Abstract

Recently, ‘Liquid crystal display (LCD) vs. organic light-emitting diode (OLED) display: who wins?’ has become a topic of heated debate. In this review, we perform a systematic and comparative study of these two flat panel display technologies. First, we review recent advances in LCDs and OLEDs, including material development, device configuration and system integration. Next we analyze and compare their performances by six key display metrics: response time, contrast ratio, color gamut, lifetime, power efficiency, and panel flexibility. In this section, we focus on two key parameters: motion picture response time (MPRT) and ambient contrast ratio (ACR), which dramatically affect image quality in practical application scenarios. MPRT determines the image blur of a moving picture, and ACR governs the perceived image contrast under ambient lighting conditions. It is intriguing that LCD can achieve comparable or even slightly better MPRT and ACR than OLED, although its response time and contrast ratio are generally perceived to be much inferior to those of OLED. Finally, three future trends are highlighted, including high dynamic range, virtual reality/augmented reality and smart displays with versatile functions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Display technology has gradually but profoundly shaped the lifestyle of human beings, which is widely recognized as an indispensable part of the modern world1. Presently, liquid crystal displays (LCDs) are the dominant technology, with applications spanning smartphones, tablets, computer monitors, televisions (TVs), to data projectors2, 3, 4, 5. However, in recent years, the market for organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays has grown rapidly and has started to challenge LCDs in all applications, especially in the small-sized display market6, 7, 8. Lately, ‘LCD vs. OLED: who wins?’ has become a topic of heated debate9.

LCDs are non-emissive, and their invention can be traced back to the 1960s and early 1970s10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. With extensive material research and development, device innovation and heavy investment on advanced manufacturing technologies, thin-film transistor (TFT) LCD technology has gradually matured in all aspects; some key hurdles, such as the viewing angle, response time and color gamut, have been overcome5. Compared with OLEDs, LCDs have advantages in lifetime, cost, resolution density and peak brightness16. On the other hand, OLEDs are emissive; their inherent advantages are obvious, such as true black state, fast response time and an ultra-thin profile, which enables flexible displays8, 9. As for color performance, OLEDs have a wider color gamut over LCDs employing a white light-emitting diode (WLED) as a backlight. Nevertheless, LCD with a quantum dot (QD) backlight has been developed and promoted17, 18, 19, 20. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of green and red QDs is only 25 nm. As a result, a QD-enhanced LCD has a wider color gamut than an OLED. Generally speaking, both technologies have their own pros and cons. The competition is getting fierce; therefore, an objective systematic analysis and comparison on these two superb technologies is in great demand.

In this review paper, we present recent progress on LCDs and OLEDs regarding materials, device structures to final panel performances. First, in Section II, we briefly describe the device configurations and operation principles of these two technologies. Then, in Section III, we choose six key metrics: response time, contrast ratio, color gamut, lifetime, power efficiency, and panel flexibility, to evaluate LCDs and OLEDs. Their future perspectives are discussed in Section IV, including high dynamic range (HDR), virtual reality/augmented reality (VR/AR) and smart displays with versatile functions.

Device configurations and operation principles

Liquid crystal displays

Liquid crystal (LC) materials do not emit light; therefore, a backlight unit is usually needed (except in reflective displays) to illuminate the display panel. Figure 1 depicts an edge-lit TFT-LCD. The incident LED passes through the light-guide plate and multiple films and is then modulated by the LC layer sandwiched between two crossed polarizers5. In general, four popular LCD operation modes are used depending on the molecular alignments and electrode configurations: (1) twisted nematic (TN) mode, (2) vertical alignment (VA) mode, (3) in-plane switching (IPS) mode, and (4) fringe-field switching (FFS) mode13, 14, 15, 21. Below, we will briefly discuss each operation mode.

TN mode

The 90° TN mode was first published in 1971 by Schadt and Helfrich13. In the voltage-off state, the LC director twists 90° continually from the top to the bottom substrates (Figure 2a), introducing a so-called polarization rotation effect. As the voltage exceeds a threshold (Vth), the LC directors start to unwind and the polarization rotation effect gradually diminishes, leading to decreased transmittance. This TN mode has a high transmittance and low operation voltage (~5 Vrms), but its viewing angle is somewhat limited22. To improve the viewing angle and extend its applications to desktop computers and TVs, some specially designed compensation films, such as discotic film or Fuji film, are commonly used23, 24. Recently, Sharp developed a special micro-tube film to further widen the viewing angle and ambient contrast ratio (ACR) for TN LCDs25.

VA mode

VA was first invented in 1971 by Schiekel and Fahrenschon14 but did not receive widespread attention until the late 1990s, when multi-domain VA (MVA) mode was proposed to solve the viewing angle problem26, 27, 28. In the VA mode, an LC with a negative Δɛ<0 is used and the electric field is in the longitudinal direction. In the initial state (V=0), the LC directors are aligned in the vertical direction (Figure 2b). As the voltage exceeds a threshold, the LC directors are gradually tilted so that the incident light transmits through the crossed polarizers. Film-compensated MVA mode has a high on-axis contrast ratio (CR; >5000:1), wide viewing angle and fairly fast response time (5 ms). Thus it is widely used in large TVs29, 30. Recently, curved MVA LCD TVs have become popular because VA mode enables the smallest bending curvature compared with other LCDs31, 32.

IPS mode

IPS mode was first proposed in 1973 by Soref15 but remained a scientific curiosity until the mid-1990s owing to the demand of touch panels33, 34. In an IPS cell, the LC directors are homogeneously aligned and the electric fields are in the lateral direction (Figure 2c). As the voltage increases, the strong in-plane fringing electric fields between the interdigital electrodes reorient the LC directors. Such a unique mechanism makes IPS a favorable candidate for touch panels because no ripple effect occurs upon touching the panel. However, the peak transmittance of IPS is relatively low (~75%) because the LC molecules above the electrodes cannot be effectively reoriented. This low transmittance region is called a dead zone5.

FFS mode

FFS mode was proposed in 1998 by three Korean scientists: SH Lee, SL Lee, and HY Kim21. Soon after its invention, FFS became a popular LCD mode due to its outstanding features, including high transmittance, wide viewing angle, weak color shift, built-in storage capacitance, and robustness to touch pressure35, 36, 37. Basically, FFS shares a similar working principle with IPS, but the pixel and common electrodes are separated by a thin passivation layer (Figure 2d). As a result, the electrode width and gap are able to be much smaller than those of IPS, leading to much stronger fringe fields covering both the electrode and gap regions. Thus the dead zone areas are reduced. In general, both positive (p-FFS) and negative (n-FFS) Δɛ LCs can be used in the FFS mode38, 39. Currently, n-FFS is preferred for mobile applications because its transmittance is higher than that of p-FFS (98 vs. 88%)40.

As summarized in Table 1, these four LCD modes have their own unique features and are used for different applications. For example, TN has the advantages of low cost and high optical efficiency; thus, it is mostly used in wristwatches, signage and laptop computers, for which a wide view is not absolutely necessary. MVA mode is particularly attractive for large TVs because a fast response time, high CR and wide viewing angle are required to display motion pictures. On the other hand, IPS and FFS modes are used in mobile displays, where low power consumption for a long battery life and pressure resistance for touch screens are critical.

Organic light-emitting diode

The basic structure of an OLED display, proposed by Tang and VanSlyke41 in 1987, consists of organic stacks sandwiched between anode and cathode, as shown in Figure 3a. Electrons and holes are injected from electrodes to organic layers for recombination and light emission; hence, an OLED display is an emissive display, unlike an LCD. Currently, multi-layer structures in OLEDs with different functional materials are commonly used, as shown in Figure 3b. The emitting layer (EML), which is used for light emission, consists of dopant and host materials with high quantum efficiency and high carrier mobility. Hole-transporting layer (HTL) and electron-transporting layer (ETL) between the EML and electrodes bring carriers into the EML for recombination. Hole- and electron-injection layers (HIL and EIL) are inserted between the electrodes and the HTL and ETL interface to facilitate carrier injection from the conductors to the organic layers. When applying voltage to the OLED, electrons and holes supplied from the cathode and anode, respectively, transport to the EML for recombination to give light.

Generally, each layer in an OLED is quite thin, and the total thickness of the whole device is <1 μm (substrates are not included). Thus the OLED is a perfect candidate for flexible displays. For an intrinsic organic material, its carrier mobility (<0.1 cm2 Vs−1) and free carrier concentration (1010 cm−3) are fairly low, limiting the device efficiency. Thus doping technology is commonly used42, 43. Additionally, to generate white light, two configurations can be considered: (1) patterned red, green and blue (RGB) OLEDs; and (2) a white OLED with RGB color filters (CFs). Both have pros and cons. In general, RGB OLEDs are mostly used for small-sized mobile displays, while white OLEDs with CFs are used for large TVs.

The EML is the core of an OLED. Based on the emitters inside, OLED devices can be categorized into four types: fluorescence, triplet-triplet fluorescence (TTF), phosphorescence, and thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF)41, 44, 45, 46, 47.

