Abstract

The objective of this study is to measure interobserver variability in the classification of laryngeal mucosal premalignant lesions by reassessing the histopathology of previously diagnosed cases and to determine the possible therapeutic consequences of disagreement among observers. Histopathological assessment of 110 laryngeal mucosal premalignant lesions was done by three pathologists. Each slide had to be classified according to the World Health Organization, Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and the Ljubljana Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions systems. After the independent assessment, a joint meeting took place. To assess the relation between histopathological grading and subsequent clinical management, we created a two- and a three-grade system besides one comprising all options. For all analyses, the SAS/STAT statistical software was used. The highest unweighted κ-values concerning the all-options system are observed for the Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia classification (0.28, 95% confidence interval 0.23–0.33), followed by the World Health Organization and Ljubljana classifications. For the two-grade system the Ljubljana classification shows the highest unweighted κ-values (0.50, 95%, 0.39–0.61), followed by the World Health Organization and Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia classifications. For the three-grade system, the unweighted κ-values are similar. The implementation of weighted κ-values led to higher scores within all three classification systems, although these did not exceed 0.55 (moderate agreement). Given the high level of consensus, simultaneous pathological assessment may be said to provide added value in comparison with independent assessment. In the current study, no clear tendency is observed in favor of any one classification system. The proposed three-grade system could be an improved histopathological tool because it is easier to correlate with clinical decision making and because it yields better unweighted κ-values and proportions of concordance than the all-options system. Furthermore, clinical management could benefit from assessment by more than one pathologist in suspected cases of dysplasia or carcinoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Laryngeal mucosal premalignant lesions are seen frequently in clinical practice. They are defined as an altered epithelium with an increased likelihood of progression to laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. The altered epithelium shows a variety of cytological and architectural changes that have traditionally been brought under the common denominator of dysplasia.1, 2 Grading of dysplasia, including that of laryngeal lesions, continues to be a topic of debate. It is subjective and has been shown to lack intra- and inter-observer reproducibility, which may have significant therapeutic implications.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 To minimize both morbidity and mortality, it is highly important to detect the lesions at risk for malignancy in its earliest stage.8, 9, 10 Unfortunately, there is no universally accepted histopathological classification system. Moreover, there is no consensus on the diagnostic criteria for the various entities, particularly on criteria to differentiate severe dysplasia from carcinoma in situ. This is illustrated by the fact that during the last decades, more than 20 classification systems have been described for laryngeal mucosal premalignant lesions.3, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 In the current literature and clinical practice, the 2005 World Health Organization, Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and the Ljubljana Classification of Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions systems are the most widely used and are considered the most relevant. So far, the reproducibility of one of these systems, the World Health Organization classification, has been evaluated for laryngeal lesions in just one published study.6 Thus, for the Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Ljubljana systems, no data are available on reproducibility for laryngeal lesions.

The objective of the present study is to reassess the histopathology of previously diagnosed laryngeal mucosal premalignant lesions in order to measure the interobserver variability of the World Health Organization, Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and Ljubljana classification systems and to determine the possible therapeutic consequences of disagreement among observers. Moreover, a proposal to compensate for this variability is made to facilitate the use for clinical purposes.

Materials and methods

To set up an interobserver study on the histopathological assessment of laryngeal mucosal premalignant lesions, three pathologists with head and neck pathology as a field of interest (Marie-Louise van Velthuysen, Freek Bot, and Piet Slootweg) reviewed laryngeal mucosal premalignant lesions cases. Sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) were obtained from the files of the Departments of Pathology at the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center (n=60) and the Maastricht University Medical Center (n=50). The sections represented a range of diagnoses along the spectrum of laryngeal mucosal premalignant lesions. Table 1 gives an overview of the original histopathological diagnoses made according to the World Health Organization classification system.1 The 110 slides were selected by two investigators (Stijn Fleskens and Ewa Bergshoeff) who did not participate as one of the reviewing pathologists. Each pathologist independently reviewed the anonymized 110 microscopic slides without any previous discussion and was completely blinded to the initial diagnosis and grade. No clinical information was provided with the cases. Each slide had to be classified according to the 2005 World Health Organization classification, the Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia classification, and the Ljubljana classification. The criteria they used were derived from the WHO-IARC blue book.1

