Abstract

Tumor-like lesions of the urinary bladder are reviewed emphasizing those that are most diagnostically challenging for the pathologist and may result in serious errors in patient care if misinterpreted. The first category considered, pseudocarcinomatous proliferations, represents an area of bladder pathology only recently appreciated as being particularly treacherous because of the extent to which irregular islands of benign epithelial cells may seemingly penetrate the lamina propria and cause confusion with carcinoma. Somewhat orderly proliferations of this type have been known for years, von Brunn's nests, and are rarely a challenge for the experienced, but proliferations of an irregular nature such as may be seen most often as a result of prior radiation therapy, but sometimes due to chemotherapy or even ischemia, represent a challenging interpretation. The clinical history may be very important in arriving at the correct diagnosis as is the appreciation that the morphology, although architecturally problematic, is different from that of any of the familiar patterns of invasive carcinoma. Florid epithelial proliferations in fibroepithelial polyps are also briefly noted. Within the category of glandular proliferations, emphasis is placed on the wide spectrum of morphology of nephrogenic adenoma including its pseudoinfiltrative pattern and occasional propensity for tiny tubules to be misconstrued as signet-ring cells. The spectrum of müllerian glandular lesions including the relatively recently described mucinous variant, endocervicosis, is reviewed. The reactive papillary proliferation, papillary–polypoid cystitis, is then discussed. This entity has long been known but has recently been re-emphasized. Other non-neoplastic papillary lesions include florid papillary forms of nephrogenic adenoma. The past 25 years has seen a great expansion of knowledge concerning non-neoplastic spindle cell proliferations, including those related to a prior procedure, the postoperative spindle cell nodule and those without such a history, variously designated inflammatory pseudotumor, pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferation, or even other terms. The morphologic spectrum is explored and it is recommended that the two categories be retained.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In this review, I will discuss important areas in differential diagnosis of benign versus malignant in the urinary bladder, covering some time-honored lesions, but ones about which there is, in some instances, new information and a spectrum of other entities, the features of which have largely been appreciated only in recent years. Although, as recently pointed out,1 the split in diagnostic pathology between benign and malignant is to a degree an oversimplification in many situations, in the urinary bladder it is usually very crisp with crucial management issues resting on the pathologic diagnosis. It is not the intent here to be comprehensive, reviews in standard texts that consider the entire spectrum of non-neoplastic lesions being readily available,2 but rather to emphasize the particularly challenging.

The lesions covered are grouped as follows: (1) pseudocarcinomatous proliferations of transitional epithelium; (2) glandular lesions; (3) papillary lesions; (4) spindle cell lesions and (5) miscellaneous others. This approach is used to try and recapitulate the practical situation the pathologist is confronted with at the microscope, namely, an appearance being seen that can potentially have several explanations at least on initial pattern-based review. Before considering the first category, it is interesting to reflect that although the first entity considered is ‘time honored’ the other two lesions have only been identified within the past decade. Not only that, but it is also pertinent to note that in this day and age with much emphasis on techniques such as immunohistochemistry and molecular pathology the important advances reviewed that can greatly impact appropriate patient care have been based on astute light microscopic evaluation taking into consideration the clinical and gross characteristics, two ‘old-fashioned’ aspects of diagnostic pathology that are unfortunately sometimes overlooked in modern practice and yet in this area, as in so many others, are more important than so-called more sophisticated techniques in the great majority of instances.

Pseudocarcinomatous proliferations of transitional epithelium

von Brunn's Nests

The term ‘von Brunn's nests’ refers to the presence of groups of transitional cells in the lamina propria, detached from the overlying urothelium (Figure 1). The nests arise by a process of invagination from the overlying urothelium and the term von Brunn's buds can be used when an attachment to the urothelium is still present. It is the detachment from the overlying epithelium seen in von Brunn's nests that can be problematic, particularly if the nests lie relatively deep in the lamina propria, and are numerous. The cystoscopic impression may be of a tumor,3 which may enhance diagnostic problems. Although the nests of this process are generally rounded and smoothly contoured they may be somewhat irregular.3 The depth of ‘penetration’ into the lamina propria is usually to a uniform depth, often giving a somewhat band-like appearance. Even when invasive carcinoma has relatively bland cytologic features, the cell nests generally have a more disorderly arrangement and more variation in size and shape than von Brunn's nests and sometimes single cells are seen, or at least tiny clusters contrasting with the more numerous cells in the typical von Brunn's nest. Although the bland cytology of the cells in von Brunn's nests in most cases contrasts with the significant atypia seen in most invasive bladder cancers, the epithelium in von Brunn's nests, similar to the surface epithelium, may exhibit hyperplasia and reactive atypia including prominent nucleoli and mitotic activity.

