Abstract

Integrated circuit technologies are enabling intelligent, chip-based, optical packet switch matrices. Rapid real-time re-configurability at the photonic layer using integrated circuit technologies is expected to enable cost-effective, energy-efficient, and transparent data communications. InP integrated photonic circuits offer high-performance amplifiers, switches, modulators, detectors, and de/multiplexers in the same wafer-scale processes. The complexity of these circuits has been transformed as the process technologies have matured, enabling component counts to increase to many hundreds per chip. Active–passive monolithic integration has enabled switching matrices with up to 480 components, connecting 16 inputs to 16 outputs. Integrated switching matrices route data streams of hundreds of gigabits per second. Multi-path and packet time-scale switching have been demonstrated in the laboratory to route between multiple fibre connections. Wavelength-granularity routing and monitoring is realised inside the chip. In this paper, we review the current status in InP integrated photonics for optical switch matrices, paying particular attention to the additional on-chip functions that become feasible with active component integration. We highlight the opportunities for introducing intelligence at the physical layer and explore the requirements and opportunities for cost-effective, scalable switching.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cloud-based services, video traffic, enterprise applications, and virtualisation have led to a relentless rise in traffic in optical communications networks1. In turn, this is leading to unsustainable energy usage and an increasing complexity in network control2–4. Optical packet routing and switching technologies offer the prospect of highly efficient networking that is attuned to packet-based traffic flows4. However, to date the underlying photonic hardware has not proved sufficiently scalable, and the physical layer performance has been impeded by the analogue nature of the underlying photonic components.

Photonic switch matrices and wavelength-selective switches already provide energy-efficient connectivity at the highest bandwidths for circuit-provisioned time-scales. The optical switching engines that are now being deployed in telecom networks and data centre networks are based on slow (millisecond) circuit-switching technologies that leverage micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS)5,6 and liquid crystal on silicon7,8 switch elements. 3D MEMS systems now allow for connectivity between many hundreds of fibre connections9,10. The combination of broadband photonic switches and wavelength-selective diffractive optical elements offers even higher connectivity. However, the use of surface normal micro-optics introduces considerable assembly complexity as the connectivity scales. The switching speeds do not support packet-based traffic at the optical layer.

Planar photonic integrated circuits have long held the promise of high-speed broadband connectivity with mass-manufactureable microchips11, but only recently has the technology12 matured to the point that circuits with sufficient numbers of components can be realised. Photonic integrated circuits enable not only switching solutions for high capacity data but also support the components required to support loss compensation, dynamic reconfigurability, power equalisation, channel monitoring, and multicasting.

In this work, we review the progress made in electronically actuated, monolithic switching circuits. The methods used for creating these circuits have been reported elsewhere13–15, and we focus here on circuit-level functionality. In section ‘Monolithic Optical Switch Architectures’, we review the integration technologies that have enabled high-connectivity routing in planar optical and optoelectronic circuits. We then focus on circuits that exploit the InP integrated photonics platform. In section ‘Broadband photonic packet switching matrices’, we address broadband implementations with demonstrations of up to 320 Gb s−1 line rates, packet time-scale reconfigurability and connectivity of up to 16 ports in a packet-compliant switching matrix. A study of the circuit-level gain, loss, and noise performance provides insight into the future scalability of these circuits. In section ‘Wavelength-selective packet switching matrices’, we address developments in the scaling of monolithically integrated wavelength- and space-selective elements. We identify opportunities for wavelength-granularity operations such as optical label routing and in-line monitoring. We discuss the possibilities and challenges for future deployment in the ‘DISCUSSION’ section and offer an outlook in the last section.

Monolithic Optical Switch Architectures

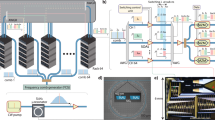

Planar integrated circuit technologies have been implemented with a wide range of switch architectures and electronically actuated methods. These range from thermo-optic and electro-optic methods for controlling loss, gain, and refractive index through the electrostatic movement of waveguides. A broad range of established techniques using interferometric and gated switch elements have also been reported16–18. Here we focus specifically on switch circuits that can be scaled in capacity and connectivity. Table 1 chronologically highlights prominent examples, specifying circuits in terms of their architectures, materials, actuation mechanisms, and connectivity. Figure 1 shows schematic implementations for the range of circuits reviewed.

Cascaded 2 × 2 switch elements19–28, as shown in Figure 1a, enable increasing connectivity through the concatenation of additional switching stages. Such switches can be readily implemented with a combination of relatively long phase modulators within 2 × 2 Mach-Zehnder interferometers. Early work was performed using Lithium Niobate Ti:LiNbO3, Silica, and SiON technologies. The former enabled the exploitation of fast electro-optic phase modulation within Mach-Zehdner interferometers. Switch matrix connectivities of 16 × 1619 and 32 × 3220 were demonstrated early on through multistage networks but achieving high extinction ratios in broadband switch elements has proven challenging. Double-stage switch elements provide enhanced extinction22. Switch elements used in combination with semiconductor optical amplifier (SOA) gates offer an even smaller footprint28. The physical size of electro-optic phase modulators has led to circuit path lengths of a few centimetres for the earlier examples, but technology advances driven by high-performance InP modulators have allowed sub-millimetre-length phase shifters with low voltage actuation29. Thermo-optic phase shifters for Silicon on Insulator switches with 8 × 8 connectivity have led to a footprint of 3.5 × 2.4 mm2 24 and circuits with connectivities of up to 32 × 3225, but thermo-optic actuation has not been sufficiently fast for packet-based traffic. Compact current injection, Mach-Zehnder switches offer a route to faster reconfigurability30. Here the Mach-Zehnder switch elements are implemented with passband-broadened couplers with bandwidths greater than 75 nm. However, critical phase matching is required for broadband operation. A need for on-chip amplification has been identified for further scaling in connectivity18.

