Abstract

A significant fraction of nasopharyngeal and sinonasal tumors are associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or human papillomavirus (HPV). Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) and extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma harbor EBV in practically all cases, although a small proportion of cases of the former harbor HPV. Sinonasal inverted papillomas harbor HPV in about 25% of cases. Sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas harbor transcriptionally active HPV in about 20% of cases, and limited data suggest that this subset has a better prognosis than the HPV-negative subset. This review addresses the diagnostic issues of the EBV-associated tumors. Difficulties in diagnosis of NPC may be encountered when there are prominent crush artifacts, many admixed lymphoid cells masking the neoplastic cells, or numerous interspersed granulomas, whereas benign cellular components (epithelial crypts and germinal centers) and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia can potentially be mistaken for NPC. Immunostaining for pan-cytokeratin and/or in situ hybridization for EBER can help in confirming or refuting a diagnosis of NPC. The main diagnostic problem of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma is recognition of the neoplastic nature of those examples predominated by small cells or showing a mixture of cells. The identification of a destructive infiltrate (dense expansile infiltrate; angiocentric growth) and definite cytologic atypia (clear cells; many medium-sized cells) would favor a diagnosis of lymphoma, which can be supported by immunohistochemistry (most commonly CD3+, CD5−, CD56+) and in situ hybridization for EBER. In conclusion, among nasopharyngeal and sinonasal neoplasms, demonstration of EBV may aid in diagnosis, particularly NPC and extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma. Demonstration of HPV does not have a role yet in diagnosis, although this may change in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Virus-associated neoplasms of the nasopharynx and sinonasal tract

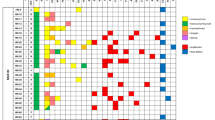

A significant fraction of tumors arising in the nasopharynx and sinonasal tract are associated with virus, in particular Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and human papillomavirus (HPV) (Table 1). Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) and extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma harbor EBV in practically all cases, although a small proportion of cases of NPC are positive for HPV but negative for EBV, identified predominantly in Caucasians.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 The clinical and prognostic significance of the latter subset vs conventional EBV-positive NPC remains to be clarified.

The reported frequencies of HPV detection in various head and neck tumors have spanned wide ranges, due to the use different methodologies in different studies. In particular, the mere detection of HPV DNA in a tumor does not distinguish between viral-mediated carcinogenesis and ‘bystander’ infection. The figures cited in the following are based on data from several large systematic reviews.10, 11, 12 Approximately 20–25% of cases of sinonasal Schneiderian inverted papillomas without dysplasia or carcinoma harbor HPV, with a low-risk to high-risk HPV ratio of 4.8 : 1. However, for Schneiderian papilloma complicated by squamous cell carcinoma, a higher proportion of cases (55%) harbor HPV, with a low-risk to high-risk HPV ratio of 1 : 2.4.11, 12 The significance of HPV in tumorigenesis of this neoplasm is still unclear. About 15–25% of cases of sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas harbor transcriptionally active HPV.10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 They usually show a nonkeratinizing morphology, only rarely arise from a preexisting Schneiderian papilloma, and the limited data suggest a better prognosis compared with HPV-negative tumors, akin to oropharyngeal carcinoma.12, 13, 15, 17 A newly described entity of the sinonasal tract termed ‘HPV-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features’ shows a definitional link with HPV.18

This review focuses on the diagnostic issues of NPC and extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, and illustrates the value of demonstration of EBV in problematic cases.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

NPC shows marked differences in incidence in different parts of the world, being most prevalent among southern Chinese.19 NPC is also remarkable for the very strong association with EBV. Three histologic types of NPC are recognized: (1) keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, (2) nonkeratinizing carcinoma (differentiated or undifferentiated), and (3) basaloid squamous cell carcinoma.19

Histologic Types of NPC

Keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma

Keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma most commonly arises de novo, but can occur as a radiation-induced carcinoma that develops after radiation therapy for nonkeratinizing NPC.20, 21, 22 Compared with nonkeratinizing carcinoma, the tumor is more commonly advanced (76% vs 55%), whereas lymph node metastasis is less common (29% vs 70%).23, 24 The tumor typically grows in the form of irregular islands, often accompanied by an abundant desmoplastic stroma. There is obvious squamous differentiation, in the form of keratinization and intercellular bridges (Figure 1).25 That is, the tumor is morphologically similar to squamous cell carcinomas arising in other mucosal sites of the head and neck.

