Abstract

Imaging cells and microvasculature in the living brain is crucial to understanding an array of neurobiological phenomena. Here, we introduce a skull optical clearing window for imaging cortical structures at synaptic resolution. Combined with two-photon microscopy, this technique allowed us to repeatedly image neurons, microglia and microvasculature of mice. We applied it to study the plasticity of dendritic spines in critical periods and to visualize dendrites and microglia after laser ablation. Given its easy handling and safety, this method holds great promise for application in neuroscience research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the development of transgenic technology1, two-photon microscopy has made it possible to image neurons, glia and microvasculature in live mice over time intervals from seconds to years2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8. This technique has become a powerful tool to understand an array of neurobiological phenomena, including the plasticity of individual synapses and neuronal network activity4, 9.

However, the strong scattering caused by the skull over the cortex hinders the observation of fluorescently labeled neuronal structures and microvasculature10, 11. To overcome this obstacle, various cranial window methods were developed, including the open-skull glass window12, 13, the thinned-skull cranial window14, 15 and their variants16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28. The open-skull glass window is formed by removing a section of the skull and replacing it with a glass coverslip and may induce an inflammatory response within 3 weeks after surgery12, 29. The thinned-skull cranial window is realized by thinning the skull down (to <25 μm). This is a minimally invasive method, but it requires repeatedly thinning the skull due to bone regrowth, which makes it relatively difficult to use14. To meet different needs, variants based on craniotomy or skull-thinning surgery have been developed. However, they cannot circumvent the problems inherent to current cranial windows: the associated inflammatory response, the complexities in surgical procedures and high skill requirements for laboratory personnel. Thus, it is urgent to develop a safe and easy-handling cranial window technique for cortical neuroimaging.

The tissue optical clearing technique can reduce the scattering of tissue30, 31 and has great potential for solving this problem. By combining it with various optical microscopy techniques, three-dimensional visualization of ex vivo brain, spinal cord, etc. with high resolution has been possible, which has helped to achieve major breakthroughs in neuroscience research32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38. In addition, some attempts were made to reduce the scattering of the skull ex vivo36, 37, 39, 40, 41. However, the optical clearing of the skull in vivo has not been sufficiently studied. In recent years, researchers have also performed some in vivo experiments to reduce the scattering of the skull, such as applying reagents on the skull to achieve in vivo imaging of the cortex42, 43, 44. However, it remains impossible to image the cortical structures at synaptic resolution due to the limited optical clearing efficacy of these methods.

Thus, our basic idea is to develop an easy-handling and safe skull optical clearing window (SOCW) for in vivo imaging of the cortical structures at synaptic resolution. Combined with two-photon microscopy, this SOCW technique enables us to repeatedly image the dendritic protrusions, microglia processes and blood capillaries in the superficial layers of the cortex. In addition, we investigated the safety of the SOCW technique, concluding that the method is safe. Then, we applied this approach to monitor the plasticity of dendritic protrusions in critical periods and to visualize the changes in dendrites and microglia upon laser injury.

Materials and methods

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Experimental Animal Management Ordinance of Hubei Province, China and carried out in accordance with the guidelines for humane care of animals. The following mouse strains were used: Thy1-YFP-H; Cx3cr1EGFP/+; Sst-IRES-Cre::Ai14; and wild-type C57BL/6. Transgenic mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and housed and bred in Wuhan National Laboratory for Optoelectronics with a normal cycle (12 h light/dark). Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were supplied by the Wuhan University Center for Animal Experiment (Wuhan, China). Transgenic mice expressing yellow fluorescent protein under the control of the Thy1 promoter (Thy1-YFP-H) were used for imaging dendritic spines, whereas those expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein in microglia (Cx3cr1EGFP/+) were used for imaging microglia. Transgenic mice expressing red fluorescent protein (Sst-IRES-Cre::Ai14) were used for imaging cortical interneurons. Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were used for imaging the cerebral vasculature labeled with FITC-dextran (50 mg ml−1; 2 × 106 molecular weight; Sigma-Aldrich). The Thy1-YFP-H mice younger than postnatal day 14 (<P14) have inadequate numbers of brightly labeled cells for in vivo imaging. Thus, we selected the mice aged older than P14.

