Abstract

Ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma has a relatively poor prognosis among the ovarian cancer subtypes because of its high chemoresistance. Differential diagnosis of clear cell adenocarcinoma from other ovarian surface epithelial tumors is important for its treatment. Napsin A is a known diagnostic marker for lung adenocarcinoma, and expression of napsin A is reported in a certain portion of thyroid and renal carcinomas. However, napsin A expression in ovarian surface epithelial tumors has not previously been examined. In this study, immunohistochemical analysis revealed that in 71 of 86 ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma patients (83%) and all of the 13 patients with ovarian clear cell adenofibroma, positive napsin A staining was evident. No expression was observed in 30 serous adenocarcinomas, 11 serous adenomas or borderline tumors, 19 endometrioid adenocarcinomas, 22 mucinous adenomas or borderline tumors, 10 mucinous adenocarcinomas, or 3 yolk sac tumors of the ovary. Furthermore, expression of napsin A was not observed in the normal surface epithelium of the ovary, epithelia of the fallopian tubes, squamous epithelium, endocervical epithelium, or the endometrium of the uterus. Therefore, we propose that napsin A is another sensitive and specific marker for distinguishing ovarian clear cell tumors (especially adenocarcinomas) from other ovarian tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Napsin A is an aspartic proteinase that is abundantly expressed in normal lung and kidney tissue and is also frequently expressed in lung adenocarcinomas.1, 2, 3, 4 Napsin A has a role in processing pulmonary surfactant B protein produced by alveolar type II pneumocytes;5, 6 thus, it has been reported to be a good diagnostic marker for the confirmation of primary lung adenocarcinoma together with thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1).7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Expression of napsin A is also observed in the fetal kidney14 and proximal tubules of the adult kidney, where it is most likely involved in protein catabolism.15 In neoplasms other than lung cancer, napsin A expression is most frequently observed in papillary renal carcinoma (79%), followed by other subtypes of renal cell carcinoma and thyroid carcinoma.16, 17 No expression was observed in breast, pancreatic, or colon carcinomas or mesotheliomas.16 It remains unclear whether napsin A exhibits some relationship with ovarian cancer.

Ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma is often associated with endometriosis,18, 19 and we have recently shown that stress caused by excess iron leads to amplification of the Met gene and carcinogenesis in the ovary.20, 21 Compared with serous adenocarcinoma, clear cell adenocarcinoma is resistant to standard platinum-based chemotherapy;22 thus, survival rates in patients with advanced stages of ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma are poor. Therefore, it is important to distinguish clear cell adenocarcinoma from other histological subtypes in ovarian cancer.

In this study, we analyzed a total of 195 cases of ovarian tumors and revealed that napsin A expression is frequently and specifically observed in clear cell tumors, clear cell adenocarcinomas, and adenofibromas.

Materials and methods

Patients and Tissue Samples

The local ethics committee (Internal Review Board) approved this study. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor samples from primary clear cell adenocarcinoma of the ovary were obtained from 73 patients who underwent surgical treatment from 1986 to 2009 at the Nagoya University Hospital and from 13 patients at the Nagoya City University Hospital during 2004–2013. Primary ovarian samples from 96 non-clear cell adenocarcinoma patients with ovarian tumors, 14 with atypical epithelium in endometriotic cysts, and 5 endometrial samples containing Arias–Stella reaction were obtained from 2004 to 2013 at the Nagoya City University Hospital, with the exception of 7 patients with serous adenocarcinoma and 6 patients with endometrioid adenocarcinoma, which were obtained from Nagoya University Hospital and Nagoya First Red Cross Hospital. All patients were treated with optimal debulking surgery. Histological diagnoses were reviewed and confirmed for all primary ovarian tumor samples by two experts in gynecological pathology (YY and TN).

