Abstract

Clinical staging is a critical step in the management of testicular germ cell tumors. Up to one-third of nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis present with metastatic disease (clinical stages II and III). We investigated the predictors of metastatic disease at presentation in a cohort of 148 consecutive nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis, over a 10-year period. The following clinical and pathologic features were evaluated: age, tumor size, dominant tumor histology, coagulative necrosis, vascular invasion, rete testis invasion and tumor extension into tunica vaginalis, hilar soft tissue, epididymis, or spermatic cord. Studied parameters were correlated with the clinical stage at presentation. Of the 148 patients with nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis, 94 (63%) were clinical stage I, 26 (18%) were stage II, and 28 (19%) were stage III at presentation. Mean patient age was 31 years (range, 17–83). Mean tumor size was 4.1 cm (range, 0.6–19). On univariate analysis, the following parameters showed statistically significant association with the advanced clinical stage at presentation: vascular invasion (P<0.001), rete testis invasion (P<0.001), hilar soft tissue invasion (P<0.001), epididymis invasion (P=0.005), spermatic cord invasion (P=0.005), and coagulative necrosis (P=0.062). On multivariate analysis, only vascular invasion (P=0.011) and invasion into the rete testis and the hilar soft tissues (P=0.007 and P=0.017, respectively) demonstrated significant association with advanced clinical stage at presentation. We conclude that in addition to vascular invasion, tumor invasion into the hilum (rete testis or hilar soft tissue) is also strongly associated with metastatic disease at presentation and should be part of the routine pathology reporting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Testicular cancer is the most common solid tumor in men between the age of 15–35 years and it represents one of the most curable malignant solid tumors. The current focus of testicular cancer management is to reduce the treatment-related morbidity without jeopardizing the excellent clinical outcome. Germ cell tumors are comprised of two main histological subtypes: pure seminomas and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors, which may show a variety of histologic patterns, including combinations of seminoma and nonseminomatous germ cell tumor components. Nonseminomatous germ cell tumors represent 35–55% of all testicular germ cell tumors and approximately one-third of these patients present with clinically detectable metastatic disease (clinical stage II, with positive retroperitoneal nodes or clinical stage III, with distant metastatic disease).1 The predictors of metastatic disease are essential in customizing the clinical management for individual patients with nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Pathologic examination of radical orchiectomy specimens determines the pathological staging, which guides clinical management in germ cell tumors and is critical for the assessment of the local tumor spread. Vascular invasion and dominant embryonal carcinoma have been previously identified as histologic predictors for relapse, which led to the introduction of risk-adapted treatments in clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors.2, 3, 4

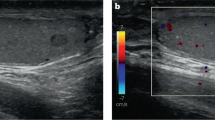

Although testicular hilum has been previously identified as the predominant pathway of extratesticular extension in testicular germ cell tumors, its significance as a predictor of metastatic disease has not been well studied.5, 6 Testicular hilum is composed of rete testis and extratesticular connective tissue, most commonly referred to as hilar soft tissue (Figure 1). Rete testis is a network of channels in the testicular hilum, which receives the luminal contents of the seminiferous tubules. Testicular hilum has been defined as a site at which rete testis emerges from the testis, including the adjacent 0.5 cm diameter of surrounding tissue.6 Rete testis invasion has been found to correlate with higher risk of relapse in stage I seminomas and it was also shown to correlate with clinical metastasis at the time of presentation.7, 8

To our knowledge, there are only limited data on the prognostic value of rete testis invasion in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors.3, 9, 10 Moreover, the significance of hilar soft tissue invasion in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors has not been previously studied. Therefore, we performed a comprehensive evaluation of the histopathologic variables in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors, aiming to investigate their prognostic significance for the clinical metastatic disease at the time of presentation, with an emphasis on tumor invasion into the hilum.