The cross-point architecture31–35, which uses an array of orthogonal input and output guides, is shown schematically in Figure 1b. The architecture uses compact switch elements that readily scale. 1 × 2 elements can be effectively used at the intersection, with ultra-low-loss off-state losses for high scalability. Silica planar light wave circuits have been used in combination with thermally actuated bubble-switch elements to achieve connectivities up to 32 × 32. Connections are made by total internal reflection at trenched intersections and broken by infilling the trenches with an index-matched fluid31. Planar integrated MEMS have been deployed in combination with twin-guide planar circuits to create monolithic 50 × 50 photonic switch matrices32. An electrostatically actuated MEMS waveguide is moved to enable a directional coupling between the input and output buses32. These waveguides are low-loss and broadband, with a compact footprint of 7.6 × 7.6 mm2, although the actuation voltages are still relatively challenging at the low tens of volts. Ring resonator elements have been considered extensively, given the increased availability of silicon on insulator technology for photonic circuits. Placing rings at the intersections between the input and output busses allows wavelength-specific routing through thermo-optic tuning33. Higher order ring resonators offer a flattened-passband response that enables wavelength-tolerant, broadband routing in a cross-grid array34. Faster actuation has proven more challenging with cross-point architectures generally because the physical size of the switching elements has largely precluded the use of fast electro-optic switching. One potential exception is the vertically coupled SOA switch concept, which has been scaled to 4 × 4 connectivity35.

Broadcast and select techniques offer the prospect of multicast routing at the chip level, and connectivity can be scaled by means of multiple interconnected stages36. An equivalent path-to-path connection is also feasible in the wavelength domain by means of wavelength conversion37. An example is shown in Figure 1c. Splitters and combiners have enabled up to 16 connections. Work on one-to-many switches has led to the demonstration of 1 × 16 connectivity for broadband phase array switches38 and 1 × 100 connectivity for an integrated two-stage circuit comprising a combination of phase arrays and SOA gates39. N × N switch matrices require shuffle networks with waveguide crossings and the additional associated optical wiring complexity. However, this complexity can be tractable using lower radix broadcast and select elements in multistage architectures. An all-amplifying 16 × 16 circuit has been implemented with three stages of four 4 × 4 switch-building blocks to demonstrate the first lossless 16 × 16 port count optical switches36. The electrical power consumption of the all-active chip is estimated to be 12 W for a fully operational circuit with a moderate power density of 0.3 W mm−2. Approximately half of the required electrical power is required to bias the split and shuffle elements at transparency. The use of an all-active epitaxy also degrades the noise performance and limits the optical input power dynamic range. Recently, we have demonstrated active–passive integrated circuits with 16 × 16 connectivity, leading to improvements in optical signal-to-noise performance14. These results are reviewed in further detail in section ‘Broadband photonic packet switching matrices’ to provide insights into the potential for scaling and performance.

Wavelength-selective switching (WSS) can be performed within planar waveguide monolithic circuits. Programmable Mach-Zehnder filter chains40 and gated arrayed waveguide grating filters41 have both been studied. The earliest wavelength blockers using SOA gates were implemented with 1 × 1 physical connectivity and up to 100 wavelength on-chip selectivity42. An example implementation is shown in Figure 1d, where the splitters and combiners have been replaced with wavelength de/multiplexers. Scaling to N × N with on-chip wavelength selectivity offers a powerful route towards very high levels of connectivity. The possibility to connect arbitrary wavelength combinations with a combination of broadcast and select switches and wavelength-selective switches enables a functionality that approaches that of (modest-connectivity) multi-degree reconfigurable optical add drop multiplexing. This can be achieved through the combination of de/multiplexers and broadband combiners. Circuits with 4 × 4 connectivity for four wavelengths43 and more recently 8 × 8 with eight wavelengths15 have now been implemented with this concept within 1 cm2 of an InP chip and are reviewed in section ‘Wavelength-selective packet switching matrices’. The use of on-chip amplifiers additionally enables a path to optical lossless, multi-cast functionality and a broad range of control and monitoring functions.

Broadband photonic packet switching matrices

Monolithically integrated photonic switches introduce considerable flexibility and bandwidth but without wavelength-scale granularity. SOA gate switches enable passbands of several Terahertz, enabling colourless and wavelength-multiplexed routing with 1–2 V actuation levels. In the on state, the signals are amplified, and in the off state, they are strongly attenuated. As the data throughput is not directly linked to the actuation energy, such broadband switches are expected to enable considerable energy savings with respect to electronic switching as line rates increase. This motivates the study of highline-rate signal routing.

320 Gb s−1 line rate routing

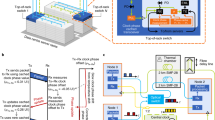

The first multistage SOA-based switch using active–passive InP regrown wafers was implemented with an N-stage planar design using a cascaded 2 × 2 crossbar switch elements. Figure 1a shows the architecture for the four-input, four-output switching matrix. Figure 2a shows the circuit, which was fabricated as part of a multi-project wafer (MPW) run to study high serial line rate data transmission in such multistage networks44. The crossbar elements were implemented with broadcast and select switches. The gold pads visible in Figure 2a are the electrodes, which are used for controlling the 2 × 2 crossbar switch elements. For convenience, the optical connections are made from the same front facet, and the electronic connections to the SOA gates are made to a PCB on the right side of the photograph.

Integrated, four-input, four-output multistage switching network produced in an MPW run44: (a) photograph of the switch circuit and (b) highline-rate routing through the circuit. The power penalty is shown as a function of increasing line rate. The solid line shows predictions for noise-limited performance. The solid symbols show the experimentally measured data. The open symbols represent data simulated with the large-signal numerical model. The inset shows the experimental eye diagram measurement for 320 Gb s−1 line rate routing.