Reagents

The optical clearing agents (OCAs) used in this study include collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich; T8003), EDTA disodium (Sigma-Aldrich; D2900000) and glycerol (Sigma-Aldrich; 101640026). The OCAs were developed according to the composition of the skull. As we know, the skull consists of an inorganic matrix and an organic matrix. In addition, the main components of the inorganic matrix and organic matrix are calcium hydroxyapatite and collagen, respectively. As the mice grow older, the ratio of inorganic matrix to organic matrix increases. Therefore, for the infantile mice (<P20), collagenase was used to dissolve collagenous fiber; for the elder mice (>P20), EDTA disodium was used to chelate calcium ions (decalcification). In addition, glycerol was used to match the refractive index.

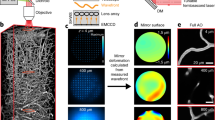

Schematic diagram of the SOCW technique

Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of the SOCW technique for cortical imaging. The main experimental procedures include head immobilization, skull optical clearing, cortical imaging and recovery (Figure 1a). After anesthesia, hair removal and scalp incision, mice were fixed with a custom-built immobilization device (Figure 1b) that consisted of a custom-built plate and a skull holder. Further, the skull holder was formed by two conventional double-edged razor blades sandwiching a layer of waterproof paper. On the surface of the skull-holder, dental cement was used to form a reservoir that prevented the OCA from leaking.

Schematic diagram of SOCW technique for cortical imaging. (a) Four steps: immobilization, skull optical clearing, cortical imaging and recovery. (b) A custom-built head immobilization device consisting of a skull-holder and a custom-built plate is used to reduce motion artifact during imaging. (c) Anatomical structure of mouse skull. (d) Schematic of the SOCW. A layer of plastic wrap is placed over the cleared skull to separate the water-immersion objective from the optical clearing agent (OCA). (e–g) The skull optical clearing methods for mice aged e P15–P20, f P21–P30, g older than P30, which include two steps, the first step is different for mice of different ages. Step 1: for mice aged P15–P20, the intact skull was topically treated with 10% collagenase (w v−1) for 5–10 min; for mice aged P21–P30, the intact skull was topically treated with 10% EDTA disodium (w v−1) for 5–10 min; for mice older than P30, the thinned skull (100 μm) was treated with 10% EDTA disodium (w v−1) for 5–10 min. Step 2: 80% glycerol (v v−1) was dropped onto the cleared skull.

The mouse skull is made up of two layers of compact bone sandwiching a layer of spongy bone (Figure 1c), and this structural heterogeneity produces a strong scattering effect. The clearing process takes approximately 15 min and comprises two steps: first, softening the outermost layer of the skull, and then, matching the refractive index. Before imaging, a layer of plastic wrap was placed over the cleared skull to separate the water-immersion objective from the OCA (Figure 1d). After imaging, we gently detached the holder from the skull, thoroughly cleaned the skull and the skin to remove the remaining glue, and sutured the scalp with sterile surgical sutures.

Skull optical clearing methods

Since components of the skull change with age, various clearing methods were developed for mice of different ages (Figure 1e–1g).

Step 1: For mice aged P15–P20, the intact skull was topically treated with 10% collagenase for 5–10 min (Figure 1e); for mice aged P21–P30, the reagent was replaced by 10% EDTA disodium (Figure 1f). The thickness of the skull increases as mice age; thus, for mice older than P30, we had to thin the skull to approximately 100 μm before clearing and then treat it with 10% EDTA disodium for 5–10 min (Figure 1g).

Step 2: We removed the first reagent above the skull by using a clean cotton ball, and then, 80% glycerol was dropped onto the skull.