Materials and methods

Clinical and Pathologic Data

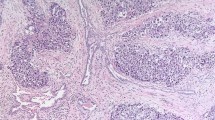

A total of 382 radical orchiectomies for malignant germ cell tumors were performed in our institution between October 1999 and June 2009. After excluding pure seminomas, we identified 152 (40%) nonseminomatous germ cell tumors with pure and mixed histology. The final study cohort included 148 consecutive cases of nonseminomatous germ cell tumor and the clinical stage was available for all 148 patients (clinical data were not available in four cases, which were excluded). All slides and pathology reports were reviewed by one pathologist without the knowledge of the clinical stage. The following gross and microscopic parameters were recorded: tumor size, lymphovascular invasion, rete testis invasion, and tumor extension beyond tunica albuginea (into tunica vaginalis, hilar soft tissues, epididymis, or spermatic cord). The dominant tumor histology (≥50% of the tumor) was also recorded; only 6 (4%) cases had dominant tumor histology <50% (range, 30–45%). Regarding the assessment of the tumor invasion into the hilar structures, rete testis invasion was defined as the presence of tumor cells in between the rete testis ducts. We also documented pagetoid tumor spread into the rete testis when involvement was exclusively pagetoid (in situ), which included individual or groups of cells, morphologically identical to intratubular germ cell neoplasia, present below or between the epithelial cells of rete testis and above the basement membrane (Figure 2).11 Hilar soft tissue invasion was defined as direct tumor extension into the extratesticular hilar connective tissues, beyond the rete testis (Figure 3). Pathologic staging was performed using the current American Joint Committee for Cancer (AJCC/TNM) staging system.12

Clinical data for metastatic disease at the time of presentation were collected from the patient medical records. Clinical stage was determined based on the chest X-ray and the CT of the pelvis and abdomen. Patients with clinical stage I disease had no clinical, radiological, or biochemical evidence of nodal or distant metastatic disease. In four (2.7%) patients, serum tumor markers were elevated during the post-orchiectomy period in the absence of clinically documented metastatic disease on routine imaging. These patients were categorized as stage IS according to the stage grouping classification and were clinically managed as stage II disease. Patients with clinical stage II disease demonstrated tumor spread into the retroperitoneal nodes and patients with clinical stage III had distant metastatic spread.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as medians for continuous variables with skewed distribution, and as frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. Medians were compared between the clinical stage I and the clinical stage II or III using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. For categorical variables, proportions were compared between the groups using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis were performed to explore potential risk factors for the presence of clinical metastases (ie, clinical stage II or III). The final multivariate logistic regression model was determined by conducting a backward stepwise model selection using Akaike’s information criterion based on full model including all the potential risk factors. The odds ratio and its associated 95% confidence interval were calculated when any statistically significant associations were found. All statistical tests were two-sided, and reported P-values were considered significant if <0.05. All analyses were performed using STATA 10 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Clinical Findings

At the time of the initial presentation, 94 (63%) patients were stage I and 54 (37%) patients had metastatic disease. Of these, 26 (18%) were stage II and 28 (19%) were stage III. Mean patient age was 31 years (range, 17–83 years).

Pathologic Findings

Mean tumor size was 4.1 cm (range, 0.6–19 cm). More than one germ cell component (mixed histology) was seen in 116 (78%) tumors and pure histology was identified in 32 (22%) patients. The most commonly identified tumor component was embryonal carcinoma, followed by teratoma, and yolk sac tumor in both mixed and pure nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (Table 1).

Of the 148 patients, vascular invasion was found in 61 (41%) cases (Figure 4). Status of rete testis was documented in 138 patients. Rete testis invasion was seen in 72/138 (52%) tumors. An additional 23/138 (17%) patients demonstrated rete testis involvement only by pagetoid (in situ) spread. Rete testis was negative for tumor invasion in 43 (31%) cases. In 10 (7%) cases, rete testis status could not be determined in the submitted sections; in 6 of these, the hilum was distorted and completely replaced by a tumor of large size (>10 cm) and in four cases, rete testis was not sampled. Invasion into hilar soft tissue was found in 42 (28%) tumors. Tumor invaded into the epididymis in 12 (8%) patients. Necrosis was a common finding and it was found in 113 (76%) cases. Invasion of tunica vaginalis was not identified in any patients. Spermatic cord involvement was reported in 12 (8%) patients. However on slide review, we were not able to confirm tumor invasion into the spermatic cord in four patients. These cases in which invasion to the base of the spermatic cord was suspected, but was not unequivocally present were not considered as pT3 in our analysis. We identified pT1 stage in 92 (62%) patients, 48 (32%) were pT2, and 8 (5%) were stage pT3 and pT4.

