Abstract

During gaseous exchange the lungs are exposed to a vast variety of pathogens, allergens, and innocuous particles. A feature of the lung immune response to lung-tropic aerosol-transmitted bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is a balanced immune response that serves to restrict pathogen growth while not leading to host-mediated collateral damage of the delicate lung tissues. One immune-limiting mechanism is the inhibitory and anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-10. IL-10 is made by many hematopoietic cells and a major role is to suppress macrophage and dendritic cell (DC) functions, which are required for the capture, control, and initiation of immune responses to pathogens such as Mtb. Here, we review the role of IL-10 on bacterial control during the course of Mtb infection, from early innate to adaptive immune responses. We propose that IL-10 is linked with the ability of Mtb to evade immune responses and mediate long-term infections in the lung.

Similar content being viewed by others

TUBERCULOSIS AND Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb): BACKGROUND

Tuberculosis (TB) is predominantly a disease of the lungs; however, dissemination of the pathogen to other disease sites does occur but depends on productive infection of the lungs. The current figures for 2009 (see ref. 1) show that TB is once more on the increase; globally, there is a large burden of disease with ∼9.4 million new cases (of which 1.1 million cases were in human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals) and 1.7 million deaths annually (of which 0.4 million were in human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals). Following infection, alveolar macrophages phagocytose the pathogen but are unable to efficiently kill all the invading Mtb bacilli, giving rise to a host–pathogen equilibrium where a small percentage of bacilli survive the antimicrobial cascade elicited by host immune cells. The infection is controlled in part by walling it off from the rest of the uninfected lung in radiographically distinct foci known as granulomas; Mtb persists within these foci in the unfused phagosomes of macrophages, giving rise to a latent infection.2, 3 Recent evidence from the Mycobacterium marinum model of TB infection suggests that recruitment of macrophages into a nascent granuloma is a mechanism used by mycobacteria to facilitate intercellular spread.4, 5, 6 As such, TB granulomas might be a trade-off that benefits both host and pathogen.2

On average, a vast majority of individuals exposed to Mtb mount an efficient cell-mediated immune response culminating in a so-called latent infection with no clinical signs of disease. However, the remaining ∼5–10% of individuals will progress to active disease as demonstrated by culturable bacilli from the sputum and the development of clinical symptoms.1 Although a number of mechanisms have been described for the development of a protective immune response that restricts and controls infection and thus prevents progression to active disease, the reasons underlying active disease progression remain poorly understood. Based on its properties it is likely that interleukin-10 (IL-10) may contribute to TB pathogenesis. Here, we outline the key elements in the immune response to Mtb with emphasis on stages where IL-10 can limit or subvert the protective immune responses mounted by the host following infection (summarized in Figure 1).

Potential checkpoints in the regulation of the immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection by interleukin-10 (IL-10). 1=Inhibition of macrophage killing and dendritic cell (DC) uptake, processing, and presentation; 2=regulation of DC migration from the site of infection to local draining lymph nodes in order to drive naive T-cell polarization toward a TH1 interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-producing phenotype; 3=suppression of chemokines involved in Th1 migration and trafficking of cells from the draining lymph node back to the lungs, for example, C-X-C motif chemokine 10 (CXCL10); and 4=IFN-γ activation of macrophage antimicrobial pathways. Modified from Redford et al. (2010), “IL-10 suppresses early protective TH1 responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis”. Eur. J. Immunol. 40: 2078–2079. doi: 10.1002eji.201090039.

PROTECTIVE FACTORS IN THE IMMUNE RESPONSE TO Mtb: EVIDENCE FROM MOUSE AND MONKEY MODELS, AND HUMANS

The essential requirement for the IL-12/T helper type 1 cell (TH1) axis in the control of mycobacterial infections has been observed in patients exhibiting MSMD (Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases; reviewed in ref. 7). Mutations in genes encoding the IL-12 receptor render individuals extremely susceptible to intracellular pathogens such as atypical mycobacteria8, 9, 10 and pulmonary TB (PTB).11 Similarly, mutations in the interferon-γ receptor 1 (IFN-γR1) and its key downstream signaling molecule STAT1 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 1) also render individuals extremely susceptible to PTB,12 Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG),13, 14 and environmental mycobacteria.15, 16, 17, 18 CD4+ T cells are essential in the immune response to Mtb as reported in humans co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus/Mtb,19, 20, 21 and as further supported by non-human primate studies22 and mouse models,23, 24, 25 whereby in their absence, the host rapidly succumbs to infection. The importance of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in the control of human TB was realized when rheumatoid arthritis patients latently infected with Mtb received anti-TNF therapy, which led to TB reactivation.26 In line with the observations in humans, the importance of TNF-α in preventing reactivation of latent TB has also been shown in non-human primate studies27 and mouse models.28, 29 The findings in human genetic studies highlighting the importance of IFN-γ and IL-12 have also been demonstrated in mouse models of Mtb. Mice deficient in IFN-γ,30, 31 IL-12,32, 33, 34 or TNF-α35, 36 succumb early to Mtb infection with high bacterial loads. The IL-12/CD4/IFNγ/IFNγR/STAT1 axis is crucial for the IFN-γ activation of infected macrophages to facilitate bacterial killing; however, the overall antimycobacterial mechanisms in humans remain unknown. In this review we first outline the basic functions of IL-10, which collectively can result in negative regulation of such factors, which have been demonstrated to be protective against Mtb infection.

IL-10: BACKGROUND

More than 20 years ago, the cytokine IL-10 was identified as a “cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor,” a product of TH2 clones following protein or antigen stimulation, that blocked cytokine production from TH1 clones.37 IL-10 achieved this effect by inhibiting the ability of myeloid cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) to activate TH1 cells.38 We now know that IL-10 is not just made by Th2 cells, but can be produced by most if not all CD4+ T-cell subsets, including TH1 and TH17 cells, B cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and some DC subsets.39 Regulatory T cells (Tregs), in the context of infectious disease, also serve as a major source of immunoregulatory IL-10 and, depending on their developmental origin, may come in several forms (reviewed in refs. 39, 40, and 41). Thymic and inducible Tregs expressing the transcription factor FoxP3+ (FoxP3+ Treg) can suppress effector responses through the soluble factors transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and IL-10, as well as via cell–cell contact mechanisms such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4; reviewed in refs. 39 and 42). FoxP3+ Tregs have been shown during Mtb infection to limit host T-cell accumulation in the lungs and restrict subsequent effector responses; however, it is not clear whether they achieve these effects via the action of IL-10.43, 44 Naive CD4+ T cells may also be induced in the periphery as either (i) FoxP3+ inducible Tregs or FoxP3− IL-10-secreting Tr1-like Tregs, for example in the gut, in the presence of microenvironmental stimuli such as TGF-β and retinoic acid, or (ii) FoxP3− IL-10-producing TH1 cells, as has been shown during infection with Leishmania45 or Toxoplasma46 (reviewed in refs. 39, 41, and 42).