The World Health Organization classification provides the following options: normal histopathology (hyperkeratosis); inflammation; hyperplasia; mild dysplasia; moderate dysplasia; severe dysplasia; carcinoma in situ; and squamous cell carcinoma. The Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia classification is slightly different: normal histopathology (hyperkeratosis); inflammation; SIN 1; SIN 2; SIN 3; and squamous cell carcinoma. The options in the Ljubljana classification are different again: normal histopathology; inflammation; squamous cell (simple) hyperplasia; basal/parabasal cell hyperplasia; atypical hyperplasia; carcinoma in situ; and squamous cell carcinoma.

To calibrate the categories across the three systems and thus be able to compare the classification systems (Table 2), we used the proposal made in the WHO-IARC blue book and by Gale et al.1, 16 All three pathologists were familiar with the different classification systems. The microscopic slides examined by the reviewers were those on which the initial diagnoses had been made. After the independent assessment, cases with different independent diagnoses were randomly selected on the basis of the all-options system. At a joint meeting, this random selection was assessed by the three pathologists together in order to determine the degree of consensus, which serves as an indicator of the implications of having lesions reviewed by more than one pathologist simultaneously.

Besides comparing all separate options of each system, we designed a two- and a three-grade system (see Table 2) to include clinical management in the histopathological grading.1, 17 The two- and three-grade systems are based on the risk of malignant progression and its consequences for clinical practice: a ‘low-risk’ group, not needing treatment based on grading, and a ‘high-risk’ group, requiring treatment, usually consisting of (laser) surgery or radiotherapy.4, 18, 19 In the ‘high-risk’ group, the three-grade system additionally distinguishes mild and moderate dysplasia from severe dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, and squamous cell carcinoma (World Health Organization); it also distinguishes SIN 1 and 2 from SIN 3 and squamous cell carcinoma (Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia), and it differentiates (atypical hyperplasia) dysplasia from carcinoma in situ and squamous cell carcinoma (Ljubljana). This further differentiation was made because in daily practice normal histology, inflammation, and hyperplasia (green segment in Table 2) are generally considered to require no periodic observation. In contrast, the other histopathological diagnoses do require at least periodic observation (yellow segment in Table 2) and treatment (pink segment in Table 2), respectively.

Statistical Analysis

The κ-statistics were calculated to assess the degree of interobserver agreement in the reporting of all options for each of the three classification systems and the derived two- and three-grade systems. The statistics describe the extent to which observers concur on a diagnosis, adjusted for levels of agreement that are expected to occur by chance alone. The interpretation of κ-values could not rely on any absolute definitions. According to Altman (slightly adapted from Landis and Koch20, 21), κ-values <0.20 indicate poor agreement; 0.21–0.4 fair agreement; 0.41–0.6 moderate agreement; 0.61–0.8 good agreement; and values 0.81–1.00 very good agreement. Standard weighted and unweighted κ-values and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each pair-wise comparison of the three pathologists. Weighted κ-values take into account the amount of disagreement between two raters when a scoring system has three or more categories, which means that more weight is given to a difference of more than one category than to a difference between raters of only one category.22

All analyses were performed with SAS/STAT statistical software (SAS system 8.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Generalized, unweighted κ-values for the three raters and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the SAS macro MAGREE. Finally, the proportion of total concordance among the three raters was calculated for each of the three scoring systems and the derived two- and three-grade systems.

Results

Two cases were excluded from analysis because of insufficient quality of the H&E-stained sections. Two other cases were excluded because of insufficient laryngeal tissue in the H&E-stained sections.