Immunohistochemistry

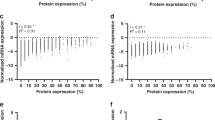

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded ovarian tumor blocks were sectioned into 3–5 μm slices for immunohistochemistry. Sections from whole blocks were subjected to immunohistochemical analyses to evaluate focal positivity. An anti-napsin A clone IP64 (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) primary antibody was used for immunohistochemical staining. Antibody binding was visualized using the auto-immunostaining apparatus Leica BOND MAX system (Leica Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, which included a heated incubation of the slides for 20 min in antigen retrieval buffer with an approximate pH of 9. Immunostaining of negative controls without primary antibody was also carried out in cases with excessive hemosiderosis. Napsin A staining was scored as weak (1+) or intense (2+), and we attempted to score the immunostaining negative/<10 (10), 10–20 (20), 20–30 (30), 30–40 (40), 40–50 (50), 50–60 (60), 60–70 (70), 70–80 (80), 80–90 (90), >90 (100)% for each case, and the larger percentage in each range was applied for calculating the positivity for each case. Finally, a case was interpreted as positive when cytoplasmic staining of more than 10% of the tumor cells was observed. Immunohistochemical results were confirmed by three pathologists (YY, TN, and SaT).

Results

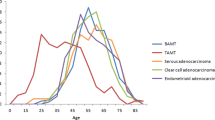

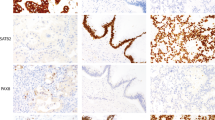

Napsin A expression was rather exclusively seen in the clear cell tumors including 86 ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma cases (11 of which were accompanied by a clear cell adenofibromatous component) and two independent clear cell adenofibroma cases. Of 86 ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma cases, 71 cases (83%) were napsin A-positive and 15 cases (17%) were napsin A-negative. A total of 58 of the 71 positive cases showed 2+ staining, and the remaining 13 cases were scored 1+. More than half of the positive cases showed 2+ immunostaining of more than 60% of the tumor cells (Table 1). Totally, the range of positivity for each case and the mean or median of the distribution were 20–100 (mean 61, median 70) %, and 30–90 (mean 62, median 70) % in the 1+ cases. All the remaining cases other than clear cell adenocarcinoma (30 serous adenocarcinoma, 19 endometrioid adenocarcinoma, 10 mucinous adenocarcinoma, 11 serous adenoma and borderline tumors, and 22 mucinous adenoma or borderline tumors, and 3 yolk sac tumors) were negative. The results of the histological features and immunostaining are summarized in Table 1. Figure 1 shows several representative images of the histology and napsin A immunostaining. Intense staining in the cytoplasm was observed in clear cell adenocarcinoma tumor cells (Figures 1a and b) but not in a typical serous adenocarcinoma (Figures 1c and d). Positive staining was also observed in the cytoplasm of clear cell adenofibroma (Figures 1e and f). However, five cases (three serous adenocarcinoma and two endometrioid adenocarcinoma) contained clear cell- or hob-nail-like change resembling clear cell adenocarcinoma (Figure 2a), and focal immunostaining of napsin A was observed in two of the five cases (Figure 2b). As the area of the positive staining did not exceed 10% of the tumor on the section, we considered these cases as napsin A-negative. Furthermore, we analyzed napsin A expression using 14 cases of endometriotic cysts containing atypical epithelium. Of the 14 cases, 11 were accompanied with ovarian adenocarcinoma, 3 of which were endometrioid and the other 8 clear cell adenocarcinomas. Interestingly, atypical epithelium of five cases, all of which contained clear cell adenocarcinoma component, was positive at least focally by napsin A immunostaining (Table 1 and Figures 2c and d). All of the five endometrial samples with Arias–Stella reaction were also positive for napsin A, although the percentage of positive glands in each case varied (Table 1 and Figures 2e and f). Other normal tissue samples (three endometrial, two endocervical epithelia, one squamous epithelium of the uterine cervix, one ovarian surface epithelium, and one epithelium of adenomyosis) were all negative for napsin A.

Representative histology and napsin A immunostaining results for ovarian clear cell tumors and serous adenocarcinoma. ((a, c, e) H & E staining, (b, d, f) napsin A immunostaining). (a, b) A clear cell adenocarcinoma case with clear cells and hobnail cells (a) showing intense cytoplasmic staining for napsin A (b). (c, d) A serous adenocarcinoma with psammoma bodies (c) totally negative for Napsin A (d). (e, f) A clear cell adenofibroma with cysts (e) showing positivity for napsin A in the epithelial lining cells (f). Scale bar: 100 μm.

