Abstract

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) is a transcription factor with a well-described oncogenic role. Study for each of five NF-κB pathway subunits was only reported on small cohorts in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). In this large cohort (n=533) of patients with de novo DLBCL, we evaluated the protein expression frequency, gene expression signature, and clinical implication for each of these five NF-κB subunits. Expression of p50, p52, p65, RELB, and c-Rel was 34%, 12%, 20%, 14%, and 23%, whereas p50/p65, p50/c-Rel, and p52/RELB expression was 11%, 11%, and 3%, respectively. NF-κB subunits were expressed in both germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) and activated B-cell-like (ABC) DLBCL, but p50 and p50/c-Rel were associated with ABC-DLBCL. p52, RELB, and p52/RELB expressions were associated with CD30 expression. p52 expression was negatively associated with BCL2 (B-cell lymphoma 2) expression and BCL2 rearrangement. Although p52 expression was associated with better progression-free survival (PFS) (P=0.0170), singular expression of the remaining NF-κB subunits alone did not show significant prognostic impact in the overall DLBCL cohort. Expression of p52/RELB was associated with better overall survival (OS) and PFS (P=0.0307 and P=0.0247). When cases were stratified into GCB- and ABC-DLBCL, p52 or p52/RELB dimer expression status was associated with better OS and PFS (P=0.0134 and P=0.0124) only within the GCB subtype. However, multivariate analysis did not show p52 expression to be an independent prognostic factor. Beneficial effect of p52 in GCB-DLBC appears to be its positive correlation with CD30 and negative correlation with BCL2 expression. Gene expression profiling (GEP) showed that p52+ GCB-DLBCL was distinct from p52− GCB-DLBCL. Collectively, our data suggest that DLBCL patients with p52 expression might not benefit from therapy targeting the NF-κB pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) was first described as a transcription factor essential for immunoglobulin κ light-chain transcription in B lymphocytes in 1986.1 The oncogenic role of NF-κB has been well described.2 NF-κB is a homo- or heterodimer comprised of two of five possible subunits, p50, p52, p65 (RELA), RELB, and c-Rel (REL), which all share the Rel homology domain (RHD). The RHD is characterized by a DNA-binding domain, dimerization domain, and nuclear localization signal (NLS) polypeptide domain. The NLS domain contains a binding site for IκB (a transcription factor inhibitor). p105 and p100 are precursors of p50 and p52, respectively, and they have an IκB-like domain in the C terminus. Therefore, p105 and p100 act as inhibitors of NF-κB activity. p105 is constitutively processed to produce p50, but p100 is only processed upon stimulation to produce p52. p50 and p52 are class I molecules, characterized by a nuclear localization domain with no transcription activation domain (TAD). p65, RELB, and c-Rel are class II molecules with unique TADs in respective molecules. Owing to the lack of a TAD in class I molecules, a class II molecule is generally required to activate target gene expression. In a resting state, NF-κB dimers are sequestered by IκB proteins in the cytoplasm. Upon stimulation, IκB proteins are phosphorylated by the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, which is composed of IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ. IKKα and IKKβ have catalytic activity, and IKKγ (also known as NF-κB essential modulator, NEMO) has regulatory activity. In the classical (canonical) pathway, NEMO-dependent activation of IKKβ further phosphorylates IκBα so that phosphorylated IκBα is further ubiquitinated and degraded. In the alternative (noncanonical) pathway, a p100-RELB complex is processed by NEMO-independent IKKα homodimers to generate p52-RELB. The free NF-κB dimers translocate into the nucleus and activate target gene expression.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common lymphoid malignancy worldwide. It is a heterogeneous group of diseases with various morphological variants, immunohistochemical subgroups and subtypes.3, 4, 5 Using GEP, Alizadeh et al6 showed two molecularly distinct forms of DLBCL corresponding to the developmental stage of B lymphocytes-germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) DLBCL and activated B-cell-like (ABC) DLBCL.6 ABC-DLBCL is characterized by preferential activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway and nuclear expression of p50/p65 and p50/c-Rel dimers compared with GCB-DLBCL.7 The current standard therapy for DLBCL is rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP). Recently, therapeutic agents targeting NF-κB pathway are assessed as a front-line therapy. R-CHOP with bortezomib or lenalidomide with R-CHOP (R2CHOP) as a front-line therapy for DLBCL are currently ongoing in several clinical trials. Therefore, increasing demand for upfront testing of NF-κB would be expected. However, little data regarding expression of all NF-κB subunits in DLBCL and its clinical significance are available. Moreover, most previous studies have evaluated only a subset of the NF-κB subunits.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 There are only two studies using all five subunits in DLBCL-a cohort of 88 patients with DLBCL by Odqvist et al16 and a cohort of 45 patients with testicular DLBCL by Menter et al.17 In the current study, we evaluated expression of all five subunits of the NF-κB protein by immunohistochemistry and its clinical implications in a large cohort of patients with de novo DLBCL.

