Abstract

A form of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis with lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing changes and increased numbers of IgG4-positive plasma cells has recently been reported in the literature. These histopathological features suggest that this subtype of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis may be closely related to IgG4-related disease. Therefore, this unique form of IgG4-related Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which is referred to as IgG4 thyroiditis, has its own clinical, serological, and sonographic features that are distinct from those associated with non-IgG4 thyroiditis. IgG4 thyroiditis shares similarities with the well-known fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis; however, the detailed histopathological features of IgG4 thyroiditis have not been well established. Based on immunostaining results, 105 patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis were divided into an IgG4 thyroiditis group (n=28) and a non-IgG4 thyroiditis group (n=77). As in our previous reports, IgG4 thyroiditis was associated with a patient population of a younger age, a lower female-to-male ratio, rapid progression, higher levels of thyroid autoantibodies, subclinical hypothyroidism, and diffuse sonographic echogenicity. Histopathologically, this group revealed severe lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, dense stromal fibrosis, marked follicular cell degeneration, numerous micro-follicles, and notable giant cell/histiocyte infiltration. Importantly, the IgG4-related group did not completely overlap with fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Four cases (14%) in the IgG4 thyroiditis group presented only mild fibrosis in the stroma, whereas 29 cases (38%) in the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group met the diagnostic criteria for fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Furthermore, we observed three patterns of stromal fibrosis in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: interfollicular fibrosis, interlobular fibrosis, and scar fibrosis. The IgG4 thyroiditis group was significantly associated with the presence of predominant interfollicular fibrosis. In conclusion, IgG4 Hashimoto’s thyroiditis presents histopathological features quite distinct from its non-IgG4 counterpart.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis or struma lymphomatosa, was first described by Hakaru Hashimoto.1 It is now recognized as an autoimmune thyroid disease that is characterized by high titers of circulating antibodies to thyroid peroxidase and thyroglobulin. The typical microscopic changes of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis usually consist of lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and lymphoid follicle formation with well-developed germinal centers. However, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is not a histopathologically homogeneous lesion. Several subtypes of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which present with clinicopathological features that are quite distinct from that of typical Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, have been described. The most recognized subtype is the fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which is characterized by marked fibrous replacement of the thyroid parenchyma and microscopic changes typical of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in the remaining tissue.2 In contrast to Riedel’s thyroiditis, there is no extrathyroidal fibrosis in fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

In the last few years, there have been significant advances in our understanding of a novel condition known as IgG4-related disease. This disease process was initially recognized in relation to autoimmune pancreatitis in 2001.3, 4, 5 Since then, many other IgG4-related lesions similar to autoimmune pancreatitis have been reported all over the world, including retroperitoneal fibrosis,5 sclerosing cholangitis,6 sclerosing sialadenitis,7 tubulointerstitial nephritis,8 inflammatory pseudotumor,9, 10 and inflammatory aortic aneurysm.11 IgG4-related disease is characterized by elevated serum IgG4 levels, and in the clinical setting, by the alleviation of symptoms after steroid therapy. Furthermore, irrespective of the organs affected, the IgG4-related lesions also share similar pathologic features, including lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, fibrosis, obliterative phlebitis, and increased numbers of IgG4-positive plasma cells. These histological features have been utilized as morphological hallmarks of IgG4-related disease.3, 12

Recently, a high prevalence of hypothyroidism has been reported in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis.13 This finding led us to investigate the relationship between Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and IgG4-related disease. In 2009, our group first described a small subtype of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis with a substantial infiltrate of IgG4-positive plasma cells present in the inflamed thyroid tissue. This subtype shared similar histological features with IgG4-related disease in the other organs. Based on the immunohistochemical staining of IgG4 and IgG, it was proposed that Hashimoto’s thyroiditis can be divided into two subgroups, IgG4 thyroiditis and non-IgG4 thyroiditis. It was suggested that IgG4 thyroiditis might have a close relationship with IgG4-related disease.14 Similarities were also reported between IgG4 thyroiditis and fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Further clinical investigation demonstrated that IgG4 thyroiditis is associated with a lower female-to-male ratio, a more rapid progression, subclinical hypothyroidism, diffuse low sonographic echogenicity, and a higher level of circulating thyroid autoantibodies than the level found in non-IgG4 thyroiditis.15

Although IgG4 thyroiditis presents clinicopathological features that are quite distinct from those of typical Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, a systemic evaluation of the morphological features of this entity has not been performed. In this study of 105 patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, we examined the detailed histopathological characteristics of the IgG4 thyroiditis group and compared these findings with the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group. We focused on investigating the similarities and possible relationship between IgG4 thyroiditis and fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