The performance of the switch was originally studied in terms of the power penalty with increasing line rate and an increasing number of switching stages, to better understand the physical limitations in ultrahigh line rate optoelectronic integrated circuits. Custom test beds were implemented and used to analyse the signal degradation over a range of line rates from 40 Gb s−1 and 160 Gb s−1 44 to 320 Gb s−1 45. For a worst case electrical power consumption per gate of 0.2 W, four 320 Gb s−1 channels could in principle be routed with a power of 1.2 W, which corresponds to a sub-pJ/bit energy budget. It should be noted that the energy consumption is bit-rate independent for switches of this class, and the efficiency improves with increased throughput. Signal impairments may be anticipated through such circuits, and they will increase as the signal propagates through additional 2 × 2 switch elements. By comparing the signal quality before and after the switch for different numbers of switch stages and line rates, it becomes possible to develop an insight into the scaling properties of the switch matrix, both in terms of capacity and connectivity.

A bit error-rate analysis was performed for the three different line rates and different numbers of integrated switch elements to study signal quality degradation mechanisms. Figure 2b shows the power penalty for 40, 160, and 320 Gb s−1 for two- and four-switch stages. The inset shows a measured, open eye diagram for the 320 Gb s−1 signal, which has been routed through four stages of integrated crossbar switches. The power penalty is negligible for modest 40 Gb s−1 line rates, but the signal quality degrades as the line rate increases to 160 Gb s−1 and above. The power penalty incurred through the switching network may be expected to degrade through nonlinearities in the SOA gates and the build-up of additional noise in the circuit. Two models were used to predict and quantify the precise contributions to the signal degradation46. A large-signal model47 was implemented to simulate the combined effects of the SOA nonlinearity and noise as a function of the line rate, and the simulated data points are shown using open symbols. A small signal model48 was also applied to predict the noise-incurred power penalty, and this is shown using a solid line. Shot noise, signal–spontaneous beat noise and spontaneous–spontaneous beat noise were defined consistently with the large-signal model parameters. The equivalent noise figure for each amplifier stage for the optimum on-state condition was 6.5 dB, and the gain for each on-state SOA gate was assumed to equal the 7 dB passive component loss from the splitter–combiner pair in the 2 × 2 switch element. A comparison of the experimental data with the noise model and the large-signal model indicates that performance to 320 Gb s−1 appears to be noise limited. However, higher line rates are expected to be impacted by the higher mean input powers associated with higher line rates, and this is expected to lead to gain saturation and patterning in the output data stream. Wavelength multiplexing schemes might be considered to achieve higher aggregate throughputs.

Dynamic routing with nanosecond reconfiguration times

The full demonstration of packet routing in integrated optical switch matrices requires an abstraction of the photonic physical layer from the control plane. The most efficiently implemented form of abstraction has been realised with fast current driver arrays in combination with a round-robin scheduler. Figure 3a shows an integrated 4 × 4 broadcast and select switching matrix to demonstrate packet time-scale connectivity. Data were input to each of the four optical inputs, and the time traces were recorded for all the optical outputs. The round-robin scheduler enabled combinations of paths to be sequenced on a 3.2 µs time slot49. Figure 3b shows the output time trace from the first output. The independent level control for each of the SOA gates enabled on-chip optical power levelling. The complete circuit required only one time slot clock input signal to synchronise with the external network. Multiple gate states were simultaneously defined to allow the full utilisation of the fabric.

Large-scale switching matrices using multiple stages of switch elements require more complex switching algorithms, look-up tables, and level control, which motivate the use of programmable logic for the schedulers and level control. This has been implemented50 for subsequent work on 8 × 8 and 16 × 16 connectivity switching matrices. Arrays of fast (nanosecond) current drivers were connected to the SOA selector gates of the integrated cross-connect to enable path and channel selection. The current levels for each of the SOA selector gates were separately programmed by arrays of digital-to-analogue converters and a central microcontroller. An Altera Stratix III field programmable gate array provided time-slotted control signals to the nanosecond rise time current drivers for optical path selection50. A lack of on-chip optical buffering limited operation to time slot schemes, but the precise duration of the time slots was programmable51. This electronic control plane has more recently been implemented to enable time slot–resolved error-rate measurements during scheduled multi-path operation in an 8 × 8 switching fabric52. Flow control has also been implemented for more distributed control planes53.

16 × 16 connectivity in a monolithic switch

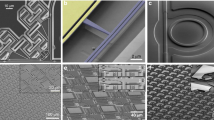

High-radix 4 × 4 SOA-based switch elements can be efficiently configured in multistage networks to enable high connectivity with a limited number of stages. Three switch stages provide a good compromise between optical wiring complexity, signal integrity, and control complexity. A monolithic 16 × 16 connectivity switch has been implemented with active–passive integration14. A composite microscope photograph is shown in Figure 4. The input and output waveguides for the circuits are visible at the facets on a 250 µm grid at the left and right edges of the circuit, respectively. The circuit comprised an input stage of 2 × 2 switch arrays on the left and an output stage of 2 × 2 switch arrays on the right. These were interconnected with two planes of 4 × 4 switch arrays. The 4 × 4 switches with loss-compensated broadcast and select capability enabled multicast both at a switch element level and at the circuit level. A total of 192 active SOA gates were integrated with 188 passive splitters and combiners within a circuit area of 4.0 × 13.2 mm, which created one of the most complex circuits in its class to date. Connections were feasible from any port to any port, with just three SOA gates on any path. The additional switching plane at the centre stage allowed for two different paths for each input–output combination to enable a rearrangeable nonblocking design.

Measurements of circuit performance were used to analyse the path-dependent characteristics in terms of gain, loss, and noise. Inputs 1 and 16 were electronically programmed to connect to each of outputs 1 through to 16. The longest and shortest path lengths and a representative range of intermediate path lengths through the circuit were analysed by comparing the circuit’s input and output signal and noise levels using an optical spectrum analyser. Figure 5a shows the fibre-to-fibre signal loss when moving from path 1-to-1 to path 1-to-16 (open circles). The fibre-to-fibre signal losses increased as the path length and complexity increased. This is quantitatively consistent with the additional incurred losses for the longer paths, as shown by the predicted losses in Figure 5a. The broadcast-enabled architecture incurred 30 dB of optical loss because ten 3-dB optical splitter–combiners were present in any given path. An additional gain from the SOA gates compensated for much of the excess component loss. Figure 5b shows the optical signal-to-noise performance for the same paths ranging from 28.3 to 13.7 dB 0.1 nm−1 for a mean, in-fibre, input optical power of −2.1 dBm. A direct correlation can be observed between path loss and the degradation in the optical signal-to-noise ratio. Although these values are encouraging, one might expect a lower loss and improved noise performance with three stages of on-chip SOAs gates. A circuit-level analysis was therefore performed using component-level performance data from separate test structures and circuits using comparable fabrication techniques.