EBV is often positive in nasopharyngeal keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas occurring in areas endemic for NPC, but only infrequently positive in low incidence areas.26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 When positive, the EBV copy number in the tumor cells tends to be low.37 On the other hand, radiation-induced keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma lacks association with EBV.22

Nonkeratinizing carcinoma

Nonkeratinizing carcinoma, the commonest histologic type of NPC, shows near consistent association with EBV.38, 39, 40, 41 Morphologic evidence of squamous differentiation is usually lacking at the light microscopic level. The density of lymphocytes and plasma cells is highly variable.

Undifferentiated carcinoma is characterized by islands and sheets of syncytial-appearing large tumor cells with indistinct cell borders, round or oval vesicular nuclei, and large central nucleoli (Figure 2,Figure 3). The cells often appear crowded or even overlapping. They can sometimes be spindly, forming streaming fascicles (Figure 4). Exceptionally, a reticulated-myxoid pattern is formed (Figure 5). Lymphoepithelial carcinoma refers to those examples accompanied by a profuse infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells, both within and between the tumor islands (Figure 6). In ~12% of cases of NPC, there are tumor-associated amyloid globules, which can occur within the tumor cells causing indentation of the nucleus, between tumor cells, or in the subjacent stroma (Figure 7).42 As amyloid globules are practically never seen in the normal nasopharyngeal mucosa, their presence can provide additional support to the diagnosis of NPC for a nasopharyngeal biopsy showing suspicious epithelial islands.

Differentiated carcinoma shows cellular stratification and pavementing, often with a plexiform growth, reminiscent of urothelial carcinoma.25 The relatively small tumor cells show fairly well-defined cell borders and sometimes vague intercellular bridges (Figure 8). Compared with the undifferentiated subtype, the nuclei tend to be more chromain-rich and nucleoli are less prominent.

Differentiated nonkeratinizing carcinoma of the nasopharynx. The tumor comprises anastomosing sheets with pavementing of the cells at the peripheral portion (left). The tumor cells show fairly well-defined cell borders and vague intercellular bridges. The nuclei are often more hyperchromatic than those of undifferentiated carcinoma (right).

Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma

Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the nasopharynx is very rare. Histologically, the tumor comprises lobular masses, sometimes with jigsaw-puzzle configuration, and festoons of mitotically active basaloid cells with pale-staining or hyperchromatic nuclei, interspersed with variable amounts of mucoid matrix or hyaline material (Figure 9). Comedo necrosis is common. There should also be an identifiable component of squamous cell carcinoma, which can be invasive or in situ. Among four cases tested for EBV, all three Asian cases are positive, whereas one Caucasian case is negative.43, 44 From the limited data, the tumor may not be as aggressive as morphologically identical tumors occurring in other head and neck sites.

Problems in Rendering a Diagnosis of NPC on Nasopharyngeal Biopsies

Crush artifacts causing problems in diagnosis

Crush artifacts, which are common in biopsies, can render it difficult to determine whether there is malignancy. In particular, it may be impossible to tell whether the distorted cells represent carcinoma cells or merely crushed reactive lymphoid cells (Figure 10). The correct diagnosis of NPC may be reached by finding better preserved cells in the biopsy, where tumor cell cluster formation and cytologic atypia are more convincing. If there are no well-preserved areas in the biopsy and one is worried about the possibility of carcinoma, immunostaining for cytokeratin is of great help. In the non-neoplastic nasopharyngeal mucosa, cytokeratin immunostaining highlights the sharply delineated surface and crypt epithelium, with no positive cells in the stroma. NPC typically shows irregular infiltrative clusters of cytokeratin-positive cells (Figure 10).

NPC masked by lymphoid cells or granulomas

In some examples of NPC, particularly the lymphoepithelial variant, the tumor is so densely infiltrated by lymphocytes and plasma cells that the individual carcinoma cells can be mistaken for lymphoma cells (Figure 11). In contrast to the latter, their cell borders are poorly defined. Intercellular or intracellular spherical amyloid globules, if present, points strongly towards a diagnosis of NPC. It is most helpful to examine the tissue at medium magnification, wherein the cohesive growth of the tumor usually becomes more evident, pointing to the epithelial nature of the cellular proliferation (Figure 11). The diagnosis of NPC can be further confirmed by positive immunostaining for cytokeratin.

Rare cases of NPC are accompanied by epithelioid granulomas, which may mask the tumor islands. The granuloma may represent a host immune reaction to the neoplasm, or a coincidental occurrence due to infection (such as tuberculosis) or unknown causes. As granulomatous inflammation is uncommon in the nasopharynx, a nasopharyngeal biopsy showing granulomas should always be scrutinized for NPC.

