Abstract

The pathogenesis of cystic nephroma of the kidney has interested pathologists for over 50 years. Emerging from its initial designation as a type of unilateral multilocular cyst, cystic nephroma has been considered as either a developmental abnormality or a neoplasm or both. Many have viewed cystic nephroma as the benign end of the pathologic spectrum with cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma and Wilms tumor, whereas others have considered it a mixed epithelial and stromal tumor. We hypothesize that cystic nephroma, like the pleuropulmonary blastoma in the lung, represents a spectrum of abnormal renal organogenesis with risk for malignant transformation. Here we studied DICER1 mutations in a cohort of 20 cystic nephromas and 6 cystic partially differentiated nephroblastomas, selected independently of a familial association with pleuropulmonary blastoma and describe four cases of sarcoma arising in cystic nephroma, which have a similarity to the solid areas of type II or III pleuropulmonary blastoma. The genetic analyses presented here confirm that DICER1 mutations are the major genetic event in the development of cystic nephroma. Further, cystic nephroma and pleuropulmonary blastoma have similar DICER1 loss of function and ‘hotspot’ missense mutation rates, which involve specific amino acids in the RNase IIIb domain. We propose an alternative pathway with the genetic pathogenesis of cystic nephroma and DICER1-renal sarcoma paralleling that of type I to type II/III malignant progression of pleuropulmonary blastoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Cystic nephroma of the kidney originally emerged as a specific entity from a group of lesions with the collective designation of unilateral multilocular cyst; one of the early references regarding unilateral multilocular cyst is by Boggs and Kimmelstiel in 1956.1 The past 50 years have provided little further insight into its histogenesis, although childhood cystic nephroma and cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma have been regarded as part of the spectrum of Wilms tumor.2, 3

The current study is based in part on the observation of an apparent familial association of cystic nephroma and the pulmonary neoplasm of childhood, pleuropulmonary blastoma.4, 5, 6 These findings were confirmed in studies from the International Pleuropulmonary Blastoma Registry (Registry), noting that ∼12% of children with a pleuropulmonary blastoma also had a cystic nephroma or a family member with cystic nephroma.7 Since the latter report, much has been learned about the genetic pathogenesis of pleuropulmonary blastoma. Using linkage analysis, Hill and associates detected heterozygous germline loss-of-function mutations of the miRNA processing gene DICER1 in 11 pleuropulmonary blastoma families; one of the individuals in this initial linkage study had a cystic nephroma.8 Subsequent analyses demonstrate that 80/122 (65.5%) children with pleuropulmonary blastoma have heterozygous germline loss-of-function DICER1 mutations (unpublished data). Tumors in the DICER1-pleuropulmonary blastoma familial tumor predisposition syndrome appear to follow a two-hit model of tumorigenesis. Analysis of pleuropulmonary blastoma tumor tissue identified deleterious somatic missense mutations in the second (normal) DICER1 allele involving very specific regions or ‘hotspots’ in the RNase IIIb domain.9 These RNase IIIb mutations, or second ‘hits’, lead to defective cleavage of the mature miRNA from the 5p arm of the miRNA hairpin, resulting in tumor-specific loss of the major subset of miRNAs in the tumors.9 These missense mutations appear to occur very early in tumorigenesis with subsequent genetic events involving p53 function and RAS pathway activation contributing to pleuropulmonary blastoma tumor progression. Similar DICER1 somatic mutations were identified in 26 of 43 (60%) Sertoli-Leydig tumors of the ovary.10 Sertoli-Leydig tumors are seen in the DICER1-pleuropulmonary blastoma familial tumor predisposition syndrome.11

The present report documents our findings of DICER1 mutations in a cohort of 20 cystic nephromas and 6 cystic partially differentiated nephroblastomas that were selected independently of a familial association with pleuropulmonary blastoma and also includes a clinicopathologic review of 34 individuals with cystic nephroma from the Registry. In addition, we describe four cases of a primary sarcoma arising in cystic nephroma that have remarkably similar histologic features to the solid sarcomatous patterns of type II/III pleuropulmonary blastoma. This genetic analysis of cystic nephroma provides some histogenetic and nosologic clarity while at the same time prompting new questions about the biology and natural history of cystic nephroma.

Materials and methods

Patients/Samples

DNA from 16 and 8 snap frozen cystic nephroma and cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma, respectively, and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue scrolls on an additional two cystic nephromas were obtained from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network from children enrolled on Children’s Oncology Group protocols from 2007 to 2010. Pathology reports without identifying information were obtained for each specimen and included age, sex, site of tissue and a pathologic description. No additional patient history or follow-up was provided. Access to Cooperative Human Tissue Network samples was approved through an application submitted to the Children’s Oncology Group Renal Tumor Biology Section, and this research was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC, USA. Paraffin blocks from an additional 11 cystic nephromas and four renal sarcomas were obtained from the Registry or from the authors’ consultation files (DAH, LPD, PF, EP). For all formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples, four 10-micron scrolls were prepared from a tumor block. Following paraffin removal, DNA was extracted using the Maxwell 16 Formalin-Fixed Paraffin Embedded Tissue LEV DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) on the Maxwell 16 Instrument (Promega). DNA quality and quantity was assessed using a Nanodrop (ThermoFisher, Wilmington, DE, USA) and Qubit (Qubit 2.0, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), respectively.