Fluorescent OLED

First, upon electrical excitation, 25% singlets and 75% triplets are formed with higher and lower energy, respectively. In a fluorescent OLED, only singlets decay radiatively through fluorescence with an ~ns exciton lifetime, which sets the theoretical limit of the internal quantum efficiency (IQE) to 25%, as shown in Figure 4a.

Triplet-triplet fluorescent OLED

Two triplet excitons may fuse to form one singlet exciton through the so-called triplet fusion process, as shown in Figure 4b, and relaxes to the energy from the singlet state, called TTF, which improves the theoretical limit of the IQE to 62.5%.

Phosphorescent OLED

With the introduction of heavy metal atoms (such as Ir and Pt) into the emitters, strong spin-orbital coupling greatly reduces the triplet lifetime to ~μs, which results in efficient phosphorescent emission. The singlet exciton experiences intersystem crossing to the triplet state for light emission, achieving a 100% IQE, as shown in Figure 4c. Owing to the long radiative lifetime (~μs) in a phosphorescent OLED, the triplet may interact with another triplet and polaron (triplet-triplet annihilation and triplet-polaron annihilation, respectively), which results in efficiency roll-off under high current driving48. Such processes may create hot excitons and hot polarons to shorten the operation lifetime, especially for blue-emitting devices, as will be discussed in the next section49.

Thermally activated delayed fluorescent OLED

The energy between the singlet and triplet can be reduced (<0.1 eV) by minimizing the exchange energy50; thus the triplet can jump back to the singlet state by means of thermal energy (reverse intersystem crossing) for fluorescence emission, which is called TADF, as shown in Figure 4d. Achieving a 100% IQE is possible for TADF emission without a heavy atom in the organic material, which reduces the material cost and is more flexible for organic molecular design.

In practical applications, red and green phosphorescent emitters are the mainstream for active matrix (AM) OLEDs due to their high IQE. While, for blue emitters, TTF is mostly used because of its longer operation lifetime51. However, recently, TADF materials have been rapidly emerging and are expected to have widespread applications in the near future.

It is worth mentioning that, although IQE could be as high as 100% in theory, due to the refractive index difference the emission generated inside the OLED experiences total internal reflection, which reduces the extraction efficiency. Taking a bottom emission OLED with a glass substrate (n~1.5) and an indium-tin-oxide anode (n~1.8) as an example, the final extraction efficiency is only ~20%52.

Display metrics

To evaluate the performance of display devices, several metrics are commonly used, such as response time, CR, color gamut, panel flexibility, viewing angle, resolution density, peak brightness, lifetime, among others. Here we compare LCD and OLED devices based on these metrics one by one.

Response time and motion picture response time

A fast response time helps to mitigate motion image blur and boost the optical efficiency, but this statement is only qualitatively correct. When quantifying the visual performance of a moving object, motion picture response time (MPRT) is more representative, and the following equation should be used53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58:

where Tf is the frame time (e.g., Tf=16.67 ms for 60 fps). Using this equation, we can easily obtain an MPRT as long as the LC response time and TFT frame rate are known. The results are plotted in Figure 5.

From Figure 5, we can gain several important physical insights: (1) Increasing the frame rate is a simple approach to suppress image motion blur, but its improvement gradually saturates. For example, if the LC response time is 10 ms, then increasing the frame rate from 30 to 60 fps would significantly reduce the MPRT. However, as the TFT frame rate continues to increase to 120 and 240 fps, then the improvement gradually saturates. (2) At a given frame rate, say 120 fps, as the LC response time decreases, the MPRT decreases almost linearly and then saturates. This means that the MPRT is mainly determined by the TFT frame rate once the LC response time is fast enough, i.e., τ≪Tf. Under such conditions, Equation (1) is reduced to MPRT≈0.8Tf. (3) When the LC response is <2 ms, its MPRT is comparable to that of an OLED at the same frame rate, e.g., 120 fps. Here we assume the OLED’s response time is 0.

The last finding is somehow counter to the intuition that a LCD should have a more severe motion picture image blur, as its response time is approximately 1000 × slower than that of an OLED (ms vs. μs). To validate this prediction, Chen et al.58 performed an experiment using an ultra-low viscosity LC mixture in a commercial VA test cell. The measured average gray-to-gray response time is 1.29 ms by applying a commonly used overdrive and undershoot voltage method. The corresponding average MPRT at 120 fps is 6.88 ms, while that of an OLED is 6.66 ms. These two results are indeed comparable. If the frame rate is doubled to 240 fps, both LCDs and OLEDs show a much faster but still similar MPRT values (3.71 vs. 3.34 ms). Thus the above finding is confirmed experimentally.

If we want to further suppress image blur to an unnoticeable level (MPRT<2 ms), decreasing the duty ratio (for LCDs, this is the on-time ratio of the backlight, called scanning backlight or blinking backlight) is mostly adopted59, 60, 61. However, the tradeoff is reduced brightness. To compensate for the decreased brightness due to the lower duty ratio, we can boost the LED backlight brightness. For OLEDs, we can increase the driving current, but the penalties are a shortened lifetime and efficiency roll-off62, 63, 64.

CR and ACR

High CR is a critical requirement for achieving supreme image quality. OLEDs are emissive, so, in theory, their CR could approach infinity to one. However, this is true only under dark ambient conditions. In most cases, ambient light is inevitable. Therefore, for practical applications, a more meaningful parameter, called the ACR, should be considered65, 66, 67, 68:

where Ton (Toff) represents the on-state (off-state) brightness of an LCD or OLED and A is the intensity of reflected light by the display device.

As Figure 6 depicts, there are two types of surface reflections. The first one is from a direct light source, i.e., the sun or a light bulb, denoted as A1. Its reflection is fairly specular, and in practice, we can avoid this reflection (i.e., strong glare from direct sun) by simply adjusting the display position or viewing direction. However, the second reflection, denoted as A2, is quite difficult to avoid. It comes from an extended background light source, such as a clear sky or scattered ceiling light. In our analysis, we mainly focus on the second reflection (A2).

To investigate the ACR, we have to clarify the reflectance first. A large TV is often operated by remote control, so touchscreen functionality is not required. As a result, an anti-reflection coating is commonly adopted. Let us assume that the reflectance is 1.2% for both LCD and OLED TVs. For the peak brightness and CR, different TV makers have their own specifications. Here, without losing generality, let us use the following brands as examples for comparison: LCD peak brightness=1200 nits, LCD CR=5000:1 (Sony 75″ X940E LCD TV); OLED peak brightness=600 nits, and OLED CR=infinity (Sony 77″ A1E OLED TV). The obtained ACR for both LCD and OLED TVs is plotted in Figure 7a. As expected, OLEDs have a much higher ACR in the low illuminance region (dark room) but drop sharply as ambient light gets brighter. At 63 lux, OLEDs have the same ACR as LCDs. Beyond 63 lux, LCDs take over. In many countries, 60 lux is the typical lighting condition in a family living room. This implies that LCDs have a higher ACR when the ambient light is brighter than 60 lux, such as in office lighting (320–500 lux) and a living room with the window shades or curtain open. Please note that, in our simulation, we used the real peak brightness of LCDs (1200 nits) and OLEDs (600 nits). In most cases, the displayed contents could vary from black to white. If we consider a typical 50% average picture level (i.e., 600 nits for LCDs vs. 300 nits for OLEDs), then the crossover point drops to 31 lux (not shown here), and LCDs are even more favorable. This is because the on-state brightness plays an important role to the ACR, as Equation (2) shows.

Calculated ACR as a function of different ambient light conditions for LCD and OLED TVs. Here we assume that the LCD peak brightness is 1200 nits and OLED peak brightness is 600 nits, with a surface reflectance of 1.2% for both the LCD and OLED. (a) LCD CR: 5000:1, OLED CR: infinity; (b) LCD CR: 20 000:1, OLED CR: infinity.

Recently, an LCD panel with an in-cell polarizer was proposed to decouple the depolarization effect of the LC layer and color filters69. Thus the light leakage was able to be suppressed substantially, leading to a significantly enhanced CR. It has been reported that the CR of a VA LCD could be boosted to 20 000:1. Then we recalculated the ACR, and the results are shown in Figure 7b. Now, the crossover point takes place at 16 lux, which continues to favor LCDs.

For mobile displays, such as smartphones, touch functionality is required. Thus the outer surface is often subject to fingerprints, grease and other contaminants. Therefore, only a simple grade AR coating is used, and the total surface reflectance amounts to ~4.4%. Let us use the FFS LCD as an example for comparison with an OLED. The following parameters are used in our simulations: the LCD peak brightness is 600 nits and CR is 2000:1, while the OLED peak brightness is 500 nits and CR is infinity. Figure 8a depicts the calculated results, where the intersection occurs at 107 lux, which corresponds to a very dark overcast day. If the newly proposed structure with an in-cell polarizer is used, the FFS LCD could attain a 3000:1 CR69. In that case, the intersection is decreased to 72 lux (Figure 8b), corresponding to an office building hallway or restroom lighting. For reference, a typical office light is in the range of 320–500 lux70. As Figure 8 depicts, OLEDs have a superior ACR under dark ambient conditions, but this advantage gradually diminishes as the ambient light increases. This was indeed experimentally confirmed by LG Display71. Display brightness and surface reflection have key roles in the sunlight readability of a display device.