The histopathologic findings in patients with and without clinical metastasis at the time of initial presentation are compared in Table 2. On univariate analysis, vascular invasion, rete testis invasion and tumor extension into hilar soft tissues, epididymis and spermatic cord were significantly more common in patients showing metastastatic disease at the time of presentation (Table 3). On univariate analysis, the following variables: age, tumor size, and dominant embryonal carcinoma histology and rete testis involvement with pagetoid spread were not significantly associated with the presence of metastatic disease at presentation.

The final multivariate logistic regression model was determined by conducting a backward stepwise model, which was based on a full model. Full model included all the potential risk factors represented in the univariate analysis. The results of the multivariate analysis are demonstrated in two final separate models, which showed comparable values (Table 4). We analyzed the data on rete testis invasion and hilar soft tissue invasion separately because these two variables are interrelated due to their close anatomic proximity. Both parameters were independently associated with the presence of metastatic disease at the time of initial presentation. In both models, the presence of the vascular invasion remained a strong independent predictor for metastasis at presentation.

Discussion

In this study, we identified strong correlation between the clinically determined metastatic disease and the presence of tumor invasion into rete testis and hilar soft tissues in patients with nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. We also confirmed that vascular invasion is a significant risk factor for metastasis in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors, which is well documented previously.2, 3, 4, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

Clinical stage is the most critical step in the management of patients diagnosed with nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. A current challenge is the appropriate management of clinical stage I disease because of the concerns related to the adverse effects of the chemotherapy treatment. The goal is to select patients with clinical stage I disease who are at higher risk for relapse and will likely benefit from aggressive therapy. Therefore, determining reliable prognostic risk factors of occult metastases remain crucial. Surveillance only approach after the initial orchiectomy avoids over treatment, that is, unnecessary retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, in ∼70% of patients who are cured by orchiectomy alone.4 However, up to one-third of the patients who are managed by surveillance do relapse because of subclinical/occult metastasis at presentation or because of tumor progression. Histopathologic predictors of occult metastatic disease in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors have been previously studied in clinical stage I patients.20 The studies, however, differ according to the treatment approach used. Metastatic disease either was defined by relapse rates in patients managed initially by surveillance,9, 10, 13, 15, 21 or was determined by the presence of metastatic disease found on retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in patients who underwent surgical staging.2, 3, 4, 17, 19 Reported relapse rates of surveillance studies (27–30%)21 are virtually identical to the relapse rates observed in surgical studies.2, 4, 19 Most studies done on clinical stage I patients showed that embryonal carcinoma and vascular invasion in the primary tumor were reliable prognosticators in identifying patients for low or high risk for retroperitoneal metastasis,2 which is used in some centers for optimizing individual patient treatment. In low-risk patients, surveillance and treatment only after relapse is preferred. There is less agreement on the best treatment strategy for high-risk patients,22 because even by stratifying patients according to risk, 30–50% of patients are over treated by adjuvant therapy. Therefore, our objective was to investigate whether we can further improve patient selection in the high-risk group using detailed histopathologic analysis with emphasis on the tumor invasion into the testis hilum.

We identified rete testis invasion in 52% of the study group, which was significantly higher in patients who presented with metastastatic disease at the time of diagnosis (stage I: 40% vs stage II and III: 74%). The presence of rete testis invasion in stage I seminoma patients has been previously found to be an independent risk factor for relapse, in addition to tumor size.8 However, most of the previous studies on histologic prognosticators in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors lacked complete data on rete invasion or this issue was not addressed at all.2, 4, 17, 18, 19 Some previous studies focused only on patients with clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors.3, 9, 10 These early studies had either limited data on rete testis invasion3 or correlated rete testis invasion with higher risk of relapse only on univariate analysis,10 but not on multivariate analysis.9 Two early studies performed in the 1980s also correlated primary tumor histology with metastastatic disease at presentation.17, 18 In one, Moriyama et al studied a smaller cohort of 45 patients with nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of all stages and showed that vascular invasion increased the metastatic potential, but they did not investigate the invasion into rete testis and hilar soft tissue as possible prognosticators. In the second study, Rodriguez et al17 also found that invasion of rete testis, epididymis, and or/lower spermatic cord was associated with metastatic disease, but the significance of the invasion into these structures was less compelling due to missing data in 45% of the study group. Vascular invasion was also significantly more common in patients with metastatic disease in their study. None of the previous studies specifically addressed the pattern of rete testis involvement (pagetoid vs direct invasion). The pattern of rete testis involvement is important, because we identified pagetoid tumor spread as an exclusive pattern of rete testis involvement in 17% of the cases. We found that pagetoid tumor spread into rete testis was not associated with advanced clinical stage at presentation.