Next Generation Sequencing and Analysis

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded and fresh DNA samples were sequenced with the Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine (Life Technologies) using standard protocols. A custom multiplex polymerase chain reaction panel was designed for the coding regions of DICER1 with an average amplicon length less than 200 base pairs (Custom Ampliseq, Life Techologies). The initial polymerase chain reaction amplification was performed on 10 ng of starting DNA. The resulting amplicons were then barcoded and ligated to adaptors (Ion Ampliseq Library kit 2.0, Life Technologies). Templates were prepared using the Ion Personal Genome Machine Template OT2 200 prep kit and the One Touch 2 system (Life Technologies). Sequencing was performed on a 318 chip (ION Sequencing 200 kit V2, Life Technologies) with an average of six samples per chip plus one each positive and negative control samples to achieve an average depth of coverage of 3000 filtered reads. Signal processing, mapping and quality control was performed with Torrent Suite v.3.4.1 (Life Technologies). Variant calls were made using Torrent Variant Caller Plugin 3.4 choosing somatic mutation workflow and default settings. BAM files containing raw reads were reviewed using Integrative Genomics Viewer http://www.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/home.12, 13 Variants were annotated with Ion Reporter Software and named using HUGO nomenclature for DICER1 transcript NM_177438.2.14 Nonsense and frameshift mutations were classified as ‘allele loss of function.’ Missense variants affecting codons for amino acids 1705, 1709, and 1809, 1810, 1813, and 1814 were classified as ‘hotspot mutations.’ Allele frequency was recorded for each variant. Coverage information was recorded for each of the cases with normal sequence at all hotspot bases. SIFT was used to assess the potential significance of predicted novel amino-acid substitutions outside of the hotspot regions http://sift-dna.org.15, 16

Sanger Sequencing

For the DNA samples derived from fresh/frozen tumors, high throughput Sanger sequencing was performed on all coding exons and intron–exon junctions in the DICER1 gene (BeckmanCoulter Genomics, Danvers, MA, USA). The sequence traces were assembled and the chromatograms were scanned for variants using Mutation Surveyor version 4.0.6 (Soft Genetics, State College, PA, USA). For two formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded sarcoma cases, primer pairs for smaller amplicons containing the hotspot sequences were used: Primer pair 1: Forward: 5′-tggggatcagttgctatgtg-3′ and Reverse: 5′-CGGGTCTTCATAAAGGTGCT-3′; Primer pair 2: Forward: 5′-tggactgcctgtaaaagtgg-3′ and Reverse: 5′-ATGTAAATGGCACCAGCAAG-3′.

Results

Patient Characteristics of the Cooperative Human Tissue Network Cohort

Review of the microscopic descriptions from the pathology reports for two cases submitted as cystic partially differentiated neoplasm to the Cooperative Human Tissue Network bank indicated no primitive nephroblastic elements. Central review was performed by the pathologist (EP) with access to pathologic slides but blinded to genetic data who indicated that these tumors did not contain primitive nephroblastic elements, and thus are considered cystic nephromas in the analysis. The 20 patients with cystic nephromas ranged from 1 month to 106 months at diagnosis (median 16 months) and there were 11 females and 9 males. Ten tumors involved the right kidney, eight involved the left and for two the side was unknown. The six patients with cystic partially differentiated nephroblastomas ranged in age from 4 to 14 months (median 7 months). Four of six patients were female. Four of the six tumors were right sided.

DICER1 Sequencing of the Cooperative Human Tissue Network Cohort

The sequencing results of the Cooperative Human Tissue Network cohort are provided in Table 1. Allelic loss of function DICER1 mutations were seen in 14/20 (70%) cystic nephromas and 0/6 (0%) cystic partially differentiated nephroblastomas, respectively. The loss of function mutations included nine insertion-deletions with frameshifts, four nonsense mutations and one c.2437-1G>A substitution involving the canonical splice site of intron 18-exon19. Each of these mutations result in premature truncation of the DICER1 protein (deleterious truncating mutations) An additional loss of function variant in one of the cystic nephromas was three bases proximal to the intron 25-exon 26 junction c.5527+3A>G (intron 25) (Table 1). No RNA was available to determine if this variant would disrupt normal splicing. Germline DNA was not initially requested at the start of this study; hence, we were unable to determine whether these loss of function mutations were germline or somatic. (However, the majority (80%) of loss of function mutations are germline in the pleuropulmonary blastoma).9

Deleterious missense DICER1 mutations affecting one of the six amino-acid hotspots were seen in 18/20 (90%) cystic nephromas and 0/6 cystic partially differentiated nephroblastomas, respectively (Fisher exact test two-tailed P=0.0001). The most frequent amino acid affected by mutations was amino acid 1813 (nine cases). Mutations altering amino acids 1705 and 1709 were seen in three cases each. There were two mutations affecting amino acid 1809 and one affecting amino acid 1810.