IL-10 signals through a receptor complex consisting of two subunits: IL10R1, induced on stimulated hematopoietic cells, and the IL10R2, constitutively expressed on most cells and tissues.38 These receptor subunits transduce signals through the Janus kinase (Jak)–STAT pathway via Jak1 in the mouse and Jak1 and tyrosine kinase 2 (Tyk2) in humans, culminating in tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of STAT3, as well as STAT1, and in nonmacrophage cells, STAT5 (reviewed in refs. 38 and 39). However, the genetic and biochemical evidence from both mouse and human systems implicates STAT3 as the sole STAT required to generate the IL-10 inhibitory signal.47, 48, 49

Induction of IL-10 in cells of the innate and adaptive immune response

IL-10 is produced by both myeloid cells and T cells. In myeloid cells, IL-10 is induced following Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligation in response to a plethora of pathogen products. The magnitude of IL-10 induction within different myeloid cell types has been linked to the relative strength of extracellular signal-related kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) activation.50 For example, macrophages activate high amounts of ERK in comparison with myeloid DCs, which activate intermediate amounts; this is in contrast to plasmacytoid DCs that have low ERK activation and ultimately cannot make IL-10. However, cytokine production by plasmacytoid DCs in response to TLR ligation can be significantly inhibited when exogenous IL-10 is added to cell cultures.51

The induction of IL-10 in myeloid cells in response to TLR ligands requires the signaling adaptor molecules MyD88 (myeloid differentiation primary response gene (88)), Toll-IL-1 receptor (TIR) domain-containg adaptor inducing IFN-β (TIR-containing adaptor molecule-1), and a plethora of indirect pathways mediated by autocrine/paracrine factors.39, 51, 52, 53 MyD88 is crucial in the control of Mtb infection;54, 55 however, studies in mice focusing specifically on TLR-associated protection suggest that TLR/MyD88 signaling pathways may not be essential (reviewed in ref. 56) and instead that IL-1β/IL-1R1/MyD88-dependent pathways function to control Mtb infection.57 These findings reflect the overall complexity of the signaling cascades involved.

In addition to IL-10 induction by TLR-dependent stimuli, IL-10 can also be induced from innate cells such as DCs via TLR-independent stimuli including C-type lectin receptors, via the spleen tyrosine kinase-dependent pathway.58 IL-10 can be induced in neutrophils in response to Mtb through CARD9 (caspase recruitment domain family, member 9)59 or to BCG by activation of spleen tyrosine kinase, leading to phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases and serine/threonine Akt kinases.60 Alternatively, stimulation through CLEC4M (DC-SIGN) via activation of RAF161 also leads to IL-10 production in response to Mtb. Furthermore, C-type lectin receptor stimulation in the presence of FcγR ligation62 or CD40 triggering63 can further potentiate the production of IL-10.

IL-10 production by CD4+ T cells after TH differentiation requires sustained ERK1/2 phosphorylation,64 where IL-10 expression is accompanied by the hallmark cytokines for the respective Th subsets: TH1–IFN-γ, TH2–IL-4, and TH17–IL-17 (reviewed in ref. 39). IL-10 can also be produced by other immune cells such as CD8+ T cells, B cells, eosinophils, and mast cells; however, the pathways required for IL-10 induction in these cells are not fully known.

IL-10: REGULATION OF THE ANTIGEN-PRESENTING CELLS AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE PROTECTIVE TH1 RESPONSE

IL-10 inhibits the protective immune response to pathogens by blocking the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and the TH1-polarizing cytokine IL-12, by directly acting on antigen-presenting cells such as macrophages and DCs.65, 66 IL-10 can also inhibit phagocytosis and microbial killing through limiting the production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in response to IFN-γ,38, 67, 68 all of which are pivotal for mediating immunity to intracellular pathogens. Recent studies from several groups also suggest that the effects of IL-10 are not solely restricted to direct effects on the antigen-presenting cells as IL-10 can also enhance the differentiation of IL-10-producing inducible Tregs during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis.69 In addition, IL-10 from CD11b+ myeloid cells is also required for maintaining FoxP3 expression and Treg function,70 possibly via direct interactions through the IL-10-receptor (IL-10R) expressed on the Treg itself. These reports propose positive feedback loops for the induction of IL-10 by distinct Treg populations and thus provide an additional level of immune regulation. However, it is important to note that the direct effects of IL-10 on T cells remain unclear and further studies using T cell-specific deletion of the Il10ra gene will be necessary to definitively establish the significance of non-myeloid IL-10 signaling71 in regulation of the immune response.

IL-10 IN THE CONTEXT OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

The importance of IL-10 in controlling inflammatory responses was originally suggested by early observations in IL-10-deficient (Il10−/−) mice that develop unrelenting colitis72 in response to gut flora.73 In the context of infectious disease, studies using Listeria monocytogenes,74, 75, 76 lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus,77, 78 Leishmania major,79, 80 and Leishmania donovani81 have all reported an increase in pathogen clearance in the absence of IL-10, in addition to a range of other experimental infections.82 During L. major infection, although the absence of IL-10 enhanced pathogen clearance, mice displayed a loss of immunity to re-infection,80 suggesting that IL-10 does limit pathogen clearance, but has a key role in the maintenance of effector memory populations via a mechanism that remains unknown. In contrast, during infection with Toxoplasma gondii,83, 84, 85 Trypanosoma cruzi,86 and Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi,87 experimental infection in Il10−/− mice causes excessive and often lethal inflammatory responses. These studies, on Il10−/− mice during infection with diverse pathogens, highlight that IL-10 function may result in distinct outcomes during different infections. In some cases, too much IL-10 at one end of the scale may overcontrol otherwise protective T-cell responses, leading to chronic infection, and at the other end, too little or no IL-10 may tend toward fatal host-mediated pathology. Thus, IL-10 manages a delicate balance between suppressing and activating host responses to virtually all pathogens.

The initial innate immune response to Mtb: IL-10 regulation of macrophage and DC function

Upon aerosol exposure with Mtb, the first cells to be exposed to the pathogen include alveolar macrophages and lung DCs, both of which readily phagocytose Mtb and become activated, producing the cytokines TNF-α and IL-12 to promote host antimicrobial mechanisms, in addition to induction of IL-10, which may inhibit them.88, 89, 90, 91 Once phagocytosed by macrophages, the Mtb bacillus survives and persists by inhibition of phagosome–lysosome fusion,92 and in doing this Mtb can still gain access to essential nutrients such as iron via the early endocytic pathway.93, 94 The production of IL-10 following phagocytosis of Mtb by macrophages may occur as a natural antimicrobial response by the host, or may be induced by the bacteria as an evasion mechanism (discussed below). IL-10 blocks phagosome maturation by a STAT3-dependent, p38-independent mechanism, which facilitates Mtb survival and outgrowth.95 One key mechanism of Mtb killing is mediated by IFN-γ activation of macrophages, leading to enhanced production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates,96, 97, 98, 99 which can be inhibited by IL-10,38, 67, 68 and occurs by a MyD88-dependent mechanism.100 In addition to antagonizing the effects of IFN-γ on macrophage activation, IL-10 produced during phagocytosis may also function to block antigen presentation via downregulation of major histocompatibility complex molecules.38 DCs can be infected with Mtb,103, 104 but are unable to kill phagocytosed bacilli.90, 105 Instead, the primary function of DCs after mycobacterial infection is to process antigen and to migrate to draining lymph nodes. This process has in part been shown to be dependent on IL-12p40106 and can be inhibited by IL-10,106,107 inadvertently leading to disease progression. DCs drive T-cell differentiation,108, 109 and facilitate recruitment of Th1 cells back to the lung. Inhibitory effects of IL-10 on the production of C-X-C motif chemokine 10 (CXCL10; IFN-γ-induced protein 10 (IP-10)) during Mtb infection suggest that IL-10 may limit recruitment of TH1 cells to the lungs of infected mice110 (summarized in Figure 1). Indeed, the absence of DCs during early Mtb infection leads to an impaired TH1 response with increased bacterial loads.111

Evidence for IL-10 as a limiting factor in the immune response to Mtb in humans

In human TB studies, IL-10 has been shown to be elevated in the lungs112, 113, 114 and serum of active PTB patients.115 Studies on peripheral blood mononuclear cells obtained from PTB patients have shown that neutralization of endogenous IL-10 increased T-cell proliferation116 and IFN-γ production.116, 117 Furthermore, studies on peripheral blood mononuclear cells obtained from patients with anergic TB (individuals confirmed as having PTB but with no dermal reactivity to purified protein derivative (PPD)) have demonstrated that neutralization of endogenous IL-10 enhanced proliferative responses to PPD.118 Collectively, these studies117, 118 concluded that IL-10 was functioning to limit the immune response to Mtb and may contribute to TB pathogenesis. When looking specifically at lung samples from PTB patients, IL-10 and another immunosuppressive factor, TGF-β, were reported to be elevated in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, which comprised predominantly of macrophages and neutrophils.114, 119 A study by the same group also observed enhanced levels of IL-10 in the sputum of PTB patients, which positively correlated with the increased levels of CFP32, an Mtb antigen, suggesting an association between IL-10 and a failure to control Mtb infection.113 Interestingly, both IL-10 and TGF-β can inhibit CD4+ T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy PPD+ patients,120 most likely through inhibition of antigen-presenting cell function.