Materials and methods

Patient Selection

We studied a cohort of 533 patients with de novo DLBCL treated with R-CHOP or R-CHOP-like therapy, collected as part of the International DLBCL Rituximab-CHOP Consortium Program Study.18, 19 All cases were classified following the World Health Organization classification criteria after review by a group of hematopathologists. Cases that were excluded from this study included: large-cell transformation from low-grade B-cell lymphoma, DLBCL associated with Epstein–Barr virus, immunodeficiency-associated lymphoproliferative disorders (especially human immunodeficiency virus infection), T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, and primary central nervous system DLBCL. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of all participating institutions. The overall study was approved by the IRB at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, USA. This study was conducted in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Tissue Microarray Immunohistochemical Studies for NF-κB Pathways and Subunits

Tumor-rich areas were selected for tissue microarray construction as described previously.18 Immunohistochemical studies for various markers were performed; NF-κB subunits (p52, p50, p65, RELB, and c-Rel), B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2), B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6), CD10, CD30, Forkhead box protein P1 (FOXP1), germinal center B-cell-expressed transcript-1 (GCET1), multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM1), MYC, and phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (pSTAT3). Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were used to determine a prognostically relevant cutoff with optimal sensitivity and specificity for each marker.18, 20 When an optimal cutoff value for an individual marker could not be determined by an ROC curve, a conventional cutoff value was decided based on reports in the literature. The cutoff scores for these markers used in this study were as follows: 20% for CD30 and p53; 30% for CD10 and BCL6; 40% for MYC; 50% for pSTAT3; 60% for GCET1, MUM1 and FOXP1; and 70% for BCL2. The cutoff values for NF-κB subunits were: p50, ≥20%; p52, ≥40%; p65, ≥30%;16 RELB, ≥10%; and c-Rel, ≥20%.

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization, TP53 Sequencing, and GEP

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis for MYC, BCL2, and BCL6 was performed as described previously.21 TP53 exon sequencing was performed and data were analyzed as described previously.22 RNA was extracted from 479 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue samples using HighPure Paraffin RNA Extraction Kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and subjected to GEP as described previously.18, 23 The CEL files are deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus repository (GSE#31312).18 Cell-of-origin (COO) classification was determined primarily based on GEP data and secondarily using immunohistochemical results and the Visco-Young algorithm.18 Hans classification has also been performed for comparison.24

Response Definitions and Statistical Analysis

Response assessment was standardized among different institutions following the criteria based on CT scan and bone marrow biopsy.25 Late deaths not related to the underlying lymphoma or its treatment were not considered treatment failures. Overall survival (OS) was defined from the date of diagnosis to the date of last follow-up or death. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined from the date of diagnosis to the date of progression or death. Survival probability was determined using the Kaplan–Meier method, with differences compared by the log-rank test. A Cox proportional-hazards model was used for univariate and multivariate analysis. Variables with P<0.05 (two-sided) were considered to be statistically significant. Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher’s exact test. GraphPad Prism V5 (La Jolla, CA, USA) and SPSS Statistics V21 (Armonk, NY, USA) were used for statistical analyses.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Three hundred and six (57%) patients were men and 227 (43%) were women. Two hundred and thirty (43%) patients were <60 years and 303 (57%) were ≥60 years of age. Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level was elevated in 304 (63%) patients and B symptoms were present in 154 (33%) patients. One hundred and thirty (33%) patients had bulky (≥6 cm) diseases and 114 (22%) patients had ≥2 extranodal sites of involvement. Two hundred and sixty-six (52%) patients had advanced stage (stages III and IV) disease. Seventy-two (16%) patients had a Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score ≥2 and 221 (42%) patients had an IPI ≥3. Four hundred seventy-one (88%) patients had either complete remission or partial remission. Two hundred eighty (54%) and 243 (46%) patients had GCB and ABC DLBCL, respectively. Ten patients were unclassifiable owing to the lack of GEP data and/or tissue exhaustion. Based on Hans classification,24 421 out of 488 (86.3%) available cases showed concordance compared with our result. Such observation has been found in several former and current publications.18, 21, 22, 24, 26, 27, 28