Benign cellular components mimicking nonkeratinizing carcinoma

Germinal centers can mimic carcinoma by virtue of their occurrence as cellular clusters (sometimes lacking well-defined mantle zones) and presence of large cells with vesicular nuclei and distinct nucleoli (Figure 12). The identification of admixed centrocytes (smaller ‘atypical’ cells with irregular-shaped or angulated nuclei) and tingible-body macrophages would provide the clue that the large cells represent germinal center lymphoid cells (Figure 12). This can be further confirmed by immunostaining, with the large cells being negative for cytokeratin, and positive for B-lineage marker (such as CD20).

Nasopharyngeal mucosa without malignancy. Aggregates of germinal center cells may impart a resemblance to nasopharyngeal carcinoma because of the presence of ‘atypical’ nuclei (left). On low magnification, it is evident that these cells form discrete round aggregates, and are confined to lymphoid follicles (right).

Tangentially sectioned crypts may be mistaken for islands of carcinoma because of their deep location, presence of enlarged vesicular nuclei, and expansion by intraepithelial lymphocytes (Figure 13). In contrast to NPC, there is no frank invasive growth, the nuclei are not as large and thus do not appear as crowded, and the nucleoli are not as prominent. On immunostaining for cytokeratin, the smooth contours of the crypts become obvious. Continuity with the surface epithelium can sometimes be demonstrated.

Tangentially sectioned crypt in nasopharyngeal mucosa. A solid island of epithelial cells with mild nuclear enlargement and distinct nucleoli may mimic nasopharyngeal carcinoma (left). The correct interpretation is supported by the smooth contour of the cell island, continuity with a definite crypt, and lack of invasive growth (right).

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia mimicking NPC

In reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the nasopharyngeal mucosa (including infectious mononucleosis), there can be a remarkable increase of large lymphoid cells (immunoblasts), raising a suspicion of carcinoma (Figure 14). In contrast to NPC, the large cells are non-cohesive and have well-defined amphophilic to plasmacytoid rather than eosinophilic cytoplasm. There is often apparent maturation of the immunoblasts into plasmablasts (nuclei slightly smaller and chromatin more coarsely clumped compared with immunoblasts) and plasma cells. The diagnosis can be further confirmed by positive immunostaining of the large cells for lymphoid markers and lack immunoreactivity for cytokeratin.

Large cell lymphoma mimicking nonkeratinizing carcinoma and vice versa

Distinction between NPC and large cell lymphoma can at times be very difficult, especially as NPC cells can appear deceptively non-cohesive due to the presence of many admixed lymphocytes and plasma cells. On the other hand, the interface of a large cell lymphoma with the residual lymphoid tissues can be deceptively sharp, mimicking carcinoma (Figure 15). Features favoring a diagnosis of NPC are presence of definite cohesive cell groups, poorly defined cell borders and large eosinophilic nucleoli, whereas features favoring a diagnosis of large cell lymphoma are permeative single-file infiltrations, amphophilic cytoplasm, and marked nuclear foldings.

Diagnostic Issues of NPC Presenting Initially as Lymphadenopathy

NPC, not uncommonly, presents initially as cervical lymph node metastases (Figure 16). The diagnosis of carcinoma is usually straight-forward; a nasopharyngeal primary can be suggested by the location of the involved lymph node (especially jugulo-digastric node) and the syncytial appearance of the tumor cells (Figure 16). The clinical scenario, morphology, and positive in situ hybridization for EBER will further provide a strong support for a nasopharyngeal origin (Figure 16). However, morphologically identical tumors can also rarely be derived from oropharyngeal HPV-related lymphoepitheioma-like carinoma.45 These tumors are negative for EBER, but positive for p16 and high-risk HPV.

Lymph node harboring metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Confluent islands of undifferentiated carcinoma are found in the nodal parenchyma (left). The tumor cells typically have indistinct cell borders, vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli (right upper). Positive labeling for EBER by in situ hybridization is helpful for confirming the diagnosis (right lower).

Lymph nodes showing focal or patchy involvement by NPC may mimic reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, or classical Hodgkin lymphoma as a result of submergence of the tumor cells in a lymphocyte-rich background.46, 47, 48 Furthermore, in approximately one-fifth of cases, there are epithelioid granulomas (sometimes necrotizing), which can mask the metastatic NPC (Figure 17).49 The most helpful clues to diagnoses are the syncytial quality of the large atypical cells and presence of cellular clusters at medium magnification. Diagnosis can be readily confirmed by cytokeratin immunostain.