With these effects of IL-10 in mind, one potential source could be CD4+ T cells, as demonstrated by Gerosa et al.,121 who reported the presence of CD4+ T cells producing both IFN-γ and IL-10 in the Mtb antigen-specific T-cell clones isolated from BAL of active TB patients. These findings in the BAL were in contrast to CD4+ T cells derived from the peripheral blood.121 To compliment these conclusions in human BAL that CD4+ T cells are a source of IL-10 during infection, transgenic mice that overexpress IL-10 in the T-cell compartment have enhanced susceptibility to BCG101 and Mtb122 because of an inability to control infection leading to exacerbated disease. In keeping with a role for IL-10 in TB pathogenesis, in a human case–control study in The Gambia, variations in allele 2 of SLC11A1 (Nramp1) were identified along with an association with enhanced production of IL-10 by monocytes and innate cells in response to lipopolysaccharide. Such variations correlated with increased susceptibility to PTB.123 In line with these observations in human populations,123 infection of mice, where the macrophage compartment specifically overexpresses IL-10, leads to a significant reduction in reactive nitrogen intermediates, an increase in arginase-1, and overall reduced macrophage function.102 These findings are in keeping with recent studies showing that arginase-1 is specifically regulated by a STAT3-dependent pathway by autocrine/paracrine TLR-induced IL-10, IL-6, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor.124 These cytokines are found in abundance during mycobacterial infection and can collectively control arginase-1, and therefore nitric oxide amounts that would kill mycobacteria. Irrespective of the cellular source of IL-10 in studies using IL-10 transgenic mice, the outcome culminates in a pronounced inability to control bacterial growth, leading to mice succumbing earlier to disease during infection. These events occur despite the fact that the host has an intact T-cell IFN-γ response.101, 102 These studies highlight both innate and adaptive sources of IL-10 during Mtb infection, making it plausible that the cellular source of IL-10 is dynamic and is likely to depend on the stage of infection and anatomical location of the disease.

Human genetic studies examining the key polymorphisms in the IL-10 gene, more specifically loci 1,082, 819, and 592, and susceptibility to TB, have proved inconclusive with mixed outcomes that appear to be dependent on geographical location.125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134 Furthermore, using meta-analysis, Pacheco et al.135 analyzed the IL-10 polymorphism data from published studies125, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133 and showed a trend toward an association between polymorphisms in the IL-10 gene and increased susceptibility; however, it did not reach statistical significance.135 In conclusion, the human studies of TB infection suggest that during chronic infection, endogenous IL-10 from both innate and adaptive sources may inhibit protective TH1 responses via indirect action on macrophages or DCs, and although functioning to limit immunopathology may result in chronic infection. However, these studies could not address the relationship between IL-10 and its suppressive effect on pathogen eradication.

THE ROLE OF IL-10 IN LIMITING THE IMMUNE RESPONSE IN MOUSE MODELS OF NONTUBERCULAR MYCOBACTERIAL INFECTIONS

Studies addressing the role of IL-10 during mycobacterial infections such as Mycobacterium avium136, 137, 138 and BCG139, 140, 141 in Il10−/− mice show enhanced protection while showing no signs of aberrant host-mediated pathology, which perhaps reflects the slow disease progression of these mycobacterial pathogens. Furthermore, in the context of infectious disease, antagonists of IL-10 may act as adjuvants during vaccination as has been shown with L. major142, 143, 144 or M. avium,145 which significantly improves disease outcome (reviewed in ref. 146).

THE ROLE OF IL-10 IN LIMITING THE IMMUNE RESPONSE IN MOUSE MODELS OF Mtb INFECTION

Human TB studies suggest a potential role for IL-10 in TB pathogenesis; however, specific aspects of TB biology, for example bacterial killing, cannot be readily addressed in vivo in humans. Experimental animal models, such as the mouse, represent a reproducible in vivo manipulative system and serve as a crucial aid, allowing us to bridge these limitations and to gain further insight into complex human diseases like TB. Initially, the role of IL-10 during murine Mtb infection appeared controversial, with studies focusing predominantly on Il10−/− mice on the so-called “resistant” genetic backgrounds such as the C57Bl/6. Some groups have reported that Il10−/− mice have comparable lung bacterial loads following aerosol Mtb infection when compared with wild-type mice.147, 148, 149 Interestingly, the levels of IFN-γ observed in the lungs of Il10−/− mice from these studies were greatly enhanced early during infection when compared with wild-type mice, although in these studies this failed to translate into any effect on bacterial control.147, 149 One study went on to suggest that the lack of effect on bacterial load in C57BL/6 Il10−/− mice was in fact because of compensatory immune suppression by TGF-β,149, 150 and that Il10−/− animals succumbed earlier than wild-type controls during chronic stages of infection because of host-mediated pathology.149

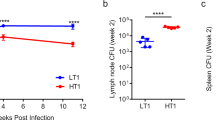

In contrast, others have reported that in the absence of IL-10, mice display enhanced resistance to aerosol Mtb infection with reduced bacterial loads.110, 137, 151 Accompanying this decrease in bacterial load were elevated production of IFN-γ137, 152 and earlier enhanced levels of cytokines associated with granuloma formation (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, TNF-α, and IL-17A), and T-cell recruitment (CXCL10 and IL-17A) in the lungs and serum.110 In line with the human polymorphism studies, which highlight genetic variability in the Il10 locus between different geographic populations and increased susceptibility to TB, similar findings have been observed between genetically different strains of mice. Mtb infection in “susceptible” mouse strains such as the CBA/J, which has a greater propensity to produce IL-10 relative to other inbred mouse strains, leads to decreased IL-12p40, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, and exacerbated bacterial burdens.122 These observations are in contrast to “resistant” C57Bl/6 mice, which produce lower amounts relative to other strains.122 To counteract the enhanced levels of IL-10 in CBA/J mice, blockade of IL-10R signaling during chronic infection with an IL-10R blocking monoclonal antibody (anti-IL-10R) enhances T-cell recruitment and T cell-derived IFN-γ, leading to enhanced survival associated with reduced bacterial burdens.151 Furthermore, our group has also recently shown that Mtb infection of Il10−/− mice on both the C57Bl/6 and BALB/c backgrounds, as well as in CBA/J mice treated throughout infection with anti-IL-10R monoclonal antibody, leads to increased reductions in bacterial load in both the lungs and spleen when compared with their respective control counterparts.110 The differences between these studies may be linked to the sources of mice, their biological-specific pathogen-free status, including gut flora, or differences between laboratory strains of Mtb used.153 These factors may translate into phenotypic differences during controlled experimental infections.