Color gamut

Vivid color is another critical requirement of all display devices72. Until now, several color standards have been proposed to evaluate color performance, including sRGB, NTSC, DCI-P3 and Rec. 202073, 74, 75, 76. It is believed that Rec. 2020 is the ultimate goal, and its coverage area in color space is the largest, nearly twice as wide as that of sRGB. However, at the present time, only RGB lasers can achieve this goal.

For conventional LCDs employing a WLED backlight, the yellow spectrum generated by YAG (yttrium aluminum garnet) phosphor is too broad to become highly saturated RGB primary colors, as shown in Figure 9a77. As a result, the color gamut is only ~50% Rec. 2020. To improve the color gamut, more advanced backlight units have been developed, as summarized in Table 2. The first choice is the RG-phosphor-converted WLED78, 79. From Figure 9b, the red and green emission spectra are well separated; still, the green spectrum (generated by β-sialon:Eu2+ phosphor) is fairly broad and red spectrum (generated by K2SiF6:Mn4+ (potassium silicofluoride, KSF) phosphor) is not deep enough, leading to 70%–80% Rec. 2020, depending on the color filters used.

A QD-enhanced backlight (e.g., quantum dot enhancement film, QDEF) offers another option for a wide color gamut20, 80, 81. QDs exhibit a much narrower bandwidth (FWHM~20–30 nm) (Figure 9c), so that high purity RGB colors can be realized and a color gamut of ~90% Rec. 2020 can be achieved. One safety concern is that some high-performance QDs contain the heavy metal Cd. To be compatible with the restriction of hazardous substances, the maximum cadmium content should be under 100 ppm in any consumer electronic product82. Some heavy-metal-free QDs, such as InP, have been developed and used in commercial products83, 84, 85.

Recently, a new LED technology, called the Vivid Color LED, was demonstrated86. Its FWHM is only 10 nm (Figure 9d), which leads to an unprecedented color gamut (~98% Rec. 2020) together with specially designed color filters. Such a color gamut is comparable to that of laser-lit displays but without laser speckles. Moreover, the Vivid Color LED is heavy-metal free and shows good thermal stability. If the efficiency and cost can be further improved, it would be a perfect candidate for an LCD backlight.

The color performance of a RGB OLED is mainly governed by the three independent RGB EMLs. Currently, both deep blue fluorescent OLEDs87 and deep red phosphorescent OLEDs88 have been developed. The corresponding color gamut is >90% Rec. 2020. Apart from material development89, the color gamut of OLEDs could also be enhanced by device optimization. For example, a strong cavity could be formed between a semitransparent and reflective layer. This selects certain emission wavelengths and hence reduces the FWHM90. However, the tradeoff is increased color shift at large viewing angles91.

A color filter array is another effective approach to enhance the color gamut of an OLED. For example, in 2017, AUO demonstrated a 5-inch top-emission OLED panel with 95% Rec. 2020. In this design, so-called symmetric panel stacking with a color filter is employed to generate purer RGB primary colors92. Similarly, SEL developed a tandem white top-emitting OLED with color filters to achieve a high color gamut (96% Rec. 2020) and high resolution density (664 pixels per inch (ppi) simultaneously93.

Lifetime

As mentioned earlier, TFT LCDs are a fairly mature technology. They can be operated for >10 years without noticeable performance degradation. However, OLEDs are more sensitive to moisture and oxygen than LCDs. Thus their lifetime, especially for blue OLEDs, is still an issue. For mobile displays, this is not a critical issue because the expected usage of a smartphone is approximately 2–3 years. However, for large TVs, a lifetime of >30 000 h (>10 years) has become the normal expectation for consumers.

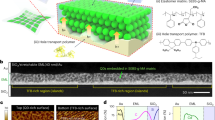

Here we focus on two types of lifetime: storage and operational. To enable a 10-year storage lifetime, according to the analysis94, the water vapor permeation rate and oxygen transmission rate for an OLED display should be <1 × 10−6 g (m2-day)−1 and 1 × 10−5 cm3 (m2-day)−1, respectively. To achieve these values, organic and/or inorganic thin films have been developed to effectively protect the OLED and lengthen its storage lifetime. Meanwhile, it is compatible to flexible substrates and favors a thinner display profile95, 96, 97.

The next type of lifetime is operational lifetime. Owing to material degradation, OLED luminance will decrease and voltage will increase after long-term driving98. For red, yellow and green phosphorescent OLEDs, their lifetime values at 50% luminance decrease (T50) can be as long as >80 000 h with a 1000 cd m−2 luminance99, 100, 101. Nevertheless, the operational lifetime of the blue phosphor is far from satisfactory. Owing to the long exciton lifetime (~μs) and wide bandgap (~3 eV), triplet-polaron annihilation occurs in the blue phosphorescent OLED, which generates hot polarons (~6 eV; this energy is higher than some bond energies, e.g., 3.04 eV for the C-N single bond), leading to a short lifetime. To improve its lifetime, several approaches have been proposed, such as designing a suitable device structure to broaden the recombination zone, stacking two or three OLEDs or introducing an exciton quenching layer. The operation lifetime of a blue phosphorescent OLED can be improved to 3700 h (T50, half lifetime) with an initial luminance of 1000 nits. However, this is still ~20 × shorter than that of red and green phosphorescent OLEDs101, 102, 103.

To further enhance the lifetime of the blue OLED, the NTU group has developed new ETL and TTF-EML materials together with an optimized layer structure and double EML structure104. Figure 10a shows the luminance decay curves of such a blue OLED under different initial luminance values (5000, 10 000, and 15 000 nits). From Figure 10b, the estimated T50 at 1000 nits of this blue OLED is ~56 000 h (~6–7 years)104, 105. As new materials and novel device structures continue to advance, the lifetime of OLEDs will be gradually improved.

Power efficiency

Power consumption is equally important as other metrics. For LCDs, power consumption consists of two parts: the backlight and driving electronics. The ratio between these two depends on the display size and resolution density. For a 55″ 4K LCD TV, the backlight occupies approximately 90% of the total power consumption. To make full use of the backlight, a dual brightness enhancement film is commonly embedded to recycle mismatched polarized light106. The total efficiency could be improved by ~60%.

The power efficiency of an OLED is generally limited by the extraction efficiency (ηext~20%). To improve the power efficiency, multiple approaches can be used, such as a microlens array, a corrugated structure with a high refractive index substrate107, replacing the metal electrode (such as the Al cathode) with a transparent metal oxide108, increasing the distance from the emission dipole to the metal electrode109 or increasing the carrier concentration by material optimizations110. Experimentally, external quantum efficiencies as high as 63% have been demonstrated107, 108. Note that sometimes the light-extraction techniques result in haze and image blur, which deteriorate the ACR and display sharpness111, 112, 113. Additionally, fabrication complexity and production yield are two additional concerns. Figure 11 shows the power efficiencies of white, green, red and blue phosphorescent as well as blue fluorescent/TTF OLEDs over time. For OLEDs with fluorescent emitters in the 1980s and 1990s, the power efficiency was limited by the IQE, typically <10 lm W−1(Refs. 41, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118). With the incorporation of phosphorescent emitters in the ~2000 s, the power efficiency was significantly improved owing to the materials and device engineering45, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125. The photonic design of OLEDs with regard to the light extraction efficiency was taken into consideration for further enchantment of the power efficiency126, 127, 128, 129, 130. For a green OLED, a power efficiency of 290 lm W−1 was demonstrated in 2011 (Ref. 127), which showed a >100 × improvement compared with that of the basic two-layer device proposed in 1987 (1.5 lm W−1 in Ref. 41). A white OLED with a power efficiency >100 lm W−1 was also demonstrated, which was comparable to the power efficiency of a LCD backlight. For red and blue OLEDs, their power efficiencies are generally lower than that of the green OLED due to their lower photopic sensitivity function, and there is a tradeoff between color saturation and power efficiency. Note, we separated the performances of blue phosphorescent and fluorescent/TTF OLEDs. For the blue phosphorescent OLEDs, although the power efficiency can be as high as ~80 lm W−1, the operation lifetime is short and color is sky-blue. For display applications, the blue TTF OLED is the favored choice, with an acceptable lifetime and color but a much lower power efficiency (16 lm W−1) than its phosphorescent counterpart131, 132. Overall, over the past three decades (1987–2017), the power efficiency of OLEDs has improved dramatically, as Figure 11 shows.

To compare the power consumption of LCDs and OLEDs with the same resolution density, the displayed contents should be considered as well. In general, OLEDs are more efficient than LCDs for displaying dark images because black pixels consume little power for an emissive display, while LCDs are more efficient than OLEDs at displaying bright images. Currently, a ~65% average picture level is the intersection point between RGB OLEDs and LCDs134. For color-filter-based white OLED TVs, this intersection point drops to ~30%. As both technologies continue to advance, the crossover point will undoubtedly change with time.

