Abstract

Opportunities to study the natural history of ductal carcinoma in situ are rare. A few studies of incompletely excised lesions in the premammographic era, retrospectively recognized as ductal carcinoma in situ, have demonstrated a proclivity for local recurrence in the original site. The authors report a follow-up study of 45 women with low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ treated by biopsy only, recognized retrospectively during a larger review of surgical pathology diagnoses and original histological slides for 26 539 consecutive breast biopsies performed at Vanderbilt, Baptist and St Thomas Hospitals in Nashville, TN from 1950 to 1989. Long-term follow-up was previously reported on 28 of these women. Sixteen women (36%) developed invasive breast carcinoma, all in the same breast and quadrant as their incident ductal carcinoma in situ. Eleven invasive breast carcinomas were diagnosed within 10 years of the ductal carcinoma in situ biopsy. Subsequent cases were diagnosed at 12, 23, 25, 29 and 42 years. Seven women, including one who developed invasive breast cancer 29 years after her ductal carcinoma in situ biopsy, developed distant metastasis, resulting in death 1–7 years postdiagnosis of invasive breast carcinoma. The natural history of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ may extend more than four decades, with invasive breast cancer developing at the same site as the index lesion. This protracted natural history differs markedly from that of patients with high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ or any completely delimited ductal carcinoma in situ excised to negative margins. This study reaffirms the importance of complete margin evaluation in women treated with breast conservation for ductal carcinoma in situ as well as balancing recurrence risk with possible treatment-related morbidity for older women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

For more than 20 years, an overwhelming body of evidence has demonstrated ductal carcinoma in situ diagnosed by current criteria to be a surgical disease, mandating excision to negative margins. Thus opportunities to study the natural history of ductal carcinoma in situ are very rare. Before 1980, lesions diagnosed as ductal carcinoma in situ typically reached clinical attention by the presence of a palpable breast mass or nipple discharge, were usually high grade and may have even been associated with foci of invasive carcinoma. In this article, we report the follow-up on 45 women with small, low-grade, ductal carcinoma in situ retrospectively diagnosed utilizing current criteria,1, 2, 3 who were treated by biopsy only at the time of their original evaluation. Twenty-eight of these women were reported previously.2, 4, 5, 6 These patients were recognized during a larger review of surgical pathology diagnoses and original tissue slides for 26 539 consecutive biopsies performed at Vanderbilt, Baptist and St Thomas Hospitals in Nashville, TN, from 1950 through 1989.2, 4, 5, 6 In the 1950s and during most of the 1960s, when many of these biopsies were originally examined, small, lower-grade ductal carcinoma in situ was not diagnosed; therefore, these women were treated by biopsy only after a benign interpretation.

Materials and methods

Retrospective Cohort Study

These women were recognized retrospectively during a larger review of surgical pathology diagnoses and original histological slides for 26 539 consecutive breast biopsies performed at Vanderbilt, Baptist and St Thomas Hospitals from 1950 through 1989, as described previously.2 In brief, the initial histological review of all available slides from the first 11 760 women was carried out by one of the authors (DLP), who reviewed all biopsies with diagnoses other than malignancy or abscess for the presence of epithelial proliferative disease, atypical hyperplasia and carcinoma in situ. All diagnoses of atypical hyperplasia and carcinoma in situ were reviewed by Dr Lowell W Rogers5 (deceased), and any discrepancies were resolved over the double-headed microscope. The subsequent 14 779 biopsies were reviewed by Page and colleagues,4, 5, 6 with the all cases reviewed by at least two pathologists and all diagnoses of atypical hyperplasia and carcinoma in situ independently reviewed by a third pathologist (usually DLP unless he was the primary reviewer of the case). Any discrepancies were resolved with a multi-headed microscope by three breast pathologists (MES, JFS, DLP). For the purpose of this study, original slides and reports from all 45 women retrospectively diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ and all available slides and reports from subsequent carcinomas were re-reviewed by one of the current authors (MES). Approximately 50% of the index biopsies were entirely submitted, whereas the remainder were representatively sampled. According to the pathology reports, the representative sampling included all fibrous tissue and grossly evident masses. As more than two-thirds of the women in this study were biopsied before the advent of mammographic screening, we have not discussed the very limited mammographic data available. Information on hormonal status at the time of the index biopsy with ductal carcinoma in situ and family history of breast cancer were self-reported by patients at the time of follow-up. A protocol to obtain informed consent and follow-up information was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board (VU IRB no. 2548). Informed consent to participate in the Nashville Breast Cohort2 was obtained from all patients and the institutional review boards of the participating hospitals in the approved study protocol. Patients eligible for follow-up were residents of Tennessee or Kentucky at the time of entry biopsy and without a previous diagnosis of breast cancer. Follow-up was obtained by contacting patients or relatives if the patients were deceased. Follow-up was continued until the time of death or last available information from the patient or next of kin.