Performance analysis for 16 × 16 switching matrices. (a) Fibre-to-fibre losses, (b) optical signal-to-noise ratio. Input reference (green dotted line), measured performance (red circles), predicted performance (red solid line), and projected performance (blue dashed line) with component optimisations per Table 2.

The circuit-level losses were analysed by evaluating the losses in comparable circuits and through direct measurement. The two values for the component losses are summarised in Table 2. The first set of values are for the component types implemented in the 16 × 16 switching circuit and the second set of values are those that have been achieved in separately optimised chips. The predicted performance for the implemented circuit elements (solid line) and the projected performance with optimised circuit elements (dashed lines) are shown in Figure 5. The agreement for the implemented elements is excellent, giving confidence that the loss and noise performance of the circuits can be clearly attributed to the excess losses of the components.

The noise performance was predicted by estimating the optical power map for the signal and noise within the switch matrix circuit and including the additional amplified spontaneous emission noise contributed at each SOA gate. Each of the three stages of the SOA gates in the circuit was expected to operate with a mean gain of 12.9 dB and a mean amplified spontaneous emission power density of −47.3 dBm 0.1 nm−1. The operating optical input power was −21 dBm, so the 500-µm-long gates were operated far from the optical saturation power. The electrical bias conditions were 75 mA and 1.5 V.

The component-level excess losses are summarised in Table 2, and although they may appear to be modest for each component, the combination of the high numbers of components in each path, long waveguide lengths and the two fibre-to-chip couplings led to high levels of circuit-level excess losses, which were 30 dB and above. However, the losses can be significantly reduced. For example, mode-size adaption at the facets may be expected to reduce fibre-to-chip coupling to 1.5 dB per connection54. Low parasitic reflection splitters operating with only 0.2 dB excess loss55 would lead to a net loss reduction of 3 dB. The number of crossing is significant, varying from 7 to 26, but the loss per crossing may be reduced by an order of magnitude through a broadening in the intersecting waveguides56. Waveguide losses of approximately 0.5 dB cm−1 may be expected when the level of p-doping is minimised in the passive waveguides57. Such optimisations of excess losses have been shown to enable lossless circuit-level operation and will also have a radical impact on the optical signal-to-noise ratio, reducing the optical signal-to-noise ratio to 50.3 to 49.2 dB per 0.1 nm. This would be equivalent to a circuit-level noise figure of 9.7 dB, of which 5.5 dB is attributable to losses between the input side fibre and the first SOA gate.

Wavelength-selective packet switching matrices

The integration of wavelength switching functions within monolithic photonic switches enables additional control and connectivity, while retaining the same level of optical fibre connectivity. This offers a powerful combination of wavelength, time, and space domain switching on a single chip. Packet-reconfigurable multi-wavelength routers can be implemented by combining a demultiplexer, gate array, and broadband combiner. The underlying concept was first prototyped in integrated form for packet routing applications with a 1 × 4 gated cyclic router connecting four ports with wavelength-selective SOA gates58. The 4 × 4 circuit43 replicates this concept four times and interconnects the circuits with a 4:16 split-and-shuffle network and space-selective SOA gates. This is shown in Figure 6a. Thirty-two active components were integrated with 24 splitters and combiners and four cyclic routers to achieve 64 possible paths through the circuit. This circuit has now been used to demonstrate multi-path 40 Gb s−1 routing59 and multistage routing through the same circuit60. This repeated circulation indicates the possibility for further scaling at the network level. Higher on-chip 8 × 8 connectivity has also been achieved using the same technology platform and architecture15. The split-and-shuffle network on the left of Figure 6b was scaled up to 8:64 by doubling the number of inputs and adding an additional preamplifier and splitter stage. Eight 8 × 8 cyclic routers combined with a gate array on the right-hand side of the circuit enabled the wavelength selection functionality. A number of wavelength routing measurements have been performed, including dynamic multi-cast routing and wavelength-multiplexed packet routing with low power penalty50,52. The inclusion of on-chip de/multiplexing also introduces opportunities for on-chip signal monitoring and remotely reconfigured switching.

Optical label routing

Remotely configured, WSS is performed using the SOA gates as both monolithically integrated label readers and channel selectors. Here the dual functionality of an SOA array can be exploited to either detect labels or gate routed signals. A proof-of-principle experimental demonstration was performed using our first monolithically integrated photonic integrated 1 × 4 wavelength and space-selective switch61.

In the experimental proof-of-concept, which is shown schematically in Figure 7a, two data wavelengths were controlled by one out-of-band optical label. This allowed the fast remote configuration of the WSS state for the two test data wavelengths. The presence or absence of the optical-label wavelength defined which of the two data channels passed through the circuit. More sophisticated routing algorithms are also feasible for higher numbers of channels and ports. For the dynamic routing studies, the pattern trigger signal from the bit error-rate tester was used to create a square wave modulation for the control channel. The switch state toggled between high and low with 819.2 ns time slot. This was sufficiently long to enable gated error measurements under dynamic label routing conditions. The time traces show, from top to bottom, the remotely generated control signal, the gate signals to the SOAs, and the resulting time-interleaved wavelengths. The optical label wavelength actuated the gates for the two incoming data wavelengths, which led to the successful time multiplexing of the two data streams seen in the lower time trace.

