Abstract

Histologic classification of ampullary carcinomas as intestinal versus pancreatobiliary is rapidly becoming a part of management algorithms, with immunohistochemical classification schemes also being devised using this classification scheme as their basis. However, data on the reproducibility and prognostic relevance of this classification system are limited. In this study, five observers independently evaluated 232 resected ampullary carcinomas with invasive component >3 mm. Overall interobserver agreement was ‘fair’ (κ 0.39; P<0.001) with complete agreement in 23%. Using agreement by 3/5 observers as ‘consensus’ 40% of cases were classified as ‘mixed’ pancreatobiliary and intestinal. When observers were asked to provide a final diagnosis based on the predominant pattern in cases initially classified as mixed, there was ‘moderate’ agreement (κ 0.44; P<0.0001) with 5/5 agreeing in 35%. Cases classified as pancreatobiliary by consensus (including those with pure-pancreatobiliary or mixed-predominantly pancreatobiliary features) had shorter overall (median 41 months) and 5-year survival (38%) than those classified as pure-intestinal/mixed-predominantly intestinal (80 months and 57%, respectively; P=0.026); however, on multivariate analysis this was not independent of established prognostic parameters. Interestingly, when compared with 476 cases of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, the pancreatobiliary-type ampullary carcinomas had better survival (16 versus 41 months, P<0.001), even when matched by size and node status. In conclusion, presumably because of the various cell types comprising the region, ampullary carcinomas frequently show mixed phenotypes and intratumoral heterogeneity, which should be considered when devising management protocols. Caution is especially warranted when applying this histologic classification to biopsies and tissue microarrays. While ampullary carcinomas with more pancreatobiliary morphology have a worse prognosis than intestinal ones this does not appear to be an independent prognostic factor. However, pancreatobiliary-type ampullary carcinomas have a much better prognosis than their pancreatic counterparts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The ampulla of Vater is composed of multiple cell types. The duodenum-facing surface is covered partially by intestinal-type epithelium, which transitions into a specialized epithelium (of gastric foveolar type with intermixed goblet cells) at the ‘papilla’, and, on the wall, there resides ‘pancreatobiliary-type’ ductules, which show morphologic characteristics of pancreatobiliary ducts but also often express the intestinal transcription factor caudal-type homeobox 2 (CDX2).

It has long been noted that the carcinomas arising in this region may resemble colonic or pancreatobiliary adenocarcinomas, and are presumed to carry with them the prognostic stigmata associated with these carcinoma types, which for the former are relatively indolent, but highly dismal for the latter. Accordingly, a cell-lineage-based classification scheme has been proposed for these tumors—pancreatobiliary and intestinal.1, 2, 3 In fact, this has spawned several newly designed and revised treatment protocols with many oncologists now requiring and utilizing this classification for management purposes.

Recently, immunohistochemical panels have been proposed in an attempt to further substantiate this classification.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 However, in each of these immunohistochemical studies, different and sometimes complex combinations of markers have been advocated, many of which are arbitrarily defined,4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 16, 17, 18, 19 with their primary validation using histomorphologic classification as the ‘gold standard’. Furthermore, many of these immunohistochemical markers are not widely available for use in community practice in the United States and in many parts of the world (at least not yet). Additionally, there are some problems in some of the immunohistochemical panels that have been used. For example, the protocols that have received the most attention utilize markers like CDX2 and CK20 to help establish intestinal lineage but several studies have recently shown that these markers can in fact be expressed, not uncommonly, by pancreatobiliary adenocarcinomas, as well as the pancreatobiliary-type ductules in this region, albeit often more focally.4, 7, 20, 21 This further complicates the commonly mixed/hybrid nature of ampullary tumors which has been highlighted as a frequent finding in some studies.22 Thus, it is not surprising that even with the most complex immunohistochemical panels devised to capture most cases4, 5 a significant proportion (18–39%) remain unclassifiable.4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 16, 17, 18, 19

While immunohistochemical protocols are being refined and verified for routine use, histomorphologic classification remains standard of care and is required by the College of American Pathologists’ protocols. While this classification appears in theory to be simple and logical, its reproducibility, prognostic relevance and applicability to routine practice have not been fully tested, with conflicting results in the literature.4, 7, 8, 9, 15, 16, 17, 18, 23

The purpose of this study was to verify the applicability and reproducibility of the morphologic classification of ampullary carcinomas and their clinical associations.

Materials and methods

The study was performed in accordance with the institutional review board requirements.

Case Selection

Among 1469 pancreatoduodenectomy specimens from the archives of the authors’ pathology departments, 249 consecutive, stringently defined cases of invasive ampullary carcinoma (with a frequency of 17%, similar to that of most major studies)24, 25, 26, 27 were culled.