Patients and methods

Case Selection

A total of 105 cases of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis between 1983 and 2010 were selected from the pathology files of Kuma Hospital (Kobe, Japan). Among these patients, 35 new cases (2007–2010) were added to the series of 70 cases (1983–2006), which have been reported in previous clinical analyses.15 There were 10 male and 95 female patients with an average age of 57 years (range: 23 to 80 years) involved in this study. The patients underwent total thyroidectomies for various reasons, including marked swelling (n=55), tracheal stenosis (tracheal compression by an enlarged thyroid gland) (n=19), pain and tenderness (n=4), nodular lesion (n=13), suspected malignant lymphoma (n=12), or suspected papillary thyroid carcinoma (n=2). The clinical data, including the presenting clinical, laboratory, and sonographic findings, medical history, treatment, and disease outcomes, were obtained from the referral forms submitted at the time of the operation and the patients’ medical records. The laboratory results indicated the presence of the anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody and the anti-thyroglobulin antibody. Ultrasonography of the neck was performed in all patients as previously described by Li et al.15 The follow-up period was calculated from the first and last visits to Kuma Hospital. The mean follow-up interval was 13 years (range 6 months to 40 years). The clinical diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis was based on the Guidelines of the Japanese Thyroid Society,15 and it was further confirmed by histological examination of the surgically resected specimens. The typical histological features of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis include a lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, a germinal center formation, follicular destruction, a Hurthle cell change, and variable degrees of fibrosis.16, 17 The incidental findings of focal (non-specific) lymphocytic thyroiditis in the tumor-bearing thyroid tissue were excluded from this study. This study was approved by the Kuma Hospital Bioethical Committee.

Histological Evaluation

The resected thyroid tissues were routinely fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (4-μm thick) from each patient were prepared for hematoxylin and eosin, Elastica van Gieson, Masson's trichrome, and immunohistochemical staining. Two pathologists, YL and KK, retrospectively reviewed >5 hematoxylin and eosin sections in each case. One sample from each representative block was immunohistochemically examined. We identified the presence or absence of the following histological features from the stained specimens: stromal fibrosis, lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, obliterative phlebitis, follicular size, follicular cell degeneration, lymphoid follicle formation, giant cell and/or histiocyte infiltration, and the presence of a solid cell nest and or squamous metaplasia. The following criteria were used to assess the degree of stromal fibrosis: ‘3+’ if more than half of the thyroid parenchyma had been replaced by fibrous tissue; ‘2+’ if one-third to half of the thyroid parenchyma had been replaced by fibrous tissue; ‘1+’ if less than one-third of the thyroid parenchyma had been replaced by fibrous tissue; and ‘−’ if the fibrosis was negligible. The specimens that were scored as 3+ and 2+ also met the diagnostic criteria for fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis specified in the report by Katz and Vickery.2 Additionally, the follicular size was defined as: micro-follicular (smaller than a normal follicle, diameter <100 μm), normal-follicular (diameter approximately 200–400 μm), and macro-follicular (larger than a normal follicle, diameter >500 μm). The degree of follicular cell degeneration was classified by the percentage of degenerated follicular epithelial cells observed under high-powered magnification as: severe (3+, >50%); moderate (2+, 33 to 50%); mild (1+, <33%); and ‘−’ (negligible degeneration). The degree of the lymphoid follicle formation was assessed using the prevalence of the lymphoid follicles in the thyroid stroma as follows: ‘3+’ (frequent formation); ‘2+’ (occasional formation); ‘1+’ (rare formation); and ‘−’ (negligible formation). The degree of giant cell/histiocytic infiltration was then rated as ‘3+’ (severe, >10/high-powered field), ‘2+’ (moderate, ≥5/high-powered field), ‘1+’ (mild, <5/high-powered field), and ‘−’ (negligible). Furthermore, as described in our previous report, the degree of lymphoplasmacytic infiltration was also described in this manner.14

Immunohistochemistry

The immunostaining was carried out using the EnVision immunohistochemical detection system (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primary antibodies were a mouse monoclonal antibody against human IgG4 (MC011, 1:500; Binding Site, Birmingham, UK) and a rabbit polyclonal antibody against human IgG (A0423, 1:8000; Dako Cytomation, Japan). Tonsil tissue served as a positive control.10 For the quantification of IgG4-positive or IgG-positive cells, the areas with the highest density of positive cells were evaluated. Five high-powered fields in each section were analyzed, and the average number of positive cells per high-powered field was calculated using Win ROOF version 5.8 image analysis software (Mitani, Tokyo, Japan). One high-powered field covered an area of 0.034 mm2 (AX80T microscope, × 10 eyepiece and × 40 lens; DP70 camera and DPController software; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The ratio of the IgG4-positive plasma cells to the IgG-positive plasma cells was also calculated in each case.