The point at which von Brunn's nests actually cause significant diagnostic confusion is of course related not only to the extent to which the process is conspicuous but also the experience of the examiner. Many readers will have encountered the situation of being shown a case of ‘routine’ von Brunn's nests by a trainee and quickly reassuring and educating them on this well-known benign process. On the other hand, some with significant experience can likely also remember cases in which the interpretation has been a challenge and this is particularly so when there are various other changes common in bladder specimens, such as edema, inflammation and reactive atypia.

Particularly florid epithelial proliferations considered below can be considered variants of von Brunn's nests. They are most typically seen in association with radiation or chemotherapy, but are rarely seen in the absence of such histories. However, in a recent study drawing attention to this phenomenon4 it was noteworthy that in seven of the eight cases there was still a possible etiology for the proliferation in the form of localized ischemia. A diverse array of clinical backgrounds that were thought to be responsible for the ischemia were present in those cases. On the basis of the published photomicrographs, those cases represent a picture broadly speaking similar to those considered in the next section and certainly the changes due to radiation injury prompted recent interest in this overall phenomenon.

Epithelial Proliferations Associated with Radiation or Chemotherapy

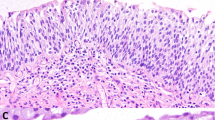

The well-known changes of radiation injury seen elsewhere in the body such as atypia of epithelial cells and so-called radiation fibroblasts in the stroma may be seen in the bladder, but a particularly treacherous facet of radiation injury in the bladder, the formation of so-called pseudocarcinomatous proliferations, has only recently been emphasized.5, 6 In these cases, irregularly shaped and arranged aggregates of epithelial cells in the lamina propria can produce a very confusing picture architecturally (Figure 2). Small pseudopods may heighten the resemblance to carcinoma, and retraction artifact around them may suggest they are sitting in vessels. When the cells show radiation atypia, the potential for confusion with carcinoma is even higher. In such cases, the picture, although worrisome, is not typical of early invasive transitional cell carcinoma and that observation should always prompt a search for other findings consistent with radiation injury, which are typically present. These include radiation fibroblasts, prominent vascular ectasia, abundant fibrin, stromal fibrosis and squamous metaplasia (Figure 3).

Features of the epithelial proliferation in these cases that may be helpful include focal squamous differentiation having a bland glycogenated appearance (contrasting with the neoplastic squamous differentiation often seen in transitional cell carcinoma), and peculiar wrapping of the proliferating epithelial cells around vessels, a feature highlighted in one recent contribution.6 That article also drew attention to the fact that rarely a similar process may be seen in patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Epithelial Proliferations in Fibroepithelial Polyps

The rare fibroepithelial polyp of the bladder may occasionally exhibit a striking epithelial proliferation.7 In the one report of this in the literature, the pattern was likened to that of inverted papilloma but on the basis of the illustrations, in a limited sample, even carcinoma could be mimicked. We have indeed recently seen one case which we feel falls in that category in which the differential diagnosis with a nested carcinoma arose (Figure 4). It was helpful in that case that at cystoscopy a very unimpressive exophytic lesion was not suspicious for cancer and on careful microscopic examination a few atypical stromal cells further caused a fibroepithelial polyp to be considered, and ultimately felt to be the diagnosis. In isolation, as can be seen in the accompanying illustrations, the diagnosis was challenging and the case shows that, depending on the microscopic picture, appropriate emphasis should be given to the gross characteristics in arriving at the final diagnosis. It helped also to have an excellent contribution in the literature to refer to.7

Benign glandular proliferations

Cystitis Glandularis

In its commonest (non-intestinal) form, cystitis glandularis is characterized by glands lined by cuboidal to low columnar cells, which are themselves surrounded by a layer of transitional cells. This process rarely causes concern for malignancy and indeed the converse error, under diagnosing carcinoma with gland differentiation for cystitis glandularis of typical type is probably more common, although still rare. Deviations from an orderly architecture of the type considered in the presentation of von Brunn's nests are again helpful. Although usually a microscopic finding, cystitis glandularis of usual type is occasionally visible grossly as an irregularity but it is almost always less impressive than may be seen in the second, and much less common form of cystitis glandularis, that of intestinal type.2 More worrisome appearing, polypoid, sometimes gelatinous, lesions may be present in these cases and occasionally the radiologic or cystoscopic appearance suggests a malignant tumor.