Panel flexibility

Flexible displays have a long history and have been attempted by many companies, but this technology has only recently begun to see commercial implementations for consumer electronics135. A good example is Samsung’s flagship smartphone, the Galaxy S series, which has an OLED display panel that covers the edge of the phone. However, strictly speaking, it is a curved display rather than a flexible display. One step forward, a foldable AM-OLED has been demonstrated with the curvature radius of 2 mm for 100 000 repeated folds136. Owing to the superior flexibility of the organic materials, a rollable AM-OLED display driven by an organic TFT was fabricated137. By replacing the brittle indium-tin-oxide with a flexible Ag nanowire as the anode, a stretchable OLED for up to a 120% strain was demonstrated138.

LCDs have limited flexibility. A curved TV is practical but going beyond that is rather difficult with rigid and thick glass substrates139. Fortunately, this obstacle has been removed with the implementation of a thin plastic substrate140, 141, 142. In 2017, a 12.1″ rollable LCD using organic TFT, called OLCD, was demonstrated, and its radius of curvature is 60 mm143. To maintain a uniform cell gap, a polymer wall was formed within the LC layer144. Additionally, it is reported that LCDs could be foldable with a segmented backlight. This is a good choice, but until now, no demo or real device has been demonstrated. Combining two bezel-less LCDs together is another solution to enable a foldable display, but this technology is still under development145.

Others

In addition to the aforementioned six display metrics, other parameters are equally important. For example, high-resolution density has become a standard for all high-end display devices. Currently, LCD is taking the lead in consumer electronic products. Eight-hundred ppi or even >1000 ppi LCDs have already been demonstrated and commercialized, such as in the Sony 5.5″ 4k Smartphone Xperia Z5 Premium. The resolution of RGB OLEDs is limited by the physical dimension of the fine-pitch shadow mask. To compete with LCDs, most OLED displays use the PenTile RGB subpixel matrix scheme146. The effective resolution density of an RGB OLED mobile display is~500 ppi. In the PenTile configuration, the blue subpixel has a larger size than the green and red subpixels. Thus a lower current is needed to achieve the required brightness, which is helpful for improving the lifetime of the blue OLED. On the other hand, owing to the lower efficiency of the blue TTF OLED compared with the red and green phosphorescent ones, this results in higher power consumption. To further enhance the resolution density, multiple approaches have been developed, as will be discussed later.

The viewing angle is another important property that defines the viewing experience at large oblique angles, which is quite critical for multi-viewer applications. OLEDs are self-emissive and have an angular distribution that is much broader than that of LCDs. For instance, at a 30° viewing angle, the OLED brightness only decreases by 30%, whereas the LCD brightness decrease exceeds 50%. To widen an LCD’s viewing angle, three options can be used. (1) Remove the brightness-enhancement film in the backlight system. The tradeoff is decreased on-axis brightness147. (2) Use a directional backlight with a front diffuser148, 149. Such a configuration enables excellent image quality regardless of viewing angle; however, image blur induced by a strong diffuser should be carefully treated. (3) Use QD arrays as the color filters20, 150, 151, 152. This design produces an isotropic viewing cone and high-purity RGB colors. However, preventing ambient light excitation of QDs remains a technical challenge20.

In addition to brightness, color, grayscale and the CR also vary with the viewing angle, known as color shift and gamma shift. In these aspects, LCDs and OLEDs have different mechanisms. For LCDs, they are induced by the anisotropic property of the LC material, which could be compensated for with uniaxial or biaxial films5. For OLEDs, they are caused by the cavity effect and color-mixing effect153, 154. With extensive efforts and development, both technologies have fairly mature solutions; currently, color shift and gamma shift have been minimized at large oblique angles.

Cost is another key factor for consumers. LCDs have been the topic of extensive investigation and investment, whereas OLED technology is emerging and its fabrication yield and capability are still far behind LCDs. As a result, the price of OLEDs is about twice as high as that of LCDs, especially for large displays. As more investment is made in OLEDs and more advanced fabrication technology is developed, such as ink-jet printing155, 156, 157, their price should decrease noticeably in the near future.

Future perspectives

Currently, both LCDs and OLEDs are commercialized and compete with each other in almost every display segment. They are basically two different technologies (non-emissive vs. emissive), but as a display, they share quite similar perspectives in the near future. Here we will focus on three aspects: HDR, VR/AR and smart displays with versatile functions.

High dynamic range

HDR is an emerging technology that can significantly improve picture quality158, 159, 160. However, strictly speaking, HDR is not a single metric; instead, it is more like a technical standard or a format (e.g., HDR10, Dolby Vision, etc.), unifying the aforementioned metrics. In general, HDR requires a higher CR (CR≥100 000:1), deeper dark state, higher peak brightness, richer grayscale (≥10 bits) and more vivid color.

Both LCD and OLED are HDR-compatible. Currently, the best HDR LCDs can produce brighter highlights than OLEDs, but OLEDs have better overall CRs thanks to their superior black level. To enhance an LCD’s CR, a local dimming backlight is commonly used, but its dimming accuracy is limited by the number of LED segmentations161, 162, 163. Recently, a dual-panel LCD system was proposed for pixel-by-pixel local dimming164, 165. In an experiment, an exceedingly high CR (>1 000 000:1) and high bit-depth (>14 bits) were realized at merely 5 volts. In 2017, such a dual-panel LCD was demonstrated by Panasonic, aiming at medical and vehicular applications. At 2018 consumer electronics show, Innolux demonstrated a 10.1″ LCD with an active matrix mini-LED backlight. The size of each mini-LED is 1 mm and pitch length is 2 mm. In total, there are 6720 local dimming zones. Such a mini-LED based LCD offers several attractive features: CR>1 000 000:1, peak brightness=1500 nits, HDR: 10-bit mini-LED and 8-bit LCD, and thin profile.

Also worth mentioning here is ultra-high brightness. Mostly, people pay more attention to the required high CR (CR>100 000:1) of HDR but fail to notice that CR is jointly determined by the dark state and peak brightness. For example, a 12-bit Perceptual Quantizer curve is generated for a range up to 10 000 nits, which is far beyond what current displays can provide166, 167.

The peak brightness of LCDs could be boosted to 2000 nits or even higher by simply using a high-power backlight. OLEDs are self-emissive, so their peak brightness would trade with lifetime. As a result, more advanced OLED materials and novel structural designs are highly desirable in the future. Another reason to boost peak brightness is to increase sunlight readability. Especially for some outdoor applications, such as public displays, peak brightness is critical to ensure good readability under strong ambient light. As discussed in the section of ‘CR and ACR’, high brightness leads to a high ACR, except that the power consumption will increase.

Virtual reality and augmented reality

Immersive VR/AR are two emerging wearable display technologies with great potential in entertainment, education, training, design, advertisement and medical diagnostics. However, new opportunities arise along with new challenges. VR head-mounted displays require a resolution density as high as >2000 ppi to eliminate the so-called screen door effect and generate more realistic immersive experiences.

An LCD’s resolution density is determined by the TFTs and color filter arrays. In SID 2017, Samsung demonstrated an LCD panel with a resolution of 2250 ppi for VR applications. The pitches of the sub-pixel and pixel are 3.76 and 11.28 μm, respectively. Meanwhile, field sequential color provides another promising option to triple the LCD resolution density168, 169. However, more advanced LC mixtures and fast response LCD modes are needed to suppress the color breakup issue170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179. For OLED microdisplays, eMagin proposed a novel direct patterning approach to enable 2645 ppi RGB organic emitters on a CMOS backplane180. Similar performance has been obtained by Sony. They developed a 0.5-inch AM-OLED panel with 3200 ppi using well-controlled color filter arrays181.

As for AR applications, lightweight, low power and high brightness are mainly determined by the display components. LC on silicon can generate high brightness182, but its profile is too bulky and heavy with the implementation of a polarization beam splitter. Removing the polarization beam splitter with a front light guide would be the appropriate solution183. However, integrating RGB LEDs with this light guide remains a significant challenge. Additionally, RGB LEDs, especially green LEDs, are not efficient enough. OLEDs have thin profiles, but their peak brightness and power efficiency are still far from satisfactory, especially for such AR devices, as they are mostly used outdoors, meaning high brightness is commonly required to increase the ACR of displayed images.

Smart displays with versatile functions

Currently, displays are no longer limited to traditional usages, such as TVs, pads or smartphones. Instead, they have become more diversified and are used in smart windows, smart mirrors, smart fridges, smart vending machines and so on. They have entered all aspects of our daily lives.

As these new applications are emerging, LCDs and OLEDs have new opportunities as well as new challenges. Let us take a vehicle display as an example: high brightness, good sunlight readability, and a wide working temperature range are required184. To follow this trend, LC mixtures with an ultra-high clearing temperature (>140 °C) have been recently developed, ensuring that the LCD works properly even at some extreme temperatures185. OLEDs have an attractive form factor for vehicle displays, but their performance needs to qualify under the abovementioned harsh working conditions. Similarly, for transparent displays or mirror displays, LCDs and OLEDs have their own merits and demerits186, 187, 188, 189. They should aim at versatile functions based on their own strengths.