Statistical Analysis

Data are shown as the arithmetic mean±s.d. for continuous variable. Statistical analyses were performed using the unpaired t-test to compare the age and disease duration. Data with a skewed distribution, such as anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody and anti-thyroglobulin antibody fold changes, were summarized as geometric mean and 95% confidence interval, and the comparison between groups was performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test among the different groups. Any differences in gender, indications for thyroidectomy, thyroid functional status, and echogenicity between the various subgroups were determined by the χ2 test or the Fisher exact probability test. A probability of P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Sub-Classification of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis

On the basis of the immunostaining for IgG4 and IgG and the cutoff value proposed in our previous report (>20/high-powered field IgG4-positive plasma cells and a IgG4/IgG ratio >30%),14 the 105 patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis were sub-classified as having IgG4 thyroiditis (n=28) or non-IgG4 thyroiditis (n=77). There was no evidence of IgG4-related disease reported in the other organ systems of the 105 patients.

Clinical and Laboratory Findings

The clinical and laboratory findings of the patients of the two subgroups were compared, and the results are summarized in Table 1. The IgG4 thyroiditis group included 7 men and 21 women with a mean age of 52 years (range 23–77 years), whereas the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group consisted of 3 men and 74 women with a mean age of 59 years (range 34–80 years). The patients in the IgG4 thyroiditis group were significantly younger than those in the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group (P=0.0034). Although the female-to-male ratio is approximately 8–9:1 for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, the IgG4 thyroiditis group had a lower female-to-male ratio (P=0.0033). Additionally, patients in the IgG4 thyroiditis group had a significantly shorter disease duration of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (8±8 years) than those in the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group (15±10 years) before they underwent total thyroidectomies; however, there was no significant difference in the indications for thyroidectomy between the two groups (P=0.5035). In terms of routine laboratory examinations and the circulating thyroid autoantibody levels, both the anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody and anti-thyroglobulin antibody levels (geometric mean and 95% confidence interval: anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody, 176 (73–427) fold; anti-thyroglobulin antibody, 562 (178–1778) fold), were significantly higher in the IgG4 thyroiditis subgroup than in the non-IgG4 thyroiditis subgroup (geometric mean and 95% confidence interval: anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody, 85 (55–133) fold; anti-thyroglobulin antibody, 147 (72–303) fold) (P=0.0086; P=0.0168, respectively). The majority of patients involved in this study were treated with levothyroxine at a thyroid stimulating hormone-suppressive dose before surgery. With the thyroid hormone treatment, the patients demonstrated different levels of thyroid function, including subclinical hypothyroidism, euthyroidism, and subclinical hyperthyroidism. Their distribution significantly differed between the two groups (P=0.0041), and the IgG4 thyroiditis subtype was more strongly associated with subclinical hypothyroidism. Furthermore, the sonographic examinations revealed that the IgG4 thyroiditis group was significantly correlated with diffuse low echogenicity, whereas the non-IgG4 thyroiditis patients showed an association with diffuse coarse echogenicity (P=0.0002). In summary, the above results were consistent with our previous conclusion that the IgG4 thyroiditis is characterized by distinct clinical, laboratory, and sonographic features compared with its counterpart, non-IgG4 thyroiditis.15

Gross Findings

The surgical specimens of each thyroid revealed a clearly demarcated capsule that was non-adherent to the surrounding structures; therefore, the diagnosis of Riedel’s thyroiditis was reliably ruled out. The weight of the resected thyroid varied considerably, ranging from 13 to 425 g. In Japanese adults, the normal thyroid gland weighs about 17–19 g in males and 15–17 g in females.18 Of the 105 patients, only two (one case each from the IgG4 thyroiditis group and the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group) had thyroids of normal or decreased weight. The majority of the thyroid glands showed a diffuse symmetric enlargement without the presence of a dominant mass. The cut surfaces of the thyroid glands from the IgG4 thyroiditis patients showed a marked pale-white color with lobulations. This finding may signify increased fibrosis and lymphoid tissue (Figure 1a) in IgG4 thyroiditis and suggests a macroscopic similarity to fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. In the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group, the thyroid glands presented with varying degrees of mahogany-brown to tan-yellow color on the cut surfaces (Figure 1b). Although lobulations were also noted in the non-IgG4 thyroiditis patients, they were not as severe as those observed in the IgG4 thyroiditis group. No evidence of necrosis or calcification was identified in either of the groups.