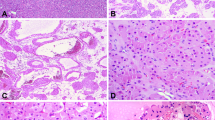

On microscopic examination, the lesion usually occurs in a non-polypoid mucosa, but occasionally an exuberant proliferation produces a papillary or polypoid lesion helping to explain the occasional case, which simulates a neoplasm at cystoscopy. In contrast to the typical form of cystitis glandularis, the cells lining the glands in the intestinal-type cases are tall and columnar with abundant mucin (Figure 5). These cells may be admixed with goblet cells and the epithelium often closely resembles intestinal epithelium; Paneth cells and argentaffin or argyrophil cells are also rarely present. The two types of cystitis glandularis may coexist.

Cystitis glandularis of the intestinal type, although more problematic than the usual type, should uncommonly cause serious diagnostic problems for the pathologist because the atypicality in most adenocarcinomas exceeds that seen in cystitis glandularis and irregular, stromal infiltration generally makes the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma easy. However, cases are encountered in which distinction from adenocarcinoma is difficult. Cases in which there is an irregular disposition of the glands in the stroma, glands deep in the lamina propria and cytologic atypia, even if minor, should be evaluated cautiously as all these features increase the likelihood of the glands being neoplastic. Mucin extravasation may be striking in cases of the intestinal variant of cystitis glandularis (Figure 6).8 In contrast to colloid carcinoma, clusters of epithelial cells are not seen floating in the mucin and the lining epithelium of cysts is not atypical.

The great majority of cases of cystitis glandularis that have been associated with malignancy have been of the intestinal type and the major significance of the intestinal type of cystitis glandularis rests in this association. Mucinuria is a clinical clue to the presence of mucinous metaplasia in some cases and if persistent or prominent, should raise the suspicion of carcinoma, particularly if the clinical setting, such as the presence of a neurogenic bladder, is known to predispose to mucinous metaplasia and subsequent neoplasia. In patients with a non-functioning bladder, mucinous metaplasia may be particularly extensive. In some cases, there has been a very long history of prolonged cystitis glandularis of intestinal type before an adenocarcinoma has evolved. In cases of adenocarcinoma arising on a background of intestinal metaplasia, varying degrees of precancerous atypicality up to adenocarcinoma in situ may be seen.

Nephrogenic Adenoma

This process has generally been thought to be metaplastic, and the terms ‘nephrogenic metaplasia’ or ‘adenomatous metaplasia’ are preferred by some. A recent paper9 suggested that the lesion may actually be of renal tubular origin, something I will not discuss here as it does not bear on the practical benign versus malignant issue. Most cases involve the bladder, with the urethra next most common and ureteral involvement rare.10

Although most common in adults, approximately 10% of the cases have been encountered in children. The great majority of cases are associated with a history of an operative procedure on the genitourinary tract, or one or more irritants including calculi, trauma of various types and cystitis. Additionally, approximately 10% of the patients have had a renal transplant. Associated symptoms are the usual ones encountered in cases of bladder pathology, such as hematuria, frequency or dysuria. It is often unclear whether a given symptom can be attributed to the nephrogenic adenoma, or another aspect of the case such as calculi.

At cystoscopy nephrogenic adenoma may simulate a carcinoma. Approximately 55% of the lesions are papillary, 10% are polypoid, and 35% are sessile. The lesions vary from incidentally discovered microscopic lesions to masses up to 7 cm in greatest dimension. Approximately 60% are 1 cm or less, 30% between 1 and 4 cm and 10% over 4 cm. They are typically single but approximately 20% are multiple; rarely there is diffuse involvement of the bladder.

On microscopic examination, tubular (Figure 7), cystic and polypoid to papillary (see below) patterns are most characteristic. Rare patterns are nested, corded and even spindled (see below). The tubules are small, round and hollow but are occasionally larger, elongated and solid. They are sometimes surrounded by a prominent basement membrane (Figure 8). If present, it can be a helpful diagnostic finding, but I have seen it in only a minority of cases. The tubules frequently undergo varying degrees of cystic dilatation and cysts, which are present in most cases, sometimes predominate. The tubules and cysts may contain an eosinophilic (Figure 9) or basophilic secretion; the latter usually stains weakly positive with the mucicarmine stain. Foci with a diffuse, almost solid growth may be seen in nephrogenic adenomas but are uncommon and always limited in extent. These are due to fusion of tiny tubules with imperceptible lumens imparting a solid appearance except on very close high-power scrutiny.