Tumors were classified as ampullary carcinomas according to recently refined definitions.6 Briefly, if its epicenter was located in the ampulla/major papilla, and if it fulfilled one of the four recognized categories,6 which represents a modification of the four groups by the College of American Pathologists’ cancer synoptic protocol for ampullary tumors28, then it was classified as an ampullary cancer. If more than 75% of the tumor was away from the ampulla, it was regarded as non-ampullary. All non-ampullary cancers and other dubious cases were excluded from analysis.

Of the 249 cases, only 232 tumors had complete material and foci of invasion that were >3.0 mm available for evaluation and these were selected for histologic subtyping. The 3.0 mm cutoff was selected to allow for adequate appreciation of the tumors’ morphologic characteristics. Detailed anatomic site-specific classification as well as some of the other clinicopathologic associations of this cohort was the subject of a previously published study and the morphologic classification that was done in that study was performed by a single author (VA), and was not based on consensus.6

Cell Lineage Morphology Assessment

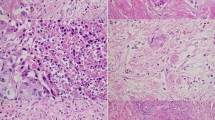

Five pathologists blindly and independently classified the 232 invasive ampullary adenocarcinomas based on their resemblance to pancreatic/biliary or colonic carcinomas in accordance with the criteria proposed by Kimura et al2 and endorsed by Albores-Saavedra et al1 for ampullary carcinomas (Figure 1). The observers were from variable backgrounds (one fellow, one GI fellowship-trained, three generalist/oncologic pathologists), all trained at different institutions and all working at different institutions at the time of the study, but all with interest/expertise in pancreatobiliary/gastrointestinal and ampullary pathology.

(a) Ampullary carcinoma with intestinal features. Note the presence of large tubules lined by tall columnar cells with elongated, pseudostratified, hyperchromatic nuclei resembling colonic-type adenocarcinoma. Luminal necrotic debris and acute inflammatory cells are also present. (b) Ampullary carcinoma with pancreatobiliary features. Small widely separated glands are lined by low cuboidal eosinophilic epithelium with a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, and round nuclei with vesicular chromatin and irregular nuclear contours.

Observers were instructed to acknowledge even a small component of a different cell lineage in any area of the invasive carcinoma including at the tumor’s advancing edge. This was felt to be necessary and important, considering that the pancreatobiliary versus intestinal classification is now also advocated (and in fact, expected by oncologists) even for ampullary biopsies, and moreover, several immunohistochemical studies on this topic are based on tissue microarrays.5, 8, 9, 13, 14, 29

Accordingly, in a ‘purist approach’ the observers were asked to classify each case into one of four categories as pure-intestinal, pure-pancreatobiliary, mixed pancreatobiliary-intestinal, or other (non-tubular (non-gland forming) adenocarcinoma; signet ring cell, neuroendocrine, undifferentiated, mucinous, and undetermined/unclassified cases that did not fit into any of the aforementioned three categories).

Separately, a forced-binary approach was then also applied for the mixed category of cases, where observers were asked to place the cases that they classified as ‘mixed pancreatobiliary-intestinal’ into either intestinal-predominant, pancreatobiliary-predominant, or predominantly non-glandular categories (Table 1). This also applied to the ‘other’ category in that if the tumors showed predominant pancreatobiliary or intestinal tubular pattern, they were to be placed into the corresponding pancreatobiliary- or intestinal-predominant category.

For the purposes of correlation with clinicopathologic findings and clinical outcome, three of five agreements were considered a consensus diagnosis (Table 2).

After blinded review, the cases were re-analyzed by the observers as a group in an attempt to determine potential reasons or explanations for lack of concordance in classification.

Evaluation of Clinicopathologic Associations

Information on the patients’ demographics, clinical presentation, and follow-up were obtained through pathology databases, patients’ charts, and/or by contacting the patients’ primary physicians.

Histologic grade, lymph-vascular, and perineural invasion, as well as lymph node and resection margin status were verified by histologic examination. Site-specific classification of the tumors as ampullary-duodenal, intra-ampullary papillary tubular neoplasm (IAPN)-associated, ampullary-ductal and ampullary-NOS (papilla of Vater) was performed as previously outlined.6 Tumor budding was also measured and classified as low and high by using criteria previously outlined by Ohike et al.30

The study was not controlled for patient treatment/management. However, there was also no known treatment bias employed in patient management.