Gross pathology of IgG4 thyroiditis and non-IgG4 thyroiditis. (a) IgG4 thyroiditis: the entire cut section had a pale-white color with lobulations, which indicated the replacement of the thyroid parenchyma with fibrous tissue. (b) Non-IgG4 thyroiditis: the cut section had a mahogany-brown color, which was also observed on the cut section of a normal thyroid.

Histological Findings

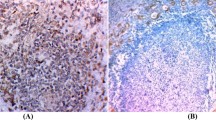

The IgG4-related lesions share many histological findings irrespective of the location.19 The general morphological hallmarks include an increased number of IgG4-positive plasma cells, extensive lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, stromal fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis. These features were compared between the IgG4 thyroiditis and non-IgG4 thyroiditis groups, and the data are summarized in Table 2. Immunohistochemically, the IgG4 thyroiditis group showed diffuse or nodular dense infiltration of the IgG4-positive plasma cells (54±31/high-powered field) with a high ratio of IgG4/IgG-positive plasma cells (52±18%) (Figures 2a and b). In contrast, in the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group, although many IgG-positive plasma cells were found in the stroma, only a few were IgG4-positive (8±7/high-powered field) (11±10%) (Figures 2c and d). Moreover, as we previously suggested, the IgG4 thyroiditis group (Figure 3a) showed a significantly higher grade of lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and stromal fibrosis than the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group (Figure 3b). As we suspected, the majority of the IgG4 thyroiditis cases could be classified as fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis as well, but these two entities do not completely overlap. In the IgG4 thyroiditis group, marked stromal fibrosis was observed in 24 cases (24/28, 86%), supporting the designation of these cases as fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. However, there were still four cases (4/28, 14%) that presented with only mild fibrosis. Even in the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group, there were 29 cases (29/77, 38%) with notable fibrosis that met the diagnostic criteria for fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. To further delineate the relationship between IgG4 thyroiditis and fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, an analysis of the pattern of fibrosis was conducted in this study. We formally proposed to classify the stromal fibrosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis into the three following patterns: interlobular fibrosis, interfollicular fibrosis, and scar fibrosis. Interlobular fibrosis was the most common type of sclerotic change noted in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. The term interlobular fibrosis was utilized to describe the condition in which fibrous tissue surrounds and extends between the individual lobules (a small group of follicles) and obliterates the usual loose stroma (Figure 4a). Interfollicular fibrosis was defined as increased fibrous tissue within the interfollicular space separating the individual thyroid follicles (Figure 4b). Occasionally, dense keloid-like fibrosis was also noted in the stroma of the thyroid glands, and this was referred to as scar fibrosis in this study (Figure 4c). The three patterns of stromal fibrosis in thyroid glands could occur in combination, but a predominant pattern was always present, that is, one of these patterns always composed more than half of the fibrous element. Among the cases that met the diagnostic criteria for fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in the IgG4 thyroiditis group, 23 cases (23/24, 96%) displayed predominant interfollicular fibrosis, and only one case presented a predominant interlobular pattern. Meanwhile, in the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group, 48 cases (48/77, 62%) revealed almost negligible to mild fibrosis. Among the remaining 29 cases that could be classified as fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, 19 cases (19/29, 66%) showed a predominant interlobular pattern and 10 cases (10/29, 34%) presented a predominant interfollicular pattern. Scar fibrosis was noted in two cases of IgG4 thyroiditis and in two cases of non-IgG4 thyroiditis. Based on the above results, one can speculate that IgG4 thyroiditis is more likely to be observed among the fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis with predominant interfollicular fibrosis. Obliterative phlebitis is a characteristic feature of IgG4-related disease. However, it was not identified in any of the 105 cases of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

Immunohistochemistry of IgG4 and IgG. In the IgG4 thyroiditis group, immunostaining revealed numerous IgG-positive plasma cells (a), many of which were IgG4-positive (b) (immunostaining, × 100). In the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group, although many IgG-positive plasma cells (c) were present in the stroma, only a small proportion of IgG4-positive plasma cells (d) were observed in a similar microscopic field (immunostaining, × 100).

Representative histopathological features of IgG4 thyroiditis and non-IgG4 thyroiditis. (a) IgG4 thyroiditis: diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, marked stromal fibrosis, and atrophy of the thyroid parenchyma (H&E, × 100). (b) Non-IgG4 thyroiditis: note the mild-to-moderate lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, lymphoid follicle formation, varying sizes of the thyroid follicles with dense colloid, and oxyphilic changes in the follicular epithelium (H&E, × 100).