On-chip optical performance monitoring

As switching matrices become more complex and interconnected, it becomes important to monitor the optical signal quality as data pass through the switching matrices. Recently, we proposed and demonstrated a scheme for on-chip optical signal-to-noise ratio (OSNR) monitoring62. One output path from the space- and wavelength-selective switch was re-purposed for performance monitoring using the same component set and circuit configuration as shown in Figure 8a. The final stages of the SOA gates are now used to monitor signal and noise power, respectively. The distribution of the SOA gates before and after the cyclic router enabled the on-chip calibration of the OSNR meter, which further enabled pre-calibration and, potentially, in-service calibration, depending on the mode of operation.

In-line OSNR monitoring demonstrated with an 8 × 8 space- and wavelength-selective switch. (a) Circuit configuration, (b) comparison of the on-chip and off-chip optical signal-to-noise measurements. The differences between the on-chip (blue line) and off-chip (red line) measurements were used to calculate the final SOA gate noise figure (open circles).

The pre-calibration was performed using the central-stage SOA gates as broadband light sources. The photocurrents measured at the preamplifier SOAs and the wavelength-selective SOA gates yielded the broadband and filtered integrated optical power, which was used to calculate a noise power spectral density correction factor. Under live-traffic conditions, packets may be intermittently copied or routed to the OSNR meter for the measurement of signal and noise powers. In principle, this analysis can be performed in real time and at the packet level.

An experimental validation of the concept is shown in Figure 8a. The uppermost space selecting SOA routed the signal under test to the uppermost wavelength-selective plane. However, in this case the wavelength-selective SOA gates were implemented as photodiodes. The outputs were connected to trans-impedance amplifiers instead of fast current drivers. The output voltage was recorded and calibrated to give the optical signal-to-noise ratio shown in Figure 8b. To verify the technique, a comparison was made between the OSNR values that were measured using the on-chip method and values directly measured using an optical spectrum analyser connected via the output waveguide and the final-stage SOA gate. The measured OSNR varied from 0 to 40 dB per 0.1 nm, depending on the optical input power to the circuit. The values exceeded 30 dB per 0.1 nm for in-fibre, input optical powers exceeding −9 dBm. A strong correlation can be observed between the on-chip and off-chip measurements, although there was a clear offset between the two measurements of 3.9 to 5.3 dB. This offset corresponds to the anticipated noise figure of the wavelength-selective SOA gate, which needs to be included for the off-chip measurement. This was forward biased at 40 mA, with an estimated input power of −16.8 dBm and a gain of 8.2 dB.

Discussion

Optical packet switching matrices may be expected to offer a compelling alternative to the combination of electronic fabrics with optical transceiver interfaces when the photonic integrated circuits are transparent, scalable, manufacturable, and network compliant. Energy and cost advantages may be anticipated as line rates scale through the use of extensive optical multiplexing.

Transparent operation requires the minimisation of noise, signal-induced distortion and inter-channel crosstalk. Gain and noise are linked, but as shown in this work, the use of modest-connectivity, loss-less switch elements in a multistage architecture does provide a means to optimise the optical power distribution in the circuit with manageable levels of noise. The noise figures anticipated in this work are 4–6.5 dB for each integrated semiconductor optical amplifier, which will allow scalable, loss-less, and multistage circuits63. The input side fibre-chip coupling loss dominates the circuit-level noise figure, which provides a strong motivation for further integration. The polarisation-independent performance is attractive because it enables the use of standard fibres and polarisation-multiplexed transceivers. Polarisation-independent operation has long been feasible for individual semiconductor optical amplifiers, de/multiplexers, and splitters, but it will be challenging to ensure wide-band operation under all operating conditions for complex circuits using reconfigured combinations of many such components. Switch technologies that rely on directional coupling, electro-optic modulation, or grating techniques will be more challenging to implement in a polarisation-independent manner. On-chip polarisation handling may offer more scalable and manufacturable approaches.

Scaling to many tens of connections is conceivable from an optical power-map and optical power dynamic range perspective63, but crosstalk levels and switch extinction ratios will need to be controlled64. For example, the current wavelength-selective switch designs appear to be limited by wavelength channel crosstalk levels of the order of 20 dB in nonoptimised de/multiplexers15. Integration density is not currently a limiting factor, and component counts have already been scaled to 1700 devices in the most advanced WDM devices65. Integrated de/multiplexers similarly scale to several tens of channels. Thermal loading will influence design. To date, the electrical input energy is approximately 16 W even for all-active lossless 16 × 16 switch fabrics36, but active–passive integration and component optimisations will lead to further electrical power reductions for lossless, circuit-level operation. On-chip routing and shuffling of connections may prove to be more challenging in the absence of a multi-level optical wiring solution.

Manufacturability will require all components to meet loss, extinction, and crosstalk specifications across the full operational bandwidth and at sufficient yields to meet product-pricing requirements. This will be challenging, but it is worth noting that satisfactory yield–performance metrics have been achieved in the highly demanding telecom transceiver market using advanced InP integrated photonics66. Critical dimension variations may be expected to become increasingly important with circuit scaling. Potentially important advances include the use of whispering gallery regimen waveguiding for reproducible, low-radius microbends67, precision-fabricated, low-loss de/multiplexers, low-reflection splitters, and manufacturable polarisation controllers68. Deep-UV lithography can enable both tighter dimensional control and also lower loss, lower crosstalk de/multiplexer components that will be important for wavelength-selective architectures. Nevertheless, larger numbers of concatenated components will lead to a narrowing of the operating regimens, which will impact the yield–performance specification and ultimately determine the most attractive levels of chip-level connectivity.

Networking requirements will call for further innovations in control and synchronisation. Integration does simplify scheduling through the near-negligible delays between components, but routing algorithm complexity still scales rapidly with connectivity69. Burst mode transceiver technology will play a key enabling role in the currently conceived optical packet switch systems. The evolution from low rates to tens of Gb s−1 performance has been well documented for passive optical networks70. Burst-mode operation of up to 25 Gb s−1 is feasible for the reconfiguration time-scales envisaged for passive optical networks71, and a route towards 40 Gb s−1 links has been identified72. Efficient packet-based networks will, however, require shorter reconfiguration times. In the first optical packet demonstrations, 25.6 ns preambles and 25 ns guard times were used for the error-free reception of asynchronous 10 Gb s−1 packets73; 25 Gb s−1 burst mode receiver technology specifically for optical packet switching is now also beginning to emerge from industry research laboratories74,75. Gated oscillator and oversampling techniques for clock and data recovery are identified as methods to further reduce the preamble and guard time requirements76.