Eleven of 14 (79%) deleterious truncating mutations had allele frequencies between 43 and 54% which would be within range of the expected 50% for a heterozygous germline mutation. One truncating mutation had a low frequency of 15%, which may indicate either loss of this allele in the tumor was the second event (this tumor also had 38% allele frequency hotspot) or the truncating mutation in this allele was accompanied by duplication of the hotspot missense mutant allele (see below). The allele frequencies for hotspot missense mutations were widely variable ranging from 1 to 53% (median 23%), which likely reflects the variability in mesenchymal content of each sampled tissue, as it would be unexpected in a cystic nephroma sample to have 100% tumor cellularity given the commonplace presence of inflammatory cells, fibroblasts and normal renal parenchyma. Thus, in the one case of cystic nephroma with 53% hotspot allele frequency, it is likely that there has been gain of the hotspot missense allele, which has been described in pleuropulmonary blastoma.9 Sanger sequencing confirmed next generation sequencing results with the exception of variants with allele frequencies less than 10%.

Patient Characteristics of Cystic Nephromas and Wilms Tumors in Registry Families

The Registry has collected and analyzed clinical, pathological and treatment data on 375 children with pleuropulmonary blastoma and additional patients and family members with related conditions.5 To date, thirty-four cases of cystic nephroma have been identified including 19 cases occurring in children with pleuropulmonary blastoma, 8 in family members of children with pleuropulmonary blastoma and 7 in children who presented with cystic nephroma alone (Table 2). In this group, 18 patients had DICER1 testing performed and 13/18 (72%) had a loss of function (truncating) germline mutation. The median age at diagnosis was 19 months, (range 0–54 months), with one outlier diagnosed at 179 months. Available information on those cases of cystic nephroma disclosed that 74% were unilateral and 26% were bilateral. Treatment included complete nephrectomy in most cases (n=18), partial nephrectomy (n=8), one left nephrectomy with contralateral partial nephrectomy, and two patients required bilateral nephrectomy followed by transplantation.17 With a median follow-up of 4.6 years (range 0–47 years), two patients died (2/34 or 6%) and both from the progression of their pleuropulmonary blastomas. Of the 34 patients with cystic nephromas, 6 (18%) had type II pleuropulmonary blastoma and 13 (39%) had a type I pleuropulmonary blastoma and/or radiographic evidence of lung cysts. One case with bilateral cystic nephromas diagnosed at 11 months of age had a left nephrectomy with progressive enlargement of cysts in the right kidney; this patient developed a cystic (type I) pleuropulmonary blastoma at 19 months of age requiring chemotherapy. The growth of the renal cysts appeared to be arrested during the chemotherapy. Clinical follow-up at 4.5 years indicates that this patient remains healthy with stable renal cysts and normal renal function.

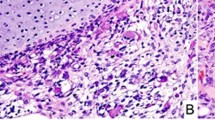

The Registry cohort includes four cases of Wilms tumor; one in a child who later developed pleuropulmonary blastoma and the remaining three in relatives of children who had pleuropulmonary blastomas (mother, brother, and great uncle). Of note, the mother with Wilms tumor in childhood did not have a DICER1 mutation, whereas her child with pleuropulmonary blastoma inherited her germline truncating DICER1 mutation from the paternal side. Histologic review of the Wilms tumor from the child who subsequently developed pleuropulmonary blastoma showed an unusual multipatterned neoplasm with blastema, cartilage, differentiated skeletal muscle, anaplasia, and primitive epithelial tubules (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry for WT1 showed strong nuclear staining in the epithelial components. Next generation sequencing on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue from the pleuropulmonary blastoma in this child identified a germline loss of function DICER1 mutation (c.1732dupA; p.Thr578Asnfs*6) and a somatic missense mutation (p.E1813D). Similar analysis of tissue from the Wilms tumor detected the loss of function DICER1 mutation c.1732dupA but did not identify a missense mutation in a common hotspot region. Follow-up Sanger sequencing with small primers designed for hotspot mutation detection was also negative. No slides or DNA were available from the other two Registry cases.

Unusual Wilms tumor in patient with germline DICER1 mutation and subsequent PPB. (a) Sheets of loose primitive blastemal cells and nodules of cartilage, (b) Primitive cartilage nodule emerging from primitive mesenchyme on left; (c) primitive spindled cells with skeletal muscle differentiation; (d) array of primitive tubules resembling seen primitive tubules in classic Wilms tumor (H&E; original magnification × 200 (a–d).

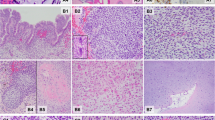

Pathology of Four Cystic Nephroma-Associated Renal Sarcomas

Over the past year, the Registry has had the opportunity to review four examples of renal sarcomas associated with cystic nephroma.

Case 1

A 15-year-old male had a past history of ‘multifocal cystic adenomatoid malformations’ of the right and left lungs at age of 7 months, which was followed by bilateral cystic nephromas at 18 months of age treated with wedge excisions. He was well until 10 years of age when a left renal mass was detected and a nephrectomy was performed. This neoplasm was a high-grade sarcoma with blastema, spindle cell and anaplastic elements seemingly arising beneath the renal pelvic urothelium (Figure 2). Vascular invasion was identified within the renal hilum. No primitive tubular/epithelial components were identified. Residual cystic nephroma was seen adjacent to the malignant component. The tumor was interpreted as an ‘anaplastic Wilms tumor.’ At age 13 years and again at 15 years, he presented with recurrent abdominal masses with a high-grade sarcomatous morphology. Material was not available for DICER1 testing.