Histopathological patterns of stromal fibrosis in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. (a) Interlobular fibrosis: the fibrous tissue is surrounded and extended between the individual lobules, and the usual loose stroma has been obliterated (H&E, × 100). (b) Interfollicular fibrosis: the small thyroid follicles have been separated by the deposition of fibrous tissue with lymphoplasmacytic infiltration in the interfollicular area (H&E, × 200). (c) Scar fibrosis: the large fibrous bands with low cellularity replaced the underlying thyroid follicle architecture (H&E, × 100).

The IgG4 thyroiditis group also revealed various thyroid-specific pathological features compared with IgG4-related disease in the other organs. The related data are summarized in Table 3. In the IgG4 thyroiditis group, many lymphocytes and plasma cells penetrated into and/or between the follicular epithelial cells, causing follicular basement membrane abnormalities and marked follicular cell degeneration (Figure 5a). The degenerated follicular epithelial cells had abundant pale-pink-colored cytoplasm and mild nuclear atypia. Additionally, the thyroid architecture was destroyed and replaced by fibrous tissue and the associated lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. The remaining thyroid parenchyma revealed islands of micro-follicles without or with only a small amount dense colloid (Figure 5b). In the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group, the degree of follicular cell degeneration was mild. The size of the thyroid follicles was significantly larger than those observed in IgG4 thyroiditis. A presence of lymphoid follicles with well-developed germinal centers is one of the diagnostic histological characteristics of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. This feature was frequently identified in both the IgG4 thyroiditis group and the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group. Generally, infiltration by multinucleated giant cells or histiocytes is recognized as a cytological feature that is characteristic of subacute thyroiditis. However, this histological feature can also be occasionally noted in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. In this study, we demonstrated that the IgG4 thyroiditis group presented with a higher frequency of severe giant cell/histiocyte infiltration (P=0.0002) in comparison with the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group. The histology of 19 of 28 cases of IgG4 thyroiditis (68%) revealed moderate-to-severe giant cell/histiocyte infiltration. These accumulated giant cells/histiocytes were noted in the fibrous stroma, where they were mixed with destroyed thyroid follicles, lymphocytes, and plasma cells (Figure 5c), or penetrating the follicle lumens (Figure 5d). In contrast, the histology of 55 cases of non-IgG4 thyroiditis (55/77, 71%) revealed almost negligible or mild giant cell/histiocyte infiltration. Solid cell nests or squamous metaplasia of the follicular epithelium may have also been observed in the thyroid gland (Figure 5e). This feature most likely reflects hyperplasia of the ultimobranchial body rests and is more commonly encountered in fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.20, 21 However, no significant difference was identified between IgG4 thyroiditis and non-IgG4 thyroiditis regarding this morphological feature. In brief, the IgG4 thyroiditis group revealed a distinct histological picture from the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group. All fibroinflammatory changes were limited by the thyroid capsule (Figure 5f).

Thyroid-specific histological features of IgG4 thyroiditis. (a) Severe lymphoplasmacytic infiltration consisting of lymphocytes and plasma cells was noted in the stroma surrounding the thyroid follicles among epithelial cells and occasionally extending into the follicle lumen (H&E, × 200). (b) Prominent atrophic thyroid follicles were lined by degenerated epithelium with a pale pink color and mild nuclear atypia, and contained a few dense colloids (H&E, × 200). (c) Many multinucleated giant cells were mixed with the destroyed thyroid follicles and fibro-inflammatory tissue (H&E, × 100). (d) Pronounced histiocytes penetrated into and between follicular epithelial cells (H&E, × 100). (e) Solid cell nests/squamous metaplasia: Solid cell nests/squamous metaplasia were occasionally noted in both the IgG4 thyroiditis and non-IgG4 thyroiditis groups (H&E, × 200). (f) Although lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and increased fibrosis replaced the normal thyroid tissue, these changes were limited within the thyroid capsule (H&E, × 40).