Conclusion

We have briefly reviewed the recent progress of LCD and OLED technologies. Each technology has its own pros and cons. For example, LCDs are leading in lifetime, cost, resolution density and peak brightness; are comparable to OLEDs in ACR, viewing angle, power consumption and color gamut (with QD-based backlights); and are inferior to OLED in black state, panel flexibility and response time. Two concepts are elucidated in detail: the motion picture response time and ACR. It has been demonstrated that LCDs can achieve comparable image motion blur to OLEDs, although their response time is 1000 × slower than that of OLEDs (ms vs. μs). In terms of the ACR, our study shows that LCDs have a comparable or even better ACR than OLEDs if the ambient illuminance is >50 lux, even if its static CR is only 5000:1. The main reason is the higher brightness of LCDs. New trends for LCDs and OLEDs are also highlighted, including ultra-high peak brightness for HDR, ultra-high-resolution density for VR, ultra-low power consumption for AR and ultra-versatile functionality for vehicle display, transparent display and mirror display applications. The competition between LCDs and OLEDs is still ongoing. We believe these two TFT-based display technologies will coexist for a long time.

References

Castellano JA . Handbook of Display Technology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2012.

Chigrinov VG . Liquid Crystal Devices: Physics and Applications. Boston, MA, USA: Artech House; 1999.

Schadt M . Milestone in the history of field-effect liquid crystal displays and materials. Jpn J Appl Phys 2009; 48: 03B001.

Yeh P, Gu C . Optics of Liquid Crystal Displays. New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2010.

Yang DK, Wu ST . Fundamentals of Liquid Crystal Devices. 2nd edn. New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2014.

Geffroy B, Le Roy P, Prat C . Organic light‐emitting diode (OLED) technology: materials, devices and display technologies. Polym Int 2006; 55: 572–582.

Buckley A . Organic Light-Emitting Diodes (OLEDs): Materials, Devices and Applications. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2013.

Tsujimura T . OLED Display: Fundamentals and Applications 2nd edn.Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2017.

Barnes D . LCD or OLED: who wins? SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2013; 44: 26–27.

Heilmeier GH, Zanoni LA, Barton LA . Dynamic scattering: A new electrooptic effect in certain classes of nematic liquid crystals. Proc IEEE 1968; 56: 1162–1171.

Heilmeier GH, Zanoni LA, Barton LA . Dynamic scattering in nematic liquid crystals. Appl Phys Lett 1968; 13: 46–47.

Heilmeier GH, Zanoni LA, Barton LA . Further studies of the dynamic scattering mode in nematic liquid crystals. IEEE Trans Electron Dev 1970; 17: 22–26.

Schadt M, Helfrich W . Voltage‐dependent optical activity of a twisted nematic liquid crystal. Appl Phys Lett 1971; 18: 127–128.

Schiekel MF, Fahrenschon K . Deformation of nematic liquid crystals with vertical orientation in electrical fields. Appl Phys Lett 1971; 19: 391–393.

Soref RA . Transverse field effects in nematic liquid crystals. Appl Phys Lett 1973; 22: 165–166.

Lee JH, Liu DN, Wu ST . Introduction to Flat Panel Displays. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

Chen J, Hardev V, Hartlove J, Hofler J, Lee E . A high-efficiency wide-color-gamut solid-state backlight system for LCDs using quantum dot enhancement film. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2012; 43: 895–896.

Bourzac K . Quantum dots go on display: adoption by TV makers could expand the market for light-emitting nanocrystals. Nature 2013; 493: 283.

Luo ZY, Chen Y, Wu ST . Wide color gamut LCD with a quantum dot backlight. Opt Express 2013; 21: 26269–26284.

Chen HW, He J, Wu ST . Recent advances on quantum-dot-enhanced liquid-crystal displays. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron 2017; 23: 1900611.

Lee SH, Lee SL, Kim HY . Electro-optic characteristics and switching principle of a nematic liquid crystal cell controlled by fringe-field switching. Appl Phys Lett 1998; 73: 2881–2883.

Schadt M, Seiberle H, Schuster A . Optical patterning of multi-domain liquid-crystal displays with wide viewing angles. Nature 1996; 381: 212–215.

Mori H, Itoh Y, Nishiura Y, Nakamura T, Shinagawa Y . Performance of a novel optical compensation film based on negative birefringence of discotic compound for wide-viewing-angle twisted-nematic liquid-crystal displays. Jpn J Appl Phys 1997; 36: 143–147.

Ito Y, Watanabe J, Saitoh Y, Takada K, Morishima SI et al. Innovation of optical films using polymerized discotic materials: past, present and future. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2013; 44: 526–529.

Yamamoto E, Yui H, Katsuta S, Asaoka Y, Maeda T et al. Wide viewing LCDs using novel microstructure film. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2014; 45: 385–388.

Ohmuro K, Kataoka S, Sasaki T, Koike Y . Development of super-high-image-quality vertical-alignment-mode LCDs. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 1997; 28: 845–850.

Takeda A, Kataoka S, Sasaki T, Chida H, Tsuda H et al. A super-high image quality multi-domain vertical alignment LCD by new rubbing-less technology. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 1998; 29: 1077–1080.

Kim KH, Lee K, Park SB, Song JK, Kim SN et al. Domain Divided Vertical Alignment Mode with Optimized Fringe Field Effect. Proceedings of the 18th IDRC, Asia Display 1998; 98: 383–386.

Lee SH, Kim SM, Wu ST . Emerging vertical-alignment liquid-crystal technology associated with surface modification using UV-curable monomer. J Soc Inf Display 2009; 17: 551–559.

Kim SS, You BH, Cho JH, Kim DG, Berkeley BH et al. An 82-in. ultra-definition 120-Hz LCD TV using new driving scheme and advanced Super PVA technology. J Soc Inf Display 2009; 17: 71–78.

Vepakomma KH, Ishikawa T, Greene RG . Stress induced substrate Mura in curved LCD. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2015; 46: 634–636.

Hsiao K, Tang GF, Yu G, Zhang ZW, Xu XJ et al. Development and analysis of technical challenges in the world's largest (110-in.) curved LCD. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2015; 46: 1059–1062.

Oh-e M, Kondo K . Electro-optical characteristics and switching behavior of the in-plane switching mode. Appl Phys Lett 1995; 67: 3895–3897.

Oh-e M, Kondo K . Response mechanism of nematic liquid crystals using the in-plane switching mode. Appl Phys Lett 1996; 69: 623–625.

Hong SH, Park IC, Kim HY, Lee SH . Electro-optic characteristic of fringe-field switching mode depending on rubbing direction. Jpn J Appl Phys 2000; 39: L527–L530.

Yu IH, Song IS, Lee JY, Lee SH . Intensifying the density of a horizontal electric field to improve light efficiency in a fringe-field switching liquid crystal display. J Phys D Appl Phys 2006; 39: 2367–2372.

Chen HW, Peng FL, Luo ZY, Xu DM, Wu ST et al. High performance liquid crystal displays with a low dielectric constant material. Opt Mater Express 2014; 4: 2262–2273.

Yun HJ, Jo MH, Jang IW, Lee SH, Ahn SH et al. Achieving high light efficiency and fast response time in fringe field switching mode using a liquid crystal with negative dielectric anisotropy. Liq Cryst 2012; 39: 1141–1148.

Chen HW, Gao YT, Wu ST . n-FFS vs. p-FFS: who wins? SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2015; 46: 735–738.

Chen Y, Luo ZY, Peng FL, Wu ST . Fringe-field switching with a negative dielectric anisotropy liquid crystal. J Display Technol 2013; 9: 74–77.

Tang CW, VanSlyke SA . Organic electroluminescent diodes. Appl Phys Lett 1987; 51: 913–915.

Brütting W, Berleb S, Mückl AG . Device physics of organic light-emitting diodes based on molecular materials. Org Electron 2001; 2: 1–36.

Pfeiffer M, Leo K, Zhou X, Huang JS, Hofmann M et al. Doped organic semiconductors: physics and application in light emitting diodes. Org Electron 2003; 4: 89–103.

Kondakov DY . Characterization of triplet-triplet annihilation in organic light-emitting diodes based on anthracene derivatives. J Appl Phys 2007; 102: 114504.

Baldo MA, Lamansky S, Burrows PE, Thompson ME, Forrest SR . Very high-efficiency green organic light-emitting devices based on electrophosphorescence. Appl Phys Lett 1999; 75: 4–6.

Uoyama H, Goushi K, Shizu K, Nomura H, Adachi C . Highly efficient organic light-emitting diodes from delayed fluorescence. Nature 2012; 492: 234–238.

Park YS, Lee S, Kim KH, Kim SY, Lee JH et al. Exciplex-forming co-host for organic light-emitting diodes with ultimate efficiency. Adv Funct Mater 2013; 23: 4914–4920.