Assessment of Post-Treatment Biopsies in Patients with NPC

Persistent tumor on biopsy

After radiation therapy, it may take up to 10 weeks for all the carcinoma cells to disappear histologically.50 The ‘persistent’ radiated carcinoma cells usually show injury in the form of enlarged and bizarre nuclei—the nuclear pleomorphism in general exceeds that seen in non-radiated NPC. However, as the nuclear enlargement is accompanied by an increased amount of cytoplasm, the nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio is preserved (Figure 18). As presence of residual tumor histologically within 10 weeks of completion of radiotherapy does not necessarily mean persistent or resistant tumor, this per se is not a sufficient indicator for the intensification of treatment. The biopsy can be reported as ‘Residual carcinoma cells present, but uncertain as to whether they are viable. Suggest to repeat biopsy in 2 weeks.’ Remission is defined by two subsequent negative biopsies.50, 51, 52 On the other hand, residual tumor observed in biopsies taken more than 10 weeks after completion of radiotherapy can be reported directly as presence of residual carcinoma.

Radiation change in normal tissues

Radiation-induced changes in the normal nasopharyngeal mucosa can mimic malignancy. The cells in the surface or crypts can exhibit enlarged, hyperchromatic, or even bizarre nuclei. However, such changes can be recognized as being benign because the large atypical cells often occur singly among normal-looking epithelial cells (random cytologic atypia) and the nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio is maintained (Figure 19). Radiation-induced epithelial atypia should not persist beyond 1 year, because the abnormal cells are normally shed and replaced by proliferated cells from the basal layer cells. If there are uncertainties as to whether the atypical cells represent carcinoma cells or irradiated normal epithelial cells, positive in situ hybridization for EBER would strongly favor the former interpretation.

Normal nasopharyngeal epithelium with radiation change. In the epithelium, occasional nuclei are enlarged and hyperchromatic, but they are found among normal-looking nuclei (left). ‘Bizarre’ radiation fibroblasts in the stroma of the nasopharyngeal mucosa. These cells do not form cohesive groups, are stellate to spindly, and show amphophilic cytoplasm (right).

After radiotherapy, it is common to find bizarre stromal cells (radiation fibroblasts) in the mucosa, and these cells can persist for years. Bizarre stromal cells are plump, spindly, or ovoid, and possess large nuclei with smudged chromatin, but some cells can have large vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Figure 19). They can be distinguished from residual or recurrent carcinoma by their occurrence as single cells rather than cellular clusters and by the striking amphophilia of the cytoplasm. These cells are negative for cytokeratin and EBER. The stroma frequently contains ectatic blood vessels showing variable degrees of radiation injury such as prominent endothelial cells and abundant fibrinoid deposits.

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma is a predominantly extranodal lymphoma characterized by vascular damage, prominent necrosis, cytotoxic phenotype, and association with EBV. It may be of NK-cell lineage (majority) or cytotoxic T-cell lineage.53

Clinical Features

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma is more prevalent in Asians, and the native American population of Mexico, Central America and South America. It occurs most often in adults, with a reported median age of 44-54 years, with male predominance.53

The upper aerodigestive tract (nasal cavity, nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses, and palate) is most commonly involved, with the nasal cavity being the prototypic site of involvement. Patients with nasal involvement present with symptoms of nasal obstruction or epistaxis due to presence of a mass lesion, or with extensive midfacial destructive lesions. The lymphoma can extend to the adjacent tissues, such as the nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses, orbit, oral cavity, palate, and oropharynx. The disease is often localized to the upper aerodigestive tract at presentation. However, it may disseminate to various sites, eg skin, gastrointestinal tract, testis, or cervical lymph nodes during the clinical course. The prognosis of nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma is variable, with some patients responding well to therapy and others dying of disseminated disease despite aggressive therapy. Historically, the survival rate was poor (30−40%), but it has improved in recent years with more intensive therapy including upfront radiotherapy.54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphomas occurring outside the upper aerodigestive tract (often referred to as ‘extranasal NK/T-cell lymphomas’) show predilection for skin, soft tissue, gastrointestinal tract, and testis. The patients commonly have high stage disease at presentation, with involvement of multiple extranodal sites. Systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, and weight loss can be present. The disease is very aggressive, with most patients dying within 1-2 years.62, 63

Pathology

The mucosa shows a diffuse and dense lymphomatous infiltrate, often accompanied by ulceration and necrosis (Figure 20). Mucosal glands often become widely spaced or are lost (Figure 20). An angiocentric and angiodestructive growth pattern is frequently present (Figure 20). Florid pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the overlying epithelium can occur in some cases (Figure 21).53

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma of nasal cavity. The mucosa shows a dense infiltrate of lymphoid cells. The surface epithelium is intact in this example (left upper). This example shows the typical ulceration and necrosis (right upper). The lymphomatous infiltrate causes wide separation or disappearance of mucosal glands. Clear cell change is common in the residual mucosal glands (left lower). Angiocentric growth is a common feature (right lower).