Napsin A immunostaining results for cases mimicking ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. ((a, c, e) H & E staining, (b, d, f) napsin A immunostaining). (a, b) An endometrioid adenocarcinoma case containing clear cells or hob-nail-like cells mimicking clear cell adenocarcinoma (a) showing focal cytoplasmic staining for napsin A (b). (c, d) Atypical epithelium in a case with endometriosis (c) showing focal positivity for napsin A (d). (e, f) Endometrial sample with Arias–Stella reaction mimicking clear cell adenocarcinoma (e) showing intense cytoplasmic positivity for napsin A (f). Scale bar: 100 μm.

Discussion

Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the ovary has recently been regarded as a unique subtype of ovarian cancer with specific cytokine production and frequent amplification of the Met gene, which is associated with endometriosis (reviewed by Penson et al23). Furthermore, ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma generally is chemoresistant,24 likely because of its relatively slow growth rate. These characteristics highlight the importance of distinguishing clear cell adenocarcinoma from other ovarian carcinomas. Clear cell adenocarcinoma may exhibit papillary histology similar to that of serous adenocarcinomas,25, 26 and serous borderline tumors may have hob-nail-like cells mimicking clear cell adenocarcinoma pathology.27 Endometrioid neoplasms may also contain clear cells;28 thus, a differential diagnosis between clear cell adenocarcinoma and other histological subtypes is necessary. Some yolk sac tumors also show similar histology to clear cell adenocarcinoma.29 As a fraction of ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma may produce alpha-fetoprotein,30, 31 diagnostic markers distinguishing between these two tumors are also required.

Recently, several molecules have been proposed as specific markers for clear cell adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Among them, hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 beta (HNF1β) seems to be the best because of its high sensitivity and specificity.32, 33 However, one study reported HNF1β positivity in the nuclei of normal and tumor cells in the endometrium,34 and the establishment of other markers may also be useful for differential diagnosis of clear cell adenocarcinoma. Annexin-A4,35, 36 HOXA10,37 phospho-serine aminotransferase,36 and glypican 338 are all suitable candidates. A recent study has shown that a certain proportion of papillary serous adenocarcinoma also exhibits Annexin-A4 expression related to chemoresistance,39 and the expression of HOXA10 or glypican 3 is less frequently associated with poor outcome.37, 38, 40 Glypican 3 is also known to be expressed in yolk sac tumors of the ovary.38 In this study, all of the 93 primary ovarian surface epithelial tumors that were not of the clear cell subtype and three cases of yolk sac tumors were all negative for napsin A staining, with the exception of focal (<10% area) staining of serous and endometrioid adenocarcinoma cases with clear cell- or hob-nail changes resembling clear cell adenocarcinoma. Thus, we consider napsin A to be another suitable marker to specifically distinguish clear cell adenocarcinoma from other ovarian tumors with a relatively high sensitivity. Furthermore, because napsin A is an established marker for lung adenocarcinomas,7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 we assume that napsin A immunostaining will be easily applied to routine surgical pathology specimens in laboratories. In this study, we determined the criteria for positive napsin A immunostaining as >10% tumor area for differential diagnosis between histological subtypes of ovarian adenocarcinomas, and given that focal positivity is observed in those other than clear cell adenocarcinoma, careful interpretation is required when applying this method on small biopsy specimen.