Song DD, Zhao SL, Luo YC, Aziz H . Causes of efficiency roll-off in phosphorescent organic light emitting devices: triplet-triplet annihilation versus triplet-polaron quenching. Appl Phys Lett 2010; 97: 243304.

Giebink N, D’Andrade BW, Weaver MS, Brown JJ, Forrest SR . Direct evidence for degradation of polaron excited states in organic light emitting diodes. J Appl Phys 2009; 105: 124514.

Seino Y, Sasabe H, Pu YJ, Kido J . High-performance blue phosphorescent OLEDs using energy transfer from exciplex. Adv Mater 2014; 26: 1612–1616.

Kuma H, Hosokawa C . Blue fluorescent OLED materials and their application for high-performance devices. Sci Technol Adv Mater 2014; 15: 034201.

Liang HW, Luo ZY, Zhu RD, Dong YJ, Lee JH et al. High efficiency quantum dot and organic LEDs with a back-cavity and a high index substrate. J Phys D Appl Phys 2016; 49: 145103.

Yamamoto T, Aono Y, Tsumura M . Guiding principles for high quality motion picture in AMLCDs applicable to TV monitors. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2000; 31: 456–459.

Kurita T . Moving picture quality improvement for hold-type AM-LCDs. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2001; 32: 986–989.

Igarashi Y, Yamamoto T, Tanaka Y, Someya J, Nakakura Y et al. Summary of moving picture response time (MPRT) and futures. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2004; 35: 1262–1265.

Someya J, Sugiura H . Evaluation of liquid-crystal-display motion blur with moving-picture response time and human perception. J Soc Inf Display 2007; 15: 79–86.

Peng FL, Chen HW, Gou FW, Lee YH, Wand M et al. Analytical equation for the motion picture response time of display devices. J Appl Phys 2017; 121: 023108.

Chen HW, Peng FL, Gou FW, Lee YH, Wand M et al. Nematic LCD with motion picture response time comparable to organic LEDs. Optica 2016; 3: 1033–1034.

Hirakata JI, Shingai A, Tanaka Y, Ono K, Furuhashi T . Super-TFT-LCD for moving picture images with the blink backlight system. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2001; 32: 990–993.

Furuhashi T, Kawabe K, Hirakata JI, Tanaka Y, Sato T . High quality TFT-LCD system for moving picture. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2002; 33: 1284–1287.

Yamamoto T, Sasaki S, Igarashi Y, Tanaka Y . Guiding principles for high-quality moving picture in LCD TVs. J Soc Inf Display 2006; 14: 933–940.

Ito H, Ogawa M, Sunaga S . Evaluation of an organic light-emitting diode display for precise visual stimulation. J Vis 2013; 13: 6.

Murawski C, Leo K, Gather MC . Efficiency roll-off in organic light-emitting diodes. Adv Mater 2013; 25: 6801–6827.

Féry C, Racine B, Vaufrey D, Doyeux H, Cinà S . Physical mechanism responsible for the stretched exponential decay behavior of aging organic light-emitting diodes. Appl Phys Lett 2005; 87: 213502.

Lee JH, Zhu XY, Lin YH, Choi WK, Lin TC et al. High ambient-contrast-ratio display using tandem reflective liquid crystal display and organic light-emitting device. Opt Express 2005; 13: 9431–9438.

Ge ZB, Wu ST . Transflective Liquid Crystal Displays. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2010.

Walker G . GD-Itronix Dynavue Technology. The ultimate outdoor-readable touch-screen display. Rugged PC Rev 2007. Available at: http://www.ruggedpcreview.com/3_technology_itronix_dynavue.html.

Zhu RD, Chen HW, Kosa T, Coutino P, Tan GJ et al. High-ambient-contrast augmented reality with a tunable transmittance liquid crystal film and a functional reflective polarizer. J Soc Inf Display 2016; 24: 229–233.

Chen HW, Tan GJ, Li MC, Lee SL, Wu ST . Depolarization effect in liquid crystal displays. Opt Express 2017; 25: 11315–11328.

Mills PR, Tomkins SC, Schlangen LJ . The effect of high correlated colour temperature office lighting on employee wellbeing and work performance. J Circadian Rhythms 2007; 5: 2.

Lee JH, Park KH, Kim SH, Choi HC, Kim BK et al. AH-IPS, superb display for mobile device. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2013; 44: 32–33.

Chen HW, Zhu RD, He J, Duan W, Hu W et al. Going beyond the limit of an LCD’s color gamut. Light Sci Appl 2017; 6: e17043.

ITU. Parameter Values for the HDTV Standards for Production and International Programme Exchange. Geneva, Switzerland: ITU; 2002 ITU-R Recommendation BT.709-5.

Adobe Systems Inc. Adobe RGB (1998) Color Image Encoding. San Jose, USA: Adobe Systems Inc.; 2005.

ITU. Parameter Values for Ultra-High Definition Television Systems for Production and International Programme Exchange. Geneva, Switzerland: ITU; 2015.

Masaoka K, Nishida Y, Sugawara M, Nakasu E . Design of primaries for a wide-gamut television colorimetry. IEEE Trans Broadcast 2010; 56: 452–457.

Kobayashi S, Mikoshiba S, Lim S . LCD Backlights. New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2009.

Xie RJ, Hirosaki N, Takeda T . Wide color gamut backlight for liquid crystal displays using three-band phosphor-converted white light-emitting diodes. Appl Phys Express 2009; 2: 022401.

Wang L, Wang XJ, Kohsei T, Yoshimura KI, Izumi M et al. Highly efficient narrow-band green and red phosphors enabling wider color-gamut LED backlight for more brilliant displays. Opt Express 2015; 23: 28707–28717.

Jang E, Jun S, Jang H, Lim J, Kim B et al. White-light-emitting diodes with quantum dot color converters for display backlights. Adv Mater 2010; 22: 3076–3080.

Steckel JS, Ho J, Hamilton C, Xi JQ, Breen C et al. Quantum dots: the ultimate down-conversion material for LCD displays. J Soc Inf Display 2015; 23: 294–305.

The European Parliament, The Council of the European Union Directive 2002/95/EC on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment. The European Parliament, The Council of the European Union, 2003; pp19–23.

Pickett NL, Harris JA, Gresty NC . Heavy metal-free quantum dots for display applications. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2015; 46: 168–169.

Pickett NL, Gresty NC, Hines MA . Heavy metal-free quantum dots making inroads for consumer applications. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2016; 47: 425–427.

Lee E, Wang CK, Hotz C, Hartlove J, Yurek J et al. ‘Greener’ quantum-dot enabled LCDs with BT.2020 color gamut. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2016; 47: 549–551.

Wyatt D, Chen HW, Wu ST . Wide-color-gamut LCDs with vivid color LED technology. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2017; 48: 992–995.

Li WJ, Yao L, Liu HC, Wang ZM, Zhang ST et al. Highly efficient deep-blue OLED with an extraordinarily narrow FHWM of 35 nm and a y coordinate<0.05 based on a fully twisting donor-acceptor molecule. J Mater Chem C 2014; 2: 4733–4736.

Hosoumi S, Yamaguchi T, Inoue H, Nomura S, Yamaoka R et al. Ultra-wide color gamut OLED display?using a deep-red phosphorescent device with high efficiency, long life, thermal stability, and absolute BT.2020 red chromaticity. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2017; 48: 13–16.

Li GJ, Fleetham T, Turner E, Hang XC, Li J . Highly efficient and stable narrow-band phosphorescent emitters for OLED applications. Adv Opt Mater 2015; 3: 390–397.

Riel H, Karg S, Beierlein T, Ruhstaller B, Rieß W . Phosphorescent top-emitting organic light-emitting devices with improved light outcoupling. Appl Phys Lett 2003; 82: 466–468.

Kim E, Chung J, Lee J, Cho H, Cho NS et al. A systematic approach to reducing angular color shift in cavity-based organic light-emitting diodes. Org Electron 2017; 48: 348–356.

Lee MT, Wang CL, Chan CS, Fu CC, Shih CY et al. Achieving a foldable and durable OLED display with BT.2020 color space using innovative color filter structure. J Soc Inf Display 2017; 25: 229–239.

Sasaki T, Yamaoka R, Nomura S, Yamamoto R, Takahashi K et al. A 13.3-inch 8K × 4K 664-ppi 120-Hz 12-bit display with super-wide color gamut for the BT.2020 standard. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2017; 48: 123–126.

Park JS, Chae H, Chung HK, Lee SI . Thin film encapsulation for flexible AM-OLED: a review. Semicond Sci Technol 2011; 26: 034001.

Lewis JS, Weaver MS . Thin-film permeation-barrier technology for flexible organic light-emitting devices. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron 2004; 10: 45–57.

Chou CT, Yu PW, Tseng MH, Hsu CC, Shyue JJ et al. Transparent conductive gas-permeation barriers on plastics by atomic layer deposition. Adv Mater 2013; 25: 1750–1754.

Chwang AB, Rothman MA, Mao SY, Hewitt RH, Weaver MS et al. Thin film encapsulated flexible organic electroluminescent displays. Appl Phys Lett 2003; 83: 413–415.