Comparison of Pancreatobiliary-Predominant Group with Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinomas

The survival of the pancreatobiliary-predominant group of ampullary carcinomas was contrasted with a previously unpublished, cohort of 476 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (pancreatobiliary-type carcinomas of pancreatic origin) from the authors’ database.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data analyses were performed by calculating frequency and percentage for categorical variables, or measures of central tendency (means or medians) for continuous variables. After having checked for the normality assumption, the univariate analyses of continuous variables were done by one way analysis of variance or Kruskal Wallis tests, where it is appropriate. Tukey HSD or Conover-Dunn tests were also used for multiple comparisons. For the univariate analyses of categorical variables, χ2 tests were performed. Survival analyses examined factors associated with post-diagnosis mortality. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were constructed with corresponding log-rank tests for statistical significance to examine survival based on a variety of demographic and disease-related characteristics. Cox proportional hazards models and extended Cox models were utilized to estimate univariate and multivariate survival, when the proportional hazards assumption was violated, to examine the association between survival and a variety of factors taken together. Survival analysis results were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) and reported with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Proportional hazard assumptions were tested by examining log minus log plots for each variable in the model. In addition, all models were examined for interactions and multicolinearity among covariates. For all tests a two-sided P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Interobserver agreement was evaluated by Cohen’s κ and was categorized as poor (κ<0.20), fair (0.21<κ<0.40), moderate (0.41<κ<0.60), substantial (0.61<κ<0.80), or almost perfect (κ>0.80). Unity (κ 1) represents perfect agreement, indicating that observers agreed in their classification of every case, while κ of 0 suggests agreement no better than that expected by chance.

Results

Clinical Characteristics

For this cohort of 232 ampullary carcinomas with invasive component>3.0 mm available for examination, the mean patient age was 65 years (range: 27–88 years) with a male to female ratio of 1.5:1. The mean tumor size was 2.6 cm (range 0.7–8.0 cm). Pathologic T-stage distribution was as follows: T1/T2/T3/T4, n=58/86/83/5, respectively, with 40% of patients showing lymph node metastasis.

Histologic analysis # 1

There were 194 (84%) tubular (gland forming) carcinomas and 38 (16%) non-tubular or ‘other’ types of carcinoma. Using the ‘purist’ approach to classification (with the cases classified as pure-intestinal, pure-pancreatobiliary, mixed pancreatobiliary-intestinal, or other) the degree of interobserver agreement of the morphologic classification system was ‘fair’ (κ=0.39; z=28.80; P<0.001). There was full agreement by all observers (5/5) in 53 cases (23%). Utilizing three of five agreements as consensus the frequencies of the four subtypes were as follows: Mixed pancreatobiliary-intestinal was the most common category (n=94, 40%), followed by pure-pancreatobiliary (n=74, 32%), other (n=51, 22%), and pure-intestinal (n=13, 6%) (Table 2).

Histologic analysis # 2

This analysis was performed by incorporating the results of the forced-binary approach with each mixed case (and if applicable, ‘other’ cases) being classified as either mixed-intestinal or mixed pancreatobiliary based on the favored overall/predominant pattern. For analysis, the mixed-intestinal cases were grouped together with the pure-intestinal cases as intestinal-predominant, while the pure-pancreatobiliary and mixed pancreatobiliary cases were grouped together as pancreatobiliary-predominant. The level of interobserver agreement with this re-grouping improved to ‘moderate’ (κ=0.44; z=28.09; P<0.0001) and the agreement between observers increased to 81 cases (35%). Utilizing three of five agreements as consensus the frequencies of the three subtypes were as follows: pancreatobiliary-predominant group (n=137, 59%), intestinal-predominant group (n=57, 25%), followed by the other group (n=38, 16%) (Table 2).

Reasons for Discrepancies

In discussions held among the observers in order to elicit possible reasons for discrepancies, the following issues were elucidated: Of the mixed pancreatobiliary-intestinal tumors (n=94), some cases showed transformative features characterized by a transition from intestinal-type epithelium on the one hand to pancreatobiliary-type epithelium, the latter sometimes detected at the leading edge of the invasive focus. Occasional mixed pancreatobiliary-intestinal cases also showed a composite pattern in the central part (and not the advancing edge) of the tumor with very distinct intestinal and pancreatobiliary patterns, but without predominance of any one component (Figure 2); in others, the lining epithelium of the glands appeared to have chimeric features, that is, some features were attributable to intestinal and others to pancreatobiliary type morphology (Figure 3).

A case of ampullary carcinoma with morphologic heterogeneity (mixed pancreatobiliary and intestinal features). (a) Glands show mixed morphologic patterns with intestinal-type units (right side of the image) lined by tall columnar cells with pseudostratified nuclei, and more smaller pancreatobiliary glands lined by low cuboidal eosinophilic epithelium with a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, and no nuclear elongation or pseudostratification (center and upper left). (b) Higher power view of the more pancreatobiliary-type glands within the center of the same tumor. (c) Higher power view of the more intestinal glands in the same case.

Different areas of a case of ampullary carcinoma with mixed pancreatobiliary and intestinal features illustrated at different magnifications (a and c, low power and b and d, higher power). These images were shown blindly to eight observers (five faculty and three fellows) and image (c) was classified as pancreatobiliary by 6/8 and hybrid by 2/8 while image (d) was classified as intestinal by 4/8 and mixed by 4/8).