The majority of the cells lining the tubules and cysts are cuboidal to low columnar with scant cytoplasm, but cells with abundant clear cytoplasm are occasionally present lining these structures and in the solid areas. Hobnail cells focally line the tubules and cysts in about one-third of the cases (Figure 10) and large cysts may be lined by flattened cells. Nuclear atypia is uncommon, and when present appears degenerative in nature; nucleoli may be prominent, however.11 Mitoses are absent or very rare. There is often marked chronic cystitis that may partially obscure the nephrogenic adenoma and rare cases have been associated with prominent stromal calcification.

Several features of the tubular component of nephrogenic adenoma may cause particular diagnostic difficulty and merit emphasis. Tiny tubules containing mucin and apparently lined by a single cell with a compressed nucleus may simulate signet-ring cells (Figure 11). The haphazard distribution of the tubules may also simulate the appearance of an invasive adenocarcinoma (Figure 12), a resemblance that is enhanced when the tubules are admixed with the muscle fibers that may be found in the lamina propria. Hobnail cells may suggest the diagnosis of the rare clear cell carcinoma of the bladder. In males, prostate carcinoma involving the bladder may rarely be an issue. The morphology of prostatic carcinoma and nephrogenic adenoma is usually distinctly different, however, although rarely tubular glands of prostate carcinoma are reminiscent of the tubules of nephrogenic adenoma. If needed immunohistochemistry can help in this regard. Although, treacherously, nephrogenic adenoma can be positive for P504S,12, 13 in contrast to nephrogenic adenoma prostatic adenocarcinoma is positive for PSA and negative for epithelial membrane antigen.13 PAX 8 has recently been shown to stain nephrogenic adenoma but not prostate carcinoma.14 Although they persist and/or recur in about one-third of the cases, nephrogenic adenomas are benign. Evidence presented suggesting that nephrogenic adenoma is a precursor of clear cell carcinoma of the bladder is not convincing in our opinion. That clear cell carcinoma is much more common in the urethra and in women, whereas nephrogenic adenoma is more common in the bladder and in men also argues against such a relationship.

Müllerian Lesions

The bladder is involved in approximately 1% of women with endometriosis and is the commonest site of urinary tract involvement by this disease.15 Up to 50% of the patients have a history of a pelvic operation and in approximately 12% of them evidence of extra-vesical endometriosis is lacking. Vesical endometriosis is commonest in the fourth decade with the average age of 35 years. The microscopic features of endometriosis are so distinctive that confusion with a neoplasm should not be an issue. This is in marked contrast to the other müllerian glandular lesions that are now considered.

Glandular lesions characterized by a prominent component of endocervical-type epithelium may involve the wall of the urinary bladder in women of reproductive age and have been designated ‘endocervicosis.’16 A mass that ranges up to 2.5 cm is typically located in the posterior wall or posterior dome. Microscopic examination typically reveals extensive involvement of the involved bladder wall by irregularly disposed benign appearing or mildly atypical endocervical-type glands, some of which are cystically dilated (Figure 13). Occasionally there are ciliated cells or a minor component of endometrioid glands and glands lined by nonspecific cuboidal or flattened cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm. In some cases, the glands are associated with fibrosis or edema in the adjacent stroma. Rarely, there is some evidence of endometriotic stroma indicating a relationship of this lesion to endometriosis (Figure 14). This and other features such as an occasional association with a history of a cesarean section, indicate that this is a unique müllerian lesion of the bladder and it is best considered the mucinous analog of endometriosis. It is important because lack of awareness of it may lead to confusion with an adenocarcinoma, particularly one of urachal origin. Adenocarcinomas of the bladder, particularly of urachal origin, may have glands lined by tall mucin-rich epithelial cells and as both these cancers and endocervicosis occur at the dome one might think their distinction might be challenging. However, urachal adenocarcinomas, broadly speaking, fall into two groups, overtly infiltrating lesions with obvious malignant characteristics ruling out endocervicosis, or lower grade mucinous cystic lesions with differing gross characteristics. In some cases of benign müllerian lesions, foci of endosalpingiosis are also present and it is rarely striking (Figure 15); when endometriosis and endocervicosis are present as well the designation ‘mullerianosis’ has been suggested.17

Papillary lesions

Papillary–Polypoid Cystitis

I will not consider papillary hyperplasia as, in the great majority of cases, in my opinion, it is a precursor of papillary carcinoma.