Outlook

InP integrated photonic circuits offer a powerful route to combining advanced routing and signal-processing functions onto one chip. Throughputs with line rates of 320 Gb s−1 have been demonstrated with multistage networks, and circuit connectivity has scaled to 16 ports. Further connectivity scaling is achievable with on-chip wavelength routing. To realise key cost–performance advantages, further integration will be necessary, and new components will need to be introduced12 to enable higher circuit densities, efficiencies, and polarisation handling. The requirements for reduced energy use, lower latency and lower cost for increasing data rates are expected to continue and lead to sustained pressure on sub-system integration. The photonic components used are analogue in nature, but this needs to be abstracted to enable tractable network-level implementations. Multicast capability, packet time-scale reconfigurability, power levelling irrespective of signal path, distributed signal quality monitoring, and data rate transparency can be implemented at the chip level, which will enable an abstracted digital control plane. Achieving this level of signal processing may have impact beyond the immediate pressure points in data communications and find potential new applications from sensor readout technologies to optical beam-forming technologies.

References

The zettabyte era: Trends and analysis. Cisco White Paper, 2015. http://www.netmode.ntua.gr/courses/postgraduate/video_communications/2014/VNI_Hyperconnectivity_WP.pdf. (accessed at 1 December 2015).

Kilper DC, Atkinson G, Korotky SK et al. Power trends in communication networks. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2011; 17: 275–284

Kilper DC, Guan K, Hinton K et al. Energy challenges in current and future optical transmission networks. Proceedings of the IEEE 2012; 100: 1168–1187.

Yoo SJB . Energy efficiency in the future internet: The role of optical packet switching and optical-label switching. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2011; 17: 406–418.

Marom D, Neilson DT, Greywall DS et al. Wavelength-selective 1 × K switches using free-space optics and MEMS micro mirrors: Theory, design, and implementation. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2005; 23: 1620–1630.

Wu MC, Solgaard O, Ford JE . Optical MEMS for lightwave communication. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2006; 24: 4433.

Wall P, Colbourne P, Reimer C et al. WSS switching engine technologies. Conference on Optical Fiber communication/National Fiber Optic Engineers Conference 2008 (OFC/NFOEC 2008); 24–28 Feb 2008; San Diego, CA, USA; 2008: 1–5.

Baxter G, Frisken S, Abakoumov D et al. Highly programmable wavelength selective switch based on liquid crystal on silicon switching elements. Optical Fiber Communication Conference and Exposition and The National Fiber Optic Engineers Conference, 2008; 5 Mar 2006; Anaheim, CA, USA; 2006: doi: 10.1109/OFC.2006.215365.

Yamamoto T, Yaguchi J, Takeuchi N et al. A three-dimensional MEMS optical switching module having 100 input and 100 output ports. IEEE Photonics Technology Letters 2003; 15: 1360–1362.

Zheng X, Kaman V, Yuan S et al. Three-dimensional MEMS photonic cross-connect switch design and performance. Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2003; 9: 571–578.

Doerr C . Planar lightwave devices for WDM. In: Kaminov IP, Li T, editors. Optical Fiber Telecommunications IVA Components. Academic Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA; 2002: 402–477.

Meint Smit, Jos van der Tol, Martin Hill . Moore’s law in photonics. Laser & Photonics Reviews (special issue) 2012; 6: 1–13.

Smit MK, Leijtens XJM, Ambrosius HPMM et al. An introduction to InP-based generic integration technology. Semiconductor Science and Technology 2014; 29: 2908–3001.

Stabile R, Albores-Mejia A, Williams KA . Monolithic active-passive 16 × 16 optoelectronic switch. Optics Letters 2012; 37: 4666–4668.

Stabile R, Rohit A, Williams KA . Monolithically integrated 8 × 8 space and wavelength selective cross-connect. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2013; 32: 201–207.

Renaud M, Bachmann M, Erman M . Semiconductor optical space switches. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 1996; 2: 277–288.

Williams KA . Integrated semiconductor-optical amplifier-based switch fabrics for high-capacity interconnects. Journal of Optical Networking 2007; 6: 189–199.

Lee BG, Dupuis N, Pepeljugoski P et al. Silicon photonic switch fabrics in computer communications systems. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2015; 33: 768–777.

Duthie PJ, Wale MJ . 16×16 single chip optical switch array in lithium niobate. Electronics Letters 1991; 27: 1265–1266.

Okayama H, Kawahara M . Prototype 32 × 32 optical switch matrix. Electronics Letters 1994; 30: 1128–1129.

Rabbering FLW, van Nunen JFP, Eldada L . Polymeric 16 × 16 digital optical switch matrix. 27th European Conference on Optical Communication (ECOC ’01)2001; 30 Sep–4 Oct 2001; 6: 78–79.

Goh T, Yasu M, Hattori K et al. Low loss and high extinction ratio strictly non-blocking 16 × 16 thermooptic matrix switch on 6-in wafer using silica-based planar lightwave circuit technology. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2001; 19: 371–379.

Lee BG, Rylyakov A, Green WMJ et al. Four and eight port photonic switches monolithically integrated with digital CMOS logic and driver circuits. Optical Fiber Communication Conference/National Fiber Optic Engineers Conference 2013; 17–21 Mar 2013; Anaheim, CA, USA; 2013: doi: 10.1364/NFOEC.2013.PDP5C.3.

Suzuki K, Tanizawa K, Matsukawa T et al. Ultra-compact 8 × 8 strictly-non-blocking Si-wire PILOSS switch. Optics Express 2014; 22: 3887–3894.