Correlation of Morphologic Patterns with Clinicopathologic Characteristics

Purist’s pattern groups

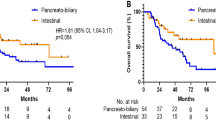

Utilizing the consensus diagnosis (3/5 agreement) in the purist’s approach diagnoses (pure-pancreatobiliary, pure-intestinal, and mixed pancreatobiliary-intestinal), the comparison of clinicopathologic characteristics revealed that pure-intestinal-type tumors were largest (4.5 cm) compared with mixed pancreatobiliary-intestinal (2.7 cm) and pure-pancreatobiliary type (2.2 cm), and this was statistically significant (P<0.001). The median survival of the pure-intestinal type was longer than the pure-pancreatobiliary type, 80 versus 40 months, but this was not statistically significant (P=0.33) nor was the difference between pure-pancreatobiliary, mixed pancreatobiliary-intestinal, and pure-intestinal types (40 versus 56 versus 80 months, P=0.65) (Figure 4). All other clinicopathologic characteristics (including nodal status, T stage, as well as 3- and 5-year survival rates) were also not statistically significant (Table 3). At the same time, it was noted that the features of the mixed tumors fell between pure-intestinal and pure-pancreatobiliary tumors in all characteristics including survival; however the median survival (56 months) was closer to that of pure-pancreatobiliary tumors (40 months) than pure-intestinal tumors (80 months). The ‘others’ category was disregarded for this analysis.

(a) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for pure-intestinal (INT), pure-pancreatobiliary (PB), and mixed-type ampullary carcinoma (AC) show no statistically significant difference in survival between the three groups. (b) Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing that pancreatobiliary-predominant ampullary carcinoma patients had shorter survival than their intestinal-predominant counterparts. (c) Kaplan–Meier survival curves also show that patients with pancreatobiliary-type pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) have significantly shorter survival than patients with pancreatobiliary-predominant ampullary carcinoma.

Predominant pattern groups

On comparison of clinicopathologic characteristics of the consensus diagnosis based on the forced-binary approach (dividing the mixed pancreatobiliary-intestinal cases into pancreatobiliary-predominant or intestinal-predominant groups), multiple clinicopathologic characteristics were found to have a statistically significant association (Table 4). Although pancreatobiliary-predominant tumors were smaller than the intestinal-predominant ones (mean 2.2 versus 3.6 cm) they had a higher pathologic T (pT3+T4) stage at diagnosis (39% versus 21%, P<0.05) and significantly shorter median survival of 41 versus 80 months (P=0.026), shorter 3-year survival of 55% versus 75% (P<0.05), and shorter 5-year survival of 38% versus 57% (P<0.05) (Table 4 and Figure 4) with a 1.78 times higher risk of death (95% CI: 1.06–2.98, P=0.028).

In multivariate analysis, while high tumor budding, high T stage, and lymph node positivity remained independent prognostic factors (P<0.05, respectively), histologic classification based on predominant histologic type (pancreatobiliary versus intestinal) failed to attain significance as an independent factor (P=0.39).

Comparison of Ampullary Carcinoma with Conventional Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

When the pancreatobiliary-predominant invasive ampullary carcinomas (n=137) were compared with a well-characterized cohort of pancreatobiliary-type carcinomas of pancreatic ductal origin (n=476), there was a statistically significant difference in survival between the two, with the pancreatic ones showing significantly shorter median overall survival (15.6 versus 41 months, P<0.001) than the pancreatobiliary-predominant ampullary carcinomas (Figure 4). This difference persisted even when size and lymph node status were matched (hazard ratio=1.97, 95% CI: 1.42–2.72, P<0.001).

Discussion

This study reveals that the reproducibility of the histology-based pancreatobiliary versus intestinal classification system1, 2 for invasive ampullary carcinomas in fact presents many challenges in daily practice, especially if intended to be applied for the stratification of individual patients to different (biologically defined) treatment protocols using a purist approach. First of all, the agreement between pathologists is only fair, with fewer than 25% of cases achieving uniform agreement by observers. More importantly, 40% of the ampullary carcinomas are designated as mixed. On critical analysis of the literature, this ‘heterogeneity’ is also amply demonstrated by immunohistochemical studies. This was one of the highlights in a recent study by Ang et al4 in which 18% of tumors were classified as ‘ambiguous’ despite complex immunohistochemical panels. While the study by Ang et al gives the impression that only 18% of cases were ‘ambiguous’, Ang’s cases were apparently not consecutive cases, but were ‘selected’ (David Klimstra, personal communication, 2016) and thus may/may not reflect the true frequency of unclassifiable cases. Preliminary results of cases studied by Costigan et al31 from Ireland revealed that 27% of cases were ‘ambiguous/unclassifiable’, while 8% were intestinal and 65% were pancreatobiliary with the Ang immunohistochemical panel. Additionally, in a study by Ohike et al22 more than 30% of invasive ampullary carcinomas in each category showed an unexpected, inverse immunoprofile. This is not surprising considering the transitional nature of this anatomic landmark, which is comprised of a variety of cell types, where even the normal constituent structures exhibit hybrid characteristics (eg, pancreatobiliary-type ducts on the ampullary wall often show CDX2 positivity). Accordingly, while conducting this study, it became clear that there is frequent and striking heterogeneity in the histologic phenotype of invasive ampullary carcinomas.