Histological Definitions

In the current study, ductal carcinoma in situ is defined as a monotonous, cohesive cell proliferation fulfilling at least the following criteria: (1) complete involvement of at least two adjacent spaces, (2) at least one of the spaces is a true duct, and (3) the lesion measures at least 2.0 mm in the greatest dimension.1, 2, 3 The histological patterns, including cribriform, micropapillary, solid or a mixture, were recorded. All examples of ductal carcinoma in situ were graded.7 Atypical ductal hyperplasia is defined as a lesion with a pure cell population but limited in size and incompletely occupying the involved space(s). This definition has been extensively validated epidemiologically.8, 9, 10, 11 Atypical ductal hyperplasia usually affects only lobular units. Invasive lobular carcinoma, classic type, was diagnosed if the tumor showed a >90% single cell infiltrative pattern and was of low cytological grade throughout.12, 13 Invasive mammary carcinoma, no special type, was diagnosed when tumors lacked features diagnostic of special types such as pure tubular or classic invasive lobular carcinomas.12, 13 No special type carcinomas with special type features were diagnosed when features of special type carcinomas were present in 10–90% of the invasive carcinoma.14

Statistical Methods

The cumulative incidence of invasive breast cancer and breast cancer mortality are estimated with the Kaplan–Meier morbidity and mortality curves. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals for these estimates were derived using the Greenwood’s formula.15

Results

In this article, we report a follow-up study of 45 women with low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ who were treated by biopsy only. Extended follow-up data are provided on an original cohort of 28 women plus 17 more recently identified patients. All women who reported having undergone menopause had done so starting at ≥50 years. Twenty-one women (46%) were premenopausal at the time their biopsy containing the index ductal carcinoma in situ (Table 1). The remaining 53% were postmenopausal. This difference was not statistically significant. Among women who developed subsequent invasive cancer, there were equal numbers of premenopauseal (n=8) and postmenopausal (n=8) women. In comparison, 41% (12/29) of the women who did not subsequently develop invasive carcinoma were premenopausal. Although suggesting a trend toward a greater number of premenopausal women developing subsequent invasive carcinoma, this relationship did not reach statistical significance. Six women had a family history of breast cancer, two of whom were among the women developing subsequent invasive carcinoma.

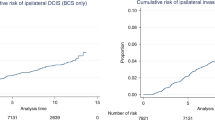

The morbidity graph (Figure 1, left panel) shows the cumulative incidence of invasive breast carcinoma among the 45 women, illustrating that any woman with low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ who has not received definitive treatment remains at risk for a prolonged period after this diagnosis. The risk of invasive carcinoma was greatest in the first 15 years and declined slightly as follow-up was extended. Sixteen of the 45 women (36%) developed invasive breast carcinoma, all in the same quadrant and in the same breast from which the original biopsy with ductal carcinoma in situ was excised (Table 1). These carcinomas were diagnosed over a total of 47 years of follow-up. Among patients who developed invasive breast carcinoma, the average time to invasive breast carcinoma diagnosis was 13 years (range 3–42 years). The median follow-up was 26 years (range 1–47 years) for women who did not develop carcinoma (Table 2). Eleven women were diagnosed with IBCs within 10 years of the ductal carcinoma in situ biopsy. Subsequent cases were diagnosed at 12, 23, 25, 29 and 42 years after their original ductal carcinoma in situ biopsy. The risk of subsequent invasive breast cancer was not significantly affected by the patient’s menopausal status at the time of their index biopsy.