Malignant transformation of cystic nephroma in a 10 year-old boy. (a) Low power view of complex cystic spaces and variable stromal cellularity; (b) medium power view of cyst septa lined by plump, cuboidal, ‘hobnail,’ epithelium with subepithelial layer of primitive cells (cambium layer). This pattern is remarkably similar to the Type I, cystic PPB. (c, d) High power views of atypical, primitive cells beneath the epithelium; (e, f) recurrent solid tumor with spindle cell sarcomatous and anaplastic patterns ((H&E; original magnification × 100 (a), × 200 (b, e); × 400 (c, d, f)).

Case 2

A 20-year-old female was found to have a 6.8-cm multilocular cystic renal mass, which was resected in a piecemeal manner. Multiple cysts lined by cuboidal/hobnail epithelium with a subepithelial condensation of primitive mesenchymal spindle cells with a cambium layer-like appearance were the histologic features (Figure 3). Focal areas with undifferentiated spindle cells with marked atypia were also present. Approximately 11 months later, omental and cul de sac masses were discovered, these masses had high-grade anaplastic sarcomatous features similar to the atypical areas seen in the renal cystectomy specimen. Mutation analysis was performed on frozen tumor tissue and showed DICER1 nonsense mutation in exon 14 (c.2233C>T; p. Arg745*) and a missense hotspot mutation (c.5437G>A; p.Glu1813Lys). There was also a TP53 mutation in exon 7 (c.731G>A; p.G244D) affecting the transactivational domain and predicted to be deleterious by SIFT. The TP53 variant allele frequency was 97% suggesting loss of the wild-type allele. Cytogenetics showed a complex karyotype with multiple numerical and structural abnormalities including allelic loss of chromosome 17.

Malignant transformation of cystic nephroma in a 20 year-old woman. (a) Low power view of renal mass with variably sized cystic spaces and focal areas of increased stromal cellularity; (b) medium power view of cyst with plump cuboidal epithelium and loose subepithelial mesenchyme; (c) medium power view of septa lined by plump cuboidal epithelium and subepithelial collection of primitive cells (cambium layer); (d) recurrent solid tumor with diffuse anaplasia ((H&E; original magnification × 100 (a), × 400 (b, d); × 200 (c)).

Case 3

A 26-month-old female with a 940 gram cystic and solid renal neoplasm had been reported previously as a dedifferentiated cystic nephroma with malignant mesenchymoma.18 The mother had noted an abdominal mass 3 months before surgery, but also stated that an increased abdominal girth was present for approximately a year. The main component of the tumor was multilocular, with cysts ranging from 0.1 to 3 cm in diameter. The cysts were lined by flattened, cuboidal or hobnail epithelium with thin septa of varying cellularity. There were multiple subepithelial areas of primitive cells or spindle cells without expansile tumor growth. A 7 × 5 × 4 cm3 solid area was composed of primitive skeletal muscle, small primitive embryonal cells, malignant cartilage, and anaplasia (Figure 4). Immunohistochemistry for WT1 showed cytoplasmic staining in the primitive embryonal and skeletal muscle components. No primitive tubular/epithelial elements were seen. She was alive without disease 18 years after diagnosis. DICER1 sequencing on both germline DNA and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue did not identify either a deleterious loss of function mutation or a hotspot somatic missense mutation.

Malignant transformation of cystic nephroma in a 26-month-old child. (a) Low power view showing multiple rounded cysts with increased septal cellularity; (b) high power view showing subepithelial spindle cell proliferation; (c) nodules of primitive cells intermixed with loose rhabdomyosarcomatous tumor tissue; (d) area with more advanced skeletal muscle differentiation; (e, f) nodules of malignant cartilage in background of anaplastic sarcoma (H&E; original magnification × 100 (a), × 400 (b, d, e, f), × 200 (c)).

Case 4

A 21-month-old girl had a 6.6 cm cystic and solid mass of the left kidney, which was composed of multiple cysts lined by cuboidal/hobnail epithelium with loose subepithelial mesenchyme without overtly sarcomatous features, but in adjacent areas there was a spindle cell sarcoma pattern with anaplasia and pleomorphism (Figure 5). No primitive tubular or other epithelial elements were seen. Immunohistochemically, the immature mesenchyme and solid sarcomatous foci were reactive for desmin, and there was no nuclear WT1 expression. DICER1 testing on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissue identified a c.5427G>A; G1809R somatic missense mutation.

Renal sarcoma with cystic nephroma-like cysts in a 21 month old child. (a) Low power view of large cystic structures with loose, pale subepithelial zone; (b, c) medium power view of cysts adjacent to solid sarcomatous areas; (d) high-grade spindle cell sarcoma; (e) anaplastic tumor cells with markedly atypical enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei and cytoplasmic hyaline globules; (f) desmin immunohistochemistry highlighted cells in the anaplastic areas. (H&E; original magnification × 100 (a), × 200 (b, c), × 400 (d, e); anti-desmin immunostain × 400 (f)).