Discussion

IgG4-related disease is a novel clinicopathological disease entity that is accompanied by an elevated serum IgG4 concentration and is histologically characterized by an inflammatory sclerosing process that usually includes abundant IgG4-positive plasma cells. Recently, our group reported a unique subtype of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis showing indistinguishable histological features from IgG4-related disease. The lesion was termed as IgG4 thyroiditis. We speculated that this subgroup of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis may have a close relationship with IgG4-related disease.14 Moreover, in a recent clinical investigation, we demonstrated that IgG4 thyroiditis presents with distinct clinical, serological, and sonographic characteristics from non-IgG4 thyroiditis.15 The above findings were confirmed in this study, in which IgG4 thyroiditis was associated with a male predominance, a rapid progression, subclinical hypothyroidism, a higher level of circulating autoantibodies, and diffuse low echogenicity. Previous reports have stated that a higher prevalence of IgG4-related disease has been observed in elderly men. In contrast, our cases showed that the IgG4 thyroiditis group was significantly associated with a younger patient age at the time of the operation compared with the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group. The relatively shorter duration of disease before the thyroidectomy of the IgG4 thyroiditis group might contribute to this finding. Furthermore, despite the meticulous examination of all the clinical charts by two of the authors, from the 28 patients with IgG4 thyroiditis, we could not identify a case in which other organ systems developed IgG4-related disease during the follow-up period. This observation does not indicate that IgG4 thyroiditis is not a member of IgG4-related disease; even if many patients with IgG4-related disease have lesions in multiple organs, either synchronously or metachronously, other patients will still present with the involvement of a single organ.22 We speculate that IgG4 thyroiditis group of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is likely to occur as an organ-specific IgG4-related lesion.

In the past, the pathology of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis was considered to be uniform, but more recently, the histology has varied.16 Hence, several histological subtypes of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis have been identified. The most widely recognized subgroup is referred to as the fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which accounts for approximately 10% of the Hashimoto’s thyroiditis cases.23 Katz and Vickery2 defined this lesion in 1974 and proposed the following diagnostic criteria: (1) a marked fibrous replacement of more than one-third of the thyroid parenchyma and (2) changes typical of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in the remaining tissue. They also demonstrated that fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis reveals a series of clinical features that are quite distinct from those of typical Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, including a firm goiter (often presenting with a notable recent enlargement), frequent diagnostic confusion with a malignancy, a marked elevation in the tanned red cell titer and thyroglobulin, and thyroid function tests often indicating hypothyroidism. Based on these observations, Katz and Vickery suggested that fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis might represent a clinicopathological entity distinct from that of the typical form of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. In our previous publication, we reported a high histological similarity between IgG4 thyroiditis and fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and suggested that there may be substantial overlap between the two entities.14 It was once speculated that IgG4 thyroiditis and fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis represent the same disease process but are described with different terminology.24 However, in this study, we have demonstrated that these two entities are not the same. This observation is noteworthy for both clinicians and pathologists to avoid the overdiagnosis of all fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis as IgG4 thyroiditis. Since its description in the mid-1950s, there have been few reports focusing on the detailed fibrosis patterns of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.25 This has raised the question of whether the IgG4 thyroiditis group of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis has a special correlation with a unique pattern of fibrosis. This study evaluated the morphological features of stromal fibrosis in 105 Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients and demonstrated that IgG4 thyroiditis is significantly associated with a predominant interfollicular pattern of fibrosis. A predominant interlobular fibrosis is commonly seen in non-IgG4 thyroiditis. Based on the above findings, we suggest that the degree and pattern of fibrosis can be recognized as a useful clue for investigators to microscopically distinguish between the IgG4-related and non-IgG4-related subsets of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. It may also be valuable for pathologists to establish practical diagnostic criteria for IgG4-related Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in the future.

Although the IgG4 thyroiditis group of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis reveals certain histological features that are commonly observed in extrathyroidal IgG4-related disease, obliterative phlebitis, which is also one of the histological characteristics of IgG4-related disease reported in the other organs,26 has not been identified in any variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.27 The absence of obliterative phlebitis was confirmed in our 105 cases of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, including both IgG4 thyroiditis and non-IgG4 thyroiditis, which is consistent with the textbook descriptions of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.16 This is one of the most important observations reported in our series, and we believe that it does not conflict with our theory that IgG4 thyroiditis is one of the thyroid manifestations of IgG4-related disease. However, the IgG4 thyroiditis group also demonstrated thyroid-specific histological features, including the presence of small thyroid follicles, marked follicular cell degeneration, and increased giant cell/histiocyte infiltration, whereas the non-IgG4 thyroiditis patients presented with relatively mild aspects or complete absence of these histopathological characteristics. In the past, a strong correlation between the various degrees of the thyroid architecture destruction and the different types of echogenicity has been suggested.28, 29 Hayashi et al28 first proposed that the hypoechogenicity of the thyroid is a sign indicating severe follicular degeneration. In the current series, a similar conclusion has also been reached because of a more diffuse hypoechogenicity related to the severe degeneration and the lack of normal-sized thyroid follicles observed in the IgG4 thyroiditis group, whereas diffuse, coarse echogenicity was generally observed in the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group with less destruction.