The year of last follow-up was 2009. The first of the five women who had invasive carcinomas identified since the previously published follow-up in 20056 was diagnosed 3 years after her original ductal carcinoma in situ biopsy. She was treated by mastectomy for an intermediate grade, no special type carcinoma with negative lymph nodes. The patient died 15 years later of other causes (Table 1). The second patient developed invasive breast carcinoma 5 years after her original ductal carcinoma in situ biopsy. Her mastectomy specimen contained a pure invasive lobular carcinoma with positive lymph nodes. The patient died 2 years later of metastatic breast cancer. The third woman developed invasive breast carcinoma 8 years after her initial biopsy and underwent mastectomy for an intermediate grade, no special type carcinoma with lobular features with positive axillary lymph nodes. The patient died 2 years later of metastatic breast cancer. The fourth patient developed invasive breast carcinoma of unknown type and grade with positive lymph nodes 12 years after her original ductal carcinoma in situ biopsy. She died of other causes 15 years later without evidence of local or distant recurrence. The last woman was diagnosed with invasive breast carcinoma of unknown type, grade and lymph node status 25 years after her ductal carcinoma in situ diagnosis. She died of other causes <1 year following diagnosis.

Original slides for histological typing of ductal carcinoma in situ were available for all 45 women. Cribriform was the most common pattern and was present in 15 cases (Table 3). Other patterns observed in descending order were solid (11 cases), mixed cribriform-solid-micropapillary (10), pure micropapillary (5 cases), pure apocrine (2 cases) and encysted non-invasive papillary carcinoma. There was no relationship between the histological pattern of the ductal carcinoma in situ and the subsequent development of invasive carcinoma.

Three additional women developed a second ductal carcinoma in situ (Table 1). One was diagnosed with recurrent ductal carcinoma in situ in the same quadrant of the same breast 3 years after her index ductal carcinoma in situ. Her index ductal carcinoma in situ was an encysted non-invasive papillary carcinoma with apocrine cytology. Her recurrence was also low-grade with pure apocrine cytology. She underwent a unilateral mastectomy and died of heart failure 5 years after her second diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ without evidence of recurrent carcinoma. The second woman was diagnosed with a subsequent intermediate grade ductal carcinoma in situ of unknown type in the same breast 23 years after her index ductal carcinoma in situ. She was treated by bilateral mastectomy. At the time of last follow-up 17 years later, she was alive and well. The third woman developed a second ductal carcinoma in situ in the same quadrant of the same breast 27 years after her initial biopsy with ductal carcinoma in situ. At the time of last follow-up, she was alive and well 1 year after undergoing a unilateral mastectomy without evidence of disease.

At the time of last follow-up, 30 of the 45 women were deceased. Seven died of metastatic breast cancer, and 23 died of causes unrelated to their breast cancer diagnoses (Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 1, right panel). With respect to the 16 women with subsequent invasive breast carcinoma, 13 were deceased at the time of last follow-up. The women with metastatic breast cancer died at an average of 3 years after their invasive breast carcinoma diagnosis (range, 1–7 years). Six died within 5 years of diagnosis, and 1 died within 7 years of diagnosis. Of the remaining 9 women, all died from other causes at an average of 13 years (range 2–19 years) after diagnosis and at an average of 24 years (range 12–39 years) after the original biopsy with DCIS.