Tanizawa K, Suzuki K, Toyama M et al. Ultra-compact 32 × 32 strictly-non-blocking Si-wire optical switch with fan-out LGA interposer. Optics Express 2015; 23: 17599–17606.

Kouketsu H, Kawasaki S, Koyama N et al. High-speed and compact non-blocking 8 × 8 InAlGaAs/InAlAs Mach-Zehnder-type optical switch fabric. Optical Fiber Communication Conference 2014; 9–13 Mar 2014; San Francisco, CA, USA; 2014: doi: 10.1364/OFC.2014.M2K.3.

Cheng Q, Wonfor A, Wei JL et al. Low-energy, high-performance lossless 8×8 SOA switch. Optical Fiber Communication Conference 2015; 22–26 Mar 2015; Los Angeles, CA, USA; 2015: doi: 10.1364/OFC.2015.Th4E.6.

Cheng Q, Wonfor A, Penty RV, et al. Scalable, low-energy hybrid photonic space switch. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2013; 31: 3077–3084.

Griffin RA, Jones SK, Whitbread N et al. InP Mach–Zehnder modulator platform for 10/40/100/200-Gb/s operation. Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2013; 19: 3401209.

Lee BG, Rylyakov AV, Green WMJ . Monolithic silicon integration of scaled photonic switch fabrics, CMOS logic, and device driver circuits. Journal Lightwave Technology 2014; 32: 743.

Venkatesh S, Son JW, Fouquet JE et al. Recent advances in bubble-actuated photonic cross-connect switches. SPIE Proceedings, 4654: doi: 10.1117/12.463854.

Han S, Seok TJ, Quack N et al. Large-scale silicon photonic switches with movable directional couplers. OSA Optica 2015; 2: 370–375.

Ji R, Xu J, Yang L . Five-port optical router based on microring switches for photonic networks-on-chip. Photonics Technology Letters 2013; 25: 492.

Das Mahapatra P, Stabile R, Rohit A, et al. Optical crosspoint matrix using broadband resonant switches. Journal of Selected Topics Quantum Electronics 2014; 20: 5900410.

Varrazza R, Djordjevic IB, Yu S . Active vertical-coupler-based optical crosspoint switch matrix for optical packet-switching applications. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2004; 22: 2034–2042.

Wang H, Wonfor A, Williams KA et al. Demonstration of a lossless monolithic 16 × 16 QW SOA switch. 35th European Conference on Optical Communication (ECOC 2009); 20–24 Sep 2009; Vienna, Austria; 2009.

Nicholes SC, Masanovic ML, Jevremovic B et al. An 8 × 8 InP monolithic tunable optical router (MOTOR) packet forwarding chip. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2010; 2: 641–650.

Soganci IM, Tanemura T, Williams KA et al. Monolithically integrated InP 1 × 16 optical switch with wavelength-insensitive operation. IEEE Photonics Technology Letters 2010; 22: 143–145.

Soganci IM, Tanemura T, Nakano Y . Integrated phased-array switches for large-scale photonic routing on chip. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2012; 6: 549–563.

Stabile R, Calabretta N, Williams KA . Switch-filter wavelength selector: Simulation and experiment. IET Optoelectronics 2014; 8: 1–10.

Calabretta N, Williams KA, Dorren HJS . Monolithically integrated WDM cross-connect switch for nanosecond wavelength, space, and time switching. 2015 European Conference on Optical Communication (ECOC); 27 Sep–1 Oct 2015; Valencia, Spain; 2015: doi: 10.1109/ECOC.2015.7341615.

Kikuchi N, Shibata Y, Okamoto H et al. Monolithically integrated 100-channel WDM Channel selector employing low-crosstalk AWG. Photonics Technology Letters 2004; 16: 2481–2483.

Rohit A, Bolk J, Leijtens XJM, et al. Monolithic nanosecond-reconfigurable 4 × 4 space and wavelength selective cross-connect. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2012; 30: 2913.

Albores-Mejia A, Gomez-Agis F, Zhang S et al. Monolithic multistage optoelectronic switch circuit routing 160Gb/s line-rate data. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2010; 28: 2984–2992.

Albores-Mejia A, Gomez-Agis F, Dorren HJS et al. 320Gb/s data routing in a monolithic multistage semiconductor optical amplifier switching circuits. 36th European Conference and Exhibition on Optical Communication; 19–23 Sep 2010; Torino, Italy; 2010: doi: 10.1109/ECOC.2010.5621383.

Albores Mejia A . High capacity photonic integrated switching circuits. PhD thesis. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, 2011. https://www.tue.nl/en/publication/ep/p/d/ep-uid/257064/. 2011.

Olsson NA . Lightwave systems with optical amplifiers. Journal of Lightwave Technology 1989; 7: 1071–1082.

Stabile R, Wang H, Wonfor A et al. Multipath routing in a fully scheduled integrated optical switch fabric. 36th European Conference and Exhibition on Optical Communication; 19–23 Sep 2010; Torino, Italy; 2010: doi: 10.1109/ECOC.2010.5621152.

Stabile R, Rohit A, Williams KA . Dynamic multi-path WDM routing in a monolithically integrated 8 × 8 cross-connect. Optics Express 2014; 22: 435–442.

Stabile R, Albores-Mejia A, Williams KA . Dynamic multi-path routing in a monolithic active-passive 16 × 16 optoelectronic switch. Optical Fiber Communication Conference 2013; 17–21 Mar 2013; Anaheim, CA, USA; 2013: doi: 10.1364/OFC.2013.OM3K.5.

Cheng Q, Stabile R, Rohit A et al. First demonstration of automated control and assessment of a dynamically reconfigured monolithic 8×8 wavelength-and-space switch. Journal of Optical Communications and Networking 2015; 7: A388–A395.

Di Lucente S, Luo J, Rohit A et al. Optical packet switch node with packet flow control for flat inter-cluster data center network. Optical Fiber Communication Conference and Exposition and the National Fiber Optic Engineers Conference 2013; 17–21 Mar 2013; Anaheim, CA, USA; 2013: 1–3.