In vivo two-photon imaging

In vivo images of YFP-expressing dendritic spines/EGFP-expressing microglia/FITC-dextran-labeled cerebral vasculature were acquired by a two-photon microscope (FV1200; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a Mai Tai Ti:sapphire laser (Spectra Physics, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at 925 nm. The output optical power was <40 mW to avoid phototoxicity. Image stacks were obtained with a step size of 1 μm using a water-immersion objective (25 ×, numerical aperture=1.05, working distance=2 mm; Olympus). To relocate the same location, low-resolution images of interest were obtained with a step size of 2 μm. After the initial fluorescence image was acquired, the OCAs were topically applied to the skull, and then, the same area was relocated and reimaged based on the brain vasculature map to assess the optical clearing efficacy.

Labeling of microglia and astrocytes in mouse cortex

Mice were perfused intracardially with 4% paraformaldehyde. The mouse brains were removed, postfixed and sectioned into 50 μm slices. To examine microglia in the mouse cortex, we used Cx3cr1EGFP/+ transgenic mice, and labeling of astrocytes was performed with antibodies against Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). Brain sections were stained for GFAP (Proteintech Group, Rosemont, IL, USA; 16825-1-AP; 1:100) using a normal immunostaining protocol. The images were acquired by a Zeiss 710 LSM confocal microscope (Oberkochen, Germany) and a Nikon Eclipse Ni-E wide-field microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

Laser ablation inside the cortex

The laser ablation inside the cortex was performed by focusing a laser beam on the cortex through the skull. The laser wavelength was 780 nm, and its power was approximately 60–80 mW at the sample. The beam remained at the position of interest for approximately 60 s to create a tiny injury site.

Data quantification

All data were analyzed by using Image J software that was developed by National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA). For spine dynamics in Figure 6, all analyses were performed manually on the raw image stacks. The newly formed spine was the one that was not in the first image but appeared in the second image. The eliminated spine was the one that appeared in the initial image but not in the second image. The elimination and formation rates of spine were, respectively, the number of spines that disappeared or appeared between two imaging time points, relative to the total number of spines in the initial image. In addition, we selected the two-dimensional projections that contained in-focus dendritic segments (with high image quality) to make figures. The quantified data were presented as the mean±s.e.m.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Results and discussion

Imaging the dendritic spines at synaptic resolution through the SOCW

First, we performed in vivo experiments to assess the optical clearing efficacy achieved by the SOCW method. We found that the image quality was considerably improved and that it was sufficient for imaging the dendritic spines through the cleared skull (Figure 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Figure 2a and 2b demonstrate the typical dendritic spines of Thy1-YFP neurons at the depths of 10–15 and 60–65 μm below the pial surface. Figure 2c and 2d show the fluorescence intensity for the same locations indicated by dashed lines in Figure 2a and 2b; we can observe that the image contrast is significantly improved through the cleared skull. Thus, we can achieve imaging of the structures at synaptic resolution through the SOCW.

Representative fluorescence images of the dendrites to assess the optical clearing efficacy achieved by the SOCW method. (a and b) Maximum projections across images a 10–15 μm and b 60–65 μm below the surface through the intact skull, before and after skull optical clearing (P30, n=10 mice). (c and d) Transverse plots corresponding to the same dendrites and spines indicated by the dashed line in a and b, showing that the fluorescence intensity is significantly improved. Scale bar=10 μm.

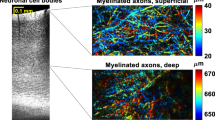

The imaging depth through the SOCW

Then, we evaluated the imaging depth through the SOCW. Figure 3a demonstrates the image along the depth direction (x–z). In addition to significant increases in fluorescence intensity, the imaging depth also obviously enhanced after clearing. For further quantitative comparison, 10 groups were selected to conduct a statistical analysis, and the mean depth increased approximately twofold (Figure 3b). Considering that confocal microscopy is more common than two-photon microscopy, we also used confocal microscopy to perform the same experiment. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows that the SOCW is also compatible with confocal imaging and that the imaging depth increases from 20 to 60 μm. These images were obtained with consistent parameters to ensure the fair comparison of the results before and after clearing. Furthermore, we could obtain good visibility of dendrites (Figure 3c), microglia (Figure 3d) and blood vessels (Figure 3e) up to 250 μm below the pial surface by optimizing the imaging parameters, which demonstrates that the imaging depth certainly reaches up to 250 μm.