Expression of NF-κB Subunits in DLBCL

Nuclear expression with or without cytoplasmic expression of each marker in lymphoma cells was considered positive (Figure 1a). Excluding 36 cases with tissue exhaustion, a total of 278 (56%) cases expressed at least one of NF-κB subunits (Table 1). In detail, expression of single, 2, 3, and 4 subunits was seen in 147 (53%), 84 (30%), 38 (14%), and 9 (3%) cases, respectively. Cases with expression of all five subunits were not found. Overall, expression of p50, p52, p65, RELB, and c-Rel was observed in 150/443 (34%), 56/455 (12%), 92/461 (20%), 64/452 (14%), and 103/439 (23%) cases, respectively. p50 expression was found as single, 2, 3, and 4 subunits in 55 (37%), 55 (37%), 31 (21%), and 9 (6%) cases, respectively. p50/p65 (n=25) and p50/c-Rel (n=16) dimer expression were the predominant forms. Predilection for p65 and c-Rel in p50-expressing cases was seen in cases with three subunit expression (p50/p65/c-Rel, n=12). p52 expression was found as single, 2, 3, and 4 subunits in 15 (27%), 20 (36%), 16 (29%), and 5 (9%) cases, respectively. p50/p52 (n=8) and p52/c-Rel (n=7) were common forms and p52/RELB dimer was uncommon (n=3). p65 expression was found as single, 2, 3, and 4 subunits in 29 (32%), 35 (38%), 20 (22%), and 8 (9%) cases, respectively. Other than p50, dimerizing partners of p65 were scattered. RELB expression was found as single, 2, 3, and 4 subunits in 20 (31%), 20 (31%), 17 (27%), and 7 (11%) cases, respectively. RELB/c-Rel dimer (n=9) was the most common form. c-Rel expression was found as single, 2, 3, and 4 subunits in 28 (27%), 38 (37%), 30 (29%), and 7 (7%) cases, respectively. Two hundred and nineteen cases did not express any NF-κB subunits.

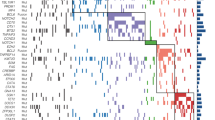

Expression of each nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) subunit. (a) Sheets of large atypical lymphoid cells, which is a typical appearance of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) × 600). Nuclear with or without cytoplasmic expression of each NF-κB subunit was considered positive (× 600). (b) Distribution of cell-of-origin with respect to expression of each NF-κB subunit. Two-sided P-value was calculated with Fisher’s exact test. ABC, activated B-cell-like; GCB, germinal center B-cell-like.

Clinical Features of DLBCL with Expression of NF-κB Subunits

We initially compared various clinical features between patients with and without expression of each NF-κB subunit (Table 2). Compared with DLBCL patients without p52 expression, p52+ DLBCL patients were younger (<60 years) (P=0.0089) and showed a significant trend of limited stage (P=0.0557). p65+ DLBCL patients were more commonly men (P=0.0091). Two or more sites of extranodal involvement were more commonly seen in c-Rel+ DLBCL patients (P=0.0022). The remaining clinical features were not significantly different between DLBCL patients with and without p52, p65, and c-Rel expression. There were no significantly different clinical parameters with respect to p50 and RELB expression in DLBCL. Clinical implications of common NF-κB dimers (p50/p65, p50/c-Rel, and p52/RELB) were also evaluated. Compared with DLBCL without p52/RELB expression, p52+/RELB+ DLBCL patients were younger (<60 years) and had stage I or II disease (P=0.0180 and P=0.0156, respectively). The remaining clinical features were not significantly different between DLBCL patients with and without p52/RELB expression. There were no significantly different clinical parameters with respect to p50/65 or p50/c-Rel dimer expression in patients with DLBCL.