In this study, napsin A was expressed in all of the 13 clear cell adenofibroma samples. However, no expression was observed in the normal endometrium and adenomyosis samples. All of the six endometriosis cases not accompanied with clear cell adenocarcinoma including those with endometrioid adenocarcinomas were also negative. However, five of the eight cases with both endometriosis and clear cell adenocarcinoma, the atypical and normal-looking epithelium at the surface of the endometriotic cysts showed at least focal napsin A positivity. As positive expression of HNF1β is reported in the nuclei of the epithelial cells in the majority of the cases with endometriosis,33 it is possible that napsin A may have a different role than HNF1 β in ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma tumor cells. However, further analysis using more cases is necessary for clarification. Most recently, similar studies also have demonstrated frequent napsin A expression in clear cell adenocarcinomas of the ovary and endometrium.41, 42 In this study, endometrial epithelial cells undergoing Arias–Stella reaction were also frequently positive for napsin A, and more studies are required for the evaluation of the biological meanings of these findings. Loss of napsin A expression is associated with a poor prognosis in lung cancer patients,43 and some of our cases had also lost napsin A expression in tumor cells with high-grade morphology or Met amplification (data not shown). In this study, napsin A was not expressed in any of the tumor cells of any ovarian tumors other than those of the clear cell subtype; thus, napsin A staining was regarded as positive even when only a small amount of positive cells were present in the tissue section. Further analyses are necessary to clarify the biological meaning of napsin A expression, particularly with regard to the association of napsin A with the biological behavior of tumor cells, which may influence the prognosis of the patients.

Recent studies have shown that napsin A is expressed in various tumors other than lung adenocarcinomas, including pulmonary sclerosing hemangioma, renal and thyroid carcinomas, and adrenal cortical neoplasms.16, 17, 44, 45, 46 Renal papillary carcinomas are known to exhibit Met amplification, and renal clear cell carcinomas are known to exhibit vHL mutations leading to overexpression.47 Thus, we consider that clear cell adenocarcinomas of the ovary and kidney have many common characteristics, including clear cell or papillary morphology, and gene mutation and expression.48 Lung metastases of renal cancers are difficult to distinguish from primary lung adenocarcinomas by napsin A immunostaining,49 and our data highlight this difficulty by revealing possible napsin A expression in lung metastases of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the ovary.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that napsin A is expressed in the majority of ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma and all of the clear cell adenofibromas. We suggest that napsin A should be included in the immunohistochemical panel for the differential diagnosis of ovarian surface epithelial tumors.

References

Tatnell PJ, Powell DJ, Hill J et al. Napsins: new human aspartic proteinases. Distinction between two closely related genes. FEBS Lett 1998;441:43–48.

Chuman Y, Bergman A, Ueno T et al. Napsin A, a member of the aspartic protease family, is abundantly expressed in normal lung and kidney tissue and is expressed in lung adenocarcinomas. FEBS Lett 1999;462:129–134.

Schauer-Vukasinovic V, Bur D, Kling D et al. Human napsin A: expression, immunochemical detection, and tissue localization. FEBS Lett 1999;462:135–139.

Hirano T, Auer G, Maeda M et al. Human tissue distribution of TA02, which is homologous with a new type of aspartic proteinase, napsin A. Jpn J Cancer Res 2000;91:1015–1021.

Brasch F, Ochs M, Kahne T et al. Involvement of napsin A in the C- and N-terminal processing of surfactant protein B in type-II pneumocytes of the human lung. J Biol Chem 2003;278:49006–49014.

Ueno T, Linder S, Na CL et al. Processing of pulmonary surfactant protein B by napsin and cathepsin H. J Biol Chem 2004;279:16178–16184.

Ueno T, Linder S, Elmberger G . Aspartic proteinase napsin is a useful marker for diagnosis of primary lung adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 2003;88:1229–1233.

Hirano T, Gong Y, Yoshida K et al. Usefulness of TA02 (napsin A) to distinguish primary lung adenocarcinoma from metastatic lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer 2003;41:155–162.

Terry J, Leung S, Laskin J et al. Optimal immunohistochemical markers for distinguishing lung adenocarcinomas from squamous cell carcinomas in small tumor samples. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:1805–1811.

Ye J, Findeis-Hosey JJ, Yang Q et al. Combination of napsin A and TTF-1 immunohistochemistry helps in differentiating primary lung adenocarcinoma from metastatic carcinoma in the lung. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2011;19:313–317.

Zhang P, Han YP, Huang L et al. Value of napsin A and thyroid transcription factor-1 in the identification of primary lung adenocarcinoma. Oncol Lett 2010;1:899–903.