Imaging depth through the SOCW. (a) Orthogonal (x–z) projections of dendrites through the intact skull, before and after skull optical clearing, demonstrating that the depth is obviously enhanced after clearing (the imaging parameter and data processing were the same). Scale bar=10 μm. (b) The depth when imaging the dendrites of Thy1-YFP neurons, before and after skull optical clearing (P30, n=10 mice; statistical method: one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); P<0.001). (c–e) Imaging depth through the SOCW after optimizing the imaging parameters (P30, n=6 mice). (c) Dendrites and spines of Thy1-YFP neurons at different depths through the SOCW. Scale bar=10 μm. (d) Maximum z-axis projections across 50 μm of microglia through the SOCW. Scale bar=25 μm. (e) Maximum z-axis projections across 50 μm of FITC-dextran-filled cerebral vasculature through the SOCW. Scale bar=50 μm.

The above results also show that the SOCW technique is compatible with various fluorescent proteins and dyes, including GFP (Figure 3d), YFP (Figure 3c), RFP (Supplementary Fig. 3), FITC (Figure 3e) and tetramethylrhodamine (Supplementary Fig. 4). Therefore, the SOCW technique demonstrates flexibility and widespread applicability.

The repeatability of the SOCW technique

We also assessed the repeatability of the SOCW technique. The skull could return to the opaque state very quickly after treatment with PBS (phosphate-buffered saline), and retreatment with OCAs made the skull re-clear very quickly (Figure 4a), which shows that the SOCW is switchable. Obviously, bone re-grows with time; if the imaging interval was beyond one day, the time for clearing was slightly longer than the first time. Despite this caveat, we could repeatedly observe the dendrites (Figure 4b), spines (Figure 4c), microglia (Supplementary Fig. 5a) and microvasculature (Supplementary Fig. 5b) through the SOCW. Thus, we could achieve short- and long-term repetitive imaging of the cortex through the SOCW.

The repeatability of the SOCW. (a) Repeated imaging of the dendrites and spines of Thy1-YFP neurons within a few hours, which shows that the SOCW is switchable (P30, n=10 mice). (b and c) Repeated imaging of the dendrites b and spines c of Thy1-YFP neurons obtained over a 1-day interval (P28–P30, n=10 mice). Scale bar=10 μm.

Safety assessment of the SOCW technique

The above repeated imaging of the same position shows an absence of inflammation. In addition, we performed both in vivo (Figure 5a and 5b) and ex vivo (Figure 5c, 5d and Supplementary Fig. 6) experiments to assess the safety of this method. First, we observed microglia in vivo 0 and 2 days after craniotomy and after clearing, respectively. We found that microglia remained at the same position (Figure 5a) when viewed through the SOCW, which indicates that the SOCW technique does not affect the microenvironment. In contrast, the distribution of microglia seen through the open-skull glass window was completely different (Supplementary Fig. 7a). The craniotomy evidently induced the movement of microglia.

Safety assessment of the SOCW technique. (a) Distribution of microglia through the SOCW. After the SOCW technique, microglia remain at the same position (P28, n=4 mice). Scale bar=25 μm. (b) Maximum projections (z-axis) across 10–40 μm of FITC-dextran-filled cerebral vasculature under the SOCW obtained 0 (P28, n=4 mice) and 21 days after the treatment. We observe that the cerebrovascular morphology remains nearly unchanged 21 days after forming the SOCW. Scale bar=25 μm. (c) Histological images of microglia in the case of the SOCW technique; microglia in both the treated and control sides appear normal (P30, n=3 mice). Scale bar=1 mm (above) and 25 μm (below). (d) GFAP expression under the SOCW technique. The treated and control hemispheres show similar levels of GFAP expression (P38, n=3 mice). Scale bar=1 mm (above) and 50 μm (below).