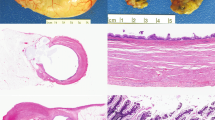

At cystoscopy, or on microscopic examination, papillary–polypoid cystitis may be confused with transitional cell carcinoma.18, 19 The designation papillary cystitis is used when thin finger-like papillae are present, and polypoid cystitis when the lesions are edematous and broad based (Figure 16). There is obvious overlap between the two ends of the spectrum. In both papillary and polypoid cystitis, there is often prominent chronic inflammation in the stroma and blood vessels, some of them ectatic, may be conspicuous. The stroma of papillary–polypoid cystitis varies from edematous, the latter being typical of polypoid cystitis, to more fibrous. When prominently having the latter character and an isolated lesion, it may be arbitrary whether one considers a process polypoid cystitis or a fibroepithelial polyp. As papillary and polypoid cystitis are associated with inflammation, they may be associated with metaplastic changes in the urothelium covering them, or adjacent to them. There are two particular clinical settings, which should suggest that an exophytic bladder lesion may be inflammatory. These are cases in which there is an indwelling catheter and cases of vesical fistula, the latter being particularly treacherous if the clinical history is not provided to the pathologist.

The most important differential diagnosis of papillary and polypoid cystitis is with papillary transitional cell carcinoma. On gross inspection and microscopic examination, the fronds of polypoid cystitis are typically much broader than those of a papillary carcinoma. The thin papillae of papillary cystitis are more difficult to distinguish from carcinoma. In the former (as in polypoid cystitis), the urothelium may be hyperplastic, but usually it is not as stratified as in a carcinoma; additionally, umbrella cells are more often present. The fibrovascular cores of the papillae of a transitional cell carcinoma typically lack the prominent inflammation that characterizes both papillary and polypoid cystitis, and the edema seen in the latter. Large papillae of a transitional cell carcinoma also often give rise to smaller papillae, a feature less commonly seen in papillary or polypoid cystitis.

Other Non-Neoplastic Papillary–Polypoid Lesions

A few of the non-neoplastic lesions already considered may have papillary to polypoid formations and occasionally they are the more striking aspects. This is most typically the case with nephrogenic adenoma (Figures 17 and 18). These are usually associated with at least a minor component of the more common tubular-cystic pattern but rarely one sees only the papillary–polypoid variant. Very delicate filiform papillae may be seen, the other end of the spectrum being more broad-based formations, which occasionally have enough stromal edema to appear polypoid. The cell type is fundamentally the same as seen lining the tubular component of the process, but tends to be more columnar.

Endocervicosis rarely has an intraluminal polypoid component and when viewed in isolation from the more typical mural component may be problematic, albeit its benign nature is usually evident. Nonetheless, the potential for mimicry of a differentiated component of a papillary carcinoma with columnar cell metaplasia exists.

Another rare polypoid lesion is the fibroepithelial polyp. The possible problems caused by epithelial proliferation in such lesions have been presented earlier. An important clue to the diagnosis of this benign lesion can be the presence of the characteristic atypical stromal cells well known when this lesion is, more commonly, seen elsewhere such as in the female genital tract. In one remarkable case, the presence of these cells in considerable number led to sarcoma botryoides being a diagnostic consideration.20 In some cases of fibroepithelial polyp, there may be admixed components of cystitis glandularis and cystitis cystica.

Spindle cell lesions

Non-Neoplastic Stromal Cells with Atypia

Atypical, mononucleated or multinucleated mesenchymal cells are a relatively frequent finding in the lamina propria of the bladder.21 They are relatively common in routine biopsies without obvious evidence of cystitis. The cells often have tapering eosinophilic cytoplasmic processes and may simulate both smooth and skeletal muscle cells. Their nuclei are typically hyperchromatic and often irregular in size and shape, but mitotic figures are typically absent. The cells resemble those that may be seen in the stroma of the female genital tract. Similar cells may be seen in patients treated with chemotherapeutic agents and radiation. These atypical stromal cells occasionally confuse the inexperienced but rarely cause serious diagnostic problems.