Kondakov DY, Sandifer JR, Tang CW, Young RH . Nonradiative recombination centers and electrical aging of organic light-emitting diodes: direct connection between accumulation of trapped charge and luminance loss. J Appl Phys 2003; 93: 1108–1109.

Hack M, Weaver MS, Brown JJ . Status and opportunities for phosphorescent OLED lighting. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2017; 48: 187–190.

Scholz S, Kondakov D, Lüssem B, Leo K . Degradation mechanisms and reactions in organic light-emitting devices. Chem Rev 2015; 115: 8449–8503.

Zhang Y, Lee J, Forrest SR . Tenfold increase in the lifetime of blue phosphorescent organic light-emitting diodes. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 5008.

Lee J, Jeong C, Batagoda T, Coburn C, Thompson ME et al. Hot excited state management for long-lived blue phosphorescent organic light-emitting diodes. Nat Commun 2017; 8: 15566.

Hashimoto N, Ogita K, Nowatari H, Takita Y, Kido H et al. Investigation of effect of triplet-triplet annihilation and molecular orientation on external quantum efficiency of ultrahigh-efficiency blue fluorescent device. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2016; 47: 301–304.

Lin BY, Lee MZ, Tseng PC, Lee JH, Chiu TL et al. 16.1-times elongation of operation lifetime in a blue TTA-OLED by using new ETL and EML materials. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2017; 48: 1928–1931.

Lin BY, Easley CJ, Chen CH, Tseng PC, Lee MZ et al. Exciplex-sensitized triplet−triplet annihilation in heterojunction organic thin-film. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2017; 9: 10963–10970.

3M Optical Systems Division. Vikuiti™ Dual Brightness Enhancement Film (DBEF). St. Paul, USA: 3M; 2008.

Youn W, Lee J, Xu MF, Singh R, So F . Corrugated sapphire substrates for organic light-emitting diode light extraction. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2015; 7: 8974–8978.

Kim JB, Lee JH, Moon CK, Kim SY, Kim JJ . Highly enhanced light extraction from surface plasmonic loss minimized organic light-emitting diodes. Adv Mater 2013; 25: 3571–3577.

Furno M, Meerheim R, Hofmann S, Lüssem B, Leo K . Efficiency and rate of spontaneous emission in organic electroluminescent devices. Phys Rev B 2012; 85: 115205.

Lüssem B, Riede M, Leo K . Doping of organic semiconductors. Phys Status Solidi (A) 2013; 210: 9–43.

Lee C, Kim JJ . Enhanced light out-coupling of OLEDs with low haze by inserting randomly dispersed nanopillar arrays formed by lateral phase separation of polymer blends. Small 2013; 9: 3858–3863.

Lin HY, Chen KY, Ho YH, Fang JH, Hsu SC et al. Luminance and image quality analysis of an organic electroluminescent panel with a patterned microlens array attachment. J Optics 2010; 12: 085502.

Tan GJ, Zhu RD, Tsai YS, Lee KC, Luo ZY et al. High ambient contrast ratio OLED and QLED without a circular polarizer. J Phys D Appl Phys 2016; 49: 315101.

Tang CW, VanSlyke SA, Chen CH . Electroluminescence of doped organic thin films. J Appl Phys 1989; 65: 3610–3616.

Shi JM, Tang CW . Doped organic electroluminescent devices with improved stability. Appl Phys Lett 1997; 70: 1665–1667.

Hosokawa C, Higashi H, Nakamura H, Kusumoto T . Highly efficient blue electroluminescence from a distyrylarylene emitting layer with a new dopant. Appl Phys Lett 1995; 67: 3853–3855.

Kido J, Kimura M, Nagai K . Multilayer white light-emitting organic electroluminescent device. Science 1995; 267: 1332–1334.

Huang YS, Jou JH, Weng WK, Liu JM . High-efficiency white organic light-emitting devices with dual doped structure. Appl Phys Lett 2002; 80: 2782–2784.

Adachi C, Baldo M, Forrest SR, Lamansky S, Thompson ME et al. High-efficiency red electrophosphorescence devices. Appl Phys Lett 2001; 78: 1622–1624.

Meerheim R, Scholz S, Olthof S, Schwartz G, Reineke S et al. Influence of charge balance and exciton distribution on efficiency and lifetime of phosphorescent organic light-emitting devices. J Appl Phys 2008; 104: 014510.

Tanaka D, Sasabe H, Li YJ, Su SJ, Takeda T et al. Ultra high efficiency green organic light-emitting devices. Jpn J Appl Phys 2007; 46: L10–L12.

Holmes RJ, Forrest SR, Tung YJ, Kwong RC, Brown JJ et al. Blue organic electrophosphorescence using exothermic host-guest energy transfer. Appl Phys Lett 2003; 82: 2422–2424.

Chopra N, Lee J, Xue JG, So F . High-efficiency blue emitting phosphorescent OLEDs. IEEE Trans Electron Devices 2010; 57: 101–107.

D'Andrade BW, Holmes RJ, Forrest SR . Efficient organic electrophosphorescent white-light-emitting device with a triple doped emissive layer. Adv Mater 2004; 16: 624–628.

Sun YR, Forrest SR . High-efficiency white organic light emitting devices with three separate phosphorescent emission layers. Appl Phys Lett 2007; 91: 263503.

Kim KH, Liao JL, Lee SW, Sim B, Moon CK et al. Crystal organic light-emitting diodes with perfectly oriented non-doped Pt-based emitting layer. Adv Mater 2016; 28: 2526–2532.

Wang ZB, Helander MG, Qiu J, Puzzo DP, Greiner MT et al. Unlocking the full potential of organic light-emitting diodes on flexible plastic. Nat Photonics 2011; 5: 753–757.

Shin H, Lee JH, Moon CK, Huh JS, Sim B et al. Sky-blue phosphorescent OLEDs with 34.1% external quantum efficiency using a low refractive index electron transporting layer. Adv Mater 2016; 28: 4920–4925.

Reineke S, Lindner F, Schwartz G, Seidler N, Walzer K et al. White organic light-emitting diodes with fluorescent tube efficiency. Nature 2009; 459: 234–238.

Yamada Y, Inoue H, Mitsumori S, Watabe T, Ishisone T et al. Achievement of blue phosphorescent organic light-emitting diode with high efficiency, low driving voltage, and long lifetime by exciplex-triplet energy transfer technology. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2016; 47: 711–714.

Wen SW, Lee MT, Chen CH . Recent development of blue fluorescent OLED materials and devices. J Display Technol 2005; 1: 90–99.

Suzuki T, Nonaka Y, Watabe T, Nakashima H, Seo S et al. Highly efficient long-life blue fluorescent organic light-emitting diode exhibiting triplet-triplet annihilation effects enhanced by a novel hole-transporting material. Jpn J Appl Phys 2014; 53: 052102.

Jou JH, Kumar S, Agrawal A, Li TH, Sahoo S . Approaches for fabricating high efficiency organic light emitting diodes. J Mater Chem C 2015; 3: 2974–3002.

Soneira RM . Galaxy Note8 OLED Display Technology Shoot-Out. Amherst, USA: DisplayMate; 2017.

Jang J . Displays develop a new flexibility. Mater Today 2006; 9: 46–52.

Komatsu R, Nakazato R, Sasaki T, Suzuki A, Senda N et al. Repeatedly foldable book-type AMOLED display. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2014; 45: 326–329.

Noda M, Kobayashi N, Katsuhara M, Yumoto A, Ushikura S et al. An OTFT-driven rollable OLED display. J Soc Inf Display 2011; 19: 316–322.

Liang JJ, Li L, Niu XF, Yu ZB, Pei QB . Elastomeric polymer light-emitting devices and displays. Nat Photonics 2013; 7: 817–824.

Jo JH, Jhe JH, Ryu SC, Lee KH, Shin JK . A novel curved LCD with highly durable and slim profile. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2010; 41: 1671–1674.

Vogels JPA, Klink SI, Penterman R, de Koning H, Huitema EEA et al. Robust flexible LCDs with paintable technology. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2004; 35: 767–769.

Fujisaki Y, Sato H, Yamamoto T, Fujikake H, Tokito S et al. Flexible color LCD panel driven by low-voltage-operation organic TFT. J Soc Inf Display 2007; 15: 501–506.

Ishinabe T, Obonai Y, Fujikake H . A foldable ultra-thin LCD using a coat-debond polyimide substrate and polymer walls. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2016; 47: 83–86.

Harding MJ, Horne IP, Yaglioglu B . Flexible LCDs enabled by OTFT. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2017; 48: 793–796.

Greinert N, Schoenefeld C, Suess P, Klasen-Memmer M, Bremer M et al. Opening the door to new LCD applications via polymer walls. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2015; 46: 382–385.

Lee S, Moon J, Yang S, Rhim J, Kim B et al. Development of zero-bezel display utilizing a waveguide image transformation element. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2017; 48: 612–614.