Discussion

Cystic and multicystic lesions of the kidney encompass a broad pathogenetic spectrum ranging from inherited, developmental to neoplastic processes. Circumscribed multicystic lesions in the kidney in the pediatric age group include cystic nephroma and cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma as representatives of the Wilms tumor spectrum.2, 3, 19 Although both cystic nephroma and cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma are indistinguishable on gross examination, the presence of microscopic ‘immature’ nephroblastic elements differentiates the latter from cystic nephroma.2, 19

There has been considerable discussion in the recent past literature about the histogenetic relationship between cystic nephroma and another multicystic tumor of the kidney, mixed epithelial, and stromal tumor.20, 21 Recent pathologic and molecular studies have served to promote the idea that these two cystic neoplasms are closely related entities on the basis of morphology, immunohistochemistry, and gene expression; the multicystic architecture and the approximation of the epithelial lining of the cysts and the underlying septal stroma are the basic morphologic similarities.20, 21 There is a proposed unifying designation for these tumors as ‘renal epithelial and stromal tumor.’20 An alternative position states that ‘adult cystic nephroma is distinct from pediatric cystic nephroma, which is considered to be part of the spectrum of Wilms.’21

The present study is based upon the observation of the association between cystic nephroma and pleuropulmonary blastoma in children especially in light of heterozygous germline mutations in DICER1 in affected kindreds.8, 22 It has become apparent that cystic nephroma and the purely cystic (type I) pleuropulmonary blastoma are morphologically similar in their composition of epithelial-lined cysts and subepithelial mesenchyme as well as occurring primarily in children two years of age or less.23 Mouse models with conditional biallelic DICER1 ablation in distal lung epithelium and ureteric bud epithelium have recapitulated the human phenotype of cystic (type I) pleuropulmonary blastoma and cystic nephroma, respectively.24, 25, 26 One notable difference between cystic nephroma and pleuropulmonary blastoma is the seemingly disproportionate risk for sarcomatous transformation in the case of cystic (type I) pleuropulmonary blastoma.27 This potential for cystic or type I pleuropulmonary blastoma to progress to a high-grade, multipatterned sarcoma in the type II and III pleuropulmonary blastomas is well established, but it is not a constant feature and may in fact occur in only a small proportion of cystic (type I) pleuropulmonary blastoma in DICER1 mutation-positive individuals.23 If malignant transformation in cystic pleuropulmonary blastoma is less common than we have supposed that cystic nephroma and pleuropulmonary blastoma are so closely related in their genetic pathogenesis, then we should not be surprised that a small fraction of cystic nephromas are capable of sarcomatous transformation or progression. If this model of progression of cysts to sarcoma is valid, renal sarcomas arising in association with cystic nephromas should be high-grade, anaplastic and multipatterned, and indistinguishable in most respects from the solid, sarcomatous component of pleuropulmonary blastoma.23, 27 It was our premise that a DICER1 cystic nephroma may have a sarcomatous counterpart like pleuropulmonary blastoma. Similar to the initial reporting of cases of pleuropulmonary blastoma in the literature before 1988, we believe that such renal sarcomas have been reported under a variety of appellations.28 One such report of 20 cases of anaplastic sarcoma of the kidney is particularly provocative; 10 of the patients in this report were five years of age or less at diagnosis.29 A multiloculated cystic component with the features of cystic nephroma was present in 7 of the 20 cases. These authors appreciated that the sarcomatous pattern in their cases showed a ‘similarity to the pleuropulmonary blastoma.’29 Likewise, Faria and Zerbini also noted that the sarcoma arising in their case of a cystic nephroma resembled the pleuropulmonary blastoma.18 Other categories including embryonal sarcoma or embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of kidney may also include some DICER1 sarcomas.30, 31, 32 Certainly there is sufficient morphologic overlap with anaplastic Wilms tumor that a few of these high-grade renal neoplasms may have been regarded as variants of anaplastic Wilms tumor. Identification of a residual cystic nephroma component with or without a cambium layer would be a clue to the diagnosis if present, but, given the experience with pleuropulmonary blastoma, solid or type III pleuropulmonary blastomas do not have residual cystic elements and possibly not all pleuropulmonary blastomas progress from a cystic stage, but this progression from a cystic stage to a solid primitive sarcoma has been observed in a number of Registry cases.