Previous studies showed that the injury of the cortex could trigger outgrowth and remodeling of the surface pial vasculature19, 45, so the structures of superficial cerebral vessels under craniotomy showed alterations in topology that may be due to angiogenesis in the meninges caused by inevitable damage. In this work, we also imaged the FITC-dextran-filled cerebral vasculature of C57BL/6 mice 0 and 21 days after clearing and found that the distribution of cerebral vasculature was nearly the same (Figure 5b). This result indicates that the optical clearing treatment produces no cortical injury.

In general, the microglia are active maximally 2 days after craniotomy12, 19, 29, and the expression of GFAP may be upregulated in activated astrocytes 7–14 days after injury19, 29, 45. Thus, we carried out ex vivo experiments to observe microglia 2 days after surgery and visualize the expression of the GFAP in astrocytes 10 days after surgery. We found that the microglia in both the SOCW and the control hemisphere remained in a non-active state with a highly branched morphology (Figure 5c). Moreover, the density of microglia in cortical layer I/II under the SOCW is consistent with that under the contralateral side (0.99±0.04), which is similar with that through the thinned-skull cranial window24, 29. In addition, the GFAP immunostaining patterns exhibit similar levels of GFAP expression for both sides (Figure 5d), which means that the astrocytes were not activated.

In contrast, through the open-skull glass window, the microglia in the superficial layers (Supplementary Fig. 7b) had few processes and extended their branches to the pial surface, similar to the macrophages. This indicates that the microglia had become active12, 19, 29. In addition, the density of microglia under the open-skull glass window (cortical layer I/II) was much higher than that under the control sides (1.62±0.25)24, 29. In addition, the GFAP immunostaining patterns in the surgery side are very strong and obviously different from those seen in the contralateral hemisphere (Supplementary Fig. 7c).

The above results show that the SOCW method does not induce obvious inflammatory responses in the brain cortex; hence, we can conclude that this SOCW technique is safe and reliable.

Monitoring the plasticity of dendritic protrusions based on the SOCW

We next applied this method to dynamically monitor the plasticity of dendritic protrusions in critical periods. To monitor spine turnover, we obtained high-resolution image stacks of the dendritic tuft. The dendritic branches were studded with numerous spines (56.6±1.4 spine per 100 μm), including mushroom-type, stubby and thin spines, as well as long filopodia-like protrusions. By time-lapse imaging dendritic protrusions over an hour (1 h), we found that they exhibited strong motility. Moreover, dendritic spines can suffer changes within 1 h, including appearance (Figure 6a) and disappearance (Figure 6b) of spines and changes of shape (Figure 6f), which points to changes in the wiring of neuronal circuits. We additionally studied the turnover of dendritic spines in the barrel cortex in vivo within 1 h after forming the SOCW. We found that spine formation and elimination were 3.20±0.21% and 1.83±0.52%, respectively (Figure 6c, 987 spines, n=6 mice). Compared with dendritic spines, filopodia exhibited higher motility. In addition, filopodia can even convert into spine-like protrusions (Figure 6e), demonstrating that filopodia are likely to be the precursors of dendritic spines46, 47. These results demonstrate the dynamic nature of these protrusions, which indicates that the plasticity of dendritic protrusions during the third week is very intense.

Dynamical monitoring of the plasticity of dendritic protrusions in infantile mice (P19) through the SOCW. Time-lapse images of dendritic branches over an hour (60 min). (a and b) Dendritic spines can a appear and b disappear within an hour. (c) Percentage of spines formed and eliminated within an hour, according to the SOCW technique (n=6 mice). (d and e) Filopodia can also d appear and e convert into a spine-like protrusion within an hour. (f) The morphology of dendritic spines can change within an hour. The triangle, arrow and asterisk show appearance, disappearance and morphological changes, respectively. Scale bar=25 μm (above) and 5 μm (below).

Monitoring dendrites and microglia after laser ablation under the SOCW

Laser-induced injury is a widely used injury model because the extent and site of the injury are easily controlled48, 49. We also applied this method to monitor dendrites and microglia after laser injury. We found that the dendrites on the laser injury side formed bead-like structures, while the sites that did not suffer damage remained in a normal state (Figure 7a and 7b). Microglia soma did not show any significant movement, but the processes with bulbous termini immediately moved toward the site of injury (Figure 7c and 7d). The SOCW technique enables us to characterize the effects of laser injury on cortical structures.