Unweighted and Weighted κ-Values

Table 3 gives an overview of the unweighted and weighted κ-values with 95% confidence intervals.

All options

Comparison of the results using all grading options of the World Health Organization, Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and Ljubljana classification systems yielded the following overall unweighted κ-values: 0.21 (95% confidence interval 0.17–0.26); 0.28 (95% confidence interval 0.23–0.33); and 0.19 (95% confidence interval 0.14–0.24), respectively. Weighted and unweighted κ-values for the pair-wise comparisons of the three are presented in Table 3.

Two-grade system

Comparison of the results for the two-grade system for the World Health Organization, Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and Ljubljana classification systems gave the following overall unweighted κ-values: 0.44 (95% confidence interval 0.33–0. 55); 0.43 (95% confidence interval 0.32–0.54); and 0.50 (95% confidence interval 0.39–0.61), respectively. Weighted κ-values for the pair-wise comparisons of the three observers are presented in Table 3.

Three-grade system

Comparison of the results using the three-grade system for the World Health Organization, Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and Ljubljana classification systems gave overall unweighted κ-values of: 0.39 (95% confidence interval 0.31–0. 47); 0.40 (95% confidence interval 0.32–0.48); and 0.39 (95% confidence interval 0.31–0.47), respectively. Weighted and unweighted κ-values of the pair-wise comparisons of the three observers are presented in Table 3.

Proportion of Concordance

Table 4 shows the proportion of concordance among the pathologists for the three classification systems. The proportions using all grading options of the World Health Organization, Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and Ljubljana classification systems were 13% (95% confidence interval 7–20), 24% (95% confidence interval 16–32), and 17% (95% confidence interval 10–24), respectively. Using the two-grade version of the World Health Organization, Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and Ljubljana classification systems, the proportions of concordance were 60% (95% confidence interval 51–70), 60% (95% confidence interval 51–70), and 62% (95% confidence interval 53–72), respectively. The proportions for the three-grade version of the World Health Organization, Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and Ljubljana classification systems were 42% (95% confidence interval 33–52), 43% (95% confidence interval 34–53), and 47% (95% confidence interval 38–57), respectively.

Simultaneous Pathological Assessment at the Joint Meeting

World Health Organization

A total of 45 cases with different independent diagnoses that had been made on the basis of the all-options system were selected randomly. Consensus could be achieved in 37/45 (82%) of the cases.

Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia

A total of 47 cases with different independent diagnoses based on the all-options system were selected randomly. Consensus could be achieved in 37/47 (79%) of the cases.

Ljubljana

A total of 40 cases with different independent diagnoses made on the basis of the all-options system were selected randomly. Consensus could be achieved in 28/40 (70%) of the cases.

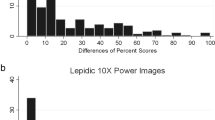

Regarding the World Health Organization and Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia classifications, the clinically relevant differentiation between moderate and severe dysplasia (SIN 2 or 3) was the main source of disagreement. Consensus could not always be reached in these cases, as illustrated in Figure 1. For the Ljubljana classification, the clinically relevant differentiation between (para)basal and atypical hyperplasia turned out to be the most difficult for the raters, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Discussion

In this report, the histopathology of previously diagnosed laryngeal mucosal premalignant lesions was reassessed by three experienced head and neck pathologists. The purpose was to measure the interobserver variability of the three most frequently used classification systems. In this study, these systems have been assessed using all their original categories. Alternatively, a two- or three-grade system has been used, clustering the categories according to the clinical consequences each one would have. When comparing the results of the current study with the literature, we noted that the only available similar study—by McLaren et al,6 based on 100 laryngeal biopsies—published a κ-value of 0.32 using all grading options and 0.52 for a two-grade system using the World Health Organization classification. No 95% confidence intervals were given in that study. In comparison, when we used the World Health Organization classification, we found an overall unweighted κ-value for all options of 0.21 (95% confidence interval 0.17–0.26). Our weighted κ-values ranged from 0.48 (95% confidence interval 0.37–0.58) to 0.50 (0.39–0.60). Using the two- or three-grade system gave an overall κ-value of 0.44 (95% confidence interval 0.33–0.55) and 0.39 (95% confidence interval 0.31–0.47), respectively. The implementation of weighted κ-values led to higher values for all three classification systems. However, they did not exceed 0.55, corresponding with moderate agreement by Altman's criteria.20, 21