On the basis of (1) the identification of DICER1 RNase IIIb missense mutations in 18/20 (90%) cystic nephromas, but in none of the cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma (P=0.0001) is one compelling point;33, 34 (2) the younger median age of cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma in our group of cases and in a larger series (median age 12 months) than the age of children with cystic nephroma (median age 18 months), in contrast to age-linked multi-step genetic progression such as seen in pleuropulmonary blastoma,2, 19 and (3) the striking morphological differences between the sarcomas associated with cystic nephroma and typical Wilms tumor, we have concluded that cystic nephroma in children is not part of the same pathogenetic spectrum as cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma and Wilms tumor as generally accepted in the literature. Joshi and Beckwith19 have defined cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma as a cystic lesion similar in appearance to cystic nephroma, but containing ‘immature’ blastemal elements; however, they also note that there are ‘gray-zone’ tumors with poorly differentiated stroma and no blastemal cells. We propose that some of these gray-zone tumors lacking primitive nephrogenic elements may actually be cystic nephromas, which have undergone malignant progression in a manner similar to the cystic (type I) pleuropulmonary blastoma.27

Recently, a potential relationship between DICER1 mutations and Wilms tumor has been suggested.2, 35, 36 As an organ-based embryonal tumor with many features similar to pleuropulmonary blastoma, a pathogenetic link between pleuropulmonary blastoma and Wilms tumor would be compelling. However, unlike pleuropulmonary blastoma, familial Wilms tumor is quite uncommon (only 1-2% of all cases) and has been linked to mutations/deletions in WT1 (11p13), FWT1 (17q12) and FWT2 (19q13) but not 14q 32.13 where DICER1 is located.37 Three studies to date have reported results on DICER1 testing in individuals with Wilms tumor; one of these found no DICER1 mutations in the germline DNA from 50 patients.22 The second study identified a truncating mutation in DICER1 in germline DNA from 1 (0.4%) of 243 patients with Wilms tumor.35 Interestingly, this patient later developed bilateral Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors of the ovary, one of the extrapulmonary neoplasms in the DICER1—pleuropulmonary blastoma familial tumor predisposition syndrome.11 Wu and colleagues36 performed whole gene DICER1 sequencing on tumor tissue from 120 sporadic Wilms tumor and targeted sequencing of the RNase IIIa and IIIb domains on 71 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded Wilms tumors; five missense or deleterious mutations in four Wilms tumors (2.6%) were identified. Upon closer review, only one of these four Wilms tumor had detectable biallelic DICER1 variants; this case (case N) had two somatic mutations in trans involving the RNase IIIb domain (c.5438A>G and c.5452G>A); c.5438 A>G affects a common hotspot amino acid E1813G seen in pleuropulmonary blastoma and cystic nephroma.36 These authors noted the presence of clones from this tumor with neither mutation suggesting that these mutations were subclonal, occurring later in tumorigenesis. The other three cases described contained a benign change p.I110V (case X), a single 5330T>A; p.L1777H involving RNase IIIb domain (case M), and a germline missense single-nucleotide polymorphism c.2614G>A;p.A872T (rs149242330; MAF 0.009) in a patient with biallelic WT gene deletion/mutation and WAGR syndrome (case C). It would be difficult to ascertain if the heterozygous DICER1 mutation was additive to the WT1 gene abnormalities in the development of this Wilms tumor in this child.

The Registry has identified one child with a Wilms tumor who subsequently developed pleuropulmonary blastoma and three family members of children with pleuropulmonary blastoma. One family member with a Wilms tumor did not have a DICER1 mutation, whereas her child with pleuropulmonary blastoma inherited the germline DICER1 mutation from the paternal side. This case highlights the need for caution in presuming that all examples of a particular neoplasm within a pleuropulmonary blastoma family are necessarily attributable to DICER1 mutations.38 Only one example of pleuropulmonary blastoma associated Wilms tumor was reviewed by Registry pathologists; this renal neoplasm had some unusual histologic features for a Wilms tumor but showed nuclear positivity for WT1. Sequencing of this tumor identified the germline loss of function mutation, but hotspot missense mutations were not identified despite adequate coverage of those regions. Photomicrographic documentation of DICER1-related Wilms tumor was not provided in the other large studies;22, 36 however, the morphologic characterization of the Wilms tumor in the report of Slade et al35 was described as having the typical features of Wilms tumor (Personal communication, Kathy Pritchard-Jones, 2013). The three hereditary Wilms tumors described by Foulkes and Wu were described as ‘triphasic’; one tumor had anaplasia.22, 38 Pathologic review of additional cases may provide insight as to whether or not DICER1-mutated Wilms tumors are morphologically unique. It is notable that only two in five Wilms tumors with loss of function DICER1 mutations also had somatic RNase IIIb mutations.36 Additional studies in this area are necessary to obtain a full understanding of the role of DICER1 mutations in the development of Wilms tumor.

Pleuropulmonary blastoma and cystic nephroma represent a spectrum of abnormal organogenesis affecting both the lung and kidney, respectively. The genetic analyses presented here confirm that DICER1 mutations have a major genetic role in the pathogenesis of cystic nephroma in children. Further, cystic nephroma and pleuropulmonary blastoma have a similar DICER1 truncating and ‘hotspot’ missense mutation rates, which involve specific amino acids in the RNase IIIb domain.9 Rather than cystic nephromas in children as representing the benign end of the Wilms tumor spectrum, we propose an alternative pathway with the genetic pathogenesis of cystic nephroma and renal sarcoma following a similar model of cystic (type I) pleuropulmonary blastoma to the sarcomatous type II/III tumors.23, 27 Three of the four renal sarcomas described here showed clinical or genetic manifestations of the DICER1 syndrome and we would propose naming this entity ‘DICER1 renal sarcoma.’