Histomorphologic classification of ampullary carcinomas is expected in every case and is a requirement by the College of American Pathologists’ synoptic reporting guidelines. Immunohistochemical support for this has promise but needs more detailed analysis. Interpretation of well-characterized antibodies may prove more objective than evaluating more subtle histopathologic parameters in many cases; however, the significance of that antibody expression, its correlation with cell lineage, and relationship to tumor biology are a totally different matter. Whether the markers used for this purpose will bring that kind of ‘objectivity’ to the classification of ampullary cancers is so far debatable as preliminary results by Costigan et al31 indicate. While these immunohistochemical panels are being perfected, and until they become more applicable worldwide, morphologic classification of ampullary carcinoma will likely remain the norm. This study will hopefully allow the community to appreciate that a significant proportion of these tumors has hybrid features, thus alleviating some of the misconceptions that recent immunohistochemistry-based publications have inadvertently caused. This confusion is understandable since many of these studies now claim that immunohistochemistry validates classification, and has prognostic significance. Some now mistakenly conclude that tumor typing is highly applicable and oncologists are now not only demanding the classification but expect a specific answer in each and every case, unwilling to accept that some cases may be unclassifiable. Meanwhile, our study has shown that 40% of ampullary carcinomas are in fact mixed/hybrid by morphology, a figure that is much higher than, admittedly, even we had expected.

When these discrepant and ‘mixed’ cases were re-analyzed to investigate possible reasons for the lack of clearcut agreement or distinction, it was elucidated that the hybrid nature of ampullary cancers can manifest in different ways; in some, this is attributable to different zones of the tumor exhibiting distinctive morphologic patterns, especially small tubular units with different cytomorphology within the tumor’s advancing edge. In others, the tumor cells within the same region (ie, same glands) appeared chimeric, showing some features resembling intestinal and others resembling more pancreatobiliary lineage. In such cases, depending on which criterion/feature an observer relied upon more heavily, the favored (predominant) pattern varied. Of note, the preinvasive component of even the pure-pancreatobiliary tumors often appears to be of intestinal phenotype as also previously noted in detail,22 and in fact, may be the reason why some recent publications have differing results.

Regardless of mechanism, this heterogeneity impedes the ability of pathologists to accurately classify these tumors in some cases, even on full-face tissue sections, a problem that is naturally compounded in small biopsies. For this reason, histologic typing of ampullary carcinomas in endoscopic or image-guided biopsies should be regarded as preliminary and is subject to change after examination of the entire tumor. Furthermore, the results of immunohistochemical studies that utilize tissue microarrays prepared from a limited amount of tumor cells ought to be evaluated with caution, and in fact, may have to be avoided if a more ‘complete’ picture of the tumor is intended. It should be noted here that tissue microarray-based studies also suffer from the challenge of determining whether the fragment being analyzed represents a preinvasive or invasive tumor component. Some of the advocated immunohistochemical panels are proving complex and expensive and may not have the presumed prognostic value (unpublished personal data). For example, some of the clinician-driven studies including those by Schueneman et al13 (a microarray-based study) and Chang et al5 appeared to have included in situ carcinomas and adenomas in their analysis. Hence, it is not surprising that the latter studies give the impression of a prognostic correlation since most adenomas are CDX2+/MUC1− and have a much better prognosis than invasive carcinomas. Our main aim in this study was to assess the applicability and reproducibility of morphologic classification of ampullary carcinoma for the purposes of current daily practice and future studies that will attempt to use this classification as the basis to develop more discriminatory immunohistochemical panels. In fact, in this study, during the selection of cases for analysis, it became clear that distinguishing preinvasive from invasive neoplasms in the ampulla can be very challenging, with mimicry both ways, as has been previously highlighted by others.32 This phenomenon (preinvasive and invasive components often showing different phenotypes)22 may have also influenced the results of some studies.5, 8, 9, 19