The cytological spectrum is broad. The cells may be small, medium-sized, large, or anaplastic (Figure 22). In most cases, the lymphoma is composed of medium-sized cells or a mixture of small and medium-sized cells. The cells often have irregularly folded nuclei, which can be elongated. The chromatin is granular, except in the very large cells, which may have vesicular nuclei. Nucleoli are generally inconspicuous or small. The cytoplasm is moderate in amount and often pale to clear. Mitotic figures are easily found, even for small cell-predominant lesions.

Immunophenotype

The most typical immunophenotype of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma is: CD2+, CD5−, CD56+, surface CD3− (as demonstrated on fresh or frozen tissue) and cytoplasmic CD3ɛ+ (as demonstrated on fresh, frozen, or fixed tissue) (Figure 23).53, 62, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69 CD56, although a highly useful marker for NK-cells, is not entirely specific and can be expressed in some peripheral T-cell lymphomas and non-hematolymphoid malignancies. CD43 and CD45RO are often positive, and CD7 is variably expressed. Other T- and NK-cell-associated antigens, including CD4, CD8, CD16, and CD57, are usually negative. The subset of cases of cytotoxic T-cell lineage may express CD5, CD8, and T-cell receptor (γδ or αß).70, 71, 72 Cytotoxic molecules (such as granzyme B, TIA-1, and perforin) are positive (Figure 23).73 CD30 is positive in about 30% of cases.62, 74, 75, 76, 77

In situ hybridization for EBV encoded RNA (EBER) is the most reliable way to demonstrate presence of EBV, with virtually all lymphoma cells being labeled (Figure 23).

Nasal Lymphoid Infiltrate: Lymphoma or Reactive Lymphoid Infiltrate?

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, particularly those examples predominated by small or mixed cell populations, or those accompanied by a heavy admixture of inflammatory cells (small lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, and eosinophils) may mimic a reactive lymphoid infiltrate. The difficulties in diagnosis are compounded by the fact that the mucosal small lymphoid cells often show mild atypia, with slight nuclear enlargement and irregularities, cytologically overlapping with extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma (Figure 24). Presence of some or all of the following features would favor a diagnosis of lymphoma: (1) dense infiltrate causing separation or destruction of the mucosal glands (Figure 20), (2) prominent tissue necrosis and ulceration, (3) angioinvasion, (4) presence of mitotic figures in a small cell-predominant lymphoid infiltrate, (5) clear cells, and (6) a significant population of atypical medium-sized cells with irregular nuclei (Figure 25). The diagnosis can be confirmed by immunohistochemical demonstration of sheets of CD3ɛ+ CD56+ cells. If the infiltrate is CD3ɛ+ CD56−, positive immunostaining for TIA-1 and in situ hybridization for EBER will support the diagnosis.

Wegener granulomatosis, a destructive lesion of the upper respiratory tract, shares many morphologic features with nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma in the form of mixed inflammatory infiltrate, ulceration, necrosis, and vasculitis or vasculitis-like lesions. The same features helpful for distinction between NK/T-cell lymphoma and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia also apply.

Herpes simplex infection can simulate nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma due to the presence of a mass lesion, a dense lymphoid infiltrate with necrosis, and CD56 expression by the lymphoid cells.78 The presence of scattered herpes virus inclusions, lack of angioinvasion, expression of CD4 by the T-cell infiltrate, and absence of EBV support this diagnosis over NK/T-cell lymphoma.

Conclusions

In the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal and sinonasal neoplasms, demonstration of EBV may aid in the diagnosis of NPC and extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma because of the very strong association of these tumors with EBV. Currently, demonstration of HPV does not have a role in the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal and sinonasal neoplasms, except for HPV-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features. However, the practice may change in future if there are convincing data to indicate a favorable prognostic significance of HPV in sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas.

References

Thavaraj S . Human papillomavirus-associated neoplasms of the sinonasal tract and nasopharynx. Semin Diagn Pathol 2016; 33: 104–111.

Svajdler M Jr., Kaspirkova J, Mezencev R et al, Human papillomavirus and Epstein-Barr virus in nasopharyngeal carcinoma in a non-endemic eastern European population. Neoplasma 2016; 63: 107–114.

Stenmark MH, McHugh JB, Schipper M et al, Nonendemic HPV-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma: association with poor prognosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014; 88: 580–588.

Singhi AD, Califano J, Westra WH . High-risk human papillomavirus in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck 2012; 34: 213–218.

Robinson M, Suh YE, Paleri V et al, Oncogenic human papillomavirus-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an observational study of correlation with ethnicity, histological subtype and outcome in a UK population. Infect Agent Cancer 2013; 8: 30.

Maxwell JH, Kumar B, Feng FY et al, HPV-positive/p16-positive/EBV-negative nasopharyngeal carcinoma in white North Americans. Head Neck 2010; 32: 562–567.