Discussion

This cohort of women with low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ was retrospectively identified from a larger, completely characterized cohort of women with benign breast disease. When these lesions were originally examined, low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ was not diagnosed, thus these women were treated by biopsy only. Sixteen of the 45 women (36%) developed invasive breast carcinoma, all in the same quadrant and in the same breast from which the original biopsy with ductal carcinoma in situ was taken. These carcinomas were diagnosed over a total of 47 years of follow-up. The methodology and findings of our study are similar to those of Betsil et al,16 who examined all available histological slides from 8609 benign biopsies performed from 1940 through 1950 at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Those authors identified 25 women with previously undiagnosed low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ who were treated by biopsy only. Among 10 women with long-term follow-up, which averaged 22 years, 7 women developed invasive breast carcinoma at an average of 10 years after their initial biopsy (range, 7–30 years), all in the same breast as the ductal carcinoma in situ. Using the same group of patients, Rosen et al17 subsequently conducted a retrospective review of >8000 biopsies originally reported as benign and identified a total of 30 patients with micropapillary ductal carcinoma in situ. Long-term follow-up was available on 15 of these women. Eight women (53%) developed invasive cancer in the same breast as the index ductal carcinoma in situ, with an average follow up of 9 years.

More recently, a case–control study of 1877 biopsies in the Nurses’ Health Study, originally diagnosed as benign,18 identified 13 biopsies containing ductal carcinoma in situ, which were not recognized on initial review. Six of these women developed subsequent invasive breast cancer. Among the 13 ductal carcinoma in situ, 4 were low-grade, 6 intermediate-grade and 3 were high-grade lesions. Invasive breast cancer developed in two patients with low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ, two patients with intermediate-grade ductal carcinoma in situ and two patients with high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ.

These three studies likely represent the only information that ever will be available on the natural history of ductal carcinoma in situ. These results are highly relevant to current circumstances, because detection of lesser examples of ductal carcinoma in situ has increased dramatically with the practice of high-quality routine mammographic screening,19, 20 with ductal carcinoma in situ now representing approximately 20% of screen-detected breast cancers. Evidence now overwhelmingly demonstrates that ductal carcinoma in situ is a spectrum of disease ranging from extensive, high-grade lesions, most likely requiring mastectomy for eradication, to small, low-grade lesions, which can be cured effectively by excision alone.21 The existing natural history studies summarized above4, 5, 6, 16, 17, 18 and reported herein indicate that high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ left untreated will evolve to an invasive carcinoma in <5 years in >50% of patients. Although untreated, low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ has a similar capacity to evolve into invasive carcinoma in 35–50% of patients, the time course is significantly protracted and may span >40 years. Given these critical differences, it is reasonable to expect that a few women with inadequately treated, lower-grade lesions also would exhibit local recurrence and distant spread as their follow-up interval is extended.22, 23 However, because of the important therapeutic implications, it will be important to document the degree to which these events actually represent a threat to life or even occur within the lifetime of the woman.

Although the morbidity graph (Figure 1, left panel) illustrates that any woman with low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ who has not received definitive treatment remains at risk for a prolonged period after this diagnosis, it also suggests that these women may have stable ductal carcinoma in situ for decades. The increased detection of small, low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ with widespread use of mammographic screening programs mandates constant re-evaluation of who we should be treating, how much and when? There is now good evidence that planned local excision with complete histological examination and assurance of negative margins results in efficient and effective cure in most instances.21, 24, 25, 26 This fact emphasizes the need for consideration of less aggressive therapy (local excision only) when these lesions are limited in size, and the recurrence interval well may be beyond a reasonable life expectancy for the patient.