While our study highlights several challenges in the applicability of histologic typing of ampullary carcinomas as pure-intestinal or pure-pancreatobiliary in routine practice, it also illustrates, based on the analysis of diagnoses rendered by the forced-binary approach, that as a general group, intestinal-predominant tumors have different characteristics from ‘pancreatobiliary-predominant’ tumors, which is in accordance with the impression in the literature.4, 5, 6, 11, 12, 13, 14, 17, 18, 19, 33, 34, 35 Pure-intestinal or intestinal-predominant ampullary carcinomas were significantly larger than their pancreatobiliary counterparts, but despite this, were less aggressive (with a tendency for lower stage disease, lower rates of nodal metastasis, and longer overall survival) than pure-pancreatobiliary or pancreatobiliary-predominant-type tumors, and almost double 5-year survival rate (38 versus 57%). However, on multivariate analysis this was not independent of other conventional pathologic parameters. In daily clinical practice one should be mindful that although the general characteristics of the groups differ significantly, this unfortunately does not mean that it is applicable to individual cases especially considering it is not independent prognostically.

Interestingly, our cohort showed a relatively high frequency of pancreatobiliary-predominant cases, which is one reason we felt obliged to compare our cohort with pancreatic adenocarcinomas, and found that even the pancreatobiliary-predominant ampullary carcinomas had a much better prognosis than pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Nevertheless, the high frequency of the ‘pancreatobiliary’ type raises the question of possible bias in our criteria for histologic classification. Considering that all five observers at the time of this study had already trained and were working at different institutions this seems an unlikely contributor. One potential bias in our study may be the fact that all five observers had an interest in pancreatobiliary pathology and may thus have been prone to recognizing histologic patterns as ‘pancreatobiliary’. However, these same observers were also heavily involved in, and exposed to, lower gastrointestinal tract pathology as well. Lastly, populational differences in the frequency of the pancreatobiliary-predominant pattern may account for differences in our cohort versus others. On the other hand, Costigan et al31 from Ireland recently noted a similarly higher rate of pancreatobiliary-type ampullary carcinomas (65 and 50% by immunohistochemistry and histomorphology, respectively) in their cohort.31 Analysis of larger cohorts with proper pathologic verification by multiple observers is required to better explain these differences.

The fact that the distinction between pancreatobiliary and intestinal-type ampullary carcinoma is fraught with challenges has significant implications for clinical management. Oncologists are now demanding that pathologists classify these tumors as such, and based on pathologic diagnoses will use gemcitabine-based treatment regimens for pancreatobiliary-type tumors and fluorouracil-based ones for intestinal-type tumors, often with conflicting or disappointing results.36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 In the meantime, careful scrutiny of the literature suggests that the recently devised immunohistochemical panels in fact show vastly conflicting results,4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 21, 33 presumably a magnified reflection of the imperfections of morphologic classification as elucidated in this study. This is now also being observed in molecular studies, which have shown overlapping molecular alterations even in seemingly ‘unambiguous’ cases.29, 42, 43 Nonetheless, we believe that in each case an attempt should be made to determine the predominant/favored histologic type and advocate diagnosing such cases, for example, as ‘invasive ampullary adenocarcinoma, tubular type, with mixed/hybrid pattern, predominantly with pancreatobiliary or intestinal-type features’. Of note, we do not currently officially incorporate immunohistochemistry results in our classification.

This study also demonstrates the importance of classifying ampullary cancers separately from pancreatic carcinomas. Several studies on this topic suggest that in periampullary tumors the site of origin (pancreatic or ampullary) is not a significant prognostic predictor, and that histologic tumor typing alone (as pancreatobiliary versus intestinal) may suffice.14, 33, 35, 44 Some authors have even questioned whether ampullary carcinoma should even be regarded as a separate entity when classifying these tumors.23, 35 Our study documents, firstly, that the pancreatobiliary variant of ampullary cancers are seldom pure (unlike pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and common bile duct carcinomas which are almost always pure), and second, and far more importantly, even the pancreatobiliary-type ampullary cancers have a much better prognosis than pancreatobiliary carcinomas arising in the pancreas. Thus, histologic typing and primary site of the tumor ought to be evaluated and reported separately.

In conclusion, as a transitional region, carcinomas of the ampulla often show hybrid phenotypes between pancreatobiliary and intestinal epithelium, which cause substantial subjectivity in their histologic designation. Mixed carcinomas with intratumoral heterogeneity are a frequent finding. If morphologic classification is done based on a predominant pattern approach, the histologic pancreatobiliary versus intestinal classification has moderate agreement, significant clinical associations, and a good prognostic value; however, the difference in survival is by no means analogous to that of pancreatic versus colonic adenocarcinoma. On the other hand, our findings also confirm that ampullary carcinomas should be distinguished from pancreatic ductal carcinomas, because even the pancreatobiliary-type ampullary cancers have a much better prognosis than pancreatic ones.