Changes induced by laser ablation in dendrites and microglia. (a) Morphology of dendrites after laser injury, obtained using the SOCW technique (P30, n=4 mice). After creating a localized ablation inside the cortex with a two-photon laser, nearby dendrites form bead-like structures. (b) Magnified images corresponding to the rectangle areas shown in a. (c) Morphology of microglia after laser injury, obtained using the SOCW method (P30, n=4 mice). After creating a localized injury, nearby microglial processes respond immediately with bulbous termini. (d) Magnified images corresponding to the rectangular areas shown in c. The arrows show the brain injury locations. Scale bar=25 μm.

Conclusions

In this study, we introduce an easy-handling, safe and effective SOCW for imaging cortical structures at synaptic resolution. Combined with two-photon microscopy, this SOCW technique allowed us to repeatedly visualize the neurons, microglia and microvasculature in the superficial cortical layers.

Compared with the current cranial windows, the SOCW has several advantages. First, the SOCW is easier to handle because the SOCW is established by topically applying reagents on the skull without much thinning or removing of the skull; thus, it may attract more researchers to opt for the SOCW technique. Second, this approach proved to be safe with little risk of producing inadvertent damage or inflammation. Because of its lack of brain inflammation, this technique is also more suitable for the study of the immune cells (microglia) that are highly sensitive to the microenvironment. However, there is a technical and practical limitation of the SOCW. The imaging depth is limited to the first 250 μm below the pial surface due to the existence of the skull, which is not comparable with traditional cranial windows. Therefore, the SOCW with no need for much thinning or removal of the skull, as an alternative technique, could permit us to image cortical cells and vasculature under extremely similar environments with the normal state of the brain.

References

Feng GP, Mellor RH, Bernstein M, Keller-Peck C, Nguyen QT et al. Imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron 2000; 28: 41–51.

Denk W, Strickler JH, Webb WW . Two-photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Science 1990; 248: 73–76.

Zipfel WR, Williams RM, Webb WW . Nonlinear magic: multiphoton microscopy in the biosciences. Nat Biotechnol 2003; 21: 1369–1377.

Svoboda K, Yasuda R . Principles of two-photon excitation microscopy and its applications to neuroscience. Neuron 2006; 50: 823–839.

So PT, Dong CY, Masters BR, Berland KM . Two-photon excitation fluorescence microscopy. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2000; 2: 399–429.

Helmchen F, Fee MS, Tank DW, Denk W . A miniature head-mounted two-photon microscope: high-resolution brain imaging in freely moving animals. Neuron 2001; 31: 903–912.

Perillo EP, Jarrett JW, Liu Y-L, Hassan A, Fernée DC et al. Two-color multiphoton in vivo imaging with a femtosecond diamond raman laser. Light Sci Appl 2017; e17095, doi:10.1038/lsa.2017.95.

Bar-Noam AS, Farah N, Shoham S . Correction-free remotely scanned two-photon in vivo mouse retinal imaging. Light Sci Appl 2016; 5: e16007; doi:10.1038/lsa.2016.7.

Helmchen F, Denk W . Deep tissue two-photon microscopy. Nat Methods 2005; 2: 932–940.

Kneipp M, Turner J, Estrada H, Rebling J, Shoham S et al. Effects of the murine skull in optoacoustic brain microscopy. J Biophotonics 2016; 9: 117–123.

Fan XF, Zheng WT, Singh DJ . Light scattering and surface plasmons on small spherical particles. Light Sci Appl 2014; 3: e179; doi:10.1038/lsa.2014.60.

Holtmaat A, Bonhoeffer T, Chow DK, Chuckowree J, De Paola V et al. Long-term, high-resolution imaging in the mouse neocortex through a chronic cranial window. Nat Protoc 2009; 4: 1128–1144.