The prognostic significance of tumor extension into hilar soft tissues in germ cell tumors was not addressed in any previous study. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to address the prognostic significance of this pattern of local spread in germ cell tumors. We identified that tumor extension into the hilar soft tissues was present more often in patients with advanced clinical stage (stages II and III (48%) vs stage I (17%)) and remained a significant prognosticator in multivariate analysis. Dry et al6 reported in 1999 that testicular hilum represents the most common site of extratesticular extension in germ cell tumors and this was the first study to demonstrate that extratesticular extension of germ cell tumors preferentially occurs in the hilum. We previously confirmed this observation in a cohort of 289 patients and we showed that hilar soft tissue invasion was present in all cases with extratesticular extension.5 Hilar soft tissue invasion also correlated with adverse histologic findings, such as vascular invasion and rete testis invasion.5 Previous studies on germ cell tumors aiming to correlate tumor histology and outcome uniformly lacked data on hilar soft tissue invasion. This is possibly due to the fact that hilar invasion is not included in the current American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging12 and was only recently incorporated in the College of American Pathologists (CAP) reporting recommendations for testicular germ cell tumors.23 The results of this study also highlight the importance of the anatomic proximity of the hilar structures and emphasize the important interrelation of the invasion into rete testis and hilar soft tissues. Direct invasion into rete testis likely precedes hilar soft tissue involvement and represents an initial phase of tumor spread into the hilum. This is supported by our finding that tumor invasion into the hilar soft tissue was accompanied by rete testis invasion in 91% (38/42) of cases, while only 53% (38/72) of cases with rete testis invasion demonstrated hilar soft tissue invasion. We could not identify concurrent rete testis invasion only in four cases with hilar soft tissue invasion. In two, rete testis was significantly distorted and obscured by the large tumor size, in one, the section of rete testis did not reveal invasion, and in one case, rete testis was not sampled for histology. Therefore, rete testis and hilar soft tissue invasion, which are likely strongly interrelated, were analyzed separately in two multivariate models. Not surprisingly, both parameters were independently associated with advanced clinical stage with comparable odds ratios and P-values.

We also confirmed the prognostic significance of the vascular invasion in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors which was identified previously.2, 3, 4, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Since the initial data presented in the early 1980s by Peckham et al24 in patients with stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors managed by surveillance, the presence of vascular invasion and predominant embryonal carcinoma component have been considered significant risk factors for retroperitoneal and visceral metastasis.17, 25 Subsequent studies confirmed the importance of the vascular invasion as an independent predictor for relapse in clinical stage I patients.2, 9, 10, 17, 18, 25

In contrast to most of the previous studies, we did not find dominant embryonal carcinoma histology to be associated with clinically metastatic disease. Our study evaluated patients of all clinical stages in contrast to most previous studies which included only clinical stage I patients. Therefore, embryonal carcinoma histology may not play an important role in the pathogenesis of clinically detectable metastatic disease, which was the primary focus of this study. Similar to our study, Rodriguez et al17 also failed to show a significant association with the dominant histologic subtype and metastatic disease at presentation. Another possible explanation is the different cutoff points used for the embryonal carcinoma component by different studies (we used 50% cutoff).