COO Classification, Protein Expression, and Genetic Features of NF-κB Subunits

Expression of p50, p52, p65, RELB, and c-Rel was observed in 23%, 13%, 20%, 11%, and 18% of GCB DLBCL, respectively, and in 35%, 9%, 15%, 13%, and 22% of ABC DLBCL, respectively (Figure 1b). Expression of p50/p65, p50/c-Rel, and p52/RELB was observed in 9%, 7%, and 3% of GCB DLBCL and in 9%, 12%, and 2% of ABC DLBCL, respectively. p50 expression and p50/c-Rel dimer expression were correlated with the ABC subtype (P=0.0088 and 0.0380, respectively) (Table 3). No other NF-κB subunits or dimers were correlated with COO classification. CD30 expression was more frequently observed in p52+, RELB+, and p52+/RELB+ DLBCLs compared with DLBCL negative for these proteins (P<0.0001, P=0.0067, and P<0.0001, respectively) (Figure 2a). BCL2 expression was less common in p52+ DLBCL (P=0.0073) (Figure 2b). MYC expression was less frequently observed in DLBCL with c-Rel and p50/c-Rel expression (P=0.0003 and P=0.0030, respectively). BCL2 was less frequently rearranged in p50+ and p52+ DLBCL compared with cases without p50 and p52 expression, respectively (P=0.0080 and P=0.0173, respectively) (Figure 2c). There were no differences in expression of pSTAT3 and BCL6, rearrangements of the BCL6 and MYC genes, p53 expression, TP53 deletion, and TP53 mutations with respect to expression of NF-κB subunits (Table 3).

Expression of NF-κB Subunits and Survival

Except that expression of p52 correlated with better PFS (P=0.0170) and a trend of better OS (P=0.0549) (Figure 3), expression of NF-κB subunits was not associated with significant differences in OS and PFS in the entire cohort. Survival analysis was also conducted with stratification of GCB- and ABC-DLBCLs. In GCB-DLBCL, cases with p52 expression had longer OS (P=0.0134) and PFS (P=0.0124). To the contrary, in ABC-DLBCL, cases with p52 expression were not associated with any significant differences in OS and PFS.

We also evaluated the potential clinical impact of common NF-κB dimers (Figure 4). The p52/RELB dimer expression in DLBCL was associated with better OS (P=0.0307) and PFS (P=0.0247). p52/RELB dimer expression status was associated with a significant trend towards better outcome only within the GCB subtype (OS and PFS, P=0.0687 and P=0.1276, respectively). The p50/p65 and p50/c-Rel dimer expression did not show significant differences in OS or PFS among all cases or after stratification of GCB/ABC (data not shown).

In univariate analysis, age (>60 years), presence of B symptoms, elevated serum LDH, advanced (III/IV) stage, ECOG ≥2 and ≥2 sites of extranodal involvement were associated with increased hazard ratio and expression of p52 was associated with decreased hazard ratio in GCB-DLBCL. However, in multivariate analysis, p52 expression was not identified as independent prognostic marker in GCB-DLBCL (P=0.191) (Table 4).

Gene Expression Profiling

We compared the GEP signatures in p52+ and p52− GCB-DLBCL (Figure 5). With an FDR threshold of 0.01, 103 genes were differentially expressed between the two groups. In p52+ GCB-DLBCL, 87 genes and 16 genes were up- and downregulated, respectively. Among the upregulated genes, LRRFIP1, NCOR2, FOXO3, BAP1, CFLAR, DUSP4, SAMSN1, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-F, and HLA-G were significant. LRRFIP1 is a transcriptional repressor and can regulate the expression of EGFR.29 NCOR2 is a nuclear receptor corepressor that mediates transcriptional silencing of target genes.30 FOXO3 may trigger apoptosis through the expression of genes necessary for cell death.31 DUSP4 negatively regulates mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs).32 SAMSN1 functions like a tumor suppressor gene in lung cancer.33 Increased expression of HLA class I molecules, including HLA-B, -C, -F, and -G, might induce an antitumor immune reaction. RBAK and BBX were noteworthy in the group of downregulated genes. RBAK encodes retinoblastoma-associated Krüppel protein, which activates androgen receptor-mediated transcription.34 BBX encodes a transcription factor that is necessary for G1- to S-phase cell cycle progression.35

