Abstract

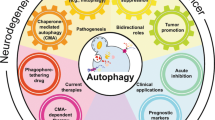

Autophagy is a cellular pathway involved in protein and organelle degradation, which is likely to represent an innate adaptation to starvation. In times of nutrient deficiency, the cell can self-digest and recycle some nonessential components through nonselective autophagy, thus sustaining minimal growth requirements until a food source becomes available. Over recent years, autophagy has been implicated in an increasing number of clinical scenarios, notably infectious diseases, cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and autoimmunity. The recent identification of the importance of autophagy genes in the genetic susceptibility to Crohn's disease suggests that a selective autophagic response may play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of common complex immune-mediated diseases. In this review, we discuss the autophagic mechanisms, their molecular regulation, and summarize their clinical relevance. This progress has led to great interest in the therapeutic potential of manipulation of both selective and nonselective autophagy in established disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ability to adapt to environmental change is essential for survival. This is true for the organism as a whole and for individual cells alike. The eukaryotic cell has developed myriad processes to recognize nutritional or microbial changes, both extra- and intracellularly. During cellular stress or starvation, the evolutionarily conserved autophagy response is used to recycle nutrients from nonessential or defunct cell organelles. In addition, the cell uses autophagy to clear its intracellular milieu of misfolded proteins or invading microorganisms.

We provide an overview from key initial discoveries to recent advances in the intracellular pathways involved in autophagy. The emphasis is on discoveries with direct relevance to the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity and to the pathogenesis of human inflammatory disease. We discuss the intriguing mechanisms connecting autophagy, apoptosis, and inflammation, as well as the role of autophagy in disease processes such as cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and Crohn's disease (CD). Therapeutic agents capable of manipulating the autophagic response are discussed and we show how both stimulation and inhibition of the autophagic response, depending on the clinical condition and the stage of disease, could be applied successfully.

The autophagy pathway

The term autophagy was first coined at the CIBA Foundation Symposium on lysosomes by Christian de Duve in 1963. Autophagy encompasses several distinct processes involving the delivery of portions of the cytoplasm to the lysosome for degradation: chaperone-mediated autophagy, micro-autophagy, and macro-autophagy. In chaperone-mediated autophagy, proteins that contain a specific pentapeptide motif are translocated directly into the lysosome for degradation, and this process requires the action of cytosolic and lysosomal chaperones. Micro-autophagy involves the sequestration of cytosolic components directly at the lysosomal surface. As illustrated in Figure 1, macro-autophagy is a membrane system that is initiated at a pre-autophagosomal structure or phagophore. A double-membrane isolation membrane then forms at the phagophore and encloses proteins, organelles, or pathogens to be degraded into an autophagosome. The autophagosome then fuses with the lysosome to form an autolysosome in which its contents are degraded by lysosomal hydrolases. The resulting macromolecules are released back into the cytosol through membrane permeases.

Schematic depiction of autophagy. (a and b) Cytosolic material is sequestered by an expanding membrane sac, the phagophore. (c) A double-membrane vesicle, the autophagosome, then forms at the phagophore and encloses proteins, organelles, or pathogens to be degraded. (d) The autophagosome then fuses with the lysosome to form the autolysosome in which its contents are degraded.

A better understanding of macro-autophagy in particular, offers high hope for the successful manipulation of autophagy. This therapeutic potential is notably for diseases characterized by dysregulation of the immune response against microorganisms (such as CD), of intracellular processing of misfolded proteins (such as in neurodegenerative diseases and CD), or of apoptosis (implicated in CD, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer). We will therefore focus on macro-autophagy (herein referred to as autophagy), and specifically on selective autophagy (e.g., induced by misfolded proteins or microorganisms entering the cytosol), rather than on nonselective (starvation induced) autophagy.

The molecular mechanisms of autophagy

Autophagy can be divided into three distinct stages: vesicle nucleation (formation of the so-called phagophore), vesicle elongation (growth and closure of the autophagosome), and fusion of the autophagosome with a lysosome to form an autolysosome.1 This process is controlled by the Atg (autophagy related) proteins.2 Atg proteins form distinct functional complexes, including a protein serine/threonine kinase complex that responds to upstream signals such as mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), which will be discussed in detail in the section on the regulation of autophagy. Initially, the cytosolic material is sequestered by an expanding membrane sac, the phagophore or isolation membrane. Although the phagophore assembly site (PAS) is the proposed site for autophagosome formation, the precise mechanisms of isolation membrane formation are unknown. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the PAS is a peri-vacuolar site to which most core Atg proteins localize.3, 4 Despite the lack of comprehensive studies, the colocalization of the core Atg proteins to PAS has also been observed in mammalian cells.5, 6, 7 For a comprehensive review of the core molecular machinery of autophagosome formation, readers are referred to Xie and Klionsky.2

In brief, autophagosomal membrane formation and expansion is mediated by two ubiquitin-like protein conjugation systems, the LC3 (Atg8) and Atg12 systems (Figure 2). Initially, the LC3 precursor is processed by the cystine protease Atg4 into the mature form of LC3 (LC3-I), which can then be modified by the ubiquitin E1-like protein, Atg7, and the ubiquitin E2-like protein, Atg3, to generate a smaller lipidated form of LC3 (LC3-II). Recruitment of LC3-II to the growing isolation membrane depends on the Atg12 system. Atg12 is activated by Atg7, then further modified by the ubiquitin E2-like protein, Atg10, and eventually covalently linked to Atg5. The Atg5–Atg12 complex then associates with Atg16 to initiate the elongation stage of isolation membrane formation by recruiting the lipidated LC3-II. Atg16 determines the site of LC3 lipidation through an interaction with the Golgi-resident small GTPase Rab33.8, 9

Molecular machinery of autophagosome formation. Autophagosomal membrane formation and expansion are mediated by two ubiquitin-like protein conjugation systems, the Atg8 (LC3) and Atg12 systems, whereas a recycling pathway mediates the disassembly of Atg proteins from matured autophagosomes (Atg2, Atg9, and Atg18). PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; G, glycine.

The LC3 is the only Atg protein in higher eukaryotes that remains associated with the mature autophagosome. The yeast, Atg8, has multiple paralogs in mammals, termed LC3A (with two splice isoforms, a and b, in humans), LC3B, GABARAP, GABARAPL1, and GABARAPL2 (GATE-16), encoded on different chromosomes, with the exception of LC3B and GABARAPL2, which are linked to chromosome 16 in the human genome.10 The LC3 routinely referred to in the literature is LC3B.10

The conversion of LC3-I to the membrane-associated lipidated form of LC3-II forms the basis for one of the assays that monitor autophagy levels.11, 12, 13 On completion of the autophagosome, the Atg5–Atg12–Atg16 complex dissociates from the outer autophagosomal membrane and is recycled together with LC3 (which then needs further delipidation by Atg4).14 In the maturation stage, the fraction of LC3 trapped on the luminal membrane of the autophagosome is degraded in the autolysosome.1, 12 Finally, a recycling pathway (comprising Atg2/Atg9/Atg18) mediates the disassembly of Atg proteins from matured autophagosomes.

Autophagosomal membrane formation differs between nonselective and selective autophagy.2 Both these forms of autophagy require specific adaptations of the core autophagic machinery.2 In nonselective autophagy, autophagosomes primarily contain bulk cytoplasmic contents.2 In contrast, selective autophagy in yeast (e.g., containing peroxisomes or bacteria) results in autophagosomes with a configuration similar to the cargo they envelop.15, 16, 17 The autophagic machinery is able to respond to information from the cargo to use it as a scaffold. In yeast, adaptor proteins, Atg11 and Atg19, interact with the core machinery (Atg1/LC3/Atg9) to wrap the isolation membrane around the cargo.18 These adaptations in selective autophagy have also been observed in mammalian cells in response to invading bacteria.19 Both PIP3, a product of the Vps34/beclin1 complex (see below), and LC3 have been suggested as such anchors for the envelopment of the substrate by autophagosomal membrane formation.20, 21

The regulation of autophagy

Early autophagy research implicated autophagy in the generation of energy during cellular starvation.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 First, metabolic hormones were shown to regulate autophagy, with glucagon inducing autophagy and insulin being inhibitory.28 Later, Mortimore et al.29 and Seglen et al.30 discovered the regulatory role of amino acids, the inhibitory action of 3-methyladenine, and the first evidence for the regulatory effects of protein kinases and phosphatases on autophagy.29, 30, 31 These findings underpinned our understanding of autophagy as an energy-generating catabolic mechanism at times of cellular starvation through the catabolism of cell components after their sequestration into autophagolysosomes.

In contrast to the ubiquitin proteasome system that selectively degrades single proteins, autophagy can degrade aggregate-prone proteins, protein complexes, and whole organelles by both selective and nonselective mechanisms. Starvation-induced autophagy is nonselective and involves large-scale degradation of the cytoplasm, therefore excessive levels of autophagy would be undesirable. On the other hand, autophagy is required to maintain minimal growth requirements and viability during starvation, therefore insufficient autophagy would also be undesirable: studies in Caenorhabditis elegans have shown that both low levels and excessively high levels of autophagy signal death in response to starvation, whereas intermediate levels signal survival.32 Autophagy is normally maintained at a constitutive/basal level, and is activated in response to a myriad of stimuli including nutrient deprivation, pathogens, cytokines, protein aggregates, and damaged organelles, thus autophagy must be a tightly regulated process.

The breakthrough in the investigation of the molecular regulation of autophagy came with the identification of the Target of Rapamycin (TOR) gene, and the observation that rapamycin, as an inhibitor of TOR, acts as an autophagy inducer.33, 34, 35 In mammalian cells, the best characterized regulatory pathways include the class I PI3K (phosphoinositide-3-kinase) and the mTOR, which act to inhibit autophagy, and the class III PI3K Vps34, which is paradoxically involved in both mTOR activation and the initiation of autophagosome formation (Figures 2 and 3).

Signaling, the regulation of nonselective autophagy and therapeutic options available to manipulate the autophagic response (For details of the signaling pathways and inhibitors indicated in the figure, refer to the main text). P, signal transduction through direct phosphorylation.

Before mammalian cells become committed to grow and proliferate, sufficient nutrients and energy must be available. A key pathway that senses and signals this information is the mTOR pathway (Figure 3). The serine/threonine kinase mTOR forms two types of multi-subunit complexes involving distinct partner proteins: TORC1 and TORC2.36 The form of mTOR that directly regulates cell growth is TORC1, which contains mTOR in complex with Raptor (regulatory-associated protein of mTOR), PRAS40 (proline-rich Akt substrate of 40 kDa, an inhibitor of mTOR), and GβL.36 The second complex, TORC2, differs in that it contains the binding partner, Rictor (rapamycin-insensitive companion of TOR).36 TORC1 is sensitive to rapamycin, whereas mTORC2 is insensitive to this compound. Only TORC1 (hereafter referred to as mTOR) is linked to the control of cell growth and autophagy. mTOR regulates the phosphorylation of a number of components of the translational machinery. In particular, phosphorylation and activation of 4E-BP1 and S6K1 are stimulated by serum insulin and growth factors in an mTOR-dependent manner.37

The TSC complex is a heterodimer composed of tuberin (TSC2) and hamartin (TSC1) and is the major regulator of the mTOR signaling pathway.38 TSC2 contains a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) domain that converts the small GTPase Rheb (Ras homolog enriched in brain) to its inactive GDP-bound form. mTOR activity is stimulated by the active GTP-bound form of Rheb, thus the TSC complex acts to inhibit mTOR function.38 The TSC complex integrates growth factor and cellular energy signaling with mTOR activity.

Signals from growth factor receptors are transduced to TSC1/2 through class I PI3K/Akt and Ras/Mek/Erk pathways, and from cellular energy sensing through the LKB-AMPK pathway.38 Factors that mediate nutrient (amino acid) signaling to mTOR include class III PI3K Vps34 and the Rag family of GTPases.39, 40 Insulin stimulates Akt through the class I PI3K pathway and, once active, Akt stimulates mTOR through phosphorylation of both TSC2 (inhibiting its Rheb-GAP activity) and PRAS40 (relieving its inhibition of mTOR).41 Growth factor signaling also stimulates the Ras/Mek/Erk pathway; once active, Erk phosphorylates TSC2 at different sites from Akt, also resulting in the inhibition of its Rheb-GAP activity.42 Conversely, metabolic stresses that reduce energy levels in the cell activate the LKB–AMPK pathway. AMPK has two inhibitory effects on mTOR: it phosphorylates TSC2 and promotes its Rheb-GAP activity, and it phosphorylates Raptor.43

mTOR inhibits autophagy indirectly by inhibiting the activities of the serine/threonine kinase, Atg1.44, 45 Starvation signals sensed by mTOR are transmitted to the Atg proteins, many of which accumulate at the PAS (Figure 2). In yeast, Atg1 interacts with Atg13 and Atg17, and its kinase activity is required for autophagy induction.46, 47 The Atg1 complex (Atg1/Atg13/Atg17) is essential for the recruitment of other Atg proteins to PAS during nonspecific autophagy; however, this does not require Atg1 kinase activity.48, 49 In mammals, two Atg1 homologs have been discovered, ULK1 and ULK2. The role of ULKs in autophagy induction has not yet been properly characterized; however, ULK kinase activity increases under starvation conditions, and kinase-dead mutants of ULK exert a dominant-negative effect on autophagosome formation.50 In addition, focal adhesion kinase family-interacting protein of 200 kDa (FIP200), a ULK-interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation as autophagosome formation is almost completely blocked in FIP200-deficient cells.50 It was also observed that ULK1, ULK2, and FIP200 localize to isolation membranes, suggesting that the ULK–FIP200 complex plays an essential role in the early stages of autophagosome formation.50

The class III PI3K, Vps34, has been extensively studied in the context of vesicular trafficking processes, and recent work has shown that Vps34 also plays an important role in the ability of cells to respond to changes in nutrient conditions.51 The activity of Vps34 requires the association of the protein kinase, Vps15 (Figure 2).52 When amino acids are plentiful, Vps34–Vps15 contributes to mTOR activation, thereby repressing autophagy. By contrast, the Vps34–Vps15–beclin1 (Atg6) complex initiates autophagosome formation.52 The Vps34–beclin1 complex can be activated by the beclin1-interacting proteins, UVRAG (UV radiation-resistant gene) and AMBRA1 (activating molecule in beclin1-regulated autophagy), and inhibited by another beclin1-interacting partner, Bcl-2 (B-cell lymphoma 2).52 Thus, depending on its binding partners, Vps34 is subject to different modes of regulation, leading to activation or inhibition of autophagy.

Beclin1, the first identified mammalian autophagy gene, interacts with several cofactors to activate the lipid kinase, Vps34, thereby inducing autophagy.53, 54 Beclin1 is a BH3-domain-only protein that binds to the BH3 domain of the antiapoptotic proteins, Bcl-2/Bcl-XL.55 Under normal conditions, beclin-1 is bound to and inhibited by Bcl-2 or the Bcl-2 homolog, Bcl-XL, and the dissociation of beclin1 from Bcl-2 is essential for its autophagic activity.54 Nutrient deprivation stimulates the dissociation either by activating BH3-only proteins (such as Bad), which can competitively disrupt the interaction, or by posttranslational modification of beclin1 or Bcl-2.54

Although mTOR is still considered to be the central regulator of autophagy, other types of regulations independent of mTOR, such as the Bcl-2/beclin1 complex and Atg4 regulation through c-Jun-N-terminal-kinase (JNK) and reactive oxygen species (ROS), have been described.56, 57, 58, 59 In addition, lowering the levels of the secondary messenger, myo-inositol-1-4-5 triphosphate (IP3), also induces autophagy in an mTOR-independent manner. The primary function of IP3 is to release calcium from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the cytoplasm, suggesting that autophagy might be modulated by calcium. Recently, a major mTOR-independent pathway has been described, involving links between Ca2+–calpain–Gsα and cAMP–Epac–PLC-ɛ- IP3 signaling.60, 61, 62

Selective autophagy in innate and adaptive immunity—xenophagy

The idea that autophagy is involved only in the nonselective, bulk degradation of proteins and organelles no longer holds true. In contrast to starvation-induced autophagy, selective autophagy, directed against specific proteins and invading microorganisms, has been shown to be critical in the regulation of the inflammatory response. Recent studies have shown selective degradation of proteins by autophagy. For example, IKK and NIK, two key regulators of the nuclear factor (NF)-κB signaling pathway, are selectively degraded by autophagy.63, 64 In addition, catalase, a key enzyme of the cellular antioxidant defence mechanism, is selectively degraded by autophagy.65 In this section, we will focus on the selective autophagy of microorganisms.

Bacteria

Autophagy is crucial in protecting mammalian cells against various bacterial pathogens that have gained access to the cytoplasm (Figure 4 and Table 1). Autophagy can eliminate invading microbes in a highly specific manner in the process termed xenophagy. A better understanding of autophagy has shed light on this mechanism by which individual cells dispose of an invading microorganism, thus preventing the infection and destruction of the infected cell.1

The autophagic response to bacteria, the interaction with pattern-recognition receptors (Toll-like and NOD-like) and the antigen presentation to the adaptive immune system through major histocompatability complex (MHC) class II molecules are illustrated. The autophagic response to viruses and the presentation of the viral nucleic acid to Toll-like receptor 7 inside an endosome, after digestion in the autolysosome.

Autophagy contributes to bacterial clearance in a number of distinct ways: targeting free cytosolic microorganisms, targeting phagosomes to aid in the clearance of their bacterial contents, by producing bactericidal peptides, and by offering protection against bacterial exotoxins.21 In response to a direct recognition of cytosolic bacteria, an autophagic response is triggered as shown by Nakagawa66 in the case of Streptococcus. These authors confirmed the role of Atg5 in the response against Streptococcus pyogenes in Atg5-knockout embryonic stem cells.66 Rikihisa67 and Rich et al.68 showed that autophagy is initiated during host infection by Rickettsia and Listeria, respectively. In the case of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Salmonella enterica, and Toxoplasma gondii, autophagy targets phagosomes containing bacteria to limit their survival in infected macrophages.69, 70, 71 In mice, autophagy is upregulated after induction by interferon (IFN)-γ through IRGs (immunity-related p47 GTPases).69 The human IRGM will be discussed in the section on inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

In addition to an increased fusion with lysosomes, the clearance of Mycobacterium is further facilitated by bactericidal peptides (after the lysosomal hydrolysis of polyubiquitinylated protein aggregates).72 Autophagy offers another type of protection from bacterial pathogenesis by conferring resistance to bacterial exotoxin, for example, during Vibrio cholerae infection.73 Gut epithelial cell lines resist cell death in response to the hemolytic exotoxin cytolysin of this noninvasive enteropathogen through the induction of autophagy.74, 75

Not surprisingly, bacteria have devised ways to alter the autophagic machinery for their own benefit. The microorganism may attempt to avoid recognition by, for example, Atg molecules (e.g., Shigella), by tampering with autophagosome formation (e.g., Mycobacterium), inhibiting fusion of the autophagosome with the lysosome (e.g., Listeria) or using the cargo of the autophagosome as a nutrient. Ogawa et al.17 showed that VirG, a surface protein of the invasive bacterium, Shigella flexneri, can interact directly with Atg5, and this interaction results in a sequestration of the pathogen into the autophagosome, where it is degraded. In epithelial cells, Shigella escapes autophagy by secreting IcsB through the type III secretion system.17 VirG binding to Atg5 is competitively inhibited by IcsB binding to VirG.17 In contrast, Suzuki et al.76 showed no role for VirG in the induction of autophagy in macrophages, suggesting that factors other than VirG are important for autophagy induction in macrophages. Notably, the absence of caspase-1 and the NOD (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain)-like receptor, Ipaf, during the Shigella infection of macrophages, was found to potently induce autophagy.76 Together, these findings raise the question whether the autophagic response to invading bacteria is regulated differently in different cell types, with possible repercussions on the ensuing tissue-specific immune response.77

The intracellular survival of M. tuberculosis is dependent on its ability to arrest phagolysosome biogenesis, avoid direct killing mechanisms in macrophages, and block efficient antigen processing and presentation.78 The Mycobacterium-imposed block in phagolysosomal maturation can be overcome by activating cellular autophagy, either through starvation or through the inhibition of mTOR.69 Listeria monocytogenes (possibly by damaging the autophagosomal membrane through the pore forming toxin, Listeriolysin O) and several other pathogens, such as Francisella tularensis, Brucella abortus, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Leishmania mexicana, Chlamydia trachomatis, Coxiella burnetii, Legionella pneumophilia, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum, seem to maintain their replication by preventing autophagosomal maturation to degradative compartments.21, 79

How are pathogens that have gained access to cytosol recognized by the autophagic machinery? A distinction should be made here between the adjuvant effect of autophagy on the intracellular killing of pathogens contained within phagosomes after phagocytosis on the one hand, and the primary formation of autophagosomes to restrain pathogens that have gained access to cytosol, on the other hand.

Sanjuan et al.19 showed the link between Toll-like Receptor (TLR) signaling in macrophages and Atg5/Atg7-dependent autophagy and phagocytosis. Importantly, the translocation of beclin1 and LC3 to the phagosome was not associated with observable double-membrane structures characteristic of conventional autophagosomes, but was associated with phagosome fusion with lysosomes, leading to a rapid acidification and an enhanced killing of the ingested organism.19 Although Sanjuan et al.19 proposed that this indicated a role for the autophagic machinery involved in endosome maturation, Munz21 recently suggested that these single-membrane vesicles could represent amphisomes, intermediary vesicles in macro-autophagy that are not surrounded by a double membrane, and thus resemble late endosomal multi-vesicular bodies. Therefore, a part of the enhanced phagosome fusion with lysosomes could occur after autophagosome fusion with late endosomes.21

Earlier, Xu et al.80 had shown that TLR4-induced autophagy was regulated through a Toll-interleukin 1 receptor domain-containing adaptor-inducing IFN-β (TRIF)-dependent signaling pathway, also involving receptor-interacting protein-1 (RIP1) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), independent of the signal transduction molecule, MyD88 (myeloid differentiation factor-88). An hierarchy of signaling potency is emerging from these studies with regard to the induction of autophagy by TLR signaling.21 Together with TLR4, TLR7/8 mediates the strongest signaling. Delgado et al.81 showed in RAW 264.7 macrophages that, although several TLR ligands induced autophagy (e.g., zymosan (TLR2), polyinosinicpolycytidylic acid (TLR3), lipopolysaccharide (TLR4), single-stranded RNA (TLR7), and imiquimod (TLR8)), single-stranded RNA and TLR7 generated the most potent effects, dependent on MyD88 expression. It is relevant to our discussion of potential therapeutic implications of autophagy manipulation that stimulation of autophagy with TLR7 ligands was functional in eliminating intracellular microbes even when the target pathogen was normally not associated with TLR7 signaling.81 Sci and Kehrl recently showed that this TLR-mediated induction of autophagy was because of the regulation of beclin1 binding to its inhibitor, Bcl-2.82 MyD88 and Trif (Toll-interleukin 1 receptor domain-containing adaptor protein inducing IFN-β) co-immunoprecipitated with beclin1, a key factor in autophagosome formation. TLR signaling enhanced the interaction of MyD88 and Trif with beclin1, and reduced the binding of beclin1 to Bcl-2.82

Supported by these advances in our understanding of TLR–autophagy interactions, the investigation of intracellular pattern recognition receptor-mediated regulation of autophagy has recently been the subject of intense research. Nuñez and colleagues83 showed the interaction between NOD-like receptor (NLR) signaling and autophagy in macrophages by showing that Shigella-induced caspase-1 activation and cell death in macrophages are mediated through Ipaf/NLRC4, a cytosolic pattern-recognition receptor of the NLR family, and the adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (ASC), containing a C-terminal caspase recruitment domain. Notably, infection of macrophages with Shigella induced autophagy, which was dramatically increased by the absence of caspase-1 or Ipaf, but not ASC. This downregulation of autophagy was shown to be specific to Shigella-induced autophagy, as autophagy from serum starvation or rapamycin treatment did not require NLRC4 or caspase-1.84 It remains unclear how this mechanism interacts with the secretion of IcsB by Shigella as described above. The reason for the inhibition of autophagy by NLRC4 is not clear, but Nuñez and colleagues have proposed that this inhibition allows the induction of pyroptosis, which may better promote an effective inflammatory response.76 It is noteworthy that the Shigella-derived ligand triggering this Ipaf/NLRC4 is not flagellin, as Shigella does not express flagellin genes.84 Whether organisms expressing flagellin (e.g., Salmonella, Pseudomonas, and Legionella) inhibit autophagy through flagellin-induced Ipaf/NLRC4 signaling remains the subject of intense investigation.

In the fly, Drosophila melanogaster, induction of autophagy by diaminopimelic acid-type peptidoglycan, the ligand of NOD1/CARD4, has been shown to be essential for the prevention of intracellular growth of the bacterium, L. monocytogenes, and for host survival during infection with this pathogen.85 Preliminary mammalian data were presented by Dana Philpott at Toll 2008, alluding to an interaction between the intracellular microbial pattern recognition receptors, NOD1/CARD4 and NOD2/CARD15, and the autophagy pathway (D. Philpott, personal communication).86 In this context, it is tempting to speculate how intracellular innate immune receptors are triggered by bacterial ligands. Several organisms known to induce autophagy (e.g., Listeria and Streptococcus) have recently been shown to use their bacterial secretion systems to form pores to escape phagosomes after phagocytosis or to prevent autophagosomal maturation, as well as to transport bacterial products. For example, the aforementioned pore-forming toxin, listeriolysin, produced by Listeria, and pneumolysin (secreted by S.pneumoniae) permit the delivery of peptidoglycan, which is recognizable by NOD1/CARD4 and NOD2/CARD15, especially in non phagocytosing cells, such as epithelial cells.84, 87, 88, 89

Another plausible mechanism by which microorganisms induce autophagy is the generation of ROS in response to pathogen recognition by the host cell.17, 57, 90, 91 Tattoli et al.90 recently described a new member of the NLR family, NOD9/NLRX1, which localizes to the mitochondria. Although NLRX1 alone failed to trigger most of the common signaling pathways, including NF-κB- and type I IFN-dependent cascades, it could potently trigger the generation of ROS.90 Importantly, NLRX1 synergistically potentiated ROS production induced by tumor necrosis factor-α, Shigella infection, and double-stranded RNA, resulting in amplified NF-κB-dependent and JUN amino terminal kinases (JNK)-dependent signaling. As discussed above, JNK signaling has been shown to induce autophagy through Atg4.57 Although the precise ligand responsible for the activation of NOD9/NLRX1 remains elusive, in silico phylogenetic analysis of LRR (leucine-rich repeat) domains from human NLRs has shown that NOD9/NLRX1 LRR has homology with a subgroup of NLRs containing NOD1 and NOD2.90 The identification of this novel member of the NLR family and its interaction with the autophagic machinery through the induction of ROS are therefore promising new research angles in our quest to understand the regulation of autophagy by innate immune receptors.

Viruses

In antiviral immunity, the interaction of the autophagic response with viruses can lead to several distinct outcomes; notably, the restriction of viral replication, the restriction of pathogen-induced cell death, the inhibition of autophagy by viruses to increase viral replication, or the use of the autophagic machinery (or accumulated autophagosomes) for viral replication.1 Experiments with alphaviruses and the herpes simplex virus (HSV) in cells and mice have shown the importance of autophagy in the immune response against viruses.53, 92, 93 However, to date, only HSV1 has been shown within autophagosomes.1 The single-stranded RNA Hepatitis C virus (Flaviviridae), double-stranded RNA rotavirus of the reovirus family, and the single-stranded DNA B19 parvovirus have all been shown to induce autophagy.73

The precise mechanism by which autophagy is induced by viral infection of the host cell is gradually being elucidated. The strategies used by viruses to avoid autophagy or to exploit the machinery to their benefit have been instrumental in bringing about a greater understanding of the autophagic machinery involved in the antiviral innate immune response.55, 93 For example, the HSV neurovirulence protein, ICP34.5, confers pathogenicity by binding to beclin1 and inhibiting the host autophagic response dependent on PKR (IFN-inducible double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase), and PKR-deficient mice were unable to control mutant HSV1 infection.93 Other viruses, such as gammaherpesviruses, encode Bcl-2-like proteins that inhibit beclin1.55 Similar to HSV, other viruses also inhibit the PKR antiviral signaling pathway that is required for the induction of autophagy in virally infected cells or to activate the autophagy-inhibitory class I PI3K–AKT–mTOR-signaling pathway.1 The vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) has recently been shown to downregulate autophagy in the Drosophila host cell by repressing the serine–threonine kinase Akt (S. Cherry, Philadelphia, PA, USA, presented at Toll 2008).86

It is still unclear to what extent viruses exploit the autophagic machinery to obtain membrane anchors for their cytoplasmic replication and subvert the autophagic pathway (e.g., by stimulating autophagy but inhibiting autophagosome degradation) or use a partially overlapping pathway that is involved in membrane trafficking and rearrangement.1 Recent studies have shown that the role of autophagy in innate antiviral immunity is unlikely to be confined to direct pathogen elimination.(Figure 4 and Table 1) In their landmark paper, Lee et al.94 described how the autophagic machinery delivers viral genetic material (of Sendai virus and VSV, both single-stranded RNA viruses) to endosomal TLRs in plasmacytoid dendritic cells in vitro (dependent on ATG5 and TLR7), resulting in type I IFN production and the so-called “topological inversion.”10, 94 In this process, the autophagic machinery sequestrates cytosolic proteins into the autophagosome, wherein they then face the lumen of endomembranous compartments, which puts them on the same side of the membrane as that of the major histocompatability complex (MHC) II groove, after fusion with an endosome containing TLR7/8.10 In turn, TLR7/8 signaling constitutes one of the strongest triggers for the induction of autophagy, as mentioned above.10, 81 In the next section, the relevance of this topological inversion for priming of the adaptive immune response will be discussed.

Similar to the autophagic response against bacteria, these findings may be cell-type specific, so that stimulation of autophagy could lead to an increased viral replication.21 VSV infection of mouse embryonic fibroblasts elicited less type I IFN in the presence of autophagy than in its absence. The cytosolic RNA helicase retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), an intracellular pattern recognition receptor, seemed primarily to mediate the stimulation of type I IFN production in VSV-infected mouse embryonic fibroblasts, and Atg5–Atg12 conjugates interacted directly with RIG-I and the downstream-type I IFN effector, IFN-β promoter stimulator 1, through their caspase recruitment domains.21, 95 Other RNA viruses (e.g., poliovirus, dengue virus, and rhinovirus) also use the autophagic machinery to facilitate their replication within autophagosomes while inhibiting their degradation. For example, the polio viral replication machinery is assembled on the surface of double-membrane vesicles (containing LC3), and autophagy inhibition decreased virus production, whereas autophagy stimulation increased the poliovirus yield.96

Autophagy, antigen presentation, and the adaptive immune response

The role of autophagy in immune response is not limited to the direct elimination of invading pathogens. Degradation products of the proteasome and lysosomal pathways are processed for presentation to MHC molecules and for activation of the adaptive immune response. There are two primary classes of MHC molecules. MHC class I molecules are found on almost every cell type, whereas MHC class II molecules are only found on a few specialized cell types, including macrophages, dendritic cells, and B cells, all of which are professional antigen-presenting cells. In general, peptides generated by proteasomal degradation are derived from intracellular proteins, whereas peptides generated by lysosomal degradation are derived from extracellular proteins. Loading of MHC class II molecules occurs inside the cell, therefore extracellular proteins are endocytosed, digested in lysosomes, and bound by the MHC class II molecule before the molecule's migration to the plasma membrane.

There is mounting evidence that a substantial proportion of MHC class II peptides are derived from intracellular long-lived proteins within cell organelles or protein aggregates, which are not efficiently processed by the proteasome, and that autophagy is involved in the delivery of these ligands to the MHC class II molecule.21, 97 It is estimated that around 20–30% of MHC class II-bound peptides originate from cytosolic and nuclear proteins, likely as a result of autophagic pathways.98 Loading of the MHC class II through autophagy has also been shown for pathogen-derived proteins. For example, endogenous Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 was found to gain access to MHC class II through autophagy.99 Furthermore, components of the core autophagic machinery, such as LC3, have been isolated from human and mouse MHC class II molecules.98 Peptides generated by lysosomal degradation are presented on MHC class II molecules to CD4+ T cells, thus autophagy may stimulate CD4+ T-cell responses against pathogens.100, 101

This finding of cross-presentation of endocytic antigens on MHC class I and autophagy-derived epitopes on MHC class II could also be used to assess the regulation of autophagy.102 Antigens fused to the N-terminus of LC3 get preferentially presented on MHC class II molecules, and the localization of LC3-fusion antigens in MHC Class II can be visualized by confocal microscopy. MHC class II presentation can also be quantified in a presentation assay with antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell clones. These assays are good measures of autophagosome formation and lysosomal degradation of macroautophagy cargo and are therefore useful for studying the regulation of the autophagic pathway under various experimental conditions and physiological perturbations.102

The additional function of the autophagic machinery in MHC class II antigen presentation is also crucial in the development of T cells, notably in the presentation of self-antigens in the newborn thymus, enabling thymic epithelial cells to present self-antigens to lymphocytes during positive and negative selection. Nedjic et al.103 showed that, in contrast to most other tissues, thymic epithelial cells had a high constitutive level of autophagy. Genetic interference with autophagy, specifically in thymic epithelial cells, led to an altered selection of certain MHC-II-restricted T-cell specificities and resulted in severe colitis and multi-organ inflammation. Increasingly, this extended role of the autophagic machinery in regulating the adaptive immune response is also recognized to be crucial in antigen presentation by B cells, dendritic cells, and epithelial cells.100, 101 Autophagy could therefore also play a role in the induction of the so-called peripheral tolerance by regulating autoreactive T cells that have escaped negative selection in the thymus.21

In addition to its role in antigen presentation, autophagy also plays a role in T- and B-lymphocyte homeostasis and in clonal expansion.21, 104, 105 One hypothesis for the observed decrease in T-cell survival in Atg5−/− mice is that these cells are exposed to nutritional stress after their exit from the thymus and require autophagy to sustain them.106 B cells also require Atg5 for their development in the bone marrow as well as for their maintenance in the periphery, as recently shown by Miller et al.105 Conversely, excessive autophagy has been linked to the cell death of effector T cells, more so in the case of Th2 than in that of Th1 cells.107 Whereas resting naive CD4+ T cells do not contain detectable autophagosomes, autophagy can be observed in activated CD4+ T cells on T-cell receptor stimulation, cytokine culturing, and prolonged serum starvation, dependent on JNK signaling and the class III PI3K. Interestingly, more Th2 cells than Th1 cells undergo autophagy. Th2 cells become more resistant to growth factor-withdrawal cell death when autophagy is blocked.107 The importance of autophagy regulation in T- and B lymphocytes in response to a wide variety of stimuli in physiological and pathological conditions therefore adds a further layer of complexity to the role of autophagy in the development of human diseases (as discussed in the next section, and the potential of the successful manipulation of the autophagic response as discussed thereafter).

Autophagy, apoptosis, and inflammation: pathogenesis to potential therapeutic applications

Basal autophagy differs among tissues, being particularly important in the liver and in other tissues in which cells do not divide after differentiation (e.g., neurons and myocytes). Autophagy prevents the accumulation of abnormal protein aggregates, is involved in the maintenance of genomic stability, and can mediate the removal of intracellular pathogens. It is therefore not surprising that autophagy has been linked to a wide range of diseases including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, susceptibility to infections, and CD (Table 1).

Cancer

Cancer was one of the first diseases to be linked to autophagy. The Atg gene, beclin1 (Atg6), is deleted in 40–50% of breast, ovarian, and prostate cancers.108 Several other genetic links between defects in autophagy and cancer have been reported, and many proteins that function as positive regulators of autophagy are also tumor suppressors. Notably, p53, the most commonly mutated tumor-suppressor gene in human cancers, has been shown to regulate autophagy.109, 110 Although the molecular mechanisms by which autophagy can suppress tumor formation are still elusive, the successful manipulation of autophagy in cancer treatment will likely depend on the type and stage of the cancer.111

Autophagy may suppress tumor formation by limiting genomic instability and DNA damage. It accomplishes this by degrading damaged proteins and organelles that might otherwise interfere with normal cellular processes (e.g., mitochondria). Mitochondria are the major energy-generating organelles within the cell, and ROS are among the by-products of the energy-generating process. ROS are usually maintained at low levels in cells by antioxidant molecules. When mitochondria malfunction, excessive ROS can reach the nucleus and increase the frequency of mutation of DNA. Cells with deletion of beclin1 or Atg5 display increased DNA damage, gene amplification, and aneuploidy.112 Thus, enhancing the level of autophagy would lower the chance of genomic instability by preventing the accumulation of damaged protein, DNA, and ROS in the cell. Temozolomide, a pro-autophagic cytotoxic drug, has shown real therapeutic benefits in glioblastoma patients, and is in clinical trials for several types of apoptosis-resistant cancers.113 Another example is tamoxifen, which functions in part by stimulating beclin 1 and upregulating autophagy.114

Another mechanism through which autophagy may suppress tumorigenesis is by limiting cell proliferation and tumor development by promoting apoptosis. The relationship between autophagy and apoptosis is complicated. Although autophagy often precedes apoptosis as a last rescue attempt to avoid cell death,73, 115 it has been proposed that autophagy can contribute to cell death in a process termed autophagic (Type-II) cell death. In some circumstances, inhibition of autophagy can induce cell death. For example, cells cultured in nutrient-deprived conditions induce autophagy in order to recycle nonessential cellular components and fuel the cell. Under these conditions, the inhibition of autophagy results in rapid cell death, which can be prevented by the inhibition of caspases, suggesting that eventual cell death is apoptotic.116 Stimulation of autophagy may also mediate cell death. Autophagy can destroy large amounts of cytosol and organelles; therefore, excessive levels of autophagy would cause irreversible cell atrophy that would eventually result in cell death. In the D. melanogaster model system, stimulation of autophagy by overexpression of Atg1 resulted in a cell death that resembled apoptosis, and could be blocked by the deletion of essential autophagy genes or delayed by inhibition of caspases.117 These studies suggest that autophagy can indirectly trigger cell death through the induction of apoptosis. Autophagy may also induce cell death through non-apoptotic pathways such as necrosis. Catalase, an enzyme that functions in cellular antioxidant defense, is selectively degraded by autophagy, leading to necrotic cell death, which can be blocked by autophagy inhibition and antioxidants.43 The elimination of cytoprotective proteins such as catalase may lead to irreversible cellular damage and death. Thus, stimulation of autophagy may be therapeutically useful in promoting autophagic cell death or in preventing the damaging effects arising from autophagy deficiency.

Autophagy may provide an energy source that maintains tumor cell survival in low-vascularized, low-oxygen, low-nutrient conditions and thus could favor disease progression.118, 119, 120, 121, 122 Therefore, inactivation of autophagy would prevent tumor cells from surviving in nutrient-deficient conditions. In a mouse model of lymphoma, both the drug chloroquine and Atg5 inhibition with RNA interference sensitized tumors to death induced by p53 or by a DNA-alkylating agent.123

In summary, stimulating autophagy may be effective in preventing tumor formation, whereas inhibition of autophagy may be helpful in promoting tumor regression through an enhanced chemosensitivity of the tumor.124

Neurodegenerative disorders

Formation of intracellular aggregates is characteristic of many neurodegenerative disorders, and defects in autophagy-related pathways contribute to the accumulation of neurotoxic proteins and the ensuing neuronal cell death. A steady-state, constitutive level of autophagy is an important protein quality-control system, particularly in the nervous system; mice deficient in autophagy genes develop neurodegenerative disorders.125, 126 Autophagy has been implicated as a protective mechanism in various neurodegenerative diseases such as those of Huntington, Parkinson, and Alzheimer, by removing protein aggregates or defective proteins.127, 128, 129

Huntington disease is caused by a polyglutamine-expansion mutation in Huntingtin that makes the protein toxic and aggregate prone.130 It is still a matter of debate as to whether the aggregates are responsible for disease. In Huntington disease, it has been suggested that the large mutant protein aggregates mediate their own clearance by sequestering and inactivating mTOR, thus activating autophagy.131, 132 Sequestration of beclin1 in the aggregates may contribute to the age-related decrease in beclin1 expression and therefore to the inhibition of autophagy.131, 133 Thus, polyglutamine protein aggregates can themselves regulate autophagy independent of mTOR signaling, raising the intriguing possibility that mutant protein- and starvation-induced autophagy may use different mechanisms to activate autophagy. It has therefore been suggested that autophagy may eliminate protein aggregates in a directed manner.134, 135

The p62/sequestosome-1 protein is an adaptor protein involved in multiple signaling pathways, and is present in ubiquitin-related inclusions such as those seen in various neurodegenerative diseases.136, 137 p62 contains both ubiquitin- and LC3-binding domains and is thus able to directly associate with LC3 and the ubiquitinated protein aggregates, therefore possibly mediating the recognition of the monomeric and oligomeric aggregate precursor proteins by the autophagosomes.20, 138 In support of this idea, intracellular levels of p62 are controlled by autophagy, although a direct relationship between p62 removal by autophagy and inclusion body formation has yet to be shown.134, 138 Although the role of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway in neurodegenerative diseases is controversial, autophagy mediates the clearance of aggregate-prone proteins.21

In Alzheimer disease, autophagosome-like structures accumulate because of their inability to fuse with lysosomes and mature into autolysosomes, providing a novel site for the cleavage of the Amyloid β (Aβ) precursor protein into the toxic proteolytic Aβ protein.139 Beclin1 has been found to be decreased in the affected brain regions of patients with Alzheimer disease, early in the disease process.140 In transgenic mice that express the human Amyloid precursor protein, a model for Alzheimer disease, a genetic reduction of beclin1 expression increased intraneuronal Aβ accumulation, extracellular Aβ deposition, neurodegeneration, and caused microglial changes and profound neuronal ultrastructural abnormalities.140

Altering the clearance of aggregate-prone proteins through the induction of selective autophagy is therefore an interesting therapeutic target.62 Drugs that induce autophagy, such as the mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin, mTOR-independent regulators of autophagy such as lithium (which lower IP3 levels), and other recently identified small molecules enhance their clearance and show promise as possible therapeutic agents.60, 141, 142 Promising results in the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with the autophagy inducer, lithium, have led to great excitement.143 Similar to the treatment of cancer, the benefits of manipulating autophagy for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders will depend on the type and stage of the disease.

Inflammatory bowel disease

The IBDs, CD and ulcerative colitis, are chronic incurable diseases that occur as a result of acute and chronic inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. Both childhood- and adult-onset CD are characterized by a progressive disease course in terms of location of disease as well as disease behavior (e.g., structuring or fistulizing complications).144 The involvement of the ileum is noteworthy, as this is rarely a presenting feature in childhood but becomes involved as children with CD approach adulthood.144, 145 The antimicrobial Paneth cells are abundantly present in the crypts of the ileum in the healthy state, but in CD, they are characteristically also present in the colon, then termed “Paneth cell metaplasia.”

The autophagy genes, Atg16L1 and IRGM, are among the more than 30 susceptibility loci for CD that have been identified to date using genome-wide association studies.146 Autophagy has been implicated in limiting inflammation by eliminating pathogens, blocking cell necrosis, and controling NF-κB signaling.

Tumor cells that have not been successfully removed by apoptosis or autophagy are removed by necrotic cell death. Necrosis leads to activation of inflammatory responses;147 thus, preventing cell necrosis is an important mechanism through which autophagy regulates inflammation. It has been shown that the removal of apoptotic cell corpses and necrotic cell debris is necessary to avoid excessive recruitment of neutrophils and to prevent chronic inflammation.147, 148 Consistent with this, mice lacking Atg5 display a defect in apoptotic corpse engulfment during embryonic development.149 Interestingly, the loss of tolerance against self-antigens because of defective clearance has been implicated in systemic lupus erythematosus pathophysiology.150

Another mechanism through which autophagy may regulate inflammation is through NF-κB. NF-κB is a master regulator of the inflammatory response and, as mentioned earlier, autophagy can selectively degrade NIK and IKK, resulting in the activation of NF-κB signaling.63, 64 Whether inadequate removal of apoptotic/necrotic cells, misregulation of NF-κB signalling, or defective pathogen clearance through a defect in the autophagic machinery contributes to IBD is currently the subject of intense investigation.

The different genome-wide association studies in CD and the meta-analysis of several of these genome-wide association studies have identified a number of genes involved in the regulation of the Th17-cell population, notably IL23R, JAK2, STAT3, and ICOSLG.146, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155 The recent report by Guo et al.,156 showing that Th17-mediated autoimmune disease (in this case, a murine model of multiple sclerosis) is constrained by TRIF-dependent type I IFN production and its downstream signaling pathway, is also pertinent for our understanding of the pathogenesis of CD, as it provides the first evidence for a potential link between the autophagy pathway and the development of Th17 cells. In the remainder of this section, we will discuss the autophagy genes, ATG16L1 and IRGM, as well as putative CD susceptibility genes, LRRK2 and XBP1 (X-box-binding protein 1), in view of their relevance to the autophagy pathway.

ATG16L1

Hampe et al.157 showed an association of CD with a coding variant of the Atg16L1 gene (autophagy-related 16-like 1 gene). Rioux et al.152 later showed that autophagy induced by S. Typhimurium was significantly different in Atg16L1 knockdown conditions. This genetic association has now been replicated in several independent cohorts.146, 152, 154, 155, 158 It is noteworthy that this association signal seems to be driven by the ileal disease location of CD.159, 160 Recent reports by Cadwell et al.,161 Saitoh et al.,162 and Kuballa et al.163 constitute a real breakthrough in our understanding of the ATG16L1 function, and firmly implicate the homeostasis and anti-microbial properties of the Paneth cell.

Cadwell et al.161 showed that, in the epithelium of the ileum, ATG16L1 and ATG5 are crucial for Paneth cell biology. ATG16L1-deficient Paneth cells exhibit notable abnormalities in the granule exocytosis pathway and an increased expression of genes involved in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor signaling, as well as several acute phase reactants and adipocytokines (notably leptin and adiponectin). CD patients, homozygous for the risk allele, identified by Hampe et al.,157 displayed Paneth-cell granule abnormalities such as those observed in ATG16L1-deficient mice.161

On the other hand, Saitoh et al.162 showed in ATG16L1 deficient mice that ATG16L1 is required to survive the period of neonatal starvation, as shown before for ATG5 and ATG7, and also showed an increased severity of colitis when induced by dextran sulfate sodium. The loss of ATG16L1 in macrophages caused aberrant lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-1β and IL-18, because of the activation of caspase-1 in a TRIF-dependent manner.162

Using a knockdown reconstitution strategy in human epithelial cells (HeLa and Caco2), Kuballa et al.163 showed that homozygosity for the ATG16L1 risk allele, identified by Hampe et al.,157 resulted in a reduced capture of S. Typhimurium within autophagosomes. These authors further showed that the wild-type (ATG16L1*300T) and mutant (*300A)-coding variants are both fully competent in mediating basal autophagy and that there is no difference between the two in allowing dimerization or binding to Atg5 in HeLa and HEK293T cells, respectively. Taken together, these studies implicate several distinct functions of Paneth cell biology, notably the capture of microorganisms within autophagosomses, the exocytosis of antimicrobial peptides, and the orchestration of the immune response. However, the true effect of some of these genetic variants may only become clear when these genetic variants are studied in the setting of a high microbial load and when other genetic variants associated with CD susceptibility are taken into account (e.g., TLR4 and NOD2/CARD15).

IRGM

Another autophagy gene, IRGM, was implicated in the susceptibility to CD by the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium study.154 IRGM belongs to the p47 immunity-related GTPase family. Its mouse homolog, LRG-47 (encoded by IRGM), critically controls intracellular pathogens by autophagy, and Irgm–/– mice show markedly increased susceptibility to T. gondii and L. monocytogenes.164 Singh et al.165 showed that the murine Irgm1 protein (immunity-related p47 guanosine triphosphatase, also called LRG47) is critical in the IFN-γ-induced autophagy response against M. tuberculosis.

The role of IRGM in protecting mature effector CD4+ T lymphocytes against IFN-γ-induced autophagic cell death has shown a feedback mechanism in the Th1 response that limits the detrimental effect of IFN-γ on effector T-lymphocyte survival while facilitating the antimicrobial functions of IFN-γ.166 An alteration in IRGM regulation because of a common deletion polymorphism in the promoter region of IRGM, which affects the efficacy of autophagy, is postulated in CD.167

LRRK2

The meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in CD identified the locus containing LRRK2 (leucine-rich repeat kinase 2) and MUC19 to be associated with risk of CD.146 Although detailed sequencing of the LRRK2 gene in IBD patients remains to be undertaken, LRRK2 mutations have been shown to be the single most common genetic cause of Parkinson disease.168 Transfection of LRRK2 cDNA containing the common G2019S mutation resulted in significant decreases in neurite length and in increased autophagic vacuoles.169 RNA interference knockdown of LC3 or Atg7 reversed the effects of the G2019S LRRK2 expression on neuronal process length, whereas rapamycin potentiated these effects. It remains to be elucidated whether these effects were because of a direct effect of LRRK2 on the autophagy pathway or indirectly, (e.g., through other signaling pathways such as MAPK).

XBP1—ER stress and autophagy

When cells are stimulated to secrete large amounts of protein (e.g., in response to viral infection), an excess of unfolded proteins accumulates in the ER, triggering ER stress and activating the so-called “unfolded protein response,” with a key role for the transcription factor XBP1.170, 171 These signaling pathways expand the protein-folding capacity of the cell in order to restore ER homeostasis. Not only is XBP1 deletion in IECs associated with spontaneous enteritis and increased susceptibility to induced colitis (secondary to both Paneth cell dysfunction and an epithelium that is overly reactive to mediators of inflammation in IBD, such as flagellin and TNFá), but a genetic association of XBP1 tagging variants with both CD and ulcerative colitis has also been described recently by Kaser et al.172

If the ER damage is extensive or prolonged, cells typically undergo programed cell death. The loss of key proteins of unfolded protein response also results in the so-called “unresolved ER stress” and apoptosis. For example, in the absence of XBP1, unresolved ER stress leads to an increased expression of select genes of the unfolded protein response and increased JNK signaling. These elevated signals increase cell susceptibility to programed cell death and induce an increased expression of proinflammatory genes, leading to intestinal inflammation. However, in response to JNK signaling, autophagy is induced and contributes to cell survival as shown by Ogata et al.173 Taken together, these studies provide functional and genetic evidence for the interaction between autophagy and ER stress response in the pathogenesis of IBD.

Autophagy: potential therapeutic applications

Inhibitors of mTOR (e.g., rapamycin and its analog, CCI-779) are commonly used to induce autophagy (Figure 3), and can protect against neurodegeneration in Drosophila and mouse disease models.132 Rapamycins are lipophilic macrolide antibiotics that form a complex with Tacrolimus/FK506-binding protein-12(FKBP12), which then binds to and inactivates mTOR, resulting in an increase in autophagy. However, rapamycins likely only induce nonselective autophagy similar to starvation, causing substantial side effects: inhibition of mTOR (a major regulator of the cell cycle and proliferation) represses the translation of numerous proteins, and prolonged mTOR inhibition will result in immunosuppression. Indeed rapamycin is in routine clinical use as an immuosupressant for organ transplantation. There has been much interest in the development of small-molecule inhibitors of mTOR catalytic activity, which may upregulate autophagy in a manner similar to rapamycin but hopefully with less unwelcome side effects.

Autophagy can also be induced in an mTOR-independent manner by lowering myo-inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) levels (Figure 3). IP3 is a second messenger that mediates calcium release from the ER to the cytoplasm. This can be achieved with drugs such as lithium, carbamazepine, and sodium valproate.21, 60

Recently, a screen of Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs identified L-type Ca2+ channel antagonists, the K+ATP channel opener minoxidil and the G(i) signaling activator clonidine, as inducers of autophagy, through a cyclical mTOR-independent pathway involving the regulation of IP3 concentration.61 Given that the mTOR and IP3 pathways are not thought to overlap, it is possible that autophagy could be induced to a greater extent by treatment with a combination of drugs that inhibit both pathways.127

Another possible strategy for stimulating autophagy is to disrupt the beclin1(Atg6)–BCL2 interaction. BCL2 inhibits the activity of the Vps34–beclin1 complex and thus inhibits autophagy. Indeed, small interfering RNA-mediated knockdown of BCL2 and drugs that target BCL2 result in the stimulation of autophagy.54 Tamoxifen, a drug that competes with estrogen for receptor binding and is commonly used in the treatment of breast cancer, also promotes an increased synthesis of beclin1 and thus stimulates autophagy.114

Conversely, inhibitors of autophagy (Figure 3), such as 3-methyladenine (inhibitor of class III PI3K), wortmannin (inhibitor of class I and class III PI3K, overall effect is to inhibit autophagy), chloroquine (diffuses into lysosome, elevates lysosomal pH, and inhibits autophagy), and bafilomycin A1 (blocks vacuolar ATPase activity, elevates lysosomal pH, and inhibits autophagy), may be beneficial in some circumstances.127 Upregulation of autophagy in response to chemotherapeutics may provide a survival response to cancer cells; thus, it may be of value to simultaneously block autophagy while treating with chemotherapeutics.174

At present, there are no known direct inhibitors of Atg proteins and the only intervention is the small interfering RNA-mediated knockdown of genes such as beclin1, Vps34 or Atg5, Atg10, and Atg12.175 A promising target for therapeutic intervention is Atg1. Atg1 is a serine–threonine protein kinase and is a major regulator of autophagy. Studies are underway to understand the signaling pathways regulating Atg1 and physiologically relevant targets of Atg1 kinase activity.176 Considerable efforts have been made to produce a small-molecule inhibitor of this kinase.

Enhancing autophagy could also be beneficial in the treatment of bacterial and viral infections through the increased clearance of intracellular pathogens and the processing of antigens for MHC class II presentation. Experiments in IL10-deficient mice have shown that stimulating autophagy by administration of the mTOR inhibitor, everolimus, attenuates chronic colitis.177 The immunosuppressive action of mTOR inhibitors, such as rapamycin and everolimus, limits their usefulness in the treatment of infectious diseases. Recently, compounds were screened for their abilities to enhance or suppress the growth-inhibitory effects of rapamycin in yeast.142 Three small-molecule enhancers of rapamycin (SMERs) were identified that are nontoxic and induce autophagy in mammalian cells. Interestingly, the SMERs seem to act independently of, or downstream of, mTOR as they did not result in a decrease in mTOR activity. All three SMERs were shown to enhance the clearance of mutant Huntingtin fragments and to protect against their toxicity in cell models and Drosophila.142 Two of the three compounds also show promise for enhancing the clearance of mycobacteria. Both of these SMERs reduced the numbers of intracellular mycobacteria in primary human macrophages.178 Thus, SMERs are an exciting development with potential for the treatment of both neurodegenerative and infectious diseases. However, attempts to manipulate autophagy for enhanced pathogen clearance may have unintentional effects—cellular components of the immune system, such as the Th2 cells, might be sensitive to cell-death induction through autophagy, with secondary implications of Th1–Th2 polarization on the regulation of autophagy.73, 107

In a recent study, sirolimus (rapamycin) was used to upregulate autophagy in a patient with severe refractory colonic and perianal CD.179 This is the first reported case of the use of sirolimus to treat CD, and there was a marked and sustained improvement in CD symptoms. In CD treatment, autophagy stimulation may be problematic in view of the other immunosuppressive therapy that patients are already exposed to. The prosurvival function of autophagy is generally believed to be adaptive, but, in the context of an increased risk of malignancy in IBD, this process could well be maladaptive.

Conclusion

Autophagy is involved in a wide range of medical conditions. Both genetic findings and functional experiments have kindled a great research interest in the therapeutic potential of manipulating the autophagic response, both nonselective (starvation induced) and selective autophagy (Table 2). We have summarized the increasing evidence implicating the autophagy machinery in the intracellular processing of microorganisms and in the presentation of epitopes to regulate the adaptive immune response.

In theory, the manipulation of the autophagic response offers an interesting novel treatment strategy. The balance between autophagy and apoptosis, particularly with regard to tumor survival, as well as in the regulation of the immune response, needs to be considered before translating these discoveries to patient treatment.

Disclosure

Johan Van Limbergen is funded by a Research Training Fellowship from Action Medical Research, The Gay–Ramsay–Steel–Maitland or Stafford Trust and the Hazel M Wood Charitable Trust. Craig Stevens was supported by a Cancer Research UK Programme Grant (C483/A6354). Elaine R Nimmo was supported by a Wellcome Trust Programme Grant (072789/Z/03/Z). David Wilson was the holder of a Medical Research Council strategic grant (cohorts initiative, Grant number G0800675). Financial assistance was also provided by Schering–Plough and the GI/Nutrition Research Fund, Child Life and Health, University of Edinburgh. We are indebted to the authors whose work could not be cited because of space restrictions.

References

Levine, B. & Deretic, V. Unveiling the roles of autophagy in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 767–777 (2007).

Xie, Z. & Klionsky, D.J. Autophagosome formation: core machinery and adaptations. Nat. Cell. Biol. 9, 1102–1109 (2007).

Kim, J., Huang, W-P., Stromhaug, P.E. & Klionsky, D.J. Convergence of multiple autophagy and cytoplasm to vacuole targeting components to a perivacuolar membrane compartment prior to de novo vesicle formation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 763–773 (2002).

Suzuki, K. The pre-autophagosomal structure organized by concerted functions of APG genes is essential for autophagosome formation. EMBO J. 20, 5971–5981 (2001).

Mizushima, N. Dissection of autophagosome formation using Apg5-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells. J. Cell Biol. 152, 657–668 (2001).

Mizushima, N. et al. Mouse Apg16L, a novel WD-repeat protein, targets to the autophagic isolation membrane with the Apg12-Apg5 conjugate. J. Cell Sci. 116, 1679–1688 (2003).

Kirisako, T. et al. Formation process of autophagosome is traced with Apg8/Aut7p in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 147, 435–446 (1999).

Itoh, T., Fujita, N., Kanno, E., Yamamoto, A., Yoshimori, T. & Fukuda, M. Golgi-resident small GTPase Rab33B interacts with Atg16L and modulates autophagosome formation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 19, 2916–2925 (2008).

Fujita, N., Itoh, T., Omori, H., Fukuda, M., Noda, T. & Yoshimori, T. The Atg16L complex specifies the site of LC3 lipidation for membrane biogenesis in autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2092–2100 (2008).

Delgado, M. et al. Autophagy and pattern recognition receptors in innate immunity. Immunol. Rev. 227, 189–202 (2009).

Kabeya, Y. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 19, 5720–5728 (2000).

Yorimitsu, T. & Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy: molecular machinery for self-eating. Cell Death Differ. 12 (Suppl 2), 1542–1552 (2005).

Klionsky, D.J. et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy 4, 151–175 (2008).

Mizushima, N. et al. A protein conjugation system essential for autophagy. Nature 395, 395–398 (1998).

Guan, J. et al. Cvt18/Gsa12 is required for cytoplasm-to-vacuole transport, pexophagy, and autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia pastoris. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 3821–3838 (2001).

Baba, M., Osumi, M., Scott, S.V., Klionsky, D.J. & Ohsumi, Y. Two distinct pathways for targeting proteins from the cytoplasm to the vacuole/lysosome. J. Cell Biol. 139, 1687–1695 (1997).

Ogawa, M., Yoshimori, T., Suzuki, T., Sagara, H., Mizushima, N. & Sasakawa, C. Escape of intracellular Shigella from autophagy. Science 307, 727–731 (2005).

Shintani, T., Huang, W.P., Stromhaug, P.E. & Klionsky, D.J. Mechanism of cargo selection in the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. Dev. Cell 3, 825–837 (2002).

Sanjuan, M.A. et al. Toll-like receptor signalling in macrophages links the autophagy pathway to phagocytosis. Nature 450, 1253–1257 (2007).

Pankiv, S. et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24131–24145 (2007).

Munz, C. Enhancing immunity through autophagy. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27; e-pub ahead of print 23 December 2008 (2009).

de Duve, C. & Wattiaux, R. Functions of lysosomes. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 28, 435–492 (1966).

Ashford, T.P. & Porter, K.R. Cytoplasmic components in hepatic cell lysosomes. J. Cell Biol. 12, 198–202 (1962).

Deter, R.L., Baudhuin, P. & de Duve, C. Participation of lysosomes in cellular autophagy induced in rat liver by glucagon. J. Cell Biol. 35, C11–C16 (1967).

Bolender, R.P. & Weibel, E.R. A morphometric study of the removal of phenobarbital-induced membranes from hepatocytes after cessation of treatment. J. Cell Biol. 56, 746–761 (1973).

Beaulaton, J. & Lockshin, R.A. Ultrastructural study of the normal degeneration of the intersegmental muscles of Anthereae polyphemus and Manduca sexta (Insecta, Lepidoptera) with particular reference of cellular autophagy. J. Morphol. 154, 39–57 (1977).

Veenhuis, M., Douma, A., Harder, W. & Osumi, M. Degradation and turnover of peroxisomes in the yeast Hansenula polymorpha induced by selective inactivation of peroxisomal enzymes. Arch. Microbiol. 134, 193–203 (1983).

Pfeifer, U. Inhibition by insulin of the physiological autophagic breakdown of cell organelles. Acta. Biol. Med. Ger. 36, 1691–1694 (1977).

Mortimore, G.E. & Schworer, C.M. Induction of autophagy by amino-acid deprivation in perfused rat liver. Nature 270, 174–176 (1977).

Seglen, P.O. & Gordon, P.B. 3-methyladenine: specific inhibitor of autophagic/lysosomal protein degradation in isolated rat hepatocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79, 1889–1892 (1982).

Holen, I., Gordon, P.B. & Seglen, P.O. Protein kinase-dependent effects of okadaic acid on hepatocytic autophagy and cytoskeletal integrity. Biochem. J. 284, 633–636 (1992).

Kang, C., You, Y.J. & Avery, L. Dual roles of autophagy in the survival of Caenorhabditis elegans during starvation. Genes Dev. 21, 2161–2171 (2007).

Kunz, J. Target of rapamycin in yeast, TOR2, is an essential phosphatidylinositol kinase homolog required for G1 progression. Cell 73, 585–596 (1993).

Blommaart, E.F., Luiken, J.J., Blommaart, P.J., van Woerkom, G.M. & Meijer, A.J. Phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 is inhibitory for autophagy in isolated rat hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2320–2326 (1995).

Noda, T. & Ohsumi, Y. Tor, a phosphatidylinositol kinase homologue, controls autophagy in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 3963–3966 (1998).

Wullschleger, S., Loewith, R. & Hall, M.N. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124, 471–484 (2006).

Proud, C.G. Signalling to translation: how signal transduction pathways control the protein synthetic machinery. Biochem. J. 403, 217–234 (2007).

Huang, J. & Manning, B.D. The TSC1–TSC2 complex: a molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem. J. 412, 179–190 (2008).

Kim, E., Goraksha-Hicks, P., Li, L., Neufeld, T.P. & Guan, K.L. Regulation of TORC1 by Rag GTPases in nutrient response. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 935–945 (2008)Advanced online publication.

Sancak, Y. et al. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science 320, 1496–1501 (2008).

Sancak, Y. et al. PRAS40 is an insulin-regulated inhibitor of the mTORC1 protein kinase. Mol. Cell 25, 903–915 (2007).

Ma, L., Chen, Z., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Tempst, P. & Pandolfi, P.P. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell 121, 179–193 (2005).

Gwinn, D.M. et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell 30, 214–226 (2008).

Reggiori, F. & Klionsky, D.J. Autophagosomes: biogenesis from scratch? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17, 415–422 (2005).

Young, A.R. et al. Starvation and ULK1-dependent cycling of mammalian Atg9 between the TGN and endosomes. J. Cell Sci. 119 (Part 18), 3888–3900 (2006).

Kamada, Y., Funakoshi, T., Shintani, T., Nagano, K., Ohsumi, M. & Ohsumi, Y. Tor-mediated induction of autophagy via an Apg1 protein kinase complex. J. Cell Biol. 150, 1507–1513 (2000).

Suzuki, K. & Ohsumi, Y. Molecular machinery of autophagosome formation in yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 581, 2156–2161 (2007).

Cheong, H., Nair, U., Geng, J. & Klionsky, D.J. The Atg1 kinase complex is involved in the regulation of protein recruitment to initiate sequestering vesicle formation for nonspecific autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 668–681 (2008).

Kawamata, T., Kamada, Y., Kabeya, Y., Sekito, T. & Ohsumi, Y. Organization of the pre-autophagosomal structure responsible for autophagosome formation. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2039–2050 (2008).

Hara, T. et al. FIP200, a ULK-interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 181, 497–510 (2008).

Byfield, M.P., Murray, J.T. & Backer, J.M. hVps34 is a nutrient-regulated lipid kinase required for activation of p70 S6 kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33076–33082 (2005).

Backer, J.M. The regulation and function of Class III PI3Ks: novel roles for Vps34. Biochem. J. 410, 1–17 (2008).

Liang, X.H. Protection against fatal Sindbis virus encephalitis by Beclin, a novel Bcl-2-interacting protein. J. Virol. 72, 8586–8596 (1998).

Levine, B., Sinha, S. & Kroemer, G. Bcl-2 family members: dual regulators of apoptosis and autophagy. Autophagy 4, 600–606 (2008).

Pattingre, S. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell 122, 927–939 (2005).

Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 931–937 (2007).

Scherz-Shouvai, R., Shvets, E., Fass, E., Shorer, H., Gil, L. & Elazar, Z. Reactive oxygen species are essential for autophagy and specifically regulate the activity of Atg4. EMBO J. 26, 1749–1760 (2007).

Meijer, A.J. & Codogno, P. Signalling and autophagy regulation in health and disease. Mol. Aspects Med. 27, 411–425 (2006).

Wei, Y., Pattingre, S., Sinha, S., Bassik, M. & Levine, B. JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 regulates starvation-induced autophagy. Mol. Cell 30, 678–688 (2008).

Sarkar, S. et al. Lithium induces autophagy by inhibiting inositol monophosphatase. J. Cell Biol. 170, 1101–1111 (2005).

Williams, A. et al. Novel targets for Huntington's disease in an mTOR-independent autophagy pathway. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 295–305 (2008).

Sarkar, S., Ravikumar, B., Floto, R.A. & Rubinsztein, D.C. Rapamycin and mTOR-independent autophagy inducers ameliorate toxicity of polyglutamine-expanded huntingtin and related proteinopathies. Cell Death. Differentiation. 16, 46–56 (2009).

Qing, G., Yan, P., Qu, Z., Liu, H. & Xiao, G. Hsp90 regulates processing of NF-kappaB2 p100 involving protection of NF-kappaB-inducing kinase (NIK) from autophagy-mediated degradation. Cell Res. 17, 520–530 (2007).

Qing, G., Yan, P. & Xiao, G. Hsp90 inhibition results in autophagy-mediated proteasome-independent degradation of IkappaB kinase (IKK). Cell Res. 16, 895–901 (2006).

Yu, L. et al. Autophagic programmed cell death by selective catalase degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 4952–4957 (2006).

Nakagawa, I. Autophagy defends cells against invading group A Streptococcus. Science 306, 1037–1040 (2004).

Rikihisa, Y. Glycogen autophagosomes in polymorphonuclear leukocytes induced by Rickettsiae. Anat. Rec. 208, 319–327 (1984).

Rich, K.A., Burkett, C. & Webster, P. Cytoplasmic bacteria can be targets for autophagy. Cell Microbiol. 5, 455–468 (2003).

Gutierrez, M.G., Master, S.S., Singh, S.B., Taylor, G.A., Colombo, M.I. & Deretic, V. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell 119, 753–766 (2004).

Birmingham, C.L., Smith, A.C., Bakowski, M.A., Yoshimori, T. & Brumell, J.H. Autophagy controls Salmonella infection in response to damage to the Salmonella-containing vacuole. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 11374–11383 (2006).

Ling, Y.M. Vacuolar and plasma membrane stripping and autophagic elimination of Toxoplasma gondii in primed effector macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2063–2071 (2006).

Alonso, S., Pethe, K., Russell, D.G. & Purdy, G.E. Lysosomal killing of mycobacterium mediated by ubiquitin-derived peptides is enhanced by autophagy. Proc. Ntl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 6031–6036 (2007).

Schmid, D. & Munz, C. Innate and adaptive immunity through autophagy. Immunity 27, 11–21 (2007).

Gutierrez, M.G. et al. Protective role of autophagy against Vibrio cholerae cytolysin, a pore-forming toxin from V. cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 1829–1834 (2007).

Saka, H.A., Gutierrez, M.G., Bocco, J.L. & Colombo, M.I. The autophagic pathway: a cell survival strategy against the bacterial pore-forming toxin Vibrio cholerae cytolysin. Autophagy 3, 363–365 (2007).