Whithaus K, Fukuoka J, Prihoda TJ et al. Evaluation of napsin A, cytokeratin 5/6, p63, and thyroid transcription factor 1 in adenocarcinoma versus squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012;136:155–162.

Warth A, Muley T, Herpel E et al. Large-scale comparative analyses of immunomarkers for diagnostic subtyping of non-small-cell lung cancer biopsies. Histopathology 2012;61:1017–1025.

Mori K, Kon Y, Konno A et al. Cellular distribution of napsin (kidney-derived aspartic protease-like protein, KAP) mRNA in the kidney, lung and lymphatic organs of adult and developing mice. Arch Histol Cytol 2001;64:319–327.

Mori K, Shimizu H, Konno A et al. Immunohistochemical localization of napsin and its potential role in protein catabolism in renal proximal tubules. Arch Histol Cytol 2002;65:359–368.

Bishop JA, Sharma R, Illei PB et al. and thyroid transcription factor-1 expression in carcinomas of the lung, breast, pancreas, colon, kidney, thyroid, and malignant mesothelioma. Hum Pathol 2010;41:20–25.

Chernock RD, El-Mofty SK, Becker N et al. Napsin a expression in anaplastic, poorly differentiated, and micropapillary pattern thyroid carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:1215–1222.

Kennedy AW, Biscotti CV, Hart WR et al. Ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1989;32:342–349.

Pearce CL, Templeman C, Rossing MA et al. Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:385–394.

Yamaguchi K, Mandai M, Toyokuni S et al. Contents of endometriotic cysts, especially the high concentration of free iron, are a possible cause of carcinogenesis in the cysts through the iron-induced persistent oxidative stress. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:32–40.

Yamashita Y, Akatsuka S, Shinjo K et al. Met is the most frequently amplified gene in endometriosis-associated ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma and correlates with worsened prognosis. PloS One 2013;8:e57724.

Sugiyama T, Kamura T, Kigawa J et al. Clinical characteristics of clear cell carcinoma of the ovary - a distinct histologic type with poor prognosis and resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy. Cancer 2000;88:2584–2589.

Penson RT, Dizon DS, Birrer MJ . Clear cell cancer of the ovary. Curr Opin Oncol 2013;25:553–557.

Itamochi H, Kigawa J, Sugiyama T et al. Low proliferation activity may be associated with chemoresistance in clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Obst Gynecol 2002;100:281–287.

Sangoi AR, Soslow RA, Teng NN et al. Ovarian clear cell carcinoma with papillary features: a potential mimic of serous tumor of low malignant potential. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:269–274.

DeLair D, Oliva E, Kobel M et al. Morphologic spectrum of immunohistochemically characterized clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a study of 155 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:36–44.

Ohishi Y, Oda Y, Kurihara S et al. Hobnail-like cells in serous borderline tumor do not represent concomitant incipient clear cell neoplasms. Hum Pathol 2009;40:1168–1175.

Silva EG, Young R . Endometrioid neoplasms with clear cells: a report of 21 cases in which the alteration is not of typical secretory type. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:1203–1208.

Ballotta MR, Bianchini E, Borghi L et al. Clear cell carcinoma simulating the ‘endometrioid-like variant’ of yolk sac tumor. Pathologica 1995;87:87–90.

Cetin A, Bahat Z, Cilesiz P et al. Ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma producing alpha-fetoprotein: case report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2007;28:241–244.

Takahashi YMH, Hamada S, Urasaki K et al. Alpha-fetoprotein producing ovarian clear cell carcinoma with a neometaplasia to hepatoid carcinoma arising from endometriosis: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2011;37:1842–1846.

Tsuchiya A, Sakamoto M, Yasuda J et al. Expression profiling in ovarian clear cell carcinoma: identification of hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 beta as a molecular marker and a possible molecular target for therapy of ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Am J Pathol 2003;163:2503–2512.

Kato N, Sasou S, Motoyama T . Expression of hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta (HNF-1beta) in clear cell tumors and endometriosis of the ovary. Mod Pathol 2006;19:83–89.