Thus approach to treatment must be based on a combination of the natural history and the extent of mammary involvement. Precise case definitions are of critical importance to these considerations. The findings of Betsil et al and of the current series,4, 5, 6, 16 supplemented by later studies in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ who underwent planned excision,21, 24, 25, 27 provide a rational basis for prognostication and therapeutic recommendations for ductal carcinoma in situ. Fundamental to these studies was the careful definition of each lesion, primarily by size, grade and histological features. We now know that margin status is the critical delimiting element and the most important determinant of local recurrence.26 In fact, pathological review of a subset of the patients that comprised the two largest cooperative trials for treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ, the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-17 and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), demonstrated that most local failures were in women with high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ and with positive or unknown margin status22, 23 and that treatment with radiation therapy appeared to reduce but did not eliminate the risk.22, 23 In addition, patients with high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ have a high risk of developing life-threatening distant metastasis after invasive local recurrence.22, 28 Most importantly, radiation therapy had no effect on the most important outcome measure, deaths due to breast cancer in both studies.22, 23 The long-term follow-up of both studies continue to report no survival advantage from adjuvant radiotherapy.28, 29, 30 A report of four randomized clinical trials of radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group in the UK similarly found no significant effect on breast cancer mortality associated with use of radiation therapy.31 Most recently, Lee et al32 found no statistically significant difference in local recurrence rates between women receiving or not receiving adjuvant radiation therapy in combination with breast conservation for ductal carcinoma in situ at St Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center, NY between 1990 and 2009. In fact, in the NSABP-17 and B-24 trials, the radiated group suffered a slight increase in mortality after 15 years of follow-up compared with the patients who received no radiation therapy.29, 30 Furthermore, additional long-term follow-up on the women in the Silverstein study26, 33 has now shown a greater risk of recurrences in the radiation arm of that cohort and that these recurrences are more commonly invasive.33 Of further concern is the fact that the median time to local recurrence for irradiated patients was more than twice as long when compared with non-irradiated patients. This strongly suggests that radiation therapy delayed rather than prevented local recurrence. These results re-emphasize the criticality of complete margin evaluation and argue strongly against the use of radiation therapy for women with low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ treated by breast conservation.

Epidemiologically speaking, small, low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ is the pivotal lesion in understanding the borderline between malignancy and non-malignancy in the female breast. Low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ is a non-obligate precursor and, if left without further treatment, predicts for regional risk and will eventuate in invasive carcinoma in the same site in the same breast in 30% of patients within 15 years. Over time, any residual DCIS either regresses, remains dormant after biopsy alone, expands extensively as in situ disease or progresses to invasive carcinoma with metastatic and death-dealing capacity. These invasive carcinomas, with few exceptions, arise in the same quadrant of the same breast as the original biopsy. The current series and the series reported by Betsil et al16 provide important biological validation of the diagnostic criteria currently used to delimit small, low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ lesions.1, 2, 3 They indicate a striking dividing point biologically between low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ lesions and the cytologically similar but lesser lesions of atypical ductal hyperplasia.2, 34 Atypical ductal hyperplasia indicates a small, generalized, increased risk of breast carcinoma in both breasts that is approximately one half that of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ lesions, and these cancers may occur at any site rather than in the locality of the incident ductal carcinoma in situ.8, 9, 10, 11

However, practically speaking, an excisional biopsy of the mammographic abnormality is an appropriate initial therapy for patients with either diagnosis and may be curative. Therefore, low-grade lesions in core needle biopsies, by nature a sampling, should be conservatively diagnosed. After a diagnosis of DCIS of very limited size on core biopsy, we well recognize the phenomenon of women opting for bilateral mastectomy with the subsequent finding of no residual lesion in the index breast or receiving adjuvant radiation therapy despite a negative excisional biopsy. Knowing this, it is our current practice as well as others35 to diagnose such borderline lesions as well-developed atypical ductal hyperplasia, with a comment that the lesion will be best characterized at the time of formal excision. A recent study by VandenBussche et al35 provides sound evidence to justify this approach. They found among 74 patients diagnosed with well-developed ‘marked’ atypical ductal hyperplasia at their institution on core needle biopsy followed by excisional biopsy, 27% had benign findings or atypical lobular hyperplasia, 24% had additional atypical ductal hyperplasia, 45% had ductal carcinoma in situ and 4% had invasive carcinoma associated with ductal carcinoma in situ. The patients without subsequent ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive cancer did not undergo further surgery, postoperative radiation or experience local recurrence of carcinoma during the 54-month average follow-up period. Among patients with ductal carcinoma and invasive cancer upon excision, <20% required mastectomy. These findings suggest no woman was harmed from this conservative approach, and they benefitted from avoidance of complications related to more extensive surgery, axillary node biopsy or dissection and radiation therapy.

