian carcinomas are unified by altered p53, PTEN and PAX2 expression. Mod Pathol 2010;23:1316–1324.

Howitt BE, Hanamornroongruang S, Lin DI et al, Evidence for a dualistic model of high-grade serous carcinoma: BRCA mutation status, histology, and tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:287–293.

Ritterhouse LL, Nowak JA, Strickland KC et al, Morphologic correlates of molecular alterations in extrauterine Müllerian carcinomas. Mod Pathol 2016;29:893–903.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the following for helpful discussions: T. Rinda Soong, MD, PhD, Jonathan S. Berek, MD, Ross S. Berkowitz MD, Kevin Elias, MD, Panagiotis Konstantinopoulus, MD PhD, Colleen Feltmate, MD, Barbara A. Goff, MD, Michael G. Muto, MD, William A. Peters III, MD. This work was funded by a grant from the Department of Defense (W81XWH-14–1–0504, to CPC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meserve, E., Brouwer, J. & Crum, C. Serous tubal intraepithelial neoplasia: the concept and its application. Mod Pathol 30, 710–721 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.238

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.238

This article is cited by

-

A questionnaire-based survey on the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for patients with STIC in Germany

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2023)

-

Recommendations for diagnosing STIC: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Virchows Archiv (2022)

-

Increase of fallopian tube and decrease of ovarian carcinoma: fact or fake?

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2021)