IMMUNE SUBVERSION BY Mtb THROUGH INDUCTION OF IL-10

The induction of IL-10 during Mtb infection may not just be a response initiated by the host in order to avoid or limit host-mediated pathologies. Evidence from viral infections such as Epstein–Barr virus suggest that during infection IL-10 can indeed be induced to blunt the immune response and allow the establishment of a chronic infection (reviewed in ref. 38). Similar to viruses, these observations have also been noted during Mtb infection. Two such examples include the Mtb strains “HN878” and “CH.” The Mtb strain HN878, a member of the W-Beijing lineage, was originally isolated in Houston (USA) after causing 60 cases of TB and was responsible for at least three clusters of disease between 1995 and 1998. HN878 has a hypervirulent phenotype in mice,154 which is associated with the presence of a phenolic glycolipid,155 normally absent in other clinical Mtb isolates (CDC1551) or laboratory strains (H37Rv). Furthermore, the hypervirulent phenotype of HN878 has been strongly associated with the induction of type I IFNs154, 156 as well as the early induction of IL-10 by a CD4+CD25+FoxP3+CD223+ regulatory T-cell population,157 and enhanced arginase-1 expression.124 The Mtb strain CH was originally isolated in 2001 following a school-associated outbreak in Leicester (UK) and its virulence was associated with a deletion affecting the Mtb gene Rv1519.158 Infection of human monocyte-derived macrophages with the CH strain (when compared with the well-documented Mtb strains CDC1551 and H37Rv) led to induction of IL-10, which correlated with reduced production of IL-12p40. Complementation of the CH strain with Rv1519 reversed this capacity to specifically induce IL-10. These studies clearly demonstrate another virulence mechanism whereby Mtb can exploit host-derived factors in order to establish chronic infection through subversion of the protective host response, a mechanism that, to date, warrants further investigation.

CONCLUDING REMARKS AND FUTURE ISSUES

We hypothesize that IL-10 is functioning largely to limit pathogen clearance during the early immune response to Mtb by its inhibitory effects on macrophage activation and DC function. One such pathway includes the inhibition of phagosome–lysosome fusion.95 The induction of IL-10 may differ between Mtb isolates, and the cellular source of IL-10 during infection appears to be dynamic, probably depending on the stage of infection, the anatomical location of the disease and the specific pathogen. For example, the early sources of IL-10 during infection are myeloid cells such as macrophages. However, as the adaptive cell-mediated response becomes apparent, the T cells become a major source of IL-10 production. To date, there is limited information on the specific cellular sources of IL-10 during the course of Mtb infection, an area that we feel warrants further investigation. Identifying the cellular sources of IL-10 following vaccination, and in response to Mtb infection, may provide us with immunotherapeutic targets in order to fight TB. Once chronic infection has been established and levels of IL-10 are still detectable, it would seem plausible to suggest that IL-10 now serves to limit fatal host-mediated immunopathology by blunting overexuberant effector responses. In this context, it would appear that successful mycobacterial strains have harnessed the natural suppressive effects of IL-10 to create a niche within nonoptimally activated macrophages. In this scenario, the host also benefits by escaping damaging immunopathology. However, to date, there is limited published evidence supporting a role for IL-10 in blocking host-mediated immunopathology during chronic Mtb infection.149 In contrast to Higgins et al.,149 our own group have found no signs of lung immunopathology (including weight loss) in Il10−/− mice during Mtb infection (P.S. Redford and A. O’Garra, unpublished data) despite observations that Il10−/− mice have significantly enhanced levels of IFN-γ and IL-17 early during infection.110 In the context of IL-17-driven immunopathology, the balance between IFN-γ and IL-17 production during the course of Mtb infection is likely to be a key determinant in the immunopathological outcome (reviewed in ref. 159). Potentially, if the balance shifts in favor of IL-17, this may facilitate host-mediated pathology by the recruitment of neutrophils that may potentially hamper protective immune responses as observed in susceptible mouse strains that exhibit enhanced lung neutrophila and high mortality160, 161 or in Mtb-infected mice given repeated BCG vaccination.162 With the potential for IL-17 to drive protective immune responses as well as contribute to immunopathology, its regulation by IFN-γ and/or IL-10 during Mtb infection has received limited attention to date. However, one study from our group has shown that IL-10 may dampen IL-17A production during Mtb infection.110 Furthermore, the increased IL-17A observed in Il10−/− mice was not responsible for the enhanced cellular responses or the enhanced protection observed110 and did not lead to immunopathology.

In contrast, the role of IL-17 in bacterial control during primary immune responses to Mtb is less clear, yielding conflicting reports.110, 163, 164, 165

The induction of IL-10 during vaccination or chemotherapy could skew the priming or clearance of Mtb and in its absence may yield a better prognosis for the host, and may provide a strategy to help eliminate infection with multidrug-resistant Mtb. For example, during vaccination leading to enhanced protection to subsequent Mtb infection, IL-23 facilitates the recruitment of IL-17-producing antigen-specific cells into the lungs, which in turn drives the influx of TH1 cells166 (reviewed in ref. 167). IL-10 could be functioning to regulate the sources of IL-23 during the early stages of vaccination or in response to Mtb challenge. Future strategies for combating TB should therefore look toward the role of IL-10 in these scenarios and how in the absence of IL-10 the immune response is changed, as has been shown in models of Leishmania,142, 143, 144 M. avium,145 and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus78 (reviewed in ref. 146).

In summary, the protective immune response to Mtb infection, which prevents progression to active disease, may be attributed to the finite balance between proinflammatory and immunoregulatory mechanisms. IL-10 represents one such regulatory mechanism that Mtb could be exploiting in order to establish a chronic infection and may therefore serve as an important target for the design of novel immune therapies.

References

WHO. World Health Organisation: Global Tuberculosis Control 2010 http://www.who.int/tb/country/en/index.html (2010).

Flynn, J.L. & Chan, J. What's good for the host is good for the bug. Trends Microbiol. 13, 98–102 (2005).

Ulrichs, T. & Kaufmann, S.H. New insights into the function of granulomas in human tuberculosis. J. Pathol. 208, 261–269 (2006).

Davis, J.M. & Ramakrishnan, L. The role of the granuloma in expansion and dissemination of early tuberculous infection. Cell 136, 37–49 (2009).

Volkman, H.E., Pozos, T.C., Zheng, J., Davis, J.M., Rawls, J.F. & Ramakrishnan, L. Tuberculous granuloma induction via interaction of a bacterial secreted protein with host epithelium. Science 327, 466–469 (2010).

Tobin, D.M. & Ramakrishnan, L. Comparative pathogenesis of Mycobacterium marinum and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Microbiol. 10, 1027–1039 (2008).

Zhang, S.Y. et al. Inborn errors of interferon (IFN)-mediated immunity in humans: insights into the respective roles of IFN-alpha/beta, IFN-gamma, and IFN-lambda in host defense. Immunol. Rev. 226, 29–40 (2008).

Altare, F. et al. Impairment of mycobacterial immunity in human interleukin-12 receptor deficiency. Science 280, 1432–1435 (1998).

Casanova, J.L. & Abel, L. Genetic dissection of immunity to mycobacteria: the human model. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20, 581–620 (2002).

Dorman, S.E. & Holland, S.M. Interferon-gamma and interleukin-12 pathway defects and human disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 11, 321–333 (2000).

Remus, N. et al. Association of IL12RB1 polymorphisms with pulmonary tuberculosis in adults in Morocco. J. Infect. Dis. 190, 580–587 (2004).

Newport, M.J., Awomoyi, A.A. & Blackwell, J.M. Polymorphism in the interferon-gamma receptor-1 gene and susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis in The Gambia. Scand. J. Immunol. 58, 383–385 (2003).

Jouanguy, E. et al. Partial interferon-gamma receptor 1 deficiency in a child with tuberculoid bacillus Calmette-Guerin infection and a sibling with clinical tuberculosis. J. Clin. Invest. 100, 2658–2664 (1997).