Postoperative Spindle Cell Nodule

Much more problematic are florid myofibroblastic proliferations that may form grossly evident masses and that have been a source of recent interest in the literature. There is a trend to group those reactive to a recent procedure, and those not, together. I disagree with this approach because it downplays the importance of the clinical background in surgical pathology, which is a discipline founded on the importance of clinicopathologic correlation. Also, old-fashioned though some may consider it, when an entity is characterized by two of the legendary figures in anatomic pathology, they are owed continuation of ‘their entity’ unless there is pressing evidence that it is doing harm. With that preamble, I will now discuss the two variants, as I see it, the first, because of its crisp clear association with a recent procedure being given precedence.

From the mid-1970s through the early 1980s, Dr Juan Rosai and Dr Robert E Scully saw cases of florid spindle cell proliferations in the genitourinary tract that were usually considered malignant by others but which they thought were benign because of the clinical background and lack of overt atypia. The unifying clinical feature of the cases was the development of the lesions 3 months or less after a surgical procedure had been performed at the site from which the lesional tissue was obtained. Two of the lesions in men were in specimens obtained by transurethral resection (TUR) of the bladder. They each had had a TUR of the bladder performed 2 months previously. At cystoscopy, ‘heaped up tumor’ and a ‘friable vegetant mass’ were noted. The designation postoperative spindle cell nodule was given to the entity when the first report was made in 1984.22

Microscopic examination shows intersecting fascicles of spindle cells (Figure 19), which often show conspicuous mitotic activity. A marked resemblance to a sarcoma, particularly low-grade leiomyosarcoma, often results. Additional microscopic features that are often present include a delicate network of small blood vessels, scattered acute and chronic inflammatory cells, small foci of hemorrhage, mild to moderate edema and focal myxoid change in the stroma. Despite the generally numerous mitotic figures, the cells do not exhibit significant atypia. The clinical association with a recent operation was the major initial clue that these lesions represented an exuberant reactive proliferation. This interpretation was supported by the benign outcome, with conservative management, of most of the initially reported cases and those seen subsequently. Unfortunately, at least one patient in the initial series was radically treated as her physicians elected to proceed according to a malignant diagnosis made by another consultant.

The interpretation of spindle cell lesions of the urinary bladder and in particular the confident diagnosis of a postoperative spindle cell nodule is amongst the most difficult in urologic pathology. Although other sarcomas, such as Kaposi's sarcoma, are occasionally suggested, leiomyosarcoma is usually the major consideration. Distinction from a moderate to poorly differentiated leiomyosarcoma is not difficult as the atypia in these cases exceeds that seen in a postoperative spindle cell nodule (PSCN). However, many well-differentiated leiomyosarcomas do not appear much more atypical cytologically than a PSCN and may be less mitotically active than a PSCN. Although one might expect destructive growth to be helpful in this differential, the PSCN may invade the muscular wall of the bladder. Although leiomyosarcomas may be vascular, the often prominent delicate network of small blood vessels that is seen in many PSCN is, in our opinion, more in keeping with a diagnosis of PSCN than sarcoma (Figure 20). Myxoid change may be seen in both the PSCN and leiomyosarcoma and is not particularly helpful diagnostically, although prominent myxoid change is more in favor of a leiomyosarcoma.

The PSCN may stain positively for cytokeratin.23 Ultrastructural studies of the PSCN are limited but the cells in the few cases studied have been more characteristic of myofibroblasts than smooth muscle cells. Therefore, features of unequivocal smooth muscle differentiation favor a diagnosis of sarcoma in this context, although we would not wish to rely only on this feature to differentiate the two lesions. Ultimately, distinction between these two processes is very dependent on the clinical history of a recent operative procedure. In occasional cases in our experience, it has been impossible to make a confident distinction between them particularly when the interval between a prior operative procedure and the development of a spindle cell lesion is longer (over 3 months) than in most cases of PSCN. In these cases, careful clinical follow-up with repeat cystoscopy and further biopsies is indicated. Conservative excision of a grossly visible lesion is also justified.

Inflammatory Pseudotumor

The first issue to be addressed here is terminology. A variety of terms have been used for this process over the years.24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 Terms such as that used in a recent excellent study ‘Pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferations,’30 seem to have begun to dominate in recent times, but I am not a great enthusiast for that terminology for the following reason. It is at least somewhat similar to the ‘inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor’ used for a separate entity considered neoplastic and typically occurring in children, but with at least some morphologic overlap. I just find this confusing even reading the literature. One of the best early studies of this entity25 used the term inflammatory pseudotumor and to me it is the best available because more likely than not this does have an inflammatory background and it certainly is a pseudotumor in the tradition of using that word for a mass-like lesion that is non-neoplastic.