References

Albores-Saavedra J, Henson DE, Klimstra DS . Malignant epithelial tumors of the ampulla. In: Rosai J, Sobin L (eds). Atlas of Tumor Pathology: Tumors of the Gallbladder, Extrahepatic Bile Ducts, and Ampulla of Vater Vol. 27. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology: Washington, DC, 2000, pp 259–316.

Kimura W, Futakawa N, Yamagata S et al. Different clinicopathologic findings in two histologic types of carcinoma of papilla of Vater. Jpn J Cancer Res 1994;85: 161–166.

Adsay NV. Gallbladder, extrahepatic biliary tree, and ampulla. In: Mills SE (ed.). Sternberg's Diagnostic Surgical Pathology, 4th edn,Vol. 2. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, 2004, pp 1775–1828.

Ang DC, Shia J, Tang LH et al. The utility of immunohistochemistry in subtyping adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of vater. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38: 1371–1379.

Chang DK, Jamieson NB, Johns AL et al. Histomolecular phenotypes and outcome in adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of vater. J Clin Oncol 2013;31: 1348–1356.

Adsay V, Ohike N, Tajiri T et al. Ampullary region carcinomas: definition and site specific classification with delineation of four clinicopathologically and prognostically distinct subsets in an analysis of 249 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36: 1592–1608.

Chu PG, Schwarz RE, Lau SK et al. Immunohistochemical staining in the diagnosis of pancreatobiliary and ampulla of Vater adenocarcinoma: application of CDX2, CK17, MUC1, and MUC2. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29: 359–367.

Guo R, Overman M, Chatterjee D et al. Aberrant expression of p53, p21, cyclin D1, and Bcl2 and their clinicopathological correlation in ampullary adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol 2014;45: 1015–1023.

Hansel DE, Maitra A, Lin JW et al. Expression of the caudal-type homeodomain transcription factors CDX 1/2 and outcome in carcinomas of the ampulla of Vater. J Clin Oncol 2005;23: 1811–1818.

Howe JR, Klimstra DS, Moccia RD et al. Factors predictive of survival in ampullary carcinoma. Ann Surg 1998;228: 87–94.

Kumari N, Prabha K, Singh RK et al. Intestinal and pancreatobiliary differentiation in periampullary carcinoma: the role of immunohistochemistry. Hum Pathol 2013;44: 2213–2219.

Okano K, Oshima M, Yachida S et al. Factors predicting survival and pathological subtype in patients with ampullary adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol 2014;110: 156–162.

Schueneman A, Goggins M, Ensor J et al. Validation of histomolecular classification utilizing histological subtype, MUC1, and CDX2 for prognostication of resected ampullary adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 2015;113: 64–68.

Westgaard A, Tafjord S, Farstad IN et al. Pancreatobiliary versus intestinal histologic type of differentiation is an independent prognostic factor in resected periampullary adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 2008;8: 1–11.

Zhou H, Schaefer N, Wolff M et al. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: comparative histologic/immunohistochemical classification and follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28: 875–882.

Kawabata Y, Tanaka T, Nishisaka T et al. Cytokeratin 20 (CK20) and apomucin 1 (MUC1) expression in ampullary carcinoma: correlation with tumor progression and prognosis. Diagn Pathol 2010;5: 75.

Morini S, Perrone G, Borzomati D et al. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: morphological and immunophenotypical classification predicts overall survival. Pancreas 2013;42: 60–66.

Moriya T, Kimura W, Hirai I et al. Expression of MUC1 and MUC2 in ampullary cancer. Int J Surg Pathol 2011;19: 441–447.

Westgaard A, Schjolberg AR, Cvancarova M et al. Differentiation markers in pancreatic head adenocarcinomas: MUC1 and MUC4 expression indicates poor prognosis in pancreatobiliary differentiated tumours. Histopathology 2009;54: 337–347.

Xiao W, Hong H, Awadallah A et al. Utilization of CDX2 expression in diagnosing pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and predicting prognosis. PLoS One 2014;9: e86853.

Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immunohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27: 303–310.

Ohike N, Kim GE, Tajiri T et al. Intra-ampullary papillary-tubular neoplasm (IAPN): characterization of tumoral intraepithelial neoplasia occurring within the ampulla: a clinicopathologic analysis of 82 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34: 1731–1748.

Perysinakis I, Margaris I, Kouraklis G . Ampullary cancer—a separate clinical entity? Histopathology 2014;64: 759–768.

Fernandez-del Castillo C, Morales-Oyarvide V, McGrath D et al. Evolution of the Whipple procedure at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Surgery 2012;152: S56–S63.

He J, Ahuja N, Makary MA et al. 2564 resected periampullary adenocarcinomas at a single institution: trends over three decades. HPB (Oxford) 2014;16: 83–90.