Jouanguy, E. et al. A human IFNGR1 small deletion hotspot associated with dominant susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. Nat. Genet. 21, 370–378 (1999).

Dorman, S.E. & Holland, S.M. Mutation in the signal-transducing chain of the interferon-gamma receptor and susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 2364–2369 (1998).

Dupuis, S. et al. Impairment of mycobacterial but not viral immunity by a germline human STAT1 mutation. Science 293, 300–303 (2001).

Holland, S.M. Interferon gamma, IL-12, IL-12R and STAT-1 immunodeficiency diseases: disorders of the interface of innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol. Res. 38, 342–346 (2007).

Dorman, S.E. et al. Clinical features of dominant and recessive interferon gamma receptor 1 deficiencies. Lancet 364, 2113–2121 (2004).

Selwyn, P.A. et al. A prospective study of the risk of tuberculosis among intravenous drug users with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 320, 545–550 (1989).

Post, F.A., Wood, R. & Pillay, G.P. Pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV infection: radiographic appearance is related to CD4+ T-lymphocyte count. Tuber. Lung Dis. 76, 518–521 (1995).

Nunn, P., Williams, B., Floyd, K., Dye, C., Elzinga, G. & Raviglione, M. Tuberculosis control in the era of HIV. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 819–826 (2005).

Diedrich, C.R. et al. Reactivation of latent tuberculosis in cynomolgus macaques infected with SIV is associated with early peripheral T cell depletion and not virus load. PLoS One 5, e9611 (2010).

Caruso, A.M., Serbina, N., Klein, E., Triebold, K., Bloom, B.R. & Flynn, J.L. Mice deficient in CD4T cells have only transiently diminished levels of IFN-gamma, yet succumb to tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 162, 5407–5416 (1999).

Mogues, T., Goodrich, M.E., Ryan, L., LaCourse, R. & North, R.J. The relative importance of T cell subsets in immunity and immunopathology of airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. J. Exp. Med. 193, 271–280 (2001).

Scanga, C.A. et al. Depletion of CD4(+) T cells causes reactivation of murine persistent tuberculosis despite continued expression of interferon gamma and nitric oxide synthase 2. J. Exp. Med. 192, 347–358 (2000).

Keane, J. et al. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 1098–1104 (2001).

Lin, P.L. et al. Tumor necrosis factor neutralization results in disseminated disease in acute and latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection with normal granuloma structure in a cynomolgus macaque model. Arthritis Rheum. 62, 340–350 (2010).

Mohan, V.P. et al. Effects of tumor necrosis factor alpha on host immune response in chronic persistent tuberculosis: possible role for limiting pathology. Infect. Immun. 69, 1847–1855 (2001).

Scanga, C.A., Mohan, V.P., Joseph, H., Yu, K., Chan, J. & Flynn, J.L. Reactivation of latent tuberculosis: variations on the Cornell murine model. Infect. Immun. 67, 4531–4538 (1999).

Cooper, A.M., Dalton, D.K., Stewart, T.A., Griffin, J.P., Russell, D.G. & Orme, I.M. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice. J. Exp. Med. 178, 2243–2247 (1993).

Flynn, J.L., Chan, J., Triebold, K.J., Dalton, D.K., Stewart, T.A. & Bloom, B.R. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 178, 2249–2254 (1993).

Cooper, A.M., Magram, J., Ferrante, J. & Orme, I.M. Interleukin 12 (IL-12) is crucial to the development of protective immunity in mice intravenously infected with mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 186, 39–45 (1997).

Cooper, A.M., Roberts, A.D., Rhoades, E.R., Callahan, J.E., Getzy, D.M. & Orme, I.M. The role of interleukin-12 in acquired immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Immunology 84, 423–432 (1995).

Flynn, J.L., Goldstein, M.M., Triebold, K.J., Sypek, J., Wolf, S. & Bloom, B.R. IL-12 increases resistance of BALB/c mice to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Immunol. 155, 2515–2524 (1995).

Bean, A.G. et al. Structural deficiencies in granuloma formation in TNF gene-targeted mice underlie the heightened susceptibility to aerosol Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, which is not compensated for by lymphotoxin. J. Immunol. 162, 3504–3511 (1999).

Flynn, J.L. et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is required in the protective immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Immunity 2, 561–572 (1995).

Fiorentino, D.F., Bond, M.W. & Mosmann, T.R. Two types of mouse T helper cell. IV. Th2 clones secrete a factor that inhibits cytokine production by Th1 clones. J. Exp. Med. 170, 2081–2095 (1989).

Moore, K.W., de Waal Malefyt, R., Coffman, R.L. & O'Garra, A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19, 683–765 (2001).

Saraiva, M. & O'Garra, A. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 170–181 (2010).

O'Garra, A., Vieira, P.L., Vieira, P. & Goldfeld, A.E. IL-10-producing and naturally occurring CD4+ Tregs: limiting collateral damage. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 1372–1378 (2004).

Belkaid, Y. & Chen, W. Regulatory ripples. Nat. Immunol. 11, 1077–1078 (2010).

Barnes, M.J. & Powrie, F. Regulatory T cells reinforce intestinal homeostasis. Immunity 31, 401–411 (2009).

Scott-Browne, J.P. et al. Expansion and function of Foxp3-expressing T regulatory cells during tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 204, 2159–2169 (2007).

Shafiani, S., Tucker-Heard, G., Kariyone, A., Takatsu, K. & Urdahl, K.B. Pathogen-specific regulatory T cells delay the arrival of effector T cells in the lung during early tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 207, 1409–1420 (2010).

Anderson, C.F., Oukka, M., Kuchroo, V.J. & Sacks, D. CD4(+)CD25(−)Foxp3(−) Th1 cells are the source of IL-10-mediated immune suppression in chronic cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Exp. Med. 204, 285–297 (2007).

Jankovic, D. et al. Conventional T-bet(+)Foxp3(−) Th1 cells are the major source of host-protective regulatory IL-10 during intracellular protozoan infection. J. Exp. Med. 204, 273–283 (2007).

Williams, L., Bradley, L., Smith, A. & Foxwell, B. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 is the dominant mediator of the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10 in human macrophages. J. Immunol. 172, 567–576 (2004).

El Kasmi, K.C. et al. General nature of the STAT3-activated anti-inflammatory response. J. Immunol. 177, 7880–7888 (2006).

Holland, S.M. et al. STAT3 mutations in the hyper-IgE syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 1608–1619 (2007).

Kaiser, F. et al. TPL-2 negatively regulates interferon-beta production in macrophages and myeloid dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 206, 1863–1871 (2009).

Boonstra, A. et al. Macrophages and myeloid dendritic cells, but not plasmacytoid dendritic cells, produce IL-10 in response to MyD88- and TRIF-dependent TLR signals, and TLR-independent signals. J. Immunol. 177, 7551–7558 (2006).

Chang, E.Y., Guo, B., Doyle, S.E. & Cheng, G. Cutting edge: involvement of the type I IFN production and signaling pathway in lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-10 production. J. Immunol. 178, 6705–6709 (2007).

Iyer, S.S., Ghaffari, A.A. & Cheng, G. Lipopolysaccharide-mediated IL-10 transcriptional regulation requires sequential induction of type I IFNs and IL-27 in macrophages. J. Immunol. 185, 6599–6607 (2010).

Fremond, C.M., Yeremeev, V., Nicolle, D.M., Jacobs, M., Quesniaux, V.F. & Ryffel, B. Fatal Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection despite adaptive immune response in the absence of MyD88. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 1790–1799 (2004).

Scanga, C.A., Bafica, A., Feng, C.G., Cheever, A.W., Hieny, S. & Sher, A. MyD88-deficient mice display a profound loss in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis associated with partially impaired Th1 cytokine and nitric oxide synthase 2 expression. Infect. Immun. 72, 2400–2404 (2004).