Dogan S, Hedberg ML, Ferris RL et al, Human papillomavirus and Epstein-Barr virus in nasopharyngeal carcinoma in a low-incidence population. Head Neck 2014; 36: 511–516.

Lin Z, Khong B, Kwok S et al, Human papillomavirus 16 detected in nasopharyngeal carcinomas in white Americans but not in endemic Southern Chinese patients. Head Neck 2014; 36: 709–714.

Lo EJ, Bell D, Woo J et al, Human papillomavirus & WHO type I nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Laryngoscope 2010; 120: S185.

Isayeva T, Li Y, Maswahu D et al, Human papillomavirus in non-oropharyngeal head and neck cancers: a systematic literature review. Head Neck Pathol 2012; 6: S104–S120.

Lawson W, Schlecht NF, Brandwein-Gensler M . The role of the human papillomavirus in the pathogenesis of Schneiderian inverted papillomas: an analytic overview of the evidence. Head Neck Pathol 2008; 2: 49–59.

Lewis JS Jr., Westra WH, Thompson LD et al, The sinonasal tract: another potential ‘hot spot’ for carcinomas with transcriptionally-active human papillomavirus. Head Neck Pathol 2014; 8: 241–249.

Bishop JA, Guo TW, Smith DF et al, Human papillomavirus-related carcinomas of the sinonasaltract. Am J Surg Pathol 2013; 37: 185–192.

Syrjanen K, Syrjanen S . Detection of human papillomavirus in sinonasal carcinoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Pathol 2013; 44: 983–991.

Laco J, Sieglova K, Vosmikova H et al, The presence of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) E6/E7 mRNA transcripts in a subset of sinonasal carcinomas is evidence of involvement of HPV in its etiopathogenesis. Virchows Arch 2015; 467: 405–415.

Larque AB, Hakim S, Ordi J et al, High-risk human papillomavirus is transcriptionally active in a subset of sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas. Mod Pathol 2014; 27: 343–351.

Alos L, Moyano S, Nadal A et al, Human papillomaviruses are identified in a subgroup of sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas with favorable outcome. Cancer 2009; 115: 2701–2709.

Bishop JA, Ogawa T, Stelow EB et al, Human papillomavirus-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features: a peculiar variant of head and neck cancer restricted to the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol 2013; 37: 836–844.

Chan JKC, Bray F, McCarron P et al, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, et al. (eds). Pathology and Genetics. Head and Neck Tumours. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. IARC: Lyon, 2005, pp 85-97.

Shanmugaratnam K . Histological typing of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. IARC Sci Publ 1978; 3–12.

Weiland LH . The histopathological spectrum of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. IARC Sci Publ 1978; 41–50.

Chen CL, Hsu MM . Second primary epithelial malignancy of nasopharynx and nasal cavity after successful curative radiation therapy of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Hum Pathol 2000; 31: 227–232.

Reddy SP, Raslan WF, Gooneratne S et al, Prognostic significance of keratinization in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Am J Otolaryngol 1995; 16: 103–108.

Neel HB 3rd . Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1985; 18: 479–490.

Shanmugaratnam K, Sobin LH, Barnes L . Histological Typing of Tumors of the Upper Respiratory Tract and Ear. International histological classification of tumors, 2nd edn. Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 1991.

Niedobitek G, Hansmann ML, Herbst H et al, Epstein-Barr virus and carcinomas: undifferentiated carcinomas but not squamous cell carcinomas of the nasopharynx are regularly associated with the virus. J Pathol 1991; 165: 17–24.

Dickens P, Srivastava G, Loke SL et al, Epstein-Barr virus DNA in nasopharyngeal carcinomas from Chinese patients in Hong Kong. J Clin Pathol 1992; 45: 396–397.

Chen CL, Wen WN, Chen JY et al, Detection of Epstein-Barr virus genome in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by in situ DNA hybridization. Intervirology 1993; 36: 91–98.

Hording U, Nielsen HW, Albeck H et al, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: histopathological types and association with Epstein-Barr Virus. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 1993; 29B: 137–139.

Della Torre G, Pilotti S, Donghi R et al, Epstein-Barr virus genomes in undifferentiated and squamous cell nasopharyngeal carcinomas in Italian patients. Diagn Mol Pathol 1994; 3: 32–37.

Gulley ML, Amin MB, Nicholls JM et al, Epstein-Barr virus is detected in undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma but not in lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Hum Pathol 1995; 26: 1207–1214.

Hwang TZ, Jin YT, Tsai ST . EBER in situ hybridization differentiates carcinomas originating from the sinonasal region and the nasopharynx. Anticancer Res 1998; 18: 4581–4584.