This lesion may occur at any age but typically occurs in adults in the middle years of life. On gross examination, the majority have had an exophytic character often forming striking polypoid intraluminal masses but occasionally a sessile, endophytic appearance is observed. On microscopic examination, the characteristic microscopic appearance is that of spindle cells typically relatively widely separated in a vascular myxoid stroma (Figure 21). Less commonly there is a more compact cellular non-myxoid appearance (Figure 22). Necrosis and involvement of the muscularis propria may also be seen (Figure 23). Ultrastructural examination has typically shown the features of myofibroblasts. On microscopic examination, the differential diagnosis of this lesion is similar to that of the PSCN, both myxoid sarcomas and myxoid areas in sarcomatoid carcinoma31 occasionally being major considerations. Immunostaining for ALK1 may be of diagnostic aid (Figure 24).32, 33, 34 It should be mentioned that occasional inflammatory pseudotumors, such as the postoperative spindle cell nodule, may be immunoreactive for keratin,27 indeed strikingly so in one recent series.21 The diagnosis of a non-neoplastic mesenchymal lesion in the bladder should be made with great caution in these cases in which there is no history of a recent operation, which is so helpful in cases of PSCN. That having been said, there is no doubt that a sarcoma-like proliferation that is benign occurs in the bladder and irrespective of the preferred designation it is crucial that this be distinguished from malignant processes for obvious therapeutic and prognostic reasons.

Miscellaneous Other Spindle Cell Lesions

This paragraph is included to enable me to briefly mention that a spindle cell pattern has recently been described in cases of nephrogenic adenoma.35 In all these cases of so-called ‘fibromyxoid nephrogenic adenoma,’ the classic tubular pattern was also present but the predominance in some cases of spindle cells within a fibromyxoid background led to diagnostic problems (Figures 25 and 26). It is important to be aware of this rare aspect of the histopathology of nephrogenic adenoma and particularly when there is any history that may have elicited this peculiar process diligent search for the more characteristic patterns should be carried out.

Miscellaneous Other Tumor-Like Lesions

An array of other lesions such as ectopic prostate, the very rare hamartoma of the urinary bladder, and amyloidosis, may present clinically as mass lesions and result in the procurement of tissue for microscopic examination. There is no new information, to the best of my knowledge, on these uncommon conditions that have been reviewed elsewhere.2 A similar comment pertains to abnormalities of the urachus. One recent contribution on vascular tumors and tumor-like lesions of the bladder has included three cases of intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (so-called Masson's lesion).36 As elsewhere in the body these could potentially be confused with a vascular neoplasm, even sarcoma, and the criteria enumerated in various treatises on soft tissue tumors will be helpful in this circumstance.

References

Rosai J . The benign versus malignant paradigm in oncologic pathology: a critique. Semin Diagn Pathol 2008;25:147–153.

Young RH . Non-neoplastic disorders of the urinary bladder. Chapter 5 In: Bostwick DG, Cheng L (eds). Urologic Surgical Pathology 2nd edn. Mosby Elsevier, 2008, pp 215–256.

Volmar KE, Chan TY, DeMarzo AM, et al. Florid von Brunn nests mimicking urothelial carcinoma. A morphologic and immunohistochemical comparison to the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:1243–1252.

Lane Z, Epstein JI . Pseudocarcinomatous epithelial hyperplasia in the bladder unassociated with prior irradiation or chemotherapy. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:92–97.

Baker PM, Young RH . Radiation-induced pseudocarcinomatous proliferations of the urinary bladder: a report of 4 cases. Hum Pathol 2000;31:678–683.

Chan TY, Epstein JI . Radiation or chemotherapy cystitis with ‘pseudocarcinomatous’ features. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:909–913.

Tsuzuki T, Epstein JI . Fibroepithelial polyp of the lower urinary tract in adults. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:460–466.

Young RH, Bostwick DG . Florid cystitis glandularis of intestinal type with mucin extravasation: a mimic of adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:1462–1468.

Mazal PR, Schaufler R, Altenhuber-Muller R, et al. Derivation of nephrogenic adenomas from renal tubular cells in kidney-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 2002;347:653–659.

Oliva E, Young RH . Nephrogenic adenoma of the urinary tract: a review of the microscopic appearance of 80 cases with emphasis on unusual features. Mod Pathol 1995;8:722–730.