Reiling, N., Ehlers, S. & Holscher, C. MyDths and un-TOLLed truths: sensor, instructive and effector immunity to tuberculosis. Immunol. Lett. 116, 15–23 (2008).

Mayer-Barber, K.D. et al. Caspase-1 independent IL-1beta production is critical for host resistance to mycobacterium tuberculosis and does not require TLR signaling in vivo. J. Immunol. 184, 3326–3330 (2010).

Rogers, N.C. et al. Syk-dependent cytokine induction by Dectin-1 reveals a novel pattern recognition pathway for C type lectins. Immunity 22, 507–517 (2005).

Dorhoi, A. et al. The adaptor molecule CARD9 is essential for tuberculosis control. J. Exp. Med. 207, 777–792 (2010).

Zhang, X., Majlessi, L., Deriaud, E., Leclerc, C. & Lo-Man, R. Coactivation of syk kinase and MyD88 adaptor protein pathways by bacteria promotes regulatory properties of neutrophils. Immunity 31, 761–771 (2009).

Geijtenbeek, T.B. et al. Mycobacteria target DC-SIGN to suppress dendritic cell function. J. Exp. Med. 197, 7–17 (2003).

Gerber, J.S. & Mosser, D.M. Reversing lipopolysaccharide toxicity by ligating the macrophage Fc gamma receptors. J. Immunol. 166, 6861–6868 (2001).

Edwards, A.D. et al. Microbial recognition via Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent pathways determines the cytokine response of murine dendritic cell subsets to CD40 triggering. J. Immunol. 169, 3652–3660 (2002).

Saraiva, M., Christensen, J.R., Veldhoen, M., Murphy, T.L., Murphy, K.M. & O'Garra, A. Interleukin-10 production by Th1 cells requires interleukin-12-induced STAT4 transcription factor and ERK MAP kinase activation by high antigen dose. Immunity 31, 209–219 (2009).

Fiorentino, D.F., Zlotnik, A., Mosmann, T.R., Howard, M. & O'Garra, A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J. Immunol. 147, 3815–3822 (1991).

Fiorentino, D.F. et al. IL-10 acts on the antigen-presenting cell to inhibit cytokine production by Th1 cells. J. Immunol. 146, 3444–3451 (1991).

Gazzinelli, R.T., Oswald, I.P., James, S.L. & Sher, A. IL-10 inhibits parasite killing and nitrogen oxide production by IFN-gamma-activated macrophages. J. Immunol. 148, 1792–1796 (1992).

Redpath, S., Ghazal, P. & Gascoigne, N.R. Hijacking and exploitation of IL-10 by intracellular pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 9, 86–92 (2001).

Barrat, F.J. et al. In vitro generation of interleukin 10-producing regulatory CD4(+) T cells is induced by immunosuppressive drugs and inhibited by T helper type 1 (Th1)- and Th2-inducing cytokines. J. Exp. Med. 195, 603–616 (2002).

Murai, M. et al. Interleukin 10 acts on regulatory T cells to maintain expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 and suppressive function in mice with colitis. Nat. Immunol. 10, 1178–1184 (2009).

Pils, M.C. et al. Monocytes/macrophages and/or neutrophils are the target of IL-10 in the LPS endotoxemia model. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 443–448 (2010).

Kuhn, R., Lohler, J., Rennick, D., Rajewsky, K. & Muller, W. Interleukin-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell 75, 263–274 (1993).

Sellon, R.K. et al. Resident enteric bacteria are necessary for development of spontaneous colitis and immune system activation in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Infect. Immun. 66, 5224–5231 (1998).

Dai, W.J., Kohler, G. & Brombacher, F. Both innate and acquired immunity to Listeria monocytogenes infection are increased in IL-10-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 158, 2259–2267 (1997).

Silva, R.A. & Appelberg, R. Blocking the receptor for interleukin 10 protects mice from lethal listeriosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 1312–1314 (2001).

Wagner, R.D., Maroushek, N.M., Brown, J.F. & Czuprynski, C.J. Treatment with anti-interleukin-10 monoclonal antibody enhances early resistance to but impairs complete clearance of Listeria monocytogenes infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 62, 2345–2353 (1994).

Brooks, D.G., Trifilo, M.J., Edelmann, K.H., Teyton, L., McGavern, D.B. & Oldstone, M.B. Interleukin-10 determines viral clearance or persistence in vivo. Nat. Med. 12, 1301–1309 (2006).

Brooks, D.G., Lee, A.M., Elsaesser, H., McGavern, D.B. & Oldstone, M.B. IL-10 blockade facilitates DNA vaccine-induced T cell responses and enhances clearance of persistent virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 205, 533–541 (2008).

Belkaid, Y. et al. The role of interleukin (IL)-10 in the persistence of Leishmania major in the skin after healing and the therapeutic potential of anti-IL-10 receptor antibody for sterile cure. J. Exp. Med. 194, 1497–1506 (2001).

Belkaid, Y., Piccirillo, C.A., Mendez, S., Shevach, E.M. & Sacks, D.L. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control Leishmania major persistence and immunity. Nature 420, 502–507 (2002).

Murray, H.W. et al. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) in experimental visceral leishmaniasis and IL-10 receptor blockade as immunotherapy. Infect. Immun. 70, 6284–6293 (2002).

Mege, J.L., Meghari, S., Honstettre, A., Capo, C. & Raoult, D. The two faces of interleukin 10 in human infectious diseases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6, 557–569 (2006).

Gazzinelli, R.T. et al. In the absence of endogenous IL-10, mice acutely infected with Toxoplasma gondii succumb to a lethal immune response dependent on CD4+ T cells and accompanied by overproduction of IL-12, IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha. J. Immunol. 157, 798–805 (1996).

Reis e Sousa, C. et al. Paralysis of dendritic cell IL-12 production by microbial products prevents infection-induced immunopathology. Immunity 11, 637–647 (1999).

Suzuki, Y. et al. IL-10 is required for prevention of necrosis in the small intestine and mortality in both genetically resistant BALB/c and susceptible C57BL/6 mice following peroral infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 164, 5375–5382 (2000).

Hunter, C.A. et al. IL-10 is required to prevent immune hyperactivity during infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Immunol. 158, 3311–3316 (1997).

Li, C., Corraliza, I. & Langhorne, J. A defect in interleukin-10 leads to enhanced malarial disease in Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 67, 4435–4442 (1999).

Shaw, T.C., Thomas, L.H. & Friedland, J.S. Regulation of IL-10 secretion after phagocytosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by human monocytic cells. Cytokine 12, 483–486 (2000).

Giacomini, E. et al. Infection of human macrophages and dendritic cells with Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces a differential cytokine gene expression that modulates T cell response. J. Immunol. 166, 7033–7041 (2001).

Bodnar, K.A., Serbina, N.V. & Flynn, J.L. Fate of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within murine dendritic cells. Infect. Immun. 69, 800–809 (2001).

Hickman, S.P., Chan, J. & Salgame, P. Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces differential cytokine production from dendritic cells and macrophages with divergent effects on naive T cell polarization. J. Immunol. 168, 4636–4642 (2002).

Armstrong, J.A. & Hart, P.D. Response of cultured macrophages to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with observations on fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes. J. Exp. Med. 134, 713–740 (1971).

Sturgill-Koszycki, S., Schaible, U.E. & Russell, D.G. Mycobacterium-containing phagosomes are accessible to early endosomes and reflect a transitional state in normal phagosome biogenesis. EMBO J. 15, 6960–6968 (1996).