When considering a diagnosis of IgG4-related Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, a clinical distinction must be made from Riedel’s thyroiditis. Riedel’s thyroiditis is a rare form of chronic thyroiditis that is characterized by an inflammatory proliferative fibrosing process.27, 30, 31 As a result of the histological similarity, confusion has been noted in the literature regarding Riedel’s thyroiditis and fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.23 Most recently, an association between Riedel’s thyroiditis and IgG4-related disease has been described by Dahlgren et al.32 They demonstrated excessive numbers of the IgG4-positive plasma cells in Riedel’s thyroiditis samples. This observation would seem to further blur the distinction between the IgG4-related Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Riedel’s thyroiditis. Based on the previous literature and this study concerning IgG4-related Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, we suggest that there are at least two characteristics that can help distinguish IgG4-related Hashimoto’s thyroiditis from Riedel’s thyroiditis. First, the absence of extensive fibrosis beyond the thyroid capsules is still the most reliable evidence to confirm a diagnosis of IgG4-related Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Second, Riedel’s thyroiditis has generally been considered to be associated with various forms of systemic fibrosis. Dahlgren et al32 reported one patient with IgG4-related disease who also presented with involvement of the lacrimal gland, pulmonary, and biliary tracts as well as Riedel’s thyroiditis. However, in the current series, there were no cases of IgG4-related Hashimoto’s thyroiditis showing systemic or non-thyroid IgG4-related lesions. Although IgG4-related Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Riedel’s thyroiditis are two distinct entities, they share the pathophysiology of IgG4-related disease. Therefore, there may be a potential association between the two that needs further investigation.

Additional differentiation must be made with subacute thyroiditis, because giant cell/histiocytic reactions were found in some of our series. Subacute thyroiditis is also referred as giant cell granulomatous thyroiditis or De Quervain thyroiditis.17 Disruption of thyroid follicles associated with multinucleated giant cells and histiocytic reaction are diagnostic characteristics for subacute thyroiditis, when they were examined in early hyperthyroid phase. There are two different points to distinguish IgG4 thyroiditis and subacute thyroiditis histopathologically. First, subacute thyroiditis usually occurs asymmetrically while IgG4 thyroiditis occurs diffusely in the entire gland. Second, the giant cells and histiocytic inflammation in subacute thyroiditis may be associated with acute inflammation, such as micro-abscess, but acute inflammation was not found in our series.

Although this is the first study presenting a morphological comparison between the IgG4-related and non-IgG4-related groups of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, there are several limitations that should be emphasized. We only selected patients who received surgical treatment. Therefore, the patient population may disproportionately represent those with severe manifestations, and the milder cases may have been overlooked. In the clinical setting, it is often difficult to distinguish between the lack of documentation and the actual absence of a particular symptom. Therefore, the absence of extrathyroidal IgG4-related disease cannot be totally confirmed. Furthermore, serum IgG4 levels are useful in the identification of IgG4-related disease. Although we demonstrated in our previous publication that serum IgG4 levels were significantly elevated in the IgG4 thyroiditis group of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, the serum samples were not available to measure the IgG4 concentrations to confirm the previous serological observation.

In conclusion, IgG4 thyroiditis patients revealed distinct histopathological features from those of the non-IgG4 thyroiditis group. Further investigations are required to determine the potential immunopathogenetic mechanism underlying this unique subtype.

References

Hashimoto H . Zur Kenntnis der lymphomatösen Veränderung der Schilddrüse (Struma lymphomatosa). Arch Klin Chir 1912;97:219–248.

Katz SM, Vickery Jr AL . The fibrous variant of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Hum Pathol 1974;5:161–170.

Hamano H, Kawa S, Horiuchi A, et al. High serum IgG4 concentrations in patients with sclerosing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 2001;344:732–738.

Kamisawa T, Funata N, Hayashi Y, et al. A new clinicopathological entity of IgG4-related autoimmune disease. J Gastroenterol 2003;38:982–984.

Hamano H, Kawa S, Ochi Y, et al. Hydronephrosis associated with retroperitoneal fibrosis and sclerosing pancreatitis. Lancet 2002;359:1403–1404.

Zen Y, Harada K, Sasaki M, et al. IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis with and without hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor, and sclerosing pancreatitis-associated sclerosing cholangitis: do they belong to a spectrum of sclerosing pancreatitis? Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:1193–1203.

Kitagawa S, Zen Y, Harada K, et al. Abundant IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration characterizes chronic sclerosing sialadenitis (Kuttner’s tumor). Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:783–791.

Takeda S, Haratake J, Kasai T, et al. IgG4-associated idiopathic tubulointerstitial nephritis complicating autoimmune pancreatitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004;19:474–476.