Although most children with cystic nephroma in the Registry cohort did very well, two children died of pleuropulmonary blastoma and two others required bilateral nephrectomies and renal transplantation at 9 and 42 months of age.17 We only have long-term follow-up for one of the children with renal sarcomas described here, but we anticipate given the genetic and morphologic similarities to cystic and solid pleuropulmonary blastoma that the prognosis and response to therapy may also be similar. Review of additional cases with detailed clinical and genetic information would be informative.

Although the traditional approach to a child with a diagnosed cystic nephroma is to forego chemotherapy,33 rapidly growing, bilateral cysts in an infant present a management challenge. We have observed in one patient treated with chemotherapy for cystic (type I) pleuropulmonary blastoma in whom the progressive growth of bilateral renal cysts was arrested, averting the need for transplantation. While this is only a single case, it may suggest a beneficial role for chemotherapy; however, there is insufficient data at the present to warrant any therapeutic recommendations.

The presence of cystic neprhoma or renal sarcoma in a child or young adult should alert the clinician to the possibility of a germline mutation in DICER1 and the associated risk for pleuropulmonary blastoma and other associated conditions in the proband and/or family members. Appropriate genetic counseling and testing should be offered to the potential proband and family, and screening for lung lesions of a cystic or solid nature should be considered based on age and DICER1 testing.38 Similarly, children diagnosed with pleuropulmonary blastoma or DICER1 mutation should have serial periodic ultrasound evaluations of the kidneys as cystic nephroma may grow rapidly and early intervention may limit the damage to normal renal parenchyma. Unlike in the case of pleuropulmonary blastoma, there are no current recommendations as to the frequency and longevity of imaging studies in the case of cystic nephroma and/or subsequent development of renal sarcomas within cystic nephroma. The renal sarcomas appear to have a broader age range at diagnosis than pleuropulmonary blastoma. The risk for transformation or progression, responsiveness to chemotherapy and ultimate outcome are all unknown. To better understand this disease and to develop appropriate education and screening guidelines for individuals and families, we encourage our pathology and clinical colleagues to refer cases to the renal tumor biology studies of the Children’s Oncology Group and the longitudinal study of DICER1—pleuropulmonary blastoma tumor predisposition study in progress at the National Cancer Institute.39

References

Boggs LK, Kimmelstiel P . Benign multilocular cystic nephroma: Report of two cases of so-called multilocular cyst of the kidney. J Urol 1956;76:530–541.

Joshi VV, Banerjee AK, Yadav K et al. Cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma: a clinicopathologic entity in the spectrum of infantile renal neoplasia. Cancer 1977;40:789–795.

Murphy WM, Grignon DJ, Perlman EJ . Tumors of the kidney, bladder and related urinary structures. Washington DC. American Registry of Pathology 2004;1:47–49.

Delahunt B, Thomson KJ, Ferguson AF et al. Familial cystic nephroma and pleuropulmonary blastoma. Cancer 1993;71:1338–1342.

Priest JR, Watterson J, Strong L et al. Pleuropulmonary blastoma: a marker for familial disease. J Pediatr 1996;128:220–224.

Bal N, Kayaselcuk F, Polat A et al. Familial cystic nephroma in two siblings with pleuropulmonary blastoma. Pathol Oncol Res 2005;11:53–56.

Boman F, Hill DA, Williams GM et al. Familial association of pleuropulmonary blastoma with cystic nephroma and other renal tumors: A report from the International Pleuropulmonary Blastoma Registry. J Pediatr 2006;149:850–854.

Hill DA, Ivanovich J, Priest JR et al. DICER1 mutations in familial pleuropulmonary blastoma. Science 2009;325:965.

Pugh TJ, Yu W, Yang J et alProgressive biallelic loss of TP53 is associated with progression of pleuropulmonary blastoma initiated by germline loss and somatic mutation of DICER1. American Association of Cancer Researchers Annual Meeting, 2013 Washington, DC, USA.

Heravi-Moussavi A, Anglesio MS, Cheng SW et al. Recurrent somatic DICER1 mutations in nonepithelial ovarian cancers. N Engl J Med 2012;366:234–242.

Schultz KA, Pacheco MC, Yang J et al. Ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors, pleuropulmonary blastoma and DICER1 mutations: a report from the International Pleuropulmonary Blastoma Registry. Gynecol Oncol 2011;122:246–250.

Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP . Integrative genomics viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Briefing Bioinformatics 2013;14:178–192.

Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W et al. Integrative Genomics Viewer. Nat Biotechnol 2011;29:24–26.

Seal RL, Gordon SM, Lush MJ et al. Genenames.org: the HGNC resources in 2011. Nucleic Acids Res 2011;39 (Database issue):D514–D519.

Ng PC, Henikoff S . Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res 2001;11:863–874.

Sim NL, Kumar P, Hu J et al. SIFT web server: predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40 (Web Server issue):W452–W457.

Shaheen IS, Fitzpatrick M, Brownlee K et al. Bilateral progressive cystic nephroma in a 9-month-old male infant requiring renal replacement therapy. Pediatr Nephrol 2010;25:1755–1758.

Faria PA, Zerbini MC . Dedifferentiated cystic nephroma with malignant mesenchymoma as the dedifferentiated component. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med 1996;16:1003–1011.