Discussion

Immunohistochemical analysis for NF-κB subunits is a rapid and specific method to detect NF-κB pathway activation in DLBCL.8 Although several groups have shown NF-κB expression in DLBCL, many of these studies have lacked cutoff values for respective NF-κB proteins or did not study all five subunits. More importantly, they did not specifically exclude cases with infection by Epstein–Barr virus, which is known to activate the NF-κB pathway26 or had relatively small cohort of patients.16 In this study, expression of p50, p52, p65, RELB, and c-Rel was observed in 34%, 12%, 20%, 14% and 23% of patients, respectively, and expression of p50/p65, p50/c-Rel and p52/RELB dimers was seen in 11%, 11% and 3% of patients, respectively. These data are similar to that reported by Odqvist and Co-workers16 who used similar cutoffs, except that the expression frequency of class II molecules showed significant differences. The variations might have resulted from a difference in the fixation procedure because we used identical antibodies (p50, rabbit polyclonal antibody (GeneTex, Irvine, CA, USA); p52, mouse monoclonal antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA); p65, mouse monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); RELB, rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); and c-Rel, rabbit polyclonal antibody (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany)) to those used by Odqvist et al.16 With a cutoff value of 30%, Compagno et al showed that about 30% of GCB-DLBCL and 60% of ABC-DLBCL had nuclear expression of NF-κB subunits (either p50 or p52) by immunohistochemistry using rabbit monoclonal antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA).8 In our cohort, 36% of GCB-DLBCL and 43% of ABC-DLBCL expressed either p50 or p52, which are similar to their results in GCB-DLBCL (30%) but slightly lower in ABC-DLBCL (43%). We speculate that this difference may be partially due to the different antibodies. Irrespective of the difference in expression frequency, we confirmed the expression of NF-κB subunits in ABC-DLBCL as well as in GCB-DLBCL. Although constitutive activation of NF-κB is a hallmark of ABC-DLBCL, several groups have shown that NF-κB is also activated in a subset of GCB DLBCLs.8, 10, 16 Our data, combined with others, suggests that activation of the NF-κB pathway is not limited to ABC-DLBCL. We also found 23 cases with coexpression of p50 and p52, suggesting that activation of the classical and alternative pathways are not mutually exclusive in DLBCL.

Although expression of NF-κB proteins was observed in GCB-DLBCL, no specific subunit expression was correlated with the GCB subtype. Instead, p50 single and p50/c-Rel dimer expression correlated with ABC-DLBCL (Table 3), illustrating activation of the classical NF-κB pathway in that subtype. Not surprisingly, when NF-κB subunits were expressed in DLBCL, expression of two or more subunits was more common than single subunit expression. In addition, we observed 46 DLBCLs with the expression of three or more subunits. Taken together, these results suggest functional redundancy and intrinsic complexity of the NF-κB pathway in DLBCL.

Interestingly, p52 expression was positively correlated with CD30 expression in DLBCL. CD30 expression was also correlated with RELB and p52/RELB expression (Figure 2a). Activation of the alternative NF-κB pathway by CD30 has been shown in Hodgkin lymphoma36 and anaplastic large-cell lymphoma,37 and our results could suggest crosstalk between the alternative NF-κB pathway and CD30 signaling in DLBCL. DLBCL with p52 expression negatively correlated with BCL2 expression and BCL2 rearrangement (Figures 2b and c). This result is somewhat surprising because the p52/RELB dimer has been shown to induce BCL2 promoter activity, resulting in increased BCL2 expression in breast cancer.38 However, this phenomenon might be context-specific and such data have not been reported in DLBCL.

An impact of NF-κB subunit expression on the prognosis of DLBCL has been reported infrequently. Curry et al15 showed a worse OS in patients with c-Rel+ GCB-DLBCL compared with that in patients with c-Rel− GCB-DLBCL.15 Espinosa et al reported better outcome in patients with phosphorylated p65+ DLBCL compared with that in patients with p65− DLBCL.9 However, patients in these two studies were treated with chemotherapy without rituximab. Odqvist et al reported a better outcome in c-Rel+ DLBCL compared with that in c-Rel- DLBCL among patients who had been treated with R-CHOP.16 However, in our cohort, no single NF-κB subunit had an impact on survival, except p52’s association with better PFS. When cases were stratified into GCB- and ABC-DLBCL, we showed that p52 expression in GCB-DLBCL conferred better outcome. As CD30 and BCL2 are known independent prognostic factors in DLBCL,27, 39 we controlled for each of those biomarkers and evaluated the effect of p52 expression on OS in GCB-DLBCL. When BCL2 was controlled, the beneficial effect of p52 expression remained in patients with DLBCL without BCL2 expression (P=0.0477), but only a trend toward a beneficial effect was observed in patients with DLBCL with BCL2 expression (P=0.2275). Similarly, improved OS was found in cases of DLBCL without CD30 expression (P=0.0137), but the beneficial effect was not observed in cases of DLBCL with CD30 expression (P=0.2773). Our data suggest that p52 expression does not overcome the deleterious prognostic impact of BCL2 in GCB DLBCL, but has a favorable prognostic effect on DLBCL cases without CD30 signaling.