Age may also have a role in therapeutic decision making. Kong et al36 report long-term follow-up on women in the Ontario Cohort Study with ductal carcinoma in situ treated by breast conservation and radiation therapy. When recurrence risk was stratified by age, the 10-year cumulative local recurrence rate for women aged <45 years was a striking 27%, while it was 14% for women aged 45–50 years and 11% for women aged >50 years (P<0.0001). In multivariate analyses, positive or unreported margin status and additionally high nuclear grade in the index ductal carcinoma in situ were associated with a greater risk of subsequent invasive carcinoma. The paper by Kong et al,36 however, does not unfortunately permit further stratification of risk, sharing many of the issues of NSABP-17 trial design.23 Specifically, the effect of tumor size and resection margin width could not be examined owing to lack of standardized reporting. Hughes et al21 in their series with precise case definition, also report data suggesting that women aged <45 years are at greater risk for local recurrence than older women and that those at the greatest risk have high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ. Our current study is consistent with these findings showing a trend toward higher recurrence rates in younger women.

In summary, the current series and the series reported by Betsil et al16 provide validation of the criteria currently used to delimit small, low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ lesions. In conjunction with subsequent studies of women with ductal carcinoma in situ who underwent planned excision, these findings provide strong evidence that a limited and completely delimited DCIS can be cured successfully by excision alone. Thus approach to treatment must be based on a combination of the natural history and the extent of mammary involvement, emphasizing the need for consideration of less aggressive therapy when these lesions are limited in size, and the recurrence interval may well be beyond a reasonable life expectancy for the patient.

References

Jensen R, Page DL . Epithelial hyperplasia In: Elston CW, Ellis IO, (eds). The Breast 3rd edn. Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, UK, 1998, pp 65–89.

Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW et al. Atypical hyperplastic lesions of the female breast. A long-term follow-up study. Cancer 1985;55:2698–2708.

Tavassoli FA, Norris HJ . A comparison of the results of long-term follow-up for atypical intraductal hyperplasia and intraductal hyperplasia of the breast. Cancer 1990;65:518–529.

Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW et al. Continued local recurrence of carcinoma 15-25 years after a diagnosis of low grade ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast treated only by biopsy. Cancer 1995;76:1197–1200.

Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW et al. Intraductal carcinoma of the breast: follow-up after biopsy only. Cancer 1982;49:751–758.

Sanders ME, Schuyler PA, Dupont WD et al. The natural history of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in women treated by biopsy only revealed over 30 years of long-term follow-up. Cancer 2005;103:2481–2484.

Lester SC, Bose S, Chen YY et al. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2009;133:15–25.

Dupont WD, Page DL . Risk factors for breast cancer in women with proliferative breast disease. N Engl J Med 1985;312:146–151.

Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2005;353:229–237.

Marshall LM, Hunter DJ, Connolly JL et al. Risk of breast cancer associated with atypical hyperplasia of lobular and ductal types. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1997;6:297–301.

Shaaban AM, Sloane JP, West CR et al. Histopathologic types of benign breast lesions and the risk of breast cancer: case-control study. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:421–430.

Page DL, Anderson TJ . Diagnostic Histopathology of the Breast. Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, London, UK; Melbourne, Australia; and New York, USA, 1987.

Elston CW, Ellis IO . The Breast 3rd edn. Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, London, UK; New York, Philadelphia, SanFrancisco, USA; Sidney, Australia; Toronto, Canada, 1998.

Page DL . Special types of invasive breast cancer, with clinical implications. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:832–835.

Dupont WD . Statistical modeling for biomedical researchers: a simple introduction to the analysis of complex data 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009.

Betsill WL Jr., Rosen PP, Lieberman PH et al. Intraductal carcinoma. Long-term follow-up after treatment by biopsy alone. JAMA 1978;239:1863–1867.

Rosen PP, Braun DW Jr., Kinne DE . The clinical significance of pre-invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer 1980;46:919–925.

Collins LC, Tamimi R, Baer H et al. Risk of invasive breast cancer in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS] treated by diagnostic biopsy alone:results from the Nurses' Health Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1994;88:1083.