Joshi VV, Beckwith JB . Multilocular cyst of the kidney (cystic nephroma) and cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma. Terminology and criteria for diagnosis. Cancer 1989;64:466–479.

Turbiner J, Amin MB, Humphrey PA et al. Cystic nephroma and mixed epithelial and stromal tumor of kidney: a detailed clinicopathologic analysis of 34 cases and proposal for renal epithelial and stromal tumor (REST) as a unifying term. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:489–500.

Zhou M, Kort E, Hoekstra P et al. Adult cystic nephroma and mixed epithelial and stromal tumor of the kidney are the same entity. Molecular and histologic evidence. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:72–80.

Bahubeshi A, Bal N, Rio Frio T et al. Germline DICER1 mutations and familial cystic nephroma. J Med Genet 2010;47:863–866.

Hill DA, Jarzembowski JA, Priest JR et al. Type I pleuropulmonary blastoma: pathology and biology study of 51 cases from the International Pleuropulmonary Blastoma Registry. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:282–295.

Harris KS, Zhang Z, McManus MT et al. Dicer function is essential for lung epithelium morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:2208–2213.

Nagalakshmi VK, Ren Q, Pugh MM et al. Dicer regulates the development of nephrogenic and ureteric compartments in the mammalian kidney. Kidney Int 2011;79:317–330.

Pastorelli LM, Wells S, Fray M et al. Genetic analyses reveal a requirement for Dicer1 in the mouse urogenital tract. Mamm Genome 2009;20:140–151.

Priest JR, McDermott MB, Bhatia S et al. Pleuropulmonary blastoma: a clinicopathologic study of 50 cases. Cancer 1997;80:147–161.

Manivel JC, Priest JR, Watterson J et al. Pleuropulmonary blastoma. The so-called pulmonary blastoma of childhood. Cancer 1988;62:1516–1526.

Vujanić GM, Kelsey A, Perlman EJ et al. Anaplastic sarcoma of the kidney: a clinicopathologic study of 20 cases of a new entity with polyphenotypic features. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;10:1459–1468.

Delahunt B, Beckwith JB, Eble JN et al. Cystic embryonal sarcoma of kidney: a case report. Cancer 1998;82:2427–2433.

Sola JE, Cova D, Casillas J et al. Primary renal botryoid rhabdomyosarcoma: diagnosis and outcome. J Pediatr Surg 2007;42:e17–e20.

Raney B, Anderson J, Arndt C et al. Primary renal sarcomas in the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group (IRSG) experience, 1972–2005: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008;51:339–343.

Luithle T, Szavay P, Furtwangler R et al. SIOP/GPOH Study Group. Treatment of cystic nephroma and cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma—a report from the SIOP/GPOH study group. J Urol 2007;177:294–296.

van den Hoek J, de Kriger R, van de Ven K et al. Cystic nephroma, cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma and cystic Wilms tumor in children: a spectrum with therapeutic dilemmas. Urol Int 2009;82:65–70.

Slade I, Bacchelli C, Davies H et al. DICER1 syndrome: clarifying the diagnosis, clinical features and management implications of a pleiotropic tumour predisposition syndrome. J Med Genet 2011;48:273–278.

Wu M, Sabbaghian N, Xu B et al. Biallelic DICER1 mutations occur in Wilms tumours. J Pathol 2013;230:154–164.

Foulkes WD, Bahubeshi A, Hamel N et al. Extending the phenotypes associated with DICER1 mutations. Hum Mutat 2011;32:1381–1384.

Hill DA, Doros L, Schultz KA et al. DICER1 syndrome disorders In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, et al (eds). Gene Reviews (Internet). Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle, 1993–2014 (in press, 2014) Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1116.

DICER1-related PPB studydceg.cancer.gov/research/clinical-studies/dicer1-ppb-study.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grants U10 CA98543 and U24 CA114766 to the Children’s Oncology Group. Tissue samples were provided by the Cooperative Human Tissue Network that is funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Other investigators may have received samples from these same tissues. Dr Hill, Doros and Dr Rossi were supported in part by NCI R01CA143167, an American Society of Clinical Oncology Young Investigator Award (LD), The Parson’s Foundation (DAH) and a grant from Hyundai Hope on Wheels. We thank the many physicians and families who contribute time and tissues that facilitate research, in particular the members of the Renal Tumor Biology Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Doros, L., Rossi, C., Yang, J. et al. DICER1 mutations in childhood cystic nephroma and its relationship to DICER1-renal sarcoma. Mod Pathol 27, 1267–1280 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.242

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.242

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multilocular cystic nephroma in an adult: a diagnostic quandary

CEN Case Reports (2024)

-

Genomic characterization of DICER1-associated neoplasms uncovers molecular classes

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Non-Wilms' renal tumors in children: experience with 139 cases treated at a single center

BMC Urology (2022)

-

DICER1 tumor predisposition syndrome: an evolving story initiated with the pleuropulmonary blastoma

Modern Pathology (2022)

-

Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterine corpus: a clinicopathological and molecular analysis of 21 cases highlighting a frequent association with DICER1 mutations

Modern Pathology (2021)