The results of this study underscore the significance of the evaluation of the local tumor spread into the hilar structures, which requires special attention during routine gross and histologic examination of orchiectomy specimens. Currently, in order to document the possible invasion, pathologists sample the tumor in relation to tunica vaginalis, because this is a parameter identified in the current TNM staging system for testicular germ cell tumors. This approach targets the sampling at the tumor periphery rather than the hilum, where extratesticular tumor extension most likely occurs. In fact, none of the cases in our study showed involvement of tunica vaginalis and, in our opinion, this rare finding lacks well-documented prognostic value and should no longer be used for pathologic staging of germ cell tumors.

Not surprisingly, most of the previous studies that promoted risk stratification for the management of nonseminomatous germ cell tumors lacked information on the tumor invasion into the hilum.20 Documentation of status of tumor invasion into testicular hilum, as part of the routine testicular cancer synoptic reporting, will ensure more consistent sampling of this region and will allow collection of data to further investigate its value for risk stratification. We also propose that the pattern of rete testis involvement be clearly stated (in situ/pagetoid vs direct invasion) because of the lack of prognostic significance for exclusive pagetoid involvement found in this study.

The study limitations include its retrospective nature and the determination of the clinical stage by imaging and serum markers. A subgroup of clinical stage I patients in our study group may have had an occult (or subclinical) metastatic disease at presentation, because clinical staging may not be as accurate in detecting of small volume retroperitoneal metastasis (<10 mm).4 Another limitation may be an inconsistent gross sampling and reporting on the status of the hilum, particularly for the earlier cases in this study. Rete and hilar region invasion were only recently incorporated in the CAP checklist reporting, although they are still not part of the current TNM staging system. This was accounted for in this study by slide review with specific reassessment of these parameters; however, possible undersampling of the hilar region could not be excluded in a limited number of cases. Hilar soft tissue and rete invasion, including the pattern of rete involvement have been part of our germ cell tumors synoptic report since 2006, which prompted the pathologists in our institution to routinely sample and evaluate the testis hilum grossly and microscopically. The study does not address the crucial question in testicular cancer which is to find parameters that predict relapse in clinical stage I patients with nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Our results, however, provide a valid rationale to assess these histologic features in a cohort of clinical stage I patients who were either managed by retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy or were followed by surveillance.

In conclusion, this is the first study that investigated hilar soft tissue invasion as a possible prognosticator in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. We identified robust association between hilar tumor invasion and adverse clinical outcome, that is, advanced clinical stage at presentation. Therefore, we emphasize the importance of evaluating the testicular hilum, which appears to be the main venue for extratesticular extension in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Tumor extension into the hilar soft tissues is almost always preceded by tumor invasion into the rete testis. Thus, the status of rete testis and the hilar soft tissue invasion should be part of routine pathology reporting for germ cell tumors, which requires adequate sampling of the testicular hilum at the time of grossing.

References

Sonneveld DJ, Hoekstra HJ, Van Der Graaf WT et al. The changing distribution of stage in nonseminomatous testicular germ cell tumours, from 1977 to 1996. BJU Int 1999;84:68–74.

Heidenreich A, Sesterhenn IA, Mostofi FK et al. Prognostic risk factors that identify patients with clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors at low risk and high risk for metastasis. Cancer 1998;83:1002–1011.

Fung CY, Kalish LA, Brodsky GL et al. Stage I nonseminomatous germ cell testicular tumor: prediction of metastatic potential by primary histopathology. J Clin Oncol 1988;6:1467–1473.

Albers P, Siener R, Kliesch S et al. Risk factors for relapse in clinical stage I nonseminomatous testicular germ cell tumors: results of the German Testicular Cancer Study Group Trial. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1505–1512.

Yilmaz A, Trpkov K, Cheng T . Extratesticular extension in germ cell tumors. Virchows Arch 2008; (Suppl) 1:1.

Dry SM, Renshaw AA . Extratesticular extension of germ cell tumors preferentially occurs at the hilum. Am J Clin Pathol 1999;111:534–538.

Valdevenito JP, Gallegos I, Fernandez C et al. Correlation between primary tumor pathologic features and presence of clinical metastasis at diagnosis of testicular seminoma. Urology 2007;70:777–780.

Warde P, Gospodarowicz MK, Banerjee D et al. Prognostic factors for relapse in stage I testicular seminoma treated with surveillance. J Urol 1997;157:1705–1709 discussion 9-10.