Concerning the proportion of concordance for the two- and three-grade system, it should be noted that in 38–40% and 53–58% of the cases, respectively, the three pathologists disagreed. The proposed two- or three-grade system is based on the presumed chance of malignant progression and its implications for clinical practice: ‘low risk’ with mainly periodic observation in comparison with ‘high risk’ requiring (laser) surgery or radiotherapy. By extension, the clinical consequences would be either overtreatment (ie, surgery or radiotherapy instead of periodic observation) or undertreatment (ie, periodic observation instead of surgery or radiotherapy). Either way, the therapeutic implications would be significant. In that light, there is a need for additional tools to identify which lesions would and which would not become malignant if left untreated.

In our review of the literature, we noted that other authors have also proposed or investigated a binary or two-grade system to classify head and neck mucosal premalignant lesions.4, 6, 16, 23 Gale et al16 concluded that the results of a long-term follow-up study of 1268 patients once again justify the proposal of the Ljubljana classification. It entails dividing the morphological criteria into two basic groups: benign (squamous hyperplasia and basal/parabasal hyperplasia) and potentially malignant (atypical hyperplasia). It has been customary to use relatively few categories (three or two) and to assess accuracy by measuring interobserver agreement with κ-statistics. The extent of interobserver agreement is often less than anticipated when carefully controlled studies are undertaken, and there has been a tendency to recommend the use of fewer categories.6, 23, 24, 25, 26 However, according to Deolekar and Morris,24 the policy to lower the degree of inter- and intra-observer disagreement by reducing the number of subjective categories is misleading. Although acknowledging the importance of grading pathological continua, they concluded that information is lost when too few categories are used. The judgment should be cited along with a confidence interval so as not to imply a degree of accuracy that cannot be achieved. Some have argued that it would be logical to use more categories and to give the clinician a range of values within which the true value will lie (a 90, 95, or 99% confidence interval).24, 27 Shannon28 measured information on a binary system. One bit of information reduces uncertainty by one-half, two bits reduce it to one-quarter of the initial level, and three bits reduce uncertainty to one-eighth.

We prefer a three-grade system because of the correlation with daily clinical practice (no periodic observation, periodic observation, and treatment ((laser) surgery or radiotherapy). We would rather avoid the use of only two categories. Furthermore, our current study shows higher unweighted κ-values and proportions of concordance than found with the all-options system.

Comparison of the categories within the different systems has prompted discussion on the position of atypical hyperplasia in the Ljubljana classification. This category showed an overlap with moderate as well as severe dysplasia. Therefore, no optimal discrimination is possible between grades 2 and 3 (yellow and pink segment in Table 2).

In the current study, the highest κ-values for the all-options system are found for the Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia classification, followed by the World Health Organization and Ljubljana classifications. For the two-grade system, the Ljubljana classification has the highest κ-values, followed by the World Health Organization and Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia classifications. The κ-values are similar for the three-grade system. As the 95% confidence intervals show some overlap, as seen in Table 3, no statistically significant (P<0.05) differences are found among the three classification systems. In the future, a similar study based on more cases might demonstrate statistically significant differences.