Ernster VL, Barclay J, Kerlikowske K et al. Incidence of and treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. JAMA 1996;275:913–918.

Glover JA, Bannon FJ, Hughes CM et al. Increased diagnosis and detection rates of carcinoma in situ of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;133:779–784.

Hughes LL, Wang M, Page DL et al. Local excision alone without irradiation for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5319–5324.

Bijker N, Peterse JL, Duchateau L et al. Risk factors for recurrence and metastasis after breast-conserving therapy for ductal carcinoma-in-situ: analysis of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Trial 10853. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:2263–2271.

Fisher ER, Dignam J, Tan-Chiu E et al. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP) eight-year update of Protocol B-17: intraductal carcinoma. Cancer 1999;86:429–438.

Lagios MD, Margolin FR, Westdahl PR et al. Mammographically detected duct carcinoma in situ. Frequency of local recurrence following tylectomy and prognostic effect of nuclear grade on local recurrence. Cancer 1989;63:618–624.

Schwartz GF, Finkel GC, Garcia JC et al. Subclinical ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Treatment by local excision and surveillance alone. Cancer 1992;70:2468–2474.

Silverstein MJ, Lagios MD, Groshen S et al. The influence of margin width on local control of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1455–1461.

Bellamy CO, McDonald C, Salter DM et al. Noninvasive ductal carcinoma of the breast: the relevance of histologic categorization. Hum Pathol 1993;24:16–23.

Bijker N, Meijnen P, Peterse JL et al. Breast-conserving treatment with or without radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma-in-situ: ten-year results of European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer randomized phase III trial 10853—a study by the EORTC Breast Cancer Cooperative Group and EORTC Radiotherapy Group. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3381–3387.

Formenti SC, Arslan AA, Pike MC . Re: Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:1723.

Wapnir IL, Dignam JJ, Fisher B et al. Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:478–488.

Correa C, McGale P, Taylor C et al. Overview of the randomized trials of radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2010;2010:162–177.

Lee DY, Lewis JL, Wexelman BA et al. The consequence of undertreatment of patients treated with breast conserving therapy for ductal carcinoma in-situ. Am J Surg 2013;206:790–797.

Guerra LE, Smith RM, Kaminski A et al. Invasive local recurrence increased after radiation therapy for ductal carcinoma in situ. Am J Surg 2008;196:552–555.

Page DL, Rogers LW . Combined histologic and cytologic criteria for the diagnosis of mammary atypical ductal hyperplasia. Hum Pathol 1992;23:1095–1097.

Vandenbussche CJ, Khouri N, Sbaity E et al. Borderline atypical ductal hyperplasia/low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ on breast needle core biopsy should be managed conservatively. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:913–923.

Kong I, Narod SA, Taylor C et al. Age at diagnosis predicts local recurrence in women treated with breast-conserving surgery and postoperative radiation therapy for ductal carcinoma in situ: a population-based outcomes analysis. Curr Oncol 2014;21:e96–e104.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NCI Grants R01 CA050468, P50 CA098131 and P30 CA068485 and by an NCATS/NIH Grant UL1 TR000445.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work was presented in part as a platform presentation at the March 2010 USCAP meeting Abstract: Modern Pathology 2010;23(supp1):71A.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sanders, M., Schuyler, P., Simpson, J. et al. Continued observation of the natural history of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ reaffirms proclivity for local recurrence even after more than 30 years of follow-up. Mod Pathol 28, 662–669 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.141

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.141

This article is cited by

-

AI analytics can be used as imaging biomarkers for predicting invasive upgrade of ductal carcinoma in situ

Insights into Imaging (2024)

-

Progress Toward Non-operative Management of Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia

Current Breast Cancer Reports (2024)

-

Molecular signatures of in situ to invasive progression for basal-like breast cancers: An integrated mouse model and human DCIS study

npj Breast Cancer (2022)

-

A deep learning model for breast ductal carcinoma in situ classification in whole slide images

Virchows Archiv (2022)

-

Precision pathology as applied to breast core needle biopsy evaluation: implications for management

Modern Pathology (2021)