Levasseur JE, Wei EP, Raper AJ, Kontos AA, Patterson JL . Detailed description of a cranial window technique for acute and chronic experiments. Stroke 1975; 6: 308–317.

Yang G, Pan F, Parkhurst CN, Grutzendler J, Gan WB . Thinned-skull cranial window technique for long-term imaging of the cortex in live mice. Nat Protoc 2010; 5: 201–208.

Yu XZ, Zuo Y . Two-photon in vivo imaging of dendritic spines in the mouse cortex using a thinned-skull preparation. J Vis Exp 2014; 87: e51520.

Takehara H, Nagaoka A, Noguchi J, Akagi T, Kasai H et al. Lab-on-a-brain: implantable micro-optical fluidic devices for neural cell analysis in vivo. Sci Rep 2014; 4: 6721.

Roome CJ, Kuhn B . Chronic cranial window with access port for repeated cellular manipulations, drug application, and electrophysiology. Front Cell Neurosci 2014; 8: 379.

Goldey GJ, Roumis DK, Glickfeld LL, Kerlin AM, Reid RC et al. Removable cranial windows for long-term imaging in awake mice. Nat Protoc 2014; 9: 2515–2538.

Drew PJ, Shih AY, Driscoll JD, Knutsen PM, Blinder P et al. Chronic optical access through a polished and reinforced thinned skull. Nat Methods 2010; 7: 981–984.

Dombeck D, Tank D . Two-photon imaging of neural activity in awake mobile mice. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2014; 2014: 726–736.

Nimmerjahn A . Optical window preparation for two-photon imaging of microglia in mice. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2012; 2012: 587–593.

Shih AY, Drew PJ, Kleinfeld D. Imaging vasodynamics in the awake mouse brain with two-photon microscopy. In: Zhao M, Ma H, Schwartz TH, editors. Neurovascular Coupling Methods. Neuromethods. New York: Humana Press; 2014. pp55–73.

Heo C, Park H, Kim YT, Baeg E, Kim YH et al. A soft, transparent, freely accessible cranial window for chronic imaging and electrophysiology. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 27818.

Dorand RD, Barkauskas DS, Evans TA, Petrosiute A, Huang AY . Comparison of intravital thinned skull and cranial window approaches to study CNS immunobiology in the mouse cortex. Intravital 2014; 3: e29728.

Portera-Cailliau C, Weimer RM, De Paola V, Caroni P, Svoboda K . Diverse modes of axon elaboration in the developing neocortex. PLoS Biol 2005; 3: e272.

Cruz-Martin A, Portera-Cailliau C . In vivo imaging of axonal and dendritic structures in neonatal mouse cortex. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2014; 2014: 57–64.

Kim TH, Zhang YP, Lecoq J, Jung JC, Li JE et al. Long-term optical access to an estimated one million neurons in the live mouse cortex. Cell Rep 2016; 17: 3385–3394.

Shih AY, Mateo C, Drew PJ, Tsai PS, Kleinfeld D . A polished and reinforced thinned-skull window for long-term imaging of the mouse brain. J Vis Exp 2012; 61: e3742.

Xu HT, Pan F, Yang G, Gan WB . Choice of cranial window type for in vivo imaging affects dendritic spine turnover in the cortex. Nat Neurosci 2007; 10: 549–551.

Zhu D, Larin KV, Luo QM, Tuchin VV . Recent progress in tissue optical clearing. Laser Photonics Rev 2013; 7: 732–757.

Wang J, Zhang Y, Li PC, Luo QM, Zhu D . Review: tissue optical clearing window for blood flow monitoring. IEEE J Sel Top Quant Electron 2014; 20: 6801112.

Chung K, Deisseroth K . CLARITY for mapping the nervous system. Nat Methods 2013; 10: 508–513.

Tainaka K, Kubota SI, Suyama TQ, Susaki EA, Perrin D et al. Whole-body imaging with single-cell resolution by tissue decolorization. Cell 2014; 159: 911–924.

Yang B, Treweek JB, Kulkarni RP, Deverman BE, Chen CK et al. Single-cell phenotyping within transparent intact tissue through whole-body clearing. Cell 2014; 158: 945–958.