Although we could not establish p52 as an independent prognostic factor in patients with GCB DLBCL, expression of p52 could represent a unique subset. GEP identified distinctions between p52+ GCB-DLBCL and p52− GCB-DLBCL. The genes that were significantly upregulated in p52+ GCB-DLBCL have roles in apoptosis, negative regulation of the MAPK pathway, transcriptional repression and downregulation of cell proliferation. Meanwhile, the downregulated genes have functions in transcriptional activation and cell cycle progression.

Numerous studies have shown the prosurvival and oncogenic potential of the NF-κB pathway in various cancers. Proapoptotic and antioncogenic functions of the NF-κB pathway, particularly in association with p53, has also been reported. It has been shown by Jacque et al that RELB inhibits cell proliferation in murine fibroblasts in a p53-dependent manner.40 Similarly, Schumm et al showed cooperation of p52 and p53 in the regulation of p53 target genes.41 Rocha et al showed that p52/Bcl-3, an activator of CCND1, is switched to p52/HDAC repressor by p53 in a human non-small-cell lung cancer cell line.42 However, we did not observe any correlation between p52 expression and enhanced expression of p53. We also evaluated the effect of p52 on survival in TP53-mutated and TP53-wild-type GCB-DLBCL, and we observed a trend of better outcome in p52+ cases (P=0.0678 and P=0.0897, respectively). Our result suggests that p52 and TP53/p53 are not associated in GCB-DLBCL.

In summary, we identified a subset of GCB-DLBCL with superior outcome when expressing p52. p52 expression in GCB DLBCL was positively associated with CD30 expression and negatively associated with BCL2 expression and BCL2 rearrangement. However, p52 expression was not found to be an independent prognostic factor by multivariate analysis. Nevertheless, p52+ GCB-DLBCL is molecularly distinct from p52− GCB-DLBCL. Therapeutic agents targeting the NF-κB pathway have been introduced into the therapeutic regimen of patients with DLBCLs, and it is important to identify groups of patients for whom such therapy might be most appropriate or patient subsets who might not benefit.43, 44

References

Sen R, Baltimore D . Multiple nuclear factors interact with the immunoglobulin enhancer sequences. Cell 1986;46:705–716.

Basseres DS, Baldwin AS . Nuclear factor-kappaB and inhibitor of kappaB kinase pathways in oncogenic initiation and progression. Oncogene 2006;25:6817–6830.

Young KH, Medeiros LJ, Chan WC. Diffuse large B-cell lymphom. In: Orazi A, Weiss LM, Foucar K, Knowles DM (eds). Knowles' Neoplastic Hematopathology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013, pp 502–565.

Stein H, Warnke RA, Chan WC et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL et al (eds). WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th (edn) IARC: Lyon, France, 2008, pp 233–237.

Testoni M, Zucca E, Young KH, Bertoni F . Genetic lesions in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1069–1080.

Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature 2000;403:503–511.

Davis RE, Brown KD, Siebenlist U, Staudt LM . Constitutive nuclear factor kappaB activity is required for survival of activated B cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphoma cells. J Exp Med 2001;194:1861–1874.

Compagno M, Lim WK, Grunn A et al. Mutations of multiple genes cause deregulation of NF-kappaB in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nature 2009;459:717–721.

Espinosa I, Briones J, Bordes R, et al. Activation of the NF-kappaB signalling pathway in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: clinical implications. Histopathology 2008;53:441–449.