Inoue H, Sato Y, Tsuchiya B et al, Expression of Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small nuclear RNA 1 in Japanese nasopharyngeal carcinomas. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002; 547: 113–117.

Kanavaros P, Kouvidou C, Dai Y . MDM-2 protein expression in nasopharyngeal carcinomas—comparative study with p53 expression. J Clin Pathol 1995; 48: M322–M325.

Pathmanathan R, Prasad U, Chandrika G et al, Undifferentiated, nonkeratinizing, and squamous cell carcinoma of the nasopharynx. Variants of Epstein-Barr virus-infected neoplasia. Am J Pathol 1995; 146: 1355–1367.

Nicholls JM, Agathanggelou A, Fung K et al, The association of squamous cell carcinomas of the nasopharynx with Epstein-Barr virus shows geographical variation reminiscent of Burkitt’s lymphoma. J Pathol 1997; 183: 164–168.

Raab-Traub N, Flynn K, Pearson G et al, The differentiated form of nasopharyngeal carcinoma contains Epstein-Barr virus DNA. Int J Cancer 1987; 39: 25–29.

Tsai ST, Jin YT, Mann RB et al, Epstein-Barr virus detection in nasopharyngeal tissues of patients with suspected nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer 1998; 82: 1449–1453.

Sam CK, Brooks LA, Niedobitek G et al, Analysis of Epstein-Barr virus infection in nasopharyngeal biopsies from a group at high risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer 1993; 53: 957–962.

Vasef MA, Ferlito A, Weiss LM . Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, with emphasis on its relationship to Epstein-Barr virus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1997; 106: 348–356.

Hsiao JR, Jin YT, Tsai ST . EBER1 in situ hybridization as an adjuvant for diagnosis of recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Anticancer Res 1998; 18: 4585–4589.

Prathap K, Looi LM, Prasad U . Localized amyloidosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Histopathology 1984; 8: 27–34.

Wan SK, Chan JK, Lau WH et al, Basaloid-squamous carcinoma of the nasopharynx. An Epstein-Barr virus-associated neoplasm compared with morphologically identical tumors occurring in other sites. Cancer 1995; 76: 1689–1693.

Muller E, Beleites E . The basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the nasopharynx. Rhinology 2000; 38: 208–211.

Singhi AD, Stelow EB, Mills SE et al, Lymphoepithelial-like carcinoma of the oropharynx: a morphologic variant of HPV-related head and neck carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2010; 34: 800–805.

Carbone A, Micheau C . Pitfalls in microscopic diagnosis of undifferentiated carcinoma of nasopharyngeal type (lymphoepithelioma). Cancer 1982; 50: 1344–1351.

Zarate-Osorno A, Jaffe ES, Medeiros LJ . Metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma initially presenting as cervical lymphadenopathy. A report of two cases that resembled Hodgkin’s disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1992; 116: 862–865.

Charafe-Jauffret E, Bertucci F, Ramuz O et al, Characterization of Hodgkin’s lymphoma-like undifferentiated carcinoma of the nasopharyngeal type as a particular UCNT subtype mimicking Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Int J Oncol 2003; 23: 97–103.

Lennert K, Kaiserling E, Mazzanti T . Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of lymphoepithelial carcinoma in lymph nodes: histological, cytological and electron-microscopic findings. IARC Sci Publ 1978; 20: 51–64.

Kwong DL, Nicholls J, Wei WI et al, The time course of histologic remission after treatment of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer 1999; 85: 1446–1453.

Kwong DL, Nicholls J, Wei WI et al, Correlation of endoscopic and histologic findings before and after treatment for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck 2001; 23: 34–41.

Nicholls JM, Sham J, Chan CW et al, Radiation therapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: histologic appearances and patterns of tumor regression. Hum Pathol 1992; 23: 742–747.

Chan JKC, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Ferry JA et al, Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal-type. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. (eds). WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th edn. IARC: Lyon, 2003, pp 285–288.

Barrionuevo C, Zaharia M, Martinez MT et al, Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: study of clinicopathologic and prognosis factors in a series of 78 cases from Peru. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2007; 15: 38–44.

Cheung MM, Chan JK, Lau WH et al, Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the nose and nasopharynx: clinical features, tumor immunophenotype, and treatment outcome in 113 patients. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 70–77.

Cheung MM, Chan JK, Lau WH et al, Early stage nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma: clinical outcome, prognostic factors, and the effect of treatment modality. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002; 54: 182–190.

Chim CS, Ma SY, Au WY et al, Primary nasal natural killer cell lymphoma: long-term treatment outcome and relationship with the International Prognostic Index. Blood 2004; 103: 216–221.

Cuadra-Garcia I, Proulx GM, Wu CL et al, Sinonasal lymphoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 58 cases from the Massachusetts General Hospital. Am J Surg Pathol 1999; 23: 1356–1369.