Kim KJ, Choi DW, Kim WS et al. Adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: predictors of survival and recurrence after curative radical resection. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2011;15: 171–178.

Klein F, Jacob D, Bahra M et al. Prognostic factors for long-term survival in patients with ampullary carcinoma: the results of a 15-year observation period after pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB Surg 2014;2014: 970234.

Washington K, Berlin J, Branton P et al. CAP Protocol for the Examination of Specimens from Patients with Carcinoma of the Ampulla of Vater. 2012. http://www.cap.org/ShowProperty?nodePath=/UCMCon/ContributionFolders/WebContent/pdf/ampulla-12protocol-3101.pdf. (Accessed: 17 November 2015).

Overman MJ, Zhang J, Kopetz S et al. Gene expression profiling of ampullary carcinomas classifies ampullary carcinomas into biliary-like and intestinal-like subtypes that are prognostic of outcome. PLoS One 2013;8: e65144.

Ohike N, Coban I, Kim GE et al. Tumor budding as a strong prognostic indicator in invasive ampullary adenocarcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34: 1417–1424.

Costigan D, Sheahan K, Conlon KC et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in subtyping ampullary adenocarcinoma (Abstract). Mod Pathol 2016;29: 167A.

Bellizzi AM, Kahaleh M, Stelow EB . The assessment of specimens procured by endoscopic ampullectomy. Am J Clin Pathol 2009;132: 506–513.

Bronsert P, Kohler I, Werner M et al. Intestinal-type of differentiation predicts favourable overall survival: confirmatory clinicopathological analysis of 198 periampullary adenocarcinomas of pancreatic, biliary, ampullary and duodenal origin. BMC Cancer 2013;13: 428.

Pomianowska E, Grzyb K, Westgaard A et al. Reclassification of tumour origin in resected periampullary adenocarcinomas reveals underestimation of distal bile duct cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2012;38: 1043–1050.

Westgaard A, Pomianowska E, Clausen OP et al. Intestinal-type and pancreatobiliary-type adenocarcinomas: how does ampullary carcinoma differ from other periampullary malignancies? Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20: 430–439.

Neoptolemos JP, Moore MJ, Cox TF et al. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid or gemcitabine vs observation on survival in patients with resected periampullary adenocarcinoma: the ESPAC-3 periampullary cancer randomized trial. JAMA 2012;308: 147–156.

Bhatia S, Miller RC, Haddock MG et al. Adjuvant therapy for ampullary carcinomas: the Mayo Clinic experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;66: 514–519.

Lee JH, Whittington R, Williams NN et al. Outcome of pancreaticoduodenectomy and impact of adjuvant therapy for ampullary carcinomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;47: 945–953.

Zhou J, Hsu CC, Winter JM et al. Adjuvant chemoradiation versus surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Radiother Oncol 2009;92: 244–248.

Sikora SS, Balachandran P, Dimri K et al. Adjuvant chemo-radiotherapy in ampullary cancers. Eur J Surg Oncol 2005;31: 158–163.

Jiang ZQ, Varadhachary G, Wang X et al. A retrospective study of ampullary adenocarcinomas: overall survival and responsiveness to fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2013;24: 2349–2353.

Hechtman JF, Liu W, Sadowska J et al. Sequencing of 279 cancer genes in ampullary carcinoma reveals trends relating to histologic subtypes and frequent amplification and overexpression of ERBB2 (HER2). Mod Pathol 2015;28: 1123–1129.

Watanabe M, Asaka M, Tanaka J et al. Point mutation of K-ras gene codon 12 in biliary tract tumors. Gastroenterology 1994;107: 1147–1153.

Schirmacher P, Buchler MW . Ampullary adenocarcinoma—differentiation matters. BMC Cancer 2008;8: 251.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reid, M., Balci, S., Ohike, N. et al. Ampullary carcinoma is often of mixed or hybrid histologic type: an analysis of reproducibility and clinical relevance of classification as pancreatobiliary versus intestinal in 232 cases. Mod Pathol 29, 1575–1585 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.124

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.124

This article is cited by

-

Variabilities in global DNA methylation and β-sheet richness establish spectroscopic landscapes among subtypes of pancreatic cancer

European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (2023)

-

Novel method for evaluating the indication for endoscopic papillectomy in patients with ampullary adenocarcinoma

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Endoscopic Papillectomy for Ampullary Adenomas: Different Outcomes in Sporadic Tumors and Those Associated with Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery (2021)

-

APC mutations are common in adenomas but infrequent in adenocarcinomas of the non-ampullary duodenum

Journal of Gastroenterology (2021)

-

Can we classify ampullary tumours better? Clinical, pathological and molecular features. Results of an AGEO study

British Journal of Cancer (2019)