Ertürk A, Becker K, Jährling N, Mauch CP, Hojer CD et al. Three-dimensional imaging of solvent-cleared organs using 3DISCO. Nat Protoc 2012; 7: 1983–1995.

Pan CC, Cai RY, Quacquarelli FP, Ghasemigharagoz A, Lourbopoulos A et al. Shrinkage-mediated imaging of entire organs and organisms using uDISCO. Nat Methods 2016; 13: 859–867.

Lee E, Choi J, Jo Y, Kim JY, Jang YJ et al. ACT-PRESTO: rapid and consistent tissue clearing and labeling method for 3-dimensional (3D) imaging. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 18631.

Renier N, Adams EL, Kirst C, Wu ZH, Azevedo R et al. Mapping of brain activity by automated volume analysis of immediate early genes. Cell 2016; 165: 1789–1802.

Berke IM, Miola JP, David MA, Smith MK, Price C . Seeing through musculoskeletal tissues: improving in situ imaging of bone and the lacunar canalicular system through optical clearing. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0150268.

Neu CP, Novak T, Gilliland KF, Marshall P, Calve S . Optical clearing in collagen- and proteoglycan-rich osteochondral tissues. Osteoarthr Cartil 2015; 23: 405–413.

Greenbaum A, Chan KY, Dobreva T, Brown D, Balani DH et al. Bone CLARITY: clearing, imaging, and computational analysis of osteoprogenitors within intact bone marrow. Sci Transl Med 2017; 9: eaah6518.

Wang J, Zhang Y, Xu TH, Luo QM, Zhu D . An innovative transparent cranial window based on skull optical clearing. Laser Phys Lett 2012; 9: 469–473.

Yang XQ, Zhang Y, Zhao K, Zhao YJ, Liu YY et al. Skull optical clearing solution for enhancing ultrasonic and photoacoustic imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imag 2016; 35: 1903–1906.

Kitaura H, Hishida R, Shibuki K . Transcranial imaging of somatotopic map plasticity after tail cut in mice. Brain Res 2010; 1319: 54–59.

Pekny M, Nilsson M . Astrocyte activation and reactive gliosis. Glia 2005; 50: 427–434.

Zuo Y, Lin A, Chang P, Gan WB . Development of long-term dendritic spine stability in diverse regions of cerebral cortex. Neuron 2005; 46: 181–189.

Holtmaat AJGD, Trachtenberg JT, Wilbrecht L, Shepherd GM, Zhang XQ et al. Transient and persistent dendritic spines in the neocortex in vivo. Neuron 2005; 45: 279–291.

Davalos D, Grutzendler J, Yang G, Kim JV, Zuo Y et al. ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat Neurosci 2005; 8: 752–758.

Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Helmchen F . Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science 2005; 308: 1314–1318.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants Nos. 91232710, 31571002), the Science Fund for Creative Research Groups (Grant No. 61721092) and the Director Fund of WNLO. We are thankful to ZH Zhang for providing the Cx3cr1EGFP/+ mice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Note: Supplementary Information for this article can be found on the Light: Science & Applications website.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, YJ., Yu, TT., Zhang, C. et al. Skull optical clearing window for in vivo imaging of the mouse cortex at synaptic resolution. Light Sci Appl 7, 17153 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2017.153

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2017.153

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Large-scale cranial window for in vivo mouse brain imaging utilizing fluoropolymer nanosheet and light-curable resin

Communications Biology (2024)

-

Optogenetic stimulation of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons prevents neuroinflammation and neuropsychiatric manifestations in pristane induced lupus mice

Behavioral and Brain Functions (2023)

-

Near-infrared luminescence high-contrast in vivo biomedical imaging

Nature Reviews Bioengineering (2023)

-

Minimally invasive longitudinal intravital imaging of cellular dynamics in intact long bone

Nature Protocols (2023)

-

Multifocal fluorescence video-rate imaging of centimetre-wide arbitrarily shaped brain surfaces at micrometric resolution

Nature Biomedical Engineering (2023)