Cheng L, Cheville JC, Sebo TJ, et al. Atypical nephrogenic metaplasia of the urinary tract: a precursor lesion? Cancer 2000;88:853–861.

Skinnider BF, Oliva E, Young RH, et al. Expression of α-methylacyl-CoA racemase (P504S) in nephrogenic adenoma. A significant immunohistochemical pitfall compounding the differential diagnosis with prostatic adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:701–705.

Xiao GQ, Burstein DE, Miller LK, et al. Nephrogenic adenoma. Immunohistochemical evaluation of its etiology and differentiation from prostatic adenocarcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006;130:805–810.

Tong GX, Weeden EM, Hamele-Bena D, et al. Expression of PAX8 in nephrogenic adenoma and clear cell adenocarcinoma of the lower urinary tract. Evidence of related histogenesis? Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:1380–1387.

Clement PB . Diseases of the peritoneum In: Kurman RJ (ed). Blaustein's Pathology of the Female Genital Tract 5th edn. Springer Verlag: New York, 2002, pp 729–789.

Clement PB, Young RH . Endocervicosis of the urinary bladder. A report of six cases of a benign müllerian lesion that may mimic adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1992;16:533–542.

Young RH, Clement PB . Mullerianosis of the urinary bladder. Mod Pathol 1996;9:731–737.

Young RH . Papillary and polypoid cystitis. A report of eight cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1988;12:542–546.

Lane ZL, Epstein JI . Polypoid/papillary cystitis: a series of 41 cases misdiagnosed as papillary urothelial neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:758–764.

Young RH . Fibroepithelial polyp of the bladder with atypical stromal cells. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1986;110:241–242.

Wells HG . Giant cells in cystitis. Arch Pathol 1938;26:32–43.

Proppe KH, Scully RE, Rosai J . Postoperative spindle cell nodules of genitourinary tract resembling sarcomas. A report of eight cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1984;8:101–108.

Wick MR, Brown BA, Young RH, et al. Spindle-cell proliferations of the urinary tract. An immunohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol 1988;12:379–389.

Roth JA . Reactive pseudosarcomatous response in urinary bladder. Urology 1980;16:635–637.

Nochomovitz LE, Orenstein JM . Inflammatory pseudotumor of the urinary bladder––possible relationship to nodular fasciitis. Two case reports, cytologic observations, and ultrastructural observations. Am J Surg Pathol 1985;9:366–373.

Albores-Saavedra J, Manivel JC, Essenfeld H, et al. Pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferations in the urinary bladder of children. Cancer 1990;66:1234–1241.

Jones EC, Clement PB, Young RH . Inflammatory pseudotumor of the urinary bladder. A clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and flow cytometric study of 13 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1993;17:264–274.

Lundgren L, Aldenborg F, Angervall L, et al. Pseudomalignant spindle cell proliferations of the urinary bladder. Hum Pathol 1994;25:181–191.

Iczkowski KA, Shanks JH, Gadaleanu V, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor and sarcoma of urinary bladder: differential diagnosis and outcome in thirty-eight spindle cell neoplasms. Mod Pathol 2001;14:1043–1051.

Harik LR, Merino C, Coindre JM, et al. Pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferations of the bladder. A clinicopathologic study of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:787–794.

Jones EC, Young RH . Myxoid and sclerosing sarcomatoid transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 25 cases. Mod Pathol 1997;10:908–916.

Cessna MH, Zhou H, Sanger WG, et al. Expression of ALK1 and p80 in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor and its mesenchymal mimics: a study of 135 cases. Mod Pathol 2002;15:931–938.

Hirsch MS, Cin PD, Fletcher CDM . ALK1 expression in pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferations of the genitourinary tract. Histopathology 2006;48:569–578.

Tsuzuki T, Magi-Galluzzi C, Epstein JI . Alk-1 expression in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the urinary bladder. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:1609–1614.

Hansel DE, Nasasdy T, Epstein JI . Fibromyxoid nephrogenic adenoma: a newly recognized variant mimicking mucinous adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:1231–1237.

Tavora F, Montgomery E, Epstein JI . A series of vascular tumors and tumorlike lesions of the bladder. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:1213–1219.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclosure/conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Young, R. Tumor-like lesions of the urinary bladder. Mod Pathol 22 (Suppl 2), S37–S52 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2008.201

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2008.201

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Intestinal metaplasia of the urinary tract harbors potentially oncogenic genetic variants

Modern Pathology (2021)