Hoskin P, Dilly S, Easton D et al. Prognostic factors in stage I non-seminomatous germ-cell testicular tumors managed by orchiectomy and surveillance: implications for adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1986;4:1031–1036.

Pizzocaro G, Zanoni F, Salvioni R et al. Difficulties of a surveillance study omitting retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy in clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis. J Urol 1987;138:1393–1396.

Perry A, Wiley EL, Albores-Saavedra J . Pagetoid spread of intratubular germ cell neoplasia into rete testis: a morphologic and histochemical study of 100 orchiectomy specimens with invasive germ cell tumors. Hum Pathol 1994;25:235–239.

Sobin L, Gospodarowicz M, Wittekind C . UICC TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors 7th edn. Wiley-Liss: New York, NY, 2009.

Nicolai N, Pizzocaro G . A surveillance study of clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis: 10-year followup. J Urol 1995;154:1045–1049.

Alexandre J, Fizazi K, Mahe C et al. Stage I non-seminomatous germ-cell tumours of the testis: identification of a subgroup of patients with a very low risk of relapse. Eur J Cancer 2001;37:576–582.

Colls BM, Harvey VJ, Skelton L et al. Late results of surveillance of clinical stage I nonseminoma germ cell testicular tumours: 17 years’ experience in a national study in New Zealand. BJU Int 1999;83:76–82.

Dunphy CH, Ayala AG, Swanson DA et al. Clinical stage I nonseminomatous and mixed germ cell tumors of the testis. A clinicopathologic study of 93 patients on a surveillance protocol after orchiectomy alone. Cancer 1988;62:1202–1206.

Rodriguez PN, Hafez GR, Messing EM . Nonseminomatous germ cell tumor of the testicle: does extensive staging of the primary tumor predict the likelihood of metastatic disease? J Urol 1986;136:604–608.

Moriyama N, Daly JJ, Keating MA et al. Vascular invasion as a prognosticator of metastatic disease in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis. Importance in ‘surveillance only’ protocols. Cancer 1985;56:2492–2498.

Nicolai N, Miceli R, Artusi R et al. A simple model for predicting nodal metastasis in patients with clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell testicular tumors undergoing retroperitoneal lymph node dissection only. J Urol 2004;171:172–176.

Vergouwe Y, Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJ et al. Predictors of occult metastasis in clinical stage I nonseminoma: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:4092–4099.

Read G, Stenning SP, Cullen MH et al. Medical Research Council prospective study of surveillance for stage I testicular teratoma. Medical Research Council Testicular Tumors Working Party. J Clin Oncol 1992;10:1762–1768.

Horwich A, Shipley J, Huddart R . Testicular germ-cell cancer. Lancet 2006;367:754–765.

Tickoo SK, Reuter VE, Amin MB et al. Protocol for the Examination of Specimens from Patients with Malignant Germ Cell and Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors of the Testishttp://www.cap.org/apps/cap.portal 2011.

Peckham MJ, Barrett A, Husband JE et al. Orchidectomy alone in testicular stage I non-seminomatous germ-cell tumours. Lancet 1982;2:678–680.

Hoeltl W, Kosak D, Pont J et al. Testicular cancer: prognostic implications of vascular invasion. J Urol 1987;137:683–685.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yilmaz, A., Cheng, T., Zhang, J. et al. Testicular hilum and vascular invasion predict advanced clinical stage in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Mod Pathol 26, 579–586 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.189

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.189

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Total embedding of spermatic cord and hilar soft tissue in orchiectomy for seminoma: does the extensive sampling improve pathologic risk factors?

Virchows Archiv (2022)

-

Overexpression of melanoma-associated antigen A2 has a clinical significance in embryonal carcinoma and is associated with tumor progression

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2022)

-

Hodentumoren aus klinischer Sicht

Die Pathologie (2022)

-

Testicular Germ-Cell Tumors with Spermatic Cord Involvement: A Retrospective International Multi-Institutional Experience

Modern Pathology (2022)

-

Pathological predictors of metastatic disease in testicular non-seminomatous germ cell tumors: which tumor-node-metastasis staging system?

Modern Pathology (2021)