Zen Y, Kitagawa S, Minato H, et al. IgG4-positive plasma cells in inflammatory pseudotumor (plasma cell granuloma) of the lung. Hum Pathol 2005;36:710–717.

Zen Y, Fujii T, Sato Y, et al. Pathological classification of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor with respect to IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol 2007;20:884–894.

Kasashima S, Zen Y, Kawashima A, et al. Inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysm: close relationship to IgG4-related periaortitis. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:197–204.

Kamisawa T, Okamoto A . IgG4-related sclerosing disease. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:3948–3955.

Komatsu K, Hamano H, Ochi Y, et al. High prevalence of hypothyroidism in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci 2005;50:1052–1057.

Li Y, Bai Y, Liu Z, et al. Immunohistochemistry of IgG4 can help subclassify Hashimoto’s autoimmune thyroiditis. Pathol Int 2009;59:636–641.

Li Y, Nishihara E, Hirokawa M, et al. Distinct clinical, serological, and sonographic characteristics of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis based with and without IgG4-positive plasma cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:1309–1317.

Lloyd RV, Douglas BR, WF Y, (eds). Endocrine Diseases. The American Registry of Pathology: Washington, DC, 2002, 91–149 pp.

Pearce EN, Farwell AP, Braverman LE . Thyroiditis. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2646–2655.

Tanaka G, Nakahara Y, Nakazima Y . [Japanese reference man 1988-IV. Studies on the weight and size of internal organs of Normal Japanese]. Nihon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi 1989;49:344–364.

Zen Y, Nakanuma Y . IgG4-related disease: a cross-sectional study of 114 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:1812–1819.

Ozaki T, Nagashima K, Kusakabe T, et al. Development of thyroid gland and ultimobranchial body cyst is independent of p63. Lab Invest 2010;91:138–146.

Kakudo K, Kitamura H, Miyauchi A, et al. Squamous metaplasia of human thyroid gland—an electron microscopic study of solid cell nest. Med J Osaka Univ 1977;28:33–38.

Umehara H, Okazaki K, Masaki Y, et al. A novel clinical entity, IgG4-related disease (IgG4RD): general concept and details. Mod Rheumatol 2012;22:1–14.

LiVolsi VA . The pathology of autoimmune thyroid disease: a review. Thyroid 1994;4:333–339.

Khosroshahi A, Stone JH . A clinical overview of IgG4-related systemic disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2011;23:57–66.

Hazard JB . Thyroiditis: a review II. Am J Clin Pathol 1955;23:399–426.

Cheuk W, Chan JK . IgG4-related sclerosing disease: a critical appraisal of an evolving clinicopathologic entity. Adv Anat Pathol 2010;17:303–332.

Papi G, LiVolsi VA . Current concepts on Riedel thyroiditis. Am J Clin Pathol 2004;121 (Suppl):S50–S63.

Hayashi N, Tamaki N, Konishi J, et al. Sonography of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. J Clin Ultrasound 1986;14:123–126.

Sostre S, Reyes MM . Sonographic diagnosis and grading of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. J Endocrinol Invest 1991;14:115–121.

Hay ID . Thyroiditis: a clinical update. Mayo Clin Proc 1985;60:836–843.

Hennessey JV . Clinical review: Riedel’s thyroiditis: a clinical review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:3031–3041.

Dahlgren M, Khosroshahi A, Nielsen GP, et al. Riedel’s thyroiditis and multifocal fibrosclerosis are part of the IgG4-related systemic disease spectrum. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:1312–1318.

Acknowledgements

Portions of this work were presented in the poster form at the 100th Annual Meeting of the USCAP, San Antonio, TX, USA, 26 February–4 March 2011. An ADASP/USCAP Surgical Pathology Award was given to Dr Yaqiong Li.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Zhou, G., Ozaki, T. et al. Distinct histopathological features of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis with respect to IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol 25, 1086–1097 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.68

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.68

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The characteristics and clinical significance of elevated serum IgG4/IgG levels in patients with Graves’ disease

Endocrine (2022)

-

Assessment of thyroid gland elasticity with shear-wave elastography in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients

Journal of Ultrasound (2020)

-

Malattie autoimmuni della tiroide e IgG4

L'Endocrinologo (2020)

-

Case report: IgG4-related mass-forming thyroiditis accompanied by regional lymphadenopathy

Diagnostic Pathology (2018)

-

PD-L1 and PD-1 expression are correlated with distinctive clinicopathological features in papillary thyroid carcinoma

Diagnostic Pathology (2017)