Ko YH, Ree HJ, Kim WS et al, Clinicopathologic and genotypic study of extranodal nasal-type natural killer/T-cell lymphoma and natural killer precursor lymphoma among Koreans. Cancer 2000; 89: 2106–2116.

Kwong YL, Chan AC, Liang R et al, CD56+ NK lymphomas: clinicopathological features and prognosis. Br J Haematol 1997; 97: 821–829.

Liang R, Todd D, Chan TK et al, Treatment outcome and prognostic factors for primary nasal lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13: 666–670.

Au WY, Weisenburger DD, Intragumtornchai T et al, Clinical differences between nasal and extranasal NK/T-cell lymphoma: a study of 136 cases from the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project. Blood 2008; 113: 3931–3937.

Wong KF, Chan JK, Ng CS . NCAM (CD56)-positive malignant lymphoma. Blood 1992; 80: 2431–2432.

Chan JK . Natural killer cell neoplasms. Anat Pathol 1998; 3: 77–145.

Chan JK, Tsang WY, Pau MY . Discordant CD3 expression in lymphomas when studied on frozen and paraffin sections. Hum Pathol 1995; 26: 1139–1143.

Jaffe ES . Nasal and nasal-type T/NK cell lymphoma: a unique form of lymphoma associated with the Epstein-Barr virus [comment]. Histopathology 1995; 27: 581–583.

Jaffe ES, Chan JK, Su IJ et al, Report of the Workshop on nasal and related extranodal angiocentric T/natural killer cell lymphomas: definitions, differential diagnosis, and epidemiology. Am J Surg Pathol 1996; 20: 103–111.

Tsang WY, Chan JK, Ng CS et al, Utility of a paraffin section-reactive CD56 antibody (123C3) for characterization and diagnosis of lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol 1996; 20: 202–210.

Quintanilla-Martinez L, Franklin JL, Guerrero I et al, Histological and immunophenotypic profile of nasal NK/T cell lymphomas from Peru: high prevalence of p53 overexpression. Hum Pathol 1999; 30: 849–855.

Pongpruttipan T, Sukpanichnant S, Assanasen T et al, Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, includes cases of natural killer cell and alphabeta, gammadelta, and alphabeta/gammadelta T-cell origin: a comprehensive clinicopathologic and phenotypic study. Am J Surg Pathol 2012; 36: 481–499.

Jhuang JY, Chang ST, Weng SF et al, Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type in Taiwan: a relatively higher frequency of T-cell lineage and poor survival for extranasal tumors. Hum Pathol 2015; 46: 313–321.

Yamaguchi M, Takata K, Yoshino T et al, Prognostic biomarkers in patients with localized natural killer/T-cell lymphoma treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Cancer Sci 2014; 105: 1435–1441.

Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Zarate-Osorno A, Meneses A et al, Cytotoxic granular protein expression, Epstein-Barr virus strain type, and latent membrane protein-1 oncogene deletions in nasal T- lymphocyte/natural killer cell lymphomas from Mexico. Mod Pathol 1998; 11: 754–761.

Li S, Feng X, Li T et al, Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: a report of 73 cases at MD Anderson Cancer Center. Am J Surg Pathol 2013; 37: 14–23.

Kuo TT, Shih LY, Tsang NM . Nasal NK/T cell lymphoma in Taiwan: a clinicopathologic study of 22 cases, with Analysis of histologic subtypes, Epstein-Barr virus LMP-1 Gene association, and treatment modalities. Int J Surg Pathol 2004; 12: 375–387.

Kim WY, Nam SJ, Kim S et al, Prognostic implications of CD30 expression in extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma according to treatment modalities. Leuk Lymphoma 2015; 56: 1778–1786.

Gualco G, Domeny-Duarte P, Chioato L et al, Clinicopathologic and molecular features of 122 Brazilian cases of nodal and extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, with EBV subtyping analysis. Am J Surg Pathol 2011; 35: 1195–1203.

Taddesse-Heath L, Feldman JI, Fahle GA et al, Florid CD4+, CD56+ T-cell infiltrate associated with Herpes simplex infection simulating nasal NK-/T-cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol 2003; 16: 166–172.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, J. Virus-associated neoplasms of the nasopharynx and sinonasal tract: diagnostic problems. Mod Pathol 30 (Suppl 1), S68–S83 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.189

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.189

This article is cited by

-

Challenging Tumor Heterogeneity with HER2, p16 and Somatostatin Receptor 2 Expression in a Case of EBV-Associated Lymphoepithelial Carcinoma of the Salivary Gland

Head and Neck Pathology (2023)

-

Revealing the crosstalk between nasopharyngeal carcinoma and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2022)