Pham LV, Fu L, Tamayo AT et al. Constitutive BR3 receptor signaling in diffuse, large B-cell lymphomas stabilizes nuclear factor-kappaB-inducing kinase while activating both canonical and alternative nuclear factor-kappaB pathways. Blood 2011;117:200–210.

Bavi P, Uddin S, Bu R et al. The biological and clinical impact of inhibition of NF-kappaB-initiated apoptosis in diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL). J Pathol 2011;224:355–366.

Montes-Moreno S, Odqvist L, Diaz-Perez JA et al. EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly is an aggressive post-germinal center B-cell neoplasm characterized by prominent nuclear factor-kB activation. Mod Pathol 2012;25:968–982.

Hu CR, Wang JH, Wang R, Sun Q, Chen LB . Both FOXP1 and p65 expression are adverse risk factors in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a retrospective study in China. Acta Histochem 2013;115:137–143.

Shin HC, Seo J, Kang BW et al. Clinical significance of nuclear factor kappaB and chemokine receptor CXCR4 expression in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who received rituximab-based therapy. Korean J Intern Med 2014;29:785–792.

Curry CV, Ewton AA, Olsen RJ et al. Prognostic impact of C-REL expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Hematop 2009;2:20–26.

Odqvist L, Montes-Moreno S, Sanchez-Pacheco RE et al. NFkappaB expression is a feature of both activated B-cell-like and germinal center B-cell-like subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol 2014;27:1331–1337.

Menter T, Ernst M, Drachneris J et al. Phenotype profiling of primary testicular diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Hematol Oncol 2014;32:72–81.

Visco C, Li Y, Xu-Monette ZY et al. Comprehensive gene expression profiling and immunohistochemical studies support application of immunophenotypic algorithm for molecular subtype classification in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a report from the International DLBCL Rituximab-CHOP Consortium Program Study. Leukemia 2012;26:2103–2113.

Xu-Monette ZY, Moller MB, Tzankov A et al. MDM2 phenotypic and genotypic profiling, respective to TP53 genetic status, in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with rituximab-CHOP immunochemotherapy: a report from the International DLBCL Rituximab-CHOP Consortium Program. Blood 2013;122:2630–2640.

Camp RL, Dolled-Filhart M, Rimm DL . X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:7252–7259.

Ok CY, Chen J, Xu-Monette ZY et al. Clinical implications of phosphorylated STAT3 expression in de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:5113–5123.

Xu-Monette ZY, Wu L, Visco C et al. Mutational profile and prognostic significance of TP53 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with R-CHOP: report from an International DLBCL Rituximab-CHOP Consortium Program Study. Blood 2012;120:3986–3996.

Liu WM, Li R, Sun JZ et al. PQN and DQN: algorithms for expression microarrays. J Theor Biol 2006;243:273–278.

Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood 2004;103:275–282.

Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:1244.

Ok CY, Li L, Xu-Monette ZY et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of Epstein–Barr virus infection in de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in Western countries. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:2338–2349.

Hu S, Xu-Monette ZY, Balasubramanyam A et al. CD30 expression defines a novel subgroup of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with favorable prognosis and distinct gene expression signature: a report from the International DLBCL Rituximab-CHOP Consortium Program Study. Blood 2013;121:2715–2724.

de Paula H, Siqueira S, Pereira J et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, NOS: prognostic significance of immunohistochemical algorithms and biomarkers in newly diagnosed patients treated with rituximab plus CHOP-like regimens. Mod Pathol 2015;28:1365.

Rikiyama T, Curtis J, Oikawa M et al. GCF2: expression and molecular analysis of repression. Biochim Biophys Acta 2003;1629:15–25.

Ordentlich P, Downes M, Xie W, Genin A, Spinner NB, Evans RM . Unique forms of human and mouse nuclear receptor corepressor SMRT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999;96:2639–2644.

Obexer P, Geiger K, Ambros PF, Meister B, Ausserlechner MJ . FKHRL1-mediated expression of Noxa and Bim induces apoptosis via the mitochondria in neuroblastoma cells. Cell Death Differ 2007;14:534–547.

Jeffrey KL, Camps M, Rommel C, Mackay CR . Targeting dual-specificity phosphatases: manipulating MAP kinase signalling and immune responses. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2007;6:391–403.