Langley LN, Robbins DJ, Williams PJ et al. DFB laser with integrated wave-guided taper grown by shadow masked MOVPE. Electronics Letters 1996; 32: 738–739.

Kleijn E, Melati D, Melloni A et al. Multimode interference couplers with reduced parasitic reflections. Photonics Technology Letters 2014; 26: 408–410.

Bukkems HG, Herben CGP, Smit MK et al. Minimization of the loss of intersecting waveguides in InP-based photonic integrated circuits. Photonics Technology Letters 1999; 11: 1420–1422.

D’ Agostino D, Carnicella G, Ciminelli C et al. Low loss waveguides for standardized InP integration processes. Proceedings IEEE Photonics Society Benelux, Twente, The Netherlands; 2014.

Rohit A, Williams KA, Leijtens XJM et al. Monolithic multiband nanosecond programmable wavelength router. Photonics Journal 2010; 2: 29–35.

Rohit A, Albores-Mejia A, Bolk J et al. Multi-path routing at 40Gb/s in an integrated space and wavelength selective switch. 2011 IEEE Photonics Conference; 9–13 Oct 2011; Arlington, VA, USA; 2011: 342.

Rohit A, Albores-Mejia A, Bolk J et al. Multi-hop dynamic routing in an integrated 4 × 4 space and wavelength select cross-connect. Optical Fiber Communication Conference and Exposition 2012 and the National Fiber Optic Engineers Conference; 4–8 Mar 2012; Los Angeles, CA, USA; 2012: 1–3.

Rohit A, Albores-Mejia A, Calabretta N et al. Fast remotely reconfigurable wavelength selective switch. Optical Fiber Communication Conference 2011; 6–10 Mar 2011; Los Angeles, CA, USA; 2011: doi: 10.1364/OFC.2011.OTuM1.

Stabile R, Williams KA . Optical power meter co-integrated with a fast optical switch for on-chip OSNR monitoring. 2015 International Conference on Photonics in Switching (PS); 22–25 Sep 2015; Florence Italy; 2015: 360–362.

Williams KA, Aw ET, Wang H et al. Physical layer modelling of semiconductor optical amplifier based terabit/second switch fabrics. Proceedings of the Numerical Simulation of Optical Devices, Nottingham, UK, Post-deadline paper ThPD5; 2008.

Stabile R, Williams KA . Photonic integrated semiconductor optical amplifier switch circuits. In: Advances in optical amplifiers. Intech; 2011: 205–230. www.intechopen.com.

Summers J, Vallaitis T, Evans P et al. Monolithic InP-based coherent transmitter photonic integrated circuit with 2.25 Tbit/s capacity. Electronics Letters 2014; 50: 1150.

Kish F, Nagarajan R, Welch D et al. From visible light-emitting diodes to large scale III-V photonic integrated circuits. Proceedings of the IEEE 2013; 101: 2255–2270.

Stabile R, Williams KA . Relaxed dimensional tolerance whispering gallery microbends. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2011; 29: 1893–1898.

Williams KA, Bente EAJM, Heiss D et al. InP photonic circuits using generic integration. Photonics Research 2015; 3: B60–B68.

Luijtens R, Grzybowski R . The OSMOSIS optical packet switch for supercomputers. Optical Fiber Communication Conference 2009; 22–26 Mar 2009; San Diego, CA, USA; 2009: doi: 10.1364/OFC.2009.OTuF3.

Qiu XZ, Yin X, Verbrugghe J et al. Fast synchronisation burst mode receivers for passive optical networks. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2014; 32: 644–659.

Yin X, Verbist J, de Keulenaer T et al. 25Gb/s 3-level burst mode receiver for high serial rate TDM-PONs. Optical Fiber Communication Conference 2015; 22–26 Mar 2015; Los Angeles, CA, USA; 2015: doi: 10.1364/OFC.2015.Th4H.2.

Yin X, Qiu XZ, Torfs G et al. New developments in critical components for 40Gb/s long reach passive optical networks. Proceedings Progress in Electromagnetics Research Symposium; 25–28 Aug 2014; Guangzhou, China; 2014.

Miao W, Yin X, Bauwelinck J et al. Performance assessment of optical packet switching system with burst-more receiver for intra-data center networks. 2014 European Conference on Optical Communication; 21–25 Sep 2014; Cannes, France; 2014: 1–3.

Nada M, Nakamura M, Matsuzaki H . 25-Gbit/s burst-mode optical receiver using high-speed avalanche photodiode for 100-Gbit/s optical packet switching. Optics Express 2014; 22: 443–449.

Rylyakov A, Proesel J, Rylov S et al. A 25 Gb/s burst-mode receiver for low latency photonic switch networks. Optical Fiber Communication Conference 2015; 22–26 Mar 2015; Los Angeles, CA, USA; 2015: doi: 10.1364/OFC.2015.W3D.2.

Melange C, Baekelandt B, Bauwelinck J et al. Burst mode CDR performance in long-reach high-split passive optical networks. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2009; 27: 3837–3844.

Acknowledgements

The work has been supported by the Dutch technology foundation STW. Two of the circuits were produced on MPW runs by the technical staff at the COBRA institute. MPW runs are supported at jeppix.eu. We thank T. de Vries for technical advice during the fabrication of the remaining circuits. Q. Cheng and A. Wonfor are also acknowledged for valuable discussions with regard to multi-path routing experiments. F. Gomez-Agis is acknowledged for his role in the development of the 320-Gb s−1 optical test-bed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Stabile, R., Albores-Mejia, A., Rohit, A. et al. Integrated optical switch matrices for packet data networks. Microsyst Nanoeng 2, 15042 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/micronano.2015.42

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/micronano.2015.42

This article is cited by

-

Kinetics and mechanism of the sulfurization behavior of silver conductive material in automobile industry

Rare Metals (2022)

-

Graphene-based integrated photonics for next-generation datacom and telecom

Nature Reviews Materials (2018)

-

Modular architecture for fully non-blocking silicon photonic switch fabric

Microsystems & Nanoengineering (2017)