Collins, H.L., Kaufmann, S.H. & Schaible, U.E. Iron chelation via deferoxamine exacerbates experimental salmonellosis via inhibition of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase-dependent respiratory burst. J. Immunol. 168, 3458–3463 (2002).

O'Leary, S., O'Sullivan, M.P. & Keane, J. IL-10 blocks phagosome maturation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected human macrophages. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. doi:10.1165/rcmb.2010-0319OC (2010).

Chan, J., Tanaka, K., Carroll, D., Flynn, J. & Bloom, B.R. Effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors on murine infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 63, 736–740 (1995).

Chan, J., Xing, Y., Magliozzo, R.S. & Bloom, B.R. Killing of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis by reactive nitrogen intermediates produced by activated murine macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 175, 1111–1122 (1992).

Flynn, J.L., Scanga, C.A., Tanaka, K.E. & Chan, J. Effects of aminoguanidine on latent murine tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 160, 1796–1803 (1998).

MacMicking, J.D., North, R.J., LaCourse, R., Mudgett, J.S., Shah, S.K. & Nathan, C.F. Identification of nitric oxide synthase as a protective locus against tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 5243–5248 (1997).

Shi, S. et al. MyD88 primes macrophages for full-scale activation by interferon-gamma yet mediates few responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 198, 987–997 (2003).

Murray, P.J., Wang, L., Onufryk, C., Tepper, R.I. & Young, R.A. T cell-derived IL-10 antagonizes macrophage function in mycobacterial infection. J. Immunol. 158, 315–321 (1997).

Schreiber, T. et al. Autocrine IL-10 induces hallmarks of alternative activation in macrophages and suppresses antituberculosis effector mechanisms without compromising T cell immunity. J. Immunol. 183, 1301–1312 (2009).

Garcia-Romo, G.S. et al. Airways infection with virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis delays the influx of dendritic cells and the expression of costimulatory molecules in mediastinal lymph nodes. Immunology 112, 661–668 (2004).

Wolf, A.J. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infects dendritic cells with high frequency and impairs their function in vivo. J. Immunol. 179, 2509–2519 (2007).

Tailleux, L. et al. Constrained intracellular survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 170, 1939–1948 (2003).

Khader, S.A. et al. Interleukin 12p40 is required for dendritic cell migration and T cell priming after Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 203, 1805–1815 (2006).

Demangel, C., Bertolino, P. & Britton, W.J. Autocrine IL-10 impairs dendritic cell (DC)-derived immune responses to mycobacterial infection by suppressing DC trafficking to draining lymph nodes and local IL-12 production. Eur. J. Immunol. 32, 994–1002 (2002).

Reiley, W.W. et al. ESAT-6-specific CD4T cell responses to aerosol Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection are initiated in the mediastinal lymph nodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 10961–10966 (2008).

Wolf, A.J. et al. Initiation of the adaptive immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis depends on antigen production in the local lymph node, not the lungs. J. Exp. Med. 205, 105–115 (2008).

Redford, P.S. et al. Enhanced protection to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in IL-10-deficient mice is accompanied by early and enhanced Th1 responses in the lung. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 2200–2210 (2010).

Tian, T., Woodworth, J., Skold, M. & Behar, S.M. In vivo depletion of CD11c+ cells delays the CD4+ T cell response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and exacerbates the outcome of infection. J. Immunol. 175, 3268–3272 (2005).

Barnes, P.F., Lu, S., Abrams, J.S., Wang, E., Yamamura, M. & Modlin, R.L. Cytokine production at the site of disease in human tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 61, 3482–3489 (1993).

Huard, R.C. et al. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex-restricted gene cfp32 encodes an expressed protein that is detectable in tuberculosis patients and is positively correlated with pulmonary interleukin-10. Infect. Immun. 71, 6871–6883 (2003).

Almeida, A.S. et al. Tuberculosis is associated with a down-modulatory lung immune response that impairs Th1-type immunity. J. Immunol. 183, 718–731 (2009).

Verbon, A., Juffermans, N., Van Deventer, S.J., Speelman, P., Van Deutekom, H. & Van Der Poll, T. Serum concentrations of cytokines in patients with active tuberculosis (TB) and after treatment. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 115, 110–113 (1999).

Zhang, M., Gong, J., Iyer, D.V., Jones, B.E., Modlin, R.L. & Barnes, P.F. T cell cytokine responses in persons with tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Clin. Invest. 94, 2435–2442 (1994).

Gong, J.H. et al. Interleukin-10 downregulates Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced Th1 responses and CTLA-4 expression. Infect. Immun. 64, 913–918 (1996).

Boussiotis, V.A. et al. IL-10-producing T cells suppress immune responses in anergic tuberculosis patients. J. Clin. Invest. 105, 1317–1325 (2000).

Bonecini-Almeida, M.G. et al. Down-modulation of lung immune responses by interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) and analysis of TGF-beta receptors I and II in active tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 72, 2628–2634 (2004).

Rojas, R.E., Balaji, K.N., Subramanian, A. & Boom, W.H. Regulation of human CD4(+) alphabeta T-cell-receptor-positive (TCR(+)) and gammadelta TCR(+) T-cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis by interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor beta. Infect. Immun. 67, 6461–6472 (1999).

Gerosa, F. et al. CD4(+) T cell clones producing both interferon-gamma and interleukin-10 predominate in bronchoalveolar lavages of active pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Clin. Immunol. 92, 224–234 (1999).

Turner, J. et al. In vivo IL-10 production reactivates chronic pulmonary tuberculosis in C57BL/6 mice. J. Immunol. 169, 6343–6351 (2002).

Awomoyi, A.A., Marchant, A., Howson, J.M., McAdam, K.P., Blackwell, J.M. & Newport, M.J. Interleukin-10, polymorphism in SLC11A1 (formerly NRAMP1), and susceptibility to tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 186, 1808–1814 (2002).

Qualls, J.E. et al. Arginine usage in mycobacteria-infected macrophages depends on autocrine-paracrine cytokine signaling. Sci. Signal. 3, ra62 (2010).

Bellamy, R., Ruwende, C., Corrah, T., McAdam, K.P., Whittle, H.C. & Hill, A.V. Assessment of the interleukin 1 gene cluster and other candidate gene polymorphisms in host susceptibility to tuberculosis. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79, 83–89 (1998).

Delgado, J.C., Baena, A., Thim, S. & Goldfeld, A.E. Ethnic-specific genetic associations with pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 186, 1463–1468 (2002).

Lopez-Maderuelo, D. et al. Interferon-gamma and interleukin-10 gene polymorphisms in pulmonary tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 167, 970–975 (2003).

Fitness, J. et al. Large-scale candidate gene study of tuberculosis susceptibility in the Karonga district of northern Malawi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 71, 341–349 (2004).

Shin, H.D., Park, B.L., Kim, Y.H., Cheong, H.S., Lee, I.H. & Park, S.K. Common interleukin 10 polymorphism associated with decreased risk of tuberculosis. Exp. Mol. Med. 37, 128–132 (2005).

Henao, M.I., Montes, C., Paris, S.C. & Garcia, L.F. Cytokine gene polymorphisms in Colombian patients with different clinical presentations of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 86, 11–19 (2006).

Oral, H.B. et al. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) gene polymorphism as a potential host susceptibility factor in tuberculosis. Cytokine 35, 143–147 (2006).

Oh, J.H. et al. Polymorphisms of interleukin-10 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha genes are associated with newly diagnosed and recurrent pulmonary tuberculosis. Respirology 12, 594–598 (2007).

Prabhu Anand, S., Selvaraj, P., Jawahar, M.S., Adhilakshmi, A.R. & Narayanan, P.R. Interleukin-12B & interleukin-10 gene polymorphisms in pulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J. Med. Res. 126, 135–138 (2007).

Ates, O., Musellim, B., Ongen, G. & Topal-Sarikaya, A. Interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphisms in tuberculosis. J. Clin. Immunol. 28, 232–236 (2008).

Pacheco, A.G., Cardoso, C.C. & Moraes, M.O. IFNG +874T/A, IL10 -1082G/A and TNF -308G/A polymorphisms in association with tuberculosis susceptibility: a meta-analysis study. Hum. Genet. 123, 477–484 (2008).

Bermudez, L.E. & Champsi, J. Infection with Mycobacterium avium induces production of interleukin-10 (IL-10), and administration of anti-IL-10 antibody is associated with enhanced resistance to infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 61, 3093–3097 (1993).

Roach, D.R., Martin, E., Bean, A.G., Rennick, D.M., Briscoe, H. & Britton, W.J. Endogenous inhibition of antimycobacterial immunity by IL-10 varies between mycobacterial species. Scand. J. Immunol. 54, 163–170 (2001).

Roque, S., Nobrega, C., Appelberg, R. & Correia-Neves, M. IL-10 underlies distinct susceptibility of BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice to Mycobacterium avium infection and influences efficacy of antibiotic therapy. J. Immunol. 178, 8028–8035 (2007).

Murray, P.J. & Young, R.A. Increased antimycobacterial immunity in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Infect. Immun. 67, 3087–3095 (1999).

Jacobs, M., Brown, N., Allie, N., Gulert, R. & Ryffel, B. Increased resistance to mycobacterial infection in the absence of interleukin-10. Immunology 100, 494–501 (2000).

Jacobs, M., Fick, L., Allie, N., Brown, N. & Ryffel, B. Enhanced immune response in Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette Guerin (BCG)-infected IL-10-deficient mice. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 40, 893–902 (2002).

Roberts, M.T., Stober, C.B., McKenzie, A.N. & Blackwell, J.M. Interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-10 collude in vaccine failure for novel exacerbatory antigens in murine Leishmania major infection. Infect. Immun. 73, 7620–7628 (2005).

Stober, C.B., Lange, U.G., Roberts, M.T., Alcami, A. & Blackwell, J.M. IL-10 from regulatory T cells determines vaccine efficacy in murine Leishmania major infection. J. Immunol. 175, 2517–2524 (2005).

Tabbara, K.S. et al. Conditions influencing the efficacy of vaccination with live organisms against Leishmania major infection. Infect. Immun. 73, 4714–4722 (2005).

Silva, R.A., Pais, T.F. & Appelberg, R. Blocking the receptor for IL-10 improves antimycobacterial chemotherapy and vaccination. J. Immunol. 167, 1535–1541 (2001).

O'Garra, A., Barrat, F.J., Castro, A.G., Vicari, A. & Hawrylowicz, C. Strategies for use of IL-10 or its antagonists in human disease. Immunol. Rev. 223, 114–131 (2008).

Jung, Y.J., Ryan, L., LaCourse, R. & North, R.J. Increased interleukin-10 expression is not responsible for failure of T helper 1 immunity to resolve airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. Immunology 109, 295–299 (2003).

North, R.J. Mice incapable of making IL-4 or IL-10 display normal resistance to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 113, 55–58 (1998).

Higgins, D.M., Sanchez-Campillo, J., Rosas-Taraco, A.G., Lee, E.J., Orme, I.M. & Gonzalez-Juarrero, M. Lack of IL-10 alters inflammatory and immune responses during pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 89, 149–157 (2009).

Rosas-Taraco, A.G., Higgins, D.M., Sanchez-Campillo, J., Lee, E.J., Orme, I.M. & Gonzalez-Juarrero, M. Local pulmonary immunotherapy with siRNA targeting TGFbeta1 enhances antimicrobial capacity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infected mice. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 91, 98–106 (2010).

Beamer, G.L. et al. Interleukin-10 promotes Mycobacterium tuberculosis disease progression in CBA/J mice. J. Immunol. 181, 5545–5550 (2008).

Yahagi, A. et al. Suppressed induction of mycobacterial antigen-specific Th1-type CD4+ T cells in the lung after pulmonary mycobacterial infection. Int. Immunol. 22, 307–318 (2010).

Ioerger, T.R. et al. Variation among genome sequences of H37Rv strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from multiple laboratories. J. Bacteriol. 192, 3645–3653 (2010).

Manca, C. et al. Virulence of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolate in mice is determined by failure to induce Th1 type immunity and is associated with induction of IFN-alpha /beta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5752–5757 (2001).

Reed, M.B. et al. A glycolipid of hypervirulent tuberculosis strains that inhibits the innate immune response. Nature 431, 84–87 (2004).

Manca, C. et al. Hypervirulent M. tuberculosis W/Beijing strains upregulate type I IFNs and increase expression of negative regulators of the Jak-Stat pathway. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 25, 694–701 (2005).

Ordway, D. et al. The hypervirulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain HN878 induces a potent TH1 response followed by rapid down-regulation. J. Immunol. 179, 522–531 (2007).

Newton, S.M. et al. A deletion defining a common Asian lineage of Mycobacterium tuberculosis associates with immune subversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 15594–15598 (2006).

Torrado, E. & Cooper, A.M. IL-17 and Th17 cells in tuberculosis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 21, 455–462 (2010).

Eruslanov, E.B. et al. Neutrophil responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in genetically susceptible and resistant mice. Infect. Immun. 73, 1744–1753 (2005).

Keller, C., Hoffmann, R., Lang, R., Brandau, S., Hermann, C. & Ehlers, S. Genetically determined susceptibility to tuberculosis in mice causally involves accelerated and enhanced recruitment of granulocytes. Infect. Immun. 74, 4295–4309 (2006).

Cruz, A. et al. Pathological role of interleukin 17 in mice subjected to repeated BCG vaccination after infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 207, 1609–1616 (2010).

Aujla, S.J., Dubin, P.J. & Kolls, J.K. Th17 cells and mucosal host defense. Semin. Immunol. 19, 377–382 (2007).

Aujla, S.J. et al. IL-22 mediates mucosal host defense against Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. Nat. Med. 14, 275–281 (2008).

Okamoto Yoshida, Y. et al. Essential role of IL-17A in the formation of a mycobacterial infection-induced granuloma in the lung. J. Immunol. 184, 4414–4422 (2010).

Khader, S.A. et al. IL-23 and IL-17 in the establishment of protective pulmonary CD4+ T cell responses after vaccination and during Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Nat. Immunol. 8, 369–377 (2007).

Khader, S.A. & Cooper, A.M. IL-23 and IL-17 in tuberculosis. Cytokine 41, 79–83 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Leona Gabryšová and Finlay W. McNab for helpful discussions and critical reading of this review. A.O.G. and P.S.R. are funded by the Medical Research Council, UK. P.J.M. is supported by the NIH grant AI62921, the Hartwell Foundation, the NIH CORE grant P30 CA21765, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Redford, P., Murray, P. & O'Garra, A. The role of IL-10 in immune regulation during M. tuberculosis infection. Mucosal Immunol 4, 261–270 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2011.7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2011.7

This article is cited by

-

B cell-derived IL-10 promotes the resolution of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury

Cell Death & Disease (2023)

-

Correlation of angiogenic growth factors and inflammatory cytokines with the clinical phenotype of ocular tuberculosis

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2023)

-

Modulation of TDM-induced granuloma pathology by human lactoferrin: a persistent effect in mice

BioMetals (2023)

-

Antigen-specific B cells direct T follicular-like helper cells into lymphoid follicles to mediate Mycobacterium tuberculosis control

Nature Immunology (2023)

-

CD4+ICOS+Foxp3+: a sub-population of regulatory T cells contribute to malaria pathogenesis

Malaria Journal (2022)