Yamada H, Yanagisawa K, Tokumaru S et al. Detailed characterization of a homozygously deleted region corresponding to a candidate tumor suppressor locus at 21q11-21 in human lung cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2008;47:810–818.

Hofman K, Swinnen JV, Claessens F, Verhoeven G, Heyns W . The retinoblastoma protein-associated transcription repressor RBaK interacts with the androgen receptor and enhances its transcriptional activity. J Mol Endocrinol 2003;31:583–596.

Sanchez-Diaz A, Blanco MA, Jones N, Moreno S . HBP2: a new mammalian protein that complements the fission yeast MBF transcription complex. Curr Genet 2001;40:110–118.

Guo F, Sun A, Wang W et al. TRAF1 is involved in the classical NF-kappaB activation and CD30-induced alternative activity in Hodgkin's lymphoma cells. Mol Immunol 2009;46:2441–2448.

Wright CW, Rumble JM, Duckett CS . CD30 activates both the canonical and alternative NF-kappaB pathways in anaplastic large cell lymphoma cells. J Biol Chem 2007;282:10252–10262.

Wang X, Belguise K, Kersual N et al. Oestrogen signalling inhibits invasive phenotype by repressing RelB and its target BCL2. Nat Cell Biol 2007;9:470–478.

Iqbal J, Meyer PN, Smith LM et al. BCL2 predicts survival in germinal center B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with CHOP-like therapy and rituximab. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:7785–7795.

Jacque E, Billot K, Authier H, Bordereaux D, Baud V . RelB inhibits cell proliferation and tumor growth through p53 transcriptional activation. Oncogene 2013;32:2661–2669.

Schumm K, Rocha S, Caamano J, Perkins ND . Regulation of p53 tumour suppressor target gene expression by the p52 NF-kappaB subunit. EMBO J 2006;25:4820–4832.

Rocha S, Martin AM, Meek DW, Perkins ND . p53 represses cyclin D1 transcription through down regulation of Bcl-3 and inducing increased association of the p52 NF-kappaB subunit with histone deacetylase 1. Mol Cell Biol 2003;23:4713–4727.

Chen JY, Xu-Monette ZY, Deng L et al. Dysregulated CXCR4 expression promotes lymphoma cell survival and independently predicts disease progression in germinal center B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncotarget 2015;6:5597–5614.

Xu-Monette ZY, Tu M, Jabbar KJ et al. Clinical and biological significance of de novo CD5+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in Western countries. Oncotarget 2015;6:5615–5633.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health (R01CA138688 and 1RC1CA146299 to K.H.Y). KHY is also supported by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Research and Development Fund, an Institutional Research Grant Award, an MD Anderson Cancer Center Lymphoma Specialized Programs on Research Excellence (SPORE) Research Development Program Award, an MD Anderson Cancer Center Myeloma SPORE Research Development Program Award, a Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation Award, and MD Anderson Cancer Center Collaborative Funds with Roche Molecular System, Dai Sanyo Pharmaceutical, Adaptive Biotechnology, and HTG Molecular Diagnostics. CYO is the recipient of the advanced molecular pathology fellowship and hematopathology research awards; ZYXM is the recipient of the Harold C and Mary L Daily Endowment Fellowships and Shannon Timmins Fellowship for Leukemia Research Award. This work was also partially supported by National Cancer Institute and National Institutes of Health grants (P50CA136411 and P50CA142509) and by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ok, C., Xu-Monette, Z., Li, L. et al. Evaluation of NF-κB subunit expression and signaling pathway activation demonstrates that p52 expression confers better outcome in germinal center B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in association with CD30 and BCL2 functions. Mod Pathol 28, 1202–1213 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2015.76

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2015.76

This article is cited by

-

NF-κB p50 activation associated with immune dysregulation confers poorer survival for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients with wild-type p53

Modern Pathology (2017)

-

Diagnostic and predictive biomarkers for lymphoma diagnosis and treatment in the era of precision medicine

Modern Pathology (2016)

-

Primary testicular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma displays distinct clinical and biological features for treatment failure in rituximab era: a report from the International PTL Consortium

Leukemia (2016)

-

Prognostic and biological significance of survivin expression in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab-CHOP therapy

Modern Pathology (2015)

-

Clinical features, tumor biology, and prognosis associated with MYC rearrangement and Myc overexpression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with rituximab-CHOP

Modern Pathology (2015)