Fadare O, Liang SX . Diagnostic utility of hepatocyte nuclear factor 1-beta immunoreactivity in endometrial carcinomas: lack of specificity for endometrial clear cell carcinoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2012;20:580–587.

Miao Y, Cai B, Liu L et al. Annexin IV is differentially expressed in clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2009;19:1545–1549.

Toyama A, Suzuki A, Shimada T et al. Proteomic characterization of ovarian cancers identifying annexin-A4, phosphoserine aminotransferase, cellular retinoic acid-binding protein 2, and serpin B5 as histology-specific biomarkers. Cancer Sci 2012;103:747–755.

Li B, Jin H, Yu Y et al. HOXA10 is overexpressed in human ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma and correlates with poor survival. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2009;19:1347–1352.

Maeda D, Ota S, Takazawa Y et al. Glypican-3 expression in clear cell adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Mod Pathol 2009;22:824–832.

Choi CH, Sung CO, Kim HJ et al. Overexpression of annexin A4 is associated with chemoresistance in papillary serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Hum Pathol 2013;44:1017–1023.

Umezu T, Shibata K, Kajiyama H et al. Glypican-3 expression predicts poor clinical outcome of patients with early-stage clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. J Clin Pathol 2010;63:962–966.

Kandalaft PIL, Gown AM . The lung-restricted marker napsin A is highly expressed in clear cell carcinomas of the ovary. Mod Pathol 2012;25:279A.

Fadare O, Desouki MM, Gwin K et al. Frequent expression of napsin a in clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium: potential diagnostic utility. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38:189–196.

Lee JG, Kim S, Shim HS . Napsin A is an independent prognostic factor in surgically resected adenocarcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer 2012;77:156–161.

Rossi G, Cadioli A, Mengoli MC et al. Napsin A expression in pulmonary sclerosing haemangioma. Histopathology 2012;60:361–363.

Schmidt LA, Myers JL, McHugh JB . Napsin A is differentially expressed in sclerosing hemangiomas of the lung. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012;136:1580–1584.

Ballard M, Sangoi A, McKenney JK et al. Napsin A staining in adrenal cortical neoplasms. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2013;137:883.

Lin F, Shi J, Liu H et al. Immunohistochemical detection of the von Hippel-Lindau gene product (pVHL) in human tissues and tumors: a useful marker for metastatic renal cell carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma of the ovary and uterus. Am J Clin Pathol 2008;129:592–605.

Nolan LP, Heatley MK . The value of immunocytochemistry in distinguishing between clear cell carcinoma of the kidney and ovary. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2001;20:155–159.

Kadivar M, Boozari B . Applications and limitations of immunohistochemical expression of ‘Napsin-A’ in distinguishing lung adenocarcinoma from adenocarcinomas of other organs. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2013;21:191–195.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms J Takekawa, Mr K Kato, and Mr N Misawa and the members of the Department of Pathology, Nagoya City University Hospital, for their excellent technical assistance, and Dr K Shinjo, Dr S Takeshita, and Dr K Kobayashi from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Nagoya University Hospital or Nagoya City University Hospital for providing patient samples and clinical information. This study was partly supported by a Grant-in-Aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Tokyo, Japan, for Scientific Research (no. 23590394 to YY).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yamashita, Y., Nagasaka, T., Naiki-Ito, A. et al. Napsin A is a specific marker for ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol 28, 111–117 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.61

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.61

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comparative analysis of response to treatments and molecular features of tumor-derived organoids versus cell lines and PDX derived from the same ovarian clear cell carcinoma

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2023)

-

Synchronous bilateral primary ovarian cancer with right endometroid carcinoma and left high-grade serous carcinoma: a case report and literature review

BMC Women's Health (2022)

-

Napsin A Expression in Subtypes of Thyroid Tumors: Comparison with Lung Adenocarcinomas

Endocrine Pathology (2020)

-

Malignant ascites occurs most often in patients with high-grade serous papillary ovarian cancer at initial diagnosis: a retrospective analysis of 191 women treated at Bayreuth Hospital, 2006–2015

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2019)