Furthermore, because of a high level of consensus, the simultaneous pathological assessment had added value in comparison with independent assessment. A consequence could be to advise assessment by more than one pathologist for suspected cases of dysplasia or carcinoma. Similar proposals are found in current guidelines for esophageal and colonic premalignant lesions.29, 30, 31

Montgomery32 suggested that we should look beyond the problem of interobserver variability in the diagnosis of esophageal dysplasia. He thinks that sampling error on the part of endoscopists is probably more serious a problem than observer variation among the pathologists who are reviewing patient samples. However, this possibility would only make the diagnosis of premalignant lesions even less reliable and offers no excuse for the observer variation. In our opinion, the identification of patients with intermediate-level laryngeal dysplasia and high risk of malignancy is a multidisciplinary challenge for both clinician and pathologist, a claim that has been made before.6

The necessity or urgency to treat a laryngeal mucosal premalignant lesion is dependent on several factors: the (voice) complaints of the patient and the risk of progression to invasive cancer or the risk that the sample is not representative for the entire lesion. In the absence of reliable biological markers, the grade of dysplasia is still the most often used parameter to guide the treatment decision. Realizing that clinicians should be aware of the fact that sampling errors may occur and that the determination of the grade of dysplasia is variable. In case of suspicion of a sampling error, a re-biopsy or more extensive surgery should be considered.

Conclusion

In the current study, we have observed no clear tendency in favor of one particular system for classifying laryngeal mucosal premalignant lesions. The weighted κ-values did not exceed 0.55, indicating only moderate agreement and underscoring the assertion that current clinical management is in need of additional tools to identify lesions that would or would not become malignant if left untreated. The proposed three-grade system could be useful because of its correlation with daily clinical practice (no periodic observation, periodic observation, and treatment). Another advantage is that it yields better unweighted κ-values and a higher proportion of concordance in comparison with the all-options system. Moreover, because of a high level of consensus, simultaneous pathological assessment provides added value in comparison with independent assessment. Therefore, assessment by more than one pathologist might be advisable for suspected cases of dysplasia or carcinoma.

References

Gale N, Pilch BZ, Sidransky D, et al. Tumours of the hypopharynx, larynx and trachea (epithelial precursor lesions). In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart, P Sidransky D (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology & Genetics. Head and Neck Tumours. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), IARC Press: Lyon, 2005, pp 140–143.

Haddad RI, Shin DM . Recent advances in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1143–1154.

Blackwell KE, Fu YS, Calcaterra TC . Laryngeal dysplasia. A clinicopathologic study. Cancer 1995;75:457–463.

Fleskens S, Slootweg P . Grading systems in head and neck dysplasia: their prognostic value, weaknesses and utility. Head Neck Oncol 2009;1:1–8.

Johnson FL . Management of advanced premalignant laryngeal lesions. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;11:462–466.

McLaren KM, Burnett RA, Goodlad JR, et al. Consistency of histopathological reporting of laryngeal dysplasia. The Scottish Pathology Consistency Group. Histopathology 2000;37:460–463.

Bosman FT . Dysplasia classification: pathology in disgrace? J Pathol 2001;194:143–144.

Dickman PW, Hakulinen T, Luostarinen T, et al. Survival of cancer patients in Finland 1955–1994. Acta Oncol 1999;38:1–103.

Sadri M, McMahon J, Parker A . Laryngeal dysplasia: aetiology and molecular biology. J Laryngol Otol 2006;120:170–177.

Vokes EE, Weichselbaum RR, Lippman SM, et al. Head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 1993;328:184–194.

Gale N, Kambic V, Michaels L, et al. The Ljubljana classification: a practical strategy for the diagnosis of laryngeal precancerous lesions. Adv Anat Pathol 2000;7:240–251.

Kambic V, Gale N . Significance of keratosis and dyskeratosis for classifying hyperplastic aberrations of laryngeal mucosa. Am J Otolaryngol 1986;7:323–333.

Kambic V . Epithelial hyperplastic lesions--a challenging topic in laryngology. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 1997;527:7–11.

Sengiz S, Pabuccuoglu U, Sarioglu S . Immunohistological comparison of the World Health Organization (WHO) and Ljubljana classifications on the grading of preneoplastic lesions of the larynx. Pathol Res Pract 2004;200:181–188.

Vodovnik A, Gale N, Kambic V, et al. Correlation of histomorphological criteria used in different classifications of epithelial hyperplastic lesions of the larynx. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 1997;527:116–119.

Gale N, Michaels L, Luzar B, et al. Current review on squamous intraepithelial lesions of the larynx. Histopathology 2009;54:639–656.

Dutch Cooperative Head and Neck Group (NWHHT). CBO Revision Guidelines Laryngeal Carcinoma. Van Zuiden Communications: Alphen aan de Rijn, 2009.

Hellquist H, Cardesa A, Gale N, et al. Criteria for grading in the Ljubljana classification of epithelial hyperplastic laryngeal lesions. A study by members of the Working Group on Epithelial Hyperplastic Laryngeal Lesions of the European Society of Pathology. Histopathology 1999;34:226–233.

Fleskens SA, van der Laak JA, Slootweg PJ, et al. Management of laryngeal premalignant lesions in the Netherlands. Laryngoscope 2010;120:1326–1335.

Landis JR, Koch GG . The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–174.

Altman DG . Inter-Rater agreement. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. Chapman & Hall: London, 1991;403–409.

Cohen J . Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull 1968;70:213–220.

Kujan O, Oliver RJ, Khattab A, et al. Evaluation of a new binary system of grading oral epithelial dysplasia for prediction of malignant transformation. Oral Oncol 2006;42:987–993.

Deolekar M, Morris JA . How accurate are subjective judgements of a continuum? Histopathology 2003;42:227–232.

Lang H, Lindner V, de FM, et al. Multicenter determination of optimal interobserver agreement using the Fuhrman grading system for renal cell carcinoma: assessment of 241 patients with >15-year follow-up. Cancer 2005;103:625–629.

Littleford SE, Baird A, Rotimi O, et al. Interobserver variation in the reporting of local peritoneal involvement and extramural venous invasion in colonic cancer. Histopathology 2009;55:407–413.

Morris JA . Information and observer disagreement in histopathology. Histopathology 1994;25:123–128.

Shannon CE . A mathematical theory of information. Bell System Techn J 1948;27:379–423.

Haggitt RC . Barrett's esophagus, dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol 1994;25:982–993.

Lessells AM, Burnett RA, Goodlad JR, et al. Comment on a recent paper and editorial on the subject of dysplasia classification. J Pathol 2002;198:131–132.

Riddell RH . Grading of dysplasia. Eur J Cancer 1995;31A:1169–1170.

Montgomery E . Is there a way for pathologists to decrease interobserver variability in the diagnosis of dysplasia? Arch Pathol Lab Med 2005;129:174–176.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fleskens, S., Bergshoeff, V., Voogd, A. et al. Interobserver variability of laryngeal mucosal premalignant lesions: a histopathological evaluation. Mod Pathol 24, 892–898 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2011.50

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2011.50

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Management of Laryngeal Dysplasia and Early Invasive Cancer

Current Treatment Options in Oncology (2021)

-

Precursor Lesions of the Vocal Cord: a Study on the Diagnostic Role of Histomorphology, Histometry and Ki-67 Proliferation

Pathology & Oncology Research (2020)

-

Laryngeal Dysplasia: Persisting Dilemmas, Disagreements and Unsolved Problems—A Short Review

Head and Neck Pathology (2020)

-

Developing Classifications of Laryngeal Dysplasia: The Historical Basis

Advances in Therapy (2020)

-

Cytokeratin 19 Immunostain Reduces Variability in Grading Epithelial Dysplasia of the Non-Keratinized Upper Aerodigestive Tract Mucosa

Head and Neck Pathology (2020)