Yamazaki A, Wu CL, Cheng WC, Badano A . Spatial resolution characteristics of organic light-emitting diode displays: a comparative analysis of MTF for handheld and workstation formats. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2013; 44: 419–422.

Chen HW, Zhu RD, Käläntär K, Wu ST . Quantum dot-enhanced LCDs with wide color gamut and broad angular luminance distribution. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2016; 47: 1413–1416.

Käläntär K . A directional backlight with narrow angular luminance distribution for widening the viewing angle for an LCD with a front-surface light-scattering film. J Soc Inf Display 2012; 20: 133–142.

Gao YT, Luo ZY, Zhu RD, Hong Q, Wu ST et al. A high performance single-domain LCD with wide luminance distribution. J Display Technol 2015; 11: 315–324.

Yang JP, Hsiang EL, Chen HMP . Wide viewing angle TN LCD enhanced by printed quantum-dots film. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2016; 47: 21–24.

Kim HJ, Shin MH, Lee JY, Kim JH, Kim YJ . Realization of 95% of the Rec. 2020 color gamut in a highly efficient LCD using a patterned quantum dot film. Opt Express 2017; 25: 10724–10734.

Liu YK, Lai J, Li XN, Xiang Y, Li JT et al. A quantum dot array for enhanced tricolor liquid-crystal display. IEEE Photonics Technol 2017; 9: 6900207.

Han CW, Kim KM, Bae SJ, Choi HS, Lee JM et al. 55-inch FHD OLED TV employing new tandem WOLEDs. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2012; 43: 279–281.

Shin HJ, Park KM, Takasugi S, Jeong YS, Kim JM et al. A high-image-quality OLED display for large-size and premium TVs. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2017; 48: 1134–1137.

Singh M, Haverinen HM, Dhagat P, Jabbour GE . Inkjet printing—process and its applications. Adv Mater 2010; 22: 673–685.

Chen PY, Chen CL, Chen CC, Tsai L, Ting HC et al. 65-inch inkjet printed organic light-emitting display panel with high degree of pixel uniformity. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2014; 45: 396–398.

Levermore P, Schenk T, Tseng HR, Wang HJ, Heil H et al. Ink-jet-printed OLEDs for display applications. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2016; 47: 484–486.

Reinhard E, Heidrich W, Debevec P, Pattanaik S, Ward G et al. High Dynamic Range Imaging: Acquisition, Display, and Image-Based Lighting2nd edn.San Francisco, CA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann; 2010.

Kwon JU, Bang S, Kang D, Yoo JJ . The required attribute of displays for high dynamic range. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2016; 47: 884–887.

Zhu RD, Chen HW, Wu ST . Achieving 12-bit perceptual quantizer curve with liquid crystal display. Opt Express 2017; 25: 10939–10946.

Chen HF, Sung J, Ha T, Park Y, Hong CW . Backlight Local Dimming Algorithm for High Contrast LCD-TV. New Delhi, India: Proceedings of ASID; 2006, pp168–pp171.

Lin FC, Huang YP, Liao LY, Liao CY, Shieh HPD et al. Dynamic backlight gamma on high dynamic range LCD TVs. J Display Technol 2008; 4: 139–146.

Chen HF, Ha TH, Sung JH, Kim HR, Han BH . Evaluation of LCD local-dimming-backlight system. J Soc Inf Display 2010; 18: 57–65.

Yoo O, Nam S, Choi J, Yoo S, Kim KJ et al. Contrast enhancement based on advanced local dimming system for high dynamic range LCDs. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2017; 48: 1667–1669.

Chen HW, Zhu RD, Li MC, Lee SL, Wu ST . Pixel-by-pixel local dimming for high-dynamic-range liquid crystal displays. Opt Express 2017; 25: 1973–1984.

Daly S, Kunkel T, Sun X, Farrell S, Crum P . Viewer preferences for shadow, diffuse, specular, and emissive luminance limits of high dynamic range displays. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2013; 44: 563–566.

SMPTE. SMPTE ST 2084-2014 High dynamic range electro-optical transfer function of mastering reference displays. SMPTE 2014.

Chen CH, Lin FC, Hsu YT, Huang YP, Shieh HP . A field sequential color LCD based on color fields arrangement for color breakup and flicker reduction. J Display Technol 2009; 5: 34–39.

Lin FC, Huang YP, Wei CM, Shieh HPD . Color-breakup suppression and low-power consumption by using the Stencil-FSC method in field-sequential LCDs. J Soc Inf Display 2009; 17: 221–228.

Chen HW, Hu MG, Peng FL, Li J, An ZW et al. Ultra-low viscosity liquid crystal materials. Opt Mater Express 2015; 5: 655–660.

Channin DJ . Triode optical gate: a new liquid crystal electro-optic device. Appl Phys Lett 1975; 26: 603–605.

Xiang CY, Guo JX, Sun XW, Yin XJ, Qi GJ . A fast response, three-electrode liquid crystal device. Jpn J Appl Phys 2003; 42: 763.

Jiao MZ, Ge ZB, Wu ST, Choi WK . Submillisecond response nematic liquid crystal modulators using dual fringe field switching in a vertically aligned cell. Appl Phys Lett 2008; 92: 111101.

Chen HW, Luo ZY, Xu DM, Peng FL, Wu ST et al. A fast-response A-film-enhanced fringe field switching liquid crystal display. Liq Cryst 2015; 42: 537–542.

Chen HW, Gou FW, Wu ST . Submillisecond-response nematic liquid crystals for augmented reality displays. Opt Mater Express 2017; 7: 195–201.

Huang YG, Chen HW, Tan GJ, Tobata H, Yamamoto SI et al. Optimized blue-phase liquid crystal for field-sequential-color displays. Opt Mater Express 2017; 7: 641–650.

Chen HW, Lan YF, Tsai CY, Wu ST . Low-voltage blue-phase liquid crystal display with diamond-shape electrodes. Liq Cryst 2017; 44: 1124–1130.

Tan GJ, Lee YH, Gou FW, Hu MG, Lan YF et al. Macroscopic model for analyzing the electro-optics of uniform lying helix cholesteric liquid crystals. J Appl Phys 2017; 121: 173102.

Castles F, Morris SM, Gardiner DJ, Malik QM, Coles HJ . Ultra-fast-switching flexoelectric liquid-crystal display with high contrast. J Soc Inf Display 2010; 18: 128–133.

Ghosh A, Donoghue EP, Khayrullin I, Ali T, Wacyk I et al. Directly patterened 2645 Ppi full color OLED microdisplay for head mounted wearables. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2016; 47: 837–840.

Kimura K, Onoyama Y, Tanaka T, Toyomura N, Kitagawa H . New pixel driving circuit using self-discharging compensation method for high- resolution OLED micro displays on a silicon backplane. J Soc Inf Display 2017; 25: 167–176.

Armitage D, Underwood I, Wu ST . Introduction to Microdisplays. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2006.

Li YW, Lin CW, Chen KY, Fan-Chiang KH, Kuo HC et al. Front-lit LCOS for wearable applications. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2014; 45: 234–236.

Reinert-Weiss CJ, Baur H, Al Nusayer SA, Duhme D, Frühauf N . Development of active matrix LCD for use in high-resolution adaptive headlights. J Soc Inf Display 2017; 25: 90–97.

Yao L, Langguth N, Schroth D, Maisch R . Driving forces-how mobility of tomorrow influences technologies of today. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2017; 48: 775–778.

Lin CH, Lo WB, Liu KH, Liu CY, Lu JK et al. Novel transparent LCD with tunable transparency. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2012; 43: 1159–1162.

Okuyama K, Nakahara T, Numata Y, Nakamura T, Mizuno M et al. Highly transparent LCD using new scattering-type liquid crystal with field sequential color edge light. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2017; 48: 1166–1169.

Görrn P, Sander M, Meyer J, Kröger M, Becker E et al. Towards see-through displays: fully transparent thin-film transistors driving transparent organic light-emitting diodes. Adv Mater 2006; 18: 738–741.

Wang MJ, Chen YQ, Liu XN, Yuan S, Li N et al. A new technology of mirror LCD. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 2017; 48: 1160–1162.

Acknowledgements

We thank Guanjun Tan and Ruidong Zhu for helpful discussions and AFOSR for partial financial support under contract No. FA9550-14-1-0279.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, HW., Lee, JH., Lin, BY. et al. Liquid crystal display and organic light-emitting diode display: present status and future perspectives. Light Sci Appl 7, 17168 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2017.168

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2017.168

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hydrogels for active photonics

Microsystems & Nanoengineering (2024)

-

Intelligent block copolymer self-assembly towards IoT hardware components

Nature Reviews Electrical Engineering (2024)

-

Planning method of droplet fusion scheduling based on mixed-integer programming

Science China Technological Sciences (2024)

-

A New Method for Evaluating the Influence of Coatings on the Strength and Fatigue Behavior of Flexible Glass

Journal of Electronic Materials (2024)

-

Ultrafine and crosstalk-free 2D tactile sensor by using active-matrix thin-film transistor array